Abstract

Nodal Malignant Lymphoma (with Comments on Extranodal Malignant Lymphoma and Metastatic Cancer): this chapter outlines the incidence, risk factors, clinical presentation, investigations, treatments and prognosis of cancer at this anatomical site. These features are correlated with the core data that are required to make the corresponding histopathology reports of a consistently high quality, available in an appropriate timeframe, and clinically relevant to patient management and prognosis. Summary details of the common cancers given at this site include: gross description, histological types, tumour grade/differentiation, extent of local tumour spread, lymphovascular invasion, lymph node involvement, and the status of excision margins. Current WHO Classifications of Malignant Tumours and TNM7 are referenced. Notes are provided on other associated pathology, contemporary use of immunohistochemistry, updates on the role of evolving molecular tests, and the use of these ancillary techniques as biomarkers in diagnosis, and prediction of prognosis and treatment response. A summary is given of the commoner non-carcinoma malignancies that are encountered at this site in diagnostic practice.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Representing 5–7 % of all cancers and 55 % of haematological malignancies with an increasing incidence, malignant lymphoma presents as persistent, mobile, rubbery and non-tender lymphadenopathy with or without associated systemic symptoms such as weight loss, itch or night sweats. Investigation is by full blood picture (infections/leukaemias), serology (infections/autoimmune diseases), fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC: to exclude metastatic cancer) and biopsy. Clinical staging is by CT/PET/MRI scans appropriate to the clinical context, bone marrow aspirate and trephine biopsy.

In the UK contemporary guidance from the Royal College of Pathologists and the NHS National Cancer Action Team indicates concordance of diagnosis for malignant lymphomas of less than 85 %. It is advised that diagnosis should be the remit of a specialist integrated haematological malignancy diagnostic service covering a catchment population of at least two million. There should be a single integrated report encompassing the requisite specialist morphological expertise, immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, cytogenetics, in situ hybridization and molecular diagnostics. Local arrangements will require at least prompt referral through the cancer network to the appropriate haematological malignancy diagnostic team. Underpinning this will be the ongoing need for general diagnostic pathologists to competently recognize the wide range of haematolymphoid pathology so that relevant and expeditious clinicopathological referrals are made.

1 Gross Description and Morphological Recognition

1.1 Specimen

-

FNAC/needle biopsy core/excisional biopsy/regional lymphadenectomy.

Regional lymphadenectomy comprises part of a formal cancer resection operation. This can either be for removal of a primary malignant lymphoma e.g. gastrectomy, or, where malignant lymphoma is found incidentally in a resection for a primary carcinoma e.g. in the mesorectal nodes of an anterior resection for rectal cancer.

-

Size (cm) and weight (g)

-

Colour, consistency, necrosis.

The preferred specimen for diagnosis, subtyping and grading of nodal malignant lymphoma is an excisional lymph node biopsy carefully taken by an experienced surgeon to ensure representation of disease and avoidance of traumatic artifact. Submission of the specimen fresh to the laboratory allows material to be collected for flow cytometry, or imprints to be made, to which a wide panel of immunohistochemical antibodies can be applied some of which are more effective than on formalin fixed paraffin processed tissue sections e.g. the demonstration of light chain restriction. Tissue can also be harvested for molecular and genetic techniques. Morphological classification is generally based on well fixed, thin slices, processed through to paraffin with high quality 4 μm H&E sections. Core biopsy may be the only option if the patient is unwell or the lesion is relatively inaccessible e.g. mediastinal or para-aortic lymphadenopathy. Allowances must be made in interpretation for underestimation of nuclear size, sampling error and artifact. Confirmation of lymphomatous (or other) malignancy is the prime objective and further comments on subtyping and grading given with care and only if definitely demonstrable. Despite these considerations a positive diagnosis can be given in a significant percentage of cases. Importantly, interpretation should be in light of the clinical context i.e. the presence of palpable or radiologically proven significant regional or systemic lymphadenopathy, and the absence of any obvious carcinoma primary site. Tumour heterogeneity must also be borne in mind. The same principles apply to FNAC, which is excellent at excluding inflammatory lymphadenopathy e.g. abscess or sarcoidosis, and non-lymphomatous cancer (e.g. metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, breast carcinoma or malignant melanoma). It is also reasonably robust at designating Hodgkin’s and high-grade non-Hodgkin’s malignant lymphoma. Morphology is the principal diagnostic criterion when assessing excisional lymph node biopsies, core biopsies and FNAC but is supplemented by immunohistochemical antibody panels targeted at the various diagnostic options e.g. a small lymphoid cell proliferation (lymphocytic lymphoma versus mantle cell lymphoma etc). In addition, flow cytometry and molecular gene rearrangements can be important in determining a diagnosis and its attendant treatment and prognosis. Limited needle sampling techniques can also be used in patients with a previous biopsy proven tissue diagnosis of malignant lymphoma and in whom recurrence is suspected. However, possible transformation of grade must be considered and even change of malignant lymphoma type e.g. small lymphocytic lymphoma to Hodgkin’s malignant lymphoma, or Richter‘s transformation to diffuse large B cell malignant lymphoma. A range of inflammatory and neoplastic lymph node pathology may also be encountered secondary to chemotherapy and immunosuppression e.g. tuberculosis, EBV (Epstein Barr Virus) driven lymphoproliferation, and various malignant lymphomas.

A systematic approach to excisional lymph node biopsies will allow the majority to be categorised as specific inflammatory pathology, benign or malignant, and the latter as haematolymphoid or non-haematolymphoid in character. Diagnostic morphological clues to malignant lymphoma are architectural and cytological.

Architectural descriptors are: diffuse, follicular, nodular, marginal zone, sinusoidal, paracortical, and angiocentric distributions.

Cytological descriptors are: cell size (small, medium (the size of a histiocyte nucleus), large), the relative proportions of the cell populations, specific cytomorphological features, and cellular proliferative activity (mitoses, apoptosis, Ki-67 index). Various malignant lymphomas are also characterized by a typical host connective tissue and/or cellular inflammatory response.

Low Power Magnification

-

Capsular/extracapsular spillage of lymphoid tissue

-

Capsular thickening and banded septal fibrosis or hyaline sclerosis

-

Loss of sinusoids with either compression or filling due to a cellular infiltrate

-

Alteration in follicular architecture with changes in

-

(a)

Distribution: proliferation in the medulla

-

(b)

Size and shape: relative uniformity of appearance

-

(c)

Definition: loss of the mantle zone- germinal centre interface/“filling up” of the germinal centre/loss of tingible body macrophages

-

(d)

Absence: the architecture may be completely effaced by a diffuse infiltrate

-

(a)

-

Prominent post capillary venules.

High Power Magnification

-

Presence of a background polymorphous inflammatory cellular infiltrate e.g. eosinophils, plasma cells and histiocytes (epithelioid in character ± granulomas)

-

Alterations in the proportions of the normal cellular constituents

-

Dominance of any mono- or dual cell populations

-

Presence of atypical lymphoid cells

-

(a)

Nuclei: enlargement/irregularity/hyperchromasia/bi- or polylobation/mummification/apoptosis

-

(b)

Nucleoli: single/multiple/central/peripheral/eosinophilic/basophilic/Dutcher inclusions

-

(c)

Cytoplasm: clear/vacuolar/eosinophilic/scant/plentiful/paranuclear hof.

-

(a)

A morphological diagnostic short list should be created e.g. mixed cellularity Hodgkin’s lymphoma versus T cell malignant lymphoma versus T cell rich large B cell malignant lymphoma, and a targeted immunohistochemical antibody panel used. The determination of cell lineage is a prerequisite for diagnosis. In the majority of cases immunohistochemistry will confirm the preliminary diagnosis, but will in a minority lead to its modification and either a refinement within or revision of diagnostic category. A pitfall for the unwary is aberrant expression of T cell antigens by a B cell malignant lymphoma and vice versa e.g. expression of CD5 in chronic lymphocytic lymphoma/leukaemia. Clonality and gene rearrangement studies, either by immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry or molecular techniques can be important in confirming the neoplastic character of the B and T cell populations. Another relevant ancillary technique in various clinical settings is in situ hybridization for EBERs (Epstein Barr Encoded RNAs). Patient age, disease site and distribution also contribute to making a correct diagnosis e.g. nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin’s malignant lymphoma usually presents in younger patients and as solitary or localized lymphadenopathy rather than extensive disease.

2 Histological Type and Differentiation/Grade

Therapeutic and prognostic distinction is made between Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s malignant lymphomas (HL/NHLs), with a significant proportion of the former being reclassified as variants of the latter on the basis of improved immunophenotyping. Within classical Hodgkin’s malignant lymphoma there is a differentiation spectrum from nodular sclerosis and lymphocyte rich through mixed cellularity to lymphocyte depleted, with nodular sclerosis divided into two subtypes that are of prognostic significance in limited stage disease. In non-Hodgkin’s malignant lymphoma better differentiated tumours are of a follicular pattern and small cell type, and less differentiated lesions diffuse and large cell in character. This differentiation spectrum can predict the likelihood of untreated disease progression from indolence to aggressive behaviour, but paradoxically often does not correlate with extent of disease stage, chemoresponsiveness, long term disease free survival and potential for cure. For example, grade 1/2 follicular lymphoma is often of extensive distribution (stage IV), indolent in behaviour, yet incurable and ultimately fatal at 5–10 years after diagnosis. Thus, morphology with corroborative immunophenotyping (e.g. a Ki-67 proliferation index >90 %) can identify those high-grade diagnoses requiring curative intent high dose multi-agent chemotherapy e.g. Burkitt’s malignant lymphoma, mediastinal large B cell malignant lymphoma, lymphoblastic lymphoma. As can be seen size matters in grading, but not always as cell maturation (Burkitt’s, lymphoblastic lymphoma) and aggressive behaviour linked to specific underlying chromosomal alterations (e.g. mantle cell lymphoma) must be taken into account. Thus the prognostic information used to determine treatment of malignant lymphoma is provided by the histological subtyping and grading, supported by immunohistochemistry the diagnostic importance of which varies with the malignant lymphoma subtype e.g. a significant contributor to diagnoses such as T cell malignant lymphoma and anaplastic large cell malignant lymphoma. Compatible molecular analysis is also of importance in defining these characteristic malignant lymphoma types, treatment response and behaviour.

2.1 Non-Hodgkin’s Malignant Lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin’s malignant lymphoma (NHL) is classified according to the WHO system (Table 35.1) which defines each disease by its morphology, immunophenotype, genetic characteristics, proposed normal counterpart and clinical features. It is reproducible, with prognostic and therapeutic implications. Broad categories are malignant lymphomas of B, T or NK (natural killer) cell types. Malignant lymphomas and leukaemias are both included as many haematolymphoid neoplasms have both solid and fluid circulatory phases. Prognosis relates to stage of disease, treatment protocols and individual disease biology.

2.2 Hodgkin’s Malignant Lymphoma

2.2.1 WHO Classification

Comprising nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin’s malignant lymphoma (NLPHL – a B cell malignant lymphoma), and classic Hodgkin’s malignant lymphomas encompassing nodular sclerosis, lymphocytic rich, mixed cellularity and lymphocyte depleted variants. Hodgkin’s malignant lymphoma is a tumour of abnormal B lymphocyte cell lineage.

2.2.2 Lymphocyte and Histiocyte (L and H) Predominant: Multilobated “Popcorn” Cell

-

Nodular: a B cell lymphoma of early stage (cervical, axilla, groin) in young men and low-grade indolent behaviour (80 % 10 year survival) with a 4 % risk of diffuse large B cell change. Some arise from progressive transformation of germinal centres.

-

Diffuse: a controversial category with overlap between lymphocyte rich classic Hodgkin’s malignant lymphoma, vaguely nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin’s, and exclusion of other entities such as T cell/histiocyte rich large B cell NHL.

Classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma includes nodular sclerosis, lymphocyte rich classical, mixed cellularity and lymphocyte depleted categories. They vary in their clinical features, growth pattern, degree of fibrosis, background cells, tumour cell numbers and atypia, and, frequency of EBV infection.

2.2.3 Nodular Sclerosis: Lacunar Cell

-

Female adolescents, young adults. Mediastinal or cervical involvement and either localised disease or high stage at presentation. Moderately aggressive but curable.

-

Birefringent fibrous bands (capsular and intranodal septa) with mixed inflammatory cell nodules containing lacunar cells, or, cellular phase (rich in lacunar cells, scant fibrosis)

-

Type 1.Footnote 1

-

Type 2:Footnote 2 lymphocyte depletion or pleomorphism of R-S (Reed Sternberg) cells in more than 25 % of nodules. An alternative descriptor is syncytial variant (sheets/clusters of R-S cells with central necrosis and a polymorph infiltrate).

2.2.4 Mixed Cellularity: Reed Sternberg Cell

-

Male adults, high stage disease at presentation: lymph nodes, spleen, liver ± bone marrow. Moderately aggressive but curable.

-

R-S cells of classic type in a mixed inflammatory background. A category of exclusion in that no specific features of other subtypes are present.

2.2.5 Lymphocyte Rich Classic

-

Scattered R-S cells against a nodular or diffuse background of small lymphocytes but no polymorphs.

2.2.6 Lymphocyte Depleted

-

Older patients, high stage disease at presentation, aggressive, association with HIV.

-

R-S cells ± pleomorphism; diffuse fibrosis (fibroblasts obscure scattered R-S cells) and reticular variants (cellular, pleomorphic R-S cells).

2.2.7 Other Features

-

Follicular and interfollicular Hodgkin’s, Hodgkin’s with a high epithelioid cell content (granulomas).

-

R-S cells: classic mirror image, binucleated cell with prominent eosinophilic nucleolus (“owl’s eye” appearance) characteristic of the mixed cellularity and lymphocyte depleted categories. Mononuclear, polylobated and necrobiotic (mummified) forms are also common. Lacunar cells (nodular sclerosis) can be mono-, bi- or polylobated (± necrobiotic), with characteristic perinuclear artifactual cytoplasmic retraction and clarity. Mononuclear cells tend to be termed Hodgkin’s cells. Hodgkin/R-S cells are derived from germinal centre B cells with monoclonal, non-functional immunoglobulin gene rearrangements.

2.2.8 Immunophenotype

Lymphocyte Predominant Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

-

Popcorn cells: CD45/CD20/CD79a/EMA/J chain/bcl-6 positive, CD30 weak or negative, CD15 negative, EBV negative. Nuclear transcription factors Oct2/BoB1 positive.

-

Small lymphocytes: nodules of B cells (CD20) and intervening T cells (CD3).

-

Rosettes: CD57/CD4 positive T cell rosettes around the popcorn cells.

Classic Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

-

R-S cells: CD15/CD30 in 75 %/90 % of cases respectively, EBV (60–70 % of cases), CD20/79a±, CD45/ALK negative. MUM1/PAX5 positive. CD15 positivity can be weak and focal limited to the Golgi apparatus in 15 % of cases.

-

Small lymphocytes: T cells (CD3/CD4).

In Hodgkin’s lymphoma the heterogeneous cellular background (comprising 90 % of the tissue) is an important part of the diagnosis: small lymphocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils, fibroblasts, histiocytes and follicular dendritic cells. Note that this cytokinetic diathesis is also seen in T cell NHLs and T cell rich B cell NHLs. Another differential diagnosis with which there can be overlap is anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Other features are progressive transformation of germinal centres (particularly associated with NLPHL), granulomas, necrosis, interfollicular plasma cells and reactive follicular hyperplasia, all of which should prompt a careful search for R-S cells.

2.3 Differential Diagnoses in Haematolymphoid Pathology

Relatively common diagnostic difficulties in lymph node assessment are:

-

Follicular hyperplasia vs. follicular lymphoma

-

Follicular hyperplasia vs. partial nodal involvement by in situ follicular lymphoma

-

Progressive transformation of germinal centres vs. NLPHL

-

T cell hyperplasia vs. dermatopathic lymphadenopathy vs. T cell lymphoma

-

Underestimation of grade in small lymphocytic infiltrates e.g. mantle cell or lymphoblastic lymphomas

-

Burkitt’s lymphoma vs. Burkitt’s like diffuse large B cell lymphoma

-

Hodgkin’s lymphoma vs. anaplastic large cell lymphoma, and subtle infiltration of sinusoids by the latter

-

Interfollicular Hodgkin’s lymphoma

-

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma vs. metastatic carcinoma, malignant melanoma or germ cell tumour

-

Post immunosuppression lymphoproliferative disorders.

Important non-malignant differential diagnoses for malignant lymphoma are Castleman’s disease (hyaline vascular and plasma cell variants), drug induced (e.g. phenytoin) and viral reactive hyperplasia with paracortical transformation (e.g. herpesvirus, infectious mononucleosis), and necrotising and granulomatous lymphadenitis (Kikuchi’s, toxoplasmosis, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis). A clinical history of immunosuppression and subsequent EBV driven lymphoproliferation must always be borne in mind.

3 Extent of Local Tumour Spread

Part of node or whole node.

Extracapsular into adjacent soft tissues or organ parenchyma.

A TNM classification is not used as the primary site of origin is often uncertain and attribution of N and M stages would therefore be arbitrary.

3.1 Stage: Ann Arbor Classification

I | Single lymph node region or localised extralymphatic site/organ |

II | Two or more lymph node regions on same side of the diaphragm or single localised extralymphatic site/organ and its regional lymph nodes ± other lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm |

III | Lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm ± a localised extralymphatic site/organ or spleen |

IV | Disseminated (multifocal) involvement of one or more extralymphatic organs ± regional lymph node involvement, or single extralymphatic organ and non-regional nodes. Includes any involvement of liver, bone marrow, lungs or cerebrospinal fluid |

(a) Without weight loss/fever/sweats | |

(b) With weight loss/fever/sweats: | |

Fever >38 °C | |

Night sweats | |

Weight loss >10 % of body weight within the previous 6 months. | |

Subscripts e.g. | IIIE denotes stage III with Extranodal disease |

IIIS denotes stage III with splenic involvement | |

III3 denotes stage III with involvement of 3 lymph node regions: >2 is prognostically adverse. | |

Lymph node regions | Head, neck, face |

Intrathoracic | |

Intraabdominal | |

Axilla/arm | |

Groin/leg | |

Pelvis. |

Other major structures of the lymphatic system are the spleen, thymus, Waldeyer’s ring (palatine, lingual and pharyngeal tonsils), vermiform appendix and ileal Peyer’s patches. Minor sites include bone marrow, liver, skin, lung, pleura and gonads.

Bilateral involvement of axilla/arm or inguinal/leg regions is considered as involvement of two separate regions.

Direct spread of lymphoma into adjacent tissues or organs does not alter the classification e.g. gastric lymphoma into pancreas and with involved perigastric lymph nodes is stage IIE.

Involvement of two or more discontinuous segments of gastrointestinal tract is multifocal and classified as stage IV e.g. stomach and ileum. However multifocal involvement of a single extralymphatic organ is IE.

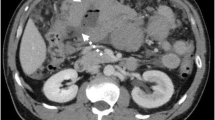

Involvement of both organs of a paired site e.g. lungs is also IE. Regional nodes for an extranodal lymphoma are those relevant to that particular site e.g. gastric lymphoma – perigastric, left gastric, common hepatic, splenic and coeliac nodes (Figs. 35.1, 35.2, 35.3, 35.4 and 35.5)

Malignant lymphoma (Reproduced, with permission, from Wittekind et al. (2005), © 2005)

Malignant lymphoma (Reproduced, with permission, from Wittekind et al. (2005), © 2005)

Malignant lymphoma (Reproduced, with permission, from Wittekind et al. (2005), © 2005)

Malignant lymphoma (Reproduced, with permission, from Wittekind et al. (2005), © 2005)

Malignant lymphoma (Reproduced, with permission, from Wittekind et al. (2005), © 2005)

Once the primary tissue diagnosis has been made staging laparotomy has been replaced by assessment of clinical and radiological parameters e.g. peripheral blood differential cell counts, abnormal liver function tests, and imaging for hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. Bone marrow biopsy remains part of normal staging which is otherwise mostly clinical. Bone marrow or nodal granulomas per se are not sufficient for a positive diagnosis of involvement and diagnostic Hodgkin’s cells are needed. Bone marrow involvement by NHL can be diffuse, nodular or focal, and paratrabecular infiltration is a characteristic site of distribution.

4 Lymphovascular Invasion

Present/absent.

Intra-/extratumoural.

Vessel wall invasion and destructive angiocentricity can be a useful indicator of malignancy in NHL and in specific subtypes e.g. nasal angiocentric T/NK cell lymphoma.

5 Immunophenotype

In general an antibody panel is used with both expected positive and negative antibodies, and, two antibodies per lineage. Select combinations are targeted at determining the nature of the various lymphoid proliferations e.g. follicular (follicular lymphoma vs reactive hyperplasia), small cell (CLL/SLL vs. mantle cell lymphoma), and large cell (HL vs. NHL vs. ALCL). Interpretation must take into account artifacts such as poor fixation or lymph node necrosis following FNAC. In the latter expression of nuclear antigens is affected first and T cell stains can give false positive results in inflammatory debris. Some antigens such as CD20 retain remarkably robust expression. Expression must also be appropriate to the antibody concerned e.g. localization to the nucleus, cytoplasm or cell membrane. Suitable in built positive, and, external positive and negative controls are used. Interpretation must also account for expression in physiological cell populations in the test tissue. Commonly used antibodies available for formalin fixed, paraffin embedded sections are

CD45 | Pan lymphoid marker (Leucocyte Common Antigen) and excellent in the characterisation of a poorly differentiated malignant tumour e.g. malignant lymphoma vs. carcinoma vs. malignant melanoma. |

CD20 | Mature B cell marker (and some cases of plasma cell myeloma). Lymphoma cell positivity is a marker for specific rituximab monoclonal antibody therapy. |

CD79a | As for CD20 but also less mature (pre B: lymphoblastic) cells and plasma cell tumours. |

CD3 | Pan T cell marker. |

CD5 | T cell marker and aberrant expression in some variants of B cell lymphoma (lymphocytic, mantle cell and splenic marginal zone lymphomas). |

CD4, CD8 | T cell subsets of use in some T cell proliferations e.g. mycosis fungoides. CD7, AML and granzyme C may also be useful in extranodal cases. Other T cell markers include CD45R0 (UCHL1), CD43 (MT1) and TIA-1. |

CD10 | Lymphoblastic lymphoma (CALLA), Burkitt’s lymphoma and follicle centre lymphoma. Also with CD5 and CD23 in the differential diagnosis of small B cell lymphomas (lymphocytic CD5/CD23+: mantle cell CD5+: follicle centre cell CD10+). Forty percent of DLBCL are CD10 positive. |

CD15, CD30 | Classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma R-S cells. CD30 is also positive in ALCL, a proportion of DLBCLs, embryonal carcinoma and malignant melanoma. CD15 is positive in some large T cell lymphomas. |

CD56, CD57 | Natural killer (NK) cells e.g. angiocentric sinonasal lymphoma. Also T cells and plasma cell myeloma/AML (CD56). |

CD68 | Macrophages, cells of granulocytic lineage. |

CD 38/138 | Plasma cells and multiple myeloma (usually CD45/20 negative; CD79a±). Other low grade B cell lymphomas (CD38+ CLL has a worse prognosis). |

CD123 | Hairy cell leukaemia, AML. |

κ, λ light chains | Immunoglobulin light chain restriction is difficult to demonstrate satisfactorily in paraffin sections but more easily shown on fresh imprint preparations or by in situ hybridisation. |

CD21, CD23 | Follicular dendritic cells. CD23 also stains most B cell lymphocytic lymphomas, some follicular and DLBCLs. |

bcl-1/cyclin D1 | Mantle cell lymphoma with the t(11:14) translocation. A nuclear epitope. Also some hairy cell leukaemia and plasma cell myeloma cases. p27kip1 is positive in cyclin D1 negative mantle cell lymphoma. |

bcl-2 | An apoptosis regulator: many B cell lymphomas including follicular t(14:18) and others. Also normal B, T cells and negative in reactive germinal centres. Strong expression is adverse in DLBCLs. |

bcl-6 | Follicle centre lymphoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma and a large proportion of DLBCLs. A transcription factor in the nuclei of germinal centre cells. |

Ki-67/MIB-1 | Nuclear proliferation marker useful for identifying high-grade lymphomas e.g. Burkitt’s (98–100 %), lymphoblastic lymphoma (also tdt positive), and DLBCL with a high proliferation fraction. Its distribution in the follicle centre is helpful in distinguishing reactive lymphoid hyperplasia from low-grade lymphoma. |

EBV | LMP-1 (latent membrane protein) antibody is positive in a proportion of R-S cells in HL. In situ hybridisation is more sensitive with a higher rate (60–70 %) of positivity. |

Tdt | Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase is positive in precursor B and T cell lymphoblastic lymphomas. A nuclear epitope. |

CD1a | Langerhans cell histiocytosis, cortical thymic T cells. |

ALK-1/(CD246) | Nucleophosmin-anaplastic lymphoma kinase fusion protein associated with the ALK-1 gene t(2:5) translocation and good prognosis ALCLs. |

MYC | Identifies an aggressive subset of DLBCLs that are less responsive to usual chemotherapy agents. |

MUM1 | A nuclear proliferation/differentiation epitope positive in post germinal centre B cells. It is of prognostic value in DLBCLs and stains classic R-S cells. |

PAX5 | A nuclear gene expression/differentiation transcription factor in B lymphoctyes and R-S cells. |

Oct2/BoB1 | B cell transcription factors positive in the nuclei of NLPHL L and H popcorn cells. Also in DLBCL. |

EMA | Plasma cells, ALCL, NLPHL L and H cells. |

Lysozyme | (muramidase/myeloperoxidase) – granulocytic and myeloid cell lineages. |

AML | Also CD34, CD43, CD68, CD117, neutrophil elastase and chloroacetate esterase. |

p53 | A prognostic marker in various lymphoid neoplasms. |

p21 | A prognostic marker in multiple myeloma. |

S100 | Interdigitating reticulum cells, Langerhans cells. |

Factor VIII/CD61 | Markers of megakaryocytes. |

5.1 Molecular Techniques

Immunoglobulin clonal heavy and light chain restriction and T cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangements using polymerase chain reaction are of use in difficult diagnostic cases e.g. follicular hyperplasia vs. follicular lymphoma, or T zone reactive hyperplasia vs. malignant lymphoma. Also, where immunohistochemistry has been equivocal (e.g. dubious cyclin D1 staining in mantle cell lymphoma) chromosomal studies for specific translocations have a role to play. These techniques vary in their applicability to fresh tissue and routine paraffin sections and suitable arrangements for prompt tissue transportation and referral on a regional network basis should be put in place. A majority of malignant lymphomas can be provisionally diagnosed without these techniques but their role is rapidly evolving in importance with respect to diagnostic confirmation, prognostication and therapy.

The evolution of new generation robust antibodies applicable to paraffin sections with unmasking of antigenic sites by antigen retrieval methods and more sensitive visualization techniques has led to considerable reclassification of malignant lymphomas and emergence of new entities. For example lymphocyte depleted and mixed cellularity Hodgkin’s lymphoma are diminishing as the full spectrum of NHL widens viz. T cell NHL, anaplastic large cell NHL, T cell rich B cell lymphoma (<10 % CD20 positive large cells on a background of CD3 small lymphocytes). Unusually composite (HL/NHL) and borderline (HL/ALCL) cases also occur. It is important that a panel of antibodies is used and markers assessed in combination. An example of this is in the sometimes difficult differential diagnosis of florid reactive hyperplasia versus follicular lymphoma. Benign follicle centres are bcl-2 negative, contain CD 68 positive macrophages, and show strong polar zonation of Ki-67 positivity. Conversely malignant follicles are diffusely bcl-2 positive with a low and evenly distributed Ki-67 proliferation index (unless predominantly centroblastic) and an absence of CD 68 positive macrophages. Thus morphology and immunohistochemistry are used in tandem supplemented by molecular immunoglobulin and gene rearrangement studies. It should also be noted that clonality does not always correlate with progression to malignant lymphoma as has been demonstrated in some inflammatory skin, salivary and gastric biopsies.

Formalin fixation and high quality, thin (4 μm) paraffin sections are adequate for morphological characterisation in most cases. Fixation should be sufficient (24–36 h) but not excessive as this may mask antigenic sites.

Progressive transformation of germinal centres will sometimes subsequently develop nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin’s disease characterised by the emergence of diagnostic popcorn or R-S cells.

The majority (60–70 %) of NHLs are diffuse large B cell lymphomas and follicular lymphoma.

6 Characteristic Lymphomas

6.1 Precursor B Cell Lymphoblastic Lymphoma/Leukaemia

-

Presents as childhood leukaemia or occasionally solid tumour (skin, bone, lymph node) and relapses in the central nervous system or testis.

-

75 % survival in childhood but <50 % in adults. Aggressive but potentially curable by multiagent chemotherapy.

-

Medium sized round lymphoid cells with small nucleolus, mitoses.

-

CD79a, CD10, tdt, CD99±, Ki-67 >95 %, CD20±.

6.2 B Cell Lymphocytic Lymphoma/Chronic Lymphoctic Leukaemia (CLL)

-

5–10 % of lymphomas occurring in older adults with diffuse lymph node, bone marrow and blood involvement, and hepatosplenomegaly.

-

Indolent and incurable with 5–10 year survival even without treatment but ultimately fatal.

-

Small lymphocytes with pale proliferation centres (immunoblasts/prolymphocytes)

-

CD45, CD20, CD5, CD23, bcl-2, Ki-67 <20 %. Cyclin D1 and CD10 negative.

-

Richter’s transformation to large cell lymphoma in 3–5 % of cases. Worse prognosis cases are CD38 positive.

-

Occasional cases have Hodgkin’s like cells (CD30/15) and <1 % develop classic HL.

6.3 Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma

-

1–2 % of cases and in the elderly involving bone marrow, nodes and spleen. Indolent course with a median survival of 5–10 years.

-

Monoclonal IgM serum paraprotein with hyperviscosity symptoms and autoimmune/cryoglobulin phenomena.

-

Small lymphocytes, plasmacytoid and plasma cells.

-

Intranuclear Dutcher and cytoplasmic Russell bodies.

-

CD45, CD20, VS38 positive and CD5/CD10/CD23 negative.

6.4 Marginal Zone Lymphoma of MALT (Mucosa Associated Lymphoid Tissue)

-

8 % of NHLs, stomach 50 % of cases, also salivary gland, lung, thyroid, orbit and skin. Multiple extranodal sites in 25–45 % of cases. Eighty percent are stage I or II disease and indolent. Many are cured by local excision, or antibiotic therapy in gastric MALToma.

-

Usually extranodal associated with chronic autoimmune or antigenic stimulation.

-

Centrocyte like cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells (scattered immunoblast and centroblast like cells).

-

Destructive lymphoepithelial lesions, reactive germinal centres and follicular colonisation by the lymphoma cells.

-

CD45, CD20 positive but CD5/10/23 negative.

-

Lymph node variant is monocytoid B cell lymphoma: indolent (60–80 % 5 year survival) but has potential for large cell transformation.

-

Gastric MALT with t(11:18) confers resistance to anti-helicobacter treatment.

-

Splenic marginal zone lymphoma: splenomegaly, lymphocytosis, stage III/IV disease.

6.5 Hairy Cell Leukaemia

-

Rare, elderly in the bone marrow, spleen and lymph nodes. Typically marked splenomegaly with pancytopaenia. Ten year survival >90 %.

-

“Fried egg” perinuclear cytoplasmic clarity with prominent cell boundaries.

-

CD45, CD20, CD72(DBA44), CD123, tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) positive, cyclin D1 ± .

6.6 Mantle Cell Lymphoma

-

6 % of NHLs predominantly in older adult males (75 %).

-

Extensive disease including spleen, bone marrow, Waldeyer’s ring ± bowel involvement (multiple lymphomatous polyposis).

-

Monomorphic small to medium sized irregular nuclei (centrocytic). Rare blastoid and pleomorphic variants.

-

Diffuse with vague architectural nodularity.

-

CD45, CD20, and typically CD5/cyclin D1 (t 11:14) /CD43 positive.

-

CD10, CD23, bcl-6 negative. Cyclin D1 negative cases can be p27kip1 positive.

-

Aggressive with mean survival of 3–5 years. A high Ki-67 index (>40–60 %) is prognostically adverse.

6.7 Follicular (Follicle Centre) Lymphoma

-

30 % of adult NHLs and transformation to DLBCL is relatively common.

-

Patterns: follicular, follicular and diffuse, diffuse (see Table 35.1)

-

Cell types: centroblasts with large open nuclei, multiple small peripheral basophilic nucleoli and variable cytoplasm.

-

Centrocytes with medium sized irregular nuclei.

-

-

Grade: 1/2/3 according to the number of centroblasts per high power field (see Table 35.1). Grade 3 has a high Ki-67 and 50 % may be bcl-2 negative – it is high-grade requiring R-CHOP chemotherapy and is to be distinguished from low-grade (grade 1/2) disease.

-

CD45, CD20, CD10 (60 %), bcl-2 (t 14:18; 70–95 %), bcl-6.

-

Usually CD21/23 positive and CD5 negative (20 % positive).

-

High stage disease at presentation (splenomegaly and bone marrow involvement in 40 % of cases), and indolent time course, but late relapse (5–10 years) with large cell transformation in 25–35 % of cases to DLBCL.

-

Pattern and grade can vary within a lymph node necessitating adequate sampling.

6.8 Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

-

30 % of adult NHLs, 40 % are extranodal (especially stomach, skin, central nervous system, bone, testis etc). Forms a rapidly growing mass in older patients which usually arises de-novo, or, occasionally from low-grade B cell NHL. Aggressive but potentially curable – rituximab therapy has improved outlook considerably.

-

Centroblasts, immunoblasts (prominent central nucleolus), bi-/polylobated, cleaved, anaplastic large cell (ALK+), plasmablastic (HIV+) forms, basophilic cytoplasm.

-

Aggressive variants: T cell/histocyte rich, mediastinal/thymic, intravascular, primary effusion (chronic inflammation associated), primary central nervous system.

-

CD45, CD20, CD79a, Ki-67 40–90 %, CD10 (30–60 %), bcl-2 (30 %), bcl-6 (60–90 %), CD5/23/CD30/CD43±. MUM1(35–65 %).

-

Strong bcl-2 expression is adverse.

-

Hans clinical algorithm: DLBCLs of germinal centre origin (CD10+, or, CD10-/bcl-6 +/MUM1−) are of better prognosis (76 % 5 year survival) than those of non-germinal centre origin (CD10-/bcl-6− or, CD10-/bcl-6+/MUM1+: 34 % 5 year survival). “Germinal centre markers” include CD10, bcl-6, CD21 and CD23 while MUM-1 (Interferon Regulating Factor 4: IRF4) is expressed by post germinal centre destined B cells.

-

MYC protein overexpression correlates with MYC gene translocation and identifies DLBCLs that are more aggressive, of worse prognosis and show a good response to R-CHOP (rituximab – cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) therapy.

6.9 Burkitt’s Lymphoma

-

1–2.5 % of NHLs.

-

Childhood or young adult: endemic/sporadic/HIV related (EBV: 95 %/15–20 %/30–40 % of cases respectively).

-

Jaw and orbit (early childhood/endemic), or abdomen (ileocaecal/late childhood or ovaries/young adult/sporadic) and breasts with risk of central nervous system involvement.

-

Monomorphic, medium-sized lymphoid cells, multiple small central nucleoli, basophilic cytoplasm.

-

Mitoses, apoptosis, “starry-sky” pattern.

-

CD79a, CD20, CD10, bcl-6, Ki-67 98–100 %, and bcl-2/tdt/CD5/23 negative.

-

t(8:14) and t(2:8)/t (8:22) variants. Demonstration of t(8:14) requires fresh tissue. Has a characteristic MYC translocation on in situ hybridization.

-

Requires aggressive polychemotherapy and is potentially curable: 90 % in low stage disease, 60–80 % with advanced disease, children better than adults. It can be difficult to distinguish from Burkitts like DLBCL.

6.10 Peripheral T Cell Lymphoma, Unspecified

-

10 % of NHLs and 30 % of T cell NHLs. Adults. Generalised lymph node or extranodal disease at presentation with involvement of skin, subcutaneous tissue, viscera and spleen. Aggressive with relapses but potentially curable.

-

Interfollicular/paracortical or diffuse infiltrate.

-

Variable nuclear morphology from medium sized centrocyte like to blast cells, “crows-feet” appearance with irregular nuclear contours.

-

Cytoplasmic clearing.

-

Accompanying eosinophils, histiocytes and vascularity with prominent post capillary venules.

-

Lymphoepithelioid variant (Lennert lymphoma).

-

Usually CD3, CD4, CD5 and TCR gene rearrangement positive, sometimes CD7/CD8/CD15/CD30/CD56/TIA-1.

-

Of worse prognosis than B cell lymphomas.

-

Variants:

-

Angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma (CD3, CD4, CD8, TCR (75 %), high endothelial venules, prominent dendritic cells). In adults with fever, skin rash and generalized lymphadenopathy. Moderately aggressive.

-

Mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome (usually CD3, CD5, TCR and CD4+/CD8−). Cutaneous patch, plaque and tumour stages with or without lymph node involvement. Indolent but stage related and can transform to high-grade NHL of large cell type. Sézary syndrome is more aggressive with peripheral blood involvement.

-

Enteropathy type T cell lymphoma (pleomorphic, CD3, associated gluten enteropathy or ulcerative jejunitis). Aggressive and in adults with abdominal pain, mass, ulceration or perforation, or a change in responsiveness to a gluten free diet.

-

Subcutaneous panniculitis like T cell lymphoma (nodules trunk/extremities, CD3, CD8, TCR). An 80 % 5 year survival but sometimes haemophagocytic syndrome supervenes with poor prognosis.

-

γδ hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma. Male adolescents and young adults. Aggressive and relapses despite treatment with survival <2 years. Liver, spleen and lymph node sinus involvement. CD3+, CD4/8−, γδ TCR.

-

6.11 Extranodal NK/T Cell Lymphoma, Nasal Type

-

Necrotising lethal midline granuloma. Also seen in skin and soft tissues. Aggressive with 30–40 % survival.

-

Polymorphic inflammatory infiltrate of eosinophils and histiocytes which may obscure the tumour cells.

-

Variably sized atypical lymphoid cells, EBV positive on in situ hybridisation.

-

Angiocentric and destructive.

-

Variably CD2, CD56, CD45R0, TCR−. Cytoplasmic but not surface CD3. Also ±CD57, perforin, granzyme B, TIA-1.

6.12 Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL)

-

2.5 % of NHLs in adults and 10–20 % of childhood malignant lymphomas.

-

Elderly and young (25 % <20 years): ALK negative and ALK positive/males, respectively.

-

May also follow mycosis fungoides, lymphomatoid papulosis or HL.

-

Cohesive, sinusoidal growth pattern of “epithelioid” cells mimicking carcinoma, malignant melanoma and germ cell tumour.

-

Large pleomorphic nuclei, multiple nucleoli, polylobated forms, “hallmark cells” with horseshoe or reniform nucleus; rarely small cell variant.

-

CD30, and, EMA/CD45/CD3±.

-

Mainly T (60–70 % TCR), B (0–5 %) and null (20–30 %) cell types. Ninety percent have clonal TCR rearrangements.

-

12–50 % of adult cases are t(2:5) and ALK-1 positivity confers a good prognosis (80 % 5 year survival) despite presentation with stage III/IV disease. ALK-1 negative cases have 40 % 5 year survival. Relapses are common (30 %) but treatable.

6.13 Precursor T Lymphoblastic Lymphoma/Leukaemia

-

CD3, CD4, CD8, CD43, Ki-67 >95 %, tdt. Presents in childhood/adolescence as leukaemia or a mediastinal mass (also lymph nodes, skin, liver, spleen, central nervous system, gonads). Aggressive with 20–30 % 5 year survival but potentially curable.

6.14 Granulocytic (Myeloid) Sarcoma

-

Myelomonocytic markers are CD68, myeloperoxidase, chloroactetate esterase, neutrophil elastase, lysozmye, CD15, CD34, CD43, CD117.

-

Megakaryocytic component: CD61, factor VIII.

-

If a tumour looks like a malignant lymphoma but does not show appropriate immunohistochemical marking, think of granulocytic (myeloid) sarcoma or plasma cell myeloma.

7 Extranodal Lymphoma

Of NHLs, 25–40 % are extranodal, defined as when a NHL presents with the main bulk of disease at an extranodal site usually necessitating the direction of treatment primarily to that site. In order of decreasing frequency sites of occurrence are

-

Gastrointestinal tract (especially stomach then small intestine)

-

Skin

-

Waldeyer’s ring

-

Salivary gland

-

Thymus

-

Orbit

-

Thyroid

-

Lung

-

Testis

-

Breast

-

Bone.

A majority are aggressive large B cell lymphomas although T cell lesions also occur (cutaneous T cell lymphoma, enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma, subcutaneous panniculitis like T cell lymphoma, NK/T cell sinonasal lymphoma). Their incidence is rising partly due to increased recognition and abandonment of terms such as pseudolymphoma, but also because of aetiological factors e.g. HIV, immunosuppression after transplantation or chemotherapy, autoimmune diseases (e.g. systemic lupus erythematosis), and chronic infections (H. pylorii, EBV, hepatitis C virus).

Many are low-grade in character with indolent behaviour, remaining localised to the site of origin. However a significant proportion present as or undergo high-grade transformation and when they metastasise typically do so to other extranodal sites. This site homing can be explained by the embryological development and circulation of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). The low-grade MALTomas often arise from a background of chronic antigenic stimulation:

Gastric lymphoma | H. pylorii gastritis |

Thyroid lymphoma | Hashimoto’s thyroiditis |

Salivary gland lymphoma | Lympho(myo-)epithelial sialadenitis/Sjögren’s syndrome. |

Their classification does not strictly parallel that of nodal lymphoma but mirrors marginal zone or monocytoid B cell lymphoma. They normally comprise a sheeted or nodular infiltrate of centrocyte like cells, destructive lymphoepithelial lesions and monotypic plasma cell immunoglobulin expression. Interfollicular infiltration or follicular colonisation of reactive follicles by the neoplastic cells is characteristic. There is often a component of blast cells and the immunophenotype is one of exclusion in that they are CD 5 and cyclin-D1 negative ruling out mantle cell lymphoma and other small B lymphocyte lymphoproliferative disorders. Other extranodal lymphomas have diverse morphology and immunophenotype correlating with the full spectrum of the WHO classification, although the lymph node based categories are not consistently transferable to extranodal sites.

Immunosuppressed post transplant (solid organs or bone marrow) patients are prone to a wide spectrum of nodal/extranodal EBV associated polyclonal and monoclonal B cell lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD). Three main categories exist: plasmacytic hyperplasia/infectious mononucleosis like (low-grade PTLD), polymorphic B cell hyperplasia/polymorphic B cell lymphoma (intermediate-grade PTLD) and monomorphic immunoblastic or centroblastic lymphoma/ multiple myeloma (high-grade PTLD). There is considerable overlap between the categories but in general monomorphic/monoclonal lesions are worse than polymorphic/polyclonal lesions. However even what appears to be high-grade lymphoma may potentially regress if immunosuppressant therapy is decreased. Serum titres and/or tissue expression of EBV are ascertained and clinical response to alteration of immunotherapy and anti-viral therapy assessed prior to use of chemotherapy. Similar findings can also be present in patients receiving chronic immunosuppression therapy for autoimmune and rheumatological disorders.

8 Prognosis

For some malignant lymphomas watchful waiting is the initial course of action and treatment is only instigated once the patient is symptomatic. Otherwise, chemotherapy and radiotherapy are the two principal treatment modalities for malignant lymphoma. However, surgical excision is often involved for definitive subtyping in primary lymph node disease, or, for removal of a bleeding or obstructing tumour mass and primary diagnosis of extranodal malignant lymphoma e.g. gastric lymphoma. Prognosis relates to lymphoma type/grade (small cell and nodular are better than large cell and diffuse), and stage of disease. Low-grade or indolent nodal malignant lymphomas have a high frequency (>80 % at presentation) of bone marrow and peripheral blood involvement. They are incurable pursuing a protracted time course and relapse at a late date (5–10 years) with potentially blast transformation (e.g. CLL: 23 % risk at 8 years). High-grade or aggressive lymphomas develop bone marrow or peripheral involvement as an indication of advanced disease and are fatal within 1–2 years if left untreated. Prior to this the majority show good chemoresponsiveness with complete remission in 80 % and potential cure in 60 %. Overall, four broad prognostic categories are identified in NHL, although outlook does vary within individual types e.g. grades 1/2 or 3 follicle centre (follicular) lymphoma:

NHL type | 5 year survival (%) |

|---|---|

1. Anaplastic large cell/MALT/follicular | >80 |

2. Nodal marginal zone/small lymphocytic/lymphoplasmacytoid | 60–80 |

3. Mediastinal B cell/large B cell/Burkitt’s | 30–70 |

4. T lymphoblastic/peripheral T cell/mantle cell | <50 |

Hodgkin’s malignant lymphoma is relatively radiotherapy and chemotherapy responsive. Prognosis relates to histological category (e.g. type 2 nodular sclerosis is worse than type 1), but more importantly, stage of disease which is also an important factor in treatment selection. Average 5 year survival and cure rates for HL are 75 % with worse outcome for older patients (> 40–50 years), disease of advanced stage (i.e. more than one anatomical site), involvement of the mediastinum by a large mass (>1/3 of the widest thoracic diameter), spleen or extranodal sites. Lymphocyte-depleted HL is least favourable with the mixed cellularity category being of intermediate outlook. Both usually present with high stage disease involving spleen, retroperitoneal nodes and abdominal organs. However, histological type is usually regarded as having prognostic value only in limited disease (stage I or II). HL has a bimodal age presentation (15–40 years, 60–70 years) with nodular sclerosis type in the head and neck of young people being the commonest (75 % of cases). About 25 % of patients have prognostically adverse B cell symptoms at presentation but the commonest complaint is painless cervical lymphadenopathy ± mediastinal disease. Disease usually involves contiguous, axial lymph node groups (neck, axilla, mediastinum, retroperitoneum, groin) with occasional extranodal involvement.

There is evidence that early (confined to the mucosa), low-grade gastric MALToma is potentially reversible on removal of the ongoing antigenic stimulus i.e. antibiotic treatment of H. pylorii. However, high-grade disease or low-grade lesions with deep submucosal or muscle invasion require chemotherapy supplemented by surgery if there are local mass effects e.g. bleeding or pyloric outlet stenosis. Prognosis of MALT derived NHL relates to the histological grade and stage of disease.

T cell lymphomas form a minority of NHL (10–15 %) and tend to have a worse prognosis than B cell lesions. Their cytological features are not particularly reliable at defining disease entities or clinical course, which is more dependent on tumour site and clinical setting. Involvement of extranodal sites and relapse there is not infrequent with typically an aggressive disease course e.g. enteropathy type T cell lymphoma and T/NK (angiocentric) sinonasal lymphoma. Cutaneous ALCL has a favourable prognosis while that of systemic ALCL with skin involvement is poor: 50 % present with stage III/IV disease and there is a 65–85 % 5 year survival rate but relapse is high (30–60 %).

Similarly some B cell lymphomas have site specific characteristics and clinical features e.g. mantle cell lymphoma in the gut (lymphomatous polyposis) or diffuse mediastinal large B cell lymphoma – young females with a rapidly enlarging mediastinal mass associated with superior vena cava syndrome. A large (>10 cm) mass and extramediastinal spread indicate poor prognosis. Generally adverse prognostic factors in NHLs are:

-

Age >60 years.

-

Male gender.

-

Systemic symptoms (fever >38 °C, weight loss >10 %, night sweats).

-

Poor performance status.

-

Anaemia

-

Elevated serum LDH.

-

Tumour bulk:

-

5–10 cm (stage I/II); > 10 cm (stage III/IV)

-

Large mediastinal mass

-

Palpable abdominal mass

-

Combined paraortic and pelvic nodal disease.

-

Combinations of these parameters can be scored in a clinical prognostic index to give risk and 5 year survival figures.

-

9 Other Malignancy

Carcinoma, germ cell tumours and malignant melanoma frequently metastasise to lymph nodes and are seen either in diagnostic biopsies (or FNAC) in patients with lymphadenopathy, or in regional lymph node resections in patients with known cancer. Spread of malignant mesothelioma or sarcoma to lymph nodes is unusual although it does occur e.g. alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, epithelioid sarcoma, synovial sarcoma. Assessment is by routine morphology supplemented by ancillary techniques e.g. immunohistochemistry and molecular methods, although it should be noted that the significance of nodal micrometastases in a number of cancers is still not resolved. Metastases are initially in the subcapsular sinus network expanding to partial or complete nodal effacement with potential for extracapsular spread. Anatomical site of involvement can be a clue as to the origin of the cancer e.g. neck (cancer of the upper aerodigestive tract, lung, breast, salivary glands or thyroid gland), supraclavicular fossa (lung, stomach, prostate, testis, ovary or breast cancer), axilla (breast, lung cancer or malignant melanoma), groin (cancer of the perineum or perianal area, cutaneous melanoma and rarely the pelvis) and retroperitoneum (germ cell tumour, genitourinary cancers). The metastatic deposit may be necrotic or cystic (e.g. squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, germ cell tumour in the retroperitoneum), resemble the primary lesion or be more or less well differentiated. Cell cohesion with nesting, necrosis, focal or sinusoidal distribution, solid lymphatic plugs of tumour and plentiful cytoplasm favour non-lymphomatous neoplasia although this is not always the case e.g. ALCL, or, DLBCL. In this respect a broad but basic panel of antibodies is crucial for accurate designation (e.g. cytokeratins, CD 45, CD 30, OCT3/4, S100, melan-A, chromogranin) occasionally supplemented by histochemistry (e.g. PAS diastase resistant mucin positivity, an organoid pattern of reticulin fibres). Some metastases also induce characteristic inflammatory responses e.g. squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck, large cell lung cancer and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (lymphocytes, leukaemoid reaction, eosinophils, granulomas) even mimicking HL. Some diagnostic clues are:

Malignant melanoma | Cell nests, eosinophilic nucleolus, spindle/epithelioid cells, melanin pigment, S100, HMB-45, melan-A. |

Germ cell tumour | Midline (mediastinum or retroperitoneum), elevated serum βHCG or AFP (± tissue expres- sion), PLAP/CD117 (seminoma), cytokeratins/CD30 (embryonal carcinoma). Also SALL4 and OCT3/4 (except yolk sac tumour). |

Lobular breast cancer | Sinusoidal infiltrate of sheeted, non-cohesive small cells, intracytoplasmic lumina, cytokeratins (CAM 5.2, AE1/AE3, CK7), GCDFP-15 and ER positive. Metastatic ductal cancer often has a nested pattern of larger cells with variable ER/Her-2 positivity (Grade 1 or 2 tumours will have a tubular component). |

Small cell carcinoma | Small (×2–3 the size of a lymphocyte), round to fusiform cells, granular chromatin, inconspicuous nucleolus, moulding, crush and DNA artifact, ± paranuclear dot CAM 5.2, and, chromogranin/synaptophysin/CD56/TTF-1 (Merkel cell carcinoma is CK 20 positive). In addition to positivity with the above markers other metastatic neuroendocrine tumours (e.g. carcinoid, large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma) show stronger chromogranin and cytokeratin expression than small cell carcinoma. |

Lung adenocarcinoma | Variably glandular or tubulopapillary, CK7/TTF-1/napsin-A/CEA/BerEP4/MOC31. |

Thyroid carcinoma | Papillae, characteristic nuclei (overlapping, optically clear, grooves), psammoma bodies, CK7/TTF-1 and thyroglobulin/CK19. |

Colorectal adenocarcinoma | Glandular with segmental and dirty necrosis, CK20/CEA/CDX-2/βcatenin. |

Upper gastrointestinal and pancreaticobiliary adenocarcinoma | Tubuloacinar, tall columnar cells with clear cytoplasm, CK7/CEA/CA19-9/± CK20/CDX-2. |

Ovarian carcinoma | Serous (tubulopapillary, psammoma bodies, CK7/CA125/WT-1/p16), or mucinous (glandular, CK7, ±CK20/CA125). |

Uterine adenocarcinoma | Endometrioid (CK7/vimentin/ER) or serous (CK7/p53/Ki-67/HMGA2/PTEN). |

Prostate adenocarcinoma | Acinar or cribriform, PSA m/p, PSAP/AMACR. |

Bladder carcinoma | Nested (squamoid) or micropapillary, CK7/CK20/34βE12/CK5/6/uroplakin III/GATA-3. |

m = monoclonal | p = polyclonal |

The reader is referred to the Introduction for further discussion of the use of immunohistochemistry.

Notes

- 1.

1Grade 1/grade 2 British National Lymphoma Investigation (BNLI).

- 2.

2See footnote 1.

Bibliography

Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE. Distinct types of large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403:503–11.

Banerjee SS, Verma S, Shanks JH. Morphological variants of plasma cell tumours. Histopathology. 2004;44:2–8.

Brady G, MacArthur GJ, Farrell PJ. Epstein-Barr virus and Burkitt lymphoma. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:1397–402.

Brown D, Gatter K, Natkunam Y. Bone marrow diagnosis: an illustrated guide. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell; 2006.

Brunning RD, Arber DA. Chapter 23. Bone marrow. In: Rosai J, editor. Rosai and Ackerman’s surgical pathology. 10th ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2011.

Bryant RJ, Banks PM, O’Malley DP. Ki-67 staining as a diagnostic tool in the evaluation of lymphoproliferative disorders. Histopathology. 2006;48:505–15.

Campo E, Chott A, Kinney MC, Leoncini L, Meijer CJLM, Papadimitriou CS, Piris MA, Stein H, Swerdlow SH. Update on extranodal lymphomas. Conclusions of the workshop held by the EAHP and the SH in Thessaloniki, Greece. Histopathology. 2006;48:481–504.

Chan JKC. Tumours of the lymphoreticular system, including spleen and thymus. In: Fletcher CDM, editor. Diagnostic histopathology of tumours, vol. 3. 3rd ed. London: Harcourt; 2007. p. 1139–310.

Chan JKC, Banks PM, Cleary ML, Delsol G, de Wolf-Peters C, Falini B, Gatter KC, Grogan TM, Harris NL, Isaacson PG, Jaffe ES, Knowles DM, Mason DY, Müller-Hermelink HK, Pileri SA, Piris MA, Ralfkiaer E, Stein H, Warnke RA. A proposal for classification of lymphoid neoplasms (by the International Lymphoma Study Group). Histopathology. 1994;25:517–36.

De Kerviler E, Guermazi A, Zagdanski AM, et al. Image-guided core-needle biopsy in patients with suspected or recurrent lymphoma. Cancer. 2000;89:647–52.

Delecluse H-J, Feederle R, O’Sullivan B, Taniere P. Epstein-Barr virus-associated tumours: an update for the attention of the working pathologist. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:1358–64.

DeLeval L, Harris NL. Variability in immunophenotype in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and its significance. Histopathology. 2003;43:509–28.

Du M-Q, Bacon CM, Isaacson PG. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8 and lymphoproliferative disorders. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:1350–7.

Grogg KL, Miller RF, Dogan A. HIV infection and lymphoma. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:1365–72.

Hall JG. The functional anatomy of lymph nodes. In: Stansfield AG, d’Ardenne AJ, editors. Lymph node biopsy interpretation. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1992. p. 3–28.

Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, Gascoyne RD, Delabie J, Ott G, Műller-Hermelink HK, Campo E, Braziel RM, Jaffe ES, Pan Z, Farinha P, Smith LM, Falini B, Banham AH, Rosenwald A, Staudt LM, Connors JM, Armitage JO, Chan WC. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood. 2004;103:275–82.

Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H, et al. A revised European- American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 1994;84:1361–92.

Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, Flandrin G, Műller-Hermelink HK, Vardiman J, Lister TA, Bloomfield CD. The World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the haemopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the clinical advisory committee meeting, Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. Histopathology. 2000;36:69–87.

Hermans J, Krol AD, van Groningen K, et al. International Prognostic Index for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is valid for all malignancy grades. Blood. 1995;86:1460–3.

Isaacson PG. Haematopathology practice: the commonest problems encountered in a consultation practice. Histopathology. 2007;50:821–34.

Kapatai G, Murray P. Contribution of the Epstein-Barr virus to the molecular pathogenesis of Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:1342–9.

Kluin PM, Feller A, Gaulard P, Jaffe ES, Meijer CJ, Műller-Hermelink HK, Pileri S. Peripheral T/NK-cell lymphoma: a report of the IXth workshop of the European Association for haematopathology. Histopathology. 2001;38:250–70.

Kocjan C. Cytological and molecular diagnosis of lymphoma. ACP Best Practice No 185. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:561–7.

Leoncini L, Delsol G, Gascoyne RD, Harris NL, Pileri SA, Piris MA, Stein H. Aggressive B-cell lymphomas: a review based on the workshop of the XI meeting of the European Association for Haematopathology. Histopathology. 2005;46:241–55.

Maes B, De Wolf-Peeters C. Marginal zone cell lymphoma – an update on recent advances. Histopathology. 2002;40:117–26.

Matutes E. Adult T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:1373–7.

Műller-Hermelink HK, Zettl A, Pfeifer W, Ott G. Pathology of lymphoma progression. Histopathology. 2001;38:285–306.

O’Malley DP, George TI, Orazi A, editors. Benign and reactive conditions of lymph node and spleen. Washington D.C.: ARP Press; 2009.

Oudejans JJ, van der Walk P. Diagnostic brief. Immunohistochemical classification of B cell neoplasms. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:193.

Prakash S, Swerdlow SH. Nodal aggressive B-cell lymphomas: a diagnostic approach. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:1076–85.

Rosai J. Chapter 22. Lymph nodes, spleen. In: Rosai J, editor. Rosai and Ackerman’s surgical pathology. 10th ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2011.

Sagaert X, De Wolf-Peeters C. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Curr Diagn Pathol. 2003;9:252–8.

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Vardiman JW. WHO classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics. Tumours of haemopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC Press; 2008.

Tapia G, Lopez R, Munoz-Marmol AM, Mate JL, Sanz C, Marginet R, Navarro J-T, Ribera J-M, Ariza A. Immunohistochemical detection of MYC protein correlates with MYC gene status in aggressive B cell lymphomas. Histopathology. 2011;59:672–8.

Taylor CR. Hodgkin’s disease is a non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:1–4.

The National Cancer Action Team and The Royal College of Pathologists. Additional Best Practice Commissioning Guidance for developing Haematology Diagnostic Services. In line with the NICE Improving Outcomes Guidance for Haemato-oncology 2003. Accessed at http://www.ncat.nhs.uk.

The Royal College of Pathologists and The British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Best Practice in Lymphoma Diagnosis and Reporting – Specific Disease Appendix. Accessed at http://www.rcpath.org/index.asp?PageID=254.

Viswanatha DS, Dogan A. Hepatitis C virus and lymphoma. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:1378–83.

Warnke RA, Weiss LM, Chan JKC, Cleary ML, Dorfman RF. Tumors of the lymph nodes and spleen. Atlas of tumor pathology. 3rd series. Fascicle 14. Washington: AFIP; 1995.

Wilkins BS. Pitfalls in lymphoma pathology: avoiding errors in diagnosis of lymphoid tissues. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:466–76.

Wilkins BS, Wright DH. Illustrated pathology of the spleen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000. p. 1–31.

Wittekind CF, Greene FL, Hutter RVP, Klimpfinger M, Sobib LH. TNM atlas: illustrated guide to the TNM/pTNM classification of malignant tumours. 5th ed. Berlin: Springer; 2005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer-Verlag London

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Allen, D.C. (2013). Nodal Malignant Lymphoma (with Comments on Extranodal Malignant Lymphoma and Metastatic Cancer). In: Histopathology Reporting. Springer, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-5263-7_35

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-5263-7_35

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-4471-5262-0

Online ISBN: 978-1-4471-5263-7

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)