Abstract

Bisphosphonates inhibit normal and pathological bone resorption by osteoclasts. These drugs reduce osteoclast binding to the bone, decrease the production of new osteoclasts, and stimulate osteoclast apoptosis. Bisphosphonates also have antiangiogenic properties. This results in a decreased bone turnover, with hypermineralization and bone hypovascularization. Combination of a compact and avascular bone is believed to result in osteonecrosis by a mechanism of ischemia and secondary infection. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) affects the mandible and maxilla almost exclusively, with the mandible two times more likely to be affected than the maxilla. Although it is unclear why the jaw is particularly vulnerable to this condition, putative reasons include high bone turnover because of microtrauma from mastication, high bone density of the jaw, and the susceptibility to infection because of close proximity to the oral cavity. The therapeutic goals in BRONJ are preservation of the quality of life and management and prevention of pain, infection, and progression of lesions. Complication rates after microvascular reconstruction using a free flap in the treatment of BRONJ seem acceptable. Most patients enjoy good to excellent functional and aesthetic results after free-flap reconstruction. We believe segmental resection and microvascular reconstruction may be a valid option in select advanced cases of BRONJ and that the treatment algorithm of these cases may be redefined in the near future.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

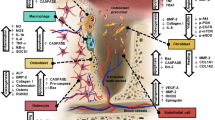

Bisphosphonates are synthetic analogues of the endogenous substance pyrophosphate (a normal constituent of the bone matrix), which inhibit bone resorption and thus have a hypocalcemic effect [1,2,3]. Bisphosphonates are a relatively novel class of agents that have been increasingly recommended for use in patients suffering osteoporosis, Paget’s disease of bone, hypercalcemia of malignancy, osteolytic bone metastases, and osteolytic lesions of multiple myeloma [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Several medicines are available in the United States with different indications, dosage, administration, and potency (Table 1). Despite the benefits related to their use, osteonecrosis of the jaws represents a complication in a subset of patients receiving these treatments, especially when administered intravenously and following dentoalveolar surgery [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. In this condition, the affected bones become friable, nonviable, and eventually exposed [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. The oral complications can have negative impact on quality of life by affecting eating, speaking, and maintenance of oral hygiene [18]. The first complications were described in 2003, few years later their approval, and nowadays, although more than 950 articles have been published, pathophysiology remains to be well elucidated [23]. In 2003, Marx described 36 cases of exposed necrotic bone in patients suffering tumors who had been treated with intravenous bisphosphonates, and in 2004, Ruggiero reported further 63 cases [23, 24, 38, 39]. Several cells are implicated in bone metabolism including osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and osteocytes, and at this time osteoclasts represent the main cellular target; specifically bisphosphonates provide downregulation of osteoclasts thus repressing bone remodeling, but their effects on osteocytes remain controversial [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. It is accepted that osteoblasts activity remains unalterated. The basic premise of this hypothesis is that the jaw has a high remodeling rate and bisphosphonates suppress remodeling [40,41,42,43,44,45]. It is also clear that remodeling within the intracortical envelope is considerably higher in the jaw compared with other skeletal sites. As a consequence the bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis (BRON) follows the idea that since remodeling is higher in the jaw and bisphosphonates suppress remodeling, then this plays a role in the pathophysiology of osteonecrosis [45,46,47,48,49,50]. Intravenous bisphosphonate treatment seems to pose a greater risk of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) than oral administration, though oral treatment longer than 3 years may increase the risk [50,51,52,53]. Since dentoalveolar surgery is a precipitating factor, preventive measures include maintaining good oral hygiene and undertaking any necessary dental treatment before beginning a course of intravenous bisphosphonate treatment [30,31,32,33,34,35]. Some clinical guidelines recommend that people at risk of BRONJ should take a 3-month break from oral bisphosphonates before and after dental treatment [37,38,39]. Greater drug strength, longer duration of use, older age, and a history of inflammatory dental disease are associated with a higher risk of BRONJ. The true incidence of BRONJ is unknown. Reported rates range from 0.028% to 18.6% depending on indication for treatment, study population, and sample size [53]. Osteonecrosis is found more commonly in the mandible than the maxilla (2:1 ratio) and more commonly in areas with thin mucosa overlying bony prominences such as lingual and palatal tori, bony exostoses, and the mylohyoid ridge [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. The following factors are thought to be risk factors for BRONJ: corticosteroid therapy, diabetes, smoking, alcohol use, poor oral hygiene, and chemotherapeutic drugs [53].

2 Diagnostic Criteria

According to the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons Position Paper, patients can be considered suffering BRONJ if all the following three characteristics are present at the same time:

-

1.

Current or previous treatment with bisphosphonates

-

2.

Exposed bone in the maxillofacial area persisting for more than 8 weeks

-

3.

No history of radiotherapy to the jaws [1]

Differential diagnosis remains the main topic in order to identify the proper treatment, and in particular the following conditions must be excluded: alveolar osteitis, sinusitis, gingivitis/periodontitis, caries, periapical pathology, and temporomandibular joint disorders [1, 53]. BRONJ may be asymptomatic or present with pain, swelling, loose teeth, and altered sensation [1]. Other medications (denosumab, bevacizumab, cabozantinib, sunitinib) have also been associated with jaw osteonecrosis, the condition then being called medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) [53]. Beyond clinical assessment according to the above criteria, radiographic exams are necessary to stage the disease, and in particular orthopantomography, CT scans of the maxillofacial skeleton with contrast medium and magnetic resonance imaging are recommended [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11].

3 Osteonecrosis Management

There is currently no “gold standard” of treatment for BRONJ [1, 53]. Interventions used to treat this complication are diverse, controversial, and largely empirical. Three broad categories of interventions have been described: classical “wound-healing” conservative treatment, diverse surgical techniques, and different “add-on” treatments [1, 53]. These three approaches are often used in combination, either at the same time or in succession, and are elucidated in Table 2. Strategies for the management of patients suffering BRON have been defined by the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons in the Position Paper on Bisphosphonates-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw and approved by the Board of Trustees in September 2006 [1]. The position paper was developed by a task force appointed by the Board and composed of clinicians with extensive experience in treating these patients and basic science researchers. The knowledge base and experience in addressing BRON have expanded, thus requiring modifications and refinements to the original paper [1,2,3,4]. The task force was then called again in 2008 to revise the recommendations previously published in 2006. This update contains revisions to the diagnosis and staging and management strategies and highlights the status of basic science research (Table 3). Despite this, these recommendations are not widely followed, and several therapeutic strategies have been recommended in the literature according to the severity of this complication, ranging from strictly conservative to aggressive surgical approaches [53]. At-risk patients and asymptomatic patients have been identified including proper prophylactic measurements as listed in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. The treatment of BRONJ is still under debate, and most reports show different outcomes. For this reason, a systematic review of the available literature was made in order to assess which treatment has a higher success rate in patients diagnosed with BRONJ by Comas-Calonge and co-workers [53]. In this research the author considered the treatment successful when the patient improved the stage of the disease or when there was absence of bone exposure with proper healing and the patient remained asymptomatic without any clinical signs of infection. They referred several limitations including the lack of standardized success criteria and treatment protocols, the use of different surgical approach (sequestrectomy vs. bone resection), and the association of several antibiotics and antiseptics. Nonetheless the success rates of BRONJ surgical treatment vary between 58% and 100%. The main advantage of sequestrectomy is an expected superior healing process since unaffected periosteum is preserved. Tension-free closure of the wound and an adequate bone resection are key factors for the treatment prognosis [53]. Although it is extremely difficult to quantify the amount of bone that should be removed, bleeding is considered a sign of healthy bone [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. Some authors proposed a more aggressive management, based in bone resections, to treat BRONJ patients, in the idea that, regardless of the stage of the disease, areas of the necrotic bone that are a constant source of soft tissue irritation should be removed in order to allow a proper healing [50,51,52,53].

4 Reconstructive Microsurgery

For the management of exposed necrotic bone, additional surgical debridement or sequestrectomy with primary mucosal closure seems to be effective in most cases [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. If there are recurrences at the conservative treatment, then osteotomies should be considered as it seems to be more successful than wound debridement alone [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. The reconstruction of subtotal mandibulectomy defects requires the vascularized bone to promote healing and provide adequate soft tissue support and oral competence [34]. Patients with reasonable life expectancy with regard to their malignant disease should be considered for microvascular tissue transfer after aggressive resection of the affected region [5]. The effect of the transferred flap with a new input of blood supply might be one of the reasons for the uneventful postoperative in all patients; moreover the cutaneous component provides additional health tissue useful to achieve successful reconstruction by establishing a tension-free closure of the intraoral defect [52]. Finally it gives also the opportunity of oral prosthetic rehabilitation using dental implants, as described by Ferrari et al. (2008) [15]. After an observation period of 12 months from microsurgical reconstruction of the jaws, high survival rates can be expected with few recurrences of osteonecrosis [53]. This, in turn, means that vascularized fibula flap has been a well-accepted method to reconstruction, and despite the limited number of publications, this treatment appears to be practicable in BRONJ-resected patients and doesn’t seem to influence the natural course of the primary disease [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53].

According to the best of our knowledge, there have been 37 cases of stage III BRONJ treated with free-flap reconstruction in the published literature (Table 6). Radiographic imaging with CT, cone beam, and/or orthopantomogram was obtained during follow-up in all patients. Flap failure occurred in two cases from the fibula, and a second flap was constructed from additional tissue during a second procedure [44, 50]. Fistulas formed in four cases making it the most common complication observed across studies [44]; BRONJ recurred in the contralateral jaw in two cases [12, 30]. Nonunion as reported by Nocini et al. [30] can occur because the resected margins were not free of disease; this finding was not evident during surgery and was found during histological evaluation of the resected tissue.

Some authors have stated that “aggressive” surgery, in this case resection and reconstruction with a free flap, is inappropriate because of the diminished life expectancy, poor general condition, and concomitant medications, such as steroids or chemotherapy, that can interfere with the postoperative result of patients with advanced BRONJ and the overall success of conservative measures and minimal surgical procedures [53]. Diminished life expectancy is certainly a theoretical concern given that most people who received intravenous bisphosphonates in our and others’ reviews had metastatic cancer to the bone or malignancy-related hypercalcemia [52, 53].

The main concerns, just theoretical, regard the possible transfer of sicked tissue into the oral cavity in patients suffering disseminated disease, but this is not been described yet. Indeed, one patient in the Seth et al. series died 8 weeks after reconstruction surgery in consequence of cancer-related complications [50,51,52,53]. On the other hand, most patients among published reports survived at least 12 months and many for at least several years after surgery suggesting that health status alone should not be an absolute contraindication to this procedure.

5 Outcome Measurements

Primary outcomes of proper management include healing of the osteonecrosis as indicated by one or more of the six indicators listed in Table 7; secondary outcomes are important indicators and listed in Table VII. Patients need close follow-up every 3 months for monitoring intraoral or extraoral symptoms along with radiographic examination (Table 8).

6 Proposed Flowchart

Our flowchart to surgical management differs according to the mandible and maxilla (Fig. 1). For bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis stage 0 and stage 1, we propose curettage, sequestrectomy, and marginal mandibulectomy according to the extension of bone resection, and this is applied both to mandible and maxilla. Stage 2 and stage 3 are managed according to site (maxillary/mandible) and patient’s performance status; mandible bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis stage 2 and stage 3 affecting patients with poor performance status are managed with segmental mandibulectomy without reconstruction (Figs. 2, 3, and 4); in case of good performance status, reconstruction is performed with free fibula flap for longer defects (Figs. 5, 6, and 7) and with medial femoral condylar flap for small defects (Figs. 7, 8, and 9). Maxillary stage 2 and stage 3 are managed with hemimaxillectomy and Bichat fat flap/temporalis muscle flap in case of good performance status (Figs. 9 and 10).

7 Future Research

The National Institute of Health has provided fundings to researchers in order to elucidate the pathophysiology of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw. The researchers focused on different aspects of this entity including but not limited to (a) the effect of bisphosphonates on intraoral soft tissue healing, (b) alveolar bone hemostasis, (c) antiangiogenic properties of bisphosphonate, (d) pharmacogenetic research, and (e) risk assessment tools. Novel strategies to improve prevention and treatment of BRON need to be developed and discussed in a proper manner. In the meantime, the 2014 update favors the term medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw instead of BRONJ to accommodate the growing number of osteonecrosis cases involving the maxilla and mandible associated with other antiresorptive (denosumab) and antiangiogenic therapies. Denosumab is an antiresorptive agent that exists as a fully humanized antibody against receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand and inhibits osteoclast function and associated bone resorption. It is administered subcutaneously every 6 months to decrease the risk of vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fractures in osteoporotic patients and administered monthly in metastatic bone disease from solid tumors. Denosumab is superior to zoledronic acid in preventing complications for patients with bone metastases. However, further studies are still needed to assess longer-term safety and efficacy of denosumab [53].

References

Advisory Task Force on Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws. America Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (2007) American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 65:369–376

Agrillo A, Ungari C, Filiaci F, Priore P, Iannetti G (2007) Ozone therapy in the treatment of avascular bisphosphonate-related jaw osteonecrosis. J Craniofac Surg 18(5):1071

Allen MR, Burr DB (2008) Mandible matrix necrosis in beagle dogs after 3 years of daily oral bisphosphonate treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 66:987–994

Allen MR, Follet H, Khurana M, Sato M, Burr DB (2006) Antiremodeling agents influence osteoblast activity differently in modeling and remodelling sites of canine rib. Calcif Tissue Int 79:255–261

Allen MR, Iwata K, Phipps R, Burr DB (2006) Alterations in canine vertebral bone turnover, microdamage accumulation, and biomechanical properties following 1-year treatment with clinical treatment doses of risedronate or alendronate. Bone 39:872–879

Anthony JP, Foster RD (1996) Mandibular reconstruction with the fibula osteocutaneous free flap. Oper Tech Plast Reconstr Surg 3(4):233–240

Arantes HP, Silva AG, Lazaretti-Castro M (2010) Bisphosphonates in the treatment of metabolic bone diseases. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metab 54:206–212

Assael LA (2007) New foundations in understanding osteonecrosis of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 62:125–126

Boyce RW, Paddock CL, Gleason JR, Sletsema WK, Eriksen EF (1995) The effects of risedronate on canine cancellous bone remodeling: three-dimensional kinetic reconstruction of the remodeling site. J Bone Miner Res 10:211–221

Buchbinder D, St. Hilaire H (2006) The use of free tissue transfer in advanced osteoradionecrosis of the mandible. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 64:961–964

Duncan MJ, Manktelow RT, Zuker RM, Rosen IB (1985) Mandibular reconstruction in the radiated patient: the role of osteocutaneous free tissue transfers. Plast Reconstr Surg 76:829–840

Engroff LS, Kim DD (2007) Treating bisphosphonate osteonecrosis of the jaws: is there a role for resection and vascularized reconstruction? J Oral Maxillofac Surg 65:2374–2385

Eriksen EF, Melsen F, Sod E, Barton I, Chines A (2002) Effects of long-term risedronate on bone quality and bone turnover in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Bone 31:620–625

Farrugia MC, Summerlin DJ, Krowiak E, Huntley T, Freeman S, Borrowdale R, Tomich C (2006) Osteonecrosis of the mandible or maxilla associated with the use of new generation bisphosphonates. Laryngoscope 116:115–120

Ferrari S, Bianchi B, Savi A, Poli T, Multinu A, Balestreri A (2008) Fibula free flap with endosseous implants for reconstructing a resected mandible in bisphosphonate osteonecrosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 66:999–1003

Gliklich R, Wilson J (2009) Epidemiology of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: the utility of a national registry. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 67(Sp. Iss. 5):71–74

Goodacre TE, Walker CJ, Jawad AS, Jackson AM, Brough MD (1990) Donor site morbidity following osteocutaneous free fibula transfer. Br J Plast Surg 43:410–412

Greenberg MS (2004) Intravenous bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 98:259–260

Griz L, Caldas G, Bandeira C, Assunção V, Bandeira F (2006) Paget’s disease of bone. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 50:814–822

Hsu CC, Chuang YW, Lin CY, Huang YF (2006) Solitary fibular metastasis from lung cancer mimicking stress fracture. Clin Nucl Med 31:269–271

Iwata K, Li J, Follet H, Phipps RJ, Burr DB (2006) Bisphosphonates suppress periosteal osteoblast activity independently of resorption in rat femur and tibia. Bone 39:1053–1058

Khosla S, Burr D, Cauley J, Dempster DW, Ebeling PR, Felsenberg D, Gagel RF, Gilsanz V, Guise T, Koka S, McCauley LK, McGowan J, McKee MD, Mohla S, Pendrys DG et al (2007) Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res 22:1479–1491

Marx RE (2003) Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 61:1115–1117

Marx RE, Cillo JE Jr, Ulloa JJ (2007) Oral bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis: risk factors, prediction of risk using serum CTX testing, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 65:2397–2410

Marx RE, Sawatari Y, Fortin M, Broumand V (2005) Bisphosphonate-induced exposed bone (osteonecrosis/osteopetrosis) of the jaws: risk factors, recognition, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 63:1567–1575

Mashiba T, Hirano T, Turner CH, Forwood MR, Johnston CC, Burr DB (2000) Suppressed bone turnover by bisphosphonates increases microdamage accumulation and reduces some biomechanical properties in dog rib. J Bone Miner Res 15(4):613–620

McDonald MM, Dulai S, Godfrey C, Amanat N, Sztynda T, Little DG (2008) Bolus or weekly zoledronic acid administration does not delay endochondral fracture repair but weekly dosing enhances delays in hard callus remodeling. Bone 43:653–662

Migliorati CA (2003) Bisphosphonates and oral cavity avascular bone necrosis. J Clin Oncol 21:4253–4254

Mücke T, Haarmann S, Wolff KD, Hölzle F (2009) Bisphosphonate related osteonecrosis of the jaws treated by surgical resection and immediate osseous microvascular reconstruction. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 37:291–297

Nocini PF, Saia G, Bettini G, Ragazzo M, Blandamura S, Chiarini L, Bedogni A (2009) Vascularized fibula flap reconstruction of the mandible in bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis. Eur J Surg Oncol 35:373–379

Plotkin LI, Aguirre JI, Kousteni S, Manolagas SC, Bellido T (2005) Bisphosphonates and estrogens inhibit osteocyte apoptosis via distinct molecular mechanisms downstream of extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. J Biol Chem 280:7317–7325

Plotkin LI, Weinstein RS, Parfitt AM, Roberson PK, Manolagas SC, Bellido T (1999) Prevention of osteocyte and osteoblast apoptosis by bisphosphonates and calcitonin. J Clin Invest 104:1363–1374

Reiriz AB, De Zorzi PM, Lovat CP (2008) Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaw: a case report. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 63:281–284

Rodan GA, Fleisch HA (1996) Bisphosphonates: mechanisms of action. J Clin Invest 97:2692–2696

Rosen HN, Moses AC, Garber J, Iloputaife ID, Ross DS, Lee SL, Greenspan SL (2000) Serum CTX: a new marker of bone resorption that shows treatment effect more often than other markers because of low coefficient of variability and large changes with bisphosphonate therapy. Calcif Tissue Int 66:100–103

Rosen HN, Moses AC, Garber J, Ross DS, Lee SL, Greenspan SL (1998) Utility of biochemical markers of bone turnover in the follow-up of patients treated with bisphosphonates. Calcif Tissue Int 63:363–368

Rosenberg TJ, Ruggiero S, Mehrotra O, Engroff SL (2003) Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with the use of bisphosphonates. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 61(Suppl 1):60

Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Assael LA, Landesberg R, Marx RE, Mehrotra B (2009) Task force on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws, American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw—2009 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 35:119–130

Ruggiero SL, Mehrotra B, Rosenberg TJ, Engroff SL (2004) Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with the use of bisphosphonates: a review of 63 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 62:527–534

Russell RG, Watts NB, Ebetino FH, Rogers MJ (2008) Mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates: similarities and differences and their potential influence on clinical efficacy. Osteoporos Int 19:733–759

Russell RG, Xia Z, Dunford JE, Oppermann U, Kwaasi A, Hulley PA, Kavanagh KL, Triffitt JT, Lundy MW, Phipps RJ, Barnett BL, Coxon FP, Rogers MJ, Watts NB, Ebetino FH (2007) Bisphosphonates: an update on mechanisms of action and how these relate to clinical efficacy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1117:209–257

Santamaria M Jr, Fracalossi AC, Consolaro MF, Consolaro A (2010) Influence of bisphosphonates on alveolar bone density: a histomorphometric analysis. Braz Oral Res 24:309–315

Sarathy AP, Bourgeois SL Jr, Goodell GG (2005) Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws and endodontic treatment: two case reports. J Endod 31:759–763

Seth R, Futran ND, Alam DS, Knott PD (2010) Outcomes of vascularized bone graft reconstruction of the mandible in bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Laryngoscope 120:2165–2171

Urken ML (1991) Composite free flaps in oromandibular reconstruction. Review of the literature. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 117:724–732

Vescovi P, Merigo E, Meleti M, Fornaini C, Nammour S, Manfredi M (2007) Nd:YAG laser biostimulation of bisphosphonate-associated necrosis of the jawbone with and without surgical treatment. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 45:628–632

Wang J, Goodger NM, Pogrel MA (2003) Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with cancer chemotherapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 61:1104–1107

Colletti G, Autelitano L, Rabbiosi D, Biglioli F, Chiapasco M, Mandalà M, Allevi F (2014) Technical refinements in mandibular reconstruction with free fibula flaps: outcome-oriented retrospective review of 99 cases. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 34(5):342–348

Ghazali N, Collyer JC, Tighe JV (2013) Hemimandibulectomy and vascularized fibula flap in bisphosphonate-induced mandibular osteonecrosis with polycythaemia rubra vera. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 42:120–123

Bedogni A, Saia G, Bettini G, Tronchet A, Totola A, Bedogni G, Ferronato G, Nocini PF, Blandamura S (2011) Long-term outcomes of surgical resection of the jaws in cancer patients with bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis. Oral Oncol 47:420–424

Spinelli G, Torresetti M, Lazzeri D, Zhang YX, Arcuri F, Agostini T, Grassetti L (2014) Microsurgical reconstruction after bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: our experience with fibula free flap. J Craniofac Surg 25:788–792

Sacco R, Sacco G, Acocella A, Sale S, Sacco N, Baldoni E (2011) A systematic review of microsurgical reconstruction of the jaws using vascularized fibula flap technique in patients with bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis. J Appl Oral Sci 19:293–300

Neto T, Horta R, Balhau R, Coelho L, Silva P, Correia-Sá I, Silva Á (2016) Resection and microvascular reconstruction of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: the role of microvascular reconstruction. Head Neck 38(8):1278–1285

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Spinelli, G., Arcuri, F., Valente, D., Raffaini, M., Agostini, T. (2018). Reconstructive Surgery Following Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws: Evolving Concepts. In: Shiffman, M., Low, M. (eds) Plastic and Thoracic Surgery, Orthopedics and Ophthalmology. Recent Clinical Techniques, Results, and Research in Wounds, vol 4. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/15695_2017_70

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/15695_2017_70

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-10709-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-10710-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)