Abstract

There is widespread recognition that higher education institutions (HEIs) must actively support commencing students to ensure equity in access to the opportunities afforded by higher education. This role is particularly critical for students who because of educational, cultural or financial disadvantage or because they are members of social groups currently under-represented in higher education, may require additional transitional support to “level the playing field.” The challenge faced by HEIs is to provide this “support” in a way that is integrated into regular teaching and learning practices and reaches all commencing students. The Student Success Program (SSP) is an intervention in operation at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) designed to identify and support those students deemed to be at risk of disengaging from their learning and their institution. Two sets of evidence of the impact of the SSP are presented: First, its expansion (a) from a one-faculty pilot project (Nelson et al. in Stud Learn Eval Innov Dev 6:1–15, 2009) to all faculties and (b) into a variety of applications mirroring the student life cycle; and second, an evaluation of the impact of the SSP on students exposed to it. The outcomes suggest that: the SSP is an example of good practice that can be successfully applied to a variety of learning contexts and student enrolment situations; and the impact of the intervention on student persistence is sustained for at least 12 months and positively influences student retention. It is claimed that the good practice evidenced by the SSP is dependent on its integration into the broader First Year Experience Program at QUT as an example of transition pedagogy in action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The notion of engagement underpins student learning in terms of persistence, achievement and retention (see for example Crosling et al. 2009; Lodge 2010; Scott et al. 2009; Simeoni 2009 for recent reviews). If engagement is the linchpin of student success and retention, then HEIs need to monitor and measure the extent of student engagement—particularly in the first year—and most importantly intervene with students exhibiting signs of disengaging from their studies. James et al. (2010), reporting in an Australian tertiary context, concluded that “there is perhaps no greater challenge facing the sector than that of identifying and monitoring the students who are ‘at risk’ of attrition or poor academic progress” but simultaneously noted that “limited inroads have been made into this problem” (p. 102). Similar concerns have been expressed globally—in North America: “In spite of the attention paid to retaining students, we have made very little progress…. Our efforts… have been less than successful” (Coley and Coley 2010, p. 2); and the United Kingdom: While “higher education in England achieves high levels of student retention … there is scope for some further improvements” (The National Audit Office 2007, para 20, 21).

Against this background, it is becoming increasingly accepted that HEIs and their teaching and support staff have an obligation to provide the necessary mileau to support students to engage academically, socially and personally with their institution (Bradley et al. 2008; Coley and Coley 2010; Gillard 2010; Tinto 2009). Within this social justice paradigm, and in attempting to address the challenge and related concerns expressed above, comes the entreaty for “the need for better retention strategies” (Coley and Coley 2010, p. 3) stressing “the importance for institutions of implementing carefully designed monitoring and preventative procedures that can track student progress, identifying at risk students, and putting in place conditions which may support and inspire student success” (Australian Council for Educational Research [ACER] 2009, p. 44).

Identifying and supporting at-risk commencing students

In attempting to address this issue and using conference presentations as an indicative cutting-edge source, there is clear evidence of an increase in the development and implementation of a plethora of engagement and retention initiatives. See for example the proceedings of the Pacific Rim First Year in Higher Education Conference and the associated journal The International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education (follow links from http://www.fyhe.qut.edu.au/), the European First Year Experience Conference (http://www.efye.eu/) and the International Conference on First Year Experience (http://sc.edu/fye/ifye/). The quality and extent of the programs vary considerably from small scale pilot studies (e.g. Johnston et al. 2010; Potter and Parkinson 2010) to more extensive projects (e.g. Carlson and Holland 2009; Wilson and Lizzio 2008) with the latter approaching a proactive, engaging and supportive philosophy and a whole-of-institution involvement. Adams et al. (2010) reporting on student attrition, benchmarked the retention practices in 17 Australian tertiary institutions (12 of which were public universities including the institution reported on here) and identified the attributes of good practice and effective retention performance. Coley and Coley (2010) define these attributes as “successful campus-wide retention programs” where the institutions “have determined a clear methodology to define and identify ‘at-risk’ students, to reach out to students with appropriate resources and support, and to track and monitor student engagement” (p. 6).

While acknowledgement and awareness of, and the desire to implement, such an interventionist approach are omnipresent, actual examples are scarce as indicated by the aforementioned conference proceedings, sector analysis by Adams et al. (2010) and the “limited inroads” assessment of James et al. (2010). What is reported here is the latest evidence from just such a program, the Student Success Program (SSP)Footnote 1 at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) in Brisbane, Australia. The SSP is one of the key activities in QUT’s First Year Experience Program (FYEP) (Kift et al. 2010) (http://www.fye.qut.edu.au/). It is facilitated by good practice in curriculum design and engagement, academic-professional partnerships and a governance infrastructure which includes a first year experience (FYE) policy (http://www.mopp.qut.edu.au/C/C_06_02.jsp) and a university level committee with the responsibility for first year student success and retention.

Early evidence of the impact of an SSP pilot in one faculty at QUT has been reported elsewhere (Nelson et al. 2009) and is summarised briefly below. This report builds on that by detailing:

-

1.

the expansion of the program to (a) all faculties and (b) other applications (“campaigns”) reflecting the total student enrolment experience; and

-

2.

the impact of the of SSP on student progression.

The Student Success Program

Overview

After a 2007 investigation into the efficacy of monitoring and personalising contact with first year students deemed to be at-risk of disengaging from their studies (Duncan and Nelson 2008) and a gap analysis of the systems, processes and resources required to identify, monitor and provide timely support interventions for such students, the SSP was piloted in 2008 and subsequently implemented as part of the TIP (Nelson et al. in press). The SSP is an intervention designed to identify students at risk of disengaging before they fail unitsFootnote 2 or drop out of first year university studies. It aims to decrease commencing student attrition and enhance their experience, and is particularly important for those students for whom successful transition involves greater challenges.Footnote 3 The focus of the SSP

is to create bridges for [at-risk] students between their classroom experiences and the discipline and specialist support services available to assist them with their learning and/or their management of issues that may be interfering with their ability to focus on their learning and engagement. (Nelson et al. 2009, p. 3)

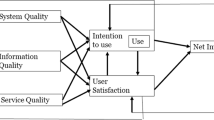

Vital to the SSP is the custom-built Contact Management System (CMS) called OutReach. System interfaces have been built to retrieve data available within other student systems and to import data from external sources (e.g. attendance rolls). OutReach supports SSP operations and reporting as well as the evaluation of the impact of SSP interventions. Students at-risk of disengaging are identified through a consolidated view of their profile based on a range of descriptive and academic indicators including cohort membership, attendance, participation in face-to-face and online activities, and submission (or not) of assessment items followed by the pass/failure marks for these items.

Proactive highly individualised contact is attempted with all students identified as being at-risk of disengaging. A managed team of discipline-experienced and trained later year students employed as Student Success Advisors (SSAs) makes the outbound contact by telephone. Role statements have been developed and training and ongoing support provided for the SSAs. SSA conversations are guided by scripts tailored for each call “list”Footnote 4 and access to a range of cohort- and discipline-specific resources. Successful contact is defined as a two-way conversation and these students are classified as “at-risk contacted” (AR-C). Importantly, all call attempts are followed by an email either summarising the call discussion and setting out an action plan or, if personal contact was unsuccessful—this group classified as “at-risk not contacted” (AR-NC)—providing a series of just-in-time tailored study hints and tips. When at-risk students require specialist support, the advisors refer them on (e.g. to library staff) or in some cases, manage the referral process with the student’s permission (e.g. to a Counsellor).

Evidence from the pilot study

The Nelson et al. (2009) study reported that during Semester 1 2008 (S1/08), the SSP monitored 1,524 students in five first year units in one faculty at QUT. Of these, 608 were classified as “at risk” based on the criterion that they did not submit or failed their first assignment. Three hundred and twenty-seven of these were successfully contacted by phone (AR-C) while the remaining 281 (AR-NC) were not. There were 916 students who were classified as not at risk. As indicated above, the AR-C group received support, advice and/or referral from the SSAs while the AR-NC group received a generic email.

The outcomesFootnote 5 of the intervention were that, in three of the five units,

-

the AR-C groups persisted at almost twice the rate of the AR-NC groups; and

-

the AR-C groups achieved significantly higher final grades than the AR-NC groups.

This report presents data accumulated since that pilot study.

Expansion of the SSP

Implementing the SSP throughout QUT

In critiquing their original study, the authors noted that “the most obvious limitation… is its restriction to one faculty and consequently, the most obvious extension… is to move beyond that faculty” (Nelson et al. 2009, p. 11). Since the S1/08 pilot, there has been a planned and negotiated extension into mainly large core first year units in all of the faculties at QUT—S2/08: 8 units in five faculties, and S1–2/09: 9 units in seven (all) faculties, representing the monitoring of 10,706 students. Of these, 1,848 (17.3%) were classified as at-risk based on a variety of criteria and 945 (51.1% of those at-risk) were successfully contacted.

As in the original study,

-

Persistence was defined by comparing the number of students in the AR-C and AR-NC groups who completed the final assessment with the number of students initially classified into each group, expressed as a percentage. The Chi Square Test was used to investigate the comparison with Ǿ used as a measure of effect size; and

-

Achievement was defined as the final grade (1–7 scale) achieved at the end of the semester. The final grades of the two groups were compared using t tests with Cohen’s d used as a measure of effect size.

Results for each specific case study have restricted distributionFootnote 6 but the accumulated data is summarised in Table 1. The AR-C group persisted significantly more than the AR-NC group (89.2% vs. 66.6%) and also had a significantly higher grade (M = 4.0 [SD = 1.7] vs. 3.4 [1.8]).Footnote 7 The effect sizes indicate moderate relationships, a satisfactory outcome given the variety of units involved. These results indicate that the SSP can be implemented successfully across a variety of learning contexts and disciplines.

When the SSP was developed, although the vision was broader and included the whole transition process, the focus for its use was on the students’ “learning engagement” in the units they were enrolled in during the semester. However, since S1/09, it has been applied at other key points in the transition process. These are discussed next.

Establishing different applications of the SSP

For the aims and the vision of the SSP (see Nelson et al. 2009) to be achieved, the processes and infrastructure inherent in the SSP—proactive, engaging, task-oriented and supportive individualised contact with students by trained experienced fellow students—needed to be applied to other critical milestones in the transition process. Leveraging the FYE Policy, which states that for QUT “successful transition of our students is everybody’s responsibility” (http://www.mopp.qut.edu.au/C/C_06_02.jsp), a series of partnerships were negotiated with professional and academic staff in divisions and faculties responsible for the provision and management of administrative, academic, social and personal services for students. The result was the development of four SSP “campaigns”:

Campaign 1:

Pre-semester. Students who delay in accepting QUT’s offer of a place (and have not accepted elsewhere) or do accept but do not enrol correctly or in a timely manner. These students are contacted to raise awareness about the services available, to support enrolment activities and where appropriate to emphasise the support for students whose decision making may be complicated by financial, academic, cultural or social disadvantage;

Campaign 2:

Weeks 1–4. Welcome calls to members of cohorts with the propensity for being at-risk to “level the playing field” (e.g. rural, and Low SES students) or to those who do not attend required and/or faculty-based Orientation activities. These students are contacted to ensure that they have settled in and are aware of the services that are available to assist them and to advise them where they can collect materials and information they missed at Orientation;

Campaign 3:

During semester. Aims to improve learning engagement, as discussed above; and

Campaign 4:

End of semester. Students potentially at-risk of an administrative status leading to exclusion as a result of unsatisfactory academic performance (UAP) (http://www.mopp.qut.edu.au/E/E_06_07.jsp). The aim of this campaign is to reduce the number of students who have that UAP status and here students are made aware of their options, the importance of seeking advice and who to contact.

Taken collectively, these four successive campaigns tap into significant aspects of the life cycle of students at key points through their first year.

Although Campaign 1—where the “at-risk” behavior is the non-acceptance of offer or incorrect enrolment (labeled “NAO” for convenience)—is relatively new, there is data available from the 2010 and 2011 intakes. The accumulated data of those students showing a comparison of the enrolment behavior of the AR-C and AR-NC groups is summarized in Table 2. There is no relationship between whether students were contacted or not and their subsequent enrolment (Chi square = 0.41, df = 1, ns).

Perhaps the expectation of a significant impact of the NAO criterion on subsequent enrolment behaviour was unrealistic and the initial contact with students should be seen more as an earlier version of the “Welcome Call” currently allocated to Campaign 2. Given that the objectives of Campaign 1 are about providing information and reassurance for decision-making, it is perhaps of interest that the qualitative feedback available from the SSAs was that those students who were contacted appreciated the advice provided as it assisted in their decision-making.

The nature of Campaign 2 is such that essentially descriptive data is collected. A typical pattern of student responses to the calls is reflected in a sample of 514 students who were contacted at the beginning of Semester 1 2010 as they had missed the Orientation activities. Eighty-five percent (437) indicated appreciation for the call and the information provided. Campaign 3 has been operating since 2008 and consequently has several years of data allowing analysis of the impact of the intervention over time. This is also possible to a limited extent with information gathered during Campaign 4 which began in mid-2009. The impact of the SSP interventions in their variety of forms on the subsequent behaviour of students is the focus of the next section.

Impact of the SSP on student progression

Campaign 3: learning engagement

The data presented earlier shows that there is a significant positive impact on student persistence and success. But is this impact sustainable through to later years? This discussion focuses on those students in the AR-C and AR-NC groups in the three units where the SSP pilot intervention was successful in S1/08—Units 1, 2 and 4 in Nelson et al. (2009). This analysis compares the enrolment status of these students over a 1 year period from the end of S1/08 with their status at the end of S1/09. Only those students who were enrolled at the end of S1/08 were included in the analysis. Progression was defined by the enrolment status—enrolled or not enrolled—at the end of S1/09. The outcome of the analysis is summarised in Table 3.Footnote 8

Over three-quarters of those students who were contacted by phone in 2008 (76.9% [186/242]) progressed successfully to 2009 compared to well under one-half (45.8% [104/227]) of those who were not contacted by phone (Chi square = 47.8, df = 1, p < .001, Ǿ = 0.3). The effect size indicates a moderate relationship which is more than adequate given the longitudinal nature of the analysis. To complement this quantitative data, systematic samples of students classified as AR-C in S1/08 who were still enrolled at the end of S1/09 were telephoned during week 7 of S2/09 and asked to discuss their recollection of the telephone call/s they received and the impact of that call on their subsequent learning behaviour and progress. Eighty-five students were called and contact made with 56, a call success rate of 66%.

Indicative examples of students’ perceptions about being contacted provide insights into the immediate, medium and longer term impact of the intervention.

Immediate impact:

I sought out a mentor and the contact was of benefit.

I discovered online tutoring.

I never knew the support processes at QUT generally and in the faculty specifically existed.

I visited the Duty Tutors and went to PASS sessions for extra help.

I went to additional study sessions put on by tutors.

Medium-term impact:

The assistance helped me pass. … I wouldn’t have done as well in the subject without the extra help.

The contact had a positive effect on my studies. I don’t know how I would have gone if I hadn’t been contacted.

Longer-term impact;

I sought help from Duty Tutors in semester 2 (2008).Footnote 9

I am getting extra support in my units this year (2009) too.

I intend to seek out help this semester (S2/09).

Finally, there was almost universal appreciation that the contact was made:

I appreciated the interest.

It was good to get the call.

It was nice to know people were interested.

In summary, the qualitative data complements the quantitative dataFootnote 10: While the latter provides strong statistical support for the possibility of a sustained impact of the SSP intervention over a 12 month period, the former provides evidence of the immediate, medium and longer term impact of the program. There is no way of course to conclude categorically that a causal relationship exists between the sustained influence of the SSP intervention and the enrolment status or progression of students but the evidence—both qualitative and quantitative—is somewhat compelling.

Campaign 4: unsatisfactory academic performance

Students who are classified as at riskFootnote 11 of entering the exclusion process are identified through QUT’s end-of-semester academic performance reporting processes. First year students with poor academic performance fall into one of two categories. They may be “at-risk” if they have attempted 4 units or less and have a failing GPA (<4.0). This normally comes into effect after Semester 1. Or, at a more advanced stage of the exclusion process, they may be placed “on-probation” which has more complex criteria and normally only arises after the equivalent of one year. Only the “at risk” group is considered here. The SSP intervention aims, by the end of the following semester, to assist students to get off the “at risk” list by them attaining a GPA ≥4.0 and to still have them enrolled. The impact of the SSP on students who were classified as “at risk” at the end of S1/09 and contacted as part of Campaign 4 is discussed here by investigating these two attributes—GPA and enrolment status—at the end of S2/09.

Eight hundred and sixty-three students were classified as “at-risk” at the end of S1/09. Four hundred and eighty-three (56%) were able to be contacted at the end of S1/09. The GPA (≥4.0 or not) and enrolment status (enrolled or not) at the end of S2/09 for the contacted and not contacted groups are summarised in Table 4.

Of the 483 students contacted at the end of S1/09, 135 (28%) had a GPA ≥4.0 at the end of S2/09, while, of the 380 not able to be contacted at the end of S1/09, only 66 (17.4%) had a GPA ≥ 4.0 at the end of S2/09 (Chi square = 13.3, df = 1, p < .001, Ǿ = 0.1). In other words, contacted students had nearly twice the chance of being removed from the “at-risk” list than non-contacted students.

Of the 483 students contacted at the end of S1/09, 360 (74.5%) were still enrolled at the end of S2/09 while of the 380 not able to be contacted, only 243 (63.0%) were still enrolled (Chi square = 11.3, df = 1, p < .001, Ǿ = 0.1). In other words, contacted students had a significantly greater chance of progressing to the end of S2/09. The weak association indicated by the effect sizes for both attributes is still acceptable again given the longitudinal nature of the design and the omnibus nature of the GPA criterion.

In sum, the SSP had a positive impact on students classified as “at risk” in QUT’s exclusion process by increasing the likelihood of moving them off the “at risk” list and keeping them enrolled at QUT.

Discussion about the impact of the SSP

Summary of outcomes

This report has presented two additional sets of evidence on the impact of the SSP on at-risk students in their first year of tertiary study at a large metropolitan university in Australia. There are two significant outcomes: First, that the SSP was successfully applied in a variety of faculty-based learning contexts and disciplines, and robust enough to be applied to almost all other significant events in the academic life cycle of the first year student. And second, that there are strong indications that the impact of the intervention may be sustainable for at least 12 months and may significantly and positively influence the achievement and enrolment status of students exhibiting UAP.Footnote 12 The impact of these outcomes is explored below by examining a range of internal and external indicators.

Indicators of impact

Impact on QUT stakeholders

Qualitative comments show that various stakeholders are supportive of the SSP. For example:

From students:

Thank you so much for the tips. You brought up some good ideas and I’m sure they will help a lot. I’m definitely going to try to stick by a regular study pattern. I’m settling in well into [unit name]. Thanks for asking [Unsolicited email].

From SSAs:

The impact the SSP has had on students has been incredible. Our in-curriculum monitoring has helped students to settle into university life and let them feel that they have a university who really wants to see them succeed. The feedback I have personally received from students indicates that we offer a vital service which builds student confidence, knowledge of, and capabilities at university [Interview].

From academic staff:

It is my firm belief that the inclusion of the SSP in my unit has directly contributed to a significant improvement in the retention of students in this first year cohort. Moreover, the SSP has enhanced my capacity as unit coordinator by providing the necessary resources and strategies to maximise student retention and engagement [First Year Unit Coordinator].

From professional staff:

I believe that contacting students as part of the SSP has been constructive. Helpful information has been provided to these students and in many instances students have taken action to prevent further failure. Students have been made aware of the support services available to them and in some instances students have taken advantage of these services [Counsellor].

Impact on undergraduate attrition

One of QUT’s key aims is to reduce commencing undergraduate attrition (QUT 2008) and recent corporate data indicates a downward trend. We contend that the SSP in conjunction with the other key strategies of the FYEP (Kift et al. 2010) is positively influencing student retention. During 2004–2007, the rate of attrition oscillated but showed little overall variation. However, data for 2008 and 2009 which includes the cohorts participating in the SSP indicates the commencing undergraduate attrition rate is in decline (see Table 5).

Independent evaluation of the SSP

Boyle and Lee (2010) were commissioned by QUT to carry out an external evaluation of the TIP (Nelson et al. in press) of which the SSP was a part. They concluded that “significant reductions in student attrition in first year is one of the standout results…. [This is] clear evidence of the merit of the Student Success Project… [and] is one of the most valuable concrete impacts of TIP… If students are continuing to study rather than discontinuing it is reasonable to believe that the quality of the student learning experience is being enhanced” (pp. 3, 15, 28).

Performance in external surveys

In 2009, first year students from QUT along with other first year students in a sample of other universities around Australasia completed the Australasian Survey of Student Engagement (AUSSE) (ACER 2009) which is administered annually and the First Year Experience Questionnaire (FYEQ) (James et al. 2010) which is administered every 5 years. Data derived from the 2009 AUSSE and FYEQ both show that QUT students, compared to the national average, are less likely to intend to leave their institution or withdraw from units. The FYEQ data also shows that the intention not to leave is stronger in 2009 than in 2004, and the AUSSE data confirms the intention not to leave was stronger in 2009 than in 2008, indicating further improvement. Finally, 93% of first year students would attend QUT given the choice to start over again; and 86% of first year students rate their entire educational experience at QUT as good or excellent.

Limitations and generalisability

The SSP is still a relatively immature initiative. Yet even at this stage of its evolution, the SSP has been able to demonstrate a significant impact at all stages of the student life cycle except for Campaign 1 which may have a latent impact not yet analysed. Nevertheless, this report is based on a large pool of data, the number of QUT students and stakeholders involved is growing, interest in the program from other universities is increasing, and the information presented provides previously unreported details about a program designed to monitor and intervene with at risk students that is having a positive impact on student outcomes. Program maturity will provide opportunities for each campaign to develop clearer objectives and more sophisticated analysis and discussion of the data.

The SSP is designed to support students enrolled in an Australian university. Institutional characteristics such as multi-campus, commuter university (compared with residential college), 3 and 4 year undergraduate programs, a high percentage (approx. 40%) first in family students, a focus on discipline-specific curriculum from first year; and sector characteristics including a mass higher education sector, performance-linked government funding, growth targets for specific groups and degree attainment in the population indicate that the lessons learnt from this program may be transferrable to other institutions and environments with similar higher education systems, notably New Zealand, the United Kingdom and Canada.

Conclusion

The SSP has the following features. It is:

-

proactive, engaging, task-oriented and provides supportive individualized contact with students by trained and experienced fellow students;

-

embedded institution-wide at QUT;

-

sustainable both financially and in terms of the human resources necessary to run it;

-

supported by a sophisticated CMS that is integrated with the corporate systems at QUT;

-

robust enough to be successful in a variety of learning environments and disciplines and the complete range of student enrolment situations; and

-

potentially applicable to all undergraduate years and to postgraduate programs.

Based on these features and the considerable qualitative and quantitative evidence offered here, it seems reasonable to assume that the SSP is effective as an intervention designed to identify and support students at-risk of disengaging from their learning or their institution. It also seems reasonable to assume that, again because of the evidence and the features above, it represents good practice in the area of monitoring student engagement.

A crucial point to make here however, is that the SSP is only one element—albeit a crucial and significant one—of the FYEP at QUT. The FYEP is a curriculum focused integrated suite of research-led, evidence-based policies, principles, and associated practices (Kift et al. 2010). In the parlance of the burgeoning FYE literature, the FYEP and hence the SSP is an example of “transition pedagogy” (Kift et al. 2010) in action. Transition pedagogy is based on students’ engagement in learning, facilitated by academic-professional partnerships and shared understandings of cross-institutional processes, is institution-wide and has been rigorously evaluated and shown to have a positive impact on student success and retention. While the SSP could well be claimed as an example of good practice, it may only function effectively within such an environment.

Notes

The original name was the Student Success Project when it was part of the Transitions In Project (TIP) (Nelson et al. in press). At the completion of TIP in 2009, it was continued as an integral element of the First Year Experience Program with a slight name change to “Program” to reflect its ongoing nature. However, for convenience, the acronym SSP will be used to represent both the “Project” and the “Program” and in general discussion, “project” and “program” will be used interchangeably.

This is the QUT term for a semester-long teaching activity, variously called “subject” or “course” in other institutions. A unit normally has a 12 credit point (CP) rating.

Such as students with educational, cultural or financial disadvantage or who are members of social groups currently under-represented in higher education.

The list of students deemed to be “at risk” in a specific unit based on a particular criterion such as not submitting or failing an assessment.

Nelson et al. (2009) report outcomes for each of the five units. For brevity, they are presented here in a more concise form.

Conditions for involvement in the SSP are negotiated with unit coordinators and include confidentiality. The specific outcomes for a particular unit are only available to the unit coordinator and, with their permission, to their superiors.

A legitimate question that could be asked is whether the AR-C and AR-NC groups had fundamentally different profiles which may have predisposed them to exhibiting the identified persistence and achievement behaviours irrespective of the intervention. Data were available on gender and international, rural and English language status and two sets of profile comparisons were made—AR-C versus AR-NC and At risk (AR-C + AR-NC) versus Not at risk. Based on statistical significance and effect size data, there were no meaningful differences between the profiles of either set of groups for any characteristic.

Only persistence was investigated. The only index available for achievement was Grade Point Average (GPA) and this was regarded as too broad, its omnibus nature summarizing achievement across a wide range of units not involved in the SSP intervention.

Emphasis and year added to show longer-term impact.

Although the vast majority of comments were positive, there were some of a neutral or negative nature. For example: I can’t remember the call; I don’t think the call had any effect. I was doing OK.

There is an unfortunate overlap of use of the term “at risk” between the SSP where the term indicates that a student has not satisfied a specific criterion such as passing an assessment, and QUT administrative processes where being classified as “at risk” is determined by a combination of the student’s GPA and number of units attempted.

We also contend that the program is likely to be financially viable. While a cost-benefit analysis of the SSP is beyond the scope of this report, the authors have undertaken a relatively small study (Marrington et al. 2010) which would seem to indicate that the SSP is fiscally effective. This tentative conclusion requires further more large scale and robust testing, one of the foci of our future work in student engagement.

References

Adams, T., Banks, M., Davis, D., & Dickson, J. (2010). The Hobsons retention project. Melbourne, Australia: Tony Adams and Associates.

Australian Council for Educational Research. (2009). Engaging students for success. Australasian student engagement report. Australasian Survey of Student Engagement. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Boyle, B., & Lee, A. (2010). The teaching and learning commissioned projects 2007–2009. A strategic initiative of Queensland University of Technology. Final report of the external evaluation 2009. A report prepared for the Real World Learning Project Steering Committee, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia.

Bradley, D., Noonan, P., Nugent, H., & Scales, B. (2008). Review of Australian higher education. Final report. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia. Available at http://www.deewr.gov.au/HigherEducation/Review/Pages/ReviewofAustralianHigherEducationFinalReport.aspx.

Carlson, G., & Holland, M. (2009). AUT University FYE programme. A systematic, intervention and monitoring programme. 12th Pacific Rim first year in higher education conference. Townsville, Australia. Retrieved May 21, 2010 from http://www.fyhe.com.au/past_papers/papers09/content/pdf/14D.pdf.

Coley, C., & Coley, T. (2010). Retention and student success. Staying on track with early intervention strategies. Malvern, PA: SunGard Higher Education.

Crosling, G., Heagney, M., & Thomas, L. (2009). Improving student retention in higher education: Improving teaching and learning. Australian Universities’ Review, 51(2), 9–18.

Duncan, M., & Nelson K. J. (2008). The student success project: Helping students at risk of failing or withdrawing from a unit—a work in progress. Paper presented at the 11th Pacific Rim first year in higher education conference. Hobart, Australia. Available at http://www.fyhe.qut.edu.au/past_papers/papers08/FYHE2008/content/html/sessions.html.

Gillard, J. (2010). Address to the universities Australia annual higher education conference. Retrieved May 28, 2010 from http://www.deewr.gov.au/Ministers/Gillard/Media/Speeches/Pages/Article_100303_102842.aspx.

James, R., Krause, K.-L., & Jennings, C. (2010). The first year experience in Australian universities: Findings from 1994 to 2009. Melbourne, Australia: Centre for the Study of Higher Education.

Johnston, H., Quinn, D., Aziz, S. M., & Kava, C. Y. (2010). Supporting academic success: A strategy that benefits learners and teachers. How can we demonstrate this? A “Nuts and Bolts” presentation at the 13th Pacific Rim first year in higher education conference. Adelaide, Australia. Available at http://www.fyhe.com.au/past_papers/papers10/content/pdf/1F.pdf.

Kift, S. M., Nelson, K. J., & Clarke, J. (2010). Transition pedagogy: A third generation approach to FYE—A case study of policy and practice for the higher education sector. The International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education, 1(1), 1–20.

Lodge, J. (2010). The benefits of using social networks to increase student engagement—Not so obvious? Paper presented at the HERDSA 2010 international conference. Melbourne, Australia.

Marrington, A., Nelson, K. J., & Clarke, J. (2010). An economic case for systematic student monitoring and intervention in the first year in higher education. A “Nuts and Bolts” presentation at the 13th Pacific Rim first year in higher education conference. Adelaide, Australia. Available at http://www.fyhe.com.au/past_papers/papers10/content/pdf/6D.pdf.

Nelson, K. J., Duncan, M., & Clarke, J. (2009). Student success: The identification and support of first year university students at risk of attrition. Studies in Learning, Evaluation, Innovation and Development, 6(1), 1–15.

Nelson, K. J., Smith, J. E., & Clarke, J. (in press). Enhancing the transition of commencing students into university: An institution-wide approach. Higher Education Research and Development.

Potter, A., & Parkinson, A. (2010). First year at risk intervention pilot project: An intervention to support first year students experiencing early assessment failure. Paper presented at the 13th Pacific Rim first year in higher education conference. Adelaide, Australia. Available at http://www.fyhe.com.au/past_papers/papers10/content/pdf/4B.pdf.

Queensland University of Technology. (2008). QUT blueprint. Updated May 2008. Available at http://www.frp.qut.edu.au/services/planning/corpplan/documents/2008_QUT_BLUEPRINT.pdf.

Scott, G., Shah, M., Grebennikov, L., & Singh, H. (2009). Improving student retention: A University of Western Sydney case study. Journal of Institutional Research, 14(1), 9–23.

Simeoni, R. J. (2009). Student retention trends within a health foundation year and implications for orientation, engagement and retention strategies. Paper presented at the 12th Pacific Rim first year in higher education conference. Townsville, Australia.

The National Audit Office. (2007). Staying the course: The retention of students in higher education. London: The National Audit Office. Available at http://www.nao.org.uk/publications/0607/student_retention_in_higher_ed.aspx.

Tinto, V. (2009). Taking student retention seriously: Rethinking the first year of university. Paper presented at the FYE curriculum design symposium 2009, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia. Retrieved March 4, 2009, from http://www.fyecd2009.qut.edu.au/resources/SPE_VincentTinto_5Feb09.pdf.

Wilson, K., & Lizzio, A. (2008). A ‘just in time intervention’ to support the academic efficacy of at-risk first-year students. Paper presented at the 11th Pacific Rim first year in higher education conference. Hobart, Australia.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the work of Tracy Creagh who carried out the student interviews and the initial collation of the interview data and Wayne Duxbury who implemented and maintains the CMS which supports the SSP’s operations and facilitates this detailed level of reporting.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nelson, K.J., Quinn, C., Marrington, A. et al. Good practice for enhancing the engagement and success of commencing students. High Educ 63, 83–96 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9426-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9426-y