Abstract

Rationale

The long-term outcome of idiopathic macrocephaly is presently unknown.

Methods and results

In the current study (n=15), MRI conducted at long-term review showed regression of orbito-frontal extradural collections and normal or slightly enlarged ventricular space compared to infant examination. Head circumference had normalised in all but one participant. Neuropsychological assessments of nine participants showed general intellectual ability within the normal range in the majority of participants; however, specific deficits in attention were evident. Clinical interviews conducted with a smaller sub-group revealed anecdotal histories of behavioural difficulties and reading or arithmetic difficulties in half of the total sample.

Conclusions

Prospective review studies such as this indicate that abnormal radiological findings in infancy are not necessarily predictive of neurodevelopmental problems and may reflect a normal variant. However, while overall intellectual ability may be within average limits in this diagnostic sample, considerable individual variations remain in specific areas of neuropsychological function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Idiopathic macrocephaly is thought to occur as a benign condition during infancy in the absence of other neurological dysfunctions [1, 2]. Often diagnosed within the first year of life, the condition of idiopathic macrocephaly typically describes a head circumference >95th centile [1], with characteristic radiological features of orbito-frontal extradural collections and normal or slightly enlarged ventricular space [3, 4]. While extradural collections often resolve in the short-term [2, 3, 5, 6], there are conflicting reports that clinical and radiological abnormalities will persist [7–9]. Further, there are inconsistent reports of normalisation (i.e. <95th centile) of enlarged head circumference over time [1, 10–11]. Indeed, reports of adult macrocephaly cases with normal neurologic findings, such as the parents of macrocephalic children, may lend further support for the persistency of macrocephaly throughout life [1, 12, 13]. In addition, the developmental prognosis of idiopathic macrocephaly in childhood is inconsistent in the nomenclature [5, 14, 15,]. Specifically, one study [15] reported on the developmental progress of nine infants with enlarged subarachnoid spaces as identified by Computed Tomography (CT) scan. Participants were prospectively followed to 2 and 3 years of age. All participants showed normal or only minimally increased ventricular size and none developed hydrocephalus at follow up. Seven of the nine infants reported showed a ‘characteristic pattern’ of delayed gross motor development during the first year, although at follow up the same seven participants showed age-appropriate motor development. However, three participants were noted to have developed speech and language delay at review. While the follow up duration in this study was too short to determine the prognostic implications, speech and language delay remains a risk factor for ongoing language and academic difficulty during school age [16]. Another study [9] reported that, in their group of 20 school age children (aged 6–15 years), idiopathic macrocephaly was a clinical entity associated with subtle motor problems and neurodevelopmental dysfunction. Further, there are mixed findings regarding the intellectual functioning of children with macrocephaly [7, 17–21], in addition to reports of more specific cognitive deficits such as arithmetic problems, visuo-motor difficulty and reduced verbal fluency [9, 22].

While previous studies report a benign outcome in the first few years of life for patients with idiopathic macrocephaly, the long-term prognosis (i.e. beyond childhood years) remains speculative. To date, there are few long-term outcome studies that have investigated idiopathic macrocephaly in infancy using Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and also include detailed cognitive assessment. As such, the current study aims to extend previous research by investigating the natural long-term course of the condition by providing information on the neuroradiological, neurodevelopmental and neuropsychological features of a group of infants diagnosed with idiopathic macrocephaly and managed conservatively.

Materials and methods

Between 1985 and 1986, a total of 41 infants (11 girls, 30 boys) were recruited at the Royal Alexandra Hospital for Children, Sydney, Australia, to participate in a study investigating the radiological and neurological sequelae of macrocephaly. Macrocephaly was defined at initial presentation as an occipito-facial head circumference (OFC) greater than the 95th centile on standard United States child growth charts [23–25]. Infants were initially referred to the hospital for the evaluation of macrocephaly or a rapidly growing head circumference from family health clinics after the chance finding of macrocephaly during routine or unrelated visits. Infants were recruited to the study if they fulfilled the criteria for macrocephaly.

At first presentation to the family health services, all 41 participants (mean age of 8 months with a range from 3–30 months) underwent standard neurological investigation. Head circumference, past medical history, family history and other medical problems were recorded for all participants. After a mean duration of 27 months (range of 4–64 months), all participants aged from 9 to 87 months (mean age of 3 years) received CT (head) or MRI (head) examinations and standard neurological examinations. Measurements of head circumference using a standard tape measure were also conducted. The results of these examinations were noted in clinical records. One participant went on to receive a ventriculoperitoneal shunt following initial presentation.

For the current study, exhaustive attempts were made to follow up all of the 41 participants from hospital records who had earlier satisfied the condition of idiopathic macrocephaly. Ethical clearance to conduct the study and contact potential participants was granted by the hospital and university ethics committees. From the original group (n=41), 9 participants (2 girls, 7 boys) consented to review assessments; 6 participants who were contacted refused to undergo formal assessments, although they consented to clinical interviews only, and 22 participants were unable to be located through hospital records. The remaining four participants were excluded from the current review as there was evidence of potential co-morbidities or non-conservative treatment approaches for macrocephaly (i.e. co-existing developmental disorder or central nervous system (CNS) malformation, hydrocephalus, or insertion of ventriculoperitoneal shunt in infancy). The total of 15 participants had a mean age of 18 years (range from 17–20 years). An average of 15 years had elapsed since the initial examinations. In the current review, using a counter-balanced administration, all patients again underwent neuropsychological assessments, MRIs (head) and standard neurological examinations. The OFC of each patient was measured by the neurosurgeon over the greatest supra orbital and occipital prominences using a non-stretch tape measure. The respective weight and standing height of each patient was measured in accordance with standardised procedures. OFC was compared with standardised growth charts for adults [26]. The standard neurological examination comprised an assessment of all cranial nerves and primitive reflexes. MRI was performed by an independent neurosurgeon who was blind to the participants’ developmental history and cognitive test results. MRI was performed using a Philips Gyroscan ACS-N.T. Shortbore 1.5 T magnet with release 6 software. A gradient of 23 mT/m using a quadrature head coil recorded T1 axial slices of the brain. The MRI images of all patients were evaluated for enlargement of the subarachnoid space and dilatation of ventricular size.

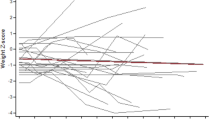

Additionally, at review all participants completed a neuropsychological assessment during one half-day session administered by a neuropsychologist. The cognitive domains of intellectual ability, attention, executive function, visuo-spatial function, memory and emotional status were investigated using standardised neuropsychological tests. The test protocol comprised the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Adults—Revised (WAIS-R: short form) [27]Footnote 1, the Rey-Osterreith Complex Figure (ROCF) [28], Conner’s Continual Performance Test (CPT) [29], the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) [30], the Wechsler Memory Scale—Revised (WMS-R: selected sub-tests) [31], the Booklet Category Test (BCT) [32], the Trail Making Test (TMT A and TMT B) [33], the Crawford Excluded Letter Fluency Test (personal communication from Shores E. A. with permission) and the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) [34]. Given the small number of this study sample, parametric statistical analysis on neuropsychological data was not appropriate. All test scores were converted to z scores to allow for comparison between participants and within specific tests (Table 1).

In an attempt to gather additional information, 15-minute telephone interviews were conducted with one parent of each participant. The interview comprised a standard format investigating academic attainments, as well as the behavioural and social development of their child.

Observations and results

Neuroradiological findings

A retrospective review of the medical records for the nine participants revealed enlarged subarachnoid spaces in all participants and enlarged ventricular sizes in two participants. Percentiles for OFC measurement increased between initial presentation and infant follow up in all participants (Table 2). None of the nine participants manifested symptoms of increased intracranial pressure following initial presentation at the health clinic.

At long-term review, all participants who underwent radiological examinations had normalised subarachnoid spaces and ventricular sizes when compared to their earlier medical history. A typical radiological finding at long-term review showed the resolution of the widened subarachnoid space on MRI as judged by the treating neurosurgeon. All cases presented as normal on standard neurological examination initially and long-term review. All cases except one presented with ‘normalised’ OFC relative to adult growth charts and were proportionate to their height measurements for either boys or girls.

Neurodevelopmental characteristics

Table 3 shows the developmental characteristics of the 15 participants. Regarding developmental history, two participants (cases 10 and 14) who presented with abnormal motor development at initial presentation were noted to have normal motor development at first follow up, while two other participants (cases 2 and 4) who were considered to have normal motor development at initial presentation, were found to have motor delay at first follow up. Another two participants (cases 6 and 8) had developed speech delay by first follow up.

The results of the clinical interviews revealed that half of the total sample at review reported a history of reading or arithmetic difficulty during schooling. Of the six participants who refused to undergo formal assessment, four had had shunts inserted at some time in early infancy. This was due in all four cases to the development of intracranial pressure and a probable hydrocephalic picture.

Neuropsychological assessment

WAIS-R sub-test results indicated that for six out of nine participants, intellectual ability was estimated to be within the average range [35]. Intellectual ability was within the low-average to borderline range for the remaining three participants.

On tests of new learning and memory, seven out of nine participants scored within average limits compared to age-related norms on measures of immediate memory (i.e. RAVLT Total 1-V, WMS-R Logical Memory I, Figural Memory) (see Table 1) and delayed memory (RAVLT Delay Recall, RAVLT Recognition, Logical Memory II). Two participants (cases 2 and 8) consistently fell below the average range on the RAVLT. While most participants scored within average limits on tests of attention [TMT B, Digit Span (WAIS-R), Digit Symbol (WAIS-R)], four participants performed at a below-average level on the TMT A. On a computer-generated test of attention (CPT), three participants were identified as having attention problems overall. More specifically, six participants showed an unusually high rate of omission and/or commission errors and four showed poor perceptual sensitivity. On tests used to measure executive function, all nine participants fell within the average range for age on the measures of BCT and ROCF. On a test of letter fluency, one participant scored below average limits for age and education (<2 standard deviations from the mean). Results from the DASS indicated that one participant from nine showed elevated levels on the depression sub-scale.

Discussion

The current study aimed to identify the long-term neuroradiological, neurodevelopmental and neuropsychological outcome of infants diagnosed with idiopathic macrocephaly who were managed conservatively. Previous research into this condition has reported contradictory findings in the short-term and the long-term prognosis has not been well understood. In addition, the cognitive development of children with idiopathic macrocephaly has been underreported, and thus, the ongoing course of the condition has been speculative. A previous study [6] has suggested that abnormalities seen on CT scan and the normalisation of head circumference may well resolve within 18–24 months. However, other studies of macrocephalic patients suggest that clinical and radiologic abnormalities will be present in the long-term [8,9]. The MRI results of the current study support findings that extradural collections, which may indicate an enlarged subarachnoid space, will regress over time and may indeed ‘normalise’ in the absence of other pathological processes [6]. This finding has important implications in the early neurosurgical management of this diagnostic group.

The widening of the subarachnoid space in children may indeed be a variation in the normal development process of the brain whereby there is a transient accumulation of CSF in the frontoparietal region [11]. Children with rapidly increasing head sizes may therefore have an exaggeration of this widening. Subarachnoid widening in the infant may also indicate a non-specific neurodevelopmental occurrence and is potentially more common than previously thought [5].

Despite previous evidence of reduction in the enlarged subarachnoid space at as early as 7-month follow up, most studies report a persistence of enlarged head circumference in the short-term [1, 7, 8, 10]. Given these findings, an enlarged head circumference may persist beyond childhood and into adult years, as in the cases of parents with enlarged head circumferences [12, 13]. However, the majority of the current sample presented with head circumferences within the normal range for adults, which supports the suggestion that idiopathic macrocephaly as a constellation of symptoms may be considered a normal variant. Evidence of prolonged macrocephaly at long-term review was noted in only one participant who presented with a larger OFC relative to height and gender. MRI findings of normalised subarachnoid space in this overall sample suggest that the brain appears to have ‘grown into’ the cranial vault over time, thereby minimising the larger subarachnoid space.

Previous studies found that early motor delay resolved over time in infants with idiopathic macrocephaly [5, 14, 15]. Although two cases in the current sample presented with normal motor development during early childhood despite indications of motor delay at first neurological examination, two other cases appeared to develop motor delay within the same timeframes. Two additional cases in the current sample were noted to have developed speech problems by early childhood follow up and subsequently performed at below-average levels across most neuropsychological tests at long-term review. Given the limited numbers in the current sample, findings regarding motor delay remain inconclusive. However, no long-term gross motor impairments were noted in the neurological examination for any of the participants in this study.

Despite abnormal radiological findings at early examination, the results of neuropsychological assessment suggest that the overall intellectual ability for the majority of the current sample was within the normal range on standardised measures at long-term review. This is consistent with a previous study [18] that reported that the overall intellectual ability of children diagnosed with idiopathic macrocephaly remained within the average range. Additionally, the majority of participants performed within average limits on tests of memory and executive functioning. However, the results of verbal fluency in the current sample did not support previous research findings of deficits in naming fluency [9].

Although there was no clear pattern of cognitive deficit or strength across neuropsychological tests for the sample, a greater number of participants experienced difficulty in some specific areas of cognitive functioning. Reduced performances were noted on two neuropsychological tests associated with attention (TMT A, CPT). The TMT A is considered a test of attention speed, sequencing and visuo-motor scanning [36], while the CPT aims to measure sustained attention skills. The reduced scores on the TMT A are consistent with previous research that indicated reduced upper-limb speed and visuo-motor control in a sample of school-aged children with idiopathic macrocephaly [9]. It could be speculated that reduced visuo-motor skills in the current sample group contributed to reduced scores on the TMT A. Further, results from the CPT measure revealed six out of nine participants made an unusually high proportion of commission/omission errors and a total of four participants showed reduced perceptual sensitivity. On this particular test, commission/omission errors indicate impulsive responding, whereas low perceptual sensitivity refers to reduced attention to detail. The neuropsychological literature purports that attention skills are considered to be a function of the frontal lobes [30]. Thus, the question is raised over what impact, if any, the enlargement of subarachnoid space in the frontal convexities during childhood may have on the development of frontal lobe functions and the subsequent acquisition of specific attention skills. This new finding of reduced attention skills in a high proportion of participants appears to conflict with the current ‘normalised’ radiological results and casts some doubt over the understanding that idiopathic macrocephaly is a benign prognostic entity.

The data presented highlight the substantial variability between participants in this sample. Despite normal neuroradiological investigation at second follow up, two individuals (cases 2 and 8) consistently scored below the average limits (>2 standard deviations below the mean) across a range of cognitive domains of attention, immediate memory and delayed memory. Developmental and academic history gathered from clinical interviews revealed a background of special reading tuition in the same two participants. This finding is supported by previous research [7] where there was evidence of ongoing cognitive and language difficulty following developmental delay at short-term follow up. Additionally, reading or arithmetic difficulty was a common finding within the clinical interview data. This result highlights the potential value of monitoring academic performance in these areas.

The current sample size was a limitation in this study in that it was not large enough to generate quantitative comparison. However, the results from neuropsychological assessments highlight potential areas of weakness, particularly in visuo-motor skills and attention. It is important to note that the current sample may be somewhat biased in that those that agreed to formal neuropsychological assessment may be unrepresentative of the original group of infants diagnosed with macrocephaly (n=41).

In conclusion, neuroradiologic and neuropsychological review has demonstrated that abnormal radiological investigation of idiopathic macrocephaly of infancy does not necessarily lead to abnormal radiological outcome and, importantly, impaired neuropsychological functioning. All participants in the current study presented with ‘normalised’ MRI examination at long-term review. However, while the majority of participants performed at an average level of general intellectual ability, comprehensive neuropsychological assessment identified a sub-group of children who showed more specific cognitive difficulties. Given these findings, early investigation of cognitive function, with particular emphasis on attention and visuo-motor skills, with monitoring of behavioural and academic performance may be warranted in infants diagnosed with idiopathic macrocephaly. In addition, the late onset hydrocephalic symptoms as noted in some patients support the need for continued clinical review. A prospective study involving comprehensive periodic assessment of a larger number of infants diagnosed with idiopathic macrocephaly, especially through school years, would be useful in determining the need for future intervention.

Notes

The WAIS-R short form utilised for this study has a validity coefficient of .94, comprising subtests of Picture Completion, Vocabulary, Digit Span, Digit Symbol, Arithmetic and Similarities.

References

Alper G, Ekinci G, Yilmax Y, Arikan C, Telyar G, Erzen F (1999) Magnetic resonance imaging characteristics of benign macrocephaly in children. J Child Neurol 14:678–682

Pettit RE, Kilroy AW, Allen JH (1980) Macrocephaly and head growth parallel to normal growth pattern: neurological, developmental, and computerized tomography findings in full-term infants. Arch Neurol 37:518–521

Bodensteiner J (2000) Benign macrocephaly: a common cause of big heads in the first year. J Child Neurol 15:630–632

Nellhaus G (1972) Benign idiopathic megalencephaly: neuroradiologic confirmation. Neuroradiology 4:128

Ment LR, Duncan CC, Geehr R (1981) Benign enlargement of the subarachnoid spaces in the infant. J Neurosurg 54:504–508

Wilms G, Vanderscheuren G, Demaerel PH, Smet MH, Van Calenbergh F, Plets C, Goffin J, Casaer P (1993) CT and MR in infants with pericerebral collections and macrocephaly: benign enlargement of the subarachnoid spaces versus subdural collections. Am J Neuroradiol 14:855–860

Gherpelli JL, Scaramuzzi V, Manreza ML, Diament AJ (1992) Follow-up study of macrocephalic children with enlargement of the subarachnoid space. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 50:156–162

Laubscher B, Deonna T, Uske A, van Melle G (1990) Primitive megalencephaly in children: natural history, medium term prognosis with special reference to external hydrocephalus. Eur J Pediatr 149:502–507

Sandler AD, Knudsen MW, Brown TT, Christian BM (1997) Neurodevelopmental dysfunction among nonreferred children with idiopathic megalencephaly. J Pediatr 131:320–324

Compen-Kong R, Landeras L (1991) The neuroevolutionary profile of the nursing infant with macrocephaly and benign enlargement of the subarachnoid space, abstract. Bol Med Hosp Infant 48:440–444

Odita JC (1992) The widened frontal subarachnoid space: a CT comparative study between macrocephalic, microcephalic, and normocephalic infants and children. Childs Nerv Syst 8:36–39

Cole TKP, Hughes HE (1991) Autosomal dominant macrocephaly: benign familial macrocephaly or a new syndrome? Am J Med Genet 41:115–124

Day RE, Shutt WH (1979) Normal children with large heads—benign familial megalencephaly. Arch Dis Child 54:512–517

Maytal J, Alvarez L, Elkin CM, Shinnar S (1987) External hydrocephalus: radiologic spectrum and differentiation from cerebral atrophy. Am J Neuroradiol 8:271–278

Nickel RE, Gallenstein JS (1987) Developmental prognosis for infants with benign enlargement of the subarachnoid spaces. Dev Med Child Neurol 29:181–186

Sattler JM (1992) Assessment of children. Maple Vail, San Diego

Appleton RE, Bushby K, Gardner-Medwin D, Welch J, Kelly PJ (1991) Head circumference and intellectual performance of patients with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Dev Med Child Neurol 33:884–890

Asch AJ, Myers GJ (1976) Benign familial macrocephaly: report of a family and review of the literature. Pediatrics 57:535–539

Gooskens RHJM, Willemse J, Faber JA, Verdonck AFMM (1989) Macrocephalies — a differentiated approach. Neuropediatrics 20:164–169

Pollack IF, Pang D, Albright L (1994) The long-term outcome in children with late-onset aqueductal stenosis resulting from benign intrinsic tectal tumours. J Neurosurg 80:681–688

Smith RD, Ashley J, Hardesty RA, Tulley R, Hewitt J (1984) Macrocephaly and minor congenital anomalies in children with learning problems. J Dev Behav Pediatr 5:231–236

Densch LW, Anderson SK, Snow JH (1990) Relationship of head circumference to measures of school performance. Clin Pediatr 29:389–392

Tanner JM (1978) Boys: birth–16 years: head circumference. Castlemead Publications, Welwyn Garden City, Herts

Tanner JM (1978) Girls: birth–16 years: head circumference. Castlemead Publications, Welwyn Garden City, Herts

Hamill PVV, Drizd TA, Johnson CL (1979) Physical growth: National Centre for Health Statistics percentiles. Am J Clin Nutr 32:607–629

Bushby KMD, Cole T, Matthews JNS, Goodship JA (1992) Centiles for adult head circumference. Arch Dis Child 67:1286–1287

Wechsler D (1981) Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—revised. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio

Meyers J, Meyers K (1995) The Meyers scoring system for the Rey Complex Figure and the recognition trial: professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa

Conners CK, Multi-Health Systems Staff (1995) Conners Continuous Performance Test. Multi-Health Systems, Toronto

Lezak MD (1995) Neuropsychological assessment, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, New York

Wechsler D (1987) Wechsler Memory Scale—revised. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio

DeFilippis NA, McCampbell E (1979) Manual for the Booklet Category Test. Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa

Reitan RM, Wolfson D (1988) The Halstead–Reitan neuropsychological test battery. Neuropsychology Press, Tucson

Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF (1995) Manual for the depression, anxiety and stress scales, 2nd edn. Psychology Foundation, Sydney

Kaufman AS (1990) Assessing adolescent and adult intelligence. Allyn and Bacon, London

Spreen O, Strauss E (eds) (1999) A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms, and commentary. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the early work of Dr. Ian Johnson and Dr. Elizabeth Fagan that lead to the preparation of the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Muenchberger, H., Assaad, N., Joy, P. et al. Idiopathic macrocephaly in the infant: long-term neurological and neuropsychological outcome. Childs Nerv Syst 22, 1242–1248 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-006-0080-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-006-0080-0