Abstract

This article provides a survey of recent normative work on justice. It shows how the concern for distributive equality has been questioned by the idea of personal responsibility and the idea that there is nothing intrinsically valuable in levelling down individual benefits. It also discusses the possibility of combining a concern for the worse off with a concern for Pareto efficiency, within both aggregative and nonaggregative frameworks, which includes a discussion of the arguments of prioritarianism, sufficientarianism, and welfarism. Finally, the article briefly reviews the modern literatures on rights-based reasoning, intergenerational justice and international justice.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Altruism

- Behavioural economics

- Choice

- Compensation

- Consequentialism

- Difference principle

- Egalitarianism

- Equality

- Equalization

- Evolutionary economics

- Fair allocation

- Fairness

- Harsanyi, J. C.

- Independence of irrelevant alternatives

- Indexing impasse

- Infinite horizons

- Intergenerational justice

- International justice

- Interpersonal utility comparisons

- Justice

- Leximin

- Libertarianism

- Maximin

- Nozick, R.

- Pareto efficiency

- Pareto indifference

- Pareto principle

- Poverty

- Poverty alleviation

- Preferences

- Primary goods

- Prioritarianism

- Rawls, J.

- Responsibility

- Self-ownership

- Sen, A.

- Social welfare function

- Sufficiency

- Sufficientarianism

- Tyranny of aggregation

- Utilitarianism

- Veil of ignorance

- Welfarism

- Well-being

JEL Classifications

Modern thinking on justice has been strongly motivated by the work of Rawls (1971, 1993). Rawls not only developed a prominent theory of justice that has been extensively analysed, he also expressed in a very powerful way the fundamental role justice has to play in the evaluation of social arrangements. Rawls argued that justice is the first virtue of social institutions, as truth is of systems of thought. ‘A theory however elegant and economical must be rejected or revised if it is untrue; likewise, laws and institutions no matter how efficient and well-arranged must be reformed or abolished if they are unjust’ (1971, p. 3).

The fundamental problem is that there are many divergent views of what constitutes a just society, and thus many divergent views of what are just social arrangements. Rawls introduced the notion of a reflective equilibrium, which, roughly speaking, is attained when our principles and judgements of justice coincide. The normative literature on justice can be seen as part of a process towards such a reflective equilibrium, where the aim is to attain a better understanding of both the consequences and the underlying foundation of various possible conceptions of justice.

Further understanding of different conceptions of justice is also important in the positive analysis of individual behaviour, because it is by now well-established that people in many situations are motivated by fairness considerations (Camerer 2003). There is a substantial literature in behavioural economics that study in more detail what kind of fairness norms motivate people and to what extent these fairness norms survive in different settings (Konow 2003), and also an important literature in evolutionary economics that aim at understanding why our concern for justice has evolved (Binmore 2005; Skyrms 1996, 2003).

This article is a sequel to Sen’s entry on justice in the first edition of The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics (reproduced in this edition), where Sen argues for a broader view of justice than what is captured by utilitarianism (see also Sen 1979). Sen views utilitarianism as the amalgam of three distinct principles, namely, welfarism, sum-ranking, and consequentialism, and he shows how each of them was contested in the early modern literature on justice. In this article, I survey how these questions have been dealt with in recent normative work on justice. In particular, I focus on the role of distributive equality. Sen argued convincingly for the need to take explicit note of inequalities in the distribution of utilities or some other equalisandum, and the standard welfare economic view is presently that justice requires a trade-off between equality of utility and the sum of utility. Interestingly, however, the concern for distributive equality has been questioned from different perspectives. First, it has been argued that distributive equality neglects the role of personal responsibility, and, second, it has been argued that distributive equality legitimizes the intrinsic value of levelling down utilities. I review each of these arguments before I move on to the classical question of how to incorporate equality or a concern for the worse off in an aggregative theory of justice. Any aggregative theory of justice, however, faces what I call the tyranny of aggregation, and therefore, inspired by Rawls (1971), there have been many attempts to establish a non-aggregative framework that combines a concern for equality with a concern for Pareto efficiency. I discuss some of the most prominent non-aggregative perspectives and also some recent developments on rights-based non-consequentialistic reasoning. Finally, I review briefly the growing literature on intergenerational and international justice, which raises interesting questions on how to deal with individuals who are in asymmetric relationships to each other.

Distributive Equality and Personal Responsibility

Modern egalitarian theories of justice seek to combine the values of equality and personal responsibility. The contemporary focus on this relationship can be traced back to Rawls (1971), but it has historical roots both in the US Declaration of Independence (1776) and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen (1789). The American and French societies developed in rather different directions, though, and, as noted by Nagel (2002, p. 88), ‘what Rawls has done is to combine the very strong principles of social and economic equality associated with European socialism with the equally strong principles of pluralistic toleration and personal freedom associated with American liberalism, and he has done so in a theory that traces them to a common foundation’. The ideas of Rawls have been developed further, notably by Dworkin (1981), Arneson (1989), Cohen (1989), Kolm (1996), Roemer (1993, 1996, 1998), van Parijs (1995), Bossert (1995), Fleurbaey (1995a, b), Bossert and Fleurbaey (1996), and Fleurbaey and Maniquet (1996, 1999), where the main achievement has been to include considerations of personal responsibility in egalitarian reasoning. The two basic conditions put forward in this literature are the principle of equalization and the principle of responsibility. The principle of equalization states that if two persons have exercised the same level of responsibility, then justice demands that they should have the same outcome in the morally relevant space. The principle of responsibility states that inequalities due to different levels of responsibility can be justified.

A fundamental question is whether the two basic principles can be combined in a coherent theory of justice. Dworkin (1981) proposes the idea of a hypothetical insurance scheme, where each person makes her choice of insurance behind a thin veil of ignorance where everyone knows his or her own preferences and is in the possession of the same amount of resources. The equilibrium outcome in this insurance market forms then the basis for the just compensation of disadvantages in the actual world. The proposal of Dworkin has been criticized by Roemer (1985), who argues that, if individuals maximize their expected utility in the insurance market, they insure against states in which they have low marginal utility. If low marginal utility happens to be the consequence of some inborn handicaps, then the hypothetical market will tax the disabled for the benefit of the others. Hence, if we do not want to hold people responsible for their handicaps, then this approach violates the principle of equalization in the actual world, even though it satisfies it if we define responsibility in relation to the choices behind the veil of ignorance. For a further discussion of this issue, see Dworkin (2002), Fleurbaey (2002) and Roemer (2002a).

Bossert (1995) and Bossert and Fleurbaey (1996) study the compatibility of the principle of responsibility and the principle of equalization within a model where pre-tax income of each person is determined by a vector of factors and where we hold people responsible for some of these factors (for example, effort) and not for others (for example, family background). They show that, if the principle of responsibility is interpreted as saying that people should be held fully responsible for the actual consequences of changes in their behaviour, then it cannot be combined with the principle of equalization. However, such an interpretation of the principle of responsibility can be questioned because in many cases it may imply that inequalities reflect differences that we do not want to hold people responsible for, including their inborn talent (Tungodden 2005). However, there are many other possible interpretations of the principle of responsibility which can be combined with the principle of equalization (Fleurbaey and Maniquet 2008). One possibility is captured by the egalitarian equivalent mechanism, where people face a given reward scheme for their choice of effort and then share equally the deficit or surplus that follows from this scheme.

A basic insight from this literature is that, if we want to satisfy the principle of equalization, then justice requires that people should face the same consequences from the same kind of behaviour. However, this implies that there is a general tension between the just allocation and Pareto efficiency, where the latter requires that people should face the actual consequences of their behaviour. This tension is not present if one accepts a weaker version of the principle of equalization, which requires complete equalization only for some level of responsibility (Kolm 1996). Such an approach is consistent with holding people fully responsible for the actual consequences of changes in their behaviour, as illustrated by the conditional egalitarian mechanism introduced by Bossert and Fleurbaey (1996).

Another interesting insight that follows from this framework is that an income tax system may be unjust in two different ways. First, it may be unjust because it does not equalize sufficiently among people exercising the same level of responsibility. Second, it may be unjust because it equalizes too much between people exercising different levels of responsibility. Within the more standard framework of welfare economics, where considerations of responsibility are not introduced, the second type of injustice is usually overlooked.

The location of the responsibility cut is essential in any application of a responsible-sensitive egalitarian theory, which is most easily seen by noticing the implications of two extreme cases. No redistribution would be justifiable if all factors are responsibility factors, while, ideally, outcomes should be equalized completely if all factors are non-responsibility factors. If there are both responsibility factors and non-responsibility factors, however, then the ideal level of redistribution also depends on the degree of inequality in the non-responsibility factors. However, it is in general not the case that the ideal level of redistribution is lower if the differences in some non-responsibility factor are eliminated or if we move to a situation where people are held responsible for more factors. This will be the case only if there are no negative correlations between various non-responsibility factors in society (Cappelen and Tungodden 2006).

The standard way of defining the responsibility cut is to rely on the distinction between choice and circumstances, where people are held responsible for their choices but not for their circumstances (Cohen 1989). However, this approach is controversial and raises metaphysical questions about the basis for our choices (Dennet 2003). Alternatively, we may think of the responsibility cut in political terms, whereby people are assigned responsibility for a particular set of factors without relying on a particular metaphysical view of individual choices (Fleurbaey 1995a). The question of where to locate the responsibility cut then mirrors the political debate on redistribution, where right-wingers argue that people should be held responsible for a large fraction of the factors influencing their lives, whereas left-wingers hold individuals responsible for a smaller set of factors.

A further problem in applying this framework is how to obtain a more precise measure of the degree of responsibility a person has exercised. To simplify, suppose that we consider a case where only labour effort and talent affect outcome, and where we do not want to hold people responsible for their talent. Roemer (1993, 1996, 1998) proposes that we partition the population into talent groups, and then consider two individuals identical in terms of responsibility if they are at the same percentile of the labour effort distribution within their class of talent. This approach can be generalized to any number of responsibility and non-responsibility factors by studying conditional distributions more generally. Roemer combines this framework with a maximin interpretation of the principle of equalization and a utilitarian interpretation of the responsibility principle. His proposal equalizes as much as possible among people who have exercised the same level of responsibility, but rewards individuals for additional labour effort only if this maximizes the total amount of utility (or some other equalisandum) within the sub-population consisting of those who receive the lowest level of utility at each percentile of labour effort level. In sum, this provides us with a complete theory of justice, not only the ideal solution, and Roemer (2002b) illustrates how this framework may be applied in studying redistribution policies. Alternative versions of Roemer’s framework are studied in Van de gaer (1993) and Ooghe et al. (2006).

Distributive Equality and Prioritarianism

A fundamental critique of distributive equality has been launched in the debate on prioritarianism and egalitarianism (Parfit 1995; Temkin 1993, 2000; Scanlon 2000), where it has been questioned whether even in situations where people have exercised the same level of responsibility we should find distributive equality intrinsically valuable.

Scanlon (2000) argues that equality very seldom seems to be what we care about and that our concern for equality in most cases can be traced back to other fundamental values. We care about a reduction in inequality because, among other things, it contributes to the alleviation of suffering, the feeling of inferiority, and the dominance of some over the lives of others. Parfit (1995) questions the intrinsic value of equality by appealing to the levelling down objection. A reduction in inequality can take place by harming the better off in society without improving the situation of the worse off. If equality is intrinsically valuable, then this must be good in some respect. However, to harm everyone cannot be good in any respect, and hence inequality cannot be intrinsically bad.

Parfit (1995) suggests that there is an alternative view, what he calls the priority view, which better captures our concern for the worse off and avoids the levelling down objection. Parfit defines prioritarianism as the view that, the worse off people are, the more important it is to benefit them. This, however, is an imprecise statement which does not clearly set apart prioritarianism from egalitarianism, and it has been questioned in the literature whether it is at all possible to distinguish these two perspectives (Broome 2007). As pointed out by Fleurbaey (2007), a prioritarian view will always coincide with an egalitarian view that cares both for total utility (or well-being) and equality, and which measures inequality with the same index that is implicit in the prioritarian view. However, it can be argued that the two perspectives reflect different ways of justifying priority to the worse off. The prioritarian justification focuses on the absolute circumstances of the worse off, while the egalitarian justification focuses on the relative circumstances of the worse off (Tungodden 2003).

Justice, Welfarism and Aggregation

A substantial literature has studied how to combine a concern for distributive equality or the worse off with other values, in particular Pareto efficiency. This raises two core questions. First, we need to establish a metric of individual advantage and, second, we need to determine how much weight to assign to distributive equality relative to other values.

Much of this work has rested on the assumption of welfarism, which states that the social ranking of alternatives must depend only on the utility levels of individuals in these alternatives (Arrow 1951; Sen 1970a; Bossert and Weymark 2002). Welfarism may be assumed as a basic assumption or it may be derived from the more fundamental principles of Pareto indifference and independence of irrelevant alternatives (d’Aspremont and Gevers 1977). There has been a huge literature criticizing welfarism. On the one hand, it has been argued that welfarism contains an unsatisfactory representation of individual advantage. On the other hand, it has been claimed that it is impossible to apply welfarism in practice. We may label these the pragmatic and the fundamental arguments against welfarism.

The underlying idea of the pragmatic argument is that we ‘must respect the constraints of simplicity and availability of information to which any practical policy conception [of justice] is subject (Rawls 1993, p. 182). Welfarism implies that interpersonal comparisons should be based on comparisons of preference satisfaction, which in general is considered to be non-observable. Thus, the welfaristic framework does not provide a practicable public basis for considerations of justice.

The fundamental critique of welfarism is concerned with the substantive claims of this framework. Rawls (1971, 1993) argues that utility or well-being is not a relevant feature of states of affairs. Appropriate claims should refer to an idea of rational advantage that is independent of any particular comprehensive doctrine of the good, and for this purpose Rawls suggests a list of primary goods. Sen (1985, 1992a) defends the focus on well-being in social choices, but he argues against the idea of well-being implicit in welfarism. Sen introduces the framework of functionings and a capability set, where functionings are the various things that a person may value doing or being (for example, being adequately nourished, free from avoidable disease, and able to take part in the life of the community) and the capability set is the set of alternative functioning vectors available to her.

The proposals of Rawls and Sen differ, but formally they are closely related; social alternatives are characterized by a vector of valuable elements assigned to each individual. However, this raises the fundamental question of how to trade off gains and losses in the various dimensions for each individual. On possibility, as first suggested by Rawls (1971), is to establish an objective index as the basis for interpersonal comparisons in a theory of justice. The problem with this approach, as observed by Gibbard (1979), is that this in general will violate the Pareto principle. Some people will have preferences that are in disagreement with how the index implicitly makes the trade-off, and thus we face what is commonly named the indexing impasse (Sen 1996a; Plott 1978; Blair 1988; Arneson 1990). Sen suggests that the indexing impasse follows from not taking note of the citizens’ preferences when constructing the index, and he argues in favour of an intersection approach which articulates only those judgements that are shared implications of all the preferences present in society. However, as shown by Fleurbaey and Trannoy (2000), Brun and Tungodden (2004), and Pattanaik and Xu (2007), this approach does not solve the problem. In any society where people have heterogenous preferences, the intersection approach runs into a conflict with the Pareto principle.

A related argument has been put forward by Kaplow and Shavell (2001, 2002). They argue that any notion of fairness or justice that implies a violation of the Pareto indifference principle will also imply a violation of the standard Pareto principle if we accept a minimal continuity condition. They apply this insight to argue against any notion of fairness or justice that does not rely on individual utilities. However, there are alternatives to welfarism that are consistent with the Pareto principle (Fleurbaey et al. 2003). In particular, there is a literature on fair allocation which exploits the fact that with a richer description of the social alternatives we may apply considerations that rely on the shape of the indifference curves of individuals when establishing a justice ranking (Fleurbaey 2003; Fleurbaey et al. 2005; Fleurbaey and Maniquet 2006). This approach violates Arrow’s independence of irrelevant alternatives, and thus shows that this condition is far from innocent in an analysis of justice.

If we now turn to the question of how much weight to assign to the worse off, then the answer may depend on our assumptions about the informational framework (Bossert and Weymark 2002). If we assume that there is a one-dimensional measure of individual benefits (which may be utility) and no constraints on interpersonal comparability, then there is a vast number of theories of justice satisfying the Pareto principle. Hence, we need to impose other ethical conditions on the justice ranking in order to choose among the set of possible theories. One possibility is to appeal to conditions that only cover two-person situations, that is, situations where only the benefits of two persons differ in a comparison of two social alternatives, and it turns out that these conditions are extremely powerful in an analysis of this kind (d’Aspremont 1985). By way of illustration, the utilitarian and the leximin ranking follows almost directly from assuming two-person utilitarianism and two-person leximin within such a framework.

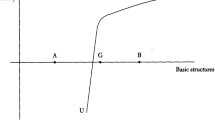

Within this informational framework, one may also show that any aggregative theory faces what we may name the tyranny of aggregation (Tungodden 2003), whereby the interests of the worse off may be outweighed by the interests of a sufficiently large number of better off, even though the gain of each of the better off is infinitesimal. Although the tyranny of aggregation is well-known in the context of utilitarianism, it is important to note that this applies to any aggregative approach to social choices, including any aggregative prioritarian rule. This raises the question of whether an aggregative approach can constitute the basis of a theory of justice.

Justice and Non-Aggregation

A core element in Rawls’s theory of justice is precisely that each person possesses an inviolability that makes aggregation impermissible. This is expressed both in the absolute priority assigned to the fulfilment of basic liberties and in the difference principle. Rawls aimed at justifying a non-aggregative approach by a constructive theory whereby people choose fairness principles behind a veil of ignorance. An extensive literature has questioned this conclusion, and following Harsanyi (1955) it is commonly argued that the veil of ignorance approach implies some version of utilitarianism (Weymark 1991; Broome 1991; Mongin 2001; Mongin and d’Aspremont 2002).

However, there are other ways of justifying a non-aggregative approach to distributive justice. One possibility is to combine a concern for equality promotion with a concern for Pareto efficiency (Barry 1989). Tungodden and Vallentyne (2005) have investigated this approach, where the basic idea is that distributive conflicts ought to be solved by choosing the more equal distribution. They show that any consistent theory of justice satisfying this approach has to assign strict priority to the worst off in society. This result is closely related to the formal results developed by Hammond (1975) on extreme inequality aversion, and questions the claim of some philosophers that the leximin principle is not consistent with a concern for equality (McKerlie 1994).

Another interesting non-aggregative approach has been suggested by Nagel (1979) and Scanlon (1982, 1998). They both argue that justice requires pairwise comparisons of individual claims, where the just solution is to satisfy the individual with the most urgent claim. In other words, they reject the argument that the number of persons with a particular claim should count (Taurek 1977). They do, however, defend the view that, in order to measure the urgency of a claim, one should take into account both gains and losses and the absolute circumstances of an individual. Hence, the aim is to outline a theory of justice that lies in the middle ground between leximin and the standard aggregative perspective. It turns out, however, that it is impossible to establish such a middle ground within a framework satisfying some basic consistency conditions (Tungodden 2003).

Frankfurt (1987) proposes the doctrine of sufficiency, which says that justice plays no role if everyone has enough. This may be interpreted as a non-aggregative approach, whereby absolute priority is assigned to those below the sufficiency threshold. There are two fundamental and interlinked issues within this framework. First, one needs to define what it means to have enough. Second, one needs to justify why justice is not an issue among those who have enough. Anderson (1999), who appeals to the notion of democratic equality, may be seen as one way of developing Frankfurt’s proposal, where people have enough if they have what is sufficient to stand as an equal in society. Crisp (2003), on the other hand, relates the idea of sufficiency to the notion of compassion, where priority should be given to the worse off only when their circumstances warrant the compassion of an impartial spectator. Underlying both these proposals is the perspective that the role of justice is limited, which of course does not exclude the possibility that there are other reasons for caring about the circumstances of people above the sufficiency threshold.

The standard view within economics is to think of justice as unlimited, that is, as relevant independent of people’s circumstances. However, it is commonly recognized that by far the most pressing problem of justice in the modern world is the presence of poverty, and this has caused a substantial literature on the definition and measurement of this concept (Sen and Foster 1997). Given any definition of poverty, absolute or relative, there is then the further question of how to fit this into a more general theory of justice. One possibility is a non-aggregative approach, where strict priority is given to the alleviation of poverty but where this is combined with a concern for distributive justice among those who do not live in poverty. Interestingly, this scheme is formally closely related to the structure of the difference principle as suggested by Rawls (1971). Rawls proposed that a relative threshold should define the worst-off group, and that we should assign strict priority to the expectations of this group (and not only the worst-off individual). However, it turns out that a relative definition of the worst-off group does not make room for an interpretation of the difference principle that differs from the standard leximin interpretation (Tungodden 1999). Hence, an absolute threshold is needed to build an alternative non-aggregative theory of justice to leximin.

Any non-aggregative theory of justices faces what we may call the tyranny of non-aggregation, that is, it sometimes justifies that minor improvements in the lives of some people should outweigh great losses for any number of better-off people. This may seem as a knock-down argument against a non-aggregative approach. However, it is important to have in mind that by rejecting a non-aggregative approach one accepts the tyranny of aggregation, since there does not exist any reasonable theory of justice that avoids both the tyranny of aggregation and the tyranny of non-aggregation.

Libertarianism, Rights, and Consequentialism

We have argued that a non-aggregative theory of justice has to assign absolute priority to the worse off, and thus such a theory provides a strong protection of the rights and liberties of this group. However, this may imply the violation of the rights of others. Libertarianism, on the other hand, holds that all agents are, initially at least (for example, prior to engaging in any commitments or unjust actions), full self-owners, and that any violation of full self-ownership is unjust. The core idea of full self-ownership is that agents own themselves in just the same way that they can fully own inanimate objects.

The modern interest in libertarianism was initiated by the work of Nozick (1974), who not only defended full self-ownership but also the view that people should be free to appropriate parts of the external world as long as no one be left worse off with the appropriation than she would be if the thing were in common use. This view of just appropriation of the external world has recently been challenged by left-libertarians, who argue that people have joint ownership of natural resources (Moulin and Roemer 1989; Steiner 1994; Vallentyne and Steiner 2000; Otsuka 2003). If we accept the premise of joint ownership, then it follows that natural resources may be justly appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the other members of society.

The work of Nozick (1974) was partly motivated by Sen’s liberal paradox (Sen 1970b; Gibbard 1974), where Sen shows that there is a conflict between respecting the Pareto principle and protecting a private sphere to each individual in society. This work has initiated a large literature, which has studied alternative formulations of individual rights. In particular, it has been argued that rights should be formulated as the admissibility of actions or strategies of individuals and not as the right to impose one’s preferences on the ranking of a particular set of social alternatives (Gaertner et al. 1992). However, as pointed out by Sen (1992b, 1996a), even though this provides an interesting alternative formulation of rights, it does not in itself eliminate the tension between the Pareto principle and individual rights.

Libertarianism in its various forms provides one way of justifying individual rights, but the right-based perspective is certainly not exclusive to libertarianism (see, for example, Rawls 1971, 1993; Kolm 1996; van Hees and Dowding 2003). Moreover, a rights-based perspective does not necessarily have to be non-consequentialistic in the sense that it imposes side constraints that cannot be overridden by other considerations of justice. It is possible to defend a consequentialistic rights-based approach, where the best overall outcome, as judged from an impersonal standpoint which gives equal weight to the interest of everyone, is to minimize the violations of some basic rights or liberties (Scheffler 1988). In fact, it has also been argued that side constraints and agent relativity can be accommodated by consequential reasoning if we adopt a positional view of consequences (Sen 1982, 1993). Finally, we should note that rights and liberties also may be justified on instrumental grounds, as a way of generating good consequences.

Intergenerational Justice and International Justice

The intergenerational perspective introduces several interesting challenges to a theory of justice (Parfit 1984). First, we have to consider how to deal with the non-identity problem of future people, which questions whether people that are born as a result of a particular set of policies can be harmed by these policies, given that they would not have been born at all otherwise. Second, we have to consider how to avoid the repugnant conclusion, namely, that for any given affluent population there is a better world with more people, but where everyone has an arbitrarily low level of utility or well-being. This conclusion follows from two intuitively plausible conditions, namely, that we make the world better by bringing in people who have a life worth living and that we do not make the world worse by making it more equal (at least as long as this does not reduce the total amount of utility in society). Blackorby et al. (1997, 2005) propose critical-level utilitarianism as the best possible solution to these problems, where critical-level utilitarianism disvalues only individuals whose utility level is below some fixed, low but positive threshold.

The literature on intergenerational justice has considered how to formulate a criterion of justice when there is an infinite number of generations. The basic problem was raised by Diamond (1965), who proved that within this framework it is impossible to construct a social welfare function that satisfies the Pareto principle, a principle of intergenerational equity and continuity. Basu and Mitra (2003) strengthen this result by proving that the continuity condition is superfluous. In other words, the fundamental conflict is between the Pareto principle an intergenerational equity. However, the literature also contains positive results, which show that a criterion for intergenerational justice can be formulated with an infinite horizon if one moves away from the framework of a social welfare function (Asheim et al. 2001; Asheim and Tungodden 2004; Basu and Mitra 2003, 2007; Bossert et al. 2007; Fleurbaey and Michel 2003).

Rawls (1971) limited his theory of justice to the circumstances of a nation, and recently this has been questioned by a number of philosophers (Pogge 1989, 1992, 1994, 2001). They find any distinction between people based on territory arbitrary, and thus argue in favour of applying Rawls’s principles of justice on the global scale. Consequently, they claim that the situation of the worst-off members of the global, rather than the domestic, society ought to be the starting point for considerations of justice. This view has been rejected by Rawls (1999), who argues that there is no basic structure in the international arena that can be the primary subject of social justice, and the difference principle cannot be a demand of justice in the international realm because, among other things, the justification of the difference principle has merit only between persons who cooperate in the way that this is done within the nation state.

Concluding Remarks

The normative literature on justice has expanded enormously in recent years, with an extremely fruitful exchange of ideas between the disciplines of economics and philosophy. As a result, we now have a much richer understanding of how to think about the various possible conceptions of a just society. Still, there are many unresolved questions in the literature. Let me briefly mention three of them. First, there is a need further study of how to combine egalitarian ideas of responsibility with a concern for efficiency. Basic economic theory tells us that the efficient solution is to let individuals face the actual consequences of their choices, but this is clearly to hold individuals responsible for too much in many situations. How should we deal with this tension in a just society? Second, there is a need for further study of the metric of individual advantage. There are a number of suggestions present in the literature, including primary goods, basic needs, functionings and capabilities, but still need for more research on how to combine these approaches with a respect for individual preferences and choices. Finally, there is a need for further analysis of the prioritarian proposal. The core question within prioritarianism is how much more weight to attach to the worse off, and presently we lack a clear understanding of how to move forward on this issue.

Bibliography

Anderson, E. 1999. What is the point of equality? Ethics 109: 287–337.

Arneson, R. 1989. Equality and equal opportunity for welfare. Philosophical Studies 56: 159–194.

Arneson, R. 1990. Primary goods reconsidered. Noûs 24: 429–454.

Arrow, K.J. 1951. Social choice and individual values, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley. 1963.

Asheim, G.B., and B. Tungodden. 2004. Resolving distributional conflicts between generations. Economic Theory 24: 221–230.

Asheim, G.B., W. Bucholz, and B. Tungodden. 2001. Justifying sustainability. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 2: 252–268.

Barry, B. 1989. Theories of justice. Berkley: University of California Press.

Basu, K., and T. Mitra. 2003. Aggregating infinite utility streams with intergenerational equity: The impossibility of being Paretian. Econometrica 32: 1557–1563.

Basu, K., and T. Mitra. 2007. Utilitarianism for infinite utility streams: A new welfare criterion and its axiomatic characterization. Journal of Economic Theory 133: 350–373.

Binmore, K. 2005. Natural justice. New York: Oxford University Press.

Blackorby, C., W. Bossert, and D. Donaldson. 1997. Critical-level utilitarianism and the population–ethics dilemma. Economics and Philosophy 13: 197–230.

Blackorby, C., W. Bossert, and D. Donaldson. 2005. Population issues in social choice theory, welfare economics and ethics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Blair, D.H. 1988. The primary-goods indexation problem in Rawls’s theory of justice. Theory and Decision 24: 239–252.

Bossert, W. 1995. Redistribution mechanisms based on individual characteristics. Mathematical Social Sciences 29: 1–17.

Bossert, W., and M. Fleurbaey. 1996. Redistribution and compensation. Social Choice and Welfare 13: 343–355.

Bossert, W., and J.A. Weymark. 2002. Utility in social choice. In Handbook of utility theory, ed. S. Barbera, P. Hammond, and C. Seidl. London: Kluwer.

Bossert, W., Y. Sprumont, and K. Suzumura. 2007. Ordering infinite utility streams. Journal of Economic Theory 135: 579–589.

Broome, J. 1991. Weighing goods. Equality, uncertainty, and time. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Broome, J. 2007. Equality versus priority: A useful distinction. In Fairness and goodness in health, ed. C. Murray and D. Wikler. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Brun, B.C., and B. Tungodden. 2004. Non-welfarist theories of justice: Is ‘the intersection approach’ a solution to the indexing impasse? Social Choice and Welfare 22: 1–12.

Camerer, C.F. 2003. Behavioral game theory: Experiments in strategic interaction. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cappelen, A., and B. Tungodden. 2006. Relocating the responsibility cut: Should more responsibility imply less redistribution. Politics, Philosophy and Economics 5: 353–362.

Cohen, G.A. 1989. On the currency of egalitarian justice. Ethics 99: 906–944.

Crisp, R. 2003. Equality, priority, and compassion. Ethics 113: 745–763.

d’Aspremont, C. 1985. Axioms for social welfare orderings. In Social goals and social organization: Essays in memory of Elisha Pazner, ed. L. Hurwicz, D. Schmeidler, and H. Sonnenschein. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

d’Aspremont, C., and L. Gevers. 1977. Equity and the informational basis of collective choice. Review of Economic Studies 44: 199–210.

Dennet, D. 2003. Freedom evolves. London: Penguin Books.

Diamond, P. 1965. The evaluation of infinite utility streams. Econometrica 33: 170–177.

Dworkin, R. 1981. What is equality? Parts. I and II. Philosophy and Public Affairs 10: 283–345.

Dworkin, R. 2002. Sovereign virtue revisited. Ethics 113: 106–143.

Fleurbaey, M. 1995a. Equal opportunity or equal social outcome. Economics and Philosophy 11: 25–55.

Fleurbaey, M. 1995b. The requisites of equal opportunity. In Social choice welfare, and ethics, ed. W.A. Barnett et al. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fleurbaey, M. 1995c. Three solutions for the compensation problem. Journal of Economic Theory 65: 505–521.

Fleurbaey, M. 2002. Equality of resources revisited. Ethics 113: 82–105.

Fleurbaey, M. 2003. On the informational basis of social choice. Social Choice and Welfare 21: 347–384.

Fleurbaey, M. 2007. Equality versus priority: How relevant is the distinction? In Fairness and goodness in health, ed. C. Murray and D. Wikler. Geneva: World Health Organization (forthcoming).

Fleurbaey, M., and F. Maniquet. 1996. Fair allocation avec unequal production skills: The no-envy approach to compensation. Mathematical Social Sciences 32: 71–93.

Fleurbaey, M., and F. Maniquet. 1999. Fair allocation with unequal production skills: The solidarity approach to compensation. Social Choice and Welfare 16: 569–583.

Fleurbaey, M., and F. Maniquet. 2006. Fair income tax. Review of Economic Studies 73: 55–83.

Fleurbaey, M., and F. Maniquet. 2008. Compensation and responsibility. In Handbook of social choice and welfare, ed. K.J. Arrow, A.K. Sen, and K. Suzumura, vol. 2. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Fleurbaey, M., and P. Michel. 2003. Intertemporal equity and the extension of the Ramsey criterion. Journal of Mathematical Economics 39: 777–802.

Fleurbaey, M., and A. Trannoy. 2000. The impossibility of a Paretian egalitarian. Social Choice and Welfare 21: 243–263.

Fleurbaey, M., K. Suzumura, and K. Tadenuma. 2005. Arrovian aggregation in economic environments: How much should we know about indifference surfaces? Journal of Economic Theory 124: 22–44.

Fleurbaey, M., B. Tungodden, and H.F. Chang. 2003. Any non-welfarist method of policy assessment violates the Pareto principle: A comment. Journal of Political Economy 111: 1382–1385.

Frankfurt, H. 1987. Equality as a moral ideal. Ethics 98: 21–43.

Gaertner, W., P.K. Pattanaik, and K. Suzumura. 1992. Individual rights revisited. Economica 59: 161–177.

Gibbard, A. 1974. A Pareto-consistent libertarian claim. Journal of Economic Theory 7: 388–410.

Gibbard, A. 1979. Disparate goods and Rawls’ difference principle: A social choice theoretic treatment. Theory and Decision 11: 267–288.

Hammond, P. 1975. A note on extreme inequality aversion. Journal of Economic Theory 11: 119–132.

Harsanyi, J.C. 1955. Cardinal welfare, individualistic ethics, and interpersonal comparisons of utility. Journal of Political Economy 63: 309–321.

Kaplow, L., and S. Shavell. 2001. Any non-welfarist method of policy assessment violates the Pareto principle. Journal of Political Economy 109: 281–286.

Kaplow, L., and S. Shavell. 2002. Fairness versus welfare. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kolm, S.-C. 1996. Modern theories of justice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Konow, J. 2003. Which is the fairest one of all? A positive analysis of justice theories. Journal of Economic Literature 41: 1188–1239.

McKerlie, D. 1994. Equality and priority. Utilitas 6: 25–42.

Mongin, P. 2001. The impartial observer theorem of social ethics. Economics and Philosophy 17: 147–180.

Mongin, P., and C. d’Aspremont. 2002. Utility theory and ethics. In Handbook of utility theory, ed. S. Barberà, P. Hammond, and C. Seidl, vol. 1. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Moulin, H., and J. Roemer. 1989. Public ownership of the external world and private ownership of self. Journal of Political Economy 97: 347–367.

Nagel, T. 1979. Mortal questions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nagel, T. 2002. Concealment and exposure & other essays. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nozick, R. 1974. Anarchy, state and utopia. New York: Basic Books.

Ooghe, E., Schokkaert, E. and Van de gaer, D. 2006. Equality of opportunity versus equality of opportunity sets. Social Choice and Welfare.

Otsuka, M. 2003. Libertarianism without inquality. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Parfit, D. 1984. Reasons and persons. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Parfit, D. 1995. Equality or priority. Lindley lecture, University of Kansas. Reprinted in The ideal of equality, ed. M. Clayton and A. Williams. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000.

Pattanaik, P.K., and Y. Xu. 2007. Minimal relativism, dominance, and standard of living comparisons based on functionings. Oxford Economic Papers 59: 354–374.

Plott, C.R. 1978. Rawls’s theory of justice: an impossibility result. In Decision theory and social ethics: Issues in social choice, ed. H. Gottinger and W. Leinfellner. Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

Pogge, T. 1989. Realizing rawls. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Pogge, T. 1992. Cosmopolianism and sovereignty. Ethics 103: 48–75.

Pogge, T. 1994. An egalitarian law of peoples. Philosophy and Public Affairs 23: 195–224.

Pogge, T., eds. 2001. Global justice. Oxford: Blackwell.

Rawls, J. 1971. A theory of justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rawls, J. 1993. Political liberalism. New York: Columbia University Press.

Rawls, J. 1999. The law of peoples. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Roemer, J. 1985. Equality of talent. Economics and Philosophy 1: 151–187.

Roemer, J. 1993. A pragmatic theory of responsibility for the egalitarian planner. Philosophy and Public Affairs 22: 146–166.

Roemer, J. 1996. Theories of distributive justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Roemer, J. 1998. Equality of opportunity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Roemer, J. 2002a. Egalitarianism against the veil of ignorance. Journal of Philosophy 99: 167–184.

Roemer, J. 2002b. Equality of opportunity: A progress report. Social Choice and Welfare 19: 455–471.

Scanlon, T. 1982. Contractualism and utilitarianism. In Utilitarianism and beyond, ed. A. Sen and B. Williams. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Scanlon, T. 1998. What we owe each other. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Scanlon, T. 2000. The diversity of objections to inequality. In The ideal of equality, ed. M. Clayton and A. Williams. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Scheffler, S. 1988. Consequentialism and its critics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sen, A. 1970a. Collective choice and social welfare. San Francisco: Holden Day.

Sen, A. 1970b. The impossibility of a Paretian liberal. Journal of Political Economy 78: 152–157.

Sen, A. 1979. Utilitarianism and welfarism. Journal of Philosophy 9: 463–489.

Sen, A. 1982. Rights and agency. Philosophy and Public Affairs 11: 3–39.

Sen, A. 1985. Commodities and capabilities. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Sen, A. 1992a. Inequality reexamined. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sen, A. 1992b. Minimal liberty. Economica 59: 139–159.

Sen, A. 1993. Positional objectivity. Philosophy and Public Affairs 22: 126–145.

Sen, A. 1996a. Rights: Formulations and consequences. Analyse & Kritik 18: 153–170.

Sen, A. 1996b. Individual preferences as the basis of social choice. In Social choice re-examined, ed. K. Arrow, A. Sen, and K. Suzamura. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Sen, A., and J. Foster. 1997. On economic inequality. Expanded ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Skyrms, B. 1996. Evolution of the social contract. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Skyrms, B. 2003. The stage hunt and the evolution of social structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Steiner, H. 1994. An essay on rights. Oxford: Blackwell.

Taurek, J. 1977. Should the numbers count? Philosophy and Public Affairs 6: 293–316.

Temkin, L. 1993. Inequality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Temkin, L. 2000. Equality, priority, and the levelling down objection. In The ideal of equality, ed. M. Clayton and A. Williams. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tungodden, B. 1999. The distribution problem and Rawlsian reasoning. Social Choice and Welfare 16: 599–614.

Tungodden. 2003. The value of equality. Economics and Philosophy 19: 1–44.

Tungodden, B. 2005. Responsibility and redistribution: The case of first best. Social Choice and Welfare 24: 33–44.

Tungodden, B., and P. Vallentyne. 2005. On the possibility of Paretian egalitarianism. Journal of Philosophy 102: 126–154.

Vallentyne, P., and H. Steiner, eds. 2000. Left Libertarianism and its critics: The contemporary debate. New York: Palgrave Publishers.

Van de gaer, D. 1993. Equality of opportunity and investment in human capital. Ph.D thesis, K.U. Leuven.

Van Hees, M., and K. Dowding. 2003. The construction of rights. American Political Science Review 97: 281–293.

Van Parijs, P. 1995. Real freedom for all. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Weymark, J.A. 1991. A reconsideration of the Harsanyi–Sen debate on utilitarianism. In Interpersonal comparisons of well-being, ed. J. Elster and J.E. Roemer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Copyright information

© 2018 Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry

Tungodden, B. (2018). Justice (New Perspectives). In: The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_2301

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_2301

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-349-95188-8

Online ISBN: 978-1-349-95189-5

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceReference Module Humanities and Social SciencesReference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences