Abstract

Chronic constipation is a common and disabling problem in many patients all over the world, in particular in elderly. There are two main pathophysiologies, but with possible overlapping situations: disorders of transit and evacuation disorders.

Functional constipation has many causes, including the kind of diet and lifestyle, and it can also be secondary to medications, other many medical conditions, and/or disease. Alarm symptoms sometimes coexist, and it is mandatory to underline these conditions in order to manage the therapeutical approach properly.

Treatment options for chronic constipation include changes in lifestyle, drugs, and rehabilitation of the perineum as well as biofeedback therapies; commonly first-level therapeutical approach is undertaken before the diagnosis of chronic constipation will be cleared, but understanding its etiology is necessary to determine the most appropriate and tailored therapeutic option; history and physical examination of the patients can orientate in an intricate instrumental diagnostic approach which consists of imaging and functional tests.

Our aim is try to clarify on these complicated diagnostic choices in order to optimize therapeutical interventions.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Pelvic Organ Prolapse

- Pelvic Floor Muscle

- Chronic Constipation

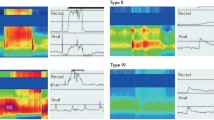

- Anorectal Manometry

- Functional Constipation

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Chronic Constipation and Obstructed Defecation: Definition, Diagnosis and Clinical Approach

Chronic constipation is a worldwide problem increasing with age. It can be either primary or secondary. It is often, erroneously, considered as a single disease but it is a complex and multifaceted syndrome. There are many different causes able to induce secondary constipation (Tables 24.1 and 24.2).

The term “primary constipation” itself hides different conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C), functional constipation, functional defecation disorders, and rectal hyposensitivity (Bellini et al. 2015; Bharucha et al. 2006; Longstreth et al. 2006) (Tables 24.3 and 24.4).

Particularly IBS-C is characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort improved by defecation, whereas functional constipation is a functional bowel disorder that presents as persistently difficult, infrequent, or incomplete defecation. Functional defecation disorders are characterized by paradoxical contraction or inadequate relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles during attempted defecation (dyssynergic defecation ) or inadequate propulsive forces during attempted defecation (inadequate defecatory propulsion) (Bharucha et al. 2006).

Rectal hyposensitivity is a relatively new disorder defined by Gladman (Gladman et al. 2003) as an elevation beyond the normal range in the perception of at least one of the sensory threshold volumes during anorectal manometry. There are as yet no specific criteria that can differentiate the subtypes of chronic constipation based on history (Bharucha et al. 2006). Also performing a full assessment of defecation using specific tests (e.g., anorectal manometry, colonic transit time, and defecography) may not distinguish these different conditions (Wong et al. 2010; Rey et al. 2014; Jones et al. 2007; Gambaccini et al. 2013). However, a careful attempt to understand the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the constipation of each patient is mandatory in order to suggest an effective therapy. This should be strictly tailored to each individual patient and therefore different from one patient to another (Bellini et al. 2015).

Even if there are no specific criteria that can definitely distinguish among the different subtypes of chronic constipation, a careful medical history should always be collected. It is the first approach to the patient and is aimed to detect symptoms and events possibly linked to the onset of symptoms themselves (Bove et al. 2012).

History can also identify alarm symptoms (Table 24.5), such as weight loss, bloody stools, anemia, or a family history of colon cancer and conditions and/or diseases potentially associated with constipation, such as dietary mistakes (Altringer et al. 1995); low physical activity (Diamant et al. 1999); the use of constipating drugs; metabolic, psychiatric, or neurological diseases; and previous perineal-pelvic-abdominal or obstetric-gynecological surgery (Tables 24.1 and 24.2). In case of alarm symptoms/signs, colonoscopy is recommended (Table 24.10).

Also assessing the stool form using the Bristol stool form score (Lewis and Heaton 1997) is of paramount importance to obtain an objective evaluation; moreover stool consistency is considered an indicator of colonic transit ; hence, it can address the diagnosis.

A physical examination is essential in the initial workup of a patient with chronic constipation (Lindberg et al. 2011). The examination can detect a possible gastrointestinal mass and should include inspection of the anorectal region and exploration of the rectum. This process can provide evidence of external signs of anal disease, pelvic organ prolapse, or descending perineum syndrome. A digital rectal examination should detect any signs of organic disease or obstructed defecation (rectal masses, fecal impaction, stricture, rectal intussusception, or rectocele). The examination is particularly important if functional alterations in defecation are suspected in order to evaluate puborectal and anal sphincter activity.

Blood tests do not provide useful input in functional constipation but can be performed to exclude conditions of secondary chronic constipation (Bove et al. 2012) (Table 24.2). They also can be mandatory when alarm symptoms are present.

Once excluded on a clinical basis organic lesions and secondary constipation, many patients will benefit from abolishing or reducing medications that cause constipation and recommending changes in lifestyle and diet with correct fluid (at least 1.5 l/day) and fiber (25 mg/day) intake (Table 24.6).

If this management is not sufficient, it is mandatory to move to a second step encompassing the use of fiber supplementations and osmotic laxatives .

If also these therapies are ineffective, it is possible to use old (stimulant, softening, or saline) laxatives or new prokinetics or prosecretory agents even if in this subset of patients, further tests such as anorectal manometry and/or entero-defecography and/or colonic transit time are advisable, in order to better characterize the type of constipation (Tables 24.7, 24.8, and 24.9) and to evaluate other therapeutic options (e.g., pelvic floor rehabilitation , sacral nerve stimulation, anorectal surgery) (Ratto et al. 2015); colpo-cysto-entero-defecography (Altringer et al. 1995; Maglinte et al. 1997), magnetic resonance (MR) defecography (Lienemann et al. 1997), and dynamic transperineal ultrasonography (DTP-US) (Beer-Gabel et al. 2002, 2004; Dietz and Steensma 2005; Brusciano et al. 2007) are also available and increasingly utilized. Colonic and/or gastrojejunal manometry should be performed in patients with serious slow-transit constipation because they can be helpful in the diagnosis and in decisions regarding therapy (whether conservative or surgical) (Bove et al. 2012).

The global approach to chronic constipation integrating available tests and treatments is summarized in Table 24.10.

References

Altringer WE, Saclarides TJ, Dominguez JM, Brubaker LT, Smith CS (1995) Four-contrast defecography: pelvic “floor-oscopy”. Dis Colon Rectum 38:695–699

Beer-Gabel M, Teshler M, Barzilai N, Lurie Y, Malnick S, Bass D, Zbar A (2002) Dynamic transperineal ultrasound in the diagnosis of pelvic floor disorders: pilot study. Dis Colon Rectum 45:239–245

Beer-Gabel M, Teshler M, Schechtman E, Zbar AP (2004) Dynamic transperineal ultrasound vs. defecography in patients with evacuatory difficulty: a pilot study. Int J Colorectal Dis 19:60–67

Bellini M, Gambaccini D, Usai-Satta P, De Bortoli N, Bertani L, Marchi S (2015) Stasi C; Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic constipation: fact and fiction. World J Gastroenterol 21(40):11362–11370

Bharucha AE, Wald A, Enck P, Rao S (2006) Functional anorectal disorders. Gastroenterology 130:1510–1518

Bove A, Pucciani F, Bellini M, Battaglia E, Bocchini R, Altomare DF, Dodi G, Sciaudone G, Falletto E, Piloni V, Gambaccini D, Bove V (2012) Consensus statement AIGO/SICCR: diagnosis and treatment of chronic constipation and obstructed defecation (part I: diagnosis). World J Gastroenterol 18:1555–1564

Brusciano L, Limongelli P, Pescatori M, Napolitano V, Gagliardi G, Maffettone V, Rossetti G, Del Genio G, Russo G, Pizza F (2007) Ultrasonographic patterns in patients with obstructed defaecation. Int J Colorectal Dis 22:969–977

Diamant NE, Kamm MA, Wald A et al (1999) AGA technical review on anorectal testing techniques. Gastroenterology 116:735–760

Dietz HP, Steensma AB (2005) Posterior compartment prolapse on two-dimensional and three-dimensional pelvic floor ultrasound: the distinction between true rectocele, perineal hypermobility and enterocele. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 26:73–77

Gambaccini D, Racale C, Salvadori S, Alduini P, Bassotti G, Battaglia E, Bocchini R, Bove A, Pucciani F, Bellini M; the Italian Constipation Study Group (2013) Chronic constipation: Rome III criteria and what patients think. Are we talking the same language? United European. Gastroenterol J 1 (Supplement 1): 20–21

Gladman MA, Scott SM, Chan CL, Williams NS, Lunniss PJ (2003) Rectal hyposensitivity: prevalence and clinical impact in patients with intractable constipation and fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 46:238–246

Jones MP, Post J, Crowell MD (2007) High-resolution manometry in the evaluation of anorectal disorders: a simultaneous comparison with water-perfused manometry. Am J Gastroenterol 102:850–855

Lewis SJ, Heaton KW (1997) Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol 2:920–924

Lienemann A, Anthuber C, Baron A, Kohz P, Reiser M (1997) Dynamic MR colpocystorectography assessing pelvic-floor descent. Eur Radiol 7:1309–1317

Lindberg G, Hamid SS, Malfertheiner P, Thomsen OO, Fernandez LB, Garisch J, Thomson A, Goh KL, Tandon R, Fedail S, Wong BC, Khan AG, Krabshuis JH, LeMair A (2011) World Gastroenterology Organisation global guideline: constipation – a global perspective. J Clin Gastroenterol 45:483–487

Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC (2006) Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 130:1480–1491

Maglinte DD, Kelvin FM, Hale DS, Benson JT (1997) Dynamic cystoproctography: a unifying diagnostic approach to pelvic floor and anorectal dysfunction. AJR Am J Roentgenol 169:759–767

Pehl C, Schmidt T, Schepp W (2002) Slow transit constipation: more than one disease? Gut 51:610

Ratto C, Ganio E, Naldini G, GINS (2015) Long-term results following sacral nerve stimulation for chronic constipation. Colorectal Dis 17:320–328

Rey E, Balboa A, Mearin F (2014) Chronic constipation, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and constipation with pain/discomfort: similarities and differences. Am J Gastroenterol 109:876–884

Wong BS, Manabe N, Camilleri M (2010) Role of prucalopride, a serotonin (5-HT(4)) receptor agonist, for the treatment of chronic constipation. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 3:49–56

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this entry

Cite this entry

Manfredi, G., Londoni, C., Bellini, M., Buscarini, E. (2017). Diagnostic Algorithm for Constipation and Obstructed Defecation. In: Ratto, C., Parello, A., Donisi, L., Litta, F. (eds) Colon, Rectum and Anus: Anatomic, Physiologic and Diagnostic Bases for Disease Management. Coloproctology, vol 1. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-09807-4_29

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-09807-4_29

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-09806-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-09807-4

eBook Packages: MedicineReference Module Medicine