Abstract

Background

Male breast cancer is a rare event, accounting for approximately 1% of all breast carcinomas. Although men with breast cancer had poorer survival when compared with women, data on prognosis principally derive from retrospective studies and from extrapolation of female breast cancer series. We reported the case of a very long survival patient.

Case presentation

A caucasian 42-year-old man underwent radical mastectomy with axillary dissection for breast cancer in 1993. Pathologic stage was pT4pN0M0 infiltrating ductal carcinoma of right breast without lymph nodes metastases. Biological characterization was not available. He received adjuvant treatment with chemotherapy, six cycles of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil, then endocrine therapy with tamoxifen for 5 years and complementary radiotherapy. Then he began clinical-instrumental follow up. In May 1996, a computed tomography scan showed multiple lung metastases. Hereafter he received several oncologic treatment including seven chemotherapy and five endocrine therapy lines with two re-challenge of endocrine therapy. In October 2007 further lung progression was showed and a biopsy was performed to characterize the disease. Histological examination confirmed breast cancer metastases, immunohistochemistry showed positive staining for estrogen receptor, negative for progesterone receptor and human epithelial growth factor receptor 2, proliferative index was 21%. In April 2013, bone disease progression was evident and he received radiant treatment to sacral spine. In May 2014 an off-label treatment with exemestane and everolimus combination was approved by Ethics Committee of the Marche Region. The patient received treatment for 3 months with evident clinical benefit to subcutaneous lesions of the chest wall that were not visible nor palpable on physical examination after 1 month of treatment.

Conclusion

That is the case of long survival male breast cancer patient with luminal B subtype and no BRCA mutations. He achieved higher progression free survival with endocrine therapy creating the rationale for last line treatment with everolimus and exemestane combination. Attending conclusive results from ongoing studies, everolimus and exemestane should not be used routinely in male metastatic breast cancer patients, but taking into account for selected cases. At the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of male beast cancer treated with exemestane and everolimus combination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Male breast cancer (MBC) is a rare event, accounting for approximately 1% of all breast carcinomas and less than 1% of all male cancers [1–3]. Recent data by The International Agency for Research on Cancer, a division of the World Health Organization, demonstrated the global incidence of MBC stands at nearly 8000 cases. For Europe, this equates to 3750 cases of MBC [4]. In 2014 in the United States, 2360 cases were estimated, while the lifetime risk of men getting breast cancer is 1 in 1000 [1]. These figures are significantly lower (<1%) than the incidence of breast cancer (BC) in women, which represents 11.6% of the global cancer incidence in 2014 [5].

Men tend to present 5 years later than women do, commonly in the seventh decade [6, 7]. MBC incidence seems increasing and in the absence of formal epidemiological studies, reasons for the apparent rise could only be speculated [8]. A large population-based study of 2537 men with breast cancer, analyzed from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database, reported that over a 25 year period (1973–1998) the incidence of MBC increased significantly from 0.86 to 1.08 per 100,000 population in the United States [9].

MBC prognosis is reported to be poorer than female BC one, even if data mainly derived from retrospective studies and from extrapolation of female BC series. Endocrine therapy seems to be effective and many studies report that aromatase inhibitors (AIs) may be an effective and safe treatment option for hormonal receptor (HR) positive, metastatic male breast cancers progressing on tamoxifen [10–14].

Unfortunately, not all patients respond to first-line endocrine therapy (primary or de novo resistance), and even patients who have a response will eventually relapse (acquired resistance).

Everolimus, an mTOR inhibitor, in combination with exemestane demonstrated a 6-month improvement in women with resistance to non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors [15].

In clinical practice, this could be good rationale for the everolimus combination use to overcome the resistance, also in MBC, unfortunately until now there are no data in this setting of patients.

We report the case of a very long survival male breast cancer patient who was affected by hormone-sensitive disease and received an off label combination treatment with everolimus plus exemestane, as a 13th line of treatment, approved by Ethics Committee of the Marche Region (CERM).

According to our country’s legislation, since it was a retrospective study, with no direct patient involvement, the ethical approval and patients consent for the study were not required (Official Gazette No. 72 of March 26, 2012). The medical record was reviewed to find data on patient’s medical history and a written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s next of kin for publication of this Case Report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by Editor in Chief of this journal.

Case presentation

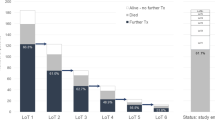

We describe the case of a 42-year-old Caucasian man who was diagnosed with BC in 1993. The patient reported a case of BC in his family, anyway without a medical history of risk factors for BC. In June 1993, he underwent to a radical mastectomy with axillary lymphadenectomy; histopathological examination confirmed infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the right breast with poor cellular differentiation, G3, large areas of necrosis, infiltration of subcutaneous tissue and muscular involvement. Biological characterization was not available. The final pathologic stage was pT4pN0(0/12)M0. He was given adjuvant treatment with six cycles of CMF (cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2, methotrexate 40 mg/m2, fluorouracil 600 mg/m2) administered day 1–8, every 4 weeks, endocrine therapy with tamoxifen 20 mg daily for 5 years and complementary radiotherapy on the chest wall. In May 1996, during follow-up, a computed tomography (CT) scan revealed multiple lung metastases. Hereafter the patient started a first-line weekly paclitaxel chemotherapy, obtaining a partial response. In March 1997, paclitaxel was stopped because of lung metastases progression and an endocrine therapy with megestrol was administered until January 2000 when it was discontinued for a vein thrombosis and switch to exemestane. In January 2001, a new CT showed a further progression of disease (PD). Epirubicin and docetaxel were administered until June 2001 when a further lung progression was revealed. Thus, patient was given letrozole, 2.5 mg daily, until January 2002 when his lung disease progressed. A course of vinorelbine was started but in December 2002 chemotherapy was interrupted for PD and a re-challenge with megestrol produced a partial response until October 2007 when disease progressed again. We performed a lung biopsy to confirm etiology and histological examination was positive for BC metastases, immunohistochemistry showed positive staining for the estrogen receptor (ER) 99%, negative for progesterone receptor (PR) 0, 1% and for herceptest (1+). Ki67 was 21%. In October 2007, a re-challenge was done with tamoxifen, previously used in the adjuvant setting, and in May 2008, with a stable disease and a poor compliance, it was suspended. In January 2009, lung metastases progressed and capecitabine was prescribed observing stable disease for 2 years.

From February 2011 until March 2013, a metronomic combination of cyclophosphamide and methotrexate was administered. In April 2013, bone and nodes metastases were diagnosed, then he received bone palliative radiotherapy.

In May 2013 carboplatin and zoledronic acid were given, but a progressive disease was observed in October 2013 (lung, subcutaneous metastases). A biopsy of skin lesions confirmed breast cancer metastases. We commenced eribuline for a total of six cycles with no clinical benefit. Consequently, we interrupted therapy for PD with pulmonary lymphangitis, pulmonary thromboembolism and significant deterioration of the patient’s clinical condition (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status, ECOG PS 2).

In May 2014 an off-label treatment with everolimus (EVE) and exemestane (EXE) was requested and approved by Ethics Committee of the Marche Region (CERM). After one month of treatment with everolimus, it was possible to highlight the complete response of the skin lesions had almost completely disappeared and were no longer palpable on physical examination (Fig. 1, Panels 1.1, 1.2). Whereas, a partial response of the other skin lesions located in the right mammary region is evident. At the start of the combined treatment, there were ulcerative lesions which healed (Fig. 1, Panels 1.3, 1.4).

Unfortunately, this treatment lasted for 4 months only due to the deterioration of the patient’s clinical condition. Dyspnea was, in fact, evident, at the start of the fifth cycle. The patient complained of coughing and further worsening of his ECOG PS. A chest radiography was done which was strongly suggestive of pneumonitis (Fig. 2a) then we interrupted treatment with everolimus and exemestane and we started him on systemic steroid therapy, bronchodilators and supplemental oxygen. A new X-ray was done 10 days after cessation of treatment and highlights an improvement in the pneumonitis (Fig. 2b).

a At the start of the fifth cycle dispnea was evident. A chest radiography was done which was strongly suggestive of pneumonitis then we interrupted treatment with everolimus exemestane and we started him on systemic therapy steroid, bronchodilators and supplemental oxygen. b A new chest radiography was taken 10 days after cessation of treatment and highlights an improvement in the pneumonitis

Despite this improvement in his breathing symptoms, his clinical condition worsened. He became even more cachectic and sadly expired a month later. Table 1 resumed patient’s medical history.

In 1996, the patient underwent genetic counseling and genetic testing which was negative for BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutation.

Conclusions

Although the hormonal environment in male patients differs from that in female patients, AIs may play a key role in the treatment of male BC patients since in men, 80% of circulating estrogens derived from peripheral aromatization of testicular and adrenal androgens, with direct production from the testes accounting for the remaining 20%. Several studies carried out in healthy men have demonstrated that administration of non-steroidal AIs causes a significant decrease in plasma estrogen. However, data about the impact of AIs on estrogen plasma levels in MBC patients and their clinical efficacy are still lacking [10–14]. Recently, Doyen et al. demonstrated that aromatase inhibition leads to a significant decrease of estrogen level in MBC patients [16]. However, baseline estrogen levels are higher in men than in postmenopausal women because of a higher level of peripheral androgens and AIs do not seem able to inhibit the testicular production of estrogen, which account for 20% of the circulating estrogen. In healthy men, AIs caused a significant increase of LH and FSH [17–19]. These results lead to hypothesize that suppression of estrogen production in male patients by monotherapy using AIs may be suboptimal respect to the combination of AIs with the analogue LH–releasing hormone [16, 20]. Aromatase inhibitors are widely used for treating metastatic male breast cancer patients but, in this setting, their use is not substantiated by prospective clinical trials, rather driven by supposed similarities existing with breast cancer in postmenopausal women [21].

BOLERO-2 trial results demonstrated that the combination of everolimus and exemestane increases the efficacy compared with exemestane in terms of progression-free survival (4–6 months) in a patient population of postmenopausal, hormone receptor positive, advanced breast cancer patients up to one prior chemotherapy treatment [15]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the second case of male breast cancer treated with everolimus. Recently, Kattan J reported the first case of a 74-year-old man who had relapsed after 4 years of adjuvant tamoxifen therapy. Eight subsequent cycles of vinorelbine and capecitabine produced a moderate partial response. Tamoxifen was reintroduced to maintain the outcome, whereas in an attempt to reverse hormone-resistance, tamoxifen and everolimus were combined [22].

Although heavily pretreated, our patient responded very well to endocrine therapy so, despite his poor clinical condition, we proposed a new endocrine line with exemestane and everolimus as an off label treatment ruling out the option of tamoxifen everolimus combination, because of his recent pulmonary thromboembolism.

Besides, today, it’s also uncertain if exemestane is the optimal treatment to adding with everolimus. Ongoing trials have been evaluated the role of everolimus to reverse hormone-resistance in combination with different endocrine agents as ER antagonist (e.g., Fulvestrant) or as monotherapy. On this basis, we are waiting for results of a phase II trial to evaluate the efficacy of everolimus as monotherapy in the treatment of women with ER+ metastatic BC [23].

In our experience, that is the case of a highly pretreated patient with very good response to endocrine therapy and who precociously stopped the everolimus plus exemestane treatment because of the development of pneumonitis. It has already been documented that about 15–20% of female BC patients treated with everolimus and exemestane combination have non-infectious pneumonitis. From BOLERO-2 trial results, approximately one-quarter of events (grade ≥2) occurred within the first 12 weeks (cumulative risk, 5%). Cumulative risks of pneumonitis (grade ≥2) in the EVE + EXE arm were 10 and 16% at 24 and 48 weeks, respectively. Among patients with grade 3 pneumonitis in the EVE + EXE arm, 80% experienced resolution to grade ≤1, typically following dose interruption/reduction, after a median of 3.8 weeks and in case administering systemic steroids, and supplemental oxygen if patient’s symptoms are moderate to severe [24–26]. The pulmonary toxicities incidence in patients affected by BC are similar to those affected by metastatic renal cell carcinoma and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors which are treated with everolimus respectively in 2nd/3th line and in case of unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic disease [26].

That is the case of long survival male BC patient with luminal B subtype and no BRCA mutations. Furthermore, our patient achieved higher PFS with endocrine therapy than chemotherapy creating the rationale for last line of treatment with everolimus and exemestane combination. He immediately reported an important clinical benefit, as it could be highlighted by the resolution of skin lesions after one month of treatment. Exemestane and everolimus combination offered a partial response with the severe adverse event pneumonitis leading to treatment interruption shortly before the patient expired.

Attending conclusive results from ongoing studies, the combination should not be used routinely in male metastatic BC patients. It might be taking into account for highly selected cases, as male patients with HR positive BC with good response and long time to progression to preceding endocrine lines and especially with very good performance status since the possible severe adverse events.

Abbreviations

- BC:

-

breast cancer

- MBC:

-

male breast cancer

- AIs:

-

aromatase inhibitors

- CT:

-

computed tomography

- TTP:

-

time to progression

- PR:

-

partial response

- SD:

-

stationarity of disease

- PD:

-

progression of disease

- LHRHa:

-

luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist

- ECOG-PS:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status

- CERM:

-

Ethics Committee of the Marche region

- BRCA:

-

BReast CAncer gene

- LH:

-

luteinizing hormone

- FSH:

-

follicle-stimulating hormone

- EVE:

-

everolimus

- EXE:

-

exemestane

References

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2014. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/webcontent/acspc-042151.pdf. Accessed 2 Sept 2014.

Giordano SH, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN. Breast cancer in men. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(8):678–87. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-137-8-200210150-00013.

White J, Kearins O, Dodwell D, Horgan K, Hanby AM, Speirs V. Male breast carcinoma: increased awareness needed. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13(5):219. doi:10.1186/bcr2930.

Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Forman D. Cancer incidence in five continents, CI5plus: IARC Cancer Base No. 9. 2014. http://ci5.iarc.fr. Accessed 19 Dec 2014.

Ferlay J SI, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. 2013. http://globocan.iarc.fr. Accessed 29 Jul 2014.

Scott-Conner CE, Jochimsen PR, Menck HR, Winchester DJ. An analysis of male and female breast cancer treatment and survival among demographically identical pairs of patients. Surgery. 1999;126:775–80. doi:10.1016/S0039-6060(99)70135-2.

Dabakuyo TS, Dialla O, Gentil J, Poillot ML, Roignot P, Cuisenier J, et al. Breast cancer in men in Cote d’Or (France): epidemiological characteristics, treatments and prognostic factors. Eur J Cancer Care. 2012;21:809–16. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2012.01365.x.

Speirs V, Shaaban AM. The rising incidence of male breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115(2):429–30. doi:10.1007/s10549-008-0053-y.

Giordano SH, Cohen D, Buzdar A, Perkins G, Hortobagyi GN. Breast carcinoma in men: a population-based study. Cancer. 2004;101:51–7. doi:10.1002/cncr.20312.

Giordano SH, Valero V, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN. Efficacy of anastrozole in male breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2002;25:235–7.

Italiano A, Largillier R, Marcy PY, Foa C, Ferrero JM, Hartmann MT, et al. Complete remission obtained with letrozole in a man with metastatic breast cancer. Rev Med Intern. 2004;25:323–4. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdp450.

Zabolotny BP, Zalai CV, Meterissian SH. Successful use of letrozole in male breast cancer: a case report and review of hormonal therapy for male breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2005;90(1):26–30. doi:10.1002/jso.20233.

Arriola E, Hui E, Dowsett M, Smith EI. Aromatase inhibitors and male breast cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2007;9:192–4. doi:10.1007/s12094-007-0034-3.

Steele N, Zekri J, Coleman R, Leonard R, Dunn K, Bowman A, et al. Exemestane in metastatic breast cancer: effective therapy after third-generation non-steroidal aromatase inhibitor failure. Breast. 2006;15:430–6. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2005.08.032.

Piccart M, Hortobagyi GN, Campone M, Pritchard KI, Lebrun F, Ito Y, et al. Everolimus plus exemestane for hormone-receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2-negative advanced breast cancer: overall survival results from BOLERO-2. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(12):2357–62. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdu456.

Doyen J, Italiano A, Largillier R, Ferrero JM, Fontana X, Thyss A. Aromatase inhibition in male breast cancer patients: biological and clinical implications. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1243–5. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdp450.

Bhatnagar AS, Müller P, Schenkel L, Trunet PF, Beh I, Schieweck K. Inhibition of estrogen biosynthesis and its consequences on gonadotrophin secretion in the male. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;41:437–43. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(92)90369-T.

Trunet PF, Mueller P, Bhatnagar AS, Dickes I, Monnet G, White G. Open dose-finding study of a new potent and selective nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor, CGS 20 267, in healthy male subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:319–23. doi:10.1210/jcem.77.2.8345034.

Mauras N, O’Brien KO, Klein KO, Hayes V. Estrogen suppression in males: metabolic effects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2370–7. doi:10.1210/jcem.85.7.6676.

Di Lauro L, Vici P, Del Medico P, Laudadio L, Tomao S, Giannarelli D, et al. Letrozole combined with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog for metastatic male breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;141(1):119–23. doi:10.1007/s10549-013-2675-y.

Maugeri-Saccà M, Barba M, Vici P, Pizzuti L, Sergi D, De Maria R, et al. Aromatase inhibitors for metastatic male breast cancer: molecular, endocrine, and clinical considerations. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;147(2):227–35. doi:10.1007/s10549-014-3087-3.

Kattan J, Kourie HR. The use of everolimus to reverse tamoxifen resistance in men with metastatic breast cancer: a case report. Invest New Drugs. 2014;32(5):1046–7. doi:10.1007/s10637-014-0133-2.

Bent E, Guy HMJ, Sara A, Richard HH, Taran De Boer T, Shmoud T et al. BOLERO-6: Phase II study of everolimus plus exemestane versus everolimus or capecitabine monotherapy in HR+, HER2− advanced breast cancer. 2013 ASCO Annual Meeting. J Clin Oncol 31, 2013 (suppl; abstr TPS660). https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01783444.

Peterson ME. Management of adverse events in patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer treated with everolimus: observations from a phase III clinical trial. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(8):2341–9. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-1826-3.

Iacovelli R, Palazzo A, Mezi S, Morano F, Naso G, Cortesi E. Incidence and risk of pulmonary toxicity in patients treated with mTOR inhibitors for malignancy. A meta-analysis of published trials. Acta Oncol. 2012;51(7):873–9. doi:10.3109/0284186X.2012.705019.

Verzoni E, Pusceddu S, Buzzoni R, Garanzini E, Damato A, Biondani P, et al. Safety profile and treatment response of everolimus in different solid tumors: an observational study. Future Oncol. 2014;10(9):1611–7. doi:10.2217/fon.14.31.

Authors’ contributions

ZB, MP conceived and designed the study. NB, AP were involved in data acquisition. MDL carried out the immunoassays, RB, SC were involved in interpretation of the data. ZB, MP drafted the manuscript. ZB takes final responsibility. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Stefano Cascinu for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. The authors are grateful to Paul Bowerbank for his help in reviewing the English of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests, neither financial and non-financial competing interests.

Availability of data and material

The medical record was reviewed to find data on patient’s medical history. Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or used during the current study.

Consent for publication

Awritten informed consent was obtained from the patient’s next of kin for publication of this Case Report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by Editor in Chief of this journal.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

According to our country’s legislation, since it was a retrospective study, with no direct patient involvement, the ethical approval and patients consent for the study were not required (Official Gazette No. 72 of March 26, 2012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ballatore, Z., Pistelli, M., Battelli, N. et al. Everolimus and exemestane in long survival hormone receptor positive male breast cancer: case report. BMC Res Notes 9, 497 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-016-2301-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-016-2301-2