Abstract

Introduction

Mutations in the TNFRSF1A gene, encoding tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNF-R1), are associated with the autosomal dominant autoinflammatory disorder, called TNF receptor associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS). TRAPS is clinically characterized by recurrent episodes of long-lasting fever and systemic inflammation. A novel mutation (c.262 T > C; S59P) in the TNFRSF1A gene at residue 88 of the mature protein was recently identified in our laboratory in an adult TRAPS patient. The aim of this study was to functionally characterize this novel TNFRSF1A mutation evaluating its effects on the TNF-R1-associated signaling pathways, firstly NF-κB, under particular conditions and comparing the results with suitable control mutations.

Methods

HEK-293 cell line was transfected with pCMV6-AC construct expressing wild-type (WT) or c.262 T > C (S59P), c.362G > A (R92Q), c.236C > T (T50M) TNFRSF1A mutants. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were instead isolated from two TRAPS patients carrying S59P and R92Q mutations and from five healthy subjects. Both transfected HEK-293 and PBMCs were stimulated with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) or interleukin 1β (IL-1β) to evaluate the expression of TNF-R1, the activation of TNF-R1-associated downstream pathways and the pro-inflammatory cytokines by means of immunofluorescent assay, array-based technique, immunoblotting and immunometric assay, respectively.

Results

TNF induced cytoplasmic accumulation of TNF-R1 in all mutant cells. Furthermore, all mutants presented a particular set of active TNF-R1 downstream pathways. S59P constitutively activated IL-1β, MAPK and SRC/JAK/STAT3 pathways and inhibited apoptosis. Also, NF-κB pathway involvement was demonstrated in vitro by the enhancement of p-IκB-α and p65 nuclear subunit of NF-κB expression in all mutants in the presence of TNF or IL-1β stimulation. These in vitro results correlated with patients’ data from PBMCs. Concerning the pro-inflammatory cytokines secretion, mainly IL-1β induced a significant and persistent enhancement of IL-6 and IL-8 in PBMCs carrying the S59P mutation.

Conclusions

The novel S59P mutation leads to defective cellular trafficking and to constitutive activation of TNF-R1. This mutation also determines constitutive activation of the IL-1R pathway, inhibition of apoptosis and enhanced and persistent NF-κB activation and cytokine secretion in response to IL-1β stimulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS; OMIM 142680) is the second most common inherited autosomal dominant autoinflammatory disease [1]. It is caused by mutations in the TNFRSF1A gene located on chromosome 12p13 and encodes the 55 kDa receptor for tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNF-R1). The disease is clinically characterized by periodic fever, abdominal pain, skin lesions, conjunctivitis, myalgia and pericarditis. Disease onset generally occurs in early childhood but it can present in adults, and inflammatory attacks can last several weeks. The most severe complication is AA-type serum amyloidosis, which can lead to renal impairment and failure [2-4].

The TNF-R1 presents an extracellular domain involved in ligand binding, a transmembrane domain involved in receptor solubilization and an intracellular region where death domains (DD) are involved in signal transduction [5,6]. The binding of TNF to TNF-R1 causes recruitment of several intracellular adaptor proteins leading to downstream signaling events that activate the inflammatory (complex I) and apoptotic (complex II) processes. Complex I activation prevails and leads to NF-κB activation and transcription of anti-apoptotic and pro-inflammatory genes [7-27].

Almost all known mutations associated with TRAPS are characterized by the replacement of amino acids in the extracellular domain of the TNF-R1. More than 100 mutations are registered in the INFEVERS database [18], which are discerned in high-penetrance and low-penetrance mutations. The former affects mainly the cysteine residues in the extracellular cysteine-rich domains (CRDs) involved in disulfide bond formation and extracellular TNF-R1 folding and function. These mutations are associated with the most severe clinical phenotype, in which there is high risk of AA-type serum amyloidosis. Low-penetrance mutations include genetic variants that introduce or remove proline residues (such as P46L, L57P, S86P, and R92P) or affect hydrogen bond stabilization of the receptor (such as T50M) [19]. These mutations affect the secondary structure of TNF-R1 and are associated with a typical TRAPS phenotype, but in these cases the risk of AA-type serum amyloidosis is low [20-22]. Other low-penetrance TNFRSF1A variations, such as R92Q, are associated with milder clinical manifestations, suggesting that in these cases other genetic and/or environmental factors can play a role in the disease’s pathogenesis [20-26]. The high penetrance TNFRSF1A mutations involving the cysteine residues (C29F, C30R/S, C33G/Y, Y38C, C52F, C55S, C70R/Y, and C88R/Y) are less frequent (34%) than those with a low penetrance (76%), the latter being mainly represented by the T50M (15.8%) and R92Q (28.9%) variants [21].

We recently identified a novel mutation in the TNFRSF1A gene (exon 3, c.262 T > C) in an adult TRAPS patient. Clinically, the patient had fever, leukocytosis, recurrent bronchopneumonia, palpebral ptosis, episodes of arthralgia, myalgia and intermittent erythematosus skin lesions of the limbs and trunk. His serum immunoglobulin D (IgD), immunoglobulin A (IgA) and serum amyloid A protein (SAA) levels were elevated. While traditional therapy with the TNF inhibitor etanercept was unsuccessful in this patient, alternative therapy with the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) anakinra promptly induced disease remission. The identified new genetic variant results in a proline for serine amino acid substitution (S59P or p.Ser88Pro) at residue 88, localized in the extracellular domain of the mature protein. This variant might be included in the above-described category of mutations that introduce proline residues. The distinctive cyclic structure of proline’s side chain gives it an exceptional conformational rigidity, interfering in peptide bond formation with other amino acids and affecting the secondary structure of the protein [27].

Overall, the molecular pathogenesis of TRAPS is not yet completely understood. The change in secondary structure might cause defective TNF-R1 trafficking, altered ligand binding affinity, reduced activation-induced shedding and impaired cell signaling. Based on these premises, several hypotheses have been formulated: the shedding hypothesis [1,28,29], the misfolding hypothesis [30-33], the NF-κB hypothesis [34,35] and the recent ROS hypothesis [36,37].

Since the patient carrying the S59P mutation was responsive to IL-1Ra but not to anti-TNF therapy, the aim of this study was to verify whether this mutation modifies the cell signaling, in particular in the NF-κB pathway, after TNF and IL-1β stimulation.

Methods

Wild-type and mutant TNFRSF1A cDNA vectors

We purchased the vector pCMV6-AC (OriGene Technologies, Inc. Rockville, MD, USA) containing wild-type (WT) TNFRSF1A cDNA ready for transfection. Three new constructs containing three mutant TNFRSF1A - cDNA (c.262 T > C (S59P); c.362G > A (R92Q) and c.236C > T (T50M)) were obtained using site-direct mutagenesis, and the following mutagenic primers were used: TNFRFS59P: 5′AGTGTGAGAGCGGCCCCTTCACCGCTTCAG3′; TNFRFR92Q: 5′ CTTCTTGCACAGTGGACCAGGACACCGTGTGTGGCTG 3′; TNFRRT50M: 5′ CTCACACTCCCTGCAGTCCATATCCTGCCCCGGGCCTGG 3′.

All the products were sequenced along the full length of the TNFRSF1A coding region to ensure that only the desired mutations were introduced. Plasmid isolation from bacterial culture was carried out using the PureYield Plasmid Maxiprep System (Promega, Milano, Italy).

Stable transfection of cell line HEK-293

Human embryonic kidney (HEK-293) cell line was used for the transfection. This cell line expressed moderate levels of endogenous TNF receptors and exhibited high transfection efficiency. A total of 4 μg of plasmid were incubated with 10 μL Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen, San Giuliano Milanese, Italy) in 500 μL serum and antibiotic-free DMEM (Invitrogen, San Giuliano Milanese, Italy) for 20 minutes at 25°C. The reagent was then directly added to each cell culture well (200,000 cells) in a 6-well plate format. After 6 hours, media were replaced with fresh serum-supplemented media, and the cells were maintained at 37°C for the subsequent 24 hours. To obtain stable transformed cells, they were treated with 0.8 mg/mL Geneticin® (G418) (Invitrogen, San Giuliano Milanese, Italy) for 15 days.

Patients

Two TRAPS patients were referred to the Rheumatology Unit of University of Padova and were studied: one carrying the S59P mutation and the other the R92Q mutation. Moreover, 5 subjects (3 males and 2 females, age range: 30 to 50 years) without any variants in the TNFRSF1A gene were studied as healthy controls. At the time the study was carried out, the TRAPS patients were on anakinra and infliximab therapy, respectively, and did not present inflammatory symptoms. The study protocol was approved by our institutional review board (Comitato Etico per la Sperimentazione, Azienda Ospedaliera di Padova, protocol number: 0060237) and the patients gave their fully informed written consent to participate in the study. The clinical characteristics of the enrolled TRAPS patients are detailed in Table 1.

According to our medical file, which includes 300 Italian patients with a clinical suspect of TRAPS, none carried the T50M mutation.

TNFRSF1A mutation detection

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using the standard method (MagNA Pure System, Roche S.p.A., Monza, Italy). After amplification by polymerase chain reaction with primers as described by D’Osualdo et al. [38], sequencing of the TNFRSF1A gene was performed using the automatic sequencer 3130ABI PRISM Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). Chromatograms were analyzed with Chromas Lite 2.01 software (Technelysium Pty Ltd., South Brisbane, QLD, Australia).

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolation and culture

Blood (20 mL) was collected with EDTA K3 test tubes and was processed within 2 hours of sampling to isolate mononuclear cells by gradient centrifugation (Histopaque®-1077, Sigma-Aldrich, Milano, Italy). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were suspended in culture medium (Roswell Park Memorial Institute Medium (RPMI) supplemented with 0.1% gentamicin, 10% FCS and 1% glutamine; Invitrogen, San Giuliano Milanese, Italy) and incubated at 37°C for 24 and 72 hours prior to experimental manipulation to prevent any experimental anomalies arising as a consequence of therapy.

Immunofluorescence

HEK-293 transfected with WT or mutant TNFRSF1A were seeded onto slides (3 × 105) and maintained in culture for 24 hours. Cells were stimulated with or without TNF (60 ng/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, Milano, Italy) for 1 hour to induce TNF receptor expression. They were then washed in PBS 1X and fixed in 4% formaldehyde fixative (Sigma-Aldrich, Milano, Italy) for 10 minutes at room temperature.

Dual indirect staining was performed using primary monoclonal mouse antibody anti-human CRI/TNF-R1-PE (R&D Systems Inc.) Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA and the appropriate Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen, San Giuliano Milanese, Italy). The cells were washed in PBS 1X, incubated with NH4Cl (50 mM) for 10 minutes and with Triton X-100 (0.1%) for 5 minutes. The cells were then washed in PBS 1X and incubated with PBS with BSA (1%) for 45 minutes. The first primary antibody was added to the cells and incubated for one hour at room temperature in the dark. Cells were then washed three to four times in PBS 1X. The secondary antibody was added to the cells and incubated for one hour at room temperature in the dark. Confocal microscopy was performed using a Radiance 2000 confocal laser scanning microscope (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Milano, Italy).

Reverse phase protein array analysis

Reverse phase protein array (RPPA) analysis was performed using a procedure previously optimized and validated [39]. Briefly, cell lysates were solubilized in 4× SDS loading buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, Milano, Italy) and heated for 5 minutes at 95°C. Samples were spotted in duplicate onto nitrocellulose-coated glass slides (Grace Bio-labs Bend, Oregon, USA) using a microarraying robot (MicroGrid 610, Digilab, Marlborough, MA, USA). The printed slides were blocked and incubated overnight at 4°C with shaking with the specific primary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Additional file 1 shows in more detail the list of primary antibodies used for RPPA analysis with their respective signaling pathways. β-actin was included as a housekeeping protein to control protein loading. After incubation with infrared secondary antibodies (800 CW LI-COR anti-rabbit antibody and 700 CW LI-COR anti-mouse antibody) Lincoln, Nebraska, USA, the slides were scanned with a Licor Odyssey scanner (LI-COR, Biosciences Lincoln, Nebraska, USA) at 21 μm resolution at 700 and 800 nm. The fluorescent data were processed with GenePix Pro-6 Microarray Image Analysis software (Molecular Services Inc. Sunnyvale, California, USA). Protein signals were determined with background subtraction and normalization to the internal housekeeping targets using an Reverse-phase protein analyzer [40].

Immunoblotting

WT or mutant TNFRSF1A HEK-293 and PBMCs were seeded (5 × 106) onto Petri dishes (diameter: 10 cm) and maintained in a laboratory culture for 24 hours. Cells were incubated with and without TNF (6 ng/mL) or with IL-1β (1 ng/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, Milano, Italy) for 10 minutes to activate signaling pathways. Following stimulation, the Petri dishes were immediately transferred to an ice bath, and the cells were washed twice with cold PBS, resuspended in 100 μL of cold lysis buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 50 mM NaF, 10 mM Na4P2O7, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 10% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, Milano, Italy)). Lysates were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 14,000 rpm at 4°C and the supernatants were collected. The pellets were resuspended in a nuclear extraction buffer mix (Thermo Scientific Inc., Rockford, USA) and proceeded to generate nuclear extracts, as described in the manufacturer’s instructions. Total cytosolic and nuclear proteins were measured using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Milano, Italy).

For each sample, 40 μg proteins were electrophoresed using a 4-12% NuPAGE® Novex Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE Gel or 3-8% NuPAGE® Novex Tris-Acetate SDS-PAGE Gel (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Monza, Italy), and were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (iBlot® Transfer Stack, Invitrogen Life Technologies, Monza, Italy) using iBlot® Dry Blotting System (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Monza, Italy). The membranes were incubated for 1 hour in blocking buffer (5% low-fat powder milk resuspended in PBS-T (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20)). They were then incubated overnight with the primary antibodies (anti-phospho IkB-α (Ser32) and anti-phospho-NF-κB subunit p65 (Ser536) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) and anti-β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, Milano, Italy)) diluted 1:5,000 (β-actin) or 1:3,000 (all the others) in blocking buffer. The blots were washed three times in PBS-T for 15 minutes and incubated for 1 hour with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). The blots were washed three times in PBS-T for 15 minutes and developed with the ECL Advance Western Blot Detection Kit (GE Healthcare Technologies, Milano, Italy).

Cytokine assay

Cells transfected with WT or mutant TNFRSF1A and PBMCs cultured for 24 and 72 hours were incubated at 200 × 103/mL in 24-well plates in culture medium. The cells were stimulated with and without TNF (6 ng/mL) or IL-1β (1 ng/mL) or lipopolysaccharide ((LPS) 1 μg/mL) as positive controls (PC) for four hours. Supernatants were collected, centrifuged to remove cells and debris and stored at −80°C. IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF cytokine analysis was performed using an immunometric assay (IMMULITE-Siemens, Milano, Italy).

Statistical analysis

Two sets of data were analyzed using an independent sample t test. The data of more than two groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni’s test for pairwise comparisons. The statistical software Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 9) was used. All experimental data were obtained from a series of independent experiments (n = 3).

Results

S59P is a novel TRAPS-associated mutation

Based on the clinical suspect of TRAPS, a 67-year-old Italian male (clinical characteristics detailed in Table 1) was sent to our department. By performing TNFRSF1A sequencing, this patient was demonstrated to carry in heterozygosis a mutation which has never been previously described (Figure 1, panel A). This single-base mutation (c.262 T > C), located in exon 3, results in a proline for serine amino acid substitution (S59P) at residue 88 of the mature protein. We studied another TRAPS patient (clinical characteristics also detailed in Table 1) who carried in heterozygosis the common single-base mutation (c.362G > A) in exon 4 (Figure 1, panel B), resulting in an arginine for glutamine amino acid substitution (R92Q) at residue 121 of the mature protein.

DNA sequence electropherograms of TNFRSF1A. A: electropherogram of the heterozygous single-base mutation (c.262 T > C) in exon 3, resulting in a Pro for Ser amino acid substitution. B: electropherogram of the heterozygous single-base mutation (c.362G > A) in exon 4, resulting in an Arg for Gln amino acid substitution.

Different TNFRSF1A mutants activate specific TNF-R1 downstream signaling pathways

To ascertain whether the novel S59P mutation is causative of an altered TNF-R1 expression and function, in vitro experiments were performed using the HEK-293 cell line transfected with a plasmid expression vector carrying the S59P-mutated TNFRSF1A. For comparison, the same HEK-293 cells were transfected with the WT TNFRSF1A and the R92Q and T50M TNFRSF1A mutants.

We first analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence TNF-R1 expression in unstimulated (Figure 2, left panels) and TNF-stimulated (Figure 2, right panels) WT, S59P, R92Q and T50M HEK-293 transfected cells. In unstimulated WT cells (Figure 2A), the TNF-R1 was weakly expressed in the cytosol. A similar pattern was observed in S59P (Figure 2B) and R92Q (Figure 2C) HEK-293 mutant cells, while in the presence of T50M mutation a more intense cytosolic fluorescence with a granular-type pattern could be identified (Figure 2D). TNF at the dosage of 60 ng/mL caused an enhanced expression and granularity of cytosolic TNF-R1 not only in WT (Figure 2A1), but also in all mutant HEK-293 cells. Although a clear differentiation of cell surface from intracellular localizations was not possible, an enforced fluorescence with granular pattern outlining cell shape was observed in all TNF-stimulated cells.

TNF-R1 expression in cell lines. Confocal microscopy analysis of anti-TNF-R1 (green) immunofluorescent staining. HEK-293 cells transfected with wild-type (WT) or mutant TNFRSF1A remained unstimulated or they were stimulated with 60 ng/mL TNF. Panel A (without TNF) and A1 (with TNF) are WT TNFRSF1A HEK-293. Panel B (without TNF) and B1 (with TNF) are S59P TNFRSF1A HEK-293. Panel C (without TNF) and C1 (with TNF) are R92Q TNFRSF1A HEK-293. Panel D (without TNF) and D1 (with TNF) are T50M TNFRSF1A HEK-293.

We then verified whether the TNFRSF1A mutations are associated with a constitutive activation of the TNF-R1 or other signaling pathways, and whether these mutations modify intracellular signaling in response to TNF and IL-1β, taking into account that the patient carrying the S59P mutation had a complete clinical response when treated with IL-1Ra but not with anti-TNF therapy. RPPA with unstimulated and TNF- or IL-1β-stimulated cells were performed and the following pathways analyzed: TNF-R1, MAP kinase, c-Jun, IL-1β, NF-κB, ERK, inflammasome, PI3/AKT, SRC/JAK/STAT and apoptosis. In Figure 3 the percentage changes in fluorescence intensity relative to untreated WT HEK-293 cells are shown; for any studied signaling pathway, a key component molecule is shown. Additional file 2 shows in more detail all remaining RPPA data for any studied signaling pathway. A constitutive activation of the TNF-R1 and inflammasome signaling pathways, characterized by increased A20/TNFAIP3, p-NF-κB and caspase 1, was associated with the T50M, not with the S59P or R92Q mutations. The newly identified S59P mutation was associated with the constitutive activation of IL-1β (pIRAK), MAPK (p38MAPK) and SRC/JAK/STAT3 (SOCS3) pathways. In R92Q mutants, the constitutive activation of SRC/JAK/STAT3 was associated with the inhibition of PI3K/AKT, ERK, c-Jun and inflammasome pathways. Apoptosis (BCL-2) was constitutively inhibited in all mutants. TNF and IL-1β activated the TNF receptor pathway and inhibited apoptosis in WT cells. The TNF-R1 pathway was not activated by TNF or IL-1β in mutant cells, nor was it even inhibited by IL-1β in the T50M mutant. Differently from the R92Q and T50M mutants, the S59P mutation did not abolish the anti-apoptotic effects of TNF and IL-1β.

Reverse phase protein array (RPPA) results. In each panel the percentage changes in fluorescence intensity relative to untreated wild-type (WT) HEK-293 cells are shown. For any signaling pathway, a key component molecule is shown. Bonferroni’s test for pairwise comparisons: *P <0.05 with respect to untreated WT HEK-293 cells; #P <0.05 with respect to its own untreated control.

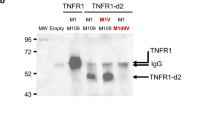

TNFRSF1A mutants activate NF-κB pathway in transfected cells and in peripheral blood mononuclear cells

We then ascertained in more depth whether a different response to TNF and IL-1β in terms of activation or inhibition of the NF-κB pathway, depends on TNFRSF1A mutations. This objective took into consideration that NF-κB is one of the main TNF-R1 downstream signaling pathways [41], and that both pathways were differently affected by S59P, R92Q and T50M mutations (shown in RPPA results). The effects of TNF and IL-1β on two key NF-κB signaling molecules, p-IκB-α (Ser32) and p65 component (p-NF-κB (Ser536)), were assessed by Western blot analysis in WT, S59P, R92Q and T50M HEK-293, and in PBMCs obtained from TRAPS patients and controls.

Figure 4 shows Western blot results of transfected HEK-293 cell lines. TNF and IL-1β reduced the phosphorylation of IκB-α (p-IκB-α Ser32) in WT cells, while the opposite was found when they were added to S59P and T50M mutant cells. In R92Q cells, little if any variation in IκB-α phosphorylation was seen. The Western blot analysis of the p65 component in isolated nuclei (p-NF-κB Ser536) showed that TNF and IL-1β did not activate p65 in WT HEK-293 cells. By contrast, this component was phosphorylated by TNF in all mutants, and by IL-1β in S59P and R92Q, but not T50M mutants. Confirming RPPA findings, p65 was constitutively activated in the T50M HEK-293, and this activation was sustained by TNF and partly counteracted by IL-1β.

Effects of TNF and IL-1β on the NF-κB pathway in cell lines. Wild-type (WT) and mutant TNFRSF1A HEK-293 unstimulated (NC) or stimulated for 10 minutes or with TNF (6 ng/mL) or IL-1β (1 ng/mL). Western blot shows p-IκBα (Ser32) and p65 subunit of NF-κB (Ser536) and the corresponding β-actin, used as a control. The histograms show semi-quantification of band intensities after normalization against the negative control (100%) (OD; Image J software, version 1.47 NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). Columns indicate percent values.

Figure 5 shows Western blot analysis of p-IκB-α (p-IκB-α Ser32) and of nuclear p65 component (p-NF-κB Ser536) in control and TRAPS PBMCs kept in culture for 24 hours unstimulated or stimulated with TNF and IL-1β. In basal conditions IκB-α phosphorylation was higher in TRAPS with respect to control PBMCs. In both control and TRAPS patients TNF reduced IκB-α phosphorylation. IL-1b reduced the phosphorylation of IkB-a in control PBMCs, while enhnacing it in TRAPS PBMCs. In the same experimental conditions, p65 activity in isolated nuclei was constitutively elevated only in S59P TRAPS PBMCs. Both TNF and IL-1β induced the p65 phosphorylation in controls and TRAPS PBMCs.

NF-κB pathway in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Control (wild-type (WT)) and TRAPS peripheral blood mononuclear cells unstimulated or stimulated for 10 minutes with TNF (6 ng/mL) or IL-1β (1 ng/mL). Western blot shows p-IκBα (Ser32) and p65 subunit of NF-κB (Ser536) and the corresponding β-actin, used as control. The histograms show semi-quantification of band intensities after normalization against the negative control (100%) (OD; Image J software, version 1.47 NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). Columns indicate percent values.

TNFRSF1A mutants increase pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion in transfected cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells

We then examined if NF-κB activation might be functionally linked to the secretion of inflammatory cytokines. Levels of IL-8 were measured in WT, S59P, R92Q and T50M HEK-293 supernatants. Levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF were measured in PBMCs supernatants. Cells were incubated in fresh media with or without TNF (6 ng/mL), IL-1β (1 ng/mL) or LPS (1 μg/mL) as a positive control for 4 hours.

Non-stimulated S59P, R92Q and T50M HEK-293 released higher levels of IL-8 compared to WT cells (t = −29, P <0.0001; t = −89.2, P <0.0001; t = −8.6, P <0.001) (Figure 6). TNF induced a significantly higher IL-8 secretion in S59P (t = −5.1, P <0.005) and R92Q (t = −52.3, P <0.0001), not in T50M (t = −0.8; p: not significant) mutants, with respect to WT HEK-293 cells.

In all PBMCs (Figure 7, upper panels) a 24-hour culture of LPS induced significantly higher IL-1β (control: F = 35, P <0.0001; S59P: F = 31, P <0.0001; R92Q: F = 153, P <0.0001), IL-6 (control: F = 44, P <0.0001; S59P: F = 4,046, P <0.0001; R92Q: F = 661, P <0.0001), IL-8 (control: F = 45, P <0.0001; S59P: F = 808, P <0.0001; R92Q: F = 5,755, P <0.0001) and TNF (control: F = 198, P <0.0001; S59P: F = 448, P <0.0001; R92Q: F = 53, P <0.0001) secretion. Both TNF and IL-1β induced significantly higher IL-8 release in the control with respect to the TRAPS PBMCs (TNF: F = 29, P <0.0001; IL-1β: F = 15, P <0.0001).

Proinflammatory cytokine response in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Cytokine levels (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF) in control (WW) and TRAPS peripheral blood mononuclear cells maintained in culture for 24 (panel A) and 72 hours (panel B) and unstimulated or stimulated for 4 hours with LPS (1 μg/mL) (positive control), TNF (6 ng/mL) or IL-1β (1 ng/mL). Columns represent mean values ± SEM. *P <0.0001; °P <0.05; °°P <0.001 with respect to WW.

In a 72-hour culture (Figure 7, lower panels), LPS no longer affected IL-1β secretion in control PBMCs, but it continued to induce IL-1β secretion in the S59P (F = 7.55, P = 0.012) and R92Q (F = 20.8, P <0.0001) TRAPS PBMCs. LPS maintained its stimulatory effect at 72 hours on IL-6 (control: F = 179, P <0.0001; S59P: F = 1055, P <0.0001; R92Q: F = 489, P <0.0001), IL-8 (control: F = 224, P <0.0001; S59P: F = 167, P <0.0001; R92Q: F = 1042, P <0.0001) and TNF (control: F = 323, P <0.0001; S59P: F = 507, P <0.0001; R92Q: F = 466, P <0.0001) secretion. TNF-stimulated IL-8 secretion was significantly higher in the S59P and R92Q TRAPS than in the control PBMCs (F = 24, P <0.0001). IL-1β stimulus maintained both IL-6 and IL-8 secretion higher in the S59P and R92Q TRAPS than in the control PBMCs (F = 11, P <0.005; F = 322, P <0.0001) (Figure 7, lower panels).

Discussion

Mutations in the TNFRSF1A gene cause the autosomal-dominant, with incomplete penetrance, autoinflammatory disorder TRAPS. Mutations located in the CRDs region of the receptor are highly penetrant and associated with the most severe clinical phenotypes. However, these mutations are less frequent than those involving extracellular non-cysteine residues, with R92Q and T50M being the most common [1]. The cellular mechanisms underlying the pathophysiology of TRAPS are complex and depend on the mutation involved, which then defines some of its clinical features [21,42].

We identified a novel TNFRSF1A mutation in an adult patient diagnosed as having TRAPS. This patient had a variety of clinical manifestations, some of which were commonly associated with TRAPS (recurrent episodes of fever, myalgia and erythematosus skin lesions), and others which are reported less frequently (pericarditis and pneumonia) [43]. Sequencing of the TNFRSF1A gene was performed in this patient after about 18 years of recurrent episodes of bronchopneumonia, fever and other systemic signs of inflammation with an incomplete response to steroid treatment. This long lag time between disease onset and diagnosis depends on the lag time between disease onset and TRAPS first description [1]. The identified novel mutation was located in exon 3 and leads to the substitution of proline for serine at residue 88 of TNF-R1 (S59P).

Any amino acid substitution in the ectodomain of TNF-R1 might affect its physiology, including membranal expression levels, three-dimensional receptor folding and stimulus-dependent or independent activation. The novel S59P mutation determines the presence in the TNF-R1 of one more proline residue, which might interfere with three-dimensional receptor folding, since the distinctive cyclic structure of proline’s side chain gives it an exceptional conformational rigidity and might cause a bend in the receptor’s secondary amino acid structure [27]. These structural consequences might subsequently cause an aberrant behaviour of the receptor, including ligand independent gain-of-function, which underlies TRAPS pathophysiology.

To understand the functional features of this novel S59P mutation, we set out to compare it with two frequent mutations that are well known in the literature: the R92Q and T50M mutations [20-23,31-33,38,44,45]. These two mutations were chosen in view of several considerations: neither involves cysteine residues, the R92Q mutation is associated with a variable phenotype [23], and the T50M mutation is associated with a typical TRAPS phenotype [21].

As it is difficult to study the pathophysiologic mechanisms of TRAPS in the patients themselves, we employed an in vitro model and only the noteworthy results were examined using the patients’ cells. We first focused on the expression of TNF-R1 by immunofluorescence and found that this receptor is homogeneously distributed in the cytosol of WT cells. S59P and R92Q mutations did not significantly modify this pattern, while T50M caused an enhanced cytosolic TNF-R1 expression with a granular appearance. These results are supported by previous data from Rebelo et al. [32], who showed by flow cytometry that the WT and R92Q TNF-R1 have a significant cell surface expression, with a proportion being intracellular, whereas the T50M is almost completely retained in the cytoplasm. Based on the pattern of S59P expression, we might suggest that this novel mutation, similarly to R92Q and differently from T50M, does not promote intracellular retention of TNF-R1.

We then verified whether the exposure of cells to the TNF-R1 cognate ligand TNF exerts a mutation-dependent effect on receptor expression. In WT, S59P and R92Q mutant cells, TNF caused an enforced expression of the TNF-R1 mainly in the cytosol but also at the cell membrane, while in T50M mutant cells TNF induced an enforced expression of cytoplasmic aggregates. It might be suggested that S59P, similarly to the R92Q mutation, does not alter TNF-R1 trafficking from the cytoplasm to the surface membrane, while the T50M mutation causes a misfolded protein that overloads, leading to the formation of aggregates in the cytosol [32,45].

The pivotal role of an altered TNF receptor in TRAPS pathophysiology supports traditional therapy with etanercept, a fusion molecule of TNF-R2/FcIg [21,25,36], or with other anti-TNF agents such as infliximab, a monoclonal anti-TNF antibody; however, in most cases these therapies were shown to be only partially efficacious [46,47]. Therapy with anakinra, a recombinant interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, has recently proven to be a promising therapeutic alternative, preventing short-term disease relapse even in etanercept-resistant patients [33,48-50]. The success of this therapeutic approach, also recorded in our S59P TRAPS patient, might be due to increased IL-1β secretion for impaired autophagy [51], but also to the interactions occurring between IL-1 and TNF-R1 signaling [52]. TNF-R1 trimerizes before binding to TNF trimer, which induces TRADD-dependent and independent activation of several downstream signaling pathways, including the NF-κB, apoptosis, JNK, c-Jun, p38-MAPK and ERK [53]. IL-1β signaling is initiated with recruitment of MyD88 to the Toll-IL-1 receptor domain, followed by the phosphorylation of several kinases and activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway [49].

By studying all the above TNF-R1 signaling pathways and the IL-1 pathway in WT and mutant cells with a comprehensive RPPA approach, we demonstrated that in the presence of T50M, not S59P or R92Q mutations, TNF-R1, NF-κB and caspase 1 are constitutively activated. In agreement with the hypothesis that a possible association between TNF-R1 mutation and IL-1 signaling exists, constitutively activated IRAK and TAK proteins, involved in the IL-1 signaling pathway, were observed in cells carrying the S59P mutation. In R92Q cells we observed an attenuation of NF-κB, c-Jun, ERK, Akt, and inflammasome pathways and an increase in suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) protein 3, which attenuates the intensity and/or duration of a cell’s response to a diverse range of extracellular stimuli by suppressing the signal transduction processes. These findings indicate that any TNFRSF1A mutant differently affects the pro-inflammatory signaling pathways downstream of TNF-R1: the T50M mutant activates TNF-R1 pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, the novel identified S59P mutant activates IL-1 signaling and the R92Q mutant inhibits, not activates, TRADD-dependent signaling. A common feature of all studied TNFRSF1A mutants was the constitutive inhibition of apoptosis by increased inhibition of BCL-2 and BAD. Considering that the molecular pathogenetic mechanisms proposed for TRAPS include defective autophagy, ROS production, defective apoptosis and enhanced activation of NF-κB, our results suggest that a defective apoptosis is a common feature of different TNFRSF1A mutations, and that their differences in causing more or less severe forms of disease are probably related to their ability in sustaining ligand-dependent and independent NF-κB activation and inflammation.

For this reason the NF-κB pathway was studied in more detail in our experimental setting. The activated TNF receptor triggers a set of cascade events, including IKK complex activation, phosphorylation and IκB-α degradation, and activation and nuclear translocation of the NF-κB complex that in turn modulates the expression of a sequence of pro-inflammatory genes [10-17,26]. By RPPA analysis, NF-κB was shown to be activated both constitutively and after exposure to TNF and IL-1β in the T50M mutant. Western blot analysis confirmed that TNF and IL-1β induced the phosphorylation of IκB-α, which was higher and more persistent in T50M and S59P than in the WT TNFRSF1A cells. This phenomenon could be explained by the combined TNF-independent autoactivation of the mutated receptor and by the TNF-dependent activation of the WT receptor, since both receptors are present in these heterozygous cells. The IκB-α downstream signaling involves the p65 subunit, which plays an important role in protecting from apoptosis and innate immunity [13,54]. Confirming reports by Yousaf et al. on T50K [30] and of Churchman et al. on T50M [55], we found that the p65 subunit was constitutively active in the T50M TNFRSF1A cells and, using Western blot analysis (see Figure 4), we found that TNF induced a higher phosphorylation of the nuclear p65 subunit in the mutated rather than the WT TNFRSF1A cells. The constitutive and stimulus-dependent accumulation of p65 in the nucleus might confer insensitivity to apoptosis and keep the cells in a hyper-inflammatory state. Findings in an in vitro model correlated with results obtained from the PBMCs of TRAPS patients. The NF-κB pathway was constitutively activated and upregulated by inflammatory stimuli in the presence of TRAPS-associated mutations. IL-1β supported the significance of IκB-α phosphorylation and NF-κB activation in S59P TRAPS PBMCs.

NF-κB activation leads to pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion [11,13,14]. We investigated this phenomenon by measuring IL-8 in transfected cells and IL-8, IL-6, TNF and IL-1β in PBMCs from the S59P and R92Q TRAPS patients. A limitation of our study is that there was no patient with the T50M mutation because it was never found in our series of TRAPS patients, and this prevents from comparing accurately the results obtained with the other variants. TNF induced a significant increased release of IL-8 in R92Q and in S59P TNFRSF1A cells. This finding is in agreement with results described by Nedjai et al. [35] and was supported by the clinical data: IL-1β induced a significantly higher and persistent IL-6 and IL-8 secretion in the S59P TRAPS PBMCs and IL-6 secretion in the R92Q TRAPS PBMCs, which were maintained in long-term culture (up to 72 hours) in order to exclude any interference as a consequence of therapy.

IL-8 response to TNF stimulation of T50M cells was similar to WT cells in agreement with findings from Churchman et al. [55], who found that the PBMCs carrying the T50M or C88R mutation, despite having elevated basal p65 nuclear expression, did not show further increase in p65 or p50 NF-κB subunits following stimulation with TNF. This relative low sensitivity of T50M mutant cells to TNF might be due to the low membranal expression of TNF-R1, as previously shown by flow cytometric FACS analysis [55] and confirmed in the present study by immunofluorescence (see Figure 1). However, our findings are in disagreement with those from Nedjai et al. [35], who studied the T50K mutation. This supports the notion that the molecular structure of the replacement amino acid (Methionine-M not Lysine-K), although involving the same tyrosine residue at position 79 in the mature protein, might differently affect receptor function.

In view of these considerations, we performed the same experiments using IL-1β stimulation. In a physiological state, IL-1β did not apparently influence NF-κB activity in the cell line considered. Instead, in the TNFRSF1A mutated cells, this cytokine induced an inflammatory response. The IL-1R pathway proceeded in canonical NF-κB pathway. We suggest that IL-1b enhances the inflammatory response of TNRSF1A mutated cells due to their hyper-inflammatory background.

Conclusions

We identified and functionally characterized a new (S59P) TNFRSF1A mutation. This mutation is associated with a TRAPS phenotype characterized by a high degree of inflammation only partially responsive to steroid treatment. This phenotype appeared to be highly responsive to anakinra, which was used in the patient in question over the course of one year. The S59P mutation determines a constitutive activation of the IL-1R pathway, inhibition of apoptosis, and an enhanced and persistent NF-κB activation and cytokines secretion in response to IL-1β stimulation.

Abbreviations

- CRDs:

-

Cysteine-rich domains

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- DD:

-

Death domains

- IL-1R:

-

Interleukin 1 receptor

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- PBMCs:

-

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffered saline

- SAA:

-

Serum amyloid A

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- TNF-R1:

-

Tumor-necrosis factor receptor 1

- TRAPS:

-

Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome

- WT:

-

Wild-type

References

McDermott MF, Aksentijevich I, Galon J, McDermott EM, Ogunkolade BW, Centola M, et al. Germline mutations in the extracellular domains of the 55 kDa TNF receptor, TNFR1, define a family of dominantly inherited autoinflammatory syndromes. Cell. 1999;97:133–44.

De Sanctis S, Nozzi M, Del Torto M, Scardapane A, Gaspari S, de Michele G, et al. Autoinflammatory syndromes: diagnosis and management. Italian J Pediatr. 2010;36:57.

Schmaltz R, Vogt T, Reichrath J. Skin manifestations in tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS). Dermatoendocrinol. 2010;2:26–9.

Rigante D, Cantarini L, Imazio M, Lucherini OM, Sacco E, Galeazzi M, et al. Autoinflammatory diseases and cardiovascular manifestations. Ann Med. 2011;43:341–6.

Lockslaey RM, Killeen N, Lenardo MJ. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: integrating mammalian biology. Cell. 2001;104:487–501.

Tuma R, Russell M, Rosendahl M, Thomas Jr GJ. Solution conformation of the extracellular domain of the human tumor necrosis factor receptor probed by Raman and UV-resonance Raman spectroscopy: structural effects of an engineered PEG linker. Biochem. 1995;34:15150–6.

Micheau O, Tschopp J. Induction of TNF receptor I-mediated apoptosis via two sequential signalling complexes. Cell. 2003;114:181–90.

Ea CK, Deng L, Xia ZP, Pineda G, Chen ZJ. Activation of IKK by TNFalpha requires site-specific ubiquitination of RIP1 and polyubiquitin binding by NEMO. Mol Cell. 2006;22:245–57.

Chen G, Goeddel DV. TNF-R1 signalling: a beautiful pathway. Science. 2002;296:1634–5.

May MJ, Ghosh S. Rel/NF-kappa B and I kappa B proteins: an overview. Semin Cancer Biol. 1997;8:63–73.

Bonizzi G, Karin M. The two NF-kB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptative immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004;26:280–8.

Schmitz ML, Mattioli I, Buss H, Kracht M. NF-κB: a multifaceted transcription factor regulated at several levels. Chembiochem. 2004;5:1348–58.

Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2195–224.

Moynagh PN. The NF-kappaB pathway. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4589–92.

Viatour P, Merville MP, Bours V, Chariot A. Phosphorylation of NF-κB and IκB proteins: implications in cancer and inflammation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:43–52.

Zhou Z, Connell MC, MacEwan DJ. TNFR1-induced NF-κB, but not ERK, p38MAPK or JNK activation, mediates TNF-induced ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression on endothelial cells. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1238–48.

Cabal-Hierro L, Lazo PS. Signal transduction by tumor necrosis factor receptors. Cell Signal. 2012;24:1297–305.

Milhavet F, Cuisset L, Hoffman HM, Slim R, El-Shanti H, Aksentijevich I, et al. The infevers autoinflammatory mutation online registry: update with new genes and functions. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:803–8.

Cantarini L, Lucherini OM, Muscari I, Frediani B, Galeazzi M, Brizi MG, et al. Tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS): state of the art and future perspectives. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:38–43.

Aksentijevich I, Galon J, Soares M, Mansfield E, Hull K, Oh HH, et al. The tumor-necrosi-factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome: new mutation in TNFRSF1A, ancestral origins, genotype-phenotype studies and evidence for further genetic heterogeneity of periodic fevers. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:301–14.

Hull KM, Drewe E, Aksentijevich I, Singh HK, Wong K, McDermott EM, et al. The TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS): emerging concepts of an autoinflammatory disorder. Medicine. 2002;81:349–68.

Pelagatti MA, Meini A, Caorsi R, Cattalini M, Federici S, Zulian F, et al. Long-term clinical profile of children with the low-penetrance R92Q mutation of the TNFRSF1A gene. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:1141–50.

Ravet N, Rouaghe S, Dodé C, Bienvenu J, Stirnemann J, Lévy P, et al. Clinical significance of P46L and R92Q substitutions in the tumour necrosis factor superfamily 1A gene. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:158–62.

Cantarini L, Lucherini OM, Cimaz R, Baldari CT, Bellisai F, Rossi Paccani S, et al. Idiopathic recurrent pericarditis refractory to colchicine treatment can reveal tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2009;22:1051–8.

Cantarini L, Lucherini OM, Cimaz R, Galeazzi M. Recurrent pericarditis caused by a rare mutation in the TNFRSF1A gene and with excellent response to anakinra treatment. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28:802.

Ganeff C, Remouchamps C, Boutaffala L, Benezech C, Galopin G, Vandepaer S, et al. Induction of the alternative NF-κB pathway by lymphotoxin αβ (LTαβ) relies on internalization of LTβ receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:4319–34.

Pavlov MY, Watts RE, Zhongping T, Cornish VW, Ehrenberg M, Forster AC. Slow peptide bond formation by proline and other N-alkyloamino acids in translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;106:50–4.

Galon J, Aksentijevich I, McDermott MF, O’Shea JJ, Kastner DL. TNFRSF1A mutations and autoinflammatory syndromes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:479–86.

Huggins ML, Radford PM, McIntosh RS, Bainbridge SE, Dickinson P, Draper-Morgan KA, et al. Shedding of mutant tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily 1A associated with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome: differences between cell types. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2651–9.

Yousaf N, Gould DJ, Aganna E, Hammond L, Mirakian RM, Turner MD, et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptor I from patients with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome interacts with wild-type tumor necrosis factor receptor I and induces ligand-independent NF-κB activation. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;52:2906–16.

Lobito AA, Kimberley FC, Muppidi JR, Komarow H, Jackson AJ, Hull KM, et al. Abnormal disulfide-linked oligomerization results in ER retention and altered signaling by TNFR1 mutants in TNFR1-associated periodic fever syndrome (TRAPS). Blood. 2006;108:1320–7.

Rebelo SL, Bainbridge SE, Amel-Kashipaz MR, Radford PM, Powell RJ, Todd I, et al. Modeling of tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily 1A mutants associated with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome indicates misfolding consistent with abnormal function. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2674–87.

Simon A, Park H, Maddipati R, Lobito AA, Bulua AC, Jackson AJ, et al. Concerted action of wild-type and mutant TNF receptors enhances inflammation in TNF receptor 1-associated periodic fever syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9801–6.

Nedjai B, Hitman GA, Yousaf N, Chernajovsky Y, Stjernberg-Salmela S, Pettersson T, et al. Abnormal tumor necrosis factor receptor I cell surface expression and NF-kappaB activation in tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:273–83.

Nedjai B, Hitman GA, Church LD, Minden K, Whiteford ML, McKee S, et al. Differential cytokine secretion results from p65 and c-Rel NF-κB subunit signalling in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome patients. Cell Immunol. 2011;268:55–9.

Bulua AC, Simon A, Maddipati R, Pelletier M, Park H, Kim KY, et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species promote production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and are elevated in TNFR1-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS). J Exp Med. 2011;208:519–33.

Dickie LJ, Aziz AM, Savic S, Lucherini OM, Cantarini L, Geiler J, et al. Involvement of X-box binding protein 1 and reactive oxygen species pathways in the pathogenesis of tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:2035–43.

D’Osualdo A, Ferlito F, Prigione I, Obici L, Meini A, Zulian F, et al. Neutrophils from patients with TNFRSF1A mutations display resistance to tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis: pathogenetic and clinical implication. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:998–1008.

Negm OH, Mannsperger HA, McDermott EM, Drewe E, Powell RJ, Todd I, et al. A pro-inflammatory signalome is constitutively activated by C33Y mutant TNF receptor 1 in TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS). Eur J Immunol. 2014;44:2096–110.

Mannsperger HA, Gade S, Henjes F, Beissbarth T, Korf U. RPP analyzer: analysis of reverse-phase protein array data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2202–3.

Cawthorn WP, Sethi JK. TNF-alpha and adipocyte biology. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:117–31.

Aganna E, Hammond L, Hawkins PN, Aldea A, McKee SA, van Amstel HK, et al. Heterogeneity among patients with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome phenotypes. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2632–44.

Lachmann HJ, Papa R, Gerhold K, Obici L, Touitou I, Cantarini L, et al. The phenotype of TNF receptor-associated autoinflammatory syndrome (TRAPS) at presentation: a series of 158 cases from the Eurofever/EUROTRAPS international registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:2160–7.

Lewis AK, Valley CC, Sachs JN. TNFR1 signalling is associated with backbone conformational changes of receptor dimmers consistent with overactivation in the R92Q TRAPS mutant. Biochemistry. 2012;51:6545–55.

Todd I, Radford PM, Draper-Morgan KA, McIntosh R, Bainbridge S, Dickinson P, et al. Mutant forms of tumour necrosis factor receptor I that occur in TNF-receptor-associated periodic syndrome retain signalling functions but show abnormal behaviour. Immunology. 2004;113:65–79.

Drewe E, Powell RJ. Clinically useful monoclonal antibodies in treatment. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:81–5.

Jacobelli S, André M, Alexandra JF, Dodé C, Papo T. Failure of anti-TNF therapy in TNF Receptor 1-Associated Periodic Syndrome (TRAPS). Rheumatology. 2007;46:1211–2.

Gattorno M, Pelagatti MA, Meini A, Obici L, Barcellona R, Federici S, et al. Persistent efficacy of anakinra in patients with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1516–20.

Dinarello CA. Interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Blood. 2011;117:3720–32.

Dinarello CA, van der Meer JWM. Treating inflammation by blocking interleukin-1 in humans. Semin Immunol. 2013;25:469–84.

Bachetti T, Ceccherini I. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome as a model linking autophagy and inflammation in protein aggregation diseases. J Mol Med. 2014;92:583–94.

Saklatvala J, Davis W, Guesdon F. Interleukin 1 (IL1) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) signal transduction. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1996;351:151–7.

Wajant H, Pfizenmaier K, Scheurich P. Tumor necrosis factor signalling. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:45–65.

Alcamo E, Mizgerd JP, Horwitz BH, Bronson R, Beg AA, Scott M, et al. Targeted mutation of TNF receptor I rescues the RelA-deficient mouse and reveals a critical role for NF-kappa B in leukocyte recruitment. J Immunol. 2001;167:1592–600.

Churchman SM, Church LD, Savic S, Coulthard LR, Hayward B, Nedjai B, et al. A novel TNFRSF1A splice mutation associated with increased nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kappaB) transcription factor activation in patients with tumour necrosis factor receptor associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1589–95.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Lucy Fairclough (School of Life Sciences, The University of Nottingham, UK) for her technical support and constructive discussion. We acknowledge The Jones 1986 Charitable Trust for founding the experiments performed in Nottingham, UK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EG, MP, DB LP conceived the study, participated in its design, analysis, interpretation and coordination and drafted the manuscript. EG, AA, AG, FN, ED, MDB, AR, LO, SD and GM carried out sequencing, cell transfection, immunofluorescence, western blot and cytokine assays, data analysis and interpretation. PS, FC, and LP supplied the clinical samples, interpreted data and helped prepare the manuscript. PG, OHN, PT and IT carried out RPPA, data analysis and interpretation. All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

List of primary antibodies used in TNF-R1 signalling study. For lysate microarray (RPPA) analysis, they were diluted as shown in the table.

Additional file 2:

RPPA data obtained from unstimulated, TNF and IL-1β stimulated wild-type (WT) and mutant HEK-293 cells. For any target, data are reported as mean ± SE (two independent experiments) percentage changes in fluorescence intensity, with respect of WT-HEK293 unstimulated cells. The statistical analysis was made by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni’s test for pairwise comparisons. Unstimulated mutants were compared with each other (row ANOVA). Considering each cell line, the results obtained after TNF and IL-1β stimulation were compared with those from unstimulated cells (column ANOVA).

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Greco, E., Aita, A., Galozzi, P. et al. The novel S59P mutation in the TNFRSF1A gene identified in an adult onset TNF receptor associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS) constitutively activates NF-κB pathway. Arthritis Res Ther 17, 93 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-015-0604-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-015-0604-7