Abstract

In recent years, the treatment options for patients with severe cardiorespiratory failure have been extended by the implementation of mechanical circulatory support (MCS). Identification of patients that benefit most from this cost-intensive treatment modality is of central importance, but is also challenging. Previous studies unravelled certain patient characteristics that should be taken into account, such as age, weight, and underlying pathology, and also the delay until MCS implementation as well as tissue hypoxia as prognostic factors. Relevant comorbidities included neurologic, renal, and hepatic disorders. Of note, baseline liver function tests predicted outcome in patients on extracorporeal life support (ECLS), including short-term and long-term mortality. Most strikingly, increased levels of alkaline phosphatase and total bilirubin indicated unfavourable short-term and long-term survival even after adjustment for age, gender, left ventricular function, and relevant known comorbidities such as impaired renal function and diabetes. Therefore, the assessment of liver function tests may be regarded as another piece in the complex puzzle of our efforts perceiving the ideal ECLS candidate with positive long-term outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Over the last decade, the treatment of patients with severe cardiorespiratory failure has witnessed a dynamic evolution of new treatment options [1, 2]. This includes providing temporary support for cardiac or pulmonary function using mechanical circulatory support (MCS) devices, referred to as extracorporeal life support (ECLS). Available devices provide adequate oxygenation and cardiac output whilst bypassing the physiological circulation, and are usually implemented in the emergency department or on intensive care units. Treatment protocols for peripheral veno-arterial implementation in patients with cardiogenic shock or as escalation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation have changed the landscape of therapeutic options in this patient population [3, 4]. In addition, using ECLS provides a temporary option to bridge patients towards recovery or alternative therapies such as heart transplantation or durable assist devices. However, in the light of the increasing number of MCS implementations, identifying patients that benefit from these cost-intensive treatment modalities is of utmost importance to facilitate individual decision-making based on a thorough risk–benefit evaluation. Although cardiocirculatory failure is often the central underlying aetiology, the prognosis of these patients is often determined by (multi-)organ failure [5]. Therefore, the article by Roth et al., investigating whether liver function predicts outcome in patients on ECLS, addresses an important topic [1].

The central dilemma of the quick decision as to who should or should not receive ECLS therapy is the lack of data. No randomised trials exist, and thus available data are mainly derived from retrospective registries or anecdotal cases. Still, there is agreement that contraindications to ECLS present conditions associated with particularly poor outcome. These have been recently reviewed in this journal [6]. Poor ECLS candidates are patients with severe neurologic injuries, intracranial or major haemorrhage, immunosuppression, (irreversible) multi-organ failure, disseminated malignancy, or patients with advanced age or already impaired quality-of-life. In addition, ECLS is not possible in patients with aortic dissection or severe aortic regurgitation since this leads to further deterioration of the underlying pathology. Another consideration that needs to be taken into account is that treatment modalities have to be available after successful stabilization with ECLS, such as heart transplantation or ventricular assist device therapy in case of persisting heart failure.

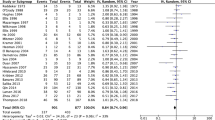

Besides some smaller registries indicating that the duration [7] and extent of tissue hypoxia as determined by increased lactate levels [4, 5] have prognostic implications, the most advanced database has been published by Schmidt et al. leading to the construction of the “survival after veno-arterial-ECMO” (SAVE) score [8]. Along with selected patient characteristics, such as age, weight, underlying pathology, and also delay of MCS implementation and tissue hypoxia, the likelihood of survival can be calculated. Relevant comorbidities include neurologic, renal, and hepatic disorders.

In their article, Roth et al. confirm that, in patients undergoing veno-arterial ECLS therapy following cardiovascular surgery, liver function tests are strong predictors of short-term and long-term mortality. The majority of the patients suffered from circulatory failure or cardiogenic shock defined as hypotension despite optimal fluid and catecholamine therapy and signs of anaerobic metabolism. Although this cohort of postoperative patients differs from patients that receive ECLS support in more urgent situations, the study indicates the usefulness of evaluating liver function before ECLS initiation. Increased levels of alkaline phosphatase and total bilirubin indicated increased short-term and long-term mortality even after adjustment for age, gender, left ventricular function, and relevant known comorbidities such as impaired renal function and diabetes. The authors conclude that these values could possibly help guide therapy decisions.

These data are in line with recent findings stressing the importance of liver function and dysfunction in cardiovascular patients. This applies for different patient cohorts. Murata et al. provided convincing evidence that the assessment of liver dysfunction using the model of end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores can be used for predicting postoperative morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing cardiac surgery [9]. In parallel, the assessment of liver function also provides prognostic information in patients with heart failure [10] or patients receiving heart transplantation [11]. Other laboratory values are also of interest for evaluating liver function in cardiovascular diseases. Increased international normalized ratio (INR) has been proven to be an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in acutely decompensated heart failure patients without anticoagulation, summarizing coagulation abnormalities and hepatic insufficiency [12]. Okada and co-workers speculated that their finding in heart failure patients could be related to systemic inflammation, neurohormonal activation, or venous congestion which might also differ within this patient population [12].

Another publication sheds additional light on the prognostic role of the liver in patients treated with ECLS. Mazzeffi et al. were able to show that 8 % of ECLS patients develop acute liver failure during ECLS, while patients with chronic liver disease or acute liver failure prior to ECLS initiation were excluded. In this study, the median ECLS duration for developing acute liver failure was 5 days and these patients has distinctly elevated mortality rates [13].

These recent findings stress the clinical relevance of inter-organ crosstalk mainly either on the basis of haemodynamic interplay or due to humoral soluble factors. Furthermore, these results deem the treating physician to take hepato-cardiac comorbidities into account during risk stratification and therapy planning. The findings of Roth et al. may be regarded as another piece in the complex puzzle of our efforts perceiving the ideal ECLS candidate with favourable long-term outcome.

Abbreviations

- ECLS:

-

extracorporeal life support

- MCS:

-

mechanical circulatory support

References

Roth C, Schrutka L, Binder C, Kriechbaumer L, Heinz G, Lang IM, et al. Liver function predicts survival in patients undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation following cardiovascular surgery. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):57.

Jung C, Ferrari M, Gradinger R, Fritzenwanger M, Pfeifer R, Schlosser M, et al. Evaluation of the microcirculation during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2008;40(4):311–4.

Rogers JG, O'Connor CM. The changing landscape of advanced heart failure therapeutics. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(14):1416–7.

Jung C, Janssen K, Kaluza M, Fuernau G, Poerner TC, Fritzenwanger M, et al. Outcome predictors in cardiopulmonary resuscitation facilitated by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Clin Res Cardiol. 2016;105(3):196–205.

Jung C, Figulla HR, Ferrari M. High frequency of organ failures during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: is the microcirculation the answer? Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89(1):345–6. author reply 346.

Mosier JM, Kelsey M, Raz Y, Gunnerson KJ, Meyer R, Hypes CD, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for critically ill adults in the emergency department: history, current applications, and future directions. Crit Care. 2015;19:431.

Shin TG, Choi JH, Jo IJ, Sim MS, Song HG, Jeong YK, et al. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation in patients with inhospital cardiac arrest: a comparison with conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(1):1–7.

Schmidt M, Burrell A, Roberts L, Bailey M, Sheldrake J, Rycus PT, et al. Predicting survival after ECMO for refractory cardiogenic shock: the survival after veno-arterial-ECMO (SAVE)-score. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(33):2246–56.

Murata M, Kato TS, Kuwaki K, Yamamoto T, Dohi S, Amano A. Preoperative hepatic dysfunction could predict postoperative mortality and morbidity in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: utilization of the MELD scoring system. Int J Cardiol. 2016;203:682–9.

Kim MS, Kato TS, Farr M, Wu C, Givens RC, Collado E, et al. Hepatic dysfunction in ambulatory patients with heart failure: application of the MELD scoring system for outcome prediction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(22):2253–61.

Grimm JC, Shah AS, Magruder JT, Kilic A. Valero 3rd V, Dungan SP, et al. MELD-XI score predicts early mortality in patients after heart transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100(5):1737–43.

Okada A, Sugano Y, Nagai T, Takashio S, Honda S, Asaumi Y, et al. Prognostic value of prothrombin time international normalized ratio in acute decompensated heart failure—a combined marker of hepatic insufficiency and hemostatic abnormality. Circ J. 2016.

Mazzeffi M, Kon Z, Sanchez P, Herr D. Impact of acute liver failure on mortality during adult ECLS. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(2):299–300.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CJ, MK, and RW drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

See related research by Roth et al., https://ccforum.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13054-016-1242-4

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Jung, C., Kelm, M. & Westenfeld, R. Liver function during mechanical circulatory support: from witness to prognostic determinant. Crit Care 20, 134 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1312-7

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1312-7