Abstract

Background

One of the central issues in microbial ecology is to understand the parameters that drive diversity. Among these parameters, size has often been considered to be the main driver in many different ecosystems. Surprisingly, the influence of size on gut microbial diversity has not yet been investigated, and so far in studies reported in the literature only the influences of age, diet, phylogeny and digestive tract structures have been considered. This study explicitly challenges the underexplored relationship connecting gut volume and bacterial diversity.

Results

The bacterial diversity of 189 faeces produced by 71 vertebrate species covering a body mass range of 5.6 log. The animals comprised mammals, birds and reptiles. The diversity was evaluated based on the Simpson Diversity Index extracted from 16S rDNA gene fingerprinting patterns. Diversity presented an increase along with animal body mass following a power law with a slope z of 0.338 ± 0.027, whatever the age, phylogeny, diet or digestive tract structure.

Conclusions

The results presented here suggest that gut volume cannot be neglected as a major driver of gut microbial diversity. The characteristics of the gut microbiota follow general principles of biogeography that arise in many ecological systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Among a number of parameters, the ‘size’ of an ecosystem is often assumed to have a key impact on the management of diversity. In fact, the species-area relationship is central to the ecological theory [1] and was first described for macro-organisms [2]. For bacteria, the species-area relationship is generally expressed in terms of habitat volume (i.e., volume-area relationship) and has been illustrated in liquid sump tanks of metal-cutting machines [3], membrane bioreactors [4] and tree holes (i.e., rainwater accumulated in holes at the base of large trees) [5]. However, until present, the microbial species-volume relationship has never yet been studied for gut or body size, even though vertebrate gut size covers a wide range of magnitudes. There is a 106 body mass factor between a tiny bird or a shrew and an elephant.

The vertebrate gut hosts a microbial community that fulfils many vital functions for the host: it enhances resistance to infection, stimulates mucosal immune defences, synthesizes essential vitamins and promotes caloric uptake by hydrolysing complex carbohydrates. The bacterial populations inhabiting the gut are complex, varying considerably from individual to individual and from species to species. However, gut microbial ecosystems are not a random association of microbes but are shaped by the host. A transfer occurs vertically from mothers to offspring or horizontally between individuals within a specific group. Such transfers have given rise to the long-standing co-evolution of microbiota and their hosts [6].

The benefit of bacterial diversity in the human gut has often been highlighted [7] and driving factors such as age [8], diverse lifestyles [9] and diet variations [10] have already been explored. Despite such an interest, the relationship between body mass and gut microbiota has never been explored whereas, in contrast, the positive links between the abundance of parasitic organisms or protozoal faunas and animal body size have been thoroughly referenced [11] [12]. The aim of the present study is to analyse a large bacterial dataset, comprising faeces collected from 71 different vertebrate species, in order to examine the effect of the volume-microbial diversity relationship in animal digestive tracts.

Methods

Sampling

All the animal samples were obtained from domesticated or captive populations in France (zoo, farm, aquarium, recreative farm or individual keeper). There is non-experimental research dedicated for this study, faeces samples were collected on ground with the animal keeper or animal owner without stresses for the animals. We obtained permissions from Lunaret zoo, Montpellier; Océanopolis, Brest; Réserve Africaine, Sigean; Mini Ferme Zoo, Cessenon sur Orb and consent from the animal owners (Jean-Philippe Steyer, Anais Bonnafous, Jean-Jacques Godon). Animal were living alone or in small groups (1 to 5). Furthermore, their food (meat, seeds, fruits or hay) were more standardized in comparison to wild diets.

Human stool specimens used in the present study were from infant and adult subjects included in international multicentric studies. Samples were collected between 2001 to 2005 and used on previous published studies. Infants samples were collected in the frame of the European project INFABIO (http://www.gla.ac.uk/departments/infabio/), ethical permission was obtained from Yorkhill Research Ethics Committee P16/03 and parents gave written informed consent [13]. Adults samples were collected in the frame of the European project Crownalife, the studies were approved by the Ethics Committee of Versailles Hospital Centre and written informed consent was obtained from all participants [14]. Approval for Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique to manage human-derived biological samples in accordance with Articles L.1243-3, R.1243-49 of “Code de la Santé Publique” was granted by the Ministry of Research and Education under number DC-2012-1728.

Faeces from 189 individuals belonging to 71 vertebrate species (31 mammals, 37 birds and 3 reptiles) were collected (Table 1). They were sub-divided into 80 categories according to species or to body mass (i.e., age (young–adult), sex (female–male), breed size (small–big–domesticated–wild), see Table 1). Body masses were provided by the breeder for large animals or obtained from literature for small animals. Body masses, along with diversity, were displayed with a logarithmic scale in order to highlight the linear shape of the power-law relationship. Except for the distinct dimorphism of male and female turkey samples, an average value of male and female body mass values was used. Dwarf or young individuals from the same species were also classified in specific body mass categories. For example, human samples were divided into two body mass categories: babies between 1 and 10 months old (mean of 5.8 kg) and adults between 29 and 61 years old (set at 70 kg). Composite faeces samples were avoided except for those that could not provide enough material for DNA extraction (less than 0.5 g).

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and Capillary Electrophoresis Single Strand Conformation Polymorphism (CE-SSCP) fingerprinting

Genomic DNAs were extracted from 0.5 g of raw material using the procedure described by Godon et al. [15]. The V3 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified with Bacteria-specific primers and PCR products were analysed by CE-SSCP analysis using an ABI3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) in accordance with a previously described method [16]. All raw CE-SSCP data are available on Additional file 4.

Calculation of diversity and statistical computing

Diversity was estimated by the Simpson Diversity Index from CE-SSCP fingerprinting patterns. The Simpson Diversity Index was expressed as \(D = {1 \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 {\sum {_{i = 1}^{p} a_{i}^{2} } }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\sum {_{i = 1}^{p} a_{i}^{2} } }}\) where \(a_{i}\) is the relative abundance of each CE-SSCP peak p. This index was directly calculated from each CE-SSCP fingerprint [17] using the R StatFingerprints library [18].

Preference was given to the Simpson Diversity Index from CE-SSCP fingerprinting rather than the Richness estimation because: (1) neither fingerprinting nor sequencing data can provide a robust estimation of richness [19]; (2) the Simpson Diversity Index can be estimated accurately with CE-SSCP fingerprinting [17, 20].

A generalized linear model was applied to fit the relationship between body mass and diversity. ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc tests were used for determining the statistical difference between (sub-) categories and body mass or diversity, both expressed in a logarithmic scale. All statistics were performed under R software (version 3.1.2) [21]. The calculation of the slope z was based on the exponent of the power-law relationship as follows: diversity = c weightz.

Results and discussion

The bacterial diversity of faeces from 189 vertebrates belonging to 71 species (31 mammals, 37 birds and 3 reptiles) was analysed (Table 1; Fig. 1). Analysis was only focused on diversity (Simpson Diversity Index), which can be accurately measured according to CE-SSCP fingerprinting patterns [15] (see the “Methods” section and Additional file 1). Apart from their phylogenetic position, animals can also be classified according to: (1) their diet (herbivorous, granivorous, omnivorous, carnivorous, piscivorous and frugivorous); (2) their metabolic body mass (from 12 g (zebra finch) to 3500 kg (Asian elephant)); (3) the structure of their digestive tracts; (4) and the size of the animal husbandry group (small and large). The present study focused on bacterial diversity, although changes within the structure of the bacterial communities were not taken into account. This study is also based on two assumptions: (1) the gut size should be proportional to the animal body mass, as has been demonstrated for herbivores [22] and birds [23]; and (2) the microbial diversity of faeces should be similar to that in the gut [24].

Relationship between the animal body mass and the Simpson Diversity Index for gut microbiota. Diamonds, circles and triangles correspond to birds, mammals and reptiles, respectively. Small, medium and large sizes correspond to 1, 2–5, >10 individuals, respectively. Green, brown, grey, red, blue and yellow colors correspond to herbivorous, granivorous, omnivorous, carnivorous, piscivorous and frugivorous diets, respectively. Bold fonts make reference to the animals mentioned in the text

Results point to a correlation between animal body mass and microbial diversity (linear regression with a slope z of 0.338 ± 0.027; p value <2.2 × 10−16), irrespective of the diet, phylogeny or structure of the digestive tracts (Fig. 1). Consequently, the use of a greater amount of samples over a wider size range confirms previous works on unrelated bacterial communities that have suggested the existence of a link between volume and diversity in tree holes [5], membrane bioreactors [4] and metal-cutting fluid sump tanks [3]. In the present results, the Simpson Diversity Index ranges between 3.3 and 1789.5, thus corresponding to a 5.6 log body mass range (Fig. 1).

A wide variability in the diversity between individuals for a given species was observed. However the average diversity value for species that were represented by several individuals was close to the regression line (Fig. 1). For example, the average diversity value for adult human microbiota (34 samples) was 80.8 with a standard deviation of 294.2, and 23.7 ± 20.3 for the 15 baby human microbiota. As a matter of comparison, Trosvik et al. [25] observed a similar range of diversity (over 2 log-units of Shannon index) when analysing a time-series of 332 sequencings over 443 days, on a single male adult individual.

Animal gut microbiota covered a broad range of diversity ranging from 2.2 to 1808.0. This was comparable to the values found in various types of environment, like drinking water, raw milk, plant roots, activated sludge in wastewater treatment plants, compost or soil (Additional file 2). On one hand, the lowest diversity in gut microbiota varied around 2, similarly to those found in drinking water. On the other hand, the highest diversity in gut microbiota reaching about 1808 resembled the values found in soils (Additional file 2).

This vast range of variations in gut diversity is often associated with factors that are different to the body mass: diet [10], phylogeny [26], digestive tract structure [27], age [8] [28], way of life [29], ethnic origin [30], state of health (immune system, pregnancy, obesity) [31] [32], or genetic background [32]. Among these parameters, age has been well documented as the major one to explain these variations and the diversity or richness between human baby microbiota and those of adults [33] [34]. However the size of the gut also varies during infant growth. In this case, a difference in the microbial diversity between infant (29.9 ± 20.3) and adults (106.6 ± 76.0) was observed, concomitantly with changes in body mass when comparing human babies (6.5 ± 1.9) and adults (70 kg). The same observation was made for young and adult dog samples (Table 1). Furthermore, when comparing two penguin species that only differ in their body mass (only adult specimens, with the same diet and living in the same location), the relationship between microbial diversity and body mass still remain valid.

The correlation between body mass and diversity has been assessed for homogenous sub-categories (Table 2 and Additional file 3), thus excluding the potential effects of the different parameters. Indeed, the 189 samples could also be analysed according to phylogeny (reptile, bird, and mammal), diet (carnivorous, herbivorous, granivorous, omnivorous and piscivorous), gut structure (hindgut caecum, hindgut colon and foregut ruminant), age (baby and adult), and size of the animal husbandry group (small and large). Except for the latter category, all of them depended on the body mass (e.g. body mass was related to phylogeny, related to age or to ruminants). Significantly positive body mass/diversity correlations were observed for each sub-category, provided that a sufficient amount of data was available (over 50 samples minimum per sub-category) (Table 2; Additional file 3). The significant slopes z of the mass-diversity relationships generally ranged from 0.202 ± 0.043 to 0.380 ± 0.039. As the herbivorous group only contained 44 samples, the interestingly weak body mass diversity correlation with a z value of 0.137 could not be correctly interpreted.

The observed slope z was similar to that reported for ‘island’ patterns of bacterial diversity such as metal-cutting fluid sump tanks (z = 0.245–0.295) [3] and tree holes (z = 0.26) [5] and varied within a similar range to that reported for plants and animals from discrete islands (z = 0.25–0.35). The slope z-values reported for continuous patterns (such as marsh sediment [35] with z-values between 0.02 and 0.04) are generally much lower than those reported for discrete habitats.

According to these results, which confirm the assumption that species and volume are related, guts can compared to an archipelago, where microbes originating from feed tend to colonise the available niches provided by the gut. This is also in line with the MacArthur and Wilson biogeography theory [1]. Size, similarly to island environments appears to reflect the heterogeneity of the environment. Hence, a large gut size should provide more space, enabling a large microbial diversity to settle in [36].

Conclusions

The aim of this study was not to explain the genesis of bacterial diversity in vertebrate guts but was rather focused on producing evidence on the role of gut size in the maintenance of a level of microbial diversity. This work highlights the hitherto unexplored relationship between volume and diversity in the case of gut microbiota. Gut volume should henceforth be taken into account along with other parameters to explain the level of diversity. Finally, this work confirms the relevance of the microbial world when addressing ecological issues such as the relationship between species diversity and the size of the habitat [37].

Availability of supporting data

Our data are provided in the electronic supplementary materials (Additional file 4).

Abbreviations

- CE-SSCP:

-

capillary electrophoresis single strand conformation polymorphism

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- 16S rRNA:

-

16S ribosomal RNA

- ANOVA:

-

analysis of variance

References

MacArthur RH, Wilson EO. The theory of island biogeography. Princet Univ Press Monogr Popul Biol. 1967;1:202.

Arrhenius O. Species and area. J Ecol. 1921;9:95–9.

van der Gast CJ, Lilley AK, Ager D, Thompson IP. Island size and bacterial diversity in an archipelago of engineering machines. Environ Microbiol. 2005;7:1220–6.

Van der Gast CJ, Jefferson B, Reid E, Robinson T, Bailey MJ, Judd SJ, Thompson IP. Bacterial diversity is determined by volume in membrane bioreactors. Environ Microbiol. 2006;8:1048–55.

Bell T, Ager D, Song JI, Newman JA, Thompson IP, Lilley AK, van der Gast CJ. Larger islands house more bacterial taxa. Science. 2005;308:1884.

Ley RE, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Ecological and evolutionary forces shaping microbial diversity in the human intestine. Cell. 2006;124:837–48.

Le Chatelier E, Nielsen T, Qin J, Prifti E, Hildebrand F, Falony G, Almeida M, Arumugam M, Batto J-M, Kennedy S, Leonard P, Li J, Burgdorf K, Grarup N, Jorgensen T, Brandslund I, Nielsen HB, Juncker AS, Bertalan M, Levenez F, Pons N, Rasmussen S, Sunagawa S, Tap J, Tims S, Zoetendal EG, Brunak S, Clement K, Dore J, Kleerebezem M, et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature. 2013;500:541.

Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Baldassano RN, Anokhin AP, Heath AC, Warner B, Reeder J, Kuczynski J, Caporaso JG, Lozupone CA, Lauber C, Clemente JC, Knights D, Knight R, Gordon JI. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486:222.

Schnorr SL, Candela M, Rampelli S, Centanni M, Consolandi C, Basaglia G, Turroni S, Biagi E, Peano C, Severgnini M, Fiori J, Gotti R, De Bellis G, Luiselli D, Brigidi P, Mabulla A, Marlowe F, Henry AG, Crittenden AN. Gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3654.

Vital M, Gao J, Rizzo M, Harrison T, Tiedje JM. Diet is a major factor governing the fecal butyrate-producing community structure across mammalia aves and reptilia. ISME J. 2015;9:832–43.

Kamiya T, O’Dwyer K, Nakagawa S, Poulin R. What determines species richness of parasitic organisms? A meta-analysis across animal, plant and fungal hosts. Biol Rev. 2014;89:123–34.

Clauss M, Mueller K, Fickel J, Streich WJ, Hatt J-M, Suedekum K-H. Macroecology of the host determines microecology of endobionts: protozoal faunas vary with wild ruminant feeding type and body mass. J Zool. 2011;283:169–85.

Fallani M, Amarri S, Uusijarvi A, Adam R, Khanna S, Aguilera M, Gil A, Vieites JM, Norin E, Young D, Scott JA, Doré J, Edwards CA, Team I. Determinants of the human infant intestinal microbiota after the introduction of first complementary foods in infant samples from five European centres. Microbiol SGM. 2011;157:1385–92.

Mueller S, Saunier K, Hanisch C, Norin E, Alm L, Midtvedt T, Cresci A, Silvi S, Orpianesi C, Verdenelli MC, Clavel T, Koebnick C, Zunft HJF, Dore J, Blaut M. Differences in fecal microbiota in different European study populations in relation to age, gender, and country: a cross-sectional study. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:1027–33.

Godon JJ, Zumstein E, Dabert P, Habouzit F, Moletta R. Molecular microbial diversity of an anaerobic digestor as determined by small-subunit rDNA sequence analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2802–13.

Wéry N, Bru-Adan V, Minervini C, Delgénes JP, Garrelly L, Godon JJ. Dynamics of Legionella spp. and bacterial populations during the proliferation of L. pneumophila in a cooling tower facility. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:3030–7.

Haegeman B, Sen B, Godon JJ, Hamelin J. Only simpson diversity can be estimated accurately from microbial community fingerprints. Microb Ecol. 2014;68:169–72.

Michelland RJ, Dejean S, Combes S, Fortun-Lamothe L, Cauquil L. StatFingerprints: a friendly graphical interface program for processing and analysis of microbial fingerprint profiles. Mol Ecol Resour. 2009;9:1359–63.

Haegeman B, Hamelin J, Moriarty J, Neal P, Dushoff J, Weitz JS. Robust estimation of microbial diversity in theory and in practice. ISME J. 2013;7:1092–101.

Lalande J, Villemur R, Deschenes L. A new framework to accurately quantify soil bacterial community diversity from DGGE. Microb Ecol. 2013;66:647–58.

R-Core-Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014.

Clauss M, Schwarm A, Ortmann S, Streich WJ, Hummel J. A case of non-scaling in mammalian physiology? Body size, digestive capacity, food intake, and ingesta passage in mammalian herbivores. Comp Biochem Physiol A: Mol Integr Physiol. 2007;148:249–65.

Lavin SR, Karasov WH, Ives AR, Middleton KM, Garland T Jr. Morphometrics of the avian small intestine compared with that of nonflying mammals: a phylogenetic approach. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2008;81:526–50.

Michelland RJ, Monteils V, Zened A, Combes S, Cauquil L, Gidenne T, Hamelin J, Fortun-Lamothe L. Spatial and temporal variations of the bacterial community in the bovine digestive tract. J Appl Microbiol. 2009;107:1642–50.

Trosvik P, de Muinck EJ, Stenseth NC. Biotic interactions and temporal dynamics of the human gastrointestinal microbiota. ISME J. 2015;9:533–41.

Ley RE, Lozupone CA, Hamady M, Knight R, Gordon JI. Worlds within worlds: evolution of the vertebrate gut microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:776–88.

Stevens CE, Hume ID. Comparative physiology of the vertebrate digestive system. Cambridge: University Press; 2004.

Waite DW, Eason DK, Taylor MW. Influence of hand rearing and bird age on the fecal microbiota of the critically endangered kakapo. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:4650–8.

Dicksved J, Floistrup H, Bergstrom A, Rosenquist M, Pershagen G, Scheynius A, Roos S, Alm JS, Engstrand L, Braun-Fahrlander C, von Mutius E, Jansson JK. Molecular fingerprinting of the fecal microbiota of children raised according to different lifestyles. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:2284–9.

Kwok L, Zhang J, Guo Z, Gesudu Q, Zheng Y, Qiao J, Huo D, Zhang H. Characterization of fecal microbiota across seven chinese ethnic groups by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):93631.

Rescigno M. Intestinal microbiota and its effects on the immune system. Cell Microbiol. 2014;16:1004–13.

Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, Sogin ML, Jones WJ, Roe BA, Affourtit JP, Egholm M, Henrissat B, Heath AC, Knight R, Gordon JI. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–7.

Koenig JE, Spor A, Scalfone N, Fricker AD, Stombaugh J, Knight R, Angenent LT, Ley RE. Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:4578–85.

Henderson G, Cox F, Ganesh S, Jonker A, Young W, Collaborators GRC, Janssen PH. Rumen microbial community composition varies with diet and host, but a core microbiome is found across a wide geographical range. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14567.

Horner-Devine MC, Lage M, Hughes JB, Bohannan BJM. A taxa–area relationship for bacteria. Nature. 2004;432:750–3.

Kassen R. The experimental evolution of specialists, generalists, and the maintenance of diversity. J Evol Biol. 2002;15:173–90.

Jessup CM, Kassen R, Forde SE, Kerr B, Buckling A, Rainey PB, Bohannan BJM. Big questions, small worlds: microbial model systems in ecology. Trends Ecol Evol. 2004;19:189–97.

Authors’ contributions

JJG designed the experiment, JJG and JH collected the data, PA performed the experiments and contributed to the analysis of the data. Analysis and interpretation were carried out by JH and JJG. JH and JJG contributed to the first draft, which was completed by JPS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following people and organizations who generously provided samples: Joël Doré; Thierry Gidenne; ‘Reserve africaine’, Sigean, France; ‘Mini-ferme zoo’, Cessenon/Orb, France; ‘Oceanopolis’, Brest, France; and Lunaret Zoo, Montpellier, France. We thank Biswarup Sen, Anais Bonnafous and Valérie Bru-Adan for technical assistance. INRA funded this research.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

12898_2016_71_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Additional file 2. Simpson Diversity Index calculated from 671 CE-SSCP fingerprinting patterns. Samples were grouped according to their ecosystem of origin.

12898_2016_71_MOESM3_ESM.pdf

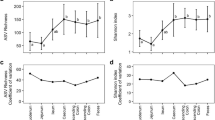

Additional file 3. Simpson Diversity Index as a function of animal weight for (A) all the samples and for the sub-categories; (B) diet; (C) phylogeny; (D) gut structure; (E) age and (F) group size. The slope of the linear regression is indicated.

12898_2016_71_MOESM4_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 4. Raw 671 CE-SSCP profiles. Columns correspond to the samples. The 7359 lines correspond to the fluorescence intensity according to time.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Godon, JJ., Arulazhagan, P., Steyer, JP. et al. Vertebrate bacterial gut diversity: size also matters. BMC Ecol 16, 12 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-016-0071-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-016-0071-2