Abstract

Introduction

The purpose of this observational study was to analyze the rates, characteristics and associated risk factors of severe infections in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases (SAD) who were treated off-label with biological agents in daily practice.

Methods

The BIOGEAS registry is an ongoing Spanish prospective cohort study investigating the long-term safety and efficacy of the off-label use of biological agents in adult patients with severe, refractory SAD. Severe infections were defined according to previous studies as those that required intravenous treatment or that led to hospitalization or death. Patients contributed person-years of follow-up for the period in which they were treated with biological agents.

Results

A total of 344 patients with SAD treated with biological agents off-label were included in the Registry until July 2010. The first biological therapies included rituximab in 264 (77%) patients, infliximab in 37 (11%), etanercept in 21 (6%), adalimumab in 19 (5%), and 'other' agents in 3 (1%). Forty-five severe infections occurred in 37 patients after a mean follow-up of 26.76 months. These infections resulted in four deaths. The crude rate of severe infections was 90.9 events/1000 person-years (112.5 for rituximab, 76.9 for infliximab, 66.9 for adalimumab and 30.5 for etanercept respectively). In patients treated with more than two courses of rituximab, the crude rate of severe infection was 226.4 events/1000 person-years. A pathogen was identified in 24 (53%) severe infections. The most common sites of severe infection were the lower respiratory tract (39%), bacteremia/sepsis (20%) and the urinary tract (16%). There were no significant differences relating to gender, SAD, agent, other previous therapies, number of previous immunosuppressive agents received or other therapies administered concomitantly. Cox regression analysis showed that age (P = 0.015) was independently associated with an increased risk of severe infection. Survival curves showed a lower survival rate in patients with severe infections (log-rank and Breslow tests < 0.001).

Conclusions

The rates of severe infections in SAD patients with severe, refractory disease treated depended on the biological agent used, with the highest rates being observed for rituximab and the lowest for etanercept. The rate of infection was especially high in patients receiving three or more courses of rituximab. In patients with severe infections, survival was significantly reduced. Older age was the only significant predictive factor of severe infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent decades, the standard of care for patients with systemic autoimmune diseases (SAD) has been based on corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents, although scientific evidence of their efficacy and safety relies principally on data from uncontrolled studies. The complexity of therapy in patients with SAD is increased by the large number of patients who do not respond to first-line therapies and those who relapse after initial clinical remission. In these patients, there is even less scientific evidence available for the use of second-line drugs, which are often prescribed according to individual clinical decisions. The emergence of biological therapies has increased the therapeutic armamentarium available in these complex situations. These therapies are used for a rapidly increasing number of cases of SAD [1] even though they are not yet licensed for this use by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMEA). This off-label use is mainly employed to treat patients with either life-threatening situations, or severe involvement refractory or intolerant to standard therapy.

The risk of severe infection is a key factor in assessing the risks and benefits of using biologic agents to treat patients with SAD, especially as the use is off-label. Available data on the safety of biologic agents in SAD come from some randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and, especially, from a large number of small observational studies and case reports [2]. In RCTs, the prevalence of severe infection is less than 10% [3–16], but it is unclear whether the safety data obtained in these trials can be extrapolated to clinical practice. In RCTs, patients with associated processes or comorbidities are often excluded, meaning that the patient population tested is clearly different from patients treated in real-life conditions, in which biologic therapy is often more prolonged and patients have usually received long prior courses of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents. There is little information on the rate of severe infections in large series of patients with SAD treated off-label with biologic agents in clinical practice [17, 18].

The purpose of this observational study was to analyze the rates, characteristics, and associated risk factors of severe infections in patients with SAD treated off-label with biologic agents in daily practice.

Materials and methods

Registry

The BIOGEAS (Spanish Study Group of Biological Agents in Autoimmune Diseases) registry is an ongoing Spanish prospective cohort study which since 2002 has been investigating the long-term safety and efficacy of the off-label use of biologic agents in adult patients with severe, refractory SAD [17]. By July 2010, the database included 344 patients reported by 21 Spanish departments of internal medicine. The SAD includes systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjögren syndrome, systemic sclerosis, polymyosistis, dermatomyositis, polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss vasculitis, microscopic polyangiitis, giant cell arteritis, cryoglobulinemia, Behçet disease, sarcoidosis, adult-onset Still disease, antiphospholipid syndrome, relapsing polychondritis, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, antisynthetase syndrome, and rheumatic polymyalgia. Diagnosis of SAD is based on the current international classification criteria for each disease. The inclusion criteria are: i) severe disease, defined as the development of potentially life-threatening clinical manifestations; or ii) refractory disease, defined as patients not achieving remission or relapsing, or patients with progressive disease despite optimal doses of corticosteroids and who have failed with at least two consecutive therapies considered as the standard of care for the corresponding autoimmune disease.

Data collection

Data were collected at baseline (time of first administration of the drug), at six months and then every 12 months or at disease relapse, using an electronic case report form. To minimize possible interobserver bias, the inclusion criteria and variables of the protocol were agreed by all participating centers. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the coordinating center (Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, Spain) and then by each participating center. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Baseline assessment

Baseline information was collected on all patients in the BIOGEAS registry at the initiation of biologic therapy and included demographic data, disease duration, previous therapies, biologic agent, dosage, number of infusions/subcutaneous administrations, concomitant drugs, therapeutic response, relapses, retreatments and switches, adverse events, and outcomes.

Definition of severe infection

Severe infections were defined according to previous studies [19, 20] as those that required intravenous treatment or that led to hospitalization or death. Infections were classified by anatomic site and by microorganism.

Statistical analysis

Patients contributed person-years of follow up for the period in which they were treated with biologic agents. Patients who later switched to other biologic agents, in which case infection was attributed to the last administered therapy, and patients who were re-treated, contributed separate events and person-years for each different drug or therapy cycle; person-years were calculated from the first day of administration of the biologic agent to the date of the last administered dose until July 2010, drug discontinuation, or death. In patients who discontinued biologic therapy, infection rates were calculated according to an exposure period-at-risk model used in recent studies in rheumatic diseases [19, 20]. This type of model is in line with the recent European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)recommendations on the reporting of safety data in biologic registers [21], in order to address the possible impact of an ongoing attributable risk beyond the drug discontinuation date [21]. This model consists of adding a lag window period which, in our study, was defined according to the biologic agent used. For rituximab, infections were included if they occurred during the 12 months after each infusion (initial treatment and/or each subsequent infusion) [18]. For the remaining agents, overwhelmingly anti-TNF agents, the exposure period was defined as the active treatment period plus a 90-day lag window [19].

Rates of serious infections are presented as events/1,000 person-years and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Categorical data were compared using the chi squared and Fisher's exact tests. Continuous variables were analyzed with the Student's t-test in large samples of similar variance, with results indicated as mean * standard error of the mean (SEM), and with the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U-test for small samples, with results indicated as median and interquartiles. A two-tailed value of P < 0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance. When independent variables appeared to have statistical significance in the univariate analysis, they were included in a multivariate Cox regression analysis using a backward stepwise method allowing adjustment for the variables that were statistically significant (P < 0.05) in the univariate analysis. The hazard ratios (HR) and their 95% CI obtained in the adjusted regression analysis were calculated. Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients with and without severe infections were compared using the log-rank and Breslow tests. The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS program (IBM SPSS Statistics 19.0).

Results

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. A total of 344 patients with SAD treated with biologic agents off-label were included in the registry until July 2010. There were 270 (78%) women and 74 (22%) men, with a mean age of 42.74 ± 0.83 (range 16 to 82) years. The main SAD were SLE in 140 (41%) cases, systemic vasculitis in 50 (14%), inflammatory myopathies in 38 (11%), Sjögren syndrome in 23 (7%), and Behçet disease in 31 (9%). Previous therapies included corticosteroids in 332 (97%) cases, cyclophosphamide in 172 (50%), methotrexate in 109 (32%), mycophenolate in 98 (28%), azathioprine in 97 (28%), and intravenous immunoglobulins in 89 (26%). Biologic therapies were administered due to life-threatening situations in 48 (14%) patients. The first biologic therapy included rituximab in 264 (77%) patients, infliximab in 37 (11%), etanercept in 21 (6%), adalimumab in 19 (5%), and other agents in 3 (1%). Concomitant therapies are summarized in Table 1. Sixty-one (18%) patients were treated with two courses of biologics, 14 (4%) with three courses and 8 (2%) with four courses. In 33 (10%) patients, the first biologic agent was switched to another agent.

Rates of severe infections

Forty-five severe infections, which required hospitalization and/or intravenous antibiotics and/or resulted in death, occurred in 37 patients after a mean follow up of 26.76 months (six patients had two or more severe infections). Infections occurred during the first six months after initiation of therapy (63%), between months 6 and 12 of therapy (13%), and after one year of initiation of therapy (24%). These infections resulted in four deaths. The crude rate of severe infections was 90.9 events/1,000 person-years (95% CI 66.31 to 121.64). The crude rates of serious infections according to treatment were 112.5 events/1,000 person-years for rituximab (95% CI 79.20 to 155.10), 76.9 events/1,000 person-years for infliximab (95% CI 20.96 to 196.95), 66.9 events/1,000 person-years for adalimumab (95% CI 8.10 to 241.55) and 30.5 events/1,000 person-years for etanercept (95% CI 3.69 to 110.02; Table 2). The crude rates of serious infections were 90.2 events/1,000 person-years for refractory patients (95% CI 25.80 to 365.30) and 94.8 events/1,000 person-years for patients presenting with life-threatening situations (95% CI 38.12 to 195.35).

The crude rates of serious infections according to SAD were 147.2 events/1,000 person-years for systemic vasculitis (95% CI 73.50 to 263.30), 115.9 events/1,000 person-years for inflammatory myopathies (95% CI 46.60 to 238.70), 94.0 events/1,000 person-years for Sjögren syndrome (95% CI 19.38 to 274.66), 62.7 events/1,000 person-years for SLE (95% CI 31.30 to 112.20), and 32.6 events/1,000 person-years for Behçet disease (95% CI 3.95 to 117.95). Table 2 also includes the crude rates for the six most frequent disease/biologic agent combinations reported.

Retreatment and switches

We analyzed the percentage and rates of severe infections in patients treated with more than one course of rituximab. The percentage of infection was 25 of 264 (9%) in the first course, 2 of 38 (5%) in the second course and 3 of 15 (20%) in the third and subsequent courses; the crude rates were 119.0, 36.6, and 226.4 events/1,000 person-years, respectively. Severe infections occurred in 2 of 33 (6%) patients in whom the biologic agent was switched.

Pathogens

A pathogen was identified in 24 (53%) severe infections. Bacterial infections included Streptococcus pneumoniae (n = 3), Escherichia coli (n = 3), Staphylococcus aureus (n = 3), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 2), Staphylococcus sp (n = 1), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (n = 1), Enterococcus faecalis (n = 1), Corynebacterium (n = 1), and Proteus mirabillis (n = 1). Viral infections included cytomegalovirus (n = 3), and herpes simplex virus (n = 1). Fungal infections included candidiasis (n = 2), aspergillosis (n = 1), and Pneumocystis jiroveci infection (n = 1). There were three bacterial intracellular infections: Mycobacterium tuberculosis (n = 2) and Listeria monocytogenes (n = 1). Multibacterial infection was reported in one patient.

Site of infection

The most common site of severe infection was the lower respiratory tract (39%), bacteriemia/sepsis (20%), the urinary tract (16%), the skin and soft tissues (9%), the gastrointestinal tract (5%), the central nervous system (5%), upper respiratory tract (5%), and the bones and joints (2%). Five (13%) patients presented separate infections in different sites.

Risk factors for severe infections

Univariate analysis showed that patients who developed severe infections were older (49.14 vs 41.97 years, P = 0.008), had received methylprednisolone pulses less frequently (11% vs 27%, P = 0.043) and were treated concomitantly with cyclosporine A/tacrolimus more frequently (13% vs 5%, P = 0.041) in comparison with patients without severe infections (Table 3). There were no significant differences according to gender, SAD, agent, other previous therapies, number of previous immunosuppressive agents received, and other therapies administered concomitantly (Table 3). Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that age (HR 1.026, 95% CI 1.005-1.047, P = 0.014) was significantly associated with an increased risk of severe infection.

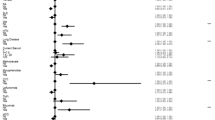

Mortality

Figure 1 shows the survival curves of patients according to the development or not of severe infections (log-rank and Breslow tests < 0.001).

Discussion

Biologic agents are currently used in patients with severe, refractory SAD even though they are not yet licensed for this use. Available scientific evidence comes from various RCTs but principally from a large number of observational studies and case reports. However, the results of uncontrolled studies and, especially, case reports may overstate the efficacy and understate the risks, due to the positive reporting and publication bias. One of the main concerns of the use of biologic agents is the potential risk of severe infections in patients with severe, refractory disease and a long-term history of the use corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents, which per se increases the risk of infection. The best evidence on the safety of biological agents in SAD come from RCTs. In a pooled analysis of RCTs published to date (Table 4) [3–16], the global percentage of adverse events was significantly higher in patients receiving biologic agents in comparison with those receiving placebo (59.4% vs 48.7%, P < 0.001, HR 1.54, 95% CI 1.20-1.97). However, there were no significant differences either in the percentage of total number of infections (30.7% vs 29.9%, P = 0.79) or the percentage of severe infections (8.3% vs 7.6%, P = 0.69). However, the prevalence and rates of severe infections in SAD patients treated with biologic agents off-label in clinical practice has not yet been determined. For this reason, the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine set up a national multicenter prospective registry intended to determine the tolerance to and efficacy of biologic agents in clinical practice. The results of the present study show that 11% of patients developed severe infections, with a crude rate of 91 severe infections/1,000 person-years.

The highest rate of severe infections was observed in SAD patients treated with rituximab, which was used in nearly 80% of our patients, the majority of whom had SLE, systemic vasculitis, or Sjogren syndrome. Since its introduction, rituximab has been increasingly used in patients with SAD and there are more than 1,000 reported cases [22], overwhelmingly from uncontrolled studies and case reports. However, the percentage and rates of severe infections are unclear. The results of five reported RCTs in SAD patients treated with rituximab [3–7] showed a percentage of severe infections of 10%, very similar to that found in patients receiving placebo (12%) (Table 4) and the results of this study (11%). Recent data from the French AIR Registry [18] showed a higher rate in 136 SLE patients treated with rituximab (66 severe infections per 1,000 person-years), similar to the rate found in our SLE patients (63 per 1,000 person-years). Our study is the first to analyze rates of severe infection in patients with a wide variety of SAD. We found the highest rates for vasculitis and inflammatory myopathies (147 and 116 per 1,000 person-years, respectively) and the lowest rate for Behçet disease (30 per 1,000 person-years). In addition, we found that the rates of severe infection differed according to the number of rituximab courses received, with a significantly increased risk in patients receiving three or more courses of rituximab.

The rate of severe infections in SAD patients treated with anti-TNF agents was 54 per 1,000 person-years, and was much higher for the monoclonal antibodies (infliximab and adalimumab) than for the soluble receptor (etanercept), in line with some recent studies suggesting a lower rate of infections in patients treated with etanercept [23, 24]. These rates are very similar to those reported in RCTs and postmarketing studies in patients with RA, which range between 17 and 64 per 1,000 person-years [25–30], although the differences between rheumatoid arthritis and the SAD studied here makes it difficult to compare infection rates. Infection of the lower respiratory or urinary tracts together with bacteremia/sepsis accounted for 75% of severe infections in our patients, with a microorganism being identified in more than 50% of episodes. Two patients treated with rituximab and no patients treated with anti-TNF agents developed tuberculosis. No patient developed progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

One of the objectives of this study was to identify possible baseline risk factors for the development of severe infections in SAD patients treated with biologic agents. In patients with RA, identified risk factors for severe infection include age, extraarticular involvement, leukopenia, low baseline IgG levels, corticosteroid dosage, and comorbidities [31–34]. The largest prospective study [34] identified older age, rheumatoid arthritis-related extraarticular involvement, chronic lung disease and/or heart failure, and IgG levels below 6 g/L as independent variables associated with severe infections. Although the differences between this study and our results are significant (design, disease evaluated, drug licensed, and variables analyzed), it is noteworthy that both studies identified age as an independent variable associated with an increased risk of infection. However, we found no association between previous or concomitant use of corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive agents (cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate, methotrexate, or azathioprine) and an increased risk of severe infection.

Possible concerns in observational studies include selection bias (in our study, only refractory/severe patients were included). This patient profile makes it impossible to compare our results with those of controlled studies, a bias that, in our opinion, is very difficult to avoid due to the lack of licensing for biologic agents in autoimmune diseases. In addition, the lack of a control group of SAD patients treated with non-biologic therapies did not permit the risk of infection to be compared. However, in contrast to rheumatoid arthritis, it is very difficult to design a case-control study in this setting (SAD patients with life-threatening situations or refractory to standard therapies). Our study has other limitations, including the lack of evaluation of some baseline factors that could influence the risk of infection, such as laboratory parameters (neutrophil/lymphocyte counts, serum IgG levels), corticosteroid dosage, and baseline disease activity. However, our population study (patients with refractory disease or life-threatening situations) defines per se a group of patients with a high baseline disease activity and, in fact, re-analysis showed no significant differences between the crude rate of infection in these two groups. Nevertheless, in spite of these limitations, we believe that the recruitment of nearly 350 patients with SAD treated off-label with biologic agents is significant and permits useful information on the characteristics and rates of severe infection associated with the off-label use of biologic agents in patients with severe, refractory disease to be obtained.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found a crude rate of severe infection of 91 events per 1,000 person-years in a large series of patients with SAD treated off-label with biologic therapies, with the highest rate being observed for rituximab and the lowest for etanercept. The only predictive factor independently associated with severe infection was age. Although awaiting the licensing of biologic agents for SAD, an assessment of the risk of serious adverse events versus the benefits of treatment should be made on an individual basis.

Abbreviations

- SAD:

-

systemic autoimmune diseases

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- EMEA:

-

European Medicines Agency

- RCT:

-

randomized controlled trial

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- SEM:

-

standard error of the mean

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- SLE:

-

systemic lupus erythematosus

- TNF:

-

tumor necrosis factor.

References

Silverman GJ, Weisman S: Rituximab therapy and autoimmune disorders: prospects for anti-B cell therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48: 1484-1492. 10.1002/art.10947.

Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, Muñoz S, Soto MJ, BIOGEAS STUDY Group: A systematic review of the off-label use of biological therapies in systemic autoimmune diseases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2008, 87: 345-364. 10.1097/MD.0b013e318190f170.

Meijer JM, Meiners PM, Vissink A, Spijkervet FK, Abdulahad W, Kamminga N, Brouwer E, Kallenberg CG, Bootsma H: Effectiveness of rituximab treatment in primary Sjögren's syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62: 960-968.

Dass S, Bowman SJ, Vital EM, Ikeda K, Pease CT, Hamburger J, Richards A, Rauz S, Emery P: Reduction of fatigue in Sjögren syndrome with rituximab: results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008, 67: 1541-1544.

Merrill JT, Neuwelt CM, Wallace DJ, Shanahan JC, Latinis KM, Oates JC, Utset TO, Gordon C, Isenberg DA, Hsieh HJ, Zhang D, Brunetta PG: Efficacy and safety of rituximab in moderately-to-severely active systemic lupus erythematosus: the randomized, double-blind, phase II/III systemic lupus erythematosus evaluation of rituximab trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62: 222-233. 10.1002/art.27233.

Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, Seo P, Langford CA, Hoffman GS, Kallenberg CG, St Clair EW, Turkiewicz A, Tchao NK, Webber L, Ding L, Sejismundo LP, Mieras K, Weitzenkamp D, Ikle D, Seyfert-Margolis V, Mueller M, Brunetta P, Allen NB, Fervenza FC, Geetha D, Keogh KA, Kissin EY, Monach PA, Peikert T, Stegeman C, Ytterberg SR, Specks U, RAVE-ITN Research Group: Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010, 363: 221-232. 10.1056/NEJMoa0909905.

Jones RB, Tervaert JW, Hauser T, Luqmani R, Morgan MD, Peh CA, Savage CO, Segelmark M, Tesar V, van Paassen P, Walsh D, Walsh M, Westman K, Jayne DR, European Vasculitis Study Group: Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010, 363: 211-220. 10.1056/NEJMoa0909169.

Hoffman GS, Cid MC, Rendt-Zagar KE, Merkel PA, Weyand CM, Stone JH, Salvarani C, Xu W, Visvanathan S, Rahman MU, Infliximab-GCA Study Group: Infliximab for maintenance of glucocorticosteroid-induced remission of giant cell arteritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007, 146: 621-630.

Salvarani C, Macchioni P, Manzini C, Paolazzi G, Trotta A, Manganelli P, Cimmino M, Gerli R, Catanoso MG, Boiardi L, Cantini F, Klersy C, Hunder GG: Infliximab plus prednisone or placebo plus prednisone for the initial treatment of polymyalgia rheumatica: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007, 146: 631-639.

Baughman RP, Lower EE, Bradley DA, Raymond LA, Kaufman A: Etanercept for refractory ocular sarcoidosis: results of a double-blind randomized trial. Chest. 2005, 128: 1062-1047. 10.1378/chest.128.2.1062.

Mariette X, Ravaud P, Steinfeld S, Baron G, Goetz J, Hachulla E, Combe B, Puéchal X, Pennec Y, Sauvezie B, Perdriger A, Hayem G, Janin A, Sibilia J: Inefficacy of infliximab in primary Sjögren's syndrome: results of the randomized, controlled Trial of Remicade in Primary Sjögren's Syndrome (TRIPSS). Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50: 1270-1276. 10.1002/art.20146.

Melikoglu M, Fresko I, Mat C, Ozyazgan Y, Gogus F, Yurdakul S, Hamuryudan V, Yazici H: Short-term trial of etanercept in Behçet's disease: a double blind, placebo controlled study. J Rheumatol. 2005, 32: 98-105.

Rossman MD, Newman LS, Baughman RP, Teirstein A, Weinberger SE, Miller W, Sands BE: A double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of infliximab in subjects with active pulmonary sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2006, 23: 201-208.

Sankar V, Brennan MT, Kok MR, Leakan RA, Smith JA, Manny J, Baum BJ, Pillemer SR: Etanercept in Sjögren's syndrome: a twelve-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50: 2240-2245. 10.1002/art.20299.

Wegener's Granulomatosis Etanercept Trial (WGET) Research Group: Etanercept plus standard therapy for Wegener's granulomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2005, 352: 351-361.

Martínez-Taboada VM, Rodríguez-Valverde V, Carreño L, López-Longo J, Figueroa M, Belzunegui J, Mola EM, Bonilla G: A double-blind placebo controlled trial of etanercept in patients with giant cell arteritis and corticosteroid side effects. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008, 67: 625-630.

Ramos-Casals M, García-Hernández FJ, de Ramón E, Callejas JL, Martínez-Berriotxoa A, Pallarés L, Caminal-Montero L, Selva-O'Callaghan A, Oristrell J, Hidalgo C, Pérez-Alvarez R, Micó ML, Medrano F, Gómez de la Torre R, Díaz-Lagares C, Camps M, Ortego N, Sánchez-Román J, BIOGEAS Study Group: Off-label use of rituximab in 196 patients with severe, refractory systemic autoimmune diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010, 28: 468-476.

Terrier B, Amoura Z, Ravaud P, Hachulla E, Jouenne R, Combe B, Bonnet C, Cacoub P, Cantagrel A, de Bandt M, Fain O, Fautrel B, Gaudin P, Godeau B, Harlé JR, Hot A, Kahn JE, Lambotte O, Larroche C, Léone J, Meyer O, Pallot-Prades B, Pertuiset E, Quartier P, Schaerverbeke T, Sibilia J, Somogyi A, Soubrier M, Vignon E, Bader-Meunier B, Mariette X, Gottenberg JE, Club Rhumatismes et Inflammation: Safety and efficacy of rituximab in systemic lupus erythematosus: results from 136 patients from the French AutoImmunity and Rituximab registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62: 2458-2466. 10.1002/art.27541.

Dixon WG, Watson K, Lunt M, Hyrich KL, Silman AJ, Symmons DP, British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register: Rates of serious infection, including site-specific and bacterial intracellular infection, in rheumatoid artritis patients receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54: 2368-2376. 10.1002/art.21978.

Galloway JB, Hyrich KL, Mercer LK, Dixon WG, Fu B, Ustianowski AP, Watson KD, Lunt M, BSRBR Control Centre Consortium, Symmons DP, on behalf of the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register: Anti-TNF therapy is associated with an increased risk of serious infections in patients with rheumatoid artritis especially in the first 6 months of treatment: updated results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register with special emphasis on risks in the elderly. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011, 50 (1): 124-131. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq242.

Dixon WG, Carmona L, Finckh A, Hetland ML, Kvien TK, Landewe R, Listing J, Nicola PJ, Tarp U, Zink A, Askling J: EULAR points to consider when establishing, analysing and reporting safety data of biologics registers in rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010, 69: 1596-1602. 10.1136/ard.2009.125526.

Gürcan HM, Keskin DB, Stern JN, Nitzberg MA, Shekhani H, Ahmed AR: A review of the current use of rituximab in autoimmune diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009, 9: 10-25. 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.10.004.

Nam JL, Winthrop KL, van Vollenhoven RF, Pavelka K, Valesini G, Hensor EM, Worthy G, Landewé R, Smolen JS, Emery P, Buch MH: Current evidence for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review informing the EULAR recommendations for the management of RA. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010, 69: 976-986. 10.1136/ard.2009.126573.

Tubach F, Salmon D, Ravaud P, Allanore Y, Goupille P, Bréban M, Pallot-Prades B, Pouplin S, Sacchi A, Chichemanian RM, Bretagne S, Emilie D, Lemann M, Lortholary O, Mariette X, Research Axed on Tolerance of Biotherapies Group: Risk of tuberculosis is higher with anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody therapy than with soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor therapy: The three-year prospective French Research Axed on Tolerance of Biotherapies registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60: 1884-1894. 10.1002/art.24632.

Askling J, Fored CM, Brandt L, Baecklund E, Bertilsson L, Feltelius N, Cöster L, Geborek P, Jacobsson LT, Lindblad S, Lysholm J, Rantapää-Dahlqvist S, Saxne T, van Vollenhoven RF, Klareskog L: Time-dependent increase in risk of hospitalisation with infection among Swedish RA patients treated with TNF antagonists. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007, 66: 1339-1344. 10.1136/ard.2006.062760.

Dixon WG, Symmons DP, Lunt M, Watson KD, Hyrich KL, British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register Control Centre Consortium, on behalf of the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register: Serious infection following anti-tumor necrosis factor _ therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: lessons from interpreting data from observational studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56: 2896-2904. 10.1002/art.22808.

Carmona L, Descalzo MA, Perez-Pampin E, Ruiz-Montesinos D, Erra A, Cobo T, Gómez-Reino JJ, BIOBADASER and EMECAR Groups: All-cause and cause-specific mortality in rheumatoid arthritis are not greater than expected when treated with tumour necrosis factor antagonists. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007, 66: 880-885. 10.1136/ard.2006.067660.

Bongartz T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, Buchan I, Matteson EL, Montori V: Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid artritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006, 295: 2275-2285. 10.1001/jama.295.19.2275.

Listing J, Strangfeld A, Kary S, Rau R, von Hinueber U, Stoyanova-Scholz M, Gromnica-Ihle E, Antoni C, Herzer P, Kekow J, Schneider M, Zink A: Infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologic agents. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52: 3403-3412. 10.1002/art.21386.

Curtis JR, Patkar N, Xie A, Martin C, Allison JJ, Saag M, Shatin D, Saag KG: Risk of serious bacterial infections among rheumatoid artritis patients exposed to tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56: 1125-1133. 10.1002/art.22504.

Doran MF, Crowson CS, Pond GR, O'Fallon WM, Gabriel SE: Frequency of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with controls: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46: 2287-2293. 10.1002/art.10524.

Doran MF, Crowson CS, Pond GR, O'Fallon WM, Gabriel SE: Predictors of infection in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46: 2294-2300. 10.1002/art.10529.

Lacaille D, Guh DP, Abrahamowicz M, Anis AH, Esdaile JM: Use of nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and risk of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 59: 1074-1081. 10.1002/art.23913.

Gottenberg JE, Ravaud P, Bardin T, Cacoub P, Cantagrel A, Combe B, Dougados M, Flipo RM, Godeau B, Guillevin L, Le Loët X, Hachulla E, Schaeverbeke T, Sibilia J, Baron G, Mariette X, AutoImmunity and Rituximab registry and French Society of Rheumatology: Risk factors for severe infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with rituximab in the autoimmunity and rituximab registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62: 2625-2632. 10.1002/art.27555.

BIOGEAS. [http://www.biogeas.es]

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank David Buss for his editorial assistance.

The Biogeas Study Group:

The members of the Spanish Study Group of Biological Agents in Autoimmune Diseases (BIOGEAS) of the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine (SEMI) are as follows:

M. Ramos-Casals (Coordinator, Hospital Clinic, Barcelona); M.M. Ayala (Hospital Carlos Haya, Málaga); M.J. Barragán-González (Hospital Valle del Nalón, Asturias); X. Bosch (Hospital Clinic, Barcelona); A. Bové (Hospital Clinic, Barcelona); P. Brito-Zerón (Hospital Clinic, Barcelona); G. Calvo (Hospital Clinic, Barcelona); J.L. Callejas (Hospital San Cecilio, Granada); L. Caminal-Montero (Hospital Central Asturias); M.T. Camps (Hospital Carlos Haya, Málaga); J. Canora-Lebrato (Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada, Madrid); M. J. Castillo-Palma (Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla); A. Colodro (Complejo Hospitalario de Jaen); E. de Ramón (Hospital Carlos Haya, Málaga); C. Díaz-Lagares (Hospital Clínic, Barcelona); M.V. Egurbide (Hospital Cruces, Barakaldo); D. Galiana (Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón); F.J. García Hernández (Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla); A. Gil (Hospital La Paz, Madrid); R. Gómez de la Torre (Hospital San Agustín, Avilés); R. González-León (Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla); C. Hidalgo (Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada); J. Jiménez-Alonso (Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada); A. Martínez-Berriotxoa (Hospital Cruces, Barakaldo); F. Medrano (Hospital Universitario de Albacete); M.L. Micó (Hospital La Fe, Valencia); S. Muñoz (Hospital Clinic, Barcelona); C. Ocaña (Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla); J. Oristrell (Hospital Parc Taulí, Sabadell); N. Ortego-Centeno (Hospital San Cecilio, Granada); L. Pallarés (Hospital Son Dureta, Mallorca); I. Perales-Fraile (Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada, Madrid); M. Pérez de Lis (Hospital Meixoeiro, Vigo); R. Perez-Alvarez (Hospital Meixoeiro, Vigo); J. Rascón (Hospital Son Dureta, Mallorca); S. Retamozo (Hospital Clinic, Barcelona); J.J. Ríos-Blanco (Hospital La Paz, Madrid); A. Robles (Hospital La Paz, Madrid); G. Ruiz-Irastorza (Hospital Cruces, Barakaldo); L. Saez (Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza); G. Salvador (Hospital de Sagunt, Valencia); J. Sánchez-Roman (Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla); A. Selva-O'Callaghan (Hospital Vall d'Hebron, Barcelona); A. Sisó (CAPSE/GESCLINIC, Barcelona); M. J. Soto-Cárdenas (Hospital Puerta del Mar, Cádiz); C. Tolosa (Hospital Parc Taulí, Sabadell); J. Velilla (Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The BIOGEAS Study group has received educational grants from Roche and Abbott supporting the design and maintenance of the webpage [35]. All authors have declared no conflicts of interest. None has received grants from these laboratories or conducted clinical trials with rituximab or etanercept as principal investigators or received honoraria as an Advisory Board member for Roche and Abbott. The financial support of Roche and Abbott is exclusively limited to maintaining the BIOGEAS webpage.

Authors' contributions

CDL, RPA, and MRC initiated the study and contributed to design, statistical analysis, and drafting and revising the manuscript. All authors contributed to data processing, including data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Cándido Díaz-Lagares, Roberto Pérez-Alvarez contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Díaz-Lagares, C., Pérez-Alvarez, R., García-Hernández, F.J. et al. Rates of, and risk factors for, severe infections in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases receiving biological agents off-label. Arthritis Res Ther 13, R112 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3397

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3397