Abstract

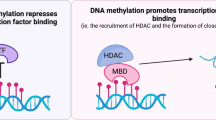

Epigenetic aberrations such as global hypomethylation and gene-specific hypermethylation are key events that underlie tumour development. Such scenarios are brought about by the loss of control of methylation patterns which typically are reversed in neoplasia in comparison to normal states. Despite the methylation process being termed epigenetic, suggesting that it is not a heritable condition, there is strong evidence in mouse models suggesting that epimutations within the germline may provide a mechanism through which methylation variations can be transmissible to offspring. The first half of the review will focus on the nature of methylation-induced gene silencing and transmission of this information through the germline. The latter half will focus on the cause of aberrant DNA methylation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In normal cells, repetitive elements such as long interspersed nucleotide elements (LINE), Alu repeats and satellite sequences, which make up almost half of the entire genome, are methylated. As this contributes largely to the level of global methylation, it is no surprise that these regions are the most drastically affected by hypomethylation, and the stability that the methylation once conferred to the chromosomes is lost. Supporting this is strong evidence to show that global hypomethylation plays a crucial role in causing genomic instability in colorectal carcinogenesis [1]. Such hypomethylation is observed in cancer cells and can be used as an indicator of genomic methylation levels [2]. Alternatively, gene specific hypermethylation is another mechanism which can initiate carcinogenesis. This mechanism of gene silencing is demonstrated by the correlation of methylated promoters with a subsequent decrease of corresponding gene expression. Some examples of genes methylated in cancer are summarised in Table 1. Co-existence of global hypomethylation and gene-specific hypermethylation is common in cancer and will be discussed in more detail later in this review.

Knudson's two-hit hypothesis [3] requires that both alleles of a tumour-suppressing gene be altered for disease progression to occur. Germline mutations commonly represent the first hit of one allele, whilst the second hit typically arises from a sporadic mutation or loss of heterozygosity that affects the second allele (Figure 1a). With the increasing detection of methylated promoters, refinements to Knudson's hypothesis can be made to accommodate epigenetic silencing. The MLH1 gene is widely studied and will be used in the following examples. One such scenario of epigenetic silencing includes methylation acting as the second hit, in unison with a pre-existing mutation on the second allele (Figure 1b) and has been detected on genes such as RB1 [4], VHL [5], MLH1 [6] and BRCA1 [7]. A typical example of this is evident in the colorectal cancer cell line HCT116, which has a truncating mutation in one allele of the p16 gene. The wild-type allele however is subjected to methylation whilst the mutated allele remains unmethylated, showing how co-operatively these two mechanisms can silence genes [8]. Thirdly is a mechanism in which both alleles of a gene become deactivated by methylation. Sporadic cases of colon cancer are frequently the result of methylated MLH1 [9]. Methylation may even act as the first and second hits as illustrated in Figure 1c. As will be discussed shortly, certain individuals possess a silenced MLH1 allele in all cells of the body, and a second event will disrupt the wild-type allele in carcinomas [10].

Alternate mechanisms of Knudson's two-hit hypothesis. Diagram a) illustrates the original hypothesis in which two 'hits" affect both alleles of a particular gene. Diagram b) demonstrates methylation occurring as the second hit in unison with a pre-existing mutation. Diagram c) represents an individual with a soma-wide epimutation. The second allele can then also be lost due to methylation

Inheritance of epimutations

Epimutations have been shown to be transmitted clonally, and the thought that an epimutation can be transferred through the germline has received increasing attention in past years.

Roemer et al. [19] demonstrated that they could induce altered gene expression in mice by nuclear transfer with another cell of different genotype. In doing so, this induced methylation of two genes: major urinary protein (Mup) and olfactory marker protein (Omp). These changes were found to still be in place when the mice reached adulthood, and intriguingly the offspring were found to have increased methylation of the two genes when compared with normal controls. This was the first documented example of epigenetic inheritance, and raised questions as to whether a similar event would be possible in humans.

Ideal candidates were identified by screening populations of people who had the characteristics of a disease, yet lacked any mutation in the genes associated with the disease. Three groups which have done this recognised individuals who were mutation negative for genes associated with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), yet displayed phenotypic similarities to a person with the condition [10, 20–22]. These studies have identified several individuals that show mono-allelic methylation of the MLH1 allele in peripheral blood [20] and additionally in buccal mucosa and hair follicles [10, 21, 22]. As these changes were present soma-wide, they are all indicative of a parental germline change in MLH1 (inherited epimutation) or an event soon after fertilization. Subsequently, the next task was to ascertain whether the methylated allele could be transmitted to offspring and establish a mono-allelic methylation pattern. The transmission of affected alleles from parents to offspring can be monitored by detecting the presence of a polymorphism within the MLH1 promoter. In one family it was found that the methylated paternal allele (present in patient TT) had been passed to a daughter, but it did not attract the methylation as it had in the parent [10]. In a second unrelated family, a male (patient ST) carried a methylated maternal allele, but the allele was not silenced in the mother, or siblings who inherited the corresponding allele [22]. Details of a third family are less detailed; two children of an affected mother (patient VT) possessed normal MLH1 alleles but the status of a third child and the father were not known [10]. Despite neither patient VT nor TT carrying a mutation within a known HNPCC associated gene, they were part of families with histories of the disease. This may suggest that more complex genetic interactions or a gene not linked to MLH1 was causative of their condition rather than a distinct mutation.

The most compelling evidence for transmission of epimutated alleles is shown by the analysis of patient TT's spermatozoa. Following PCR, cloning and hybridization with a methylation-specific probe, 5 of 526 colonies showed a methylated MLH1 promoter. Affected spermatozoa could potentially be transmitted to offspring, rendering them more susceptible to developing disease. Despite only 1% of spermatozoa being affected, this revealed that a) the majority of methylation present is removed during meiosis, and b) that transmission to offspring would be rare, but possible. Cases reported so far have yet to identify the transmission of a methylated allele, so the evidence would support an early epimutational event rather than an inherited predisposition as the cause, although the number of cases studied is small and parental genetic information cannot always be obtained. If indeed the methylated allele was transmitted in that state, the methylation may even be removed early in embryogenesis in the wave of demethylation [23]. Future work may prove epigenetic inheritance using other genes that are commonly affected in disease.

Aberrant methylation patterns

A common characteristic of cancer cells is a reversal of normal methylation patterns; a high level of methylation is observed in specific promoter regions and a global decrease in genomic methylation [24]. It would appear that these features are a cause rather than a consequence of the cancer as alterations can be identified in the early stages of cancer development. For this reason, the mechanism which regulates the methylation process has been highly sought after, yet remains elusive. Several facets which may affect the normal functioning of methylation controlled gene regulation will be discussed here.

DNMT over-expression

Among the most common explanations for the disturbance of regular methylation patterns is the up-regulation of the methyltransferase enzymes. On numerous occasions it has been demonstrated that DNMT levels are elevated in several diverse forms of cancer such as leukaemia [25], endometrial cancer [26] and lung cancer [27]. It could be argued that the down-regulation of maintenance methylation by DNMT1 may lead to hypomethylation, whilst simultaneous up-regulation of the de-novo methyltransferases DNMT3a and 3b could account for the increase in aberrantly methylated promoters. Kimura et al. [28] showed that DNMT1 maintenance methyltransferase expression was not correlated with the extent of DNA hypomethylation in transitional cell carcinomas; however, there was a decrease of DNMT1 expression relative to cell proliferation. Addressing the hypermethylation of certain promoters, it was shown that DNMT3b levels were higher than corresponding normal tissue, although DNMT3a levels were not. While it seems a likely explanation in this scenario, it is not always so straightforward. Observations include simultaneous up- and down-regulation of de novo (DNMT3a and 3b) and maintenance (DNMT1) transferases, and the level of expression of the methyltransferases is sometimes variable within the same cell type [29].

Doubt also surrounds whether over-expression of methyltransferases is responsible for hypermethylation. Eads et al. [30] showed that the expression levels of DNMT1, 3a and 3b did not correlate with the frequency or extent of hypermethylation of APC, ESR1, p16 or MLH1 in colorectal adenocarcinomas. Whilst the methyltransferases were up-regulated when normalised with β-actin and an RNA polymerase large subunit, they were not significantly up-regulated when normalised with proliferation-dependant H4F2 or PCNA. This suggests that although the methyltransferase levels appear to be increased in many cell types, they may in fact not be when they are normalised with other proliferation-dependant genes.

Amid the evidence of altered levels and variations of expression levels, it would not seem logical that simple up-regulation or down-regulation of one form of methyltransferase would cause site-specific hypermethylation in parallel with a global decrease in methylation, but rather a co-ordinated alteration between de novo and maintenance forms to explain the aberrant methylation state.

Subtle CpG island differences

It is evident that some CpG islands are more often affected than others by methylation, supported by the observation that a cluster of genes is frequently hypermethylated in several types of cancer cells [24]. It is no surprise that these genes are heavily involved in the maintenance of genomic integrity, tumour suppression and metastasis, and that these promoters are unaffected in normal tissue. An example of such is the well characterised MLH1 gene in bowel cancer syndromes. This gene is one of four genes which confer a higher susceptibility to HNPCC, yet MLH1 is the only one of the four which becomes methylated.

It would seem reasonable to suggest that some CpG islands may be more likely to succumb to methylation based on CpG island size, GC content, CpG frequency, chromosomal location or promoter association. An experiment by Feltus et al. [31] in 2003 examined the methylation state of several CpG islands in cells over-expressing DNMT1. The majority of the CpG islands tested were resistant to methylation, but a small proportion (3.8%) were found to be hypermethylated by DNMT1. Using this information they identified seven sequence patterns that were capable of discriminating between methylation prone and resistant islands with a success rate of 87%. These sequences would appear to confer some kind of susceptibility or resistance to methylation, possibly similar to the situation in which a non-methylated imprinted allele is resistant to methylation.

In this study, the number of methylated CpG islands may have been biased, due to the over-expression of the maintenance methyltransferase rather than the de novo forms. Therefore the hypermethylated regions in the study are in essence DNMT1 susceptible regions, and it is possible that the number of methylated islands would be higher if de novo methyltransferases were over-expressed. Nonetheless, this study has shown that no particular characteristic such as CpG frequency or island size affects methylation susceptibility, but more so a subset of DNA sequences which may attract or repel methylation. In terms of initiating hypermethylation, these sequences alone will not define the methylation status of a particular gene, as non-methylated regions in normal tissue will also have the same sequence.

DNA demethylation

The issue of DNA demethylation is a major unknown in the field of epigenetics. There has been some debate that still continues over the presence and existence of DNA demethylating enzymes. A demethylating enzyme has been uncovered, but this acts on histones rather than DNA [32]. The most controversy surrounds the MBD2 gene, with one group claiming it has DNA demethylating properties [33–35] whilst others continue to find that it acts as a transcriptional repressor [36–38]. Much work has been performed involving the gene and there are numerous reports that support each side of the debate that will not be discussed here. For details of these, see references [33–38], in particular reference 33, in which supporters of MBD2's demethylase action address issues raised by others suggesting MBD2 is a transcriptional repressor.

At present, the identification of a bona fide demethylase is yet to occur; however, should a candidate be recognised, it will no doubt trigger enormous interest in the particular gene's role in cancer.

Dietary factors, including folate metabolism

There are vast amounts of evidence that nutrition obtained from dietary components has a major influence on individual health status, and there are at least two pathways with which nutrient intake can affect methylation, as reviewed in [39], and more recently [40]. The first of these simply states that the supply of nutrients affects the supply of methyl groups required for methylation. Numerous dietary components are known to influence DNA methylation status, and folate, choline and vitamin B12 feature highly in the literature. Various forms of folate are converted into intermediates that are ultimately converted to S-adenosyl-methionine, the chemical substrate with which the methyltransferase enzymes obtain methyl groups for attachment to the DNA [41]. The precise role of folate and the effects of its absence are complex (for a review see reference [42]), and its importance is due to its function as a precursor methyl-donor. Vitamin B12 is a co-factor for many enzymatic processes leading to the methylation of DNA. Rats fed a diet deficient in B12, but not severe enough to cause illness, were observed to have hypomethylated genomic DNA in colon tissue in comparison to appropriate controls, illustrating that a vitamin deficient diet can restrict DNA methylation.

The second mechanism in which diet can influence methylation relies on the effects of trace dietary components interfering with methyltransferase processes. A selenium deficiency has been shown to cause DNA hypomethylation in rat colon DNA, while prolonged cadmium exposure also initiates hypomethylation followed by hypermethylation, suggesting that a feedback mechanism is involved [43]. In the same study, it was suggested that cadmium inhibited the methyltransferases via an interaction with the DNA binding domain rather than the catalytic domain. Nickel [44] and alcohol [45] have also been observed to affect DNMT activity, although the precise mechanism of this is not understood.

Methylation spreading

The expansion of existing methylation to cover neighbouring non-methylated sites is another hypothesis to explain aberrantly silenced genes.

An experiment by Tollefsbol & Hutchinson [46] has shown that using synthetic oligonucleotides, pre-existing methylation was able to spread to neighbouring CpG islands. It was found that this pseudo-DNA with partial CpG methylation was more likely to undergo de novo methylation on non-affected CpGs than a control without pre-existing methylation. This would suggest that the methylation was required for the methyltransferases to recognise the DNA and spread the methylation. Furthermore, mammalian methyltransferases were the only proteins necessary to induce this state, eliminating the notion that other factors are required for the expansion.

These results provide evidence which supports the spreading of methylation from ordinarily methylated DNA regions to areas which would not usually be methylated. The precise role that this method plays in disease initiation is not known, and methylation spreading has a weaker justification for the aberrant methylation observed in cancer, particularly global hypomethylation. However, if the spreading of methylation to normally unaffected regions occurs in conjunction with another mechanism such as down-regulation of maintenance methylation, it could provide a clearer pathway in which aberrant disease-causing methylation patterns arise.

Conclusion

Epimutation of several genes has been shown to cause disease, and is equivalent to mutations within the same gene, but is a reversible trait. Inheritance of epimutations is an interesting facet of genetics, which may possibly play a role in a small percentage of cancer cases. There is evidence of its occurrence in mammals, yet definite proof of its existence in humans is yet to be demonstrated.

With regards to the regulation of methylation, the five mechanisms discussed each provide a possible explanation for aberrant DNA methylation. However, there does not seem to be one theory that can conclusively account for the abnormal methylation patterns in cancer, namely localised hypermethylation and genome-wide hypomethylation. A combination of events such as any of those discussed above with other environmental and other unknown genetic factors may have a cumulative effect on abnormal DNA methylation.

References

Matsuzaki K, Deng G, Tanaka H, Kakar S, Miura S, Kim YS: The relationship between global methylation level, loss of heterozygosity, and microsatellite instability in sporadic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2005,11(24):8564–8569. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0859

Weisenberger DJ, Campan M, Long TI, Kim M, Woods C, Fiala E, Ehrlich M, Laird PW: Analysis of repetitive element DNA methylation by MethyLight. Nucleic Acid Res 2005, 33: 6823–6836. 10.1093/nar/gki987

Knudson A: Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1971, 68: 820–823. 10.1073/pnas.68.4.820

Ohtani-Fujita N, Dryja TP, Rapaport JM, Fujita T, Matsumura S, Ozasa K, Watanabe Y, Hayashi K, Maeda K, Kinoshita S, Matsumura T, Ohnishi Y, Hotta Y, Takahashi R, Kato MV, Ishizaki K, Sasaki MS, Horsthemke B, Minoda K, Sakai T: Hypermethylation in the retinoblastoma gene is associated with unilateral, sporadic retinoblastoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1997, 98: 43–49. 10.1016/S0165-4608(96)00395-0

Prowse AH, Webster AR, Richards FM, Richard S, Olschwang S, Resche F, Affara NA, Maher ER: Somatic inactivation of the VHL gene in Von Hippel-Lindau disease tumours. Am J Hum Genet 1997, 60: 765–771.

Herman JG, Umar A, Polyak K, Graff JR, Ahuja N, Issa JP, Markowitz S, Willson JK, Hamilton SR, Kinzler KW, Kane MF, Kolodner RD, Vogelstein B, Kunkel TA, Baylin SB: Incidence and functional consequences of hMLH1 promoter hypermethylation in colorectal carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998, 95: 6870–6875. 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6870

Geisler JP, Rathe JA, Manahan KJ, Geisler HE: Methylation: a second hit in the two-hit hypothesis. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2003, 24: 361.

Myohanen SK, Baylin SB, Herman JG: Hypermethylation can selectively silence individual p16ink4A alleles in neoplasia. Cancer Res 1998, 58: 591–593.

Furukawa T, Konishi F, Masubuchi S, Shitoh K, Nagai H, Tsukamoto T: Densely methylated MLH1 promoter correlates with decreased mRNA expression in sporadic colorectal cancers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2002, 35: 1–10. 10.1002/gcc.10100

Suter CM, Martin DI, Ward RL: Germline epimutation of MLH1 in individuals with multiple cancers. Nat Genet 2004, 36: 497–501. 10.1038/ng1342

Brucher BL, Geddert H, Langner C, Hofler H, Fink UR, Siewert J, Sarbia M: Hypermethylation of hMLH1, HPP1, p14 (ARF), p16 (INK4A) and APC in primary adenocarcinomas of the small bowel. Int J Cancer 2006, in press.

Lee S, Hwang KS, Lee HJ, Kim JS, Kang GH: Aberrant CpG island hypermethylation of multiple genes in colorectal neoplasia. Lab Invest 2004, 84: 884–893. 10.1038/labinvest.3700108

Yanokura M, Banno K, Susumu N, Kawaguchi M, Kuwabara Y, Tsukazaki K, Aoki D: Hypemethylation in the p16 promoter region in the carcinogenesis of endometrial cancer in Japanese patients. Anticancer Res 2006, 26: 851–856.

Dhawan D, Hamdy F, Rehman I, Patterson J, Cross S, Feeley K, Stephenson Y, Meuth M, Catto J: Evidence for the early onset of aberrant promoter methylation in urothelial carcinoma. J Pathol 2006, in press.

Bianco T, Chenevix-Trench G, Walsh DC, Cooper JE, Dobrovic A: Tumour specific distribution of BRCA1 promoter region methylation supports a pathogenic role in breast and ovarian cancer. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21: 147–151. 10.1093/carcin/21.2.147

Ma X, Yang Q, Wilson KT, Kundu N, Meltzer SJ, Fulton AM: Promoter methylation regulates cyclooxygenase expression in breast cancer. Breast Cancer research 2004, 6: R316-R321. 10.1186/bcr793

Cheng CW, Wu PE, Yu JC, Huang CS, Yue CT, Wu CW, Shen CY: Mechanisms of inactivation of E-cadherin in breast carcinoma: modification of the two hit hypothesis of tumour suppressor gene. Oncogene 2001, 20: 3814–3823. 10.1038/sj.onc.1204505

Fujii H, Biel MA, Zhou W, Weitzman SA, Baylin SB, Gabrielson F: Methylation of the HIC-1 candidate tumour suppressor gene in human breast cancer. Oncogene 1998, 16: 2159–2164. 10.1038/sj.onc.1201976

Roemer I, Reik W, Dean W, Klose J: Epigenetic Inheritance in the mouse. Curr Biol 1997, 7: 277–280. 10.1016/S0960-9822(06)00124-2

Gazzoli I, Loda M, Garber J, Syngal RD, Kolodner RD: A hereditary non polyposis colorectal carcinoma case associated with hyper methylation of the MLH1 gene in normal tissue and loss of heterozygosity of the unmethylated allele in the resulting microsatellite instability-high tumour. Cancer Res 2002, 62: 3925–3928.

Miyakura Y, Sugano K, Akasu T, Yoshida T, Maekawa M, Saitoh S, Sasaki H, Nomizu T, Konishi F, Fujita S, Moriya Y, Nagai H: Extensive but hemiallelic methylation of hMLH1 promoter region in early-onset sporadic colon cancers with microsatellite instability. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004, 2: 147–156. 10.1016/S1542-3565(03)00314-8

Hitchins M, Williams R, Cheong K, Halani N, Ap Lin V, Packham D, Ku S, Buckle A, Hawkins N, Burn J, Gallinger S, Goldblatt J, Kirk J, Tomlinson I, Scott R, Spigelman A, Suter C, Martin D, Suthers G, Ward R: MLH1 germline epimutations as a factor in Hereditary non polyposis colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2005, 129: 1392–1399. 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.003

Reik W, Dean W, Walter J: Epigenetic reprogramming in mammalian development. Science 2001, 293: 1089–1093. 10.1126/science.1063443

Esteller M, Corn PG, Baylin SB, Herman JG: A gene hypermethylation profile of human cancer. Cancer Res 2001, 61: 3225–3229.

Melki JR, Warnecke P, Vincent PC, Clark SJ: Increased DNA methyltransferase expression in leukemia. Leukemia 1998, 12: 311–316. 10.1038/sj.leu.2400932

Jin F, Dowdy SC, Xiong Y, Eberhardt NL, Podratz KC, Jiang SW: Up-regulation of DNA methyltransferase 3B expression in endometrial cancers. Gynecol Oncol 2005, 96: 531–538. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.10.039

Belinsky SA, Nikula KJ, Baylin SB, Issa JP: Increased cytosine DNA-methyltransferase activity is target-cell-specific and an early event in lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93: 4045–4050. 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4045

Kimura F, Seifert HH, Florl AR, Santourlidis S, Steinhoff C, Swiatkowski S, Mahotka C, Gerharz CD, Schulz WA: Decrease of DNA methyltransferase 1 expression relative to cell proliferation in transitional cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer 2003, 104: 568–578. 10.1002/ijc.10988

De Marzo AM, Marchi VL, Yang ES, Veeraswamy R, Lin X, Nelson WG: Abnormal regulation of DNA methyltransferase expression during colorectal carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 1999, 59: 3855–3860.

Eads CA, Danenberg KD, Kawakami K, Saltz LB, Danenberg PV, Laird PW: CpG island hypermethylation in human colorectal tumours is not associated with DNA methyltransferase overexpression. Cancer Res 1999, 59: 2302–2306.

Feltus FA, Lee EK, Costello JF, Plass C, Vertino PM: Predicting aberrant CpG island methylation. Proc Natl Acad of Sci USA 2003, 100: 12253–12258. 10.1073/pnas.2037852100

Shi Y, Lan F, Matson C, Mulligan P, Whetstine JR, Cole PA, Casero RA, Shi Y: Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell 2004, 119: 941–953. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.012

Detich N, Theberge J, Szyf M: Promoter-specific activation and demethylation by MBD2/demethylase. J Biol Chem 2002, 277: 35791–35794. 10.1074/jbc.C200408200

Szyf M, Bhattacharya SK: Measuring DNA demethylase activity in vitro. Methods Mol Biol 2002, 200: 155–161.

Bhattacharya SK, Ramchandani S, Cervoni N, Szyf M: A mammalian protein with specific demethylase activity for mCpG DNA. Nature 1999, 397: 579–583. 10.1038/17533

Ng HH, Zhang Y, Hendrich B, Johnson CA, Turner BM, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Reinberg D, Bird A: The methyl-CpG binding protein MBD2 is a transcriptional repressor belonging to the MeCP1 fraction of histone deactylase complexes. Nat Genet 1999, 23: 58–61.

Boeke J, Ammerpohl O, Kegel S, Moehren U, Renkawitz R: The minimal repression domain of MBD2b overlaps with the methyl-CpG-binding domain and binds directly to Sin3A. J Biol Chem 2000, 275: 34963–34967. 10.1074/jbc.M005929200

Wade PA, Gegonne A, Jones PL, Ballestar E, Aubry F, Wolffe AP: Mi-2 complex couples DNA methylation to chromatin remodelling and histone deacetylation. Nat Genet 1999, 23: 62–66.

Liu L, Wylie RC, Andrews LG, Tollefsbol TO: Aging, cancer and nutrition: the DNA methylation connection. Mech Ageing Dev 2003, 124: 989–998. 10.1016/j.mad.2003.08.001

McCabe DC, Caudill MA: DNA methylation, genomic silencing and links to nutrition and cancer. Nutr Rev 2005, 63: 183–195. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2005.tb00136.x

Wu JC, Santi DV: On The mechanism and inhibition of DNA cytosine methyltransferases. Prog Clin Biol Res 1985, 198: 119–129.

Kim YI: Folate and DNA methylation: a mechanistic link between folate deficiency and colorectal cancer? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004, 13: 511–519.

Takiguchi M, Achanzar WE, Qu W, Li G, Waalkes MP: Effects of cadmium on DNA-(cytosine-5) methyltransferase activity and DNA methylation status during cadmium-induced cellular transformation. Exp Cell Res 2003, 286: 355–365. 10.1016/S0014-4827(03)00062-4

Costa M, Davidson TL, Chen H, Ke Q, Zhang P, Yan Y, Huang , Kluz T: Nickel carcinogenesis: epigenetics and hypoxia signalling. Mutat Res 2005, 592: 79–88.

Bönsch D, Lenz B, Fiszer R, Frieling H, Kornhuber J, Bleich S: Lowered DNA methylatransferase (DNMT-3b) mRNA expression is associated with genomic DNA hypermethylation in patients with chronic alcoholism. In desktop folder.

Tollefsbol TO, Hutchison CA: Control of methylation spreading in synthetic DNA sequences by the murine DNA methyltransferase. J Mol Biol 1997, 269: 494–504. 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1064

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Hunter Medical Research Institute and the NBN Childhood Cancer Group for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mossman, D., Scott, R.J. Epimutations, Inheritance and Causes of Aberrant DNA Methylation in Cancer. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 4, 75 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1186/1897-4287-4-2-75

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1897-4287-4-2-75