Abstract

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumanii are important nosocomial pathogens with wide intrinsic resistance. However, due to the dissemination of the acquired resistance mechanisms, such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) and metallo beta-lactamase (MBL) production, multidrug resistant strains have been isolated more often.

Case presentation

We report a case of a Hungarian tourist, who was initially hospitalized in Egypt and later transferred to Hungary. On the day of admission PER-1-producing P. aeruginosa, PER-1 producing A. baumannii, SHV-5-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and VIM-2-producing P. aeruginosa isolates were subcultured from the patient's samples in Hungary. Comparing the pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) patterns of the P. aeruginosa strains from the patient to the P. aeruginosa strains occurring in this hospital, we can state that the PER-1-producing P. aeruginosa and VIM-2-producing P. aeruginosa had external origin.

Conclusion

This is the first report of PER-1-producing P. aeruginosa,and PER-1-producing A. baumanii s trains in Hungary. This case highlights the importance of spreading of the beta-lactamase-mediated resistance mechanisms between countries and continents, showing the importance of careful screening and the isolation of patients arriving from a different country.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumanii are very important nosocomial pathogens mainly in intensive care units, being responsible for various types of infections with more and more limited therapeutic options [1].

The P. aeruginosa have significant intrinsic resistance to antibiotics [2]. Therefore, the antipseudomonal beta-lactams such as ticarcillin, piperacillin, ceftazidime, cefepime, aztreonam, and the carbapenems have an important therapeutic value. Three mechanisms of beta-lactam resistance are predominant: production of beta-lactamases, loss of outer membrane proteins and up-regulation of efflux pumps. Most strains of P. aeruginosa which are resistant to third-generation cephalosporins produce a chromosomally mediated molecular class C beta-lactamase, the AmpC enzyme [2]. However, acquired beta-lactamases encoded by mobile genetic elements are important resistance mechanism in P. aeruginosa and in Acinetobacter spp. as well. Acquired resistance to beta-lactams can lead to therapeutic failure, especially when it is associated with resistance to other classes of drugs, such as aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones. Among these enzymes acquired, PER (Pseudomonas extended resistance), a class A extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL), occurring less frequently has clinical importance by conferring resistance to oxyimino beta-lactams [3]. Poor outcome as a result of infection caused by PER-1 producers has been reported [4]. The also acquired metallo beta-lactamases (MBLs) of molecular class B can cause resistance to all beta-lactams except monobactam. The genes of MBLs are usually part of class I integron together with gene cassettes encoding resistance genes. Several types of MBL enzymes have been identified in P. aeruginosa among which the VIM-type enzymes appear to be the most prevalent [5].

Here we report the first detection of PER-producing P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii isolates and VIM-producing P. aeruginosa in Hungary from a patient, who was hospitalized in Egypt and transferred to Hungary. This work illustrates the dissemination of bacteria carrying PER-type ESBL and VIM-type MBL enzymes.

Case presentation

In April, 2006 a 53-year-old Hungarian tourist was involved in a severe terror-attack in Egypt. He was initially hospitalized because of his burn, mechanical injuries and sepsis syndrome in Egypt. Five days later he was transferred in comatose, hypoxic and hypothermic condition to the Burn Unit of State Health Center, Budapest, Hungary. On the day of admission, bacterial cultures taken from burn wound. Based on the different colony morphology and antibiotic susceptibility patterns three different P. aeruginosa strains – an ESBL-producing P. aeruginosa (PA1), an imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa (PA2), an MBL-producing P. aeruignosa (PA3), were observed and furthermore ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae (ESBL-KP), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Enterococcus faecalis (EF) were isolated. Next day ESBL-producing A. baumanii (ESBL-AB) and PA2 were cultured from the patient's canul. During his hospitalization from his nose PA1, ESBL-AB, ESBL-KP, MRSA, from his throat PA1, ESBL-AB, ESBL-KP, from his trachea PA3, ESBL-AB, ESBL.KP,-MRSA and from his wound PA1, PA3, ESBL-AB, ESBL-KP, MRSA and EF were isolated. Blood cultures were taken nine occasions and PA1, ESBL-KP, MRSA and EF were subcultured. The patient received adequate supportive treatment and empirically cefepime, subsequently meropenem and vancomycin were administered intravenously at high dosage. The aminoglycosides were synergy resistant. On the 8th day of the hospitalization in Hungary the patient died.

The isolates were identified by VITEK 2 (BioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France). On a routine antibiogram synergy was observed between amoxycillin/clavulanic acid and cefepime or ceftazidime disks ( Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom) in K. pneumoniae and in A. baumanii strains but no synergy was observed in P. aeruginosa strains. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of the antimicrobial agents were determined by E-test (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) and by using the interpretative criteria of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [6]. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of the SpeI-digested (New England Biolab, Beverly, MA) genomic DNA of P. aeruginosa was performed and analyzed as described previously [7]. Isoelectric focusing (IEF) was performed, as described previously [8]. In the PCR assays primers specific to blaTEM [9], blaSHV [9], blaPER [10], blaOXAs [11], blaIMP, blaVIM and blaclassI genes [12] were used. The nucleotide sequences were determined using the ABI 3100 Genetic Analyzers (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Sequences were analyzed using NCBI BLAST search.

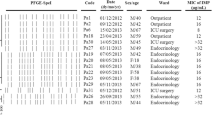

Three different antibiotic susceptibility patterns were observed in P. aeruginosa strains isolated from the patient on the day of admission (Table 1). All of them were resistant to cephalosporins. The PA1 P. aeruginosa strain was sensitive only to carbapenems, the other P. aeruginosa strain (PA2) was sensitive only to meropenem and both PA1 and PA2 were resistant to all the other tested antibiotics. The third P. aeruginosa (PA3) strain was sensitive to aztreonam and netilmicin and resistant to the all cephalosporins and carbepenems. However, the imipenem MIC value decreased in the presence of EDTA from > 256 to 12 μg/ml suggesting the presence of an MBL enzyme. The A. baumanii isolate was resistant to all cephalosporins and aztreonam, but the ceftazidime and cefotaxime MIC values decreased in the presence of clavulanic acid suggesting the presence of an ESBL enzyme. The K. pneumoniae strain had also ESBL phenotype based on the MIC values and it was sensitive to carbapenems, amikacin and ciprofloxacin as well.

The PCR and sequencing results are summarized in Table 2. TEM-1 genes were identified in A. baumanii and K. pneumoniae. OXA genes were recognized in PA1 and PA3 strains. PER-1 genes were found in PA1 and A. baumanii isolates and SHV-5 was found in K. pneumoniae. Only the PA3 isolate harbored the VIM-2 gene. The OXA-10 and VIM-2 genes were located on the same class I integrons, as the sequencing result of class I integron showed.

According to IEF test results, all the isolates contained β-lactamases. Isoelectric focusing confirmed the expression of PER-1 (pI 5.3), TEM-1 (pI 5.4), OXA-1 (pI 7.4), OXA-10 (pI 6.1), SHV-5 (pI 8.2), VIM-2 (pI 5.3) and the chromosomal AmpC cephalosporinase (pI 8 or > 8.5) enzymes in the different strains (Table 2).

The three P. aeruginosa isolates, PA1, PA2 and PA3, showed three different PFGE patterns (data not presented) suggesting that they belonged to different clones (Table 2). Comparing these PFGE patterns to six other P. aeruginosa strains occurring in this Hungarian hospital during the same period, no similarity was found suggesting the external origin of PA1, PA2 and PA3.

Discussion

Based on the antibiotic susceptibilities, IEF and the sequencing result we can state that the PA1 strain and the A. baumanii strain produced PER-1 ESBL enzyme. The A. baumanii strain also produced TEM-1 and the PA1 strain OXA-10 broad-spectrum β-lactamase. The PA2 strain produced only chromosomal AmpC cephalosporinase as suggesting that loss of OprD was responsible for the imipenem resistance. The PA3 strain produced the OXA-1 broad-spectrum β-lactamase and the VIM-2 MBL enzyme. The K. pneumoniae strain produced SHV-5 and TEM-1 enzyme.

According to the type of ESBL enzyme produced by different bacteria species SHV- TEM- and CTX-M type ESBL-producing Klebsiella spp. and Escherichia coli strains have been isolated in Hungary so far [13, 14] – while in Egypt the ESBL phenotype has been observed in K. pneumoniae and CTX-M-type ESBL in E. coli strains [15, 16]. The PER-1 beta-lactamase has been considered to be significant only in Turkey for years [17]. However, the PER-1 beta-lactamase found mainly in P. aeruginosa has been detected in many countries such as Turkey, France, Belgium, Spain, Italy, Poland, Romania, Japan and South Korea until now [10, 18–25]. The PER-1 production in Acinetobacter spp. was observed more often in Turkey and in Korea [4, 17, 26, 27]. According to our knowledge this is the first report of PER-1-producing P. aeruginosa and PER-1-producing A. baumanii in Hungary and since that other strains of PER-1 producing P. aeruginosa have been isolated [28].

Several types of MBL enzymes – IMP-type, VIM-type, SPM-1, GIM-1, SIM-1 – have been identified in P. aeruginosa [5]. The VIM enzymes are the most common in Europe [29]. The VIM-2 enzyme detected in this case has been previously found in several species worldwide and it seems to be the most prevalent allelic form [30–35]. In Hungary VIM-producing P. aeruginosa strains have been isolated but in Egypt MBL-producing strains have not been reported until now [36, 37].

Furthermore the result of the PFGE analysis of the PA1, PA2 and PA3 confirms, that the three P. aeruginosa strains – the PER-1 producing P. aeruginosa (PA1), the OprD-loss P. aeruginosa (PA2) and VIM-2-producing P. aeruginosa (PA3) strains – had external origin and could be transferred from Egypt to Hungary. The PER-1 producing P. aeruginosa and A. baumanii strains disappeared from the hospital, no more infections have been detected with these strains since then.

The emergence and subsequently spread of PER-producing and MBL-producing strains are alarming. Supposing, that these resistance mechanisms might also exist in other countries the dissemination of PER-enzyme could be more prevalent over the world, particularly due to the unsolved problem of routine screening for ESBL-production in P. aeruginosa strains. The CLSI recommendation for screening the ESBL-production in different bacteria species is uncomplete, exist just for Klebsiella spp. and Escherichia coli strains [6].

In conclusion, this work confirms the emergence of PER-1-producing P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii isolate, VIM-2 producing P. aeruginosa strains in Hungary. Furthermore it illustrates the possibility of the inter-country and the inter-continent spread of the beta-lactamase-mediated resistance mechanisms. Our study features the intercontinental spread of antimicrobial resistance, showing the importance of careful screening and the isolation patients arriving from a different country.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's relative for publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

References

Gaynes R, Edwards JR: Overview of nosocomial infections caused by gram-negative bacilli. Clin Infect Dis. 2005, 41 (6): 848-854. 10.1086/432803

Bonomo RA, Szabo D: Mechanisms of multidrug resistance in Acinetobacter species and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Infect Dis. 2006, 43 (Suppl 2): S49-56. 10.1086/504477

Nordmann P, Ronco E, Naas T, Duport C, Michel-Briand Y, Labia R: Characterization of a novel extended-spectrum beta-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993, 37 (5): 962-969.

Vahaboglu H, Coskunkan F, Tansel O, Ozturk R, Sahin N, Koksal I, Kocazeybek B, Tatman-Otkun M, Leblebicioglu H, Ozinel MA, Akalin H, Kocagoz S, Korten V: Clinical importance of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (PER-1-type)-producing Acinetobacter spp. and Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. J Med Microbiol. 2001, 50 (7): 642-645.

Queenan AM, Bush K: Carbapenemases: the versatile beta-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007, 20 (3): 440-458. 10.1128/CMR.00001-07

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI): Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, Approved standard M7-A7. CLSI, Wayne, PA. 2006, 7

Grundmann H, Schneider C, Hartung D, Daschner FD, Pitt TL: Discriminatory power of three DNA-based typing techniques for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Clin Microbiol. 1995, 33 (3): 528-534.

Paterson DL, Rice LB, Bonomo RA: Rapid method of extraction and analysis of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases from clinical strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001, 7 (12): 709-711. 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2001.00348.x

Essack SY, Hall LM, Pillay DG, McFadyen ML, Livermore DM: Complexity and diversity of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains with extended-spectrum beta-lactamases isolated in 1994 and 1996 at a teaching hospital in Durban, South Africa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001, 45 (1): 88-95. 10.1128/AAC.45.1.88-95.2001

Pagani L, Mantengoli E, Migliavacca R, Nucleo E, Pollini S, Spalla M, Daturi R, Romero E, Rossolini GM: Multifocal detection of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing the PER-1 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase in Northern Italy. J Clin Microbiol. 2004, 42 (6): 2523-2529. 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2523-2529.2004

Bert F, Branger C, Lambert-Zechovsky N: Identification of PSE and OXA beta-lactamase genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa using PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002, 50 (1): 11-18. 10.1093/jac/dkf069

Docquier JD, Riccio ML, Mugnaioli C, Luzzaro F, Endimiani A, Toniolo A, Amicosante G, Rossolini GM: IMP-12, a new plasmid-encoded metallo-beta-lactamase from a Pseudomonas putida clinical isolate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003, 47 (5): 1522-1528. 10.1128/AAC.47.5.1522-1528.2003

Toth A, Gacs M, Marialigeti K, Cech G, Fuzi M: Occurrence and regional distribution of SHV-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Hungary. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005, 24 (4): 284-287. 10.1007/s10096-005-1315-9

Damjanova I, Toth A, Paszti J, Bauernfeind A, Fuzi M: Nationwide spread of clonally related CTX-M-15-producing multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains in Hungary. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006, 25 (4): 275-278. 10.1007/s10096-006-0120-4

Bouchillon SK, Johnson BM, Hoban DJ, Johnson JL, Dowzicky MJ, Wu DH, Visalli MA, Bradford PA: Determining incidence of extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in 38 centres from 17 countries: the PEARLS study 2001–2002. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2004, 24 (2): 119-124. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.01.010

Mohamed Al-Agamy MH, El-Din Ashour MS, Wiegand I: First description of CTX-M beta-lactamase-producing clinical Escherichia coli isolates from Egypt. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006, 27 (6): 545-548. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.01.007

Vahaboglu H, Ozturk R, Aygun G, Coskunkan F, Yaman A, Kaygusuz A, Leblebicioglu H, Balik I, Aydin K, Otkun M: Widespread detection of PER-1-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases among nosocomial Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in Turkey: a nationwide multicenter study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997, 41 (10): 2265-2269.

Kolayli F, Gacar G, Karadenizli A, Sanic A, Vahaboglu H: PER-1 is still widespread in Turkish hospitals among Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005, 249 (2): 241-245. 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.06.012

De Champs C, Poirel L, Bonnet R, Sirot D, Chanal C, Sirot J, Nordmann P: Prospective survey of beta-lactamases produced by ceftazidime- resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated in a French hospital in 2000. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002, 46 (9): 3031-3034. 10.1128/AAC.46.9.3031-3034.2002

Naas T, Bogaerts P, Bauraing C, Degheldre Y, Glupczynski Y, Nordmann P: Emergence of PER and VEB extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Acinetobacter baumannii in Belgium. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006, 58 (1): 178-182. 10.1093/jac/dkl178

Miro E, Mirelis B, Navarro F, Rivera A, Mesa RJ, Roig MC, Gomez L, Coll P: Surveillance of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases from clinical samples and faecal carriers in Barcelona, Spain. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005, 56 (6): 1152-1155. 10.1093/jac/dki395

Empel J, Filczak K, Mrowka A, Hryniewicz W, Livermore DM, Gniadkowski M: Outbreak of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections with PER-1 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase in Warsaw, Poland: further evidence for an international clonal complex. J Clin Microbiol. 2007, 45 (9): 2829-2834. 10.1128/JCM.00997-07

Naas T, Nordmann P, Heidt A: Intercountry transfer of PER-1 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii from Romania. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007, 29 (2): 226-228. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.08.032

Yamano Y, Nishikawa T, Fujimura T, Yutsudou T, Tsuji M, Miwa H: Occurrence of PER-1 producing clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Japan and their susceptibility to doripenem. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2006, 59 (12): 791-796.

Lee S, Park YJ, Kim M, Lee HK, Han K, Kang CS, Kang MW: Prevalence of Ambler class A and D beta-lactamases among clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Korea. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005, 56 (1): 122-127. 10.1093/jac/dki160

Yong D, Shin JH, Kim S, Lim Y, Yum JH, Lee K, Chong Y, Bauernfeind A: High prevalence of PER-1 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Acinetobacter spp. in Korea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003, 47 (5): 1749-1751. 10.1128/AAC.47.5.1749-1751.2003

Jeong SH, Bae IK, Kwon SB, Lee K, Yong D, Woo GJ, Lee JH, Jung HI, Jang SJ, Sung KH, Lee SH: Investigation of a nosocomial outbreak of Acinetobacter baumannii producing PER-1 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase in an intensive care unit. J Hosp Infect. 2005, 59 (3): 242-248. 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.09.025

Libisch B, Lepsanovic Z, Krucso B, Muzslay M, Tomanovic B, Nonkovic Z, Mirovic V, Szabo G, Balogh B, Füzi M: Characterization of PER-1 extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates from Hungary and Serbia. [poster]. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007, 13 (Suppl 1): S162-

Fritsche TR, Sader HS, Toleman MA, Walsh TR, Jones RN: Emerging metallo-beta-lactamase-mediated resistances: a summary report from the worldwide SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. Clin Infect Dis. 2005, 41 (Suppl 4): S276-278. 10.1086/430790

Walsh TR, Toleman MA, Hryniewicz W, Bennett PM, Jones RN: Evolution of an integron carrying blaVIM-2 in Eastern Europe: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003, 52 (1): 116-119. 10.1093/jac/dkg299

Wang C, Wang J, Mi Z: Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing VIM-2 metallo-beta-lactamases and carrying two aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes in China. J Hosp Infect. 2006, 62 (4): 522-524. 10.1016/j.jhin.2005.10.002

Yan JJ, Ko WC, Chuang CL, Wu JJ: Metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates in a university hospital in Taiwan: prevalence of IMP-8 in Enterobacter cloacae and first identification of VIM-2 in Citrobacter freundii. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002, 50 (4): 503-511. 10.1093/jac/dkf170

pGuerin F, Henegar C, Spiridon G, Launay O, Salmon-Ceron D, Poyart C: Bacterial prostatitis due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa harbouring the blaVIM-2 metallo-β-lactamase gene from Saudi Arabia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005, 56 (3): 601-602. 10.1093/jac/dki280

Aboufaycal H, Sader HS, Rolston K, Deshpande LM, Toleman M, Bodey G, Raad I, Jones RN: blaVIM-2 and blaVIM-7 carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates detected in a tertiary care medical center in the United States: report from the MYSTIC program. J Clin Microbiol. 2007, 45 (2): 614-615. 10.1128/JCM.01351-06

Pitout JD, Chow BL, Gregson DB, Laupland KB, Elsayed S, Church DL: Molecular epidemiology of metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the Calgary Health Region: emergence of VIM-2-producing isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2007, 45 (2): 294-298. 10.1128/JCM.01694-06

Libisch B, Muzslay M, Gacs M, Minárovits J, Knausz M, Watine J, Ternák G, Kenéz E, Kustos I, Rókusz L, Széles K, Balogh B, Füzi M: Molecular epidemiology of VIM-4 metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas sp. isolates in Hungary. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006, 50 (12): 4220-4223. 10.1128/AAC.00300-06

Libisch B, Watine J, Balogh B, Gacs M, Muzslay M, Szabo G, Fuzi M: Molecular typing indicates an important role for two international clonal complexes in dissemination of VIM-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates in Hungary. Res Microbiol. 2008, 159 (3): 162-8. 10.1016/j.resmic.2007.12.008

Acknowledgements

We thank dr. Katalin Kamotsay for her comments on the manuscript. The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance provided by Natasa Pesti. This work was supported in part by Hungarian Scientific Research Found 48410 and by Foundation of "Budapest Bank for Budapest" 12977-2614/2007/BBB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

LR and ZJ provided clinical care, literature search and edited the manuscript, JS and KK identified the bacteria, performed the antibiotic susceptibility tests, DS carried out the molecular studies, characterized the bacteria and drafted the manuscript, NK drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Dora Szabó, Julia Szentandrássy contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Szabó, D., Szentandrássy, J., Juhász, Z. et al. Imported PER-1 producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa, PER-1 producing Acinetobacter baumanii and VIM-2-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains in Hungary. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 7, 12 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-0711-7-12

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-0711-7-12