Abstract

Background

The polymorphism rs6313 (T102C) has been associated with suicidal behavior in case–control and meta-analysis studies, but results and conclusions remain controversial. The aim of the present study was to examine the association between T102C with suicidal behavior in a case–control study and, to assess the combined evidence – this case–control study and available data from other related studies – we carried out a meta-analysis.

Methods

We conducted a case–control study that included 161 patients with suicide attempts and 244 controls; we then performed a meta-analysis. The following models were evaluated in the meta-analysis: A) C allele vs T allele; B) T allele vs C allele; C) Caucasian population, D) Asian population, and E) suicide attempters with schizophrenia.

Results

We found an association between attempted suicide and control participants for genotype (χ2=6.28, p=0.04, df=2) and allele (χ2=6.17, p=0.01, df=1, OR 1.48 95% IC: 1.08-2.03) frequencies in the case–control study. The meta-analysis, comprising 23 association studies (including the present one), showed that the rs6313 polymorphism is not associated with suicidal behavior for the following comparisons:T allele vs C allele (OR: 1.03; 95% CI 0.93-1.13; p(Z)=0.44); C allele vs T allele: (OR:0.99; 95% CI: 0.90-1.08; p(Z)=0.22); Caucasians (OR:1.09; 95% CI: 0.96-1.23), and Asians (OR:0.96; 95% CI: 0.84-1.09).

Conclusion

Our results showed association between the rs6313 (T102C) polymorphism and suicidal behavior in the case–control study. However, the meta-analysis showed no evidence of association. Therefore, more studies are necessary to determine conclusively an association between T102C and suicidal behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Suicidal behavior is a major health problem worldwide. Several recent studies have been carried out that support a possible relationship between genetic factors and suicidal behavior [1, 2]. Historically, evidence for the involvement of serotonin (5-HT) in suicide originated from findings of low 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid concentration (5-HIIA) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of depressed suicide attempters and in brain stems of completed suicides [3–5]. These studies provided evidence for altered serotonergic neural transmission in the pathogenesis of suicidal behavior [6, 7]. In consequence, genes pertaining to the serotonergic system have been proposed as candidates to establish biological correlates between suicidal behavior and the serotonergic system [8–12].

Fourteen known serotonin receptor subtypes are involved in serotonin action [13]. One candidate gene in the study of suicidal behavior is the gene encoding the serotonin 2A receptor. There is evidence that the density of serotonin 2A receptors is upregulated in parietal cortical regions of depressed suicide victims and this increase has been suggested to be at least partly regulated genetically [14]. The 5HTR2A gene is located on chromosome 13 (13q14-q21); it spans 20 kb and contains 3 exons; more than 200 SNPs have been identified along the gene [13, 15]. Mainly, the polymorphisms A-1438G (rs6311), T102C (rs6313) and His452Tyr (rs6314) have been studied in relation to suicidal behavior. Moreover, a recent report has studied all SNPs in 5HTR2A [16]. One of the most remarkable single nucleotide polymorphisms of the 5HTR2A gene is T102C (rs6313). Several genetic studies have shown an association between 5HTR2A and suicidal behavior [17, 18]. Similarly, this common variant has been studied not only in relation to suicidal behavior, but also in association with other diseases such as schizophrenia [19–21], alcoholism [22], and depression [23].

To our knowledge, up to the present moment, there are no association studies of 5HTR2A and suicidal behavior in the Mexican population. Therefore, we examined the association between 5HTR2A and suicidal behavior in this population. This work focuses on investigating the genetic basis of suicide attempters by assessing the rs6313 genotype. Finally, we used the combined evidence to carry out a meta-analysis of all published data.

Methods

Case–control study

A total of 161 patients were consecutively recruited from the outpatient service of the General Hospital of Comalcalco in the state of Tabasco, Mexico. These patients had attempted suicide between January and December 2011. In addition, 247 unrelated controls participated in this study. They were recruited from the Blood Donor Center of the General Hospital of Comalcalco and from the general population of the Comalcalco city area in the state of Tabasco, México. Subjects were physically healthy on medical evaluation; none manifested psychiatric problems, as assessed in brief interviews by psychiatrists. To reduce ethnic variation and stratification effects, only Mexican subjects descending from Mexican parents and grandparents participated in this study. However, no structured methods were used to assess genetic heterogeneity.

Ethics statement

After they were given a verbal and written explanation of the research objectives, all subjects signed an informed consent to participate in the study; they did not receive any economical remuneration. This study complied with the principles convened in the Helsinki Declaration. In addition, this study was approved by the DAMC-UJAT Ethics and Research Committee (P.O.A. 20110237).

Clinical evaluation

Suicide attempt patients were evaluated by a trained psychiatrist or clinical psychologists with at least a master's degree level, using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-I and II diagnoses, in the Spanish version. We defined suicide attempt as a self-harm behavior with at least some intent to end one’s life [24]. Subjects were excluded when self-injury behaviors were determined to have no suicidal intention or ideation, based on the Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for suicide ideation in the Spanish version [25].

Genotype assays

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using a modified version of the protocol by Lahiri [26]. The 5HTR2A T102C (rs6313) genotypes were analyzed in all patients using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) end-point method. The final volume of the PCR reaction was 5 μL and consisted of 20 ng genomic DNA, 2.5 Fluorescence Labeling (FL) TaqMan Master Mix, and 2.5 FL 20x Assay. The amplification was performed in 96-well plates using the TaqMan Universal Thermal Cycling Protocol. After the PCR end-point was reached, fluorescence intensity was measured with the 7500 Real-Time PCR system using SDS v2.1 software (Applied Biosystems). All genotyping was performed blind to patient outcome. As a quality control in our genotyping analyses we used random blind duplicates.

Statistical analysis

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was tested using Pearson's goodness-of-fit chi-squared test. Chi-squared test or Fisher's Exact test was used to compare genotype and allele frequencies between groups. The power to detect associations given the sample size was analyzed by using the Quanto 1.2 software. The power of the analysis was 0.43 (minor allele frequency= 0.3, type of model: dominant, effect size: 1.5). The level of significance was set at p=0.05.

Meta-analysis

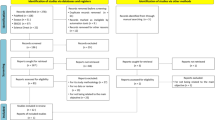

This meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria [27].

Identification and selection of publications

A literature search was performed that covered from 1997 to 2012. Relevant publications were identified using the following search terms in Medline, Ebsco and Web of Science databases: “HTR2A and suicidal behavior”, “HTR2A and suicide”, “rs6313 and suicide”, “5-hydroxytryptamine-receptor 2A” and “serotonin receptor 2A”. These words were combined to retrieve the summaries. The search also implicated the review of the bibliography cited at the end of various research articles to identify additional papers not covered by the electronic search of abstracts. The publications had to fulfill the following selection criteria: (1) to be studies on the relationship between rs6313 and suicidal behavior (attempted, ideation and completed suicide), (2) to be published in peer-reviewed journals, (3) to contain independent data, (4) to be case–control association studies in which the frequencies of three genotypes were clearly stated or could be calculated, (5) the use of healthy individuals as controls, and (6) to provide sufficient data to enable the estimation of an odds ratio with 95% confidence interval.

Two investigators (González-Castro TB and Tovilla-Zárate CA) working independently screened each of the titles, abstracts and full texts to determine their inclusion. The results were compared and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction

The same authors mentioned in the last paragraph carefully extracted the information from all the included publications; they worked in an independent manner and in accordance with the inclusion criteria listed above. The following data were obtained from each of the studies: authors, year of publication, region, number of cases and controls, age, and ethnical origin of the participants. The outcomes of the meta-analysis were built by taking into consideration the following categories: a) exposed sick, b) exposed not-sick, c) not-exposed sick and d) not-exposed not-sick. The “sick” term refers to subjects exhibiting suicidal behavior and the “exposed” term to the allele of risk.

Data analysis

For the meta-analysis procedures, we used the EPIDAT 3.1 program (http://dxsp.sergas.es). This software is freely available for epidemiologic analysis of tabulated data. Data were analyzed with the random-effects model following the reports in the literature [2, 28, 29]. Sample heterogeneity was analyzed with the Dersimonian and Laird’s Q test. Q test results were complemented with graphs to help the visualization of those studies favoring heterogeneity. The results of the meta-analysis are expressed as an odds ratio (OR). To address the problem of publication bias, funnel plots were calculated with the EPIDAT 3.1 software. This plotting standardizes the effect of each of the published studies on the vertical axis and its correspondent precision on the horizontal axis. Finally, a chi-squared (χ2) analysis was used to calculate the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium to assess genotype distribution.

Results

Case–control study

In the present study a total of 161 patients (61 males, 100 females) were recruited; mean age was 25.5 (9.56) years old (range: 14–56 years of age). Control subjects consisted of 244 volunteers (82 males, 162 females); mean age was 33.1 (13.0) years old (range: 14–61 years of age). Both groups (cases p=0.06 and controls p=0.06) showed Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium for the analyzed genetic variability. From the 161 suicide attempters, 11 (7%) exhibited the T102T genotype, 80 (50%) the T102C, and 70 (43%) the C102C type. On the other hand, in the control group, 9 individuals (4%) presented the T102T genotype, 100 (41%) the T102C type, and 135 (55%) the C102C type. We observed significant differences in genotype (χ2=6.28, p=0.04, df=2) and allele (χ2=6.17, p=0.01, df=1, OR 1.48 95% IC: 1.08-2.03) frequencies between patients and the control group.

Meta-analysis study

The selection process in this study is detailed in Figure 1. With regard to the literature search, a total of 397 studies were identified, but only 23 were used in this meta-analysis, including our case–control study [14, 20–23, 30–40]; this involved 2566 cases and 3989 controls (Table 1). In addition, 612 cases from a more recent meta-analysis and 1129 controls were incorporated as well [41]. Overall, the meta-analysis included 13 studies in Caucasian populations, 6 studies comprising Asian populations and 4 from other ethnic origins.

We measured the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in all genotyped populations. Both patients and controls were in equilibrium (p>0.05), with the exception of the control group in Du et al. (p=0.004), Turecki et al. (0.009) and Crawford et al. (0.01) [14, 30, 35], as well as the patients in Zhang et al. (p=0.04) [38]. When we explored all populations in a combined way we still encountered them in equilibrium with p=0.19 and p=0.92 for controls and cases, respectively.

Figure 2 shows the pooled OR derived from all studies indicating a non-significant association of the C allele in the T102C polymorphism with suicidal behavior (Random effects: OR:1.14; 95% CI 0.96-1.35; p(Z)=0.07). We observed heterogeneity in all studies (Q=75.03 df=20; p=<0.0001). The Egger's test provided no evidence of publication bias (t=1.37, df=19; p=0.18) (Figure 3A). Therefore, we carried out a second analysis, which excluded studies based on the heterogeneity curve and sensitivity analysis. As a result, the reports by (Crawford et al. [35], Zhang et al. [38], Du et al. [30], Turecki et al. [14] and ours were excluded. However, we could not find an association either (OR: 1.03; 95% CI 0.93-1.13; p(Z)=0.44).

Given that our results in the association study suggested an association with the T allele, we performed a meta-analysis using the allelic model for this allele (Table 2). We did not encounter any association between the T allele and suicidal behavior (Random effects; OR: 0.87; 95% CI 0.73-1.03; p(Z)=0.07). We also found heterogeneity in all studies (Q=75.03 df=20; p=<0.0001). The Egger's test indicated no evidence of publication bias (t=−1.37, df=19; p=0.18; Figure 3B). A second analysis was performed, which only included studies based on the heterogeneity curve and sensitivity analysis (Random effects: OR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.90-1.08; p(Z)=0.22). The Egger's test gave no evidence of publication bias (t=−0.1726, df=12; p=0.86).

In addition, we performed an analysis in two population groups: Caucasian (Fixed effects; OR: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.03-1.25, Random effects OR: 1.21; 95% CI: 0.97-1.57 with heterogeneity; Egger's test Figure 3C, OR: 1.09; 95% CI: 0.96-1.23 without heterogeneity; Table 3) and Asian (OR: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.84-1.09 without heterogeneity; Egger's test Figure 3D). Again in this case, we could not find any association with suicidal behavior. Finally, in an analysis including only studies of suicide attempt patients with schizophrenia, the results were also negative (Random effects; OR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.79-1.06 without heterogeneity).

Discussion

In this study, we explored the association of the T102C (rs6313) polymorphism of the 5-HTR2A gene with suicidal behavior. First, a case–control study was conducted. Subsequently, we performed a meta-analysis to assess the current evidence of association between rs6313 and suicidal behavior. In the first part, we found an association between rs6313 and suicidal behavioral in a Mexican sample. To our knowledge, this is the first study addressing the genetic association between the T102C allele and suicidal behavior in a Mexican population.

The genetic analysis revealed a slight preponderance of the T allele in the cases group. In 2000, Du et al. described an association between the 102C allele and ideation suicide [30]. Since 2000, growing interest on this issue prompted a variety of studies in Caucasian and Asian populations dealing with 5HTR2A and suicidal behavior. Although many studies have reported this association [21, 22, 33, 42], there are other reports that have not encountered an association of either the T or C allele in rs6313 of 5HTR2A [20, 23, 31, 32, 35, 38, 43] with suicidal behavior. The slight preponderance of the T allele is in agreement with other reports in the literature. In 1999, Tsai et al. [34] reported that the allele frequency of 102T is higher than that of 102C in both patient and control groups. Recently, Saiz et al. [36] found an excess of the 102T allele in a group of 193 patients and a control group of 420 individuals when comparing non-impulsive suicide attempts with impulsive suicide attempts. This evidence suggests that the rs6313 polymorphism of the 5-HTR2A gene may be involved in suicidal behavior. However, no conclusive outcomes have yet been attained. In agreement, our results in the Mexican population suggest that allele 102T of 5HTR2A could be associated with suicidal behavior.

There are several possible explanations for the discrepancies in the results regarding this association. First, there are differences in the populations of patients. For example, Du et al. [30] and other authors [13, 23] have studied patients with major depression and suicidal behavior; Wrzosek et al. studied patients with attempted suicides and alcohol dependence [22]; other studies have analyzed suicidal behavior in patients with schizophrenia [20], and finally, there are studies such as ours that have analyzed only suicide attempters [8, 31, 36]. Second, there are differences in genetic heterogeneity. Several authors have shown that allele frequencies of the T102C polymorphism may be ethnic-dependent [34, 36, 44]. However, our sample was made of a relatively homogenous Mexican population, because only patients of the state of Tabasco with parents and grandfathers born in Tabasco were included in this study. In consequence, we considered necessary to carry out a meta-analysis of all the published evidence concerning rs6313 and suicidal behavior.

In the current meta-analysis we utilized the allelic model and ethnicity groups. There are two previous meta-analyses -the last including 25 studies- that have explored the association between rs6313 and suicidal behavior [41, 45]. Both meta-analyses reported no association between rs6313 and suicidal behavior. However, several additional case–control studies concerning this relationship and using larger samples have been recently reported, but they are not included in the above-mentioned meta-analyses. Therefore, to get a more comprehensive estimation we included our case–control study.

We performed a meta-analysis for the C (OR: 1.14; 95% CI 0.96-1.35) and T (OR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.90-1.08) alleles separately; however, no association was observed. The results suggest no association between rs6313 (T102C) and suicidal behavior. One possibility for this lack of association may lie in the different criteria used in the selection of patients. In addition, samples sizes of several of the studies included in our meta-analysis are in the low range compared with genetic studies for other diseases [7, 46].

There is the possibility that the C allele may be regarded as a factor risk in the Caucasian population, because in a first analysis we observed an association when we considered a fixed effects with heterogeneity. However, we adopted the random effects, which accounts for additional sources of inter-study variation when heterogeneity exists. This model is more conservative than the fixed effects, since the latter assumes the same true genetic effects, whereas the former assumes normally distributed effects and parametrizes inter-studies variation [41]. When we performed a second analysis, in which the studies giving rise to heterogeneity were discarded, no association was observed between rs6313 and suicidal behavior in a Caucasian population. Therefore, future studies on suicidal behavior comprising larger samples are important to determine this association. Similarly, the accuracy of the phenotype definition in the association studies is a relevant issue [41]. However, it is necessary to take into consideration other aspects such as different inheritance patterns and gene X environment interaction [16].

Finally, we recognize some limitations in the present study; 1) the sample size of the case–control study is small and may not have sufficient power to detect an association between suicidal behavior and small effects polymorphism. In relation to our meta-analysis, there are also some considerations to bear in mind: first; included studies were limited to published articles; second, we did not perform sub-analyses including attempted or completed suicide; third, we did not carry out a subgroup analysis based on gender, and fourth, we did not report psychopathologies related to suicide attempters.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we encountered a significant association between the T102C polymorphism and suicidal behavior in a Mexican population. However, this result was not observed in the meta-analysis. Nonetheless, our meta-analysis provides pooled data on a substantial number of cases and controls that may provide a better understanding in the association between rs6313 and suicidal behavior. However, more comprehensive studies and larger samples are necessary to determine conclusively the presence of this association.

Abbreviations

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- DSM-IV:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV

- SA:

-

Suicide attempters

- SC:

-

Suicide completers

- SI:

-

Suicide ideation.

References

Murphy TM, Ryan M, Foster T, Kelly C, McClelland R, O'Grady J, Corcoran E, Brady J, Reilly M, Jeffers A, et al: Risk and protective genetic variants in suicidal behaviour: association with SLC1A2, SLC1A3, 5-HTR1B &NTRK2 polymorphisms. Behav Brain Funct. 2011, 7: 22-10.1186/1744-9081-7-22.

Tovilla-Zarate C, Juarez-Rojop I, Ramon-Frias T, Villar-Soto M, Pool-Garcia S, Medellin BC, Genis Mendoza AD, Narvaez LL, Humberto N: No association between COMT val158met polymorphism and suicidal behavior: meta-analysis and new data. BMC Psychiatry. 2011, 11: 151-10.1186/1471-244X-11-151.

Roy A, Agren H, Pickar D, Linnoila M, Doran AR, Cutler NR, Paul SM: Reduced CSF concentrations of homovanillic acid and homovanillic acid to 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid ratios in depressed patients: relationship to suicidal behavior and dexamethasone nonsuppression. Am J Psychiatry. 1986, 143 (12): 1539-1545.

Traskman L, Asberg M, Bertilsson L, Sjostrand L: Monoamine metabolites in CSF and suicidal behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981, 38 (6): 631-636. 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780310031002.

Asberg M, Traskman L, Thoren P: 5-HIAA in the cerebrospinal fluid. A biochemical suicide predictor?. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976, 33 (10): 1193-1197. 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770100055005.

Savitz JB, Cupido CL, Ramesar RS: Trends in suicidology: personality as an endophenotype for molecular genetic investigations. PLoS Med. 2006, 3 (5): e107-10.1371/journal.pmed.0030107.

Angles MR, Ocana DB, Medellin BC, Tovilla-Zarate C: No association between the HTR1A gene and suicidal behavior: a meta-analysis. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2012, 34 (1): 38-42.

Saiz PA, Garcia-Portilla P, Paredes B, Corcoran P, Arango C, Morales B, Sotomayor E, Alvarez V, Coto E, Florez G, et al: Role of serotonergic-related systems in suicidal behavior: Data from a case–control association study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011, 35 (6): 1518-1524. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.04.011.

Mann JJ, Arango VA, Avenevoli S, Brent DA, Champagne FA, Clayton P, Currier D, Dougherty DM, Haghighi F, Hodge SE, et al: Candidate endophenotypes for genetic studies of suicidal behavior. Biol Psychiatry. 2009, 65 (7): 556-563. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.021.

Benko A, Lazary J, Molnar E, Gonda X, Tothfalusi L, Pap D, Mirnics Z, Kurimay T, Chase D, Juhasz G, et al: Significant association between the C(−1019)G functional polymorphism of the HTR1A gene and impulsivity. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010, 153B (2): 592-599.

Zalsman GIL, Patya M, Frisch A, Ofek H, Schapir L, Blum I, Harell D, Apter A, Weizman A, Tyano S: Association of polymorphisms of the serotonergic pathways with clinical traits of impulsive-aggression and suicidality in adolescents: A multi-center study. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011, 12 (1): 33-41. 10.3109/15622975.2010.518628.

Vang FJ, Lindstrom M, Sunnqvist C, Bah-Rosman J, Johanson A, Traskman-Bendz L: Life-time adversities, reported thirteen years after a suicide attempt: relationship to recovery, 5HTTLPR genotype, and past and present morbidity. Arch Suicide Res. 2009, 13 (3): 214-229. 10.1080/13811110903044328.

Yoon HK, Kim YK: TPH2–703G/T SNP may have important effect on susceptibility to suicidal behavior in major depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009, 33 (3): 403-409. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.12.013.

Turecki G, Briere R, Dewar K, Antonetti T, Lesage AD, Seguin M, Chawky N, Vanier C, Alda M, Joober R, et al: Prediction of level of serotonin 2A receptor binding by serotonin receptor 2A genetic variation in postmortem brain samples from subjects who did or did not commit suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1999, 156 (9): 1456-1458.

Norton N, Owen MJ: HTR2A: association and expression studies in neuropsychiatric genetics. Ann Med. 2005, 37 (2): 121-129. 10.1080/07853890510037347.

Ben-Efraim YJ, Wasserman D, Wasserman J, Sokolowski M: Family-based study of HTR2A in suicide attempts: observed gene, gene x environment and parent-of-origin associations. Mol Psychiatry. 2012, 3 (10): 86-

Correa H, De Marco L, Boson W, Viana MM, Lima VF, Campi-Azevedo AC, Noronha JC, Guatimosim C, Romano-Silva MA: Analysis of T102C 5HT2A polymorphism in Brazilian psychiatric inpatients: relationship with suicidal behavior. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2002, 22 (5–6): 813-817.

Etain B, Rousseva A, Roy I, Henry C, Malafosse A, Buresi C, Preisig M, Rayah F, Leboyer M, Bellivier F: Lack of association between 5HT2A receptor gene haplotype, bipolar disorder and its clinical subtypes in a West European sample. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004, 15 (1): 29-33.

Correa H, Nicolata R, Teixeira A, De Marco LA, Romano-Silva MA: Association study of the T102C 5-HT2A polymorphism in schizophrenia: Diagnosis, psychopathology ans suicidal behavior. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006, 141B (7): 802-802.

Ertugrul A, Kennedy JL, Masellis M, Basile VS, Jayathilake K, Meltzer HY: No association of the T102C polymorphism of the serotonin 2A receptor gene (HTR2A) with suicidality in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004, 69 (2–3): 301-305.

Correa H, De Marco L, Boson W, Nicolato R, Teixeira AL, Campo VR, Romano-Silva MA: Association study of T102C 5-HT(2A) polymorphism in schizophrenic patients: diagnosis, psychopathology, and suicidal behavior. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2007, 9 (1): 97-101.

Wrzosek M, Lukaszkiewicz J, Serafin P, Jakubczyk A, Klimkiewicz A, Matsumoto H, Brower KJ, Wojnar M: Association of polymorphisms in HTR2A, HTR1A and TPH2 genes with suicide attempts in alcohol dependence: a preliminary report. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 190 (1): 149-151. 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.04.027.

Khait VD, Huang YY, Zalsman G, Oquendo MA, Brent DA, Harkavy-Friedman JM, Mann JJ: Association of serotonin 5-HT2A receptor binding and the T102C polymorphism in depressed and healthy Caucasian subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005, 30 (1): 166-172. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300578.

Mann JJ: Neurobiology of suicidal behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003, 4 (10): 819-828.

Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A: Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979, 47 (2): 343-352.

Lahiri DK, Nurnberger JI: A rapid non-enzymatic method for the preparation of HMW DNA from blood for RFLP studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991, 19 (19): 5444-10.1093/nar/19.19.5444.

Swartz MK: The PRISMA statement: a guideline for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Pediatr Health Care. 2011, 25 (1): 1-2. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2010.09.006.

Tovilla-Zarate C, Camarena B, Apiquian R, Nicolini H: Association study and meta-analysis of the apolipoprotein gene and schizophrenia. Gac Med Mex. 2008, 144 (2): 79-83.

Kavvoura FK, Ioannidis JP: Methods for meta-analysis in genetic association studies: a review of their potential and pitfalls. Hum Genet. 2008, 123 (1): 1-14. 10.1007/s00439-007-0445-9.

Du L, Bakish D, Lapierre YD, Ravindran AV, Hrdina PD: Association of polymorphism of serotonin 2A receptor gene with suicidal ideation in major depressive disorder. Am J Med Genet. 2000, 96 (1): 56-60. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(20000207)96:1<56::AID-AJMG12>3.0.CO;2-L.

Vaquero-Lorenzo C, Baca-Garcia E, Diaz-Hernandez M, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Fernandez-Navarro P, Giner L, Carballo JJ, Saiz-Ruiz J, Fernandez-Piqueras J, Baldomero EB, et al: Association study of two polymorphisms of the serotonin-2A receptor gene and suicide attempts. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008, 147B (5): 645-649. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30642.

Bondy B, Kuznik J, Baghai T, Schule C, Zwanzger P, Minov C, de Jonge S, Rupprecht R, Meyer H, Engel RR, et al: Lack of association of serotonin-2A receptor gene polymorphism (T102C) with suicidal ideation and suicide. Am J Med Genet. 2000, 96 (6): 831-835. 10.1002/1096-8628(20001204)96:6<831::AID-AJMG27>3.0.CO;2-K.

Arias B, Gasto C, Catalan R, Gutierrez B, Pintor L, Fananas L: The 5-HT(2A) receptor gene 102T/C polymorphism is associated with suicidal behavior in depressed patients. Am J Med Genet. 2001, 105 (8): 801-804. 10.1002/ajmg.10099.

Tsai SJ, Hong CJ, Hsu CC, Cheng CY, Liao WY, Song HL, Lai HC: Serotonin-2A receptor polymorphism (102T/C) in mood disorders. Psychiatry Res. 1999, 87 (2–3): 233-237.

Crawford J, Sutherland GR, Goldney RD: No evidence for association of 5-HT2A receptor polymorphism with suicide. Am J Med Genet. 2000, 96 (6): 879-880. 10.1002/1096-8628(20001204)96:6<879::AID-AJMG39>3.0.CO;2-M.

Saiz PA, Garcia-Portilla MP, Paredes B, Arango C, Morales B, Alvarez V, Coto E, Bascaran MT, Bousono M, Bobes J: Association between the A-1438G polymorphism of the serotonin 2A receptor gene and nonimpulsive suicide attempts. Psychiatr Genet. 2008, 18 (5): 213-218. 10.1097/YPG.0b013e3283050ada.

Preuss UW, Koller G, Bahlmann M, Soyka M, Bondy B: No association between suicidal behavior and 5-HT2A-T102C polymorphism in alcohol dependents. Am J Med Genet. 2000, 96 (6): 877-878. 10.1002/1096-8628(20001204)96:6<877::AID-AJMG38>3.0.CO;2-V.

Zhang J, Shen Y, He G, Li X, Meng J, Guo S, Li H, Gu N, Feng G, He L: Lack of association between three serotonin genes and suicidal behavior in Chinese psychiatric patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008, 32 (2): 467-471. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.09.019.

Ono H, Shirakawa O, Nishiguchi N, Nishimura A, Nushida H, Ueno Y, Maeda K: Serotonin 2A receptor gene polymorphism is not associated with completed suicide. J Psychiatr Res. 2001, 35: 173-176. 10.1016/S0022-3956(01)00015-2.

Du L, Faludi G, Palkovits M, Demeter E, Bakish D, Lapierre YD, Sotonyi P, Hrdina PD: Frequency of long allele in serotonin transporter gene is increased in depressed suicide victims. Biol Psychiatry. 1999, 46 (2): 196-201. 10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00376-X.

Li D, Duan Y, He L: Association study of serotonin 2A receptor (5-HT2A) gene with schizophrenia and suicidal behavior using systematic meta-analysis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006, 340 (3): 1006-1015. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.101.

Paredes B, Alejandra SP, Paz G-PM, Morales B, Mercedes P, Fernandez I, Ivan G, Victoria A, Eliecer C, María B, et al: Asociación entre el polimorfismo A-1438G del gen del receptor de serotonina 2A (5HT2A) e impulsividad del comportamiento suicida. Emergencias. 2008, 20: 93-100.

Ono H, Shirakawa O, Nishiguchi N, Nishimura A, Nushida H, Ueno Y, Maeda K: Serotonin 2A receptor gene polymorphism is not associated with completed suicide. J Psychiatr Res. 2001, 35 (3): 173-176. 10.1016/S0022-3956(01)00015-2.

Abdolmaleky HM, Faraone SV, Glatt SJ, Tsuang MT: Meta-analysis of association between the T102C polymorphism of the 5HT2a receptor gene and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004, 67 (1): 53-62. 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00183-X.

Anguelova M, Benkelfat C, Turecki G: A systematic review of association studies investigating genes coding for serotonin receptors and the serotonin transporter: II. Suicidal behavior. Mol Psychiatry. 2003, 8 (7): 646-653. 10.1038/sj.mp.4001336.

Forero DA, Arboleda GH, Vasquez R, Arboleda H: Candidate genes involved in neural plasticity and the risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of 8 common variants. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2009, 34 (5): 361-366.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/13/25/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge our research volunteers who helped to recruit the participants in this study; we are also grateful to Andrea Torres who made all the genotype essays. The collection of data and the genotyping of subjects were carried out thanks to the support of grants from the UJAT-DAMC-2012-02 and CONACYT CB-2012-01-177459.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare not to have any competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

TZC and GCTB conceived the study, participated in its design, and helped to draft the manuscript. TZC, JRI, LNL and NH helped to perform the statistical analysis and to draft the manuscript. PGS and VSMP recruited participants and helped with data integration and analysis. GA, TZC and HN coordinated and supervised the integration of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

González-Castro, T.B., Tovilla-Zárate, C., Juárez-Rojop, I. et al. Association of the 5HTR2A gene with suicidal behavior: CASE-control study and updated meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 13, 25 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-25

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-25