Abstract

Background

For older adults, hospitalization frequently results in deterioration of mobility and function. Nevertheless, there are little data about how older adults exercise in the hospital and definitive studies are not yet available to determine what type of physical activity will prevent hospital related decline. Strengthening exercise may prevent deconditioning and Pilates exercise, which focuses on proper body mechanics and posture, may promote safety.

Methods

A hospital-based resistance exercise program, which incorporates principles of resistance training and Pilates exercise, was developed and administered to intervention subjects to determine whether acutely-ill older patients can perform resistance exercise while in the hospital. Exercises were designed to be reproducible and easily performed in bed. The primary outcome measures were adherence and participation.

Results

Thirty-nine ill patients, recently admitted to an acute care hospital, who were over age 70 [mean age of 82.0 (SD= 7.3)] and ambulatory prior to admission, were randomized to the resistance exercise group (19) or passive range of motion (ROM) group (20). For the resistance exercise group, participation was 71% (p = 0.004) and adherence was 63% (p = 0.020). Participation and adherence for ROM exercises was 96% and 95%, respectively.

Conclusion

Using a standardized and simple exercise regimen, selected, ill, older adults in the hospital are able to comply with resistance exercise. Further studies are needed to determine if resistance exercise can prevent or treat hospital-related deterioration in mobility and function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Many older adults develop functional decline and impaired walking while in the hospital. [1–6] Preventing and treating hospital-related deconditioning is, therefore, of great importance. Nevertheless, most hospital exercise protocols are untested and poorly described.

Although the exact cause of hospital-related deconditioning is uncertain and the optimal type and intensity of exercise needed to prevent deconditioning is yet to be determined, many studies show that loss of muscle mass and deteriorating muscle strength occurs after several days of bedrest.[7, 8] Moreover, many older adults have impaired muscle strength prior to admission to the hospital.[9] Given low baseline levels of muscle strength at the time of hospital admission, any further deterioration of strength due to bedrest may quickly cause dependency in walking and other functions. Accordingly, it appears logical to use an exercise program that specifically builds strength, such as high intensity resistance training (HIRT), to prevent hospital-related deconditioning. The crucial principle of this technique is to provide sufficient resistance to achieve muscle fatigue within 8 to 12 repetitions of an exercise.

Although the safety and efficacy of HIRT has been demonstrated with both nursing home residents and healthy older adults, [10–30] the ability to use HIRT in the acute care setting is unknown. Firstly, the acuity of illness might limit the use of resistance exercise. Secondly, it is uncertain whether hospitalized older adults can exercise at a level that would have a significant effect on muscle strength and function. Finally, many studies of HIRT use costly machines[12] that both determine the necessary resistance for each exercise and place the body in a mechanically effective position. This type of exercise equipment is not available in most hospitals, and it is unclear whether the integrity of a resistance exercise program can be maintained without it. Importantly, for frail older adults in hospital, any strengthening exercise program needs to provide enough resistance to train muscles while maintaining safe, correct posture and positioning.

We developed a set of resistance exercises that can be performed in hospital. The objectives of the exercise program are to: (1) allow the subject to exercise from bed, for ease of administration, (2) provide enough resistance so that muscle fatigue occurs before 10 repetitions, (3) strengthen the major muscle groups of the lower extremities, (4) utilize safe, effective procedures and postures, and (5) standardize and describe the exercise program so that it can be precisely reproduced. Our aim was to measure the adherence to and compliance with these exercises when performed in the setting of an acute care hospital.

Methods

Sample, setting, & study population

This randomized, controlled trial recruited subjects from geriatric, internal and family medicine wards at the Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, a tertiary care, university hospital, in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Patients received either resistance exercise or passive range of motion exercise (placebo). The Ethics Committee at the Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre approved the study protocol.

Consecutive subjects over age 70 were reviewed within one week of admission for potential inclusion. Subjects must have been walking prior to admission and able to follow the three-step command on the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).[31] We excluded patients with any of the following: requiring end-of-life care, needing more than 2 litres per minute of oxygen, the presence of a chest tube or central line, unstable or new onset angina, ventricular arrhythmia, diagnosed and symptomatic aortic stenosis, moderate to severe congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association class 3 or 4), blood pressure greater than 180/120 mmHg, acute musculoskeletal injury or inflammatory arthritis, hip or vertebral fracture in the past 6 months, severe chronic back or neck pain, kidney failure requiring dialysis, or severe fixed or progressive neurological disease, such as stroke with significant hemiplegia or advanced Parkinson's disease. Patients with an expected short length of stay were also excluded. Prior to enrolment, within one week of admission, the assessor reviewed each patient to determine eligibility. At the time of this assessment, if a patient's illness appeared to be resolving or if discharge was being planned, the subject was designated as a potential short stay subject and excluded. For suitable patients, the attending physician consented to study entrance. All subjects or their family members/guardians gave written consent for participation. Subjects were randomized in a 1:1 ratio in blocks of 8.

Exercise / Intervention

Both control and exercise groups received usual hospital care, including physiotherapy, if ordered. Subjects exercised 3 times per week, assisted by the physiotherapist, with a rest day between sessions. The resistance exercise program targeted the lower extremities, including the gluteal muscles, quadriceps, hamstrings, hip flexors, hip adductors/abductors, and plantar/dorsiflexors. Principles of postural alignment and correct exercise technique were stressed. Exhalation was coordinated with the exertion phase of the exercise. Each exercise was repeated 10 times, after which the subject could repeat the set to a maximum of three sets. Subjects exercised until discharge from the hospital unit, or for a maximum of 4 weeks. All exercise sessions were supervised by a physiotherapist.

Recognizing the importance of being able to accurately incorporate any therapeutic intervention into medical practice, we have detailed the exercise protocol in Table 1 and Figure 1. HIRT techniques were adapted so that exercise could be performed in bed and without the typical equipment used in many studies of HIRT, such as Cybex or Universal machines. The exercises incorporated principles of overload and specificity, consistent with the American College of Sports Medicine guidelines for strength training.[32] The resistance for single leg knee extension (Figure 1a), was based on the one-repetition maximum (1RM), calculated using 1 pound increments.[33] The 1RM is the maximum amount of weight an exerciser can lift while maintaining correct posture. Once exercising, single leg knee extension was performed using a weight equal to 60% to 80% of the 1RM. For the remaining strengthening exercises, resistance was achieved using weights, Therabands™ (rubber tubing) or springs, selecting a weight or length of tubing or spring that would achieve muscle fatigue within 10 repetitions. Exercises were progressed during the study. For each subject, the physiotherapist measured the length of Theraband™ required to cause muscle fatigue within 10 repetitions. If muscle fatigue failed to occur as the study proceeded, the theraband or spring length was shortened. Similarly, if the designated weight for the 1RM did not cause muscle fatigue within 10 repetitions, the amount of weight was increased.

Each strengthening exercise was taught using principles of the Pilates method.[34] The Pilates technique emphasizes proper positioning and uses breathing to facilitate relaxation. For example, many exercise programs attempt to strengthen the quadriceps muscle by extending the leg using a weight around the ankle with the exerciser seated upright in a chair. However, the length of the hamstring muscle usually limits this movement and, thus, to accomplish the exercise with this positioning, the exerciser must flex the lower back, creating a kyphotic posture and unnecessary pressure on the back. Instead, we exercise the quadriceps muscle in the supine position, with the legs supported by a half barrel, which allows the lumbar spine to rest in a neutral position (Figure 1a). In the neutral position, the anterior superior iliac spine and symphysis pubis are in the same horizontal plane. The lumbar spine is in its natural concave curve, thus minimizing the potential for adverse stress on the back during exercise. When extending the leg, the exerciser is taught to align the ankle, knee, and hip along the longitudinal axis, in order to prevent injury to the knee. Understanding proper exercise technique in this way enables the exerciser to strengthen muscle groups that are essential for postural control without developing unnecessary tension in other muscles or improper postural habits.

The control group performed six range of motion exercises for the lower limbs, using motions and repetitions similar to the resistance exercises, but carried out with passive motion produced by the physiotherapist.

Measures

The primary outcome measures were participation and adherence. Participation was defined as the total number of exercise sessions completed (at least 75% of one complete session performed) by a given subject, divided by the total number of possible sessions. Adherence was defined as the proportion of subjects with participation rates exceeding 75%. Other data collected at the time of admission included admission diagnosis, Folstein MMSE score, [31], and the 1RM for single leg knee extension.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables and between group comparisons were tested using Mann-Whitney U test and Fisher's Exact test (p < .05).

Results

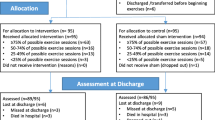

Three hundred and ninety-five consecutive subjects were reviewed within 5 days of hospital admission for enrollment eligibility. Of these, 107 (27%) were excluded because of expected short stay, 58 (15%) because of cardiac disease and 121 (31%) due to other medical conditions, of which the most common were cognitive impairment (25; 6%), infection (25; 6%) and back pain (24; 6%). Twenty-two subjects (6%) were excluded because they could not walk before hospitalization and inclusion of 35 subjects (9%) was declined by the attending physician. Thirteen subjects (3%) refused to participate. The remaining 39 subjects (10%) were randomly assigned to the resistance exercise or control group (Figure 2).

Subject Enrollment ROM, range of motion; PTA, prior to admission. aCardiac syndromes include unstable angina, congestive heart failure, or myocardial infarction. bInfection includes subjects with positive cultures for methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin resistant enterococci, clostridium difficile, or tuberculosis. cOther includes hemiparesis (stroke), hypertension, deaf, dialysis, DVT/PE, orthostatic hypotension, amputation, and severe nausea.

The baseline characteristics of the subjects in the exercise and control groups are presented in Table 2. The baseline measure of the 1RM for single leg knee extension was similar for both the control and exercise group (Table 2).

In the exercise group, participation was 71% and adherence was 63%. For the control group, participation and adherence were 96% and 95%, respectively (Table 3). Approximately 50% of the cohort had cognitive impairment, with a Folstein MMSE score of less than 24. Adherence and participation with exercise was not significantly different for those with cognitive impairment compared to those without cognitive impairment (Table 3).

The average weight used for the single leg knee extension exercise was 4.7 kg for the total group, 4.2 for women and 5.8 for men. The average duration for an exercise session was 10 minutes for the control group and 36.2 minutes for the exercise group (Table 3). Subjects were questioned about potential side effects after exercising. There were no adverse events or injuries related to participating in the study.

Discussion

For a select group of subjects without contraindications to exercise, resistance exercise can be successfully performed shortly after hospitalization. Participation and adherence rates in the intervention group were 71% and 63%, respectively. The exercise program was accomplished within 30–40 minutes, thrice weekly. The cost of the equipment (all Canadian dollars) was approximately $100 for the half-barrel, $50 for the spring, and $79 for the weight, which consisted of twenty 1 pound removable inserts.

Nevertheless, adherence and participation were significantly different in the resistance exercise group compared to the passive range of motion group, indicating that resistance exercise is difficult for some acutely-ill hospitalized patients. Differences in adherence and participation between groups is likely related to the increased intensity and difficulty of the resistance exercises compared to the passive ROM exercises. The longer length of time needed to complete the resistance exercise compared to the ROM exercise may also have influenced compliance.

The proportion of patients with contraindications to the exercise program was high, and 90% of elderly patients admitted to the hospital were either ineligible or non-participants. Still, the percentage of subjects included in this study was higher than in another hospital-based exercise intervention study,[35] where 98% of subjects did not participate. Notably, it appears that many non-participants were appropriately excluded, as they would not have benefited from an exercise program of short duration, such as those expected to have a brief hospital stay (27%), who were unable to walk prior to admission (6%), or were admitted for end-of-life care (3%). By contrast, concomitant review reveals that 73 patients (18%) could have feasibly exercised with changes to the protocol. For example, patients with bacteriological culture results necessitating isolation (e.g. methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) could have had their equipment isolated. Back pain, Parkinson's disease, low-grade hypertension, deafness, dialysis, and leg amputation might each be unnecessary restrictions. Finally, some of the reasons for physician non-consent to exercise (35 patients; 9% of subjects evaluated and 26% of those potentially eligible) may be amenable to education. Nonetheless, further investigation may be necessary to determine reasonable exclusion criteria to use when studying exercise in hospitalized patients, thus clarifying the feasibility of using these exercises in a broader geriatric population.

Another limitation of the study was the small sample size. Because of this, we were able to detect only a large effect size as significantly significant. This strikes us as a sensible strategy. If many patients are to be excluded, it is reasonable that most of those who are enrolled can participate. Even for this small number, however, we were interested to observe that those who participated exercised more vigorously than is common practice in most geriatric and medical units, where the predominant form of exercise can be walking or other low-intensity training. In contrast, in this study the average amount of weight for unilateral knee extension was 4.7 kg.

A possible placebo effect resulting from the subjects' knowledge they were participating in a study may have increased motivation to exercise, thereby positively influencing measures of adherence and compliance. However, the placebo effect would be minimized by the subjects' lack of knowledge about their group assignment. Although adherence and compliance were studied, the benefits of the exercise program were not determined. Particularly, the exercise program may not have a beneficial effect for subjects with a short length of stay in the hospital.

We found that people with mild to moderate cognitive impairment were able to comply with resistance exercise. This result is in accord with other studies,[11, 12, 26, 30] which establish that dementia, of mild to moderate severity, is not a major obstacle to performing resistance exercise.

To date, there are few studies that examine the role of exercise in the hospital. Siebens et al[33] investigated whether an exercise program could improve hospital outcomes for 300 medical and surgical patients, age 70 years and older using low intensity exercises (without weights) and walking. They chose a minimally challenging exercise program because of their concern about the potential risks of exercising older hospitalized patients more vigorously. The authors commented that the low intensity of the exercises may be one reason the program failed to demonstrate a significant benefit in hospital length of stay, health indicators, mobility measures, and most functional measures. Our study is the first of which we are aware in which systematic evaluation of resistance exercise in the acute care setting demonstrates that an important proportion of selected at-risk older adults are able to safely comply with resistance exercise.

Conclusion

Prescribing resistance exercise to targeted elderly, acutely ill, hospitalized patients results in acceptable compliance. Further research is needed to determine whether such exercise can prevent and treat the common and morbid problem of hospital related deconditioning. Future studies should compare resistance training to other exercise modalities, such as walking and low intensity exercise, using functional outcome measures and performance-based measures to determine efficacy.

References

Bonner CD: Rehabilitation instead of bedrest?. Geriatrics. 1969, 24: 109-118.

Warshaw GA, Moore JT, Friedman SW, Currie CT, Kennie DC, Kane WJ, Meaars PA: Functional disability in the hospitalized elderly. JAMA. 1982, 248: 847-850. 10.1001/jama.248.7.847.

McVey LJ, Becker PM, Saltz CC, Feussner JR, Cohen JH: Effect of a geriatric consultation team on functional status of elderly hospitalized patients. A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1989, 110: 79-84.

Hirsch CH, Sommers L, Olsen A, Mullen L, Winograd CH: The natural history of functional morbidity in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990, 38: 1296-1303.

Mahoney JE, Sager MA, Jalaluddin M: New walking dependence associated with hospitalization for acute medical illness: Incidence and significance. J Gerontol: Med Sci. 1998, 53A: M307-312.

Sager MA, Franke T, Inouye SK, Landefeld CS, Morgan TM, Rudberg MA, Sebens H, Winograd CH: Functional outcomes of acute medical illness and hospitalization in older persons. Arch Intern Med. 1996, 156: 645-652. 10.1001/archinte.156.6.645.

Appell HJ: Muscular atrophy following immobilisation. A review. Sports Med. 1990, 10 (1): 42-58.

Booth FW: Physiologic and biochemical effects of immobilization on muscle. Clin Orthop. 1987, 219: 15-20.

Hagerman FC, Walsh SJ, Staron RS, Hikida RS, Gilders RM, Murray TF, Toma K, Ragg KE: Effects of high-intensity resistance training on untrained older men. I. Strength, cardiovascular, and metabolic responses. J Gerontol Biol Sci. 2000, 55: B336-346.

Hopp JF: Effects of age and resistance training on skeletal muscle: A review. Phys Ther. 1993, 73: 361-373.

Fiatarone MA, Marks EC, Ryan ND, Meredith CN, Lipsitz LA, Evans WJ: High-intensity strength training in nonagenarians. Effects on skeletal muscle. JAMA. 1990, 263: 3029-3034. 10.1001/jama.263.22.3029.

Fiatarone MA, O'Neill EF, Ryan ND, Clements KM, Solares GR, Nelson ME, Roberts SB, Kehayias JJ, Lipsitz LA, Evans WJ: Exercise training and nutritional supplementation for physical frailty in very elderly people. N Engl J Med. 1994, 330: 1769-1775. 10.1056/NEJM199406233302501.

Chandler JM, Hadley EC: Exercise to improve physiologic and functional performance in old age. Clin Geriatr Med. 1996, 12: 761-784.

Hunter GR, Treuth MS, Weinsier RL, Ketes-Szabo T, Kell SH, Nicholson C: The effects of strength conditioning on older women's ability to perform daily tasks. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995, 43: 756-760.

Adams KJ, Swank AM, Berning JM, Stevene-Adams PG, Barnard KL, Shimp-Bowerman J: Progressive strength training in sedentary, older African American women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001, 33: 1567-1576. 10.1097/00005768-200109000-00021.

Hakkinen K, Pakarinen A, Kraemer WJ, Hakkinen A, Valkeinen H, Alen M: Selective muscle hypertrophy, changes in EMG and force, and serum hormones during strength training in older women. J Appl Physiol. 2001, 91: 569-580.

Schlicht J, Camaione DN, Owen SV: Effect of intense strength training on standing balance, walking speed, and sit-to-stand performance in older adults. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2001, 56: M281-286.

Cress ME, Buchner DM, Questad KA, Esselman PC, deLateur BJ, Schwartz RS: Exercise: effects on physical functional performance in independent older adults. J Gerontol Med Sci. 1999, 54: M242-248.

Tracy BL, Ivey FM, Hurlbut D, Martel GF, Lemmer JT, Siegel EL, Metter EJ, Fozard JL, Fleg JL, Hurley BF: Muscle quality. II. Effects of strength training in 65- to 75-yr-old men and women. J Appl Physiol. 1999, 86: 195-201.

Tsutsumi T, Don BM, Zaichkowsky LD, Delizonna LL: Physical fitness and psychological benefits of strength training in community dwelling older adults. Appl Human Sci. 1997, 16: 257-266.

Welsh L, Rutherford OM: Effects of isometric strength training on quadriceps muscle properties in over 55 year olds. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1996, 72: 219-223.

Sipila S, Suominen H: Effects of strength and endurance training on thigh and leg muscle mass and composition in elderly women. J Appl Physiol. 1995, 78: 334-340.

Ades PA, Ballor DL, Ashikaga T, Utton JL, Nair KS: Weight training improves walking endurance in healthy elderly persons. Ann Intern Med. 1996, 124: 568-572.

Buchner DM, Cress ME, de Lateur BJ, Esselman PC, Margherita AJ, Price R, Wagner EH: The effect of strength and endurance training on gait, balance, fall risk, and health services use in community-living older adults. J Gerontol Med Sci. 1997, 52: M218-224.

Charette SL, McEvoy L, Pyka G, Snow-Harter C, Guido D, Wiswell RA, Marcus R: Muscle hypertrophy response to resistance training in older women. J Appl Physiol. 1991, 70: 1912-1916.

Fisher NM, Pendergast DR, Calkins E: Muscle rehabilitation in impaired elderly nursing home residents. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991, 72: 181-185.

Frontera WR, Meredith CN, O'Reilly KP, Knuttgen HG, Evans WJ: Strength conditioning in older men: skeletal muscle hypertrophy and improved function. J Appl Physiol. 1988, 64: 1038-1044.

Frontera WR, Meredith CN, O'Reilly KP, Evans WJ: Strength training and determinants of VO2max in older men. J Appl Physiol. 1990, 68: 329-333.

Judge JO, Whipple RH, Wolfson LI: Effects of resistive and balance exercises on isokinetic strength in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994, 42: 937-946.

Sauvage LR Jr, Myklebust BM, Crow-Pan J, Novak S, Millington P, Hoffman MD, Hartz AJ, Rudman D: A clinical trial of strengthening and aerobic exercise to improve gait and balance in elderly male nursing home residents. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1992, 71: 333-342.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975, 12: 189-198. 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6.

Pollock ML, Gaesser GA, Butcher JD: American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. The recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, and flexibility in health adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998, 30: 975-991. 10.1097/00005768-199806000-00032.

Nichols JF, Omizo DK, Peterson KK, Nelson KP: Efficacy of heavy resistance training for active women over sixty: muscular strength, body composition, and program adherence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993, 41: 205-210.

Menezes Allan: The Complete Guide to Joseph H. Pilates' Techniques of Physical Conditioning. Hunter House. 1990

Siebens H, Aronow H, Edwards D, Ghasemi Z: A randomized controlled trial of exercise to improve outcomes of acute hospitalization in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000, 48: 1545-1552.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2318/3/3/prepub

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Heather Merry, MSc, for statistical expertise and Kim Kraushar, a kinesiologist and Pilates teacher, for help with exercise design. This work was funded by the Queen Elizabeth II Hospital Research Fund and the Dalhousie University Internal Medicine Research Fund. Drs. MacKnight and Rockwood are supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Rockwood is also supported by the Kathryn Allen Weldon Chair in Alzheimer Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing Interests

Dr. Laurie Mallery produced an exercise video and manual that demonstrate how to perform Pilates based resistance exercise.

Authors' Contributions

LM conceived of the idea for the study. LM, EAM, CLK and EME designed the study. EAM and LM drafted the manuscript and CLK, EME, KR and CM contributed to critical revision of the manuscript. LM, CLK, EME, KR, and CM participated in the analysis of data.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Mallery, L.H., MacDonald, E.A., Hubley-Kozey, C.L. et al. The Feasibility of performing resistance exercise with acutely ill hospitalized older adults. BMC Geriatr 3, 3 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-3-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-3-3