Abstract

Background

The Tephritidae family of insects includes the most important agricultural pests of fruits and vegetables, belonging mainly to four genera (Bactrocera, Ceratitis, Anastrepha and Rhagoletis). The olive fruit fly, Bactrocera oleae, is the major pest of the olive fruit. Currently, its control is based on chemical insecticides. Environmentally friendlier methods have been attempted in the past (Sterile Insect Technique), albeit with limited success. This was mainly attributed to the lack of knowledge on the insect's behaviour, ecology and genetic structure of natural populations. The development of molecular markers could facilitate the access in the genome and contribute to the solution of the aforementioned problems. We chose to focus on microsatellite markers due to their abundance in the genome, high degree of polymorphism and easiness of isolation.

Results

Fifty-eight microsatellite-containing clones were isolated from the olive fly, Bactrocera oleae, bearing a total of sixty-two discrete microsatellite motifs. Forty-two primer pairs were designed on the unique sequences flanking the microsatellite motif and thirty-one of them amplified a PCR product of the expected size. The level of polymorphism was evaluated against wild and laboratory flies and the majority of the markers (93.5%) proved highly polymorphic. Thirteen of them presented a unique position on the olive fly polytene chromosomes by in situ hybridization, which can serve as anchors to correlate future genetic and cytological maps of the species, as well as entry points to the genome. Cross-species amplification of these markers to eleven Tephritidae species and sequencing of thirty-one of the amplified products revealed a varying degree of conservation that declines outside the Bactrocera genus.

Conclusion

Microsatellite markers are very powerful tools for genetic and population analyses, particularly in species deprived of any other means of genetic analysis. The presented set of microsatellite markers possesses all features that would render them useful in such analyses. This could also prove helpful for species where SIT is a desired outcome, since the development of effective SIT can be aided by detailed knowledge at the genetic and molecular level. Furthermore, their presented efficacy in several other species of the Tephritidae family not only makes them useful for their analysis but also provides tools for phylogenetic comparisons among them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Tephritidae family of insects includes the most important agricultural pests of fruits and vegetables. Most of them belong to four genera: Bactrocera, Ceratitis, Anastrepha and Rhagoletis. Ceratitis includes 89 different species. Among them, the Medfly, Ceratitis capitata, is the best so far studied member of the family and attacks over 350 different fruits and vegetables in tropical and sub-tropical regions [1], causing damages of hundreds of billions $ per year. Anastrepha is the most economically important genus of pests in the American tropics and subtropics and includes more than fifteen economically important pests [2]. Rhagoletis includes more than 60 described species distributed in Eurasia and the New World, several of which are important pests [3]. Bactrocera is among the largest genera in Tephritidae including about 500 species [4, 5]. Many of them are serious pests of fruits and vegetables in different parts of the world [2]. The only member of this genus present in Europe is the olive fruit fly, Bactrocera oleae, the major pest of the olive fruit, with estimated damages of 5–30% of the global olive production, resulting in economic losses of about 800 million $ per year [6, 7]. Quarantine orders against non-indigenous Tephritidae exist in all countries, demonstrating the appreciation of these species' destructive abilities and invasiveness success [8–12].

Currently, control of these insects is based on chemical insecticides. The Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) is the most promising, environmentally friendly method, based on the mass production and release of sterile insects into field populations. When the released males mate with the field females no progeny are produced and the field population may finally be suppressed. The appreciation of the negative effect of the released females [13] lead to the development of genetic sexing strains (GSS) [14]. Successful development of such approaches, however, presupposes an understanding of the species at the genetic, molecular and population level. Additionally, new molecular and genetic tools, such as genetic transformation, could prove very helpful since they can improve mass rearing of effective male insects. Such knowledge developed in the Medfly lead to successful SIT protocols (for a review, see [15]), whereas respective lack in the olive fly lead to fruitless attempts. In the early '70s, efforts to employ the SIT against the olive fly were unsuccessful [16], principally due to the low competitiveness of the sterile mass-reared males compared to the wild ones [17]. Several molecular and genetic studies have changed B. oleae's research landscape in recent years. Among them we mention studies on population genetics [18–20], cytogenetics (for a review see [21]), sex-determining cascades [22, 23] and, most notably, the successful genetic transformation [24], an achievement that gives new perspectives towards the efficient use of the SIT.

Microsatellites constitute very powerful genetic and molecular markers [25–27]. In the Medfly they have been used to identify sources of origin, invasion phenomena, to design control strategies [28–31], as well as in the genetic mapping of the species [32]. This last possibility renders microsatellite markers particularly useful in the olive fly, since several years of efforts have provided no morphological markers and therefore the development of classical genetics has been entirely hindered (Mavragani, unpublished; Zacharopoulou, unpublished). In addition, such markers can also be helpful in SIT development. For example, they have been successfully used in the analysis of mating systems in B. dorsalis [33] and C. capitata [34, 35] and they can be used to detect the degree of differentiation between laboratory and wild flies, the main reason of SIT failure in the olive fly.

The present study enriches a previously described set of 15 microsatellite markers [36, 19] with 16 new ones. Most of these markers were proven polymorphic, some of them were localized in the polytene chromosomes of the species and many of them were successfully cross-amplified in other Tephritidae species. Their utility in genetic studies and evolutionary comparisons is considered.

Results and discussion

Isolation and characterization of microsatellites from small-insert genomic libraries and enriched libraries

Thirty-four microsatellite containing clones were isolated from small-insert genomic libraries and 24 from enriched libraries, yielding a total of 36 and 26 discrete microsatellite motifs, respectively, since a few of them contained more than one microsatellite motif (Table 1). Despite the use of an equal mix of (GT)15 and (CT)15 as probes, there was a clear predominance of GT over CT repeats obtained from the small-insert library. This most likely reflects a difference in the abundance of these sequences in the genome, as has been the case in other Diptera, such as D. melanogaster [37–39], D. simulans [40], A. gambiae [41] and C. capitata (Stratikopoulos et al., submitted) [28]. In hymenoptera, CT repeats seem to be more abundant than GT repeats, as studies in Apis mellifera and Bombus terrestris reveal [42].

A significant predominance of interrupted (60.5%) over perfect motifs (34.2%) was observed in both isolation approaches, while only a few (5.2%) were compound. These percentages are quite similar to those observed in C. capitata [28] and B. terrestris [42]. On the other hand, they are not in agreement with results from B. tryoni [43], B. morii [44], D. pseudoobscura [45] and a recent study in C. capitata (Stratikopoulos et al., submitted). Therefore, it is unclear whether these results represent the actual structure of microsatellites in the olive fly genome, since data from closely related species are conflicting. Possibly these results can be attributed to differences in isolation strategies.

In situ hybridization to polytene chromosomes

Cytological analysis of B. oleae has revealed five chromosomes (10 polytene arms) and a heterochromatic mass, corresponding to the five autosomes and the sex chromosomes, respectively (for a review see [21]). Well-defined polytene maps have been produced, providing the opportunity for a cytologic localization of molecular markers on the chromosomes.

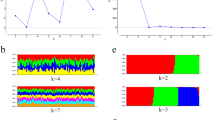

Twenty of the isolated microsatellite clones were in situ hybridised to the salivary gland polytene chromosomes of B. oleae, in order to identify their chromosomal localization. At hybridisation temperature of 58°C, sixteen of the microsatellite probes gave specific signals (Table 1) and 13 of them mapped to unique chromosome loci. Clone Boms20 hybridised to two neighbouring bands of the same chromosome region, Boms31 hybridised to two regions on the same chromosome arm, while Boms25 mapped to three regions on two chromosome arms (Table 1, Fig. 1) [Note that microsatellite loci and clones' names are written in italics whereas microsatellite markers' names are written in regular font]. These microsatellite clones gave the same multiple hybridisation pattern even at the higher hybridisation temperature of 62°C. Chromosome localization was not possible for four of the microsatellite probes, although tested at several hybridisation temperatures. Lack of hybridization signal can be attributed either to insufficient hybridization due to small probe length or to the fact that these clones may lie in heterochromatic regions (such as sex chromosomes or centromeric regions). Boms33 gave no detectable signal, while the remaining three gave multiple signals.

Schematic representation of the in situ localization of microsatellite markers on the polytene chromosomes of Bactrocera oleae. Arrows that originate from numbers in bold stand for the Boms microsatellite markers. Underlined numbers refer to microsatellite markers that give multiple signals. All other arrows refer to previously mapped loci [Zambetaki et al 1999].

The thirteen microsatellites that uniquely mapped to the polytene chromosomes of B. oleae are dispersed on seven polytene arms, establishing genetic markers for all five autosomes. Table 1 summarizes the microsatellite hybridization sites and Figure 1 schematically presents the relative positions of the hybridization signals to the polytene chromosome arms of B. oleae together with previously described markers [21]. Hybridization signals are presented in Figure 2.

Although their number is small, they enrich the already existing cytological map and are the basis for a low-resolution cytogenetic map that will facilitate future genome projects of the species. It is encouraging that these thirteen markers are dispersed in seven of the ten chromosome arms (except IR, IIIL, VL). However, our in situ hybridization data are still limited to support a claim of a uniform distribution of microsatellite loci in the olive fly genome.

Development of microsatellite markers

Unique sequences flanking each repeat array were used to design PCR primer pairs for the amplification of 42 microsatellites. Thirty-one primer pairs amplified a product of the expected size, as revealed by agarose gel electrophoresis (Table 2). Subsequently, all primer pairs that amplified a specific band were used for the genotyping of 20 individual wild flies (from Greece and Cyprus) and/or up to 37 individuals of a laboratory strain. In addition, 19 C. capitata microsatellite markers (Stratikopoulos et al., submitted) that cross-amplified in the olive fly were used, raising the total number of functional primer pairs to 50 (Table 2). In total, 37 primer pairs (29 designed for the olive fly and eight for the medfly) amplified a polymorphic and easily scorable PCR product, while eight pairs amplified a monomorphic one. The five remaining primer pairs generated PCR products that were not easily scored (shuttered or multiple bands or faint signal).

The mean allele number per locus was 4.63 for natural populations and 3.14 for laboratory strains (monomorphic loci excluded), demonstrating their usefulness in population analyses of the species. Conformation to HWE was tested for 26 loci for natural populations and 19 loci for laboratory strains, according to G2 criterion, at a significance level of 5%. Only five deviations were observed due to homozygosity excess, which can be attributed to small sample size or to the presence of null alleles (Table 2).

Cross – species amplification in Tephritidae

The 29 primer pairs designed for the olive fly and proved polymorphic were tested in a pooled mix of five flies from each one of 11 Tephritidae species. Twenty-six of them amplified a specific DNA fragment, at least in one of the species examined. Four species belong to Bactrocera (B. correcta, B. cucurbitae, B. dorsalis and B. tryoni), four to Anastrepha (A. fraterculus, A. ludens, A. serpetina and A. striata), two to Ceratitis (C. capitata and C. fasciventris) and one belongs to Rhagoletis (R. cerasi) (Tables 3 and 4).

A total of 113 PCR products were amplified. The species with the highest degree of amplification was B. tryoni (19/29), while with the lowest was Rhagoletis cerasi (8/29). As expected, the highest percentage of amplification was inside Bactrocera, with a mean of 49.1%. Ceratitis presented the next higher amplification degree (34.5%), followed by Rhagoletis and Anastrepha (27.6% and 24.1%, respectively) (Table 4 and Figure 3-1). It is worth mentioning that B. cucurbitae exhibited very low amplification rate, similar to that of Anastrepha. Finally, C. capitata presented substantially lower degree of amplification than C. fasciventris.

The majority of PCR products had similar size (less than ~50 bp difference, as estimated by agarose gel electrophoresis) with those obtained in B. oleae (about 76%). Still, the highest degree of PCR product size conservation was inside Bactrocera (84.2%), although Ceratitis showed a comparable percentage (80%). Anastrepha and Rhagoletis presented significantly lower values (64.3% and 50%, respectively) (Table 4 and Figure 3-2). Surprisingly, B. cucurbitae showed very low size conservation (66.7%), comparable to that of Anastrepha, implying that the low amplification value mentioned before may not be a PCR artefact. This in not the case in C. capitata, since size conservation is very high (87.5%). This value is higher than that of C. fasciventris and comparable to that of Bactrocera, suggesting that medfly's low amplification value is more likely a PCR artefact.

Analysis of cross-species amplification products

Amplification of a band of expected size does not necessarily mean that the expected microsatellite motif is also present. To evaluate the degree of motif conservation, 31 of the reactions that produced a specific band were subcloned and sequenced. We focused on PCR products of similar to the expected size and distributed in as many species as possible. Twenty-seven of the amplification products harboured a repeat motif, 25 of which contained the same as that of B. oleae. Six of the products harboured new motifs (instead of or in addition to the expected ones) (Table 5).

Nineteen (of the 31) sequencing reactions were performed in Bactrocera. The presence of a microsatellite motif in 18 of them (16 of which had the expected motif), demonstrates their potential in the analysis of other Bactrocera species. Results from other genera are encouraging, although preliminary. In Ceratitis, for example, four sequencing reactions were performed, three of which exhibited the expected motif. In Anastrepha, five sequencing reactions were performed, all of which exhibited a microsatellite motif with four cases possessing the expected one (however, they all refer to the same locus in four different species). Finally, in Rhagoletis, three sequencing reactions were performed, one of which exhibited a microsatellite repeat of the expected motif. These results are summarized in Tables 4 and 5 and demonstrate the potential utility of these markers in the analysis of Tephritidae genera other than Bactrocera.

Mean number of uninterrupted repeats was measured only in cases where the expected motif was present in cross-species amplification products (Table 4). In seventeen cases within Bactrocera (regarding seven microsatellite loci), the mean number of uninterrupted repeats was 9.8 for B. oleae and 5.4 for the other Bactrocera species. Same analysis for three PCR products (regarding three microsatellites) in Ceratitis gave a mean of 9.0 and 5.0 uninterrupted repeats for B. oleae and Ceratitis, respectively. Although sequencing data are still limited, it is obvious that microsatellites tend to present longer arrays in the species in which they were isolated from. This has been described in a variety of species, such as Drosophila [40, 46] and primates [47], and has been attributed to the fact that microsatellites can evolve directionally and at different rates in closely related species.

Sequencing analysis and phylogenetic comparisons

Although we did not perform a phylogenetic analysis, it seems that measures of cross-species amplification (e.g., percentages of functional primers and expected size of PCR products) are indicative of the phylogenetic history of these species. Our results support the notion that three of the Bactrocera species are very close to B. oleae, while the fourth (B. cucurbitae) seems to be more distant (Table 4, Figure 3). Also, Ceratitis seems to be more closely related to Bactrocera than Anastrepha and Rhagoletis seems to be the most distantly related genus to Bactrocera. These results perfectly replicate the exact same relationships observed in the most recent phylogenetic analysis of these species based on mtDNA sequencing data [48]. Secondarily, they are also supported by several other studies from different insect species based on alignment of mitochondrial 16S rDNA sequences [49, 50] and 18S rDNA sequences [51], which show that Bactrocera is more closely related to Ceratitis, and closer to Anastrepha than it is to Rhagoletis. In addition, we also performed sequencing alignments of a few cross-species amplification products of some of our markers (data not shown). In all cases, the different species were clustered to their respective genera with high bootstrap values. Although these data are very limited, they come from dispersed regions of nuclear DNA which gives significant value to phylogenetic analyses. There are studies supporting that microsatellite data can shed light to phylogenetic relationships among closely related taxa [52–54]. Sequencing analysis of more microsatellite markers can probably reveal complex phylogenetic relationships among different Tephritidae species, especially in cases of species complexes.

Polymorphism of cross-species microsatellite markers

Presence of a microsatellite motif does not necessarily mean that these loci can be used as genetic markers. Nineteen microsatellite markers developed in the medfly cross-amplified in the olive fly (Table 2). The fact that eight of them were polymorphic in a relative small sample (twenty wild flies) confirms the possible utility of the markers presented here in the analysis of other Tephritidae species.

Conclusion

Since their discovery, microsatellite markers have been particularly useful in population and genetic analyses, mainly due to their high degree of polymorphism. Their significance is even greater in organisms like the olive fly, where the lack of morphological markers makes classical genetic analysis practically impossible. The interest in olive fly's genetics is not only theoretical, since modern genetic and molecular tools have benefited several operational SIT programmes, particularly those where GSSs are involved [15]. The observed polymorphism of the developed microsatellite markers (both in laboratory and natural populations) guarantees their utility in genetic and population analyses. A subset of these markers has already been successfully used in previous population studies [36, 19]. The existence of well-described polytene chromosomes in the olive fly [21] and the possibility of cytological localization of molecular markers by in situ hybridisation provide a powerful method to link the genetic and molecular information of an organism. The existence of defined polytene chromosomes in other Diptera [55, 56] also offers the opportunity to establish syntenic linkages and to study the evolutionary relationships of separate chromosomal segments [57, 21]. Cross-species amplification of the developed markers to other Tephritidae demonstrates their potential utility in those species. Sequencing analysis of several cross-amplified products revealed a varying degree of conservation that declines outside the Bactrocera genus. Such sequencing analyses can also assist the clarification of phylogenetic relationships among different species, particularly in cases of species complexes.

Methods

Fly culture and stocks

Field-collected samples: Olive fruits were collected and kept in the laboratory until adult flies emerged. These flies were preserved individually at -20°C until DNA extraction.

Laboratory strain

B. oleae flies used for in situ hybridisation and polymorphism analysis were obtained from the Department of Biology, "Demokritos" Nuclear Research Center, Athens, Greece. In our laboratory the stock was reared on an artificial medium based on yeast hydrolysate, sucrose, egg yolk and water [58–60] at 25 ± 1°C and a 12 h light: 12 h dark cycle.

Construction and screening of total small insert genomic libraries

Genomic DNA was extracted from adult flies of the laboratory strain as described in [61]. Approximately 3 μg of genomic DNA were digested to completion with Mbo I and digestion products were electrophoresed in 1% agarose gel (Seakem GTG). Restriction fragments that ranged between 500 bp and 1200 bp were isolated from the gel (Jetquick gel extraction kit, Genomed) and cloned into the BamHI site of plasmid vector pBlueskript II SK (Stratagene). About 104 recombinant clones were transferred onto nylon membranes (Hybond-N, Amersham), screened with a mix of radioactively labeled (CT)15 and (GT)15 oligonucleotides. Labelling was performed with terminal transferase (Promega), under the conditions suggested by the manufacturer. Hybridisation was performed at 48°C in standard hybridisation solution (6× SSC, 0.5% SDS, 5× Denhardt's) for at least 16 hours. Membranes were then washed twice for 5 min in 2× SSC/0.1% SDS at 25°C and once for 15 min in 1× SSC/0.1% SDS at 37°C and subsequently exposed with film. Positive colonies underwent a secondary screening and plasmid DNA was then purified by the alkaline lysis method [62] and electrophoresed. Clones of convenient size inserts (i.e., 500–1000 bp) were sequenced (Thermo Sequenase core Sequencing kit, Amersham). Sequencing reactions were analysed in an automatic sequenator and the microsatellite repeat motif was determined.

Construction of microsatellite-enriched genomic libraries

Genomic DNA was extracted as above. Enriched libraries were prepared according to [63]. Seven libraries were constructed using different oligonucleotide probes [(GA)15, (CA)15, (GT)15, (CT)15, (AT)15, (GC)15 and (GAC)10]. Two rounds of enrichment were performed for each library. Enriched products were cloned either in plasmid vector pBlueskript SKII digested with EcoRI, (without removal of the amplification linkers), or into the BamHI site of the pUC18 vector (Ready-To-Go™ pUC18/BamHI, Amersham), (after linker removal). Insert size of recombinant clones was estimated on agarose gels and selected clones were sequenced as above. Selection was done either at random, or after Southern transfer and hybridization with (GT)15 and (CT)15 radiolabelled probes.

In situ hybridization procedures

Squash preparations of salivary gland chromosomes were made from 10–12 day-old third instar larvae and 1–2 day old pupae, as previously described [64]. Microsatellite containing clones were labelled with digoxigenated dUTP (Dig-11dUTP) using the random priming method and in situ hybridized to polytene chromosomes according to [64]. Hybridization temperature was 55–62°C (Table 1). Signals were detected with specific antibodies (ROCHE Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Five or more chromosomal preparations were hybridized with each probe and at least ten well-spread polytene nuclei per preparation were examined to identify the hybridization signals.

Genotyping

PCR amplification was performed in a 10 μl volume that contained ~10 ng of DNA, 1.6 mM MgCl2, 1× reaction buffer [Promega: 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), 50 mM KCl, 0.1% Triton X-100], 0.2 U Taq polymerase (Promega), 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 3 pmol of each primer. PCR products were subsequently separated in 1.5% agarose gels. For genotyping, PCRs were performed as above with the only difference that one fifth of one of the primers of each pair was end-labeled with [γ32P]-ATP, using T4 polynucleotide kinase (MBI, Fermentas) [65]. Amplification was performed on a PTC-100 thermocycler (MJ Research Inc) for 30 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 50°C and 1 min at 72°C. PCR products were electrophoresed on 5% denaturing polyacrylamide gels and visualized by autoradiography.

Data analysis

Genetic variability was measured as the mean number of alleles per locus, effective number of alleles and observed and expected heterozygosity. Conformation to HWE was tested at a significance level of 5%, according to G2 criterion. All computations were performed with POPGENE version 1.31 software [66].

Sequencing of cross-species amplification products

PCR products were electrophoresed, isolated from gel with the 'PCR Clean up and Gel extraction' kit (Nucleospin) and subsequently ligated to the pCR2.1-TOPO vector with the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). Recombinant vectors were used to transform E. coli competent cells of the XL-1 strain. Plasmid DNA was extracted with the alkaline lysis method, as above and sequence analysis was performed by Macrogen Inc (Korea).

References

Fletcher BS: Life history strategies of tephritid fruit flies. Fruit flies, their biology, natural enemies and control. Edited by: Robinson AS, Hooper G. 1989, Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers, 3B: 195-208.

White IM, Elson-Harris MM: Fruit Flies of Economic Significance: Their Identification and Bionomics. 1994, CAB International & ACIAR, Wallingford

Smith JJ, Bush GL: Phylogeny of the genus Rhagoletis (diptera: tephritidae) inferred from DNA sequences of mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase II. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 1997, 7 (1): 33-43. 10.1006/mpev.1996.0374.

Drew RAI: The tropical fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae: Dacinae) of the Australasian and Oceanian regions. 1989, Memoirs – Queensland Museum, 26-

Drew RAI, Hancock DL: Phylogeny of the tribe Dacini (Dacinae) based on morphological, distributional, and biological data. Fruit Flies (Tephritidae): Phylogeny and Evolution of Behavior. Edited by: Aluja M, Norrbom AL. 2000, Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 491-504.

Mazomenos BE:Dacus oleae. World crop pests. Edited by: Robinson AS, Hooper G. 1989, Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam, 3B: 169-177.

Montiel-Bueno A, Jones O: Alternative methods for controlling the olive fly, Bactrocera oleae, involving semio-chemicals. IOBC Wprs Bull. 2002, 25: 1-11.

Aketarawong N, Bonizzoni M, Thanaphum S, Gomulski LM, Gasperi G, Malacrida AR, Gugliemino CR: Inferences on the population structure and colonization process of the invasive oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel). Molecular Ecology. 2007, 16 (17): 3522-3532. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03409.x.

Baliraine FN, Bonizzoni M, Guglielmino CR, Osir EO, Lux SA, Mulaa FJ, Gomulski LM, Zheng L, Quilici S, Gasperi G, Malacrida AR: Population genetics of the potentially invasive African fruit fly species, Ceratitis rosa and Ceratitis fasciventris (Diptera: Tephritidae). Molecular Ecology. 2004, 13 (3): 683-695. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2004.02105.x.

Duyck P, David P, Junod G, Brunel C, Dupont R, Quilici S: Importance of competition mechanisms in successive invasions by polyphagous tephritids in La Réunion. Ecology. 2006, 87 (7): 1770-1780. 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[1770:IOCMIS]2.0.CO;2.

Malacrida AR, Gomulski LM, Bonizzoni M, Bertin S, Gasperi G, Guglielmino CR: Globalization and fruitfly invasion and expansion: The medfly paradigm. Genetica. 2007, 131 (1): 1-9. 10.1007/s10709-006-9117-2.

Thomas DB: Hot peppers as a host for the Mexican fruit fly Anastrepha ludens (Diptera: Tephritidae). Florida Entomologist. 2004, 87 (4): 603-608. 10.1653/0015-4040(2004)087[0603:HPAAHF]2.0.CO;2.

Andrewartha HG, Birch LC: Some recent contributions to the study of the distribution and abundance of insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 1960, 5: 219-242. 10.1146/annurev.en.05.010160.001251.

Whitten MJ: Automated sexing of pupae and its usefulness in control by sterile insects. J Econ Entomol. 1969, 62: 272-273.

Robinson AS: Genetic sexing strains in Medfly, Ceratitis capitata, Sterile Insect Technique Programmes. Genetica. 2002, 116: 5-13. 10.1023/A:1020951407069.

Economopoulos AP, Avtzis N, Zervas G, Tsitsipis J, Haniotakis G, Tsiropoulos G, Manoukas A: Experiments on control of olive fly, Dacus oleae (Gmelin), by combined effect of insecticides and releases of gamma-ray sterilized insects. Journal of Applied Entomology. 1977, 83: 201-215.

Economopoulos AP, Zervas GA: Sterile insect technique and radiation in insect control. IAEA-SM-255/39. 1982, 357-368.

Zouros E, Loukas M: Biochemical and colonization genetics of Dacus oleae (Gmelin). Fruit flies, their biology, natural enemies and control. Edited by: Robinson AS, Hooper G. 1989, Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers, 3B: 75-87.

Augustinos AA, Mamuris Z, Stratikopoulos E, D'Amelio S, Zacharopoulou A, Mathiopoulos KD: Microsatellite analysis of olive fly populations in the mediterranean indicates a westward expansion of the species. Genetica. 2005, 125 (2–3): 231-241. 10.1007/s10709-005-8692-y.

Nardi F, Carapelli A, Dallai R, Roderick GK, Frati F: Population structure and colonization history of the olive fly, Bactrocera oleae (Diptera, Tephritidae). Molecular Ecology. 2005, 14 (9): 2729-2738. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02610.x.

Mavragani-Tsipidou P: Genetic and cytogenetic analysis of the olive fruit fly Bactrocera oleae (Diptera: Tephritidae). Genetica. 2002, 116 (1): 45-57. 10.1023/A:1020907624816.

Lagos D, Koukidou M, Savakis C, Komitopoulou K: The transformer gene in Bactrocera oleae: The genetic switch that determines its sex fate. Insect Molecular Biology. 2007, 16 (2): 221-230. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00717.x.

Lagos D, Ruiz MF, Saìnchez L, Komitopoulou K: Isolation and characterization of the Bactrocera oleae genes orthologous to the sex determining Sex-lethal and doublesex genes of Drosophila melanogaster. Gene. 2005, 348 (1–2 SUPPL.): 111-121. 10.1016/j.gene.2004.12.053.

Koukidou M, Klinakis A, Reboulakis C, Zagoraiou L, Tavernarakis N, Livadaras I, Economopoulos A, Savakis C: Germ line transformation of the olive fly Bactrocera oleae using a versatile transgenesis marker. Insect Molecular Biology. 2006, 15 (1): 95-103. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00613.x.

Bruford MW, Wayne RK: Microsatellites and their application to population genetic studies. Current Opinion in Genetics and Development. 1993, 3 (6): 939-943. 10.1016/0959-437X(93)90017-J.

Schlötterer C, Pemberton J: The use of microsatellites for genetic analysis of natural populations. EXS. 1994, 69: 203-214.

Tautz D, Schlötterer C: Simple sequences. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994, 4: 832-837. 10.1016/0959-437X(94)90067-1.

Bonizzoni M, Malacrida AR, Guglielmino CR, Gomulski LM, Gasperi G, Zheng L: Microsatellite polymorphism in the mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata. Insect Molecular Biology. 2000, 9 (3): 251-261. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00184.x.

Bonizzoni M, Zheng L, Guglielmino CR, Haymer DS, Gasperi G, Gomulski LM, Malacrida AR: Microsatellite analysis of medfly bioinfestations in California. Molecular Ecology. 2001, 10 (10): 2515-2524. 10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01376.x.

Bonizzoni M, Guglielmino CR, Smallridge CJ, Gomulski M, Malacrida AR, Gasperi G: On the origins of medfly invasion and expansion in Australia. Molecular Ecology. 2004, 13 (12): 3845-3855. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02371.x.

Gasperi G, Bonizzoni M, Gomulski LM, Murelli V, Torti C, Malacrida AR, Guglielmino CR: Genetic differentiation, gene flow and the origin of infestations of the medfly, Ceratitis capitata. Genetica. 2002, 116: 125-135. 10.1023/A:1020971911612.

Stratikopoulos EE, Augustinos AA, Petalas YG, Vrahatis MN, Mintzas A, Mathiopoulos KD, Zacharopoulou A: An integrated genetic and cytogenetic map for the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata, based on microsatellite and morphological markers. Genetica. 2008, 133: 147-157. 10.1007/s10709-007-9195-9.

Song SD, Drew RAI, Hughes JM: Multiple paternity in a natural population of a wild tobacco fly, Bactrocera cacuminata (Diptera: Tephritidae), assessed by microsatellite DNA markers. Molecular Ecology. 2007, 16 (11): 2353-2361. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03277.x.

Bonizzoni M, Katsoyannos BI, Marguerie R, Guglielmino CR, Gasperi G, Malacrida A, Chapman T: Microsatellite analysis reveals remating by wild Mediterranean fruit fly females, Ceratitis capitata. Molecular Ecology. 2002, 11 (10): 1915-1921. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01602.x.

Kraaijeveld K, Katsoyannos BI, Stavrinides M, Kouloussis NA, Chapman T: Remating in wild females of the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata. Animal Behaviour. 2005, 69 (4): 771-776. 10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.06.015.

Augustinos AA, Stratikopoulos EE, Zacharopoulou A, Mathiopoulos KD: Polymorphic microsatellite markers in the olive fly, Bactrocera oleae. Molecular Ecology Notes. 2002, 2 (3): 278-280. 10.1046/j.1471-8286.2002.00222.x.

Bachtrog D, Weiss S, Zangerl B, Brem G, Schlötterer C: Distribution of dinucleotide microsatellites in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Mol Biol Evol. 1999, 16 (5): 602-610.

Katti MV, Ranjekar PK, Gupta VS: Differential distribution of simple sequence repeats in eukaryotic genome sequences. Mol Biol Evol. 2001, 18 (7): 1161-1167.

Schug MD, Wetterstrand KA, Gaudette MS, Lim RH, Hutter CM, Aquadro CF: The distribution and frequency of microsatellite loci in Drosophila melanogaster. Molecular Ecology. 1998, 7: 57-70. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00304.x.

Hutter CM, Schug MD, Aquadro CF: Microsatellite variation in Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila simulans: A reciprocal test of the ascertainment bias hypothesis. Mol Biol Evol. 1998, 15 (12): 1620-1636.

Zheng L, Benedict MQ, Cornel AJ, Collins FH, Kafatos FC: An integrated genetic map of the African human malaria vector mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Genetics. 1996, 143: 941-952.

Estoup A, Solignac M, Harry M, Cornuet J: Characterization of (GT)(n) and (CT)(n) microsatellites in two insect species: Apis mellifera and Bombus terrestris. Nucleic Acids Research. 1993, 21 (6): 1427-1431. 10.1093/nar/21.6.1427.

Kinnear MW, Bariana HS, Sved JA, Frommer M: Polymorphic microsatellite markers for population analysis of a tephritid pest species, Bactrocera tryoni. Molecular Ecology. 1998, 7 (11): 1489-1495. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00480.x.

Reddy KD, Abraham EG, Nagaraju J: Microsatellites in the silkworm, Bombyx mori: Abundance, polymorphism, and strain characterization. Genome. 1999, 42 (6): 1057-1065. 10.1139/gen-42-6-1057.

Noor MAF, Schug MD, Aquadro CF: Microsatellite variation in populations of Drosophila pseudoobscura and Drosophila persimilis. Genetical Research. 2000, 75 (1): 25-35. 10.1017/S0016672399004024.

Harr B, Schlötterer C: Patterns of microsatellite variability in the Drosophila melanogaster complex. Genetica. 2004, 120 (1–3): 71-77. 10.1023/B:GENE.0000017631.00820.49.

Rubinsztein DC, Amos W, Leggo J, Goodburn S, Jain S, Li S, Margolis RL, Ross CA, Ferguson-Smith MA: Microsatellite evolution – Evidence for directionality and variation in rate between species. Nature Genetics. 1995, 10 (3): 337-343. 10.1038/ng0795-337.

Segura MD, Callejas C, Fernaìndez MP, Ochando MD: New contributions towards the understanding of the phylogenetic relationships among economically important fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae). Bulletin of Entomological Research. 2006, 96 (3): 279-288. 10.1079/BER2006425.

Han HY: Molecular phylogenetic study of the tribe Trypetini (Diptera: Tephritidae), using mitochondrial 16S ribosomal DNA sequences. Biochemical systematics and Ecology. 2000, 120: 501-513. 10.1016/S0305-1978(99)00097-6.

Han HY, McPheron BA: Molecular phylogenetic study of tephritidae (insecta: diptera) using partial sequences of the mitochondrial 16S ribosomal DNA. Molecular phylogenetics and Evolution. 1997, 7: 17-32. 10.1006/mpev.1996.0370.

Han HY, McPheron BA: Phylogenetic study of selected Tephritid flies (Insecta: Diptera: Tephritidae) using partial sequences of the nuclear 18s ribosomal DNA. Biochemical systematics and Ecology. 1994, 22: 444-457. 10.1016/0305-1978(94)90040-X.

Chirhart SE, Honeycutt RL, Greenbaum IF: Microsatellite variation and evolution in the Peromyscus maniculatus species group. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2005, 34 (2): 408-415. 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.10.018.

Goldstein DB, Pollock DD: Launching microsatellites: A review of mutation processes and methods of phylogenetic inference. Journal of Heredity. 1997, 88 (5): 335-342.

Schlötterer C: Genealogical inference of closely related species based on microsatellites. Genetical Research. 2001, 78: 209-212. 10.1017/S0016672301005444.

Kounatidis I, Papadopoulos N, Bourtzis K, Mavragani-Tsipidou P: Genetic and cytogenetic analysis of the fruit fly Rhagoletis cerasi (Diptera: Tephritidae). Genome. 2008, 51 (7): 479-491. 10.1139/G08-032.

Zacharopoulou A: Polytene chromosome maps in the Medfly Ceratitis capitata. Genome. 1990, 33: 184-197.

Zacharopoulou A, Frisardi M, Savakis C, Robinson AS, Tolias P, Konsolaki M, Komitopoulou K, Kafatos FC: The genome of the Mediterranean fruit fly C. capitat a: Localization of molecular markers by in situ hybridization to salivary gland polytene chromosomes. Chromosoma. 1992, 101: 448-455. 10.1007/BF00582839.

Tsitsipis JA: An improved method for the mass rearing of the olive fruit fly, Dacus oleae (Gmel.) (Diptera, Tephritidae). Z Angrew Entomol. 1977, 83: 419-426.

Tsitsipis JA: Development of a caging and egging system for mass rearing the olive fruit fly, Dacus oleae (Gmel.) (Diptera, Tephritidae). Ann Zool Ecol Anim. 1977, 9: 133-139.

Tzanakakis ME, Economopoulos AP, Tsitsipis JA: The importance of conditions during the adult stage in evaluating an artificial food for larvae of Dacus oleae (Gmel.) (Diptera, Tephritidae). Z Angew Entomol. 1967, 59: 127-130.

Ashburner M: Drosophila: A Laboratory Manual. 1989, New York: Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory Press

Sambrook J, Fritch EF, Maniatis T: Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 1989, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. 21: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory press

Schlötterer C: Microsatellites. Molecular Genetic Analysis of Populations: a practical approach. Edited by: Hoelzel AR. 1998, Oxford University Press, 238-245.

Zambetaki A, Zacharopoulou A, Scouras ZG, Mavragani-Tsipidou P: The genome of the olive fruit fly Bactrocera oleae: Localization of molecular markers by in situ hybridization to the salivary gland polytene chromosomes. Genome. 1999, 42 (4): 744-751. 10.1139/gen-42-4-744.

Zheng L: Microsatellite mapping of insect genomes. Molecular Biology of Insect Disease Vectors: A methods manual. Edited by: Crampton JM, Beard CB, Louis C. 1997, Chapman & Hall, 321-329.

Yeh FC, Yang RC, Boyle TBJ, Ye ZH, Mao JX: POPGENE, the user-friendly shareware for population genetic analysis. 1997, Molecular Biology and Biotechnology Centre, University of Alberta, Canada

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant of the Hellenic General Secretariat of Research and Technology (99 EΔ529). AAA and EES were supported by a Fellowship from the National Fellowship Foundation (Greece). We would like to thank Dr Alan Robinson for providing C. fasciventris, A. ludens, B. dorsalis, B. correcta, B. cucurbitae samples, Dr M. Frommer for B. tryoni and the Campaña Nacional Contra Moscas de la Fruta, Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico, for providing A. oblique, A. serpentine, A. striata and A. fraterculus.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

AAA isolated the microsatellite markers, performed most of the analysis described in the manuscript and drafted the largest part of the manuscript. EES participated in the isolation of the microsatellite markers and developed the C. capitata markers. ED carried out the in situ hybridisations and helped to draft the manuscript. EGK participated in the cross-species analysis. PMT analysed the in situ hybridisation results and helped to draft the manuscript. AZ participated in the design of the study, hosted most of the research performed in her laboratory and helped to draft the manuscript. KDM participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Augustinos, A.A., Stratikopoulos, E.E., Drosopoulou, E. et al. Isolation and characterization of microsatellite markers from the olive fly, Bactrocera oleae, and their cross-species amplification in the Tephritidae family. BMC Genomics 9, 618 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-9-618

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-9-618