Abstract

The highest parts of the Dinaric Mountains along the eastern Adriatic coast of the southern Europe, known for their typical Mediterranean karst-dominated landscape and very humid climate, were glaciated during the Late Pleistocene. Palaeo-piedmont type glaciers that originated from Čvrsnica Mountain (2226 m a.s.l.; above sea level) in Bosnia and Herzegovina deposited hummocky, lateral and terminal moraines into the Blidinje Polje. We constrained the timing of the largest recognized glacier extent on Svinjača and Glavice piedmont glaciers by applying the cosmogenic 36Cl surface exposure dating method on twelve boulder samples collected from lateral, terminal and hummocky moraines. Using 40 mm ka–1 bedrock erosion rate due to high precipitation rates, we obtained 36Cl ages of Last Glacial Maximum (LGM; 22.7 ± 3.8 ka) from the hummocky moraines, and Younger Dryas (13.2 ± 1.8 ka) from the lateral moraine in Svinjača area. The amphitheater shaped terminal moraine in Glavice area also yielded a Younger Dryas (13.5 ± 1.8 ka) age within the error margins. Our results provide a new dataset, and present a relevant contribution towards a better understanding of the glacial chronologies of the Dinaric Mountains. Because our boulder ages reflect complex exhumation and denudation histories, future work is needed to better understand these processes and their influence on the cosmogenic exposure dating approach in a karstic landscape.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Dinaric Mountains extend along the eastern Adriatic coast for about 650 km along the western Balkan Peninsula, from the Alps in Slovenia to the Korab Mountains in Albania, and is highly influenced by the Mediterranean climate. Western part of the mountain range is a karst landscape with high-elevated plateaux, which characterizes highest segments of the Dinaric Mountains with elevations reaching 2522 m a.s.l. (above sea level) in Durmitor and 2694 m a.s.l. in Prokletije Mountains, where small glaciers still exist (Gachev et al. 2016). The Dinaric Mountains were also glaciated in the past. First studies related to the glaciations of the Dinaric Mountains were carried out in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro (e.g., Cvijić 1899; Grund 1902, 1910; Penck 1900; Liedtke 1962; Riđanović 1966). Pleistocene glaciers were reported from the coastal Dinaric Mountains bordering the Adriatic Sea (Cvijić 1899, 1900). Because of likely high moisture supply during cold periods (e.g., Hughes et al. 2010), moraines were encountered below 1000 m a.s.l., and glacial deposits were described even at sea level in northern Dalmatia (Croatia) (Marjanac and Marjanac 2004). von Sawicki (1911) reported moraines on Mount Orjen (1894 m) in Montenegro, ~ 500 m a.s.l., overlooking present level of the Adriatic Sea. Although wars and political instabilities during the last century prevented further research in the countries surrounding the Dinaric Mountains, there is now an increasing interest in the description and understanding of past glacial deposits and events (e.g., Hughes et al. 2010, 2011; Petrović 2014; Krklec et al. 2015). For instance, the Late Pleistocene glacial landforms and glaciokarst of Mount Orjen were described in detail (Marković 1973; Stepišnik et al. 2009a, b). Ice caps and valley glaciers also developed elsewhere in the Dinaric Mountains, e.g., in the mountains of Albania (e.g., Milivojević 2007; Milivojević et al. 2008), Montenegro (e.g., Hughes et al. 2011), and Slovenia (e.g., Žebre and Stepišnik 2015a; Žebre et al. 2016).

Recent interest is focussed on the dating of glacial landforms and their palaeoclimatic interpretations. Although the U-series method lacks the precision needed to constrain the timing of moraine deposition, it can, nevertheless, bracket moraines within certain glacial cycles, where a first attempt was made on Mount Orjen (Hughes et al. 2010). By dating secondary cements within moraines and outwash fans, Middle Pleistocene (MIS 12; 480–430 ka), and later MIS 6 (190–130 ka) and MIS 5d-2 (110–11.7 ka) glaciations were reported by Hughes et al. (2010). Cosmogenic 36Cl surface exposure dating is now a well-established method for dating moraines (Dunai 2010; Gosse and Phillips 2001), and became a standard tool in dating especially carbonate lithologies and carbonate-derived sediments (e.g., Gromig et al. 2018; Pope et al. 2015; Sarıkaya et al. 2014; Styllas et al. 2018). However, karst denudation rates in extremely moist climatic settings, such as in southwestern Bosnia and Herzegovina, where this study is carried out, limit the confidence in the 36Cl exposure dating technique to rocks older than ~ 40 ka (Hughes and Woodward 2017; Levenson et al. 2017 and references therein). A recent study in Bosnia and Herzegovina by Žebre et al. (2019) successfully tackled this challenging problem and obtained the first 36Cl ages from the Dinaric Mountains. A total of 20 moraine boulders yielded ages spanning from Oldest Dryas in Velež Mountain (14.9 ± 1.1 ka) to Younger Dryas in Crvanj Mountain (11.9 ± 0.9 ka) (Žebre et al. 2019).

This paper focuses on the glacial chronology of the Blidinje area in Bosnia and Herzegovina. We, therefore, aim (a) to overview the geomorphological evidence for glaciation in the Blidinje area; (b) to constrain the timing of the largest recognized glacier extent on Svinjača and Glavice piedmont glaciers by applying the cosmogenic 36Cl surface exposure dating method on lateral, terminal, and hummocky moraines; (c) to discuss the formation of hummocky moraines in a karstic landscape; and (d) to compare the existent chronology with the surrounding mountains in the Dinaric Mountains and also in wider Balkan Peninsula.

Regional setting

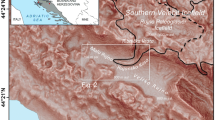

The Blidinje area (43°40′–43°35′N and 17°25′–17°40′E) is located in the central Dinaric Mountains in southern Bosnia and Herzegovina. The central lowered relief, known as Blidinje Polje (Blidinjsko Polje or Dugo Polje), was recently mapped and described by Stepišnik et al. (2016). Blidinje Polje is a southwest–northeast elongated polje ~ 20 km long and 2–5 km wide, surrounded by Vran Mountain (2074 m a.s.l.) to the northwest, and by Čvrsnica Mountain (2226 m a.s.l.) to the southeast. The study area is part of Bosnia and Herzegovina high karst (Buljan et al. 2005), mainly composed of more or less permeable Cretaceous and Jurassic carbonate rocks and their Quaternary re-depositions (Sofilj and Živanović 1979; Stepišnik et al. 2016).

According to the Köppen–Geiger climate classification (Kottek et al. 2006), the study area has characteristics of a warm temperate climate, fully humid, with cool summers (Cfc). The Blidinje area is located within a transition zone between the Mediterranean and continental climate. Precipitation is distributed throughout the year due to the moisture originating from the Adriatic Sea towards west as well as due to orographic precipitation effect. The closest comparable meteorological station is in Nevesinje (891 m a.s.l.), located ~ 40 km southeast, where mean annual precipitation over the period 1961–1990 was 1795 mm, while the mean annual air temperature for the same 30-year period was 8.6 °C (Data courtesy Federal Hydrometeorological Institute, Sarajevo). Precipitation amount at higher altitudes, such as the Blidinje area and surrounding mountains, is expected to reach more than 2000 mm per year (Vojnogeografski Institut 1969).

Methods

Geomorphological mapping

The geomorphological map of the Blidinje Polje (~ 100 km2) was performed in detail by Stepišnik et al. (2016), who used a 20-m-resolution digital elevation model (DEM), Google Earth images, and topographic maps at a scale of 1: 25,000 and orthophotos (Geoportal Web Preglednik 2016). Limited geomorphological and geological descriptions of the area (Milićević and Prskalo 2014; Milojević 1935; Roglić 1959), and maps of landmine contamination from the 1992–1995 war, obtained from Bosnia and Herzegovina Mine Action Centre, were also essential while performing the fieldwork. We based our study on the results of Stepišnik et al. (2016) and sampled two areas where the moraines were most promising for cosmogenic 36Cl surface exposure dating because of their degree of preservation.

Cosmogenic nuclide dating

In the karstic Blidinje Polje moraines, we applied 36Cl cosmogenic surface exposure dating method to estimate the retreat timing of the glaciers. The length of time that the boulder has been exposed on the moraine surfaces can be estimated using certain cosmogenic nuclides (such as 36Cl, 10Be, and 26Al) (Davis and Schaeffer 1955; Dunai 2010). Here, we used 36Cl, because the carbonates suit well to the production of 36Cl.

Dating carbonates with 36Cl depends on the interactions of secondary fast neutrons, thermal and epithermal neutrons, and negative slow muons with the nuclides in rocks (mainly, 40Ca, 39K, and 35Cl). Measured 36Cl concentrations in rocks can be used to quantify the time–length of boulder exposition (Gosse and Phillips 2001; Owen et al. 2001).

Sample collection and preparation

We collected 12 samples for cosmogenic 36Cl dating from the top of the boulders on the crests of lateral, terminal, and hummocky moraines. Large embedded boulders on moraine crests were preferred to sustain stability and preservation of boulders. We concentrated on the largest moraines that were reasonably away from the minefields and, hence, safe enough to accomplish the fieldwork. A few cm-thick rock samples were chipped out from boulder tops by hammer and chisel (Table 1). Shielding of surrounding topography was measured by inclinometer from the horizon at each sample location (Gosse and Phillips 2001).

The samples were prepared at Istanbul Technical University’s (ITU) Kozmo-Lab (http://www.kozmo-lab.itu.edu.tr/en) facility according to the procedures described in Sarıkaya (2009). The crushed samples at appropriate grain size (0.25–1 mm) were leached with deionized water and 10% HNO3 to remove secondary carbonates, dust, and organic particles. Aliquots of leached samples were used to measure the major and minor element concentrations at the Acme Lab (ActLabs Inc., Ontario Canada) (Table 2). Spiked (~ 99% 35Cl enriched Na35Cl from Aldrich Co., USA) samples were digested with excess amount of 2 M HNO3 in 500 ml HDPE bottles (Sarıkaya et al. 2014; Schlagenhauf et al. 2010). ~ 10 ml of 0.1 M AgNO3 solution was added before the digestion to precipitate AgCl. Sulfur was removed from the solution by repeated precipitation of BaSO4 with addition of Ba(NO3) and re-acidifying with concentrated HNO3. Final precipitates of AgCl were sent to the ANSTO, Accelerated Mass Spectrometer (AMS) in Sydney, Australia, for isotope ratio measurements given in Supplementary Table S1. Total Cl was determined by isotope dilution method (Desilets et al. 2006; Ivy-Ochs et al. 2004) after the AMS analysis (Table 2).

Determination of 36Cl ages

The CRONUS Web Calculator version 2.0 (http://www.cronuscalculators.nmt.edu) (Marrero et al. 2016a) was used to calculate sample ages. Cosmogenic 36Cl production rates of Marrero et al. (2016b) [56.3 ± 4.6 atoms 36Cl (g Ca)−1 a−1 for Ca spallation, 153 ± 12 atoms 36Cl (g K)−1 a−1 for K spallation and 743 ± 179 fast neutrons (g air)−1 a−1] were scaled using the time-dependent Lifton–Sato–Dunai schema (also called “LSD” or “SF” scaling) (Lifton et al. 2014). We used 190 µ g−1 a−1 for slow negative muon stopping rate at land surface at sea-level high latitude (Heisinger et al. 2002). ~ 95% of 36Cl production is due to the spallation and negative muon capture reactions on 40Ca. Because of the low Cl concentration of our samples (< 57 ppm), thermal neutron capture reactions by 35Cl constitute only ~ 5% of the total 36Cl production. Lower Ca spallation production rates suggested by Stone et al. (1996) or Schimmelpfennig et al. (2011) will make our ages ~ 10% older. All essential information to reproduce resultant ages is given in Supplementary Table S1.

All surface exposure ages include corrections for thickness and topographic shielding. We reported both zero erosion and 40 mm ka−1 erosion corrected boulder ages and preferred to use the latter, as the study area is located in one of the highest precipitation regions of Europe (> 2000 mm year−1), and boulder surfaces show up to several cm deep solution grooves. Snow thicknesses were estimated based on meteorological data from the Nevesinje weather station (Data courtesy Federal Hydrometeorological Institute, Sarajevo) (Table 3). Thus, snow correction factor for spallation reactions of 0.9539 was applied to all samples based on snowpack of 25, 100, 100, 100, 50, and 25 cm of snow on Nov, Dec, Jan, Feb, Mar, and Apr on top of boulders (Table 3) using the snow density of 0.25 g cm−3, and spallation attenuation length of 170 g cm−2. Please note that these estimates are minimum snowpack values, since the precipitation at sampling elevations might be higher that the precipitation measurements at Nevesinje station. Doubling the snowpack makes the correction factor 0.9131, and makes the ages ~ 9% older.

Results

Glacial geomorphology

The Blidinje Polje is filled with different types of sediments derived from the steep slopes of Vran Mountain (2074 m a.s.l.) to the northwest and Čvrsnica Mountain (2226 m a.s.l.) to the southeast (Fig. 1). In detail, the Blidinje Polje can be further classified as a border-type polje because of inflows from fluviokarst areas as well as a piedmont-type polje due to former inflows from glaciated areas (Ford and Williams 2007; Gams 1978). The Blidinje Lake (1180 m a.s.l.) in the south has abrasion terraces up to 7 m above the mean lake level indicating its larger extent in the past. The reader is referred to Stepišnik et al. (2016) for a detailed geomorphological map and description of the Blidinje Polje and surrounding areas. Postglacial subsurface drainage into karst is well developed in the areas of palaeoglaciers; therefore, products of past glaciations are well preserved (Smart 2004; Žebre and Stepišnik 2015a, b). Glacial deposits in form of lateral, terminal and hummocky moraines, mostly in north and northwest facing slopes of Vran and Čvrsnica mountains, are present in the study area (Stepišnik et al. 2016). Few km2 large proglacial fans, with glacial outwash sediments, are also found just below these moraines. Out of six major moraine depositional areas, we have chosen only two sample areas, where moraines were most promising for a chronological reconstruction. The presence of different types of moraines, boulder availability and accessibility, and clear evidence of multiple glacial advances also influenced our choice.

Svinjača area

The area southwest of Blidinje Polje is known as Svinjača and is surrounded by the foothills of Vran Mountain to the north and western Čabulja Mountain to the south (Stepišnik et al. 2016) (Fig. 2). Svinjača area is ~ 3.5 km long and up to 1.5 km wide, with a flat floor at an elevation of ~ 1170 m. A palaeoglacier, ~ 6 km long, that originated from a small ice cap (estimated to ~ 8 × 5 km) above 1400 m a.s.l., occupied the glacial valley at the southwestern part of the Čvrsnica Mountain, and is responsible for the deposition of the hummocky moraines found at Svinjača area (Fig. 3a). The hummocky moraine morphology left behind by gradually melting piedmont glacier is characterized by more or less equally distributed, randomly oriented chaotic mounds and depressions, which do not show any specific organization (e.g., knob-and-kettle topography described by Gravenor and Kupsch 1959). Up to 10 m high and 10–50 m wide mounds, with ~ 20° upper surface slopes, are separated by 10–50 m wide and several meters deep irregular depressions. Hummocky moraines are composed of Cretaceous limestone pebbles and cobbles (10–50 cm in diameter), but larger blocks of 1–3 m in diameter are also observed. The latter were preferred for sampling, although having signs of surface weathering. The depressions are filled by finer material and a thin veneer of black soil is present with grassy vegetation.

Geomorphological map of glacial landforms in the Svinjača area. Samples for 36Cl cosmogenic nuclide dating were collected from the hummocky (SV16-01–SL16-05) and left lateral (SV16-06–SL16-08) moraines. The samples IDs along with the ages (ka) corrected for 40 mm ka−1 of erosion are also shown on the map

Svinjača area moraines: a typical view of the hummocky moraines (HM) with knob-and-kettle topography. Blidinje Lake is seen at the horizon (photo looking to northeast), b left lateral (LLM) and hummocky moraines (HM) (photo looking to W), c exit of the glacial and the left lateral moraine (LLM) (photo looking to E), and d cross section of the lateral moraine with unsorted and unstratified limestone boulders floating in a sandy matrix. White and red arrows indicate palaeo-ice flow directions. Houses (a–c) and person (d) for scale

A left lateral moraine ~ 400 m long and ~ 30 m high (to 1265 m a.s.l.) is also found at the termination of the glacial valley (Fig. 3b–d). The lateral moraine extends from 1300 m a.s.l. down to 1265 m a.s.l., and is composed of diamicton characterized by unsorted and unstratified sandy–silty matrix with subangular-to-subrounded boulders of limestone.

At the northwestern limit of the palaeo-piedmont lobe, which is represented by the hummocky morphology, a proglacial fan, with flatter topography and finer grained sediments, covers a large section of the Svinjača floor. As no surface streams are found in the Svinjača depression, Stepišnik et al. (2016) interpreted the area as a combination of piedmont and border-type polje owing to the presence of fluviokarst and proglacial deposits filling the polje (Ford and Williams 2007; Gams 1978).

Glavice area

A typical amphitheater-shaped terminal moraine, here named as Glavice moraine, oriented in a southeast to northwest direction and ~ 3 km in diameter, constitutes one of the largest moraine complexes of the Blidinje Polje (Figs. 4, 5a–c). This moraine complex that descends down to 1260 m a.s.l. at its lowermost northeastern extent was probably deposited by a small outlet glacier originating from the Čvrsnica ice cap. Although the moraine is well preserved, dense dwarf mountain pine vegetation with a thick black soil cover makes a detailed observation and sampling rather difficult. Cretaceous and Jurassic limestone and dolostone boulders (1–3 m in diameter) can be observed between the trees, and were sampled when adequate. Today, two major but inactive streambeds, formed by proglacial streams flowing towards northwest, dissect the outer rim of the moraine loop. To the northwest and north of the moraine, outwash fans cover parts of Blidinje Polje.

Glavice terminal moraine pictures: a a typical amphitheater-shaped terminal moraine (overgrown by forest) covering the part of the Blidinje Polje (view from northeast towards southwest), b the frontal view of terminal moraine with Stećak-monumental Medieval (12th–15th century) tombstones found scattered across BIH, inscribed as UNESCO’s World Heritage Site since 2016—at the foreground, and c close-up view of the terminal moraines

36Cl exposure ages and Blidinje area chronology interpretation

We collected a total of 12 glacial boulder samples from Svinjača and Glavice areas for 36Cl cosmogenic nuclide dating purposes (Table 1). We used 40 mm ka−1 as the most representative erosion rate for the correction of all sample ages as denudation rates of carbonate rocks can be very high and are enhanced with increasing mean annual precipitation (MAP) (Levenson et al. 2017; Ryb et al. 2014). These seemingly high denudation rates are to be expected in areas where very high mean annual precipitations are observed (Levenson et al. 2017), such as Nevesinje nearby the study area. Comparable denudation rates (30–60 mm ka−1) were also measured in the Mediterranean karst in southeastern France (Thomas et al. 2018) independently of the precipitation amount. We preferred to use the same erosion rate as in Velež and Crvanj mountains (Žebre et al. 2019), only ~ 40 km away. However, we recognize that such high erosion rates (40 mm ka−1) will inevitably limit the confidence in the corrected ages, especially for older periods. We present age uncertainties at the 1-sigma level (i.e., one standard deviation), which include both the analytical and production rate errors (i.e., total uncertainties). We used the oldest moraine boulder age as the age of that landform, which represent the beginning of glacier retreat (Fig. 8).

Svinjača glacial chronology

Five samples from the hummocky moraines and three samples from the left lateral moraine were collected at the exit of the glacial valley (Fig. 6). The chemical analysis of all samples collected from this area is almost identical; limestone, showing similar concentrations of CaO (~ 55%) and very low K2O (0.01%) and Cl (5.6–12.8 ppm), and thus, the main production mechanism (> 97%) is spallation of Ca (Table 2, Supplementary Table S1). Five boulders from the hummocky moraines yielded 36Cl ages of 12.2 ± 1.4 ka (SV16-01), 22.7 ± 3.8 ka (SV16-02), 16.6 ± 2.4 ka (SV16-03), 16.4 ± 2.4 ka (SV16-04), and 22.5 ± 3.8 ka (SV16-05) (Table 4). The oldest moraine boulder age is 22.7 ± 3.8 ka and indicates the Last Glacial Maximum [LGM; the time period when ice masses reached their last maximum global extent at around 23–19 ka (Hughes et al. 2013)] as the retreat time of the piedmont glacier (Fig. 8). On the other hand, boulders from the left lateral moraine gave 36Cl ages of 10.6 ± 1.3 ka (SV16-06), 11.5 ± 1.5 ka (SV16-07), and 13.2 ± 1.8 ka (SV16-08) (Table 4). Here, the oldest moraine boulder age is 13.2 ± 1.8 ka, and indicates the moraine formation during the Younger Dryas Stadial within error. As expected, the left lateral moraine is younger than the hummocky moraines as it is found on higher elevation at the exit of the glacial valley.

Glavice glacial chronology

We also collected four samples from the terminal moraine of the Glavice area (Fig. 7). Boulders have similar carbonate lithologies (55% CaO) with slightly higher Cl concentrations (~ 37 ppm) than samples from Svinjača. Four boulders of the terminal moraine complex yielded 36Cl ages of 9.7 ± 1.1 ka (GL16-01), 8.2 ± 1.5 ka (GL16-02), 9.0 ± 1.0 ka (GL16-03), and 13.5 ± 1.8 ka (GL16-04) (Table 4). Here, we applied the same approach as in Svinjača and chose the oldest boulder age (13.5 ± 1.8 ka) from the terminal moraine as the most representative time of moraine emplacement. This age indicates the Younger Dryas Stadial within error in the Glavice area.

The proposed boulder and moraine ages should be considered as minimum ages as suggested also by the other studies (e.g., Ivy-Ochs and Schaller 2009; Lukas 2011; Lüthgens et al. 2011) (Fig. 8). We also think that the dated left lateral and terminal moraines in both areas belong to the same glacial period within error (Younger Dryas), not only because they have very close cosmogenic ages (13.2 ± 1.8 ka and 13.5 ± 1.8 ka, respectively), but also because they are found at similar elevations (~ 1300 m a.s.l.).

Cosmogenic 36Cl ages of the boulders from a hummocky moraines and left lateral (LLM) moraines of Svinjača and b terminal moraines of Glavice areas. Upper panels show the individual sample ages with 1-sigma uncertainties, and the lower panels show the probably density functions (PDF) of the samples. Oldest age of the moraines (indicated by thick PDF curves) from both data sets were shown and assigned to the age of the landforms

Discussion

Interpreting the moraine age from the boulders

Numerous studies suggest different approaches (i.e., taking the oldest boulder age within a cluster or weighted average age of boulders after the exclusion of outliers, etc.) for the interpretation of a moraine landform age from the dated boulders (e.g., D’Arcy et al. 2019; Applegate et al. 2010, 2012; Çiner et al. 2017; Davis et al. 1999; Dortch et al. 2013; Hallet and Putkonen 1994; Heyman et al. 2011; May et al. 2011; Putkonen and Swanson 2003; Žebre et al. 2019; Zech et al. 2017). In our study, we prefer to use the oldest boulder age as the most representative age of the landform, because exhumation and erosion of boulders are the main geological uncertainties to be considered while interpreting exposure ages in very humid environments, such as our study area. However, further discussion of these methods is out of the scope of this paper and we refer the readers to Žebre et al. (2019) for a detailed discussion related to this problematic, especially focused on the climatic conditions specific to the Dinaric Mountains. Other discussions on the interpretation of boulder ages within a moraine can be found in Palacios et al. (2019), and in the Appendix of D’Arcy et al. (2019).

Piedmont glaciers and hummocky moraines

The term “hummocky moraine” is very useful for describing the overall appearance of many areas of moraines in formerly glaciated areas (Hughes 2004). The supraglacial debris cover is at the origin of the hummocky moraines, which is a descriptive term that designates moundy, irregular morainic knob-and-kettle (convex and concave) topography (e.g., Gravenor and Kupsch 1959; Aario 1977; Sharp 1985; Çiner et al. 1999; Benn and Owen 2002). Hummocky moraines have been described in several locations in the world; e.g., in Scotland (Sissons 1967), in Turkey (Çiner 2003; Çiner et al. 1999, 2015; Sarıkaya and Çiner 2017), in Tajikistan (Zech et al. 2005), and in Norway (Knudsen et al. 2006).

Different interpretations exist about the formation of hummocky moraines; they can result from locally isolated patches of melting glaciers (Clapperton and Sugden 1977), melting of debris-covered ice in ice-cored moraines (Lukas 2011), or subglacial deformation of coarse debris including older till deposits (Hodgson 1982). For instance, Sissons (1967, 1979) described hummocky moraines in Scotland as “chaotic mounds that lack any systematic arrangement” and interpreted this as evidence of in situ glacier stagnation. This view was later challenged by several other studies, which argued that the hummocky moraine topography could be also formed by the decay of detached ice blocks from an actively retreating glacier (Eyles 1983; Bennett and Glasser 1991; Bennett and Boulton 1993; Bennett 1990, 1994). Hummocky moraines can be also the result of combined processes, such as in Lenin Peak (Pamir Mountains, Kyrgyzstan), where two different geomorphic events have been inferred from hummocky terrain (landslide, glacier) even if they look very similar (Oliva and Ruiz-Fernández 2018). Some authors even argue that hummocky moraines could also form subglacially by the overburden pressure of stagnant ice (e.g., Boone and Eyes 2001).

Hummocky accumulations in the Svinjača area are likely the result of the melting debris-covered glacier snout. Ice ablation caused transport of debris away from topographic heights on the glacier surface by mass movement resulting in an irregular mounds and ridges topography. Sedimentology of hummocky moraines is normally complex due to multiple cycles of re-deposition during their formation and parallel reworking with meltwater streams (Benn and Evans 2010). Lack of glaciofluvial and lacustrine deposits interbedded with supraglacial till in the outcrops in the case of Svinjača area is probably the result of reduced meltwaters action due to active vertical drainage into karst. In addition, part of knob-and-kettle topography in the area is due to suffusion process, where till is evacuated trough underlying pipes into karst (Ford and Williams 2007). Boulders from the hummocky moraines in the Svinjača area indicate the LGM as the formation time of the piedmont glacier. On the other hand, boulders from the left lateral moraine in the Svinjača area and terminal moraine in the Glavice area are younger and indicate a deglaciation during the Younger Dryas. Although a two-phase interpretation might hold true, we should also take into account different moraine degradation rates and their effect on the exhumation processes. Sharp-crested and steep lateral moraines are normally affected by higher degree of postglacial degradation and boulder exhumation than small, flat crested hummocky moraines (Applegate et al. 2010; Putkonen and Swanson 2003). As a result, the cosmogenic age does not always reflect a true moraine age, but, instead, the age of the boulder exhumation, especially in the case of steep lateral moraines.

It should also be noted that even though the oldest ages obtained from the lateral and terminal moraines in both areas overlap within error with the Younger Dryas Stadial, they could also fall within the preceding Allerød, which was a warm and moist interstadial that occurred between ~ 13.9 and ~ 12.9 ka ago. For instance, in Scotland’s last ice fields, a similar age data set was reinterpreted as indicating a larger Allerød glacier extent and retreat during the Younger Dryas Stadial (Bromley et al. 2014, 2018). However, as the Younger Dryas Stadial is recorded throughout the Mediterranean mountains glacial records (e.g. Çiner et al. 2017; Hughes et al. 2018), it seems likely that this was also the case in our study area.

Glacial chronologies in the Balkans

Glaciation extent of the western Balkan Mountains has been adequately studied, but there is relatively little morphochronologic data to associate with the Blidinje area. Some of the glacial records in the Balkans have been dated using U-series (Adamson et al. 2014; Hughes et al. 2006, 2007, 2010, 2011) that gives a minimum age for the glacial deposits by dating secondary carbonates, which are formed after the formation of the host moraines (Fig. 9, Table 5). Unlike U-series, cosmogenic dating has the potential to obtain the depositional age of a moraine and, thus, can provide a more precise geochronology for the Late Pleistocene glaciations. This method has been applied to some areas in the western and southern Balkans (Kuhlemann et al. 2009, 2013; Pope et al. 2015; Styllas et al. 2018). However, there is a considerable scatter in data set between and amongst U-series and cosmogenic dating (Table 5).

All locations in the Balkan Peninsula where moraines and outwash deposits have been dated so far. Base layer of mountain belts is from https://ilias.unibe.ch/goto.php?target=file_1049915, based on the mountain definition by Kapos et al. (2000). Bathymetric data are from the European Marine Observation and Data Network (http://www.emodnet.eu/), while the sea-level data for LGM and Younger Dryas are from Lambeck et al. (2011)

Recent studies using 36Cl cosmogenic dating from the adjacent massifs yielded ages spanning from Oldest Dryas (14.9 ± 1.1 ka) for the Velež Mountain to Younger Dryas (11.9 ± 0.9 ka) for the Crvanj Mountain with maximum extent of glacial deposits located as low as ~ 900 m a.s.l. (Žebre et al. 2019).

Another area where the 36Cl cosmogenic nuclide dating technique was used is Mount Chelmos in Greece, which yielded the last phase of moraine building within local cirques at the Younger Dryas to Early Holocene (13–10 ka). Lower glacial deposits at ~ 2100 m a.s.l. indicate that the glacial maximum of the last cold stage occurred during MIS 3 (40–30 ka), several thousand years before the global LGM at MIS 2 (Pope et al. 2015). On the contrary, ground moraines at the same elevation in a parallel valley yielded optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) ages of MIS-5b (89–86 ka) (Pavlopoulos et al. 2018). The lowest glacial deposits reaching elevations of ~ 1200 m a.s.l. were not dated, but they are assumed to be of Middle Pleistocene age (Pope et al. 2015). On Mount Olympus in Greece at an elevation of ~ 2200 m a.s.l., glacier retreat phases were dated within cirque moraines by 36Cl cosmogenic method that can be correlated to the Oldest Dryas (~ 15.5 ka) and Younger Dryas (~ 12.5 ka). Although there are no chronological data for the maximum glacial extent, the LGM moraines were assumed to be a short distance away at the entrance to the cirque (Styllas et al. 2018). The older Middle Pleistocene glaciations were found in much lower altitudes extending well beyond the high mountain area down to the piedmont (Smith et al. 1997).

Glacial chronologies, based on the cosmogenic nuclide dating, were established also for the Galičica, Šar Planina, and Pelister mountains in North Macedonia. In the Galičica Mountain, 36Cl ages of moraine boulders at an elevation of ~ 2050 m a.s.l. indicate a moraine formation in the course of the Younger Dryas (12.0 ± 0.6 ka), while moraines further down valley at an elevation of 1550 m a.s.l. were not dated (Gromig et al. 2018). Results of 10Be cosmogenic exposure dating applied to the cirque moraine in the Pelister Mountain (North Macedonia) at an elevation of 2215 m a.s.l. demonstrate the Oldest Dryas age (15.24 ± 0.85 ka), whereas stratigraphically older moraines were not dated (Ribolini et al. 2018). The age of moraine boulders in the Šar Planina Mountain was determined by 10Be cosmogenic exposure dating (Kuhlemann et al. 2009). The maximum glacier advances that reached elevations between 1100 and 1500 m a.s.l. were correlated to the LGM (22.5–20 ka). Moraines at altitudes between 1600 and 2200 m were linked with the Oldest Dryas (16.5–15 ka), while moraines at altitudes between 2100 and 2400 m with the Younger Dryas (~ 12 ka). Small local moraines at higher elevation, close to the crest, were tentatively attributed to the 8.2 ka event (Kuhlemann et al. 2009). 10Be cosmogenic exposure dating was used to date the moraine boulders also in the Rila Mountain in Bulgaria. The maximum glaciation extent at an elevation between 1150 and 2000 m a.s.l. yielded ages prior (~ 25 to 23 ka) and after (~ 18 to 16 ka) LGM (Kuhlemann et al. 2013).

U-series dating technique was applied to date glacial deposits in Montenegro and Greece, where the two largest most palaeoglacier extents were correlated with MIS 12 (480–430 ka) and MIS 6 (190–130 ka) Middle Pleistocene cold stages (Hughes et al. 2006, 2007, 2010, 2011). Glaciers of the last cold stage have been recorded only in the form of limited-extent cirque glaciers, which is consistent with the findings using the same dating technique from the northern Greece (Hughes et al. 2007).

Our glacial chronological data from the Blidinje area are in good agreement with the other cosmogenic nuclide dating data from other parts of the Balkan Peninsula. 36Cl ages from hummocky moraines in the Svinjača area indicate first-ever-reported LGM age of the glaciers in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which roughly correspond to the established cosmogenic 10Be chronologies from the Rila and Šar Planina mountains (Kuhlemann et al. 2009, 2013). Younger Dryas ages from the lateral and terminal moraines in Blidinje are in good agreement with the dating results from the Velež Mountain (Žebre et al. 2019), Mount Olympus (Styllas et al. 2018), and Galičica Mountains (Gromig et al. 2018).

In the future, special priority should be given to quartz-rich lithologies in the dating of moraine boulders in prevalently carbonate mountains in the Balkans; such was done by Ribolini et al. (2018) in Mount Pelister in North Macedonia. This would then test and verify 36Cl-based ages, and help to confirm the validity of 40 mm ka−1 erosion rate that we used in our study. On that regard, it is interesting to note that Mount Pelister’s quartz-rich schist moraines (no boulder erosion assumed) yield an Oldest Dryas age, whereas limestone moraines in very closely situated Galičica Mountains at similar altitude, where 5 mm ka−1 boulder erosion rate was assumed, are Younger Dryas in age (Gromig et al. 2018). Whether this difference is due to variations in lithologies and/or erosion rates, or indicates a real difference in glacial chronology is an open question that needs to be answered by future research. Therefore, it is clear that more quantitative age results are needed from neighboring countries to better understand the glacial history of the Dinaric Mountains.

Conclusions

The Blidinje Polje in the Dinaric Mountains of Bosnia and Herzegovina along the eastern Adriatic coast was glaciated during the Late Pleistocene. A piedmont glacier that originated from the Čvrsnica Mountain (2226 m a.s.l.) descended down to 1250 m in the Svinjača area, and covered a surface of ~ 1.5 km2. Hummocky and lateral moraines composed of limestone boulders up to 3 m in diameter, which were later deposited by the melting of this glacier lobe. Because of dissolution susceptible limestone lithology and very high precipitation in the area, we used 40 mm ka−1 bedrock erosion rate, and dated the moraine boulders by cosmogenic 36Cl surface exposure method. The results indicate the first-ever-reported LGM (22.7 ± 3.8 ka) extent of glaciers from the Dinaric Mountains in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The lateral moraine of this piedmont lobe apparently developed during the Younger Dryas (13.2 ± 1.8 ka) Stadial within error. Within the Blidinje Polje in Glavice area, another amphitheater-shaped terminal moraine, at similar altitudes, yielded a similar Younger Dryas (13.5 ± 1.8 ka) age within error, confirming the importance of this stadial in this part of Dinaric Mountains.

References

Aario R (1977) Classification and terminology of morainic landforms in Finland. Boreas 6:87–100

Adamson KR, Woodward JC, Hughes PD (2014) Glaciers and rivers: pleistocene uncoupling in a Mediterranean mountain karst. Quatern Sci Rev 94:28–43

Applegate PJ, Urban NM, Laabs BJC, Keller K, Alley RB (2010) Model Development Modeling the statistical distributions of cosmogenic exposure dates from moraines. Geosci Model Dev 3:293–307

Applegate PJ, Urban NM, Keller K, Lowell TV, Laabs BJC, Kelly MA, Alley RB (2012) Improved moraine age interpretations through explicit matching of geomorphic process models to cosmogenic nuclide measurements from single landforms. Quatarn Res 77:293–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.YQRES.2011.12.002

Benn DI, Evans DJA (2010) Glaciers and Glaciation. Rutledge, New York, p 802

Benn DI, Owen LA (2002) Himalayan glacial sedimentary environments: a framework for reconstructing and dating the former extent of glaciers in high mountains. Quatern Int 97–98:3–25

Bennett MR (1990) The deglaciation of Glen Croulin, Knoydart. Scott J Geol 26:41–46

Bennett MR (1994) Morphological evidence as a guide to deglaciation following the Loch Lomond Stadial: a review of research approaches and models. Scott Geogr Mag 110:24–32

Bennett MR, Boulton GS (1993) A reinterpretation of Scottish “hummocky moraine” and its significance for the deglaciation of the Scottish Highlands during the Younger Dryas or Loch Lomond Stadial. Geol Mag 130:301–318

Bennett MR, Glasser NF (1991) The glacial landforms of Glen Geusachan, Cairngorms: a reinterpretation. Scott Geogr Mag 107:116–123

Boone SJ, Eyes N (2001) Geotechnical model for great plains hummocky moraine formed by till deformation below stagnant ice. Geomorphology 38:109–124

Bromley GRM, Putnam AE, Rademaker KM, Lowell TV, Schaefer JM, Hall BL et al (2014) Younger Dryas deglaciation of Scotland driven by warming summers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111(17):6215–6219. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1321122111

Bromley G, Putnam A, Borns H Jr, Lowell T, Sandford T, Barrell D (2018) Interstadial rise and Younger Dryas demise of Scotland’s last ice fields. Paleoceanogr Paleoclimatol 33:412–429. https://doi.org/10.1002/2018PA003341

Buljan R, Zelenika M, Mesec J (2005) Park prirode Blidinje, prikaz geološke građe i stukturno–tektonskih odnosa [Geologic and tectonic settings of the park of nature Blidinje]. In: Čolak I (ed) Prvi međunarodni znanstveni simpozij Blidinje 2005. Građevinski fakultet Sveučilišta u Mostaru, Mostar, pp 11–24

Çiner A (2003) Sedimentary facies analysis and depositional environments of the Late Quaternary moraines in Geyikdağ (Central Taurus Mountains). Geol Bull Turkey 46(1):35–54 (in Turkish)

Çiner A, Deynoux M, Çörekçioğlu E (1999) Hummocky moraines in the Namaras and Susam valleys, Central Taurids, SW Turkey. Quatern Sci Rev 18(4–5):659–669

Çiner A, Sarıkaya MA, Yıldırım C (2015) Late Pleistocene piedmont glaciations in the Eastern Mediterranean; insights from cosmogenic 36Cl dating of hummocky moraines in southern Turkey. Quatern Sci Rev 116:44–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.03.017

Çiner A, Sarıkaya MA, Yıldırım C (2017) Misleading old age on a young landform? The dilemma of cosmogenic inheritance in surface exposure dating: Moraines vs. rock glaciers. Quat Geochronol 42:76–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.QUAGEO.2017.07.003

Clapperton CM, Sugden DE (1977) The late Devensian glaciation of North East Scotland. In: Gray JM, Lowe JJ (eds) Studies in the Scottish Lateglacial Environment. Pergamon, Oxford, pp 1–4

Cvijić J (1899) Glacijalne i morfološke studije o planinama Bosne, Hercegovine i Crne Gore (Glacial and Morphological Studies about Mountains of Bosnia, Herzegovina and Montenegro). Srpska kraljevska Akademija, Beograd, p 57

Cvijić J (1900) Karsna polja zapadne Bosne i Hercegovine (Die Karstpoljen in Westbosnien und in Herzegowina). Glas Srpske Kraljevske Akademije Nauka 59(1):59–182

D’Arcy M, Schildgen TF, Strecker MR, Wittmann H, Duesing W, Mey J, Tofelde S, Weissmann P, Alonso RN (2019) Timing of past glaciation at the Sierra de Aconquija, northwestern Argentina, and throughout the Central Andes. Quatern Sci Rev 204:37–57

Davis R, Schaeffer OA (1955) Chlorine-36 in nature. Ann N Y Acad Sci 62:107–121

Davis PT, Bierman PR, Marsella KA, Caffee MW, Southon JR (1999) Cosmogenic analysis of glacial terrains in the eastern Canadian Arctic: a test for inherited nuclides and the effectiveness of glacial erosion. Ann Glaciol 28:181–188. https://doi.org/10.3189/172756499781821805

Desilets D, Zreda M, Almasi PF, Elmore D (2006) Determination of cosmogenic 36Cl in rocks by isotope dilution: innovations, validation and error propagation. Chem Geol 233:185–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHEMGEO.2006.03.001

Dortch JM, Owen LA, Caffee MW (2013) Timing and climatic drivers for glaciation across semi-arid western Himalayan-Tibetan orogen. Quatern Sci Rev 78:188–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.QUASCIREV.2013.07.025

Dunai T (2010) Cosmogenic nuclides principles, concepts and applications in the earth surface sciences. Cambridge Academic Press, Cambridge

Eyles N (1983) Modern Icelandic glaciers as depositional models for hummocky moraines in the Scottish Highlands. In: Evenson EB, Schlüchter C, Rabassa J (eds) Tills and related deposits. Balkema, Rotterdam, pp 47–60

Ford D, Williams PD (2007) Karst hydrogeology and geomorphology. Wiley, Chichester, p 576

Gachev E, Stoyanov K, Gikov A (2016) Small glaciers on the Balkan Peninsula: state and changes in the last several years. Quat Int 415:33–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.QUAINT.2015.10.042

Gams I (1978) The polje: the problem of definition: with special regard to the Dinaric karst. Z Geomorphol 22(2):170–181

Geoportal Web Preglednik (2016) In: F.u.z.g.i.i.-p. poslove (Editor). Federalna Uprava za Geodetske i Imovinsko-Pravne Poslove, Sarajevo

Gosse JC, Phillips FM (2001) Terrestrial in situ cosmogenic nuclides: theory and application. Quatern Sci Rev 20:1475–1560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-3791(00)00171-2

Gravenor CP, Kupsch WO (1959) Ice-disintegration features in Western Canada. J Geol 67:48–64

Gromig R, Mechernich S, Ribolini A, Wagner B, Zanchetta G, Isola I, Bini M, Dunai TJ (2018) Evidence for a Younger Dryas deglaciation in the Galičica Mountains (FYROM) from cosmogenic 36Cl. Quatern Int 464:352–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2017.07.013

Grund A (1902) Neue Eiszeitspuren aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina. Globus 81:149–150

Grund A (1910) Beiträge zur Morphologie des Dinarischen Gebirges. In: Grund A (ed) Geographische Abhandlungen. B. G. Teubner, Berlin, p 230

Hallet B, Putkonen J (1994) Surface dating of dynamic landforms: young boulders on aging moraines. Science 265(5174):937–940. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.265.5174.937

Heisinger B, Lal D, Jull AJT, Kubik P, Ivy-Ochs S, Knie K, Nolte E (2002) Production of selected cosmogenic radionuclides by muons: 2. Capture of negative muons. Earth Planet Sci Lett 200:357–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(02)00641-6

Heyman J, Stroeven AP, Harbor JM, Caffee MW (2011) Too young or too old: evaluating cosmogenic exposure dating based on an analysis of compiled boulder exposure ages. Earth Planet Sci Lett 302:71–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EPSL.2010.11.040

Hodgson DM (1982) Hummocky and fluted moraines in parts of northwest Scotland. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Edinburgh

Hughes PD (2004) Quaternary glaciation in the Pindus Mountains, Northwest Greece. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cambridge, p 341

Hughes PD, Woodward JC (2017) Quaternary glaciation in the Mediterranean mountains: a new synthesis. Geol Soc Lond Spec Publ 433:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP433.14

Hughes PD, Woodward JC, Gibbard PL, Macklin MG, Gilmour MA, Smith GR (2006) The glacial history of the Pindus Mountains, Greece. J Geol 114:413–434. https://doi.org/10.1086/504177

Hughes PD, Gibbard PL, Woodward JC (2007) Geological controls on Pleistocene glaciation and cirque form in Greece. Geomorphology 88(3):242–253

Hughes PD, Woodward JC, van Calsteren PC, Thomas LE, Adamson KR (2010) Pleistocene ice caps on the coastal mountains of the Adriatic Sea. Quatern Sci Rev 29:3690–3708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.06.032

Hughes PD, Woodward JC, van Calsteren PC, Thomas LE (2011) The glacial history of the Dinaric Alps, Montenegro. Quatern Sci Rev 30:3393–3412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.08.016

Hughes P, Gibbard PL, Ehlers J (2013) Timing of glaciation during the last glacial cycle: evaluating the concept of a global “Last Glacial Maximum” (LGM). Earth Sci Rev 125:171–198

Hughes PD, Fink D, Rodés Á, Fenton CR, Fujioka T (2018) 10Be and 36Cl exposure ages and palaeoclimatic significance of glaciations in the High Atlas, Morocco. Quatern Sci Rev 180:193–213

Ivy-Ochs S, Schaller M (2009) Examining processes and rates of landscape change with cosmogenic radionuclides. Radioact Environ 6(16):231–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1569-4860(09)01606-4

Ivy-Ochs S, Synal H-A, Roth C, Schaller M (2004) Initial results from isotope dilution for Cl and 36Cl measurements at the PSI/ETH Zurich AMS facility. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res Sect B Beam Interact Mater Atoms 223–224:623–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NIMB.2004.04.115

Kapos V, Rhind J, Edwards M, Price M, Ravilious C (2000) Developing a map of the world’s mountain forests. In: Price M, Butt N (eds) Forests in sustainable mountain development: a report for 2000. CAB International, Wallingford, pp 4–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-3508-X_52

Knudsen CG, Larsen E, Sejrup HP, Stalsberg K (2006) Hummocky moraine landscape on Jæren, SW Norway—implications for glacier dynamics during the last deglaciation. Geomorphology 77:153–168

Kottek M, Grieser J, Beck C, Rudolf B, Rubel F (2006) World map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol Z 15:259–263. https://doi.org/10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130

Krklec K, Domínguez-Villar D, Perica D (2015) Depositional environments and diagenesis of a carbonate till from a Quaternary paleoglacier sequence in the Southern Velebit Mountain (Croatia). Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 436:188–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PALAEO.2015.07.004

Kuhlemann J, Milivojević M, Krumrei I, Kubik PW (2009) Last glaciation of the Šara Range (Balkan peninsula): increasing dryness from the LGM to the Holocene. Austr J Earth Sci 102(1):146–158

Kuhlemann J, Gachev E, Gikov A, Nedkov S, Krumrei I, Kubik P (2013) Glaciation in the Rila mountains (Bulgaria) during the Last Glacial Maximum. Quatern Int 293:51–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.QUAINT.2012.06.027

Lambeck K, Antonioli F, Anzidei M, Ferranti L, Leoni G, Scicchitano G, Silenzi S (2011) Sea level change along the Italian coast during the Holocene and projections for the future. Q Int 232:250–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2010.04.026

Levenson Y, Ryb U, Emmanuel S (2017) Comparison of field and laboratory weathering rates in carbonate rocks from an Eastern Mediterranean drainage basin. Earth Planet Sci Lett 465:176–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2017.02.031

Liedtke VH (1962) Vergletscherungsspuren und Periglazialerscheinungen am Südhang des Lovcen östlich von Kotor. Eiszeit Gegenw 13:15–18

Lifton N, Sato T, Dunai T Journal (2014) Scaling in situ cosmogenic nuclide production rates using analytical approximations to atmospheric cosmic-ray fluxes. Earth Planet Sci Lett 386:149–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EPSL.2013.10.052

Lukas S (2011) Ice-cored moraines. In: Singh V, Singh P, Haritashya UK (eds) Encyclopedia of snow, ice and glaciers. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 616–619

Lüthgens C, Böse M, Preusser F (2011) Age of the Pomerian ice-marginal position in northeastern Germany determined by Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating of glaciofluvial sediments. Boreas 40:598–615

Marjanac L (2012) Pleistocene glacial and periglacial sediments of Kvarner, northern Dalmatia and southern Velebit Mt. e evidence of Dinaric glaciation. PhD thesis. University of Zagreb

Marjanac L, Marjanac T (2004) Glacial history of the Croatian Adriatic and coastal Dinarides. In: Ehlers J, Gibbard PL (eds) Quaternary glaciations—extent and chronology. Part I: Europe. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 19–26

Marjanac L, Marjanac T, Mogut K (2001) Dolina Gumance u doba Pleistocena. Zb Dru stva za Povj Klana 6:321–330

Marković M (1973) Geomorfološka evolucija i neotektonika Orjena. Rudarsko Geološki Fakultet, Beograd, p 269

Marrero SM, Phillips FM, Borchers B, Lifton N, Aumer R, Balco G (2016a) Cosmogenic nuclide systematics and the CRONUScalc program. Quat Geochronol 31:160–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2015.09.005

Marrero SM, Phillips FM, Caffee MW, Gosse JC (2016b) CRONUS-Earth cosmogenic 36Cl calibration. Quat Geochronol 31:199–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2015.10.002

May J-H, Zech J, Zech R, Preusser F, Argollo J, Kubik PW, Veit H (2011) Reconstruction of a complex late Quaternary glacial landscape in the Cordillera de Cochabamba (Bolivia) based on a morphostratigraphic and multiple dating approach. Quat Res 76:106–118

Milićević M, Prskalo M (2014) Geomorfološki tragovi pleistocenske glacijacije na Čvrsnici [Geomorphological Traces of Pleistocene Glaciation of the Čvrsnica Massif]. e–Zbornik Elektronički Zbornik Radova Građevinskog Fakulteta:87–94

Milivojević M (2007) Glacijalni reljef na Volujaku sa Bio cem i Magli cem. In: Posebna Izdanja, Srpska Akademija Nauka i Umetnosti, Geografski Institut “Jovan Cviji c”, Knj. 68. Geografski institut “Jovan Cviji c” SANU, Beograd, p 130

Milivojević M, Menković L, Calić J (2008) Pleistocene glacial relief of the central part of Mt. Prokletije (Albanian Alps). Quat Int 190:112–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2008.04.006

Milojević BŽ (1935) Čvrsnica. Hrvatski Geografski Glasnik 6(1):17–23

Oliva M, Ruiz-Fernández J (2018) Late Quaternary environmental dynamics in Lenin Peak area (Pamir Mountains, Kyrgyzstan). Sci Total Environ 645:603–614

Owen LA, Gualtieri L, Finkel RC, Caffee MW, Benn DI, Sharma MC (2001) Cosmogenic radionuclide dating of glacial landforms in the Lahul Himalaya, northern India: defining the timing of Late Quaternary glaciation. J Quat Sci 16:555–563. https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.621

Palacios D, Gómez-Ortiz A, Alcalá-Reygosa J, Andrés N, Oliva M, Tanarro LM, Salvador-Franch F, Schimmelpfennig I, Léanni L, Team ASTER (2019) The challenging application of cosmogenic dating methods in residual glacial landforms: the case of Sierra Nevada (Spain). Geomorphology 325:103–118

Pavlopoulos K, Leontaritis A, Athanassas CD, Petrakou C, Vandarakis D, Nikolakopoulos K, Stamatopoulos L, Theodorakopoulou K (2018) Last glacial geomorphologic records in Mt Chelmos, North Peloponnesus, Greece. J Mt Sci 15(5):948–965

Penck A (1900) Die Eiszeitspuren auf der Balkanhalbinsel. Globus 78:133–178

Petrović AS (2014) A Reconstruction of the Pleistocene Glacial Maximum in the Žijovo Range (Prokletije Mountains, Montenegro). Acta Geogr Slov 54:256–269. https://doi.org/10.3986/AGS54202

Pope RJ, Hughes PD, Skourtsos E (2015) Glacial history of Mt Chelmos, Peloponnesus, Greece. Geol Soc Lond Spec Publ 433:211–236. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP433.11

Putkonen J, Swanson T (2003) Accuracy of cosmogenic ages for moraines. Quatern Res 59:255–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-5894(03)00006-1

Reimer PJ, Bard E, Bayliss A, Beck JW, Blackwell PG, Bronk Ramsey C, Buck CE, Cheng H, Edwards RL, Friedrich M, Grootes PM, Guilderson TP, Haflidason H, Hajdas I, Hatte C, Heaton TJ, Hoffmann DL, Hogg AG, Hughen KA, Kaiser KF, Kromer B, Manning SW, Niu M, Reimer RW, Richards DA, Scott EM, Southon JR, Staff RA, Turney CSM, van der Plicht J (2013) IntCal13 and Marine13 radiocarbon age calibration curves 0–50,000 years cal BP. Radiocarbon 55:1869–1887. https://doi.org/10.2458/azu_js_rc.55.16947

Ribolini A, Bini M, Isola I, Spagnolo M, Zanchetta G, Pellitero R, Mechernich S, Gromig R, Dunai T, Wagner B, Milevski I (2018) An oldest Dryas glacier expansion on Mount Pelister (Former Yugoslavian Republic of Macedonia) according to 10Be cosmogenic dating. J Geol Soc Lond 1:4. https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2017-038

Riđanović J (1966) Orjen—La montagne dinarique. Radovi geografskog instituta sveučilišta u Zagrebu. Geografski Institut, Prirodoslovno-Matematički Fakultet, Zagreb

Roglić J (1959) Prilog poznavanju glacijacije i evolucije reljefa planina oko srednje Neretve (Supplement to the Knowledge of Glaciation and Relief Evolution of the Mountains Near Middle Neretva River). Geografski Glasnik 21(1):9–34

Ryb U, Matmon A, Erel Y, Haviv I, Benedetti L, Hidy AJ (2014) Styles and rates of long–term denudation in carbonate terrains under a Mediterranean to hyper-arid climatic gradient. Earth Planet Sci Lett 406:142–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EPSL.2014.09.008

Sarıkaya MA (2009) Late Quaternary glaciation and paleoclimate of Turkey inferred from cosmogenic 36Cl dating of moraines and glacier modeling. PhD Thesis, University of Arizona, USA

Sarıkaya MA, Çiner A (2017) The late Quaternary glaciation in the Eastern Mediterranean. In: Hughes P, Woodward J (eds) Quaternary glaciation in the mediterranean mountains, vol 433. Geological Society of London Special Publication, London, p 289–305

Sarıkaya MA, Çiner A, Haybat H, Zreda M (2014) An early advance of glaciers on Mount Akdağ, SW Turkey, before the global Last Glacial Maximum; insights from cosmogenic nuclides and glacier modeling. Quatern Sci Rev 88:96–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.QUASCIREV.2014.01.016

Schimmelpfennig I, Benedetti L, Garreta V, Pik R, Blard P-H, Burnard P, Bourlès D, Finkel R, Ammon K, Dunai T (2011) Calibration of cosmogenic 36Cl production rates from Ca and K spallation in lava flows from Mt. Etna (38°N, Italy) and Payun Matru (36°S, Argentina). Geochim Cosmochim Acta 75:2611–2632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2011.02.013

Schlagenhauf A, Gaudemer Y, Benedetti L, Manighetti I, Palumbo L, Schimmelpfennig I, Finkel R, Pou K (2010) Using in situ Chlorine-36 cosmonuclide to recover past earthquake histories on limestone normal fault scarps: a reappraisal of methodology and interpretations. Geophys J Int 182:36–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.2010.04622.x

Sharp MJ (1985) Sedimentation and stratigraphy at Eyjabakkajøkull: an icelandic surging glacier. Quatern Res 24:268–284

Sissons JB (1967) The evolution of Scotland’s scenery. Oliver and Boyd, Edinburgh. Younger Dryas or Loch Lomond Stadial. Geol Mag 130:301–318

Sissons JB (1979) The Loch Lomond Stadial in the British Isles. Nature 280:199–203

Smart CC (2004) Glacierized and glaciated karst. In: Gunn J (ed) Encyclopedia of caves and karst science. Fitzroy Dearborn, New York, pp 804–809

Smith GW, Nance RD, Genes AN (1997) Quaternary glacial history of Mount Olympus. Geol Soc Am Bull 109:809–824

Sofilj J, Živanović M (1979) Osnovna geološka karta SFRJ. K 33–12, Prozor [Basic Geological Map of SFRJ. K 33–12, Prozor]. Savezni Geološki Zavod, Beograd

Stepišnik U, Ferk M, Kodelja B, Medenjak G, Mihevc A, Natek K, Žebre M (2009a) Glaciokarst of western Orjen. Cave Karst Sci 36:21–28

Stepišnik U, Ferk M, Kodelja B, Medenjak G, Mihevc A, Natek K, Žebre M (2009b) Glaciokarst of western Orjen, Montenegro. Cave Karst Sci Trans Br Cave Res Assoc 36(1):21–28

Stepišnik U, Grlj A, Radoš D, Žebre M (2016) Geomorphology of Blidinje, Dinaric Alps (Bosnia and Herzegovina). J Maps 12(S1):163–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2016.1187209

Stone JO, Allan GL, Fifield LK, Cresswell RG (1996) Cosmogenic chlorine-36 from calcium spallation. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 60:679–692. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(95)00429-7

Styllas MN, Schimmelpfennig I, Benedetti L, Ghilardi M, Aumaître G, Bourlès D, Keddadouche K (2018) Late-glacial and Holocene history of the northeast Mediterranean mountain glaciers—new insights from in situ-produced 36Cl-based cosmic ray exposure dating of paleo-glacier deposits on Mount Olympus, Greece. Quatern Sci Rev 193:244–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.06.020

Thomas F, Godard V, Bellier O, Benedetti L, Ollivier V, Rizza M, Guillou V, Hollender F, Aumaître G, Bourlès DL, Keddadouche K (2018) Limited influence of climatic gradients on the denudation of a Mediterranean carbonate landscape. Geomorphology 316:44–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GEOMORPH.2018.04.014

Vojnogeografski Institut (1969) Atlas klime Socijalističke Federativne Republike Jugoslavije

von Sawicki L (1911) Die eiszeitliche Vergletscherung des Orjen in Süddalmatien. Z Gletscherkunde 5:339–355

Woodward JC, Macklin MG, Smith GR (2004) Pleistocene glaciation in the mountains of Greece. In: Ehlers J, Gibbard PL (eds) Quaternary glaciations—extent and chronology. Part I: Europe. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 155–173

Žebre M, Stepišnik U (2015a) Glaciokarst geomorphology of the Northern Dinaric Alps: Snežnik (Slovenia) and Gorski Kotar (Croatia). J Maps. https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2015.1095133

Žebre M, Stepišnik U (2015b) Glaciokarst landforms and processes of the southern Dinaric Alps. Earth Surf Process Landf 40:1493–1505. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.3731

Žebre M, Stepišnik U, Colucci RR, Forte E, Monegato G (2016) Evolution of a karst polje influenced by glaciation: the Gomance piedmont polje (northern Dinaric Alps). Geomorphology 257:143–154

Žebre M, Sarıkaya MA, Stepišnik U, Yıldırım C, Çiner A (2019) First 36Cl cosmogenic moraine geochronology of the Dinaric mountain karst: velež and Crvanj Mountains of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Quatern Sci Rev 208:54–75

Zech R, Glaser B, Sosin P, Kubik PW, Zech W (2005) Evidence for long-lasting landform surface instability on hummocky moraines in the Pamir Mountains (Tajikistan) from 10Be surface exposure dating. Earth Planet Sci Lett 237:453–461

Zech J, Terrizzano C, García-Morabito E, Veit H, Zech R (2017) Timing and extent of late pleistocene glaciation in the arid central Andes of Argentina and Chile (22–41_S). Geogr Res Lett 43:697–718

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Istanbul Technical University Research Fund (project MGA-2017-40540), by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TÜBİTAK-118Y052), by the Slovenian Research Agency (research core funding no. P1-0011, P6-0229(A) and P1-0025), and by the Department of Geography, University of Ljubljana. Nevesinje climate data are provided courtesy of the Federal Hydrometeorological Institute, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. We are very thankful to Klaus Wilcken at the ANSTO Lab in Australia for AMS measurements. We also acknowledge laboratory assistance of Oğuzhan Köse (Istanbul Technical University). We thank reviewers Marc Oliva and Philip Hughes, and editor Catherine Kuzucuoğlu for their helpful suggestions that improved the quality of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Çiner, A., Stepišnik, U., Sarıkaya, M.A. et al. Last Glacial Maximum and Younger Dryas piedmont glaciations in Blidinje, the Dinaric Mountains (Bosnia and Herzegovina): insights from 36Cl cosmogenic dating. Med. Geosc. Rev. 1, 25–43 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42990-019-0003-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42990-019-0003-4