Abstract

This study provides a behavior-analytic framework for a previous nudging experiment from Kallbekken and Sælen (Economics Letters 119(3), 325–327, 2013). We are concerned with achieving societal well-being from a selection-of-cultures perspective, and we call for increasing synergies between the 2 fields. The original experiment achieved a 20% reduction in food waste among restaurant customers by implementing 2 independent nudges: reducing plate size and socially approving multiple servings. We use this experiment as an example to introduce an analysis of the social contingencies (metacontingencies) responsible for not only establishing but also maintaining sustainable behavioral repertoires. We show how reducing food waste can be a simple, economic, effective example of a behavioral intervention when programmed with contingencies of cooperation. Furthermore, we generalize our model to social architectures that create and sustain cultural practices. Namely, our model addresses the long-term effects of nudging as a result of cooperation between stakeholders and how these effects are maintained by feedback loops. Whereas the aggregate effect of individual choice behavior can affect food consumption significantly, it may not suffice to change an enduring cultural practice. We argue that a behavior-analytic approach in studying complex systems informs nudging applications at the policy-making level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Addressing some of the most prolific, difficult, and expensive social problems affecting our health, labor and environmental policies call for adopting behavioral solutions (Halpern, 2015; Obama, 2006; OECD, 2017a). Consequently, numerous government-affiliated units and networks have been established to apply findings from behavioral economics. The policies derived from nudge theory aim to improve citizens’ policy-regulated behavior. Some of the most well-known governmental units include the Behavioral Insights Team in Westminster, London (established 2010); the New South Wales Behavioral Insights Team in Australia (2012); the Social and Behavioral Sciences Team in Washington, DC (2015); and the Qatar Behavioral Insights Unit (2016). We are clearly witnessing an endeavor toward achieving large-scale and sustainable change by submitting to a behavioral perspective in governmental policy making and regulation (OECD, 2017b). A thorough overview of the positive impact of a behavioral approach in consumer protection, environment, education, health, and other areas may be retrieved from the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2017a).

We stress the challenge of sustaining behavioral interventions in not only initiating but also maintaining socially responsible behavior. For the purpose of this study, we consider socially responsible behavior to be a synonym of cooperation, specifically implied by (a) interdependency between agents and (b) a dual-feedback process (internal and external). The concept of metacontingency (Glenn, 1986) best captures the cooperation among stakeholders to achieve positive and lasting societal solutions. A metacontingency is the functional relationship between the product of coordinated individual behaviors and their selecting contingencies—for example, the system that receives it.

We illustrate our model by fitting it to an example of cooperation aimed at nudging less food waste in a supplier–consumer context. The original study bears important policy implications on portion size, response cost efficiency, and environmental footprints. Nonetheless, we may have chosen any other example of nudging involving both interdependent behavior and feedback loops. For instance, behavioral insights were used to address the overprescribing of antibiotics in health policy (OECD, 2017a, p. 265) and the gender gap recruitment biases in labor policy (Bohnet, van Geen, & Bazerman, 2016).

The Need for a Behavioral Perspective Encompassing Social Issues

The attempt to influence behavior through environmental manipulation dates from long before the term nudge was formally introduced by Thaler and Sunstein (2008). The authors define a nudge as a soft form of paternalism, a guided-choice behavior, with specific characteristics. Choice architecture refers to the intrinsic properties of the natural environment and the social context in which choice behavior takes place. The architecture cannot be avoided because choice must be arranged in some way and is likely to influence our decisions (Sunstein, 2014). One of the most striking characteristics of the nudge concept is its “massive lack of originality” (anonymous, personal communication, May 26, 2017). Nevertheless, nudges seem to possess large effect sizes (Benartzi et al., 2017), social impact (OECD, 2017b), and diffusion (Benartzi et al., 2017; Sunstein, Reisch, & Rauber, 2017; Thaler & Sunstein, 2008).

Drawing on the definitions of choice architecture, we introduce the term social architecture to identify the arrangement of interdependent contingencies of behavior that compose sustainable cultural practices. Whereas coordinated behaviors may be fortuitously selected (for good or bad), cooperation often refers to intentionally acting together toward a common goal. In designing a social architecture, we endorse the latter sense of cooperation, whereas the more technical description of a metacontingency refers to coordinated behaviors selected by the contingencies (not necessarily the receiving system).

It is plausible that cases of “subtle” nudges, or sludges (Thaler, 2018) may outweigh nudging ethical behavior, and they may be more common than nudges for (our own) good. Sludges fulfill the economic or self-serving interests of the choice architect—that is, the designer of nudging interventions. For example, the European Commission recently banned preticked boxes for the sale of additional products through web portals (European Commission, 2014). Online marketers have been nudging us for some 20 years since the Internet was born, even though the term nudge did not exist at the time. In the absence of the regulation provided by this ban, online sellers were permitted to push sales by way of defaulting, which is the most effective and preferred nudge (Sunstein, 2014, 2016). Choice architects operate not only in traditionally for-profit domains (e.g., marketing, finance, manufacturing) but also in political, governmental, and social settings. For example, the city of Boston engaged in a yearlong initiative to increase trust in governmental services through operational transparency (OECD, 2017a, p. 322).

Behavior-analytic studies rarely cite the term nudge, insofar as arranging the architecture of choice means arranging contingencies of reinforcement (Tagliabue, Sandaker, & Ree, 2017). When contingencies are not possible (Alavosius, Getting, Dagen, Newsome, & Hopkins, 2009; Geller, 1989; Keller, 1991), nudges help manage organizational behavior through cooperation. Alavosius et al. (2009) implemented an incentive system in cooperatives to decrease work-related injuries. The authors call for an integration of behavioral system analysis and organizational behavior management in order to “produce lasting and significant benefit to large collectives of organizations” (Alavosius et al., 2009, p. 209). Capitalizing on the cooperation between members of a culture or community contributed to the good of the commonwealth: “Contingencies operating on one individual interplay with contingencies for others such that their combined efforts yield benefit to all” (Alavosius et al., 2009, p. 195).

A behavior-analytic approach to nudging may therefore interpret choice architecture as a form of arranging individual behavioral contingencies. Alternatively, we may interpret nudges through cultural selection as a form of arranging contingencies of cooperative behavior comprising cultural repertoires. Creating win–win interdependent behavioral repertoires between stakeholders sets the premises for sustainable behavioral change and maintenance (Biglan, 2015).

We illustrate this point by presenting a nudging experiment as an example of cooperation toward achieving environmental sustainability (Kallbekken & Sælen, 2013). Specifically, the authors used interdependent contingencies to reduce food waste. The strength of this study lies in its simplicity, economic affordability, and effectiveness. This study also tackles a critical issue for today’s policy makers and citizens. In fact, the European Union estimates annual food waste to be near 88 million tons at the cost of €143 billion (European Commission, 2016). Aligning our model with this study offers a simple setup and resonance among the Scandinavian people. Nevertheless, the study did not seem to generate (direct) replication procedures in other countries.

If we have ambitions of large-scale behavioral change, we should use this experiment as an illustration of how the use of macrobehaviorFootnote 1 and metacontingencies (Glenn, 2004; Glenn & Malott, 2004; Malott & Glenn, 2006) might produce additional value to nudge interventions. Macrobehaviors are defined as “the behaviors of many individuals having similar topographies that produce an effect at the level of the culture” (Glenn, 2004, in Delgado, 2012, p. 21). The paper demonstrates a win–win scenario, or a non-zero-sum game, between food suppliers and consumers, as long as the nudge remains in place. Cooperation between participants is key to the intervention’s relevance and sustainability. We submit that a metacontingency analysis might add a third beneficiary: the environment. This system selects and sustains the product of cooperation over time and endures across situations. This triangulation produces a sustainable cultural practice.

In the following section, we define nudge at a conceptual level and contextualize the term in a broader behavioral perspective by emphasizing its social value. Next, we present a summary of the two independent nudging experiments and their results. In the fourth section, we suggest a cultural framework meant to improve both current and future nudging research. Concluding, we discuss whether this and other experiments targeting societal well-being should address individual behaviors or the social architecture.

The Definition of Nudge in Behavioral Sciences

A nudge is a simple environmental change meant to influence behavior without compelling it. Developments in behavioral economics and nudge-related studies are at the height of their popularity at the conceptual and empirical levels. Expanding on the findings of behavioral economists who precede him, Richard Thaler helped to mainstream the idea of nudging. He won the most recent Nobel Prize in Economics and is the cofounding father of nudging, together with Cass R. Sunstein, the most recent Holberg laureate (2018) at the time of writing. The term nudge makes its first appearance in Thaler and Sunstein’s 2008 book Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. A nudge is a form of paternalism in its softest and most libertarian form. Embodied in the architecture of choice, Thaler proposes that a nudge “alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives” (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008, p. 6).

Various scholars have refined the definition and scope of nudging: Halpern (2015); Marchiori, De Ridder, Veltkamp, and Adriaanse (2015); Hansen (2017); and Mathis and Tor (2016) emphasize strict properties for nudges to be defined as such. Furthermore, an innovative line of nudging and other concepts derived from behavioral economics has successfully approached public policy making and governmental regulation. Scholars and policy makers alike refer to this application as behavioral insights (OECD, 2017a, p. 401).

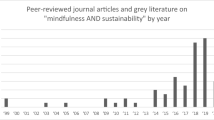

Despite the multidisciplinary research initiatives feeding the establishment and the development of nudging and behavioral insights research, the contributions of behavior analysis are extremely limited. Based on our preliminary research, very few works seem to mention nudge explicitly and contextualize the term within a behavior-analytic framework (e.g., Brandon, 2008; Rachlin, 2015). Even though descriptions of antecedent behavior-control techniques have been addressed in community settings (Luyben, 2009), we record a lack of effort from behavior analysis in joining the conceptual and experimental work on behavioral insights.

Nudging represents more than a relatively new and exciting line of experimentation. In fact, nudging techniques are already included in the behavior analyst’s tool kit and should be implemented more widely. First, nudging techniques are behavioral in their function because nudges aim at influencing a target behavior or a behavioral repertoire. Nudges are considered a display of means paternalism rather than ends paternalism (Sunstein, 2013). As such, nudges are more permissible forms of behavioral control. Second, nudging capitalizes on the influences that the natural and social environment has on behavior (Simon & Tagliabue, 2018). This may be traced back to some of Skinner’s own works on behavioral selection and modification (Skinner, 1953, 1971).

Nudges address choice behavior, which represents an elective area of experimental inquiry in behavior analysis. According to the matching law (Herrnstein, 1961), the function of a nudge is to alter the probability of a behavior by changing the delayed reinforcement conditions under which it occurs. It does not eliminate the immediate reinforcement conditions under which the alternative behavior originally occurred. The point is not to eliminate (or prohibit) unwanted behaviors but simply to make them less probable. This is in line with basic behavior-analytic research.

In other words, nudging retains free choice behavior and excludes any forced choice behavior under concurrent schedules of reinforcement. Organisms naturally prefer the former to the latter, which has been empirically demonstrated, largely with pigeons (e.g., Catania & Sagvolden, 1980; Cerutti & Catania, 1986, 1997; Rachlin & Green, 1972).

Through this study, we take an active step toward bridging the behavior-analytic and behavioral economic traditions and contributing to solving some of the “wicked problems” that call for behavioral solutions. Wicked problems describe uniquely difficult and complex emerging policy problems and are conceptualized by ten characteristics in Peters (2017): “Many of the problems that threaten the well-being of cultures are cumulative effects of this sort. Smoking, drug addiction, alcoholism and obesity are the result of practices that require a re-design of cultural-behavioral contingencies” (Delgado, 2012, p. 23).

The nudging approach serves as an appreciated assist to traditional economic incentive programs and legal regulations. With regard to social issues, nudging often yields a higher return on investment (Benartzi et al., 2017) while better serving the needs of the people (obesity, diabetes, retirement savings), governments (tax collection, school attendance), and the planet (pollution and care for the environment).

The Original Study

Kallbekken and Sælen (2013) tested the effectiveness of two nudges on food waste reduction in a major Scandinavian hotel chain from June 1 to August 15, 2012. The sample included 52 hotels, with 38 in the control group and 14 in the test group. The test group was split in two (seven hotels each), where the guests were subject to one of the following test environments:

-

1.

Smaller plate size, reduced from 24 cm to 21 cm in diameter; and

-

2.

A visual social cue emphasizing the acceptance of visiting the buffet more than once, in the form of a sign that read, “Welcome back! Again! And again! Visit our buffet many times. That’s better than taking a lot once” (Kallbekken & Sælen, 2013, p. 326).

The statistically significant (p < 0.001) results are reported in Table 1. The authors recorded a reduction in food waste of 19.5% from the plate-size nudge and 20.5% from the social-cue nudge (Kallbekken & Sælen, 2013).

In addition, the authors conducted estimates of coefficients analysis concerning the observational difference for each nudge at a statistically significant rate, taking into account guest satisfaction and food sales. These estimates quantify differences-in-differences, and they report an approximation of the financial savings and CO2 emissions in food waste for each centimeter of decrease in plate diameter. Given the purpose of this paper, we choose not to elaborate on these data and refer the reader to the original article for further specifications and results.

Data from online follow-up surveys did not show any decline in customer satisfaction, and the hotel attained economic (and environmental) cost reduction. This result may yet be paraphrased as a win–non-loss scenario, without affecting the main claim of our analysis. Based on these findings, the authors see a win–win scenario between the stakeholders of the hotel chain and the customers.

Nudging and the Redesign of Contingencies Including All Terms

In the experiment illustrated previously, nudging takes the form of intervening on the antecedents in order to promote behavior change in a forecasted way. Specifically, the intervention consists of adding two independent discriminative stimuli that enable access to the natural reinforcer of participatory commitment to making efficient use of environmental resources (namely, not wasting food).

The driver of sustainable behavior maintenance (i.e., a selected cultural practice) features the aggregate outcome of a 20% average decrease in food waste in the same way a sustaining motivating operation mediates interdependent behavioral contingencies in the degree of a customer’s environmental choices (Cesareo, 2018; Michael, 1982). The units of analysis of macrobehavior or metacontingencies consists of (a) an aggregate product (AP), resulting from (b) interlocking behavioral contingencies (IBCs) between the hotel restaurant and its guests, feeding (c) a receiving system (RS). These units shed light on the differences between a strategy for changing individual behaviors and a strategy for changing cultural practices generalized over situations and time. We illustrate and relate macrobehavior and metacontingencies to an alternative way of interpreting and upscaling this nudging experiment, and possibly others, according to a cultural selectionist model.

As long as the nudges are in place, it is clear that the behavioral output of food waste reduction should be retained. When we acknowledge the success of this intervention, one question arises: What happens when the nudges are withdrawn? Will the organization and its customers maintain the reduction in food waste, or will they revert to baseline values? To establish a cultural practice that may last, contingencies must change from mere nudging—or macrocontingencies—to metacontingencies (i.e., coordinated group behavior). The definition of a cultural practice must include the necessary condition of survival over time, even though old members of the culture are replaced by new ones (Sandaker, 2009, p. 288).

For the analysis of learning, changing, and maintaining behavior, our theoretical framework is the functional concept offered by operant conditioning. This tradition, however, is mostly concerned with individual behaviors. Sigrid Glenn (1986, 1988, 2003; Glenn et al., 2016) defines the contingencies responsible for the selection of cultural practices in terms of metacontingencies.

A metacontingency is the joint effect of interacting people (IBCs), their AP, and an RS. The IBCs are prerequisites for obtaining the AP, which could not be produced by the same individuals acting separately. The RS, the third component of the metacontingency, is responsible for the selection of the AP and hence for the selection of the cultural practice. The concept of metacontingencies is different from macrocontingencies (Abreu Vasconcelos, 2013; Glenn, 1986, 1988; Glenn & Malott, 2004; Todorov, 2013; Ulman, 1998), in the sense that the AP of many people’s behaviors may have societal impact (like paying taxes or quitting smoking), but there need not be any cooperation or IBCs. Figure 1 depicts a schematization of the main differences between a four-term behavioral contingency, a metacontingency, and a macrocontingency, as well as where we consider nudges most effective.

In some sense, the nudging approach reflects macrocontingencies that prompt many people in various forms (whether they are taxpayers or smokers, etc.) to make more sensible choices for themselves and society. However, they do so independently of each other. We may talk about an AP both in the case of large-scale individual behavior change (i.e., macrobehavior) and in the case of coordinated (meta) behavioral efforts. These two processes are different insofar as the AP cannot be produced without a coordinated effort of individuals in a metacontingency (Glenn, 1986, 1988, 2003, 2004).

The consequence of one member of the culture or organization serves as the antecedent of another member. Individuals are responsible for maintaining cultural practices, as a result of their cooperation, which is transmitted generation to generation. In the previous example, both employees and customers are necessary in order to achieve the common result. They must coordinate, as any unidirectional effort does not fulfill the requirement of interdependency in the production of APs. Moreover, restaurant guests will leave, and new customer generations will continue to attend meals. If new behaviors are established by too few individuals, the practice is likely to die out with the individuals, without being transmitted further.

This work is grounded in the increasing production of empirical studies aimed at nudging large-scale behaviors and their ambitious aims to create sustainable practices. We believe that the metacontingency’s scope may help to structure better coordinated interventions and achieve outcomes characterized by more longevity. The selectionist perspective suggests that consequences of behaviors—whether individual behavior or the behavior of a group—influence the probability of the future recurrence of behaviors.

A nudge introduces stimulus control by mainly changing the antecedents of behaviors; a metacontingency brings the behaviors under the control of a reinforcing event. The concept of metacontingency and the ongoing research on the selection of cultures offer a promising approach to understanding how cultural practices evolve, are maintained, or go extinct.

This perspective is in its infancy and will be refined and developed as best practices and experiments offer new insights. We hope to open a space for discussion of this idea to further enhance a multidisciplinary dialogue and to program green behaviors in our cultural repertoires. We aim to achieve enduring social changes in the cultural contingencies of behavior following the choice architects’ departure from the field.

The Need for a Behavior-Analytic Systems Perspective

Behavioral systems analysis is the applied branch of behavior analysis concerned with organizational behavior management in complex systems. We discuss metacontingencies in light of some founding concepts in systems analysis. They may be useful to define and analyze the role of feedback and how selection and interdependency take place.

According to general systems theory, a system possesses three interdependent and fundamental properties (Parsons, 1951; Skyttner, 2005; Von Bertalanffy, 1968). This holds true whether the system is social or not. The first property is the system’s function, which depicts its relation to the environment. Similar to the metacontingency, external feedback loops that reach outside the system comprise the relation between the AP and the RS.

The second property is the system’s process, and it maintains the system’s overall function. Parallel to the IBCs, the process of a system serves as a prerequisite for its overall functioning. The feedback from the RS (i.e., the environment) is the selecting unit for the maintenance or adjustment of the AP.

The third property is the system’s structure. The metacontingency does not deem the structure responsible for the AP and for the relation to the environment.

We depict a representation of the model in Fig. 2: It builds on the classic three-term metacontingency from Glenn and Malott (2004). The authors described metacontingencies in organizational settings, exemplified through the restaurant business: The work of interdependent colleagues (IBCs) leads to a culinary product (AP), which is received (or rejected) by a group of customers (RS).

Nonetheless, the model we put forward is different from Glenn and Malott’s model in at least two regards. The first difference is the inclusion of both employees’ and customers’ IBCs in the first term because the AP (reduced food waste) may only be achieved as the result of their cooperation. The second difference postulates that the RS is comprised of both an internal selector (e.g., business stakeholders) and an external selector (e.g., overarching policies), which feed back to the IBCs (i.e., maintain cooperation).

Scholars adopting a selection-of-cultures, or cultural selection perspective, are further refining the conceptual framework of the third level of selection described by Skinner (1981). The object of debate concerns the unit of selection and whether it is the IBCs or the resulting AP that is selected by the RS (e.g., Carvalho Couto & Sandaker, 2016; Couto de Carvalho & Sandaker, 2016; Houmanfar, Rodrigues, & Ward, 2010; Krispin, 2016).

If the answer were straightforward, we would be in the position to build a nudge catalogue that may be applicable with the same degree of efficacy across different cultures and organizations. Contrarily, nudges are not considered “silver bullets.” Their effectiveness seems to rely on social and cultural context. Contributions from behavior analysis and, specifically, its efforts in inducting universal laws of behavior from empirical work may overcome any variability in results by identifying the behavioral contingencies behind cross-cultural nudge studies.

Depending on the researcher’s scope of analysis, nudging interventions must remain flexible to meet the degree of interdependence between the contributors of the AP. A metacontingency analysis can help evaluate the durable effects of nudging on a large scale and contribute to better understanding and predicting large-scale behavior.

In addition to the benefits that a cultural level of analysis bears, the increase in complexity and terms also leads to some discussions that need be addressed. First, metacontingency analyses are by definition group level. The term culturant (Glenn et al., 2016) refers to phenomena that capture the selection of interaction between two or more people: “The contingent relation, then, in a metacontingency is between a culturant (IBC + AP) and its selecting consequences” (p. 13).

The culturant is the counterpart of the operant behavior that comprises the unit of analysis at the individual level. It captures the role of the antecedents on learning with high technical precision. Interpreting the effects of nudging interventions through operant conditioning may comprise a satisfactory level of explanation as the data may be aggregated. Metacontingencies are able to capture the interactions and identify the IBCs. We need not refer to them in order to explain individual behavior. The control of behavior exerted by antecedents is therefore only more vulnerable to the changing contingencies, whereas the cooperation resulting from the IBCs strengthens the contingencies and makes the behavior more likely to occur.

There is no nudging study that claims its effectiveness based on single-case design. The exposure of a single individual to an effective nudge may have a cumulative impact on group change and may initiate the evolution of cultural practices through continuous exposure and learning. Without the component of interaction, the appropriate term for cumulative group behavioral contingencies would be macrocontingencies, which are not characterized by interlocks between the consequences of one and the antecedents of the other. The concept may still be useful, but our interpretations become less complex—and perhaps less desirable—if we leave the interaction out of the analysis.

This limitation in applicability is the primary strength of a metacontingency analysis, which provides thorough functional explanations of interdependent behavior. By extension, the reader might argue that any study of group behavior might be improved by a metacontingency analysis. The aim of such analysis would possibly consist of identifying the environmental contingencies that sustain the interaction between “nudgers” and those being nudged to maintain the positive outcomes of the intervention. We must therefore differentiate between cumulative behavior and the result of coordinated and cooperative behavior. We suggest introducing a metacontingency analysis only to the studies concerned with the latter.

Second, engaging in a system analysis can mean adding further (and unnecessary) complexity to the understanding of nudging and sustainable behavior. Research efforts are more demanding both in the behavioral-mapping phase preceding the intervention and while fragmenting the aggregate data after the experiment. For example, some of the most effective nudging interventions tackle individual choice behavior through default rules setting, as in the case of voluntarily registering as an organ donor in opt-in countries versus opt-out countries (Johnson & Goldstein, 2003). An analysis of the individual contingencies of reinforcement may suffice for interpreting the cumulative incidence of this instance of prosocial behavior.

Third, the design of metacontingencies may not be adaptable enough to fit the heterogeneity of applied settings, as there are issues of retaining a strict degree of experimental control. For example, it is unclear from the original study whether the experimenters involved the staff of the hotel restaurant directly or whether they interacted with the management only in order to swap the plates and post the signage.

Last, we address the permissibility to programming positive consequences (or the threat of negative consequences) to reinforce nudged behavioral and cultural repertoires. In fact, introducing reinforcing consequences in order to sustain the effectiveness of the redesigned antecedents does not fit the scope of nudging. Nudges need not substantially change the (economic) incentives of alternative choice behavior (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008) but rather represent “means of bringing behavior under the control of wide and abstract reinforcer contingencies” (Rachlin, 2015, p. 198).

In a subsequent paper, Cass Sunstein (2017) suggests this strategy in order to overcome the limits of nudges when they do not seem to work. We argue that providing positive consequences for the behaviors exposed to nudges that already work would make them even more effective. In our example on food waste, this may mean rewarding cooperative behavior. Yet, as this manipulation programs changes in consequences that alter the incentive system, the issue deserves further clarifications through forthcoming studies.

Conclusions

The nudging experiment chosen to illustrate the model of cultural selection we put forward represents one example of designing a sustainable social architecture. Our analysis may be suitable for any other nudging study, in which the desired outcome is dependent on the interconnection of individual behavioral contingencies.

Specifically, we suggest capitalizing on the degree of cooperation between supplier–consumer groups in order to consolidate the acquisition of more functional and interdependent behavioral repertoires. Addressing these relationships through the metacontingency concept is a way to strengthen the sustainability of nudging interventions by embedding them into cultural practices. It not only contributes to common, farsighted environmental goals but also may have applications for health and welfare, shared economies, and social equality issues. The manipulation of contingencies to reduce food waste did not negatively affect the customers’ meal experience and may therefore have implications for a sustainable cultural practice. We stand to analyze choice behaviors by enhancing the effect of antecedent control with the effect of the selecting agent.

Although nudging represents a powerful and noninvasive approach to changing individual human choice behaviors, the conceptual framework offered by a behavior-analytic approach may inform the creation of more cooperative cultural practices. Showing environmentally responsible behavior is an obligation we have toward the well-being of our planet and its limited resources. Sustainable solutions cannot be handled on an individual basis; they need be embedded in our social and cultural systems.

References

Abreu Vasconcelos, L. (2013). Exploring macrocontingencies and metacontingencies: Experimental and non-experimental contributions. Suma Psicológica, 20(1), 31–43 Retrieved from http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0121-43812013000100003&nrm=iso.

Alavosius, M., Getting, J., Dagen, J., Newsome, W., & Hopkins, B. (2009). Use of a cooperative to interlock contingencies and balance the commonwealth. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 29(2), 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/01608060902874575.

Benartzi, S., Beshears, J., Milkman, K. L., Sunstein, C. R., Thaler, R. H., Shankar, M., et al. (2017). Should governments invest more in nudging? Psychological Science, 28(8), 1041–1055. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617702501.

Biglan, A. (2015). The nurture effect: How the science of human behavior can improve our lives and our world. Oakland: New Harbinger.

Bohnet, I., van Geen, A., & Bazerman, M. (2016). When performance trumps gender bias: Joint vs. separate evaluation. Management Science, 62(5), 1225–1234. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2015.2186.

Brandon, P. (2008). BEHAVIORAL behavioral economics [Review of the book Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness, by R. H. Thaler & C. R. Sunstein]. Retrieved from https://www.amazon.com/review/R3FC6CUFXEZTWC.

Carvalho Couto, K., & Sandaker, I. (2016). Natural, behavioral and cultural selection-analysis: An integrative approach. Behavior and Social Issues, 25, 54–60. https://doi.org/10.5210/bsi.v25i0.6891.

Catania, A. C., & Sagvolden, T. (1980). Preference for free choice over forced choice in pigeons. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 34(1), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1980.34-77.

Cerutti, D., & Catania, A. C. (1986). Rapid determinations of preference in multiple concurrent-chain schedules. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 46(2), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1986.46-211.

Cerutti, D., & Catania, A. C. (1997). Pigeons’ preference for free choice: Number of keys versus key area. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 68(3), 349–356. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1997.68-349.

Cesareo, M. (2018). Behavioral economics and behavioral change policies: Theoretical foundations and practical applications to promote well-being in the Italian context (Unpublished doctoral thesis, International University of Language and Media, Milan, Italy).

Couto de Carvalho, L., & Sandaker, I. (2016). Interlocking behavior and cultural selection. Norsk Tidsskrift for Atferdsanalyse, 43(1), 19–25 Retrieved from www.nta.atferd.no/loadfile.aspx?IdFile=1376.

Delgado, D. (2012). The selection metaphor: The concepts of metacontingencies and macrocontingencies revisited. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 44(1), 13–24. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rlps/v44n1/v44n1a02.pdf.

European Commission. (2014). Taking consumer rights into the digital age: Over 507 million citizens will benefit as of today [Press release]. Retrieved from http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-14-655_en.htm.

European Commission. (2016). Food waste [Press release]. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/food/safety/food_waste_en.

Geller, E. S. (1989). Applied behavior analysis and social marketing: An integration for environmental preservation. Journal of Social Issues, 45(1), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1989.tb01531.x.

Glenn, S. S. (1986). Metacontingencies in Walden two. Behavior Analysis & Social Action, 5(1–2), 2–8. Retrieved from https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/basa/article/view/7345/5861.

Glenn, S. S. (1988). Contingencies and metacontingencies: Toward a synthesis of behavior analysis and cultural materialism. The Behavior Analyst, 11(2), 161–179. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22478011.

Glenn, S. S. (2003). Operant contingencies and the origin of cultures. In K. A. Lattal & P. N. Chase (Eds.), Behavior theory and philosophy (pp. 223–242). Boston: Springer.

Glenn, S. S. (2004). Individual behavior, culture, and social change. The Behavior Analyst, 27(2), 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03393175.

Glenn, S. S., & Malott, M. E. (2004). Complexity and selection: Implications for organizational change. Behavior and Social Issues, 13(2), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.5210/bsi.v13i2.378.

Glenn, S. S., Malott, M. E., Andery, M. A. P. A., Benvenuti, M., Houmanfar, R. A., Sandaker, I., & Vasconcelos, L. A. (2016). Toward consistent terminology in a behaviorist approach to cultural analysis. Behavior and Social Issues, 25, 11–27. https://doi.org/10.5210/bsi.v.25i0.6634.

Halpern, D. (2015). Inside the nudge unit: How small changes can make a big difference. London: WH Allen.

Hansen, P. G. (2017). The definition of nudge and libertarian paternalism: Does the hand fit the glove? European Journal of Risk Regulation, 7(1), 155–174. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1867299x00005468.

Herrnstein, R. J. (1961). Relative and absolute strength of response as a function of frequency of reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 4(3), 267–272. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1961.4-267.

Houmanfar, R. A., Rodrigues, N. J., & Ward, T. A. (2010). Emergence and metacontingency: Points of contact and departure. Behavior and Social Issues, 19, 78–103. https://doi.org/10.5210/bsi.v19i0.3065.

Johnson, E. J., & Goldstein, D. (2003). Do defaults save lives? Science, 302(5649), 1338–1339. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1091721.

Kallbekken, S., & Sælen, H. (2013). “Nudging” hotel guests to reduce food waste as a win–win environmental measure. Economics Letters, 119(3), 325–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2013.03.019.

Keller, J. J. (1991). The recycling solution: How I increased recycling on Dilworth Road. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 24(4), 617–619. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1991.24-617.

Krispin, J. (2016). What is the metacontingency? Deconstructing claims of emergence and cultural-level selection. Behavior and Social Issues, 25, 28–41. https://doi.org/10.5210/bsi.v25i0.6186.

Luyben, P. D. (2009). Applied behavior analysis: Understanding and changing behavior in the community—a representative review. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 37(3), 230–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852350902975884.

Malott, M. E., & Glenn, S. S. (2006). Targets of intervention in cultural and behavioral change. Behavior and Social Issues, 15(1), 31–56. https://doi.org/10.5210/bsi.v15i1.344.

Marchiori, D., De Ridder, D., Veltkamp, M., & Adriaanse, M. (2015). What is in a nudge: Putting the psychology back in nudges. European Health Psychologist, 17, 546. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12297.

Mathis, K., & Tor, A. (2016). Nudging: Possibilities, limitations and applications in European law and economics. Cham: Springer International.

Michael, J. (1982). Distinguishing between discriminative and motivational functions of stimuli. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 37(1), 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1982.37-149.

Obama, B. H. (2006). The audacity of hope: Thoughts on reclaiming the American dream. New York: Crown River Press.

Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development. (2017a). Behavioural insights and public policy: Lessons from around the world. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development. (2017b). Behavioural insights in public policy: Key messages and summary from OECD international events, May 2017. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/OECD-events-behavioural-insights-summary-may-2017.pdf.

Parsons, T. (1951). The social system. London: Routledge.

Peters, B. G. (2017). What is so wicked about wicked problems? A conceptual analysis and a research program. Policy and Society, 36(3), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2017.1361633.

Rachlin, H. (2015). Choice architecture: A review of Why nudge: The politics of libertarian paternalism. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 104(2), 198–203. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeab.163.

Rachlin, H., & Green, L. (1972). Commitment, choice and self-control. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 17(1), 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1972.17-15.

Sandaker, I. (2009). A selectionist perspective on systemic and behavioral change in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 29(3–4), 276–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/01608060903092128.

Simon, C., & Tagliabue, M. (2018). Feeding the behavioral revolution: Contributions of behavior analysis to nudging and vice versa. Journal of Behavioral Economics for Policy, 2(1), 91–97 Retrieved from http://sabeconomics.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/JBEP-2-1-13.pdf.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. New York: Free Press.

Skinner, B. F. (1971). Beyond freedom and dignity. New York: Knopf/Random House.

Skinner, B. F. (1981). Selection by consequences. Science, 213(4507), 501–504. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7244649.

Skyttner, L. (2005). General systems theory: Problems, perspectives, practice (2nd ed.). Hackensack: World Scientific.

Sunstein, C. R. (2013). Simpler: The future of government. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Sunstein, C. R. (2014). Nudging: A very short guide. Journal of Consumer Policy, 37(4), 583–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-014-9273-1.

Sunstein, C. R. (2016). People prefer System 2 nudges (kind of). Duke Law Journal, 66, 121–168. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2731868.

Sunstein, C. R. (2017). Nudges that fail. Behavioural Public Policy, 1(1), 4–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2016.3.

Sunstein, C. R., Reisch, L. A., & Rauber, J. (2017). Behavioral insights all over the world? Public attitudes toward nudging in a multi-country study (Harvard John M. Olin Discussion Paper No. 916). SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2921217.

Tagliabue, M., Sandaker, I., & Ree, G. (2017). The value of contingencies and schedules of reinforcement: Fundamentals of behavior analysis contributing to the efficacy of behavioral business research. Journal of Behavioral Economics for Policy, 1, 33–39 Retrieved from http://www.sabeconomics.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/JBEP-1-S-7.pdf.

Thaler, R. H. (2018). Nudge, not sludge. Science, 361(6401), 431–431. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau9241.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Todorov, J. C. (2013). Conservation and transformation of cultural practices through contingencies and metacontingencies. Behavior and Social Issues, 22, 64–73. https://doi.org/10.5210/bsi.v22i0.4812.

Ulman, J. D. (1998). Toward a more complete science of human behavior: Behaviorology plus institutional economics. Behavior and Social Issues, 8(2), 195. https://doi.org/10.5210/bsi.v8i2.329.

Von Bertalanffy, L. (1968). General system theory: Foundations, development, applications. New York: G. Braziller.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Nicholas J. Bergin and Gunnar Ree; this work would not have been complete without their dedication. The authors would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Funding

This work has been financially supported by OsloMet - Oslo Metropolitan University (earlier Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Copyright Information

The use and reprint of Table 1 is authorized by the original publisher (Elsevier) with license number 4003061329299.

Conflict of Interest

The contents of this manuscript were first presented at the Eighth Conference of the European Association for Behaviour Analysis, hosted in Enna, Italy, on September 16, 2016. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tagliabue, M., Sandaker, I. Societal Well-Being: Embedding Nudges in Sustainable Cultural Practices. Behav. Soc. Iss. 28, 99–113 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42822-019-0002-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42822-019-0002-x