Abstract

Iron oxide nanoparticles are available in two common phases, namely magnetite (Fe3O4) and maghemite (Fe2O3). Upon exposure to oxygen atoms, the magnetite phase readily oxidizes into the maghemite phase with the partial conversion of ferrous ions into ferric ions. We report on the approach to determine the ratio of magnetite and maghemite in iron oxide nanoparticles synthesized by the wet chemical route. X-ray diffraction studies and transmission electron microscopy observations confirmed the formation of highly crystalline nanoparticles of size \(\left( {7 \pm 2} \right)\) nm. The average particle size is in the magnetic single-domain range suitable for the superparamagnetic behavior. The Mössbauer spectrum of the sample is composed of two six-line patterns in perfect agreement with the theoretically predicted model. The extracted Mössbauer parameters show contribution of two phases accounting for 47% magnetite and 53% maghemite. The hysteresis loops of the iron nanoparticles demonstrated the “S-shaped” pattern with negligible coercivity and remanence magnetization. This result reveals a promising method to synthesize and characterize magnetic nanoparticles of uniform size with a potential for biomedical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Commonly available oxides of iron, especially magnetite (Fe3O4) and maghemite (γ-Fe2O3), have been studied for a long time because of their beneficial magnetic properties [1,2,3]. Iron oxide nanoparticles exhibit significantly different magnetic properties when compared to their bulk counterparts, and they are also biodegradable, nontoxic, and benign [4, 5]. Consequently, magnetic nanoparticles are used for biological applications in targeted drug delivery, magnetic resonance imaging, and cancer therapy hyperthermia [6,7,8,9,10,11]. As one of the most important materials, these magnetic nanoparticles are also used in lithium ion batteries, ferrofluids, sensors, magnetic storage, magnetic inks, water treatment, and other applications [12,13,14,15,16,17].

Magnetite has the face-centered cubic spinel crystal structure with iron cations in two valence states, Fe2+ and Fe3+ [9]. All of the tetrahedral sites are exclusively occupied by Fe3+ ions while the octahedral sites are evenly filled by Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions. The tetrahedral and octahedral sites are often referred as A-sites and B-sites, respectively [18]. In stoichiometric magnetite, the ratio of Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions is 1:2. The magnetite phase oxidizes into the maghemite phase by natural weathering or other processes with the conversion of all Fe2+ ions into Fe3+ ions. The oxidation process results in iron vacancies in the crystal lattice due to the partial removal of iron to compensate for the positive charges. Both magnetite and maghemite demonstrate ferrimagnetic properties at room temperature, and it is difficult to distinguish between the two oxides on the basis of their magnetic properties [2]. However, nanoparticles of magnetic materials exhibit size-dependent magnetic properties and behave differently at reduced dimensions [19]. Bulk magnetite is a multidomain ferrimagnet with a Curie temperature of 585 °C, while magnetite nanoparticles smaller than 100 nm consist of single-domain magnetic structure. Magnetic nanoparticles with size smaller than ~ 20 nm show superparamagnetic properties where the magnetization of nanoparticles is randomized by thermal energy.

For biomedical and other technological applications, iron oxide nanoparticles should have high magnetization values and narrow particle size distribution [8]. The most common approach for the production of magnetite nanoparticles is chemical coprecipitation of iron salts in which nanoparticles are synthesized in two stages: initial nucleation from the supersaturated solution and the subsequent crystal growth [20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Stoichiometric mixture of ferrous and ferric salts is reduced in an alkaline medium in inert environment for the formation of magnetite. The chemical reaction involved in the formation of magnetite is as follows:

In a non-oxidizing alkaline medium, complete precipitation of Fe3O4 can be achieved. However, magnetite readily transfers into maghemite upon oxidation by the ion transfer process:

The research on iron oxide nanoparticles is focused on controlling the size, morphology, and composition in order to improve their specific properties. Kovalenko et al. [27] have synthesized cubic and spherical Fe3O4 nanocrystals from thermal decomposition of iron oleate precursors. Liu et al. [28] synthesized single-crystalline Fe3O4 nanotubes to study the electrical transport properties at reduced dimensions. Jia et al. [29] described an approach to convert haematite (α-Fe2O3) nanorings into Fe3O4 or γ-Fe2O3 by oxidation–reduction or reduction–oxidation process. Partial oxidation of magnetite results in variable ratio of \({\text{Fe}}^{2 + }\) and \({\text{Fe}}^{3 + }\) in the magnetic nanoparticles which cannot be distinguished easily using standard X-ray diffraction (XRD) techniques since the crystal structure of both of these oxides is very similar [30]. In this paper, we report on a simple procedure to synthesize iron oxide nanoparticles of uniform size distribution using a hydrothermal process without using any additional surfactants or surface modifications. This novel approach enables the synthesis of magnetic nanoparticles from the complete dissociation of iron salts at relatively low temperature. We analyzed as-synthesized nanoparticles and determined the ratio of \({\text{Fe}}^{2 + }\) and \({\text{Fe}}^{3 + }\) using Mössbauer spectroscopy. Synthesis of nanoparticles without additional toxic chemical resulted in the production of biocompatible nanoparticles which can find applications in targeted drug delivery or as contrast-enhancing elements for biomedical diagnostic application.

2 Experimental methods

Analytical-grade chemical reagents including ferrous chloride tetrahydrate (FeCl2·4H2O), ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O), hydrochloric acid (HCl) and tetramethylammonium hydroxide (N(CH3)4OH, 25%) were used for material synthesis. Deionized water degassed with argon gas for half an hour was used to prepare 2 M HCl solutions. In a typical procedure, a 1:2 ratio of Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions was achieved by mixing 2.5 mL of a 2 M FeCl2 solution with 10 ml of FeCl3 solution at room temperature. The mixture was vigorously stirred, and 21 mL of aqueous tetramethylammonium hydroxide solution was slowly added to it. The solution color changed from orange to black with the immediate precipitation of iron oxide nanoparticles. The resulting mixture was then transferred into a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave and heated at 180 °C for 24 h. After heat treatment, the furnace was allowed to cool naturally to room temperature to obtain iron oxide nanoparticles in the powder form.

XRD data were collected at room temperature using a Rigaku MiniFlex equipped with copper Kα (0.154 nm) radiation source. The surface morphology of the particles was observed by transmission electron microscope (TEM) and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) was used to get information about the elemental distributions. The TEM, HRTEM, and scanning TEM-EDS observations were performed on a Tecnai Osiris TEM/STEM operating at 200 kV equipped with a SuperX™ quad EDS detection system. Samples were prepared by suspending a small portion of the powder in isopropanol followed by brief sonication in an ultrasonicator. A small drop of the solution was then placed onto a lacey carbon TEM support film (Ted Pella no. 1895), and the excess solvent was wicked away. The STEM-EDS maps were collected using Bruker Esprit software version 1.9 with a sub-nanometer probe having ~ 0.8 nA of beam current. The size of the particles observed in TEM images was measured using ImageJ software. Vibrating sample magnetization (VSM) measurements were carried out using a vector magnetometer model 10 VSM system (MicroSense Co.) equipped with a 30 kOe electromagnet. During the hysteresis measurement, the applied magnetic field was increased to the maximum field of 15 kOe at room temperature in steps of 5 Oe. The phase of a powder iron oxide nanoparticle sample was investigated by 57Fe in an Rh matrix Mössbauer spectroscopy. The measurement was performed using a MS4 spectrometer operating in the constant acceleration mode in transmission geometry. The measurement was performed at room temperature. A 50 mCi 57Co in Rh held at room temperature was used as source. The obtained spectrum was least square fitted to determine the oxidation states of Fe species.

3 Results and discussion

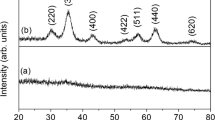

3.1 X-ray diffraction studies

Figure 1 shows the XRD pattern of iron oxide nanoparticles synthesized using the hydrothermal method. X-ray diffraction indicates the formation of monocrystalline iron oxide nanoparticles with prominent peaks from (111), (220), (311), (222), (400), (422), (511), and (440) planes. The sharp peaks of nanoparticles demonstrate the good crystallinity of as-synthesized nanoparticles. It should be noted that peaks with intensities below the dotted line can be ignored as they represent the background noise of the measurement. The presence of Fe3O4 and γ-Fe2O3 cannot be distinguished from XRD as magnetite and maghemite have nearly identical crystal structures [30]. The XRD pattern also contains a sharp peak at an angle of 23° from FeCl3 crystals. Such an impurity peak is expected in our sample because we have not washed our nanoparticles with deionized water after the synthesis. However, further TEM observation does not show any features of impurity phases, and we can conclude that the hydrothermal process results in the reduction of iron chloride salts into iron oxide nanoparticles.

3.2 Transmission electron microscopy

Figure 2 shows TEM images of iron oxide nanoparticles at low (a) and high (b) magnification. The hydrothermal procedure resulted in the formation of regularly shaped nanoparticles with uniform size distribution. The high-resolution TEM image clearly shows the crystal lattice of these nanoparticles, confirming their high crystallinity. The atomic planes in these nanoparticles are well-ordered and lack any lattice defects, such as dislocations and stacking faults. We have measured the lattice spacing of several particles labeled A, B, C, and D in Fig. 2b. The lattice fringes with spacings of 0.2891, 0.4923, 0.2374, and 0.2515 nm can be assigned to (220), (111), (222), and (311) planes of iron oxide, respectively, which is in agreement with the XRD pattern discussed earlier. The encircled (yellow color) region in Fig. 2b is zoomed in and presented in inset with the scale bar of 10 nm. The higher magnification view indicates nanoparticles with lattice fringes measuring 0.2891, 0.4923 nm which corresponds to (220) and (111) planes.

a Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of iron oxide nanoparticles. b High-resolution TEM images showing lattice spacing of individual nanoparticles. The inset shows magnified image consisting of two particles, labeled A and B, with interplanar spacing corresponding to (220) planes and (111) planes. c Histogram of the particle size distribution of 200 nanoparticles measured using ImageJ software

Figure 2c shows a histogram of the particle size distribution of iron oxide nanoparticles obtained from TEM images measured from 200 particles. The nanoparticles show a narrow particle size distribution with average size of \(\left( {7 \pm 2} \right)\) nm. The current high-yielding synthetic method can be easily scaled up. For example, 4.2 g of nanoparticles could be obtained from a single batch reaction using 10 ml of iron chloride solution. EDS analysis (Fig. 3a) clearly indicates the presence of elements such as iron and oxygen in the material and confirms the purity of the prepared nanoparticles. Additional contributions from copper, carbon, and silicon are from the TEM grid used during imaging. In addition to the aggregation of particles observed in TEM images, the qualitative elemental maps illustrate the distribution of these elements across the specimen. Figure 3b, c shows the homogeneous spread, at a nanometer scale, of iron and oxygen throughout the sample.

3.3 Magnetization measurement

The graph of magnetization of the sample at several applied magnetic fields for iron oxide nanoparticles is presented in Fig. 4. Hysteresis measurements conducted at different increments of the applied field, to ensure reliability of the obtained results, do not show significant deviation from each other. Magnetization loops exhibit an “S-shaped” pattern with almost zero coercivity and negligible remanence values. The magnetization of the sample saturated quickly to 27 emu/g when the applied magnetic field was increased above 3 kOe. This saturation magnetization (Ms) value is considerably smaller than that of bulk iron (Ms = 222 emu/g) which is consistent with earlier reports [27, 31, 32]. The value of saturation magnetization decreases when particles are reduced in size because of several factors. Primarily, the saturation magnetization for particles below 10 nm in size is lowered because of the spin canting effect. However, these single-domain magnetic nanoparticles are ideal for superparamagnetic behavior at room temperature.

3.4 Mössbauer spectroscopy

Mössbauer spectroscopy provides the quantitative information on the oxidation state of Fe species, and it is a powerful tool to determine the contribution of Fe ions arising from A- and B-sites in a sample. The Mössbauer spectrum for the sample, depicted in Fig. 5, was least square fitted to extract hyperfine parameters, centroid shifts (δ), quadrupole shift (ε), magnetic hyperfine field (Bhf), Lorentzian linewidth (Γ), and intensities (I). All δ-values are given with respect to metallic α-iron at room temperature. The Mössbauer spectrum for the sample consists of two six-line patterns with relatively narrow lines and can be accurately fitted with two sextets. The outer sextet is attributed to Fe3+ on A-sites of magnetite, while the inner sextet is attributed to iron atoms located on B-sites of spinel structure. However, a detailed inspection reveals that the spectrum is best fitted with three sub-spectra. The first sub-spectrum exhibits the δ value of 0.315 mm/s and Bhf of 49.5 T, which are characteristic values for Fe+3 in tetrahedral environment in magnetite. This component has an intensity of 18%. The second component has the δ value of 0.656 mm/s and Bhf of 45.6 T, which are characteristic values for Fe+2.5 in an octahedral environment. This component has an intensity of 29%. The third sub-spectrum has the δ value of 0.303 mm/s and Bhf of 49.1 T with an intensity of 53%. The intensity ratio of the first two sub-spectra is close to 1:2. This is in accordance with the intensity ratio in magnetite. The third component is a signal for Fe+3 in high-spin state, which can be attributed to maghemite, γ-Fe2O3. The slightly different hyperfine values and intensity of the first sub-spectrum compared to the A-site in magnetite are due to strong overlapping of this sub-spectrum with the third component, which is attributed to maghemite. We can hence conclude that the studied sample consists of two phases: 47% magnetite from the sum of intensities of A- and B-sites and 53% maghemite. The results show that Fe3+ ions uniformly converted to Fe2+ ion during the nucleation stages. Similar results were reported by Kolen’ko et al. [33] for ligand-capped magnetite. Costa et al. [34] have reported that if a sample contains both magnetite and maghemite, its Mössbauer spectra should be fitted by four Zeeman sextets. Two sextets correspond to Fe3+ A-site of magnetite and maghemite: One sextet is related to Fe with intermediate valence (Fe2.5+) in magnetite in B-site, and one more sextet is associated with the Fe3+ in maghemite B-site. Our attempt to lock down the parameters to the reported literature values resulted into hyperfine parameters which are not physically acceptable for magnetite and maghemite. On a similar note, the fitting attempt without locking the parameters resulted in an incorrect intensity distribution and was discarded. Hence, we believe that the Mössbauer spectra for this sample are best described by three Zeeman spectra. This allows for an unconstrained variation in the parameters, resulting in the correct intensity distribution over the physically accepted values of hyperfine constants. The Mössbauer spectra of magnetic nanoparticles could be successfully interpreted as a mixture of magnetite and maghemite, rather than nonstoichiometric magnetite which is in agreement with previous reports [35, 36]. It is worth mentioning that although Mössbauer spectroscopy shows superparamagnetic features for nanoparticles below 10 nm, our spectrum is completely magnetically blocked at room temperature because of the coupling of magnetic moments of individual nanoparticles [37]. The extracted Mössbauer parameters for the sample are summarized in Table 1.

The centroid shift (δ), magnetic hyperfine field (Bhf), quadrupole shift (ε), Lorentzian linewidth (Γ), and intensity (I) are extracted from room-temperature Mössbauer spectra analysis. The estimated errors associated with these parameters are ± 3% in I, ± 0.005 mm/s in δ and ε, ± 0.02 mm/s in Γ, and ± 0.5 T in Bhf.

4 Conclusions

In summary, we have analyzed the structural and magnetic properties to determine the contributions from magnetite and maghemite in iron oxide nanoparticles. X-ray diffraction and high-resolution TEM imaging enabled us to determine the crystallinity, particle size, and lattice parameter of the nanoparticles. The magnetic moment saturated at 27 emu/g at the applied magnetic field of 3 kOe. The nanoparticles demonstrated the single-domain magnetic properties with near-zero coercivity and negligible remanence magnetic field. Mössbauer spectroscopy showed that the sample is equally divided into magnetite and maghemite phases. The understanding of the composition of magnetite and maghemite in iron oxide nanoparticles is necessary to isolate particles with desired magnetic properties for biomedical or nanotechnological applications.

References

Tanimoto A, Kuribayashi S (2006) Application of superparamagnetic iron oxide to imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Radiol 58:200–216

Ling D, Lee N, Hyeon T (2015) Chemical synthesis and assembly of uniformly sized iron oxide nanoparticles for medical applications. Acc Chem Res 48:1276–1285

Gorski CA, Scherer MM (2010) Determination of nanoparticulate magnetite stoichiometry by Mossbauer spectroscopy, acidic dissolution, and powder X-ray diffraction: a critical review. Am Mineral 95:1017–1026

Roca AG, Marco JF, Morales MDP, Serna CJ (2007) Effect of nature and particle size on properties of uniform magnetite and maghemite nanoparticles. J Phys Chem C 111:18577–18584

Qiang Y, Antony J, Sharma A, Nutting J, Sikes D, Meyer D (2006) Iron/iron oxide core-shell nanoclusters for biomedical applications. J Nanoparticle Res 8:489–496

Laurent S, Forge D, Port M, Roch A, Robic C, Vander Elst L, Muller RN (2008) Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: synthesis, stabilization, vectorization, physicochemical characterizations, and biological applications. Chem Rev 108:2064–2110

Santoyo Salazar J, Perez L, de Abril O, Truong Phuoc L, Ihiawakrim D, Vazquez M, Greneche J-M, Begin-Colin S, Pourroy G (2011) Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in 10–40 nm range: composition in terms of magnetite/maghemite ratio and effect on the magnetic properties. Chem Mater 23:1379–1386

Kim BH, Lee N, Kim H, An K, Park YI, Choi Y, Shin K, Lee Y, Kwon SG, Na HB et al (2011) Large-scale synthesis of uniform and extremely small-sized iron oxide nanoparticles for high-resolution T 1 magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. J Am Chem Soc 133:12624–12631

Widdrat M, Kumari M, Tompa É, Pósfai M, Hirt AM, Faivre D (2014) Keeping nanoparticles fully functional: long-term storage and alteration of magnetite. ChemPlusChem 79:1225–1233

Cabrera D, Camarero J, Ortega D, Teran FJ (2015) Influence of the aggregation, concentration, and viscosity on the nanomagnetism of iron oxide nanoparticle colloids for magnetic hyperthermia. J Nanoparticle Res 17(121):1–6

Di Corato R, Aloisi A, Rella S, Greneche J-M, Pugliese G, Pellegrino T, Malitesta C, Rinaldi R (2018) Maghemite nanoparticles with enhanced magnetic properties: one-pot preparation and ultrastable dextran shell. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 10:20271–20280

Jiang F, Zhao S, Guo J, Su Q, Zhang J, Du G (2015) Fe3O4 nanoparticles-wrapped carbon nanofibers as high-performance anode for lithium-ion battery. J Nanoparticle Res 17(348):1–9

Wu W, Wu Z, Yu T, Jiang C, Kim W-S (2015) Recent progress on magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: synthesis, surface functional strategies and biomedical applications. Sci Technol Adv Mater 16(023501):1–43

Casula MF, Floris P, Innocenti C, Lascialfari A, Marinone M, Corti M, Sperling RA, Parak WJ, Sangregorio C (2010) Magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents based on iron oxide superparamagnetic ferrofluids. Chem Mater 22:1739–1748

Suri K, Annapoorni S, Sarkar AK, Tandon RP (2002) Gas and humidity sensors based on iron oxide–polypyrrole nanocomposites. Sens Actuators B Chem 81:277–282

Teja AS, Koh P-Y (2009) Synthesis, properties, and applications of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Prog Cryst Growth Charact Mater 55:22–45

Dhara S, Rastogi AC, Das BK (1993) Direct deposition of highly coercive gamma iron oxide thin films for magnetic recording. J Appl Phys 74:7019–7021

Wright JP, Attfield JP, Radaelli PG (2001) Long range charge ordering in magnetite below the Verwey transition. Phys Rev Lett 87(266401):1–4

Iacovita C, Florea A, Dudric R, Pall E, Moldovan A, Tetean R, Stiufiuc R, Lucaciu C (2016) Small versus large iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles: hyperthermia and cell uptake properties. Molecules 21(1357):1–23

Daou TJ, Pourroy G, Bégin-Colin S, Grenèche JM, Ulhaq-Bouillet C, Legaré P, Bernhardt P, Leuvrey C, Rogez G (2006) Hydrothermal synthesis of monodisperse magnetite nanoparticles. Chem Mater 18:4399–4404

Albornoz C, Jacobo SE (2006) Preparation of a biocompatible magnetic film from an aqueous ferrofluid. J Magn Magn Mater 305:12–15

Hee Kim E, Sook Lee H, Kook Kwak B, Kim B-K (2005) Synthesis of ferrofluid with magnetic nanoparticles by sonochemical method for MRI contrast agent. J Magn Magn Mater 289:328–330

Chin AB, Yaacob II (2007) Synthesis and characterization of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles via w/o microemulsion and Massart’s procedure. J Mater Process Technol 191:235–237

Wan J, Chen X, Wang Z, Yang X, Qian Y (2005) A soft-template-assisted hydrothermal approach to single-crystal Fe3O4 nanorods. J Cryst Growth 276:571–576

Salazar-Alvarez G, Muhammed M, Zagorodni AA (2006) Novel flow injection synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles with narrow size distribution. Chem Eng Sci 61:4625–4633

Basak S, Chen D-R, Biswas P (2007) Electrospray of ionic precursor solutions to synthesize iron oxide nanoparticles: modified scaling law. Chem Eng Sci 62:1263–1268

Kovalenko MV, Bodnarchuk MI, Lechner RT, Hesser G, Schäffler F, Heiss W (2007) Fatty acid salts as stabilizers in size- and shape-controlled nanocrystal synthesis: the case of inverse spinel iron oxide. J Am Chem Soc 129:6352–6353

Liu Z, Zhang D, Han S, Li C, Lei B, Lu W, Fang J, Zhou C (2005) Single crystalline magnetite nanotubes. J Am Chem Soc 127:6–7

Jia C-J, Han X-D, Heyderman LJ, Yan Z-G, Yan C-H, Zheng K, Zhang Z, Takano M, Hayashi N, Eltschka M et al (2008) Large-scale synthesis of single-crystalline iron oxide magnetic nanorings. J Am Chem Soc 130:16968–16977

Zachariah MR, Aquino MI, Shull RD, Steel EB (1995) Formation of superparamagnetic nanocomposites from vapor phase condensation in a flame. Nanostruct Mater 5:383–392

Coey JMD (1971) Noncollinear spin arrangement in ultrafine ferrimagnetic crystallites. Phys Rev Lett 27:1140–1142

Mørup S (2003) Spin-canting and transverse relaxation at surfaces and in the interior of ferrimagnetic particles. J Magn Magn Mater 266:110–118

Kolen’ko YV, Bañobre-López M, Rodríguez-Abreu C, Carbó-Argibay E, Deepak FL, Petrovykh DY, Cerqueira MF, Kamali S, Kovnir K, Shtansky DV et al (2014) High-temperature magnetism as a probe for structural and compositional uniformity in ligand-capped magnetite nanoparticles. J Phys Chem C 118:28322–28329

da Costa GM, De Grave E, Vandenberghe RE (1998) Mossbauer studies of magnetite and Al-substituted maghemites. Hyperfine Interact 117:207–243

da Costa GM (1995) Influence of nonstoichiometry and the presence of maghemite on the Mössbauer spectrum of magnetite†. Clays Clay Miner 43:656–668

da Costa GM, Blanco-Andujar C, De Grave E, Pankhurst QA (2014) Magnetic nanoparticles for in vivo use: a critical assessment of their composition. J Phys Chem B 118:11738–11746

Kamali-M S, Ericsson T, Wäppling R (2006) Characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles by Mössbauer spectroscopy. Thin Solid Films 515:721–723

Acknowledgement

S.N. acknowledges the financial support from startup funds at the Middle Tennessee State University. The authors thank Ms. Joyce Miller and Dr. James McBride for electron microscopy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Winsett, J., Moilanen, A., Paudel, K. et al. Quantitative determination of magnetite and maghemite in iron oxide nanoparticles using Mössbauer spectroscopy. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1636 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1699-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1699-2