Abstract

Case studies have been used by engineering ethics educators for several decades, following a path paved by legal educators in the late nineteenth century. Unfortunately, few of these cases connect the micro-ethical decisions of individual engineers with the macro-ethical consequences of their actions, leaving intact a long-standing division between ethics and equity in engineering education. Our paper highlights a curricular intervention aimed at helping bridge this ethics-equity divide. In particular, we document a three-year initiative to replace engineering ethics lectures with open-ended case study workshops. While early assessment results indicate that students found our workshops to be significantly more engaging than their first-year ethical compliance lectures, a recent episode of backlash demonstrates the ease and rapidity with which equity-based interventions can be derailed. Iterative optimization of our workshop in response to this critical incident suggests that engineering educators can bridge ethics with equity if they combine two pedagogical strategies emerging from distinct paradigmatic traditions: (1) infuse critical analyses into case study learning to avoid the pitfalls of moral relativism and (2) shift the tone of discussion from rational argumentation to respectful dialogue by including mindful listening activities.

Résumé

Depuis plusieurs décennies, les enseignants en éthique de l’ingénierie utilisent les études de cas, suivant la voie tracée par les professeurs de droit à la fin du 19e siècle. Malheureusement, peu de ces cas associent les microdécisions éthiques prises par des ingénieurs individuels aux macro conséquences éthiques provoquées par leurs actions, ce qui laisse intacte la division de longue date qui existe entre l’éthique et l’équité dans la formation en ingénierie. Notre article met en évidence une initiative visant à combler ce fossé entre l’éthique et l’équité dans les curriculums. En particulier, nous documentons une initiative d’une durée de trois ans où les cours/conférences traditionnels sur l’éthique ont été remplacés par des ateliers d’études de cas ouverts. Bien que les premiers résultats de l’évaluation indiquent que les étudiants ont trouvé les ateliers beaucoup plus intéressants que leurs cours/conférences de première année sur la conformité éthique, un épisode récent a montré la facilité et la rapidité avec laquelle les interventions fondées sur l’équité peuvent échouer. L’optimisation itérative de notre atelier en réponse à cet incident critique indique que les enseignants en ingénierie peuvent conjuguer éthique et équité s’ils combinent deux stratégies pédagogiques provenant de deux traditions paradigmatiques distinctes : d’une part l’infusion d’analyses critiques dans l’apprentissage fondé sur les études de cas pour éviter les écueils du relativisme moral, et d’autre part un changement de ton dans les discussions, de l’argumentation rationnelle vers le dialogue respectueux, grâce à l’inclusion d’activités d’écoute attentive.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

To an occupational outsider, engineers’ problem-solving confidence and competence are noteworthy. For generations, engineers across disciplines have applied the scientific method and design thinking to new problems, allowing them to innovate and adapt to a changing technical world with great speed, agility and reliability. While this process is a highly efficient and often effective method for solving technical problems, the implicit privileging of rational, convergent inquiry over subjective, divergent thought can limit engineers’ attention to important contextual details, with unintended consequences for marginalized populations. For example, facial recognition algorithms generated by software engineers and computer scientists working for Microsoft, IBM and Megvii incorrectly identified the gender of black female faces 35% of the time, while only misidentifying the gender of white male faces 1% of the time (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018; Lohr, 2018). If used exclusively for novelty guessing games, these algorithms are simply ineffective, but to the extent that they are adopted by the criminal justice system or health care practitioners to make incarceration or medical decisions, they can play a significant role in reifying societal inequities by race and gender. Here in Canada, engineers’ work has had territorial, health and welfare consequences for Indigenous communities who live along proposed pipeline paths, on manufactured flood plains, and downstream polluted waterways (Friesen & Herrmann, 2018; Jang et al., 2018; Roth, 2010), privileging the needs of developers and industry over the water quality, health, viability and land rights of Indigenous peoples. These two examples highlight the macro-ethical dimensions of engineers’ work, while signalling the integral relationship between ethics and equity. Briefly, we define ethics as “moral principles that govern a person’s or group’s behavior” and equity as “the quality of being fair or just.” The key argument we make in this article is that personal and professional ethics are irrevocably tied to social justice, leaving engineering ethics education incomplete when decoupled from equity. We further specify our critical social justice approach to achieving fairness by differentiating equity from equality. Equality builds on an assumption of baseline parity and involves standardized or impartial treatment of all individuals, while equity builds on an assumption of baseline discrimination and involves the removal of barriers to justice.

Our key contributions in this paper are to name and interrupt the historic decoupling of ethics from equity in engineering education and to reflect on ways to respond when emotionally charged disagreements inevitably arise. We do so, not as trailblazers, but as members of a growing international community of engineering educators who have begun to infuse critical social justice practices into the professional preparation of engineers (Cech, 2013; Pawley, 2017; Riley, 2012; Seron et al., 2011; Tonso, 2009). We view our national accreditation board as an influential partner in this process. As early as 2008, the Canadian Engineering Accreditation Board (CEAB) formally recognized the equity gap in engineering ethics education and sought to bridge it by naming “Ethics and Equity” as a learning outcome, or “Graduate Attribute” for Canadian engineers (CEAB, 2008, 2012). Canadian engineering programs were given one full accreditation cycle—ending in 2014—to implement programing related to the 10th Graduate Attribute—ethics and equity. This article documents our attempt to implement the CEAB’s call for change—an instructional innovation initiative to replace large-scale, transmission-style lectures with smaller-scale ethics and equity case study workshops at the Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering (FASE), at the University of Toronto.Footnote 1 In particular, we respond to the following four questions:

-

1)

Resource development: How did we generate engineering ethics and equity case studies that bridge micro- and macro-ethical concerns?

-

2)

Curricular integration: How have we integrated this resource into the formal engineering curriculum?

-

3)

Assessment: How does our ethics and equity workshop compare with undergraduate engineering students’ pre-existing ethics education experiences?

-

4)

Cautionary note: What did we learn from an instance of backlash?

Engineering Ethics and Equity Education: 3 Salient Themes in the Literature

Our initial scan of the literature on engineering ethics education produced few articles highlighting the intersection of ethics and equity. For this reason, we frame our study using three key themes drawn from two distinct bodies of literature. The first two themes address prominent pedagogical strategies for introducing ethical principles to engineering students while the third emphasizes the marginal status of equity in engineering education. The limited overlap between the first two bodies of literature and the third is evidence of a conceptual division between engineering ethics instruction and critical equity analysis in engineering education research and practice.

Theme 1: Rules and Codes Approach to Engineering Ethics Education

For nearly a century, engineers’ professional organizations have upheld the importance of their respective codes of conduct. As recently as fifty years ago, they began to refer to these documents as ethical codes (Tang & Nieusma, 2015; Vesilind, 1995). Engineering educators who centre these codes in their teaching tend to foreground professional engineers’ obligations to employers, clients, practitioners and society post licensure (Russell, 2008; Yarmus, 2010). Given the historical durability of these artifacts, it is not surprising that this approach remains a baseline feature of engineering ethics education in Canada (Haralampides et al., 2012; Roncin, 2013) and the USA (Colby & Sullivan, 2008; Herkert, 2000).

While some instructors guide students to internalize ethical codes using the bottom rung of Bloom’s (1956) taxonomy—recall only—most use a wider range of pedagogical strategies to help them apply and grapple with the content of these codes in specific educational and workplace contexts. For instance, Grimson (2007) documents a philosophical module he developed to enhance students’ self-understanding of their professional responsibilities; Andrews (2014) frames the code using traditional branches of ethical theory; Hill et al. (2013) derive lessons on civic professionalism from their analysis of engineers’ ethical codes in the UK and Germany; Roncin (2014) uses a video game to help his students navigate ethical dilemmas based on key clauses in their provincial codes; and Colby and Sullivan (2008) use professional codes—not only as a source of content but also as an institutional framework for teaching ethics. These strategies provide students with an accessible entry point to engineering ethics as defined by their respective professional organizations; however, instructors who depend on professional codes of conduct for content may unintentionally omit ethical principles that have not been codified, implicitly treating ethical codes as uncontested statements of moral good rather than historically contextualized settlements negotiated by professional regulators, their constituents and the public (Slaton, 2012; Tang & Nieusma, 2015; Vesilind, 1995). Beyond limiting students’ access to a comprehensive range of ethical principles, Swan et al.’s (2019) review of engineering ethics education between 1970 and 2018 suggests that when instructors foreground engineers’ professional codes, they implicitly favour two branches of ethical theory—utilitarianism and deontology—neither of which emphasizes equity.Footnote 2

Theme 2: Use of Case Studies in Engineering Ethics Instruction

A common approach to curricular integration of ethics, if not necessarily equity, involves teaching engineering students about “real-world” dilemmas through case study instruction (Bertha, 2010; Jennings & P, 2014; Jonassen et al., 2009; Lambert et al., 2016; Liang et al., 2016; Loendorf, 2009; Martin et al., 2018a, b; Martin et al., 2017; Nicometo et al., 2014; Richards & Gorman, 2004; Swan et al., 2019).

Our scan of the literature suggests that case study learning differs along two key dimensions—an inductive/deductive dimension and a micro/macro dimension. Cases designed around a particular philosophical or moral point prompt instructors to teach engineering ethics deductively—encouraging students to foreground a specific issue or apply a specific theory to their analysis of an event (Bertha, 2010; Liang et al., 2016; Loendorf, 2009). Those designed around a deeply contextualized dilemma, on the other hand, encourage instructors to take a more inductive approach—helping their students draw out a wider range of ethical lessons from the case (Jonassen et al., 2009; Martin et al., 2018a, b; Martin et al., 2017; Richards & Gorman, 2004). Inductive learning is more reflective of workplace realities, but open-ended case study analysis can easily descend into a “free for all” discussion, making it difficult for engineering educators to infuse equity issues into engineering ethics as a mandatory rather than optional element.

Shifting from analytic strategy to level of analysis, some engineering ethics educators use cases that foreground micro-ethical scenarios depicting individual practitioners facing difficult situations (Bertha, 2010; Jonassen et al., 2009; Loendorf, 2009), while others foreground macro-ethical situations highlighting socio-political consequences of engineering design principles (Martin et al., 2017; Martin et al., 2018a, b; Swan et al., 2019; Vallero, 2008; Warford, 2016). Both approaches have advantages and disadvantages. Micro-political cases tend to be more accessible and relatable to students with limited work experience, but their somewhat decontextualized nature can leave novice engineers with limited opportunities to connect their personal decisions with the unintended social consequences of those decisions. Macro-political cases, on the other hand, help students consider the consequences of engineers’ work, but many examples overemphasize disasters that may overwhelm or immobilize novice practitioners. Swan et al.’s (2019) analysis of engineering ethics case study teaching over the last five decades traces a recent shift from micro- to macro-ethical pedagogy. Martin and her colleagues stand among the growing chorus of voices advocating for this change (Martin et al., 2018a; Martin et al., 2017; Martin et al., 2018b), arguing that micro-political case studies fail to capture the metaphysical and epistemological dimensions of engineering. Interestingly, while macro-ethical case studies take social impact into account, they only occasionally, and often indirectly, address equity.

Theme 3: The Equity Gap in Engineering Education

The third and final theme we address in our literature review highlights the work of critical social justice scholars who examine the marginal status of equity issues in engineering education policies, practices and institutional spaces (Riley, 2008a, b, 2012, 2013, 2017; Riley & Lambrinidou, 2015; Riley & Pawley, 2011; Riley et al., 2015a, b). While few of these authors foreground classroom-based interventions, we have chosen to highlight their work because they raise important equity issues that cannot be easily apprehended through pedagogical means.

In her incisive paper, “Aiding and ABETing: The bankruptcy of outcomes-based education as a change strategy,” Riley (2012) draws our attention to the incompatibility of diversity initiatives with the US-based Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology’s (ABET) outcomes–based assessment practices, particularly given that equity is not named as a learning outcome. Herkert (2011) makes a similar point by documenting the absence of equity, diversity or inclusion (EDI) metrics in the National Academy of Engineering’s (NAE) “Grand Challenges for Engineering” document. This omission sends an implicit message to engineering educators that progress is possible without addressing equity. Moving from learning outcomes to institutional real estate, Riley (2013) maps the segregation of diversity booths in the American Society of Engineering Education’s (ASEE) exhibit hall, while her colleague, Pawley (2017), draws attention to the “diversity as exception” rather than “diversity as default” practice driving editorial decisions made by the Journal of Engineering Education. Supplementing Pawley’s point about restrictive publication standards, Riley (2017) powerfully highlights the homogenizing, exclusionary nature of “rigour” as an aspirational standard for engineering education research. Taken together, these five critical social justice analyses underscore the problematic yet all too common decoupling of ethics and equity in engineering education.

Three potential explanations for this decoupling include dualistic thinking that privileges technical over social aspects of the profession (Cech, 2014; Faulkner, 2000); dominant norms that restrict underrepresented engineers’ ability to secure belonging while raising equity issues (Dryburgh, 1999; Faulkner, 2007, 2009; Tonso, 2006a, b) and engineers’ ideological commitment to meritocracy and political neutrality which makes it difficult for them to accept the validity of equity-based decisions (Beddoes & Schimpf, 2018; Cech, 2013; Franzway et al., 2009; Seron et al., 2016). These three robust barriers to equity in engineering education suggest that we cannot simply rely on “rules and codes” or “case study learning” to effectively integrate equity issues into engineering ethics education.

Summary: Ethics and Equity Inhabit Different Spaces

The three themes we have explored in this literature review—(1) the “rules and codes” approach to engineering ethics education; (2) case study learning as a vehicle for engaging engineering students in ethical decision-making and (3) systemic barriers to equity in engineering—reveal the problematic decoupling of ethics and equity in engineering education research and practice. The first two themes address curricular approaches to ethics education in classroom contexts, while the third addresses equity silences in the field. Beyond locating ethics and equity at two distinct levels within engineering education, curriculum vs. field the authors whose work informs these three themes build on two distinct theories of change. The first two draw on a pragmatic, evolutionary theory of personal change (Dewey, 1916, 1938) positioning educators as classroom-level actors with a duty to support students’ ethical development, while the third draws on a critical, systemic theory of societal change (Freire, 1985; Habermas, 1987; Hooks, 1994; Marx & Engels, 1906/2010), urging all of us to examine and interrupt the ways in which we tacitly uphold structures that reproduce patterns of privilege in society. Both groups of educators are committed to socially just change in engineering education, but they approach this work from perspectives that often seem counter-productive to one another. We believe there is space for multiple approaches to social justice. In fact, the two co-authors of this article tend to locate ourselves in different paradigms. It is through our long-term commitment to respectful listening across epistemological divides that we have learned to productively integrate ethics and equity into engineering education. Our collaboration is not based on the achievement of consensus or the avoidance of conflict; it is based on a joint commitment to fostering a more just world for our students, our colleagues and ourselves. This article documents our efforts to develop, integrate, assess and optimize an evidence-based ethics and equity intervention at the Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering at the University of Toronto.

Theoretical Perspective—Critical Social Justice

Our initial manuscript foregrounded a critical social justice perspective. We address inter-paradigmatic dialogue in our discussion.

One way to infuse equity issues into engineering ethics education is to adopt a critical social justice perspective that embraces equity over equality, as an indicator of fairness. We use the term equality to denote impartial or standardized treatment and the term equity to signify active intervention in discriminatory practices. In terms of theoretical traditions, the equality approach to fairness draws on liberal theories of justice (Rawls, 1971; Sen, 1973), while the equity approach draws on critical social justice theory (Freire, 1998; Gramsci, 1971; Habermas, 1979; Hooks, 2003; Marx, 1906). Liberal social justice theory frames citizens as individuals with the right to equal opportunities, while critical social justice theory frames inequitable outcomes at the group level as evidence of widespread discrimination in our education, economic and governance systems. (Please see Table 1 for the three key distinguishing features of the two theories.)

Theorists and educators who advocate for equal treatment often build on the assumption that we access knowledge and truth in objective ways, that the world is fair and that existing social inequalities are the product of individual competence or effort. In contrast, those who advocate for equitable treatment are more inclined to build on the assumption that we cannot access truth independent of our experiences, perspectives, values or social locations and that current inequalities are a product of systems, structures, policies and practices that unfairly advantage some groups over others. When it comes to action, equal treatment involves affording all individuals the same opportunity to achieve, while equitable treatment involves removing barriers to discrimination at the group level.

We situate our analysis in the latter tradition, operationalizing our critical social justice lens with three key concepts: Snyder’s (1970) “hidden curriculum,” McIntosh’s (2003) “invisible knapsack of privilege” and Faulkner’s (2009) “dripping tap effect.” Snyder’s “hidden curriculum” foregrounds the tacit systems of oppression at work in our institutions; Faulkner’s “dripping tap effect” reveals the collection of subtle discriminatory practices that might not seem significant on their own but have a collective negative impact on the inclusivity of institutional culture and McIntosh’s “invisible knapsack” itemizes the subtle, unearned advantages we carry around with us when our gender, race, ethnicity, socio-economic class, sexuality and other demographic markers align with broader patterns of privilege in society. Together, these three concepts allow us to analyze an instance of backlash that occurred in one of our workshops by making institutional culture, discrimination and unearned privilege apprehensible to individuals who may not otherwise see them.

Project Context I: Resource Development

How did we generate engineering ethics and equity case studies that bridge micro- and macro-ethical concerns?

Our project began in June 2014 as a faculty-sponsored instructional innovation project to develop ethics and equity case studies for an undergraduate engineering course. In consultation with our institutional Ethics Review Board, we completed a quality assurance application and were granted permission to conduct the project. As part of this process, we were required to be clear that any publication emerging from the project would include a line stating that our conclusions or learnings were not gained through research for wide application, but were rather a product of a Quality Improvement/Quality Assurance project carried out in a local context.

After completing this process, we began conducting career history interviews with 15 engineers—highlighting an ethical dilemma they had faced over the course of their careers. All participants had at least one year of relevant work experience. They ranged in age from 18 to 75, were trained in eight different engineering disciplines, worked in more than a dozen organizational contexts and roughly represented the demographic make-up of Canadian society. We recorded and transcribed the interviews verbatim, inductively analyzed the transcripts for key themes and then generated brief case study narratives highlighting each of the 15 critical incidents shared by participants. We masked the names of individuals and organizations and altered several identifying features, but otherwise left participants’ narratives intact.

While we initially planned to generate micro-ethical case studies, saving a discussion of macro-ethical consequences for our workshop, we found that the individuals we interviewed actually vacillated between micro- and macro-level concerns during their interviews. Without exception, all 15 participants connected micro-level concerns (what should I do in this situation?) with broader socio-political trends (environmentalism, safety, globalization, academic integrity, consequences of foreign aid, sexual harassment, racism, homophobia, sexism, sustainability, professional responsibility, health and disclosure of proprietary information). Additionally, and directly related to our intervention, nine participants explicitly infused equity issues into their ethical narratives. The presence of nine equity-infused narratives in response to an interview question prompting participants to talk about ethical dilemmas demonstrates that for at least some engineers, there was an integral, embodied relationship between ethics and equity in the context of their professional lives.

Project Context II: Curricular Integration

How have we integrated this resource into the formal engineering curriculum?

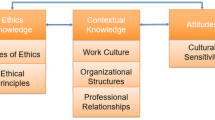

Over the past five years, we have used three curricular integration strategies, presented in order of uptake: delivering ethics and equity workshops to students by invitation from their course instructors (9 courses, 25 offerings), consulting with instructors willing to take the lead on integrating our cases into their classes (4 courses, 11 offerings) and co-constructing discipline-specific ethics and equity modules in collaboration with technical course instructors (1 course, 1 offering). Our case studies have been integrated into classes as small as 10 and as large as 400, but most have 50–70 students. We have been most successful in securing invitations to elective complementary studies courses, with growing interest from first-year design and fourth-year professional practice instructors. Until recently, we have had limited interaction with core technical instructors. Workshop content, structure and timing differ in each course to accommodate instructor preferences and course content, but most of our workshops include six elements. (Please see Fig. 1 for a list of these elements.)

Workshop elements. a We expose students to five ethical theories using a traditional lecture format: Aristotle’s Virtue Ethics, Kant’s Duty Ethics/Deontology, Mill’s Utilitarianism, Locke’s Rights-based ethics and Noddings’ ethic of care. b After introducing students to four equity concepts, we engage them in a “four corners” activity. We invite them to identify the concept with which they most resonate and walk to a corner of the room assigned to that concept. They then discuss why this concept resonated with them in small groups and share examples of how it helps them better understand an event in their lives. We conclude the activity by inviting students from each of the four corners to share their insights with the whole class. We use the following four concepts: McIntosh’s “invisible knapsack,” Faulkner’s “dripping tap effect,” Faulkner’s “in/visibility paradox” and Connel’s “hegemonic masculinity”

Five years into the project, our case studies are experiencing greater levels of institutional recognition, reflecting a growing commitment to equity, diversity and inclusion in the faculty. We view this institutional commitment as a sign of progress, but ethics and equity remain on the margins of the formal engineering curriculum—primarily being integrated through elective courses or drop-in workshops delivered by a small cadre of 10–15 faculty and staff doing this work off the sides of our desks.

Findings I: Assessment

How does our ethics and equity case study workshop compare with undergraduate engineering students’ pre-existing ethics education experiences?

We assessed our pedagogical intervention using a pre-post survey constructed to compare students’ experiences in our ethics and equity case study workshop with their previous ethics education. As illustrated in Table 2, students in our sample were considerably more senior, but otherwise representative of the population of undergraduate engineering students in the faculty during the 2014/15 academic year.

We invited participants from the first four workshops to rate their previous ethics education and our intervention along five dimensions that emerged from our literature review: practicality, relatability, authenticity, engagement and helpfulness when grappling with ambiguity. After removing incomplete surveys, we ran paired sample t tests on participants’ pre- and post-workshop effectiveness ratings along each dimension. Our baseline comparator was a large (800 students), mandatory first-year engineering ethics seminar that exposed students to the PEO Code of Ethics, faculty-wide plagiarism policies and case studies of engineering failures. More than 90% of the students in our sample (n = 104) took this course.Footnote 4 We used a two-tailed alternative hypothesis to examine the probability of arriving at a non-zero difference between our workshop and the baseline course by chance. For each significant difference (p < .05), we manually calculated the standard effect size (d), using Green and Salkind’s (2017) convention for small = .2, medium = .5 and large = .8 effects. Our survey findings indicate that students experienced our workshop to be significantly more practical, relatable, authentic, engaging and helpful when grappling with ambiguity than their previous ethics education—with particularly large effect sizes for authenticity and engagement. (Please see Table 3 for our results.)

We concluded the survey by asking participants to provide us with open-ended feedback about our case study workshop. (Please see Table 4 for a list of the five most frequently cited themes, along with illustrative quotations.) Together, our statistical and thematic analyses of student survey data indicate that participants found our workshop to be significantly more engaging than large-scale engineering ethics lectures. While one might expect case study learning in classes of 50 to 70 students to be more engaging than ethical compliance lectures in a class of 800, the fact that students found our workshops to be significantly more practical, relatable, authentic and useful when grappling with ambiguity when compared with their previous ethics education suggests that the relative effectiveness of our pedagogical innovation cannot be reduced to class size. This finding is promising, but it behoves us to identify an important methodological limitation of our assessment strategy. Recall that our case study workshop was the product of a quality improvement initiative, not an experimentally designed research project. As such, we cannot treat students’ previous engineering ethics education as a control group. It is likely that factors such as maturation, reduced class size and active learning pedagogy led workshop participants to view our ethical intervention more favourably than their first-year course. While we cannot isolate the variables that led to student engagement, unsolicited feedback from many students suggests that they appreciated having the opportunity to put themselves in the shoes of practicing engineers. We now turn to an incident illustrating that while many students felt engaged in our workshop, open-ended case study learning is not without its challenges.

Findings II: Cautionary Note

What did we learn from an instance of backlash?

In March 2018, we delivered an ethics and equity workshop to 50 students enrolled in an undergraduate engineering leadership class. This was the fourth time we had used Case Study #6: “It’s a shame there aren’t more women here.” Briefly, the case highlights the experience of Robin,Footnote 5 an engineering intern who overheard one of his colleagues—Frank—refer to female engineers at their public utility office as an insufficiently large dating pool. Key actors in the case include Robin (the intern we interviewed for the case), Frank (the intern who allegedly made a sexually objectifying comment about women in the office) and three members of their project team who had overheard the comment. There are no female engineers featured in the case.

Previous workshops containing case study six had elicited student responses ranging from rational inquiry to thoughtful engagement to mild irritation to deep empathy, but for the first time, a student who we call Peter haltingly expressed his identification with Frank. Peter’s identification with Frank opened the door to a “men’s rights” discourse moments before the end of class, countering the equity work we had done as a group for the previous three hours. We have chosen to share this teachable moment because it illustrates a challenge instructors may face while attempting to integrate equity into engineering ethics education—how to meaningfully respond to backlash in a heterogeneous classroom setting when students’ previous experiences with privilege and discrimination are unknown to us. After presenting his group’s analysis, Peter paused for a moment and then cautiously shared his perspective that Frank had not done anything wrong:

What’s wrong with dating people at work? You’re always trying to get us to express our individuality. It’s a leadership class. Are you trying to restrict my freedom of speech?

Immediately following Peter’s comment, two of his male colleagues—Adam and Rick—backed him up:

What he’s trying to say is that men have lost our ability to speak our minds. What about men’s rights?

Everything is so politically correct now. I thought universities were supposed to be defenders of free speech.

Several of Peter’s female classmates, who had shared examples of discrimination during an equity-based activity earlier in the workshop, raised their hands, while others spoke under their breath at nearby tables:

Are you kidding?

One of them, Anita, challenged Peter’s perspective by invoking a discourse of professionalism:

I don’t think Robin’s point was that people shouldn’t date at work. He just wanted to be a professional, to use his internship to develop his technical skills. Just like Robin, I go to work to be part of interesting projects with other engineers who value my technical skills, not to find a boyfriend. It makes me uncomfortable when people on my team spend project time trying to ask me out.

With Anita’s reframing comment, class was over. Despite two decades of equity education experience, we failed to intervene in a discussion that centred the very issue we had been called in to teach—equity. This humbling experience taught us five discrete lessons: (1) despite our institutional position as ethics and equity educators, we remain learners in this domain; (2) equity requires more sustained time and attention than a three-hour drop in workshop affords; (3) defining terms and exposing students to ethical theories do little to help them examine their own roles in the everyday reproduction and maintenance of inequity; (4) equity cannot be taught using exclusively cognitive means because it elicits deep emotions in all of us and (5) open-ended case studies can mistakenly lead students to believe that all paths forward are equally defensible. Our discussion provides readers with an equitable alternative to the moral relativism underlying lesson number 5.

Discussion: Making the Invisible Visible

In an effort to drive our own thinking further, we analyze this instance of backlash through the critical social justice lens we presented earlier in the article. Recall the three equity concepts we identified in our theoretical perspective—Snyder’s (1970) “hidden curriculum” foregrounds the tacit systems of oppression at work in our institutions; Faulkner’s (2009) “dripping tap effect” reveals the collection of subtle discriminatory practices that might seem insignificant on their own but have a collective negative impact on the inclusivity of institutional culture and McIntosh’s (2003) “invisible knapsack” itemizes the subtle, unearned advantages we carry around with us when our demographic markers align with broader patterns of privilege in society.

-

1.

Hidden curriculum—How does the overt messaging system of the faculty compare with students’ EDI experiences?

Formal documents posted on the University of Toronto Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering website, a five-year academic plan highlighting the importance of diversity, and a series of EDI posters, stickers and artifacts communicate a clear message about the faculty’s position on equity, diversity and inclusion. Posters include racially and gender diverse images, safe space stickers are commonly featured on office doors, and the faculty website has increasingly highlighted our institutional progress toward gender parity. Fortunately, these equity-informed changes extend beyond a public relations campaign. The Dean has scaled up outreach efforts to young women interested in engineering and has recently appointed Special Advisors on Indigenous and Black inclusion, to make our programs more inclusive to Black and Indigenous students. In June 2019, she created a new position—Assistant Dean, Director of Diversity, Inclusivity and Professionalism to integrate EDI efforts into the institutional fabric. In short, the official messaging system of the faculty as well as several centrally mandated initiatives, indicate that our institution values equity, diversity and inclusion.

To reveal the hidden curriculum of engineering education, however, we must examine the extent to which our, “You Belong” message reflects the everyday realities of students, staff and professors who teach, learn and work in our classrooms, labs and offices. Which students feel like they belong? Which students require a poster campaign to be assured that they belong? Our workshop exposed the hidden curriculum by inviting students to connect their personal experiences with one of four equity concepts. By privileging their experientially embedded knowledge over objective truth, we learned that design team projects, frosh week experiences, clubs and technical coursework did not always feel inclusive to some of the female and racialized students in the class. That is, despite first-year admission levels approaching gender parity and an extensive anti-racism poster campaign, demographically underrepresented students continue to experience discrimination. We flesh out their experiences more fully below.

-

2.

Dripping tap effect—What impact might a “men’s rights” discourse have had on students who regularly experience gender-based discrimination in their program?

Nearly two hours before Peter’s comment, several students shared personal experiences with discriminatory “drips” that occurred during their engineering education. Most of these students were women, but a few racialized men, including Peter, joined the group. They told stories about regularly being asked to take notes in their design team projects, having their technical skills questioned, repeatedly being asked where they were from, being the only female member of a team, trying to tune out engineering chants that sexually objectified women, being asked out on dates repeatedly while trying to focus on lab work, having friends talk about their appearance rather than their coding abilities, encountering expectations that they carry the emotional load or organizational duties of team projects, having their commitment to the engineering student community challenged if they opted not to drink for religious reasons and being treated more formally or politely than their white, male peers. The cumulative effect of these drips was a clear erosion of inclusivity in engineering education experienced disproportionately by women and racialized men.

These pre-existing “drips” meant that for some students, Peter’s classification of men’s sexual freedom as a basic human right, added another painful data point to a mounting body of evidence that they did not belong in engineering. In contrast, for students who had never experienced gender-based drips, there were multiple options: they could accept Peter’s claim that men’s sexual freedom was a basic human right to be protected by constitutional democracy; they could disregard his comment as an emotional outburst inconsistent with STEM education; they could empathize with their female peers or they could begin to consider how they were implicated in the broader system of drips. Thus, it was experientially easier for them, than for students experiencing daily “drips,” to retain their decision-making authority.

-

3.

Invisible knapsack: How does unacknowledged privilege incline some engineering students to accept a men’s rights discourse?

After the workshop, we learned from the course instructor that Peter, Adam and Rick had been exposed to a men’s rights discourse outside of class which all of them had found compelling. In contrast to social movements like feminism and civil rights that are historically anchored in the fight for enfranchisement—a right already enjoyed by white men—the men’s rights movement is driven by the desire to protect pre-existing levels of unearned advantage. Men clearly deserve to have their human rights protected, but the “men’s rights” argument, like the “all lives matter” protest to the Black Lives Matter movement, is an expression of backlash to social justice. When unearned advantages are invisible to those who benefit from them, the gains of other groups may be experienced as personal losses. This experience of perceived loss leaves students vulnerable to anti-EDI arguments.

Returning to the classroom incident, Peter’s defense of Frank’s right to sexual freedom must be read in relation to the systemic privileges he enjoyed as a male engineering student at the University of Toronto in 2018. By unpacking his “invisible knapsack of privilege,” we find that Peter and his male colleagues remain the numeric majority in engineering classrooms, they can find a washroom on every floor of engineering buildings, they often see their sex reflected in tenure stream faculty, they rarely have to speak on behalf of their sex in engineering classrooms, they are rarely the only ones of their sex in a design team and they do not have to worry that their professors or peers will attribute their engineering program admission to their sex. In short, while Peter, Adam and Rick may feel like they are losing ground in comparison to their fathers or grandfathers, they continue to be systemically advantaged over their female peers in many ways. Material privileges aside, their perception of loss may increase their attraction to a men’s rights discourse.

Critical Analysis Provides us with a Mechanism for Infusing Engineering Ethics with Equity

Synthesizing these three lines of analysis, we have learned that (1) a subset of students continues to experience discrimination despite a recent proliferation of EDI initiatives in the faculty; (2) persistent discrimination makes the faculty more inclusive to some students than others; and (3) male engineering students continue to experience material and symbolic privileges over their numerically underrepresented female peers. When these three lines of analysis remain masked, it is possible to imagine the men’s rights movement as a branch of our constitutionally protected human rights, but when they are made explicit, it becomes clear that asking men to respect women’s right to sexual consent is not an erosion of their own human rights—it is a condition of their membership in a society that requires its citizens to do no harm. When a woman expects to be viewed as a technically competent professional rather than a sexual object, she is not doing harm to her heterosexual male colleagues—she is acknowledging her right to participate in a community of engineers alongside them.

The critical social justice analysis we have conducted above fulfills an important function in engineering education by making tacit systems of oppression explicit to those who may not otherwise apprehend inequities, but it does little to deter backlash. By taking a moment to stand in Peter’s shoes after the incident, we began to appreciate that sudden exposure to systemic inequities earlier in the workshop may have induced anxiety in him. While we believe that mild discomfort is a product of learning (even for calculus), it is our intention to support the development of our students, not to provoke defensiveness in them. As such, we now turn our attention to practical strategies for integrating ethics and equity into engineering education across experiential, epistemological and ideological divides.

So? What Can I do? Implications for Engineering Educators

Few people argue against making the world a better place, but we all have different perspectives on what this entails. Our future success as engineering ethics and equity educators depends on finding ways to connect with others across paradigms. To ease this process, we have identified five ground rules for respectful interaction, drawn from our experiences integrating ethics and equity into engineering education:

-

Mindfully listen to the perspectives of those with whom you disagree;

-

Clearly communicate your own perspectives and identify their experiential source;

-

Solicit feedback from students, staff and faculty rooted in paradigms different from your own;

-

Be willing to change your mind in response to the contributions of others and

-

Take primary responsibility for your own learning

These five ground rules set the stage for respectful dialogue across a diversity of worldviews, but they fall short of practical guidance for engineering educators who have never integrated ethics or equity into their engineering coursework. While we cannot feasibly prescribe a set of failsafe recommendations for engineering ethics and equity instruction, we are happy to share insights from our experience facilitating 25 ethics and equity workshops in nine undergraduate engineering courses. Over the years, we have found that while most participants appreciate the opportunity to put themselves in the shoes of professional engineers, a few continue to feel disoriented by our divergent pedagogy. Some express discomfort leaving class without the right answer, others describe feeling overwhelmed by the number of issues raised in the case and others still resist the intrusion of social issues into their technical education. In true engineering fashion, three students even offered to solve our divergence problem by creating a flow chart to aid the decision-making process of future workshop participants. We have resisted the flow chart solution because we believe it is professionally valuable for engineering students to learn how to grapple with ambiguity, but we have integrated each layer of student feedback into successive offerings by scaffolding EDI learning. To this end, we have:

-

Added a brief lecture feature to introduce students to five prominent ethical theories;

-

Defined unfamiliar EDI-related terms;

-

Prompted students to apply one equity concept to their personal experiences;

-

Cued students to reflect on the relationship between their decision-making processes and those of others in their teams;

-

Supplemented the PEO code of conduct with the IEEE code to demonstrate the diversity and historical malleability of ethical codes;

-

Helped students contextualize small-group case study discussions through an organizational mapping exercise and

-

Eased them into divergent thinking by prompting them to brainstorm multiple issues faced by key actors in each case.

We believe these student-inspired changes have improved the accessibility of our workshop, but no level of preparation on our part will make equity-infused ethical discussions comfortable for students or instructors as a whole. Beyond the fact that there is no generalizable strategy for arriving at the “correct” answer to any ethical dilemma, our experience is that equity issues can amplify students’ pre-existing discomfort with ethically ambiguous situations. Some students are triggered by EDI discussions because they resurface pain caused by a lifetime of daily discrimination. Others feel overwhelming shame as they learn about the unintended negative consequences of their actions. Some mourn the loss of status, privilege or control in the classroom—a space where they once felt competent. As these emotions surface, underlying tensions between lab partners, roommates, teammates and cohorts become an explicit part of the classroom dynamic making it difficult to learn a new set of socio-technical competencies.

After consulting with experienced equity educators and reading a book on overcoming ideological divides in EDI work (Choudhury, 2015), we now use two strategies to prime students for this experience: a mindful listening exerciseFootnote 6 and an introduction to equity learning zones.Footnote 7 We began integrating the mindful listening activity into our workshops after the backlash incident we describe in this article because we wanted to shift the tone of classroom discourse from rational argumentation to respectful dialogue. So far, we have found that it has helped students draw on their own experientially based knowledge about discrimination while honouring the experiences of their peers. More recently, we have begun using an equity-specific version of Vygotsky’s (1978) “zone of proximal development,” to help students monitor their emotional engagement levels. Vygotsky’s constructivist learning theory suggests that students cannot learn when they are either over- or under-stimulated. Similarly, our student affairs colleagues have identified the sweet spot for EDI learning as a “stretch” zone located between a “comfort” zone where little new learning takes place and a “panic” zone where anxiety interferes with learning. After prompting students to reflect on their emotional zone at the beginning of the workshop, we invite those in the panic zone to contact a supportive friend, speak to a facilitator, take a breath or take a temporary break from class. We then help them distinguish between three types of discomfort—the discomfort of feeling marginalized, the discomfort of feeling like they are losing ground and the discomfort of feeling like they are implicated in the marginalization of others.

Finally, to reduce the likelihood that novice EDI analysts feel immobilized by webs of discrimination, we introduce them to the notion of “bounded agency” (Archer, 2003). This concept allows us to discuss legal, organizational and socio-political constraints to human action, without accepting the deterministic argument that these constraints leave actors with no way forward. Our work as engineering leadership educators builds on the assumption that engineers have some level of agency to shape their respective responses to a situation. In fact, it is our commitment to leadership development that prompted us to use open-ended case study learning as the central feature of our ethics and equity intervention. Unfortunately, this pedagogical approach left us vulnerable to an “anything goes” mentality that derailed equity analyses in a recent workshop. When it comes to engineering ethics and equity, open-ended case study learning cannot become a “free for all,” with an infinite number of equally defensible solutions, or a vehicle for transmitting a single moral truth to students. It must become an exercise in “praxis” (Freire, 1998)—an iterative process involving the comparison of ethical theories with the wide range of actions available to individuals who must live with the technical and social consequences of their decisions.

Conclusions

The Canadian Engineering Accreditation Board (CEAB) requires all degree granting engineering programs in the country to integrate ethics and equity into students’ curricular experiences, but it can be challenging for engineering educators to design resources in support of new learning outcomes, particularly when those outcomes fall outside their respective areas of expertise. How can engineering educators who may be new to EDI analysis help students address ethics and equity in the context of their professional lives? While we lack a simple answer to this question, we have gained five key insights from our experience delivering ethics and equity case study workshops to more than 1000 undergraduate engineering students at the University of Toronto. Please see Table 5 for a summary of our key findings and corresponding implications for engineering educators.

Ethics and equity are not new content areas to be learned in class, nor are they human factor design constraints extraneous to the real engineering problem. They are integral to the personal and professional lives of engineers, connecting micro-ethical dilemmas with macro-ethical consequences from a range of social locations. Engineering educators, professional engineers and engineering students across institutional contexts must habitually infuse our everyday ethical decisions with equity considerations—considering at each step, how our own values, experiences and beliefs shape our actions and how these actions shape the social conditions of others. This requires ongoing practice within a diverse community of engineering educators committed to catalyzing ethical and equitable change in the profession across epistemological commitments. To borrow the metaphor of structural integrity from our colleagues in civil engineering, equity is the rebar that affords engineering ethics educators the strength we need to bring about meaningful social change.Footnote 8

Notes

This project is one of many EDI initiatives in the faculty. It was supported by the Dean’s EIIP (Engineering Instructional Innovation Program) grant, but was not centrally driven.

Recently, two discipline-based professional societies—the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers and American Society of Civil Engineers—have led the effort to infuse equity into engineering ethics by adding non-discrimination and fair treatment clauses to their respective codes of conduct.

The only students in our sample who were not required to take this course were those registered in Engineering Science in first year. Their ethics requirement involves a second-year course called “Engineering, Society and Critical Thinking.” Eight of the 112 students in our sample were in engineering science.

All names of case study actors and workshop participants are pseudonyms.

We have integrated a mindful listening exercise into the workshop—introduced to us by our colleague Dr. Jasjit Sangha, Learning Strategist, Academic Success Centre at the University of Toronto.

We borrowed this framework from our colleague Máiri McKenna Edwards, Coordinator of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion training at the University of Toronto.

This is as true in engineering education as in K-12 classrooms more familiar to the readership of this journal. While we are not familiar with this literature, we have come to understand that several STEM education frameworks integrate ethics and equity into math, science and technology education. These include SSI (Socio-Scientific Issues), SAQ (Socially Acute Questions) and STSE (Science, Technology, Society and the Environment). We look forward to learning more about these frameworks through future collaboration with educators and researchers in K-12 STEM education.

References

Andrews, G. C. (2014). Canadian Professional Engineering and Geoscience: Practice and Ethics (5th). Toronto: Nelson.

Archer, M. S. (2003). The process of mediation between structure and agency. In Structure, Agency, and the Internal Conversation (pp. 130-150). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Beddoes, K., & Schimpf, C. (2018). What’s wrong with fairness? How discourses in higher education literature support gender inequalities. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 39(1), 31-40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2016.1232535

Bertha, C. (2010). How to teach an engineering ethics course with case studies. Paper presented at the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference & Exposition, Louisville.

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay Co Inc.

Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018). Gender shades: Intersectional accuracey disparities in commercial gender classification. Paper presented at the Machine Learning Research Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency, New York University, NY.

CEAB. (2008). Accreditation Criteria and Procedures 2008. Retrieved from Ottawa, ON.

CEAB. (2012). Canadian Engineering Accreditation Board Accreditation Criteria and Procedures. Retrieved from Ottawa.

Cech, E. (2013). The (mis)framing of social justice: Why ideologies of depoliticization and meritocracy hinder engineers’ ability to think about social injustices. In J. C. Lucena (Ed.), Engineering for Social Justice: Critical Explorations and Opportunities (Vol. 10, pp. 64-84). Dordrecht: Springer.

Cech, E. (2014). Culture of disengagement in engineering education? Science, Technology, & Human Values, 39(1), 42-72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243913504305

Choudhury, S. (2015). Deep Diversity: Overcoming Us vs. Them. Toronto: Between the Lines.

Colby, A., & Sullivan, W. M. (2008). Ethics teaching in undergraduate engineering education. Journal of Engineering Education, 97(3), 327-338. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2008

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. New York: Macmillan Co.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York: Macmillan.

Dryburgh, H. (1999). Work hard, play hard: Women and professionalization in engineering-Adapting to the culture. Gender & Society, 13(5), 664-682. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/089124399013005006

Faulkner, W. (2000). Dualisms, hierarchies and gender in engineering. Social Studies of Science, 30(5), 759-792. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/030631200030005005

Faulkner, W. (2007). "Nuts and bolts and people": Gender-troubled engineering identities. Social Studies of Science, 37(3), 331-356. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312706072175

Faulkner, W. (2009). Doing gender in engineering workplace cultures 1: Observations from the field. Engineering Studies, 1(1), 3-18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19378620902721322

Franzway, S., Sharp, R., Mills, J. E., & Gill, J. (2009). Engineering ignorance: The problem of gender equity in engineering. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 30(1), 89-106.

Freire, P. (1985). Reading the world and reading the word: An interview with Paulo Freire. Language Arts, 62(1), 15-21.

Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage (P. Clarke, Trans. Vol. 7). New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Friesen, M. R., & Herrmann, R. (2018). Indigenous knowledge, perspectives, and design principles in the engineering curriculum. Paper presented at the Canadian Engineering Education Association Annual Conference, Vancouver, BC.

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks (G. N. Smith, Trans.). New York: International Publishers.

Green, S. B., & Salkind, N. J. (2017). Using SPSS for Windows and Macintosh: Analyzing and Understanding data (8th). Hoboken: Pearson.

Grimson, W. (2007). The philosophical nature of engineering: A characterisation of engineering using the language and activities of philosophy. Paper presented at the 114th Annual ASEE Conference and Exposition, Honolulu, HI.

Habermas, J. (1979). Communication and the evolution of society. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Habermas, J. (1987). Lifeworld and system: A critique of functionalist reason. In Theory of Communicative Action (Vol. 2). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Haralampides, K., MacIsaac, D., Diduch, C., & Wilson, B. (2012). Engineering and social justice through an accreditation lens: Expectations and learning opportunities for ethics and equity. Paper presented at the Canadian Engineering Education Association Annual Conference, Winnipeg, MB.

Herkert, J. R. (2000). Engineering ethics education in the USA: Content, pedagogy and curriculum. European Journal of Engineering Education, 25(4), 303-313. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03043790050200340

Herkert, J. R. (2011). Yogi meets Moses: Ethics, progress and the grand challenges for engineering. Paper presented at the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference and Exposition, Vancouver, BC.

Hill, S., Lorenz, D., Dent, P., & Lutzkendorf, T. (2013). Professionalism and ethics in a changing economy. Building Research & Information, 41(1), 8-27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2013.736201

Hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge.

Hooks, B. (2003). Teaching community: A pedagogy of hope. New York: Routledge.

Jang, T., Kaljur, L., Paling, E., Scholey, L., Bernard, A., Owen, B., …, & Ofenheim, J. V. (2018). #TrackingTransMountain: A database of how Indigenous communities are affected by Kinder Morgan’s pipeline proposal. APTN National News. Retrieved August 15, 2019 from https://aptnnews.ca/2018/05/25/trackingtransmountain-a-database-of-how-indigenous-communities-are-affected-by-kinder-morgans-pipeline-proposal/. Accessed 15 Aug 2019.

Jennings, D. F., & P, N. B. (2014). Teaching ethics and leadership with cases: A bottom-up approach. Paper presented at the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference & Exposition, Indianapolis, IN.

Jonassen, D. H., Shen, D., Marra, R. M., Cho, Y.-H., Lo, J. L., & Lohani, V. K. (2009). Engaging and supporting problem solving in engineering ethics. Journal of Engineering Education, 98(3), 235-254. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2009

Lambert, S., Newton, C., & Effa, D. (2016). Ten years of enhancing engineering education with case studies-insights, lessons and results from a design chair. Paper presented at the Canadian Engineering Education Association Annual Conference, Halifax, NS.

Liang, V., Jasensky, Z., Moore, M., Rogers, J. F., Pfeifer, G., & Billiar, K. (2016). Teaching engineering students how to recognize and anlayze ethical scenarios. Paper presented at the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference & Exposition, New Orleans, LA.

Loendorf, W. (2009). The case study approach to engineering ethics. Paper presented at the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference & Exhibition, Austin, TX.

Lohr, S. (2018). Facial recognition is accurate, if you’re a white guy. The New York Times. Retrieved August 15, 2019 from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/09/technology/facial-recognition-race-artificial-intelligence.html.. Accessed 15 Aug 2019.

Martin, D. A., Conlon, E., & Bowe, B. (2017). A constructivist approach to the use of case studies in teaching engineering ethics. Paper presented at the International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning: Teaching and Learning in a Digital World, Budapest, Hungary.

Martin, D. A., Bowe, B., & Conlon, E. (2018a). A case for case instruction of engineering ethics. Paper presented at the CREATE (Contributions to Research in Engineering and Applied Technology Education) Conference, Dublin, Ireland.

Martin, D. A., Conlon, E., & Bowe, B. (2018b). A case for case instruction of engineering ethics. Paper presented at the SEFI (European Society for Engineering Education) Annual Conference: Creativity, innovation and entrepreneurship for engineering education excellence, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Marx, K. (1906). Capital: A critique of political economy. New York: The Modern Library.

Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1906/2010). Bourgeois and Proletarians. In R. Altschuler (Ed.), Seminal Sociological Writings: From Auguste Comte to Max Weber (pp. 11-22). New York: Gordian Knot Books.

McIntosh, P. (2003). White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack. In S. Plous (Ed.), Understanding Prejudice and discrimination (pp. 191-196). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Nicometo, C. G., Nathans-Kelly, T., & Skarzynski, B. (2014). Mind the gap: Using lessons learned from practicing engineers to teach engineering ethics to undergraduates. Paper presented at the IEEE International Symposium on Ethics in Engineering, Science, and Technology (ETHICS), Chicago, IL.

Pawley, A. L. (2017). Shifting the "default": The case for making diversity the expected condition for engineering education and making whiteness and maleness visible. Journal of Engineering Education, 106(4), 1-3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20181

Rawls, J. (1971). A Theory of Justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Richards, L. G., & Gorman, M. E. (2004). Using case studies to teach engineering design and ethics. Paper presented at the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference & Exposition, Salt Lake City, UT.

Riley, D. M. (2008a). Engineering and Social Justice. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool Publishers.

Riley, D. M. (2008b). LGBT-Friendly workplaces in engineering. Leadership and Management in Engineering, 8(1), 19-23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1532-6748(2008)8:1(19)

Riley, D. M. (2012). Aiding and ABETing: The bankruptcy of outcomes-based education as a change strategy. Paper presented at the American Society of Engineering Education Annual Conference and Exposition, San Antonio, TX.

Riley, D. M. (2013). The island of other: Making space for embodiment of difference in engineering. Paper presented at the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference and Exposition, Atlanta, GA.

Riley, D. M. (2017). Rigor/us: Building boundaries and disciplining diversity with standards of merit. Engineering Studies, 9(3), 249-265. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19378629.2017.1408631

Riley, D. M., & Lambrinidou, Y. (2015). Canons against Cannons? Social justice and the engineering ethics imaginary. Paper presented at the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference and Exposition, Seattle.

Riley, D. M., & Pawley, A. L. (2011). Complicating difference: Exploring and exploding three myths of gender and race in engineering education. Paper presented at the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference and Exposition, Vancouver, BC.

Riley, D. M., Slaton, A. E., & Herkert, J. R. (2015a). What is gained by articulating non-canonical engineering ethics canons? Paper presented at the ASEE Annual Conference & Expositio, Seattle, WA.

Riley, D. M., Slaton, A. E., & Pawley, A. L. (2015b). Social justice and inclusion: Women and minorities in engineering. In A. Johri & B. M. Olds (Eds.), Cambridge Handbook of Engineering Education Research (pp. 335-356). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roncin, A. (2013). Thoughts on engineering ethics education in Canada. Paper presented at the Canadian Engineering Education Association Conference, Montreal, QC.

Roncin, A. (2014). Rationale and teaching objectives for a Canadian engineering ethics game. Paper presented at the Candian Engineering Education Association Conference, Canmore, AB.

Roth, W.-M. (2010). Activism: A category for theorizing learning. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 10(3), 278-291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14926156.2010.504493

Russell, J. S. (2008). Engineering professional growth and quality and cultivating the next generation. Leadership and Management in Engineering, 8(2), 57-60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1532-6748(2008)8:2(57)

Sen, A. (1973). On Economic Inequality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Seron, C. S., Cech, E. A., Silbey, S. S., & Rubineau, B. (2011). "I am not a feminist, but:" Making meanings of being a woman in engineering. Paper presented at the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference and Exposition, Vancouver, BC.

Seron, C., Silbey, S. S., Cech, E., & Rubineau, B. (2016). Persistance is cultural: Professional socialization and the reproduction of sex segregation. Work and Occupations, 43(2), 178-214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888415618728

Slaton, A. E. (2012). The tyranny of outcomes: The social origins and impacts of educational standards in American engineering. Paper presented at the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference & Exposition, San Antonio, TX.

Snyder, B. R. (1970). The Hidden Curriculum. New York: Knopf.

Swan, C.W., Kulich, A., & Wallace, R. (2019). A review of ethics cases: Gaps in the engineering curriculum. Paper presented at the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference & Exposition, Tampa, FL.

Tang, X., & Nieusma, D. (2015). Institutionalizing ethics: Historical debates surrounding IEEE’s 1974 Code of Ethics. Paper presented at the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference and Exposition, Seattle, WA.

Tonso, K. L. (2006a). Student engineers and engineer identity: Campus engineer identities as figured world. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 1(2), 273-307. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-005-9009-2

Tonso, K. L. (2006b). Teams that work: Campus culture, engineer identity, and social interactions. Journal of Engineering Education, 95(1), 25-37.

Tonso, K. L. (2009). Violent masculinities as tropes for school shooters: The Montreal Massacre, the Columbine Attack, and Rethinking Schools. American Behavioral Scientist, 52(9), 1266-1285. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764209332545

Vallero, D. A. (2008). Macroethics and engineering leadership. Leadership and Management in Engineering, 8(4), 287-296.

Vesilind, P. A. (1995). Evolution of the American Society of Civil Engineers code of ethics. Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice, 121(1), 4-10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1052-3928(1995)121:1(4)

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in Society. London: Harvard University Press.

Warford, E. (2016). Ethics in the classroom: The Volkswagen diesel scandal. Paper presented at the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference & Exposition, New Orleans, LA.

Yarmus, J. J. (2010). Ethics in professional engineering: Leadership through integrity. Leadership and Management in Engineering, 10(1), 1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)LM.1943-5630.0000045

Acknowledgements

We could not have done this work without support from the Dean’s Engineering Instructional Innovation Program (EIIP) Fund at the University of Toronto. We also appreciate the involvement of interview participants, engineering professors who invited us into their classes and undergraduate engineering students who participated in our ethics and equity case study workshop.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rottmann, C., Reeve, D. Equity as Rebar: Bridging the Micro/Macro Divide in Engineering Ethics Education. Can. J. Sci. Math. Techn. Educ. 20, 146–165 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42330-019-00073-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42330-019-00073-7