Abstract

Women with a BRCA mutation have an increased risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer. Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the only effective strategy to reduce this risk. Risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) is recommended between the ages of 35 and 40 for women carriers of BRCA1 and between the ages of 40 and 45 for women carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Most women undergo this procedure prior to their natural menopause subsequently developing an anticipated lack of hormones. This condition affects the quality of life and longevity, while it is more pronounced in women carrying a BRCA1 mutation compared to BRCA2 because they are likely to have surgery earlier. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is the only strategy able to significantly compensate for the loss of ovarian hormone production and counteract menopausal symptoms. There is strong evidence that short-term HRT use does not increase the risk of breast cancer among women with a BRCA1 mutation. Few data are available on BRCA2 mutation carriers. Therefore, BRCA mutation carriers require careful counseling about the outcomes of their RRSO, including menopausal symptoms and/or the fear associated with HRT use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Women with BRCA1-2 mutations have an approximately 17–44% risk of ovarian cancer (OC) and a 65–72% risk of breast cancer (BC) [1, 2]. For this reason, risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) represents the main effective prophylactic ovarian cancer risk procedure that should be proposed to BRCA mutation carriers. In fact, RRSO is associated with a reduction in ovarian cancer incidence of up to 96% and in breast cancer incidence up to 50% [3, 4]. Interestingly, the risk reduction in breast cancer-specific mortality is more pronounced for BRCA1-mutated women (HR 0.45, p < 0.0001) as compared to those who are BRCA2-mutated (HR 0.88, p = 0.75) [5].

According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, in order to reduce the risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer, RRSO is recommended after completion of childbearing between the ages of 35 and 40 years for women with BRCA1 mutations and between 40 and 45 years for women with BRCA2 mutations. Approximately 65% of women carrying a BRCA1 mutation will have RRSO prior to their natural menopause, experiencing an earlier onset of surgically induced menopause [6]. In the overall population, menopause occurs at a median age of 52, with the onset of menopause at an age younger or equal to 40 years being defined as premature ovarian failure. Although surgery is possible, RRSO has several short- and long-term clinical consequences. One of them, early menopause, has a serious impact on women’s health because the lack of hormones that characterize this state affects a number of body systems and may impact upon quality of life, such as sexual quality of life and sexual activity, while also being linked to cardiovascular disease, accelerated osteoporosis, and reduced longevity.

For this reason, according to the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) guidelines [7], women with early menopause should receive hormonal replacement therapy (HRT) at the time of diagnosis, and the therapy should be continued until the age of natural menopause.

Review

It is therefore clear that HRT can prevent menopausal symptoms and cardiovascular diseases, osteoporosis, and long-term morbidity associated with hormone depletion.

The chief menopausal symptoms affecting more than 80% of women are hot flashes, which typically result in significant impairment of the quality of life. However, menopause also negatively affects sexual function, with, in fact, 43–50% of women reporting low sexual desire, 50% vaginal dryness, and 17–42% painful sex [8]. Other characteristic symptoms of menopause include neurological dysfunction and cognitive impairment. Moreover, early menopause has a negative effect on bone mineral density and structure, leading to an increased risk for bone fractures [9]. In order to prevent these adverse effects, ESHRE recommends HRT in women with premature ovarian failure. However, this treatment should be accompanied by adherence to positive lifestyle habits, such as regular physical activity, a balanced diet, and cessation of smoking [7]. The prescription of exogenous hormone has also been observed to have a favorable effect in healthy BRCA mutation carriers who underwent RRSO before natural menopause [10].

Because of the increased risk of BC in BRCA mutation carriers, the role of HRT is still controversial based on published data concerning a number of HRT trials carried out in the general population. First, the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trial showed a significant increase in BC among post-menopause women who received estrogen combined with progestins [11]. Importantly, the Million Women Study (MWS) had 1 year previously reported the same findings of the aforementioned trial [12]. However, the above studies were found to be flawed given that the eligible populations recruited in these trials were mainly post-menopausal women who received long-term exposure to hormones after menopause. This differs completely from the case of BRCA-mutated women who have early menopause due to undergoing RRSO. BRCA mutation carriers are typically younger women than those enrolled in the two published trials and have experienced menopausal symptoms prematurely.

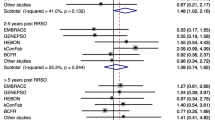

Based on the available data, the short-term use of HRT does not have any impact on the positive effect of RRSO concerning BC risk [13, 14]. A prospective study showed that the use of HRT after RRSO in BRCA1 mutation carriers did not increase the incidence of BC [15]. This study found a possible protective effect on BC in BRCA mutation carriers who used only estrogens. In fact, the authors found an 8% reduction in BC risk (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.83–1.01) for every year of estrogen replacement and an 8% increase in BC risk (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.92–1.27) for every year of progestin replacement. However, these findings did not reach statistical significance. In the same study, a subgroup analysis including women undergoing RRSO before age 45 was also conducted: the authors observed a significant 18% reduction in BC risk for every year of estrogen replacement and a non-significant increase in BC risk of 14% for every year of combined estrogen-progestin replacement therapy. A recent meta-analysis [16] which included a total of three studies, two prospective and one retrospective (13–15), concluded that BC risk associated with HRT was similar for the entire population, with no negative impact being recorded in BRCA mutation carriers who used HRT (HR = 0.98; 95% CI 0.63–1.52). A subgroup analysis was also conducted which showed no significant differences in BC risk between women who used estrogen alone and women who used estrogen plus progesterone. However, a positive though non-significant trend for lower BC risk was observed in those who received estrogen alone compared to those who received estrogen and progesterone. Although it was proposed that hysterectomy can be performed at the same time as RRSO, it has been demonstrated that the use of unopposed estrogen without hysterectomy is related to an increased risk of endometrial cancer (EC) [17]. Furthermore, RRSO is not recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines 2020 [18]. On the other hand, a recent study showed an increased risk of aggressive EC, including uterine serous carcinoma, in BRCA1 women undergoing RRSO without concurrent hysterectomy [19,20,21], while another reported an increased risk of EC with the use of estrogen and progesterone as HRT among women with BRCA1 mutations [22,23,24,25,26]. For these reasons, we believe that the present findings and those regarding the morbidity associated with hysterectomy should be discussed with the patient during the decision-making process [27,28,29].

For BRCA 2 mutation carriers, there are fewer data available on the use of HRT [30,31,32]. However, in these patients, the use of HRT is probably less problematic because of the later age at which they usually undergo the surgery and given their propensity to develop hormone receptor-positive BC [31]. Nevertheless, in this group of patients, the use of HRT should be done cautiously. In conclusion, women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations have an increased risk of developing OC and BC throughout their life compared to the general population [33]. For this reason, patients with a BRCA mutation should undergo RRSO in order to decrease their cancer risk. The downside is that RRSO will result in an earlier menopause among these women, generating negative impacts on quality of life and longevity. In sum, HRT is the only treatment that significantly compensates loss of hormone production and relieves the symptoms of menopause [34].

Within the framework of the decision-making process, BRCA1 mutation carriers should be reassured that short-term use of HRT in no way diminishes the BC risk reduction gained from RRSO. For those women who receive a concomitant hysterectomy, HRT with estrogen alone seems to be the safest and most reasonable choice [25, 35]. Data regarding BRCA1 are few, and hence, more caution is needed in the use of HRT in this group of patients. Studies with large prospective and randomized cohorts are necessary, while future research studies should also evaluate the role of hysterectomy as risk-reducing surgery in BRCA mutation carriers.

This review of the literature sought to underline the fact that when a woman is a healthy carrier of a pathogenetic variant of BRCA1/BRCA2, this does not constitute a contraindication to hormonal contraception and menopausal hormone therapy [32, 33]. Unfortunately, knowledge on the subject is currently limited among both clinicians and patients [25, 34, 35]. This was clearly demonstrated by a recent Italian national survey which revealed that after the diagnosis of healthy carriers, only 24.5% used hormonal contraception and 28.4% used therapy for menopause, even though not going on the therapy reduced those women’s quality of life and the majority of women were dissatisfied with the advice received [36]. Furthermore, 58.2% were unaware of the protective effect of hormonal contraception on ovarian cancer risk [37]. The need for clarity is therefore obvious, both on the part of the population and on the part of health professionals. The current review can represent a first step towards clarifying the issue reporting as it does the most up-to-date data [38]. In conclusion, we believe that truly well-informed physicians alone are able to provide all the available and most recent information on the use of HRT in women with BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations during RRSO decision-making.

Data Availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- RRBSO:

-

Risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

- HRT:

-

Hormone replacement therapy

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- BC:

-

Breast cancer

- RRSO:

-

Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy

- NCCN:

-

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- WHI:

-

Women’s Health Initiative

- ESHRE:

-

European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology

- MWS:

-

Million Women Study

- EC:

-

Endometrial cancer

- OC:

-

Ovarian cancer

References

Massarotti C, Buonomo B, Dellino B, Campanella M, De Stefano C, Ferrari A, Anserini P, Lambertini M, Peccatori FA (2022) Contraception and hormone replacement therapy inhealthy carriers of germline BRCA1/2 genes pathogenic variants: results from an Italian survey. Cancers (Basel) 19:205. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14143457

Kuchenbaecker KB, Hopper JL, Barnes DR, Phillips KA, Mooij TM, Roos-Blom MJ, Jervis S, van Leeuwen FE, Milne RL, Andrieu N, Goldgar DE, Terry MB, Rookus MA, Easton DF, Antoniou AC, McGuffog L, Evans DG, Barrowdale D, Frost D, Adlard J, Ong KR, Izatt L, Tischkowitz M, Eeles R, Davidson R, Hodgson S, Ellis S, Nogues C, Lasset C, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Fricker JP, Faivre L, Berthet P, Hooning MJ, van der Kolk LE, Kets CM, Adank MA, John EM, Chung WK, Andrulis IL, Southey M, Daly MB, Buys SS, Osorio A, Engel C, Kast K, Schmutzler RK, Caldes T, Jakubowska A, Simard J, Friedlander ML, McLachlan SA, Machackova E, Foretova L, Tan YY, Singer CF, Olah E, Gerdes AM, Arver B, Olsson H, Brca BC Consortium (2017) Risks of breast, ovarian, and contralateral breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. JAMA 317:2402–2416. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.7112

Marchetti C, De Felice F, Palaia I, Perniola G, Musella A, Musio D, Muzii L, Tombolini V, Panici PB (2014) Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy: a meta-analysis on impact on ovarian cancer risk and all cause mortality in BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutation carriers. BMC Womens Health 14:150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-014-0150-5

Rebbeck TR, Levin AM, Eisen A, Snyder C, Watson P, Cannon-Albright L, Isaacs C, Olopade O, Garber JE, Godwin AK, Daly MB, Narod SA, Neuhausen SL, Lynch HT, Weber BL (1999) Breast cancer risk after bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 91:1475–1479. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/91.17.1475

Eleje GU, Eke AC, Ezebialu IU, Ikechebelu JI, Ugwu EO, Okonkwo OO(2018) Risk‐reducing bilateral salpingooophorectomy in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 8:CD012464. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012464.pub2

Kotsopoulos J, Gronwald J, Karlan BY, Huzarski T, Tung N, Moller P, Armel S, Lynch HT, Senter L, Eisen A (2018) Hormone replacement therapy after oophorectomy and breast cancer risk among BRCA1 mutation carriers. JAMA Oncol 4:1059–1065

Webber L, Davies M, Anderson R, Bartlett J, Braat D, Cartwright B, Cifkova R, de Muinck Keizer-Schrama S, Hogervorst E, Janse F, Liao L, Vlaisavljevic V, Zillikens C, Vermeulen N, European Society for Human R, POI Embryology Guideline Group on (2016) ESHRE guideline: management of women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum Reprod 31:926–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dew027

Pacello P, Yela D, Rabelo S, Giraldo P, Benetti-Pinto C (2014) Dyspareunia and lubrication in premature ovarian failure using hormonal therapy and vaginal health. Climacteric 17:342–347

Manolagas SC, O’brien CA, Almeida M (2013) The role of estrogen and androgen receptors in bone health and disease. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 9:699

Madalinska JB, van Beurden M, Bleiker EM, Valdimarsdottir HB, Hollenstein J, Massuger LF, Gaarenstroom KN, Mourits MJ, Verheijen RH, van Dorst EB, van der Putten H, van der Velden K, Boonstra H, Aaronson NK (2006) The impact of hormone replacement therapy on menopausal symptoms in younger high-risk women after prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy. J Clin Oncol 24:3576–3582. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1896

Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black H, Bonds D, Brunner R, Brzyski R, Caan B, Chlebowski R, Curb D, Gass M, Hays J, Heiss G, Hendrix S, Howard BV, Hsia J, Hubbell A, Jackson R, Johnson KC, Judd H, Kotchen JM, Kuller L, LaCroix AZ, Lane D, Langer RD, Lasser N, Lewis CE, Manson J, Margolis K, Ockene J, O’Sullivan MJ, Phillips L, Prentice RL, Ritenbaugh C, Robbins J, Rossouw JE, Sarto G, Stefanick ML, Van Horn L, Wactawski-Wende J, Wallace R, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Women’s Health Initiative Steering C (2004) Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 291:1701–1712. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.14.1701

Beral V, C Million Women Study (2003) Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet 362:419–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14065-2

Gabriel C, Tigges-Cardwell J, Stopfer J, Erlichman J, Nathanson K, Domchek S (2009) Use of total abdominal hysterectomy and hormone replacement therapy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. Fam Cancer 8:23–28

Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Wagner T, Lynch HT, Garber JE, Daly MB, Isaacs C, Olopade OI, Neuhausen SL, Eeles R (2005) Effect of short-term hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer risk reduction after bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE Study Group. J Clin Oncol 23:7804–7810

Buonomo B, Massarotti C, Dellino M, Anserini P, Ferrari A, Campanella M, Magnotti M, De Stefano C, Peccatori FA, Lambertini M (2021) Reproductive issues in carriers of germline pathogenic variants in the BRCA1/2 genes: an expert meeting. BMC Med 19:205. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-021-02081-7

Marchetti C, De Felice F, Boccia S, Sassu C, Di Donato V, Perniola G, Palaia I, Monti M, Muzii L, Tombolini V, Benedetti Panici P (2018) Hormone replacement therapy after prophylactic risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy and breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: a meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 132:111–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.09.018

Grady D, Gebretsadik T, Kerlikowske K, Ernster V, Petitti D (1995) Hormone replacement therapy and endometrial cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 85:304–313

Lawton FG, Pavlik EJ (2022) Perspectives on Ovarian Cancer 1809 to 2022 and Beyond. Diagnostics 12:791

Shu CA, Pike MC, Jotwani AR, Friebel TM, Soslow RA, Levine DA, Nathanson KL, Konner JA, Arnold AG, Bogomolniy F (2016) Uterine cancer after risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy without hysterectomy in women with BRCA mutations. JAMA Oncol 2:1434–1440

Segev Y, Rosen B, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, Lynch HT, Moller P, Kim-Sing C, Ghadirian P, Karlan B, Eng C (2015) Risk factors for endometrial cancer among women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: a case control study. Fam Cancer 14:383–391

Bafunno D, Romito F, Lagattolla F, Delvino VA, Minoia C, Loseto G, Dellino M, Guarini A, Catino A, Montrone M, Longo V, Pizzutilo P, Galetta D, Giotta F, Latorre AC, Russo A, Lorusso V, Cormio C (2021) Psychological well-being in cancer outpatients during COVID-19. J BUON 26:1127–1134

Vasta FM, Dellino M, Bergamini A, Gargano G, Paradiso A, Loizzi V, Bocciolone L, Silvestris E, Petrone M, Cormio G, Mangili G (2020) Reproductive outcomes and fertility preservation strategies in women with malignant ovarian germ cell tumors after fertility sparing surgery. Biomedicines 8:554. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines8120554

Daniele A, Divella R, Pilato B, Tommasi S, Pasanisi P, Patruno M, Digennaro M, Minoia C, Dellino M, Pisconti S, Casamassima P, Savino E, Paradiso AV (2021) Can harmful lifestyle, obesity and weight changes increase the risk of breast cancer in BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutation carriers? A mini review. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 19:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-021-00199-6

Vimercati A, Dellino M, Crupano FM, Gargano G, Cicinelli E (2022) Ultrasonic assessment of cesarean section scar to vesicovaginal fold distance: an instrument to estimate pre-labor uterine rupture risk. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 35:4370–4374. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1849121

Daniele A, A Guarini, S Summa, M Dellino, G Lerario, S Ciavarella, P Ditonno, AV Paradiso, R Divella, P Casamassima, E Savino, MD Carbonara, and C Minoia (2021) Body composition change, unhealthy lifestyles and steroid treatment as predictor of metabolic risk in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma survivors. J Pers Med 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11030215

Dellino M, Carriero C, Silvestris E, Capursi T, Paradiso A, Cormio G (2020) Primary vaginal carcinoma arising on cystocele mimicking vulvar cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 42:1543–1545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2020.03.007

Dellino M, E Cascardi, C Leoni, F Fortunato, A Fusco, R Tinelli, G Cazzato, S Scacco, A Gnoni, A Scilimati, V Loizzi, A Malvasi, A Sapino, V Pinto, E Cicinelli, G Di Vagno, G Cormio, V Chiantera, and AS Lagana (2022) Effects of oral supplementation with myo-inositol and D-chiro-Inositol on ovarian functions in female long-term survivors of lymphoma: results from a prospective case-control analysis. J Pers Med 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12091536

Cascardi E, G Cazzato, A Daniele, E Silvestris, G Cormio, G Di Vagno, A Malvasi, V Loizzi, S Scacco, V Pinto, E Cicinelli, E Maiorano, G Ingravallo, L Resta, C Minoia, and M Dellino (2022) Association between cervical microbiota and HPV: could this be the key to complete cervical cancer eradication? Biology (Basel) 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11081114

Dellino M, E Cascardi, M Vinciguerra, B Lamanna, A Malvasi, S Scacco, S Acquaviva, V Pinto, G Di Vagno, G Cormio, R De Luca, M Lafranceschina, G Cazzato, G Ingravallo, E Maiorano, L Resta, A Daniele, and D La Forgia (2022) Nutrition as personalized medicine against SARS-CoV-2 infections: clinical and oncological options with a specific female groups overview. Int J Mol Sci 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23169136

Silvestris E, Cormio G, Skrypets T, Dellino M, Paradiso AV, Guarini A, Minoia C (2020) Novel aspects on gonadotoxicity and fertility preservation in lymphoproliferative neoplasms. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 151:102981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.102981

Silvestris E, S D'Oronzo, P Cafforio, A Kardhashi, M Dellino, and G Cormio (2019) In vitro generation of oocytes from ovarian stem cells (OSCs): in search of major evidence. Int J Mol Sci 20.https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20246225

Dellino M, Silvestris E, Loizzi V, Paradiso A, Loiacono R, Minoia C, Daniele A, Cormio G (2020) Germinal ovarian tumors in reproductive age women: fertility-sparing and outcome. Medicine (Baltimore) 99:e22146. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000022146

Silvestris E, Dellino M, Cafforio P, Paradiso AV, Cormio G, D’Oronzo S (2020) Breast cancer: an update on treatment-related infertility. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 146:647–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-020-03136-7

Bergamini A, Luisa FM, Dellino M, Erica S, Loizzi V, Bocciolone L, Rabaiotti E, Cioffi R, Sabetta G, Cormio G, Mangili G (2022) Fertility sparing surgery in sex-cord stromal tumors: oncological and reproductive outcomes. Int J Gynecol Cancer 32:1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1136/ijgc-2021-003241

Viviani S, Dellino M, Ramadan S, Peracchio C, Marcheselli L, Minoia C, Guarini A (2022) Fertility preservation strategies for patients with lymphoma: a real-world practice survey among Fondazione Italiana Linfomi centers. Tumori 108:572–577. https://doi.org/10.1177/03008916211040556

Silvestris E, G De Palma, S Canosa, S Palini, M Dellino, A Revelli, and AV Paradiso (2020) Human ovarian cortex biobanking: a fascinating resource for fertility preservation in cancer. Int J Mol Sci 21.https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21093245

Casaubon JT, Kashyap S, Regan JP (2022) BRCA 1 and 2, in StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL)

Najjar S, Allison KH (2022) Updates on breast biomarkers. Virchows Arch 480:163–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-022-03267-x

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The manuscript had ethical approval. The Ethical Review Board was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Policlinico Bari, Italy, who approved the study protocol.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Loizzi, V., Dellino, M., Cerbone, M. et al. Hormone replacement therapy in BRCA mutation carriers: how shall we do no harm?. Hormones 22, 19–23 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42000-022-00427-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42000-022-00427-1