Abstract

Introduction

OSA has been postulated to be associated with mortality in COVID-19, but studies are lacking thereof. This study was done to estimate the prevalence of OSA in patients with COVID-19 using various screening questionnaires and to assess effect of OSA on outcome of disease.

Methodology

In this prospective observational study, consecutive patients with RT-PCR confirmed COVID-19 were screened for OSA by different questionnaires (STOPBANG, Berlin Questionnaire, NoSAS, and Epworth Scale). Association between OSA, outcome (mortality) and requirement for respiratory support was assessed.

Results

In study of 213 patients; screening questionnaires for OSA [STOPBANG, Berlin Questionnaire (BQ), NoSAS] were more likely to be positive in patients who died compared to patients who survived. On binary logistic regression analysis, age ≥ 55 and STOPBANG score ≥ 5 were found to have small positive but independent effect on mortality even after adjusting for other variables. Proportion of patients who were classified as high risk for OSA by various OSA screening tools significantly increased with increasing respiratory support (p < 0.001 for STOPBANG, BQ, ESS and p = 0.004 for NoSAS).

Conclusion

This is one of the first prospective studies of sequentially hospitalized patients with confirmed COVID-19 status who were screened for possible OSA could be an independent risk factor for poor outcome in patients with COVID-19.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The beginning of 2020 saw the evolution of COVID-19 into a global pandemic. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was discovered in December 2019 and is responsible for the causation of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [1]. As of February 3rd 2021, over 100 million cases of COVID-19 have been registered around the world resulting in 2,264,968 deaths [2]. As the world struggles to cope with this pandemic, researchers across the world are curetting mechanistic pathways that would possibly explain the disease severity in certain population.

Mortality in COVID-19 disease was mainly seen in the subgroup of patients who developed severe respiratory failure owing to acute interstitial pneumonia involving both lungs and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [3].While the understanding of pathogenesis is still a topic of research, few studies have pointed clinical association between mortality and older age, male sex, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases [4,5,6]. Interestingly obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is also commonly associated with these similar comorbidities [7, 8].

OSA is a pro-inflammatory state involving mediators like IL-6, TNF-alpha, MCP-1, etc. [9]. IL-6 levels have also got prognostic implications in COVID-19 disease indicating that OSA might lead to worsening hypoxemia and cytokine storm. Furthermore, it has been hypothesized that SARS-CoV-2 infects humans through ACE-2 receptor which again has increased expression in obese OSA patients [10]. Obesity causes impaired respiratory mechanics leading to decreased FEV1, FVC, diaphragmatic excursion which in turn worsens outcome in patients with respiratory failure [11]. OSA can cause hypoxemia leading to poorer outcome in patients of COVID-19 pneumonia.

In accordance with these facts, it was observed that almost one-third of the COVID-19 cases requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission had pre-existent OSA [12]. Similarly in two small studies on patients of severe COVID-19 pneumonia it was observed that one-quarter of the patients were known case of OSA [13, 14].

Since OSA and patients developing COVID-19 ARDS have so much in common, it is worthwhile to look into the association between these two. Thus, we need prospective studies to see whether people with OSA are at greater risk to develop COVID-19 related complications. Association, if any will further help in early triaging of complication prone population and possibly in prevention of complications. This study was planned to estimate the proportion of COVID-19 patients who have OSA based on various standard screening questionnaires and to explore if there is any association of being at high risk for OSA and severity of COVID-19 including mortality.

2 Methods

2.1 Setting and Design

This was a single center prospective observational study done at All India Institute of Medical Sciences Bhopal, India between 10th August and 22nd September 2020 on consecutive COVID-19 positive patients admitted to intensive care as well as isolation wards of hospital.

2.2 Participants and Procedures

All consecutive patients with confirmed positive report of COVID-19 RT-PCR on nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab were enrolled. Patients were either admitted to intensive care or isolation wards as per clinical decision. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows.

2.2.1 Inclusion Criteria

-

1.

Patients positive for COVID-19 by RT-PCR of nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab.

-

2.

Age > 18 years.

-

3.

Patients whose spouse or bed partner was willing for confirmation of history and sleeping pattern.

-

4.

Patients and attendants who gave written informed consent for participating in study.

2.2.2 Exclusion Criteria

-

1.

Patients/attendants who refused to cooperate or to give written informed consent.

-

2.

Sleeping partner not available to confirm history given by patient.

-

3.

Patient who were already intubated and were on mechanical ventilation.

-

4.

Patients who were not in a state to answer questions.

-

5.

Any recent surgery in last one month.

After obtaining informed consent from patient or bed partner of patient, demographic details, medical history including comorbidities were noted at the time of admission. As general practice, height and weight is measured for all patients in our ICU and ward at the time of admission. BMI was calculated according to other recorded weight and height data. Height and weight were measured using Seca®213 portable stadiometer and Seca®803 electronic flat scale, respectively. Neck circumference was measured at the level of cricothyroid membrane in sitting position using girth measuring tape.

Patients were asked for NOSAS [15], STOP BANG [16], BERLIN [17], and Epworth sleepiness scores [18] within one day of admission. History given by patient was reconfirmed by the bed partner of same patient.

NoSAS score category was classified as probable OSA if score was ≥ 8. STOP BANG was classified further as high risk of OSA for score ≥ 5. Berlin score was calculated in all three categories and classified into high risk if there were two or more categories with score ≥ 2 and low risk if there was only one category or no category where score was ≥ 2. ESS scores ≥ 10 was used to classify ESS into high or low risk categories for daytime sleepiness.

Patients were observed for their maximum oxygen and ventilatory requirement during their stay in hospital and were further divided into four groups as follows:

-

1.

‘No oxygen’ group: patients who did not require oxygen during their hospital stay.

-

2.

‘Oxygen only’ group: patients who required oxygen through facemask, venturi mask or nasal prongs and their fraction of oxygen requirement was less than 0.5. These patients never required invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) or non-invasive ventilation (NIV) or high flow nasal cannula (HFNC) during their hospital stay.

-

3.

‘NIV’ group: patients who required either NIV or HFNC anytime during their stay. These patients were never intubated during their hospital stay.

-

4.

‘IMV’ group: patients who were intubated.

Patients were followed up for a period of 28 days after discharge or death during that period.

2.3 Data Analysis

We have used R software version 3.6.1 with gtsummary, ggplot2, and finalfit packages for data analysis [19,20,21,22]. Nominal variables are summarized as count and percentages while numerical variables as mean and standard deviation. Proportion of patients with high risk for OSA as defined by different questionnaires were analyzed and compared for baseline characteristics, types of respiratory or ventilatory requirement and mortality. Difference in distribution of nominal variables across groups was tested by chi-squared test and in numerical variables by Wilcoxon rank sum test. Logistic regression models were fitted separately to estimate effect age, gender, neck circumference, history of diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and STOP BANG score categories. Then to multivariable logistic regression model was fitted to test effect of variables which had p < 0.25 in univariable analysis. Model assumptions and goodness-of-fit was also tested by standard procedures.

2.4 Ethics and Permissions

Institutional Human Ethics Committee of AIIMS Bhopal reviewed and approved study protocol with approval letter number IHEC-LOP/2020/IM0309. Eligible patients and attendants were provided participant information sheet in native language for explaining purpose of study, procedures, and expectations from participants.

3 Results

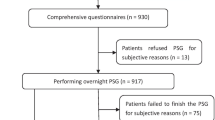

During the study period, 250 patients with RT-PCR positive for COVID-19 got admitted in our hospital (Fig. 1). After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 213 patients (144 male and 69 female) were finally enrolled and were prospectively followed till final outcome (28 days post-discharge/death). Out of 213 patients, 57 succumbed to COVID-19 ARDS (Table 1). Patients who died were elderly (p < 0.001) and were more likely to have hypertension (p = 0.007) and/or Diabetes mellitus (p = 0.001). Screening questionnaires for OSA [STOPBANG, Berlin Questionnaire (BQ), NoSAS] were more likely to be positive in patients who died compared to patients who survived. Similarly, Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS) score was significantly higher in deceased group {12 (9.0–13.0) v/s 9.0 (5.2–11.0)} (p < 0.001).

Similar findings were seen when baseline characteristics of 213 patients were compared according to across various modes of respiratory support (without oxygen, oxygen only, NIV group or IMV groups) (Table 2).

Proportion of patients who were classified as high risk for OSA by various OSA screening tools significantly increased with increasing respiratory support (Table 2 and Fig. 2) (p < 0.001 for STOPBANG, BQ, ESS and p = 0.004 for NoSAS).

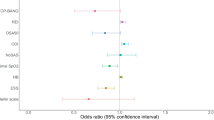

On univariate analysis, age, hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), and OSA were found to be significant. Since median age was 55 years in our sample, so cut off of 55 years was used for multivariate analysis. On multivariate analysis, STOP BANG was used, since it is most commonly used screening tool for OSA screening both from clinical and research point of view. On binary logistics regression analysis, only age ≥ 55 and STOPBANG score ≥ 5 was found to be determinants of mortality.

We fitted a logistic model to predict outcome (mortality) with age group, STOP BANG score, the presence of diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and neck circumference. The model's explanatory power is moderate (Tjur's R2 = 0.14). Within this model, the effect of age group [≥ 55 years] is positive and can be considered as small and significant (beta = 0.74, SE = 0.37, 95% CI [0.04, 1.48]), while the effect of STOP BANG score in high risk group is also positive and can be considered as small and significant (beta = 0.91, SE = 0.42, 95% CI [0.08, 1.74]). The effects observed for older age and higher STOP BANG score were adjusted for neck circumference as well as history of comorbidities. Odds ratio for these variables which are exponentiated coefficients of logistic model are also presented. Odds of mortality were 2.10 (1.04–4.37, p = 0.042) among age more than 55 years compared to those with age less than 55 years. Participants classified in high risk category on STOP BANG score were having odds of 2.48 (1.09–5.69, p = 0.031) for mortality compared to those classified as low to intermediate risk for OSA. (Table 3).

4 Discussion

This is one of the first prospective studies of sequentially hospitalized patients with confirmed COVID-19 status who were screened for possible OSA in a questionnaire-based format. This study shows that OSA could be an independent risk factor for poor outcome in patients with COVID-19.

Studies have highlighted association of severity of COVID-19 with older age, obesity, male sex, and comorbidities like DM, HTN, Coronary Artery Disease, and Chronic Kidney Disease [4]. Few researchers have observed a possible association with obstructive sleep apnea retrospectively. Cade et al. analyzed electronic health record data and observed 443 of 4668 participants with sleep apnea had increased mortality rate of 11.7% as compared to controls (6.9%) with an odds ratio of 1.79 [23]. In a study involving 700 patients, 124 had pre-diagnosed OSA; of all the patients requiring ICU care, 29% patients had pre-existent OSA in the same study [12]. Two small case series focusing critically ill patients of COVID-19 had shown 20–25% patients having OSA [13, 14]. In the CORONADO study, 144/1189 patients were already known case of OSA. They have also found OSA to be independent risk factor for poor outcome in COVID-19 related illness [24].

Age and neck circumference are integral component of most OSA screening questionnaire (STOPBANG and NoSAS) and the presence of hypertension is included as question in STOPBANG and Berlin Questionnaire. Thus, multivariate analysis was done to find independent association of OSA with mortality. In-fact in our study, only age and OSA were found to be significant factor for mortality in multivariate analysis. This was in contrast to most of previous studies, in which HTN & DM were found to be important factors for mortality.

Cardiac morbidity in COVID patients seems to be high and could prove fatal. Cardiac complications in SARS-CoV 2 infection includes myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, venous thromboembolism, and arrythmias [25, 28] which might get accentuated in the presence of OSA. OSA leads to a procoagulant state and increased risk of DVT and PE. DVT and PE are known risk factors for mortality in COVID-19 [26]. The presence of procoagulant state is a breeding ground for COVID related coagulopathy. OSA has been associated with obesity, HTN, DM, CAD, arrythmia, chronic kidney disease, dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome, and pulmonary embolism [27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. All these factors were almost consistently associated with poor prognosis in patients with COVID-19 in various studies [34, 35].

STOPBANG, BQ, and NoSAS have comparable sensitivity and specificity to polysomnography (PSG) for the diagnosis of OSA [15, 36, 37]. In our study, it was shown that patients with higher respiratory requirements had significantly higher probability of having OSA and this was consistently seen in all questionnaires for increasing severity of respiratory support.

Strength of this study is that screening tools were asked to both patients and sleeping partner. It is known fact that questions like history of apnea and history of snoring are more reliably answered by patients sleeping partner rather than patients. So, if there was any discrepancy in the answers for apnea or snoring, then answer from sleeping partner was considered final. Those patients who were not in a state to answer questions were excluded from our study. Second, we screened for OSA using multiple questionnaires. Most importantly, this is the first study in which patients being admitted for COVID-19 were screened for OSA by different questionnaires. All previous studies on possible association between OSA and COVID-19 related ARDS were done in already diagnosed cases of OSA.

Important limitations were: (1) It was a single center study conducted at a tertiary care hospital where relatively more sick patients were admitted. This poses possibility of selection bias and, therefore, results of the study should be interpreted in this context and not be generalized to all COVID-19 patients. (2) Our diagnosis of OSA was based on screening questionnaires and gold standard PSG could not be done for confirmation of OSA. However, we have evaluated risk for OSA by multiple questionnaires and results were coherent. (3) We have tried to be precise in our results by limiting to patients whose spouse or bed partner was willing to confirm history and sleeping pattern. Thereby some selection bias may have been encountered. Similarly, excluding patients already intubated leads to similar selection bias as it eliminates the sickest patients. However, we have tried to present our results with greater precision thereby compromising on some selection bias. (4) Our study had limited sample size. The results may not have reflected some common factors associated with poor outcome of COVID-19 as reflected in larger studies.

5 Conclusions

This study shows that OSA might be an independent risk factor for poor outcome in COVID-19 related illness.

Abbreviations

- ACE 2:

-

Angiotensin converting enzyme 2

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BQ:

-

Berlin questionnaire

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- COVID-19:

-

Corona virus disease 2019

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- ESS:

-

Epworth sleepiness scale

- FEV1:

-

Forced expiratory volume in 1st second

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- HDL:

-

High density lipoprotein

- HFNC:

-

High flow nasal cannula

- HTN:

-

Hypertension

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IL-6:

-

Interleukin 6

- IMV:

-

Invasive mechanical ventilation

- LDL:

-

Low density lipoprotein

- MCP 1:

-

Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1

- NIV:

-

Non-invasive ventilation

- NSVT:

-

Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia

- OSA:

-

Obstructive sleep apnea

- PSG:

-

Polysomnography

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- SARS-CoV 2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus 2

- TNF α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor α

References

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–33.

WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard | WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 26]. https://covid19.who.int/.

Marini JJ, Gattinoni L. Management of COVID-19 respiratory distress. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:2329–30.

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Articles clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet. 2020;395:1054–62.

Li X, Xu S, Yu M, Wang K, Tao Y, Zhou Y, et al. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. J Allergy ClinImmunol. 2020;146(1):110–8.

Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, Hardwick HE, Pius R, Norman L, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO clinical characterisation protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;22(369):m1985–m1985.

Saxena K, Kar A, Goyal A. COVID 19 and OSA: exploring multiple cross-ways. Sleep Med [Internet]. 2020 Nov 11 [cited 2021 Jan 1]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7657027/.

Goyal A, Kar A, Saxena K. COVID eyes: REM in COVID-19 survivors. Sleep Vigil. 2021;11:1–3.

Kheirandish-Gozal L, Gozal D. Obstructive sleep apnea and inflammation: proof of concept based on two illustrative cytokines. Int J MolSci. 2019;20(3):459.

Dalan R, Bornstein SR, El-Armouche A, Rodionov RN, Markov A, Wielockx B, et al. The ACE-2 in COVID-19: foe or friend? HormMetab Res. 2020;52(5):257–63.

Abdeyrim A, Zhang Y, Li N, Zhao M, Wang Y, Yao X, et al. Impact of obstructive sleep apnea on lung volumes and mechanical properties of the respiratory system in overweight and obese individuals. BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15(1):76.

Bhatla A, Mayer MM, Adusumalli S, Hyman MC, Oh E, Tierney A, et al. COVID-19 and cardiac arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17(9):1439–44.

Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, Kim R, Jerome KR, Nalla AK, et al. Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region—case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2012–22.

Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, Lokhandwala S, Riedo FX, Chong M, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:1612–4.

Marti-Soler H, Hirotsu C, Marques-Vidal P, Vollenweider P, Waeber G, Preisig M, et al. The NoSAS score for screening of sleep-disordered breathing: a derivation and validation study. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(9):742–8.

Chung F, Subramanyam R, Liao P, Sasaki E, Shapiro C, Sun Y. High STOP-Bang score indicates a high probability of obstructive sleep apnoea. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108(5):768–75.

Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep Apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(7):485–91.

Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–5.

Presentation-Ready Data Summary and Analytic Result Tables [R package gtsummary version 1.3.5]. 2020.

Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics [R package ggplot2 version 3.3.2]. 2020.

Quickly Create Elegant Regression Results Tables and Plots when Modelling [R package finalfit version 1.0.2]. 2020.

R: The R Project for Statistical Computing [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 29]. https://www.r-project.org/.

Cade BE, Dashti HS, Hassan SM, Redline S, Karlson EW. Sleep Apnea and COVID-19 mortality and hospitalization. Am J RespirCrit Care Med. 2020;202(10):1462–4.

Cariou B, Hadjadj S, Wargny M, Pichelin M, Al-Salameh A, Allix I, et al. Phenotypic characteristics and prognosis of inpatients with COVID-19 and diabetes: the CORONADO study. Diabetologia. 2020;63(8):1500–15.

Bandyopadhyay D, Akhtar T, Hajra A, Gupta M, Das A, Chakraborty S, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: cardiovascular complications and future implications. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2020;20:311–24.

Liak C, Fitzpatrick M. Coagulability in obstructive sleep apnea. Can Respir J. 2011;18(6):338–48.

Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:1239–42.

Goyal A, Pakhare AP, Bhatt GC, Choudhary B, Patil R. Association of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea with poor academic performance: a school-based study from India. Lung India. 2018;35(2):132–6.

Goyal A, Pakhare A, Chaudhary P. Nocturic obstructive sleep Apnea as a clinical phenotype of severe disease. Lung India. 2019;36(1):20–7.

Goyal A, Agarwal N, Pakhare A. Barriers to CPAP use in India: an exploratory study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(12):1385–94.

Goyal A, Pakhare A, Tiwari IR, Khurana A, Chaudhary P. Diagnosing obstructive sleep apnea patients with isolated nocturnal hypoventilation and defining obesity hypoventilation syndrome using new European Respiratory Society classification criteria: an Indian perspective. Sleep Med. 2020;1(66):85–91.

Goyal A, Pakhare A, Subhedar R, Khurana A, Chaudhary P. Combination of positional therapy with positive airway pressure for titration in patients with difficult to treat obstructive sleep Apnea. Sleep Breath [Internet]. 2021 Jan 23 [cited 2021 Jan 25].https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-021-02291-6

Chaudhary P, Goyal A, Goel SK, Kumar A, Chaudhary S, KirtiKeshri S, et al. Women with OSA have higher chances of having metabolic syndrome than men: effect of gender on syndrome Z in cross sectional study. Sleep Med. 2021;1(79):83–7.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506.

Hariyanto TI, Kurniawan A. Dyslipidemia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Diabetes MetabSyndr. 2020;14(5):1463–5.

Chiu HY, Chen PY, Chuang LP, Chen NH, Tu YK, Hsieh YJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Berlin questionnaire, STOP-BANG, STOP, and Epworth sleepiness scale in detecting obstructive sleep Apnea: a bivariate meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;36:57–70.

Hong C, Chen R, Qing S, Kuang A, Yang H, Su X, et al. INTRODUCTION validation of the NoSAS score for the screening of sleep-disordered breathing: a hospital-based retrospective study in China. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(2):191–7.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Abhishek Goyal MD, DM had full access of the data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of data analysis. He is the guarantor of the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis. Dr. Avishek Kar and Dr. Khushboo Saxena contributed substantially and equally to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AG: conceptualization, revision of final manuscript for intellectual data, statistical analysis, and interpretation, managed patients. AK: data collection, managed patients, and drafted manuscript. KS: managed patients, data collection, and drafted manuscript. AP: statistical analysis, manuscript preparation, and interpretation of data. AK: managed patients and data collection. SS: managed patients and data collection. PKB: data collection and manuscript preparation. SSKRC: data collection and manuscript preparation. YN: managed patients and data collection.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kar, A., Saxena, K., Goyal, A. et al. Assessment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Association with Severity of COVID-19: A Prospective Observational Study. Sleep Vigilance 5, 111–118 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41782-021-00142-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41782-021-00142-8