Abstract

Telebehavioral health (TBH) in the form of synchronous video is effective, well received and a standard way to practice. Current guidelines and policies discuss the importance of good clinical, technical, and administrative components to care. A review of the TBH evidence-based literature across psychiatry/medicine, psychology, social work, counseling, marriage/family, behavioral analysis, and other behavioral sciences found no common TBH competencies across disciplines. The scope of professional guidelines and standards about technology are broad (e.g., practice of telepsychology; Internet and social media use in social work practice), to mid-range (e.g., American Telemedicine (ATA), American Counseling Association (ACA)), to narrow (e.g., preliminary “guidelines” for asynchronous communication such as e-mail and texts). There is only one set of competencies for telepsychiatry, which discusses skills, training and evaluation. These competencies suggested (1) novice/advanced beginner, competent/proficient, and expert levels; (2) domains of patient care, communications, system-based practice, professionalism, practice-based improvement, knowledge and technological know-how; and (3) pedagogical methods to teach and evaluate skills. Revisions to this framework and technology-specific competencies with additional domains may be needed. A challenge to competencies across disciplines may be finding consensus, due to varying scopes of practice, training differences and faculty development priorities. Disciplines and organizations involved with TBH need to consider certification/accreditation and ensure quality care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Technology is becoming part of our society in a breath-taking fashion, as part of our education, health care, business and social culture. People obtain health information via websites, participate in support groups, use tools for lifestyle change, obtain consultations by a professional, and receive services by video or Internet (Frydman 2010; Hilty et al. 2013a, 2015e). Telebehavioral health (TBH), a term more inclusive of the treatment of addictions, may be preferable to telemental health (TMH), though regulatory boards have used up to 19 terms in referring to TBH (Ostrowski and Collins 2016). A review of TBH best practices revealed that each discipline and field has its own nomenclature for telehealth (e.g., telepsychiatry, telepsychology, distance counseling) (Luxton et al. 2016; Mucic and Hilty 2015).

Current competency-based education (CBE) and training movements began with US efforts to reform teacher education and training in the 1960s (Brown 1994; Tuxworth 1994). CBE focuses on what students know and can do—skills—rather than on what is taught (Ford 2014). A competency may best be described as a measurable human capability required for effective performance (Marrelli et al. 2005) with gradation of levels of proficiency (Brenner 1984). Professional competencies have been suggested in the past for TBH, as in-person and TBH skills may have differences (Maheu et al. 2004; Callan et al. 2016; Luxton et al. 2016). The first set of telecompetencies—in telepsychiatry (TP) in 2015—suggested (1) novice/advanced beginner, competent/proficient, and expert levels; (2) domains of patient care, communications, system-based practice, professionalism, practice-based improvement, knowledge and technology know-how; and (3) pedagogical methods to teach and evaluate skills (Table 1; Hilty et al. 2015c).

Maheu et al. (2004) discussed the Report of the Interdisciplinary Telehealth Standards Working Group (1998), which anticipated changes in standards of professional conduct related to technology:

“Standards of professional conduct are unlikely to change simply as a result of developing telehealth technology. However, the professions will likely need to develop interpretations of their standards of professional conduct as they apply to telehealth, since the application of the standards and the measurement criteria used to assess them may be different in this area. There will be a need for ongoing evaluation by professions of these issues” (pp. xiii-xiv).

This illustrates how competencies dovetail with clinical standards, quality improvement, peer review, and professional associations and regulatory boards (Maheu et al. 2017).

The current paper will focus on the answers to three questions:

-

1)

What is the state of TBH evidence relevant to the development of competencies?

-

2)

Which existing and new frameworks may help with the development of TBH competencies?

-

3)

What are the similarities and differences across disciplines related to TBH competencies?

We hope the asking of these questions, reflection upon them and answers forthcoming will help clinicians self-assess skill, knowledge and attitudes related to TBH. Further reflection on TBH versus in-person care is also suggested and for those interested, obtaining training with feedback for performance improvement may be indicated longitudinally as part of life long learning.

What Is the State of TBH Evidence Relevant to the Development of TBH Competencies?

Clinical Outcomes and Evaluation

TBH services for clients/patients of virtually all ages and many cultures have included clinical assessment; psychological and cognitive testing (Nelson et al. 2013; American Telemedicine Association (ATA) 2009, 2013, 2017); triage; a wide range of psychotherapies (e.g., individual, family/system, group); and psychiatric interventions. Studies show that TBH outcomes are similar to in-person care across populations, ages and disorders (Hilty et al. 2013a, b). More randomized controlled trial research is indicated for specialty populations (e.g., child and adolescent, geriatric and cultures) (Hilty et al. 2015f; Rabinowitz et al. 2010; Hilty et al. 2013a). Client/patient ratings of satisfaction with psychotherapeutic interventions and therapeutic alliance in treatment are comparable between TBH and in-person delivery (Jenkins-Guarnieri et al. 2015) and predict a good therapeutic alliance and therapy outcomes (Horvath et al. 2011).

The evidence-based for psychotherapy and counseling by TBH is growing. The core issues about technology include informed consent; client/patient education; exploring the virtual therapeutic connection (Glueck 2013); and replacing behaviors like handing a tissue box or a handshake with verbal statements conveying empathy (Hilty et al. 2002). One of the first meta-analyses to examine the use of videoconferencing for psychotherapy reviewed therapeutic types/formats, populations served, satisfaction, feasibility, and outcome data (Backhaus et al. 2012). These researchers concluded that TBH is feasible, has been used in a variety of therapeutic formats and with diverse populations, and has similar clinical outcomes to traditional in-person psychotherapy. Guidelines for therapy by videoconferencing have been explored (Nelson et al. 2012, 2013).

An organizing concept of TBH’s impact is effectiveness, defined in Latin as “having the power to produce an effect … a decisive effect; efficient; as, … an effective … remedy” (Hilty et al. 2013a). Ideally, effectiveness should be considered for the client/patient, provider, program, community, and society. In telemedicine and TBH, few authors have discussed effectiveness (Hilty et al. 2003, 2013a); efficacy was the prior emphasis (Richardson et al. 2009). The broad underlying premise of being effective is ensuring that the technology is chosen specific to the objective to achieve or the type of setting and the service to be offered (World Health Organization 2011; Hilty et al. 2013a).

Evaluation of TBH has gone through three phases (Hilty et al. 2013a). First, TBH was found to be effective in terms of increasing access to care, acceptance, and good educational outcomes (Hilty et al. 2013a). Second, it was noted to be valid and reliable compared to in-person services (ATA 2009; Hilty et al. 2013a). Comparison (i.e., “as good as”) and non-inferiority studies of TBH by videoconferencing in-person care show similar outcomes. Third, frameworks are being used to approach complex themes like models and costs (ATA 2009, 2013; Hilty et al. 2015f). The ATA (ATA 2013) produced a lexicon for evaluating specific (e.g., satisfaction; process of care like no-shows, coordination, completion of treatment); costs). The Telebehavioral Health Institute is a clearinghouse for many such statements across behavioral disciplines (TBHI 2017).

Professional association standards and guidelines serve as a shorthand guide to helping the average practitioner understand and/or implement the evidence base within any discipline. They therefore can be quite useful when developing competencies. Those of particular interest to TBH competencies include (1) the ATA’s videoconferencing and Internet-based care guidelines for adults (ATA 2009, 2013) and children and adolescents (ATA 2017). Other noteworthy contributions to competency development include (1) American Psychological Association Guidelines for the Practice of Telepsychology (American Psychological Association 2013); (2) the Provision of Psychological Services via the Internet and Other Non-direct Means (British Psychological Society 2009); (3) the Standards for Technology and Social Work Practice (U.S. National Association of Social Workers 2005, 2017); and (4) the Australian Psychological Society’s guidelines for services provided by the Internet and other technologies (Australian Psychological Society 2011). Technology is also on the radar of the American Association of Marriage and Family Therapists (AAMFT), American Counseling Association (ACA), the American Psychiatric Association and the National Association for Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors (NAADAC; now called, the Association for Addiction Professionals or AAP).

Models of care on a spectrum: evaluation vs. treatment, synchronous (i.e., in-person/video) vs. asynchronous care (i.e., text, app) and resource allocation.

Low, mid and high intensity models for TBH care have been described (Hilty et al. 2015b, f). These are akin to clinical services, care coordination, and team-based care for depression, diabetes and other disorders. The model chosen—which should be discussed as part of informed consent—pre-determines roles, decision-making, reimbursement and other medico-legal requirements. With the advent of technologies and their integration into health care, the possibility of collaborative care (Myers et al. 2015) and digital stepped care are possible (Hilty et al. 2017).

Low intensity models. These may include an evaluation (only), psychological testing and/or other form of one time (or serial) consultation without assuming the treating clinician role. These client/patient services may also include materials for psychoeducation and tips for self-assessment (e.g., diabetes, depression, and self-help and support groups). Mid-intensity options are informal online provider consultation, formal education programs, asynchronous consultation with providers (Yellowlees et al. 2013) and Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (ICBT). High-intensity options include collaborative care or in-person MH services with professionals (Celio et al. 2000; Clarke et al. 2005; Andersson et al. 2006; Christensen et al. 2006; Ritterband and Thorndike 2006; Ljotsson et al. 2007; Mucic et al. 2015).

The e-BH Spectrum: a Broader Range of TBH Services

TBH may be part of a broader spectrum of care—that of e-mental health (e-MH or e-BH) (Hilty et al. 2015b), which has been defined as “mental health services and information delivered or enhanced through the Internet and related technologies” (Christensen et al. 2002). There is no agreement on a field-specific definition, but a meta analysis shows that health behaviors change with e-MH interventions (Laranjo et al. 2015). Systems are also using TBH to increase clinical operating efficiency by integrating care and providing care at multiple points-of-service (Hilty et al. 2015f) and to leverage interdisciplinary team members’ clinical, administrative, and other care coordination expertise (Hilty et al. 2015d). Finally, direct in-person and/or TBH video care may be costly, unavailable to many, and insufficient alone, such that many clients/patients and caregivers are seeking e-health information and e-BH services from non-traditional sources like the Internet.

Maheu et al. (2001) discussed the use of TBH including telephones, computer-assisted self-help, email, chat rooms, and videoconferencing for hospitals, community mental health centers, nursing homes, schools, military, tribal and frontier environments, schools and correctional facilities. A clinical model for clinical care and training related to psychotherapy was included in the first handbook related to psychotherapy with different technologies (Maheu et al. 2004). Overall, these technologies should be evidence-based and be used with an evidence-based approach.

Many patients use mobile technologies like psychiatric/MH/BH apps and they may or may not share this use with a therapist. Purposeful use of apps—one selected to a prioritized treatment goal (e.g., depression rating; Torous et al. 2015) and with data transferred to the therapist—is suggested. Overall, BH apps are used for many functions, including to (1) communicate with other patients, caregivers, social supports, or providers; (2) augment psychotherapy and medical support with journaling, diaries, symptom tracking tools, and psychoeducation between clinic appointments; (3) (smart) monitor, that is, to use tools to predict relapse behavior or worsening affective symptoms, through sensors and data activity; (4) to practice self-assessment and care through reflection about their symptoms; (5) make learning more interactive than traditional paper homework; and (6) organize, track, and thus monitor long-term their activities, moods, and therapy homework (Hilty et al. 2015b). Clients/patients’ logging of symptoms, affect, behavior, and cognitions “in time” is known as ecological momentary assessment (EMA) (Moskowitz and Young 2006).

There are some concerning areas, though, about this e-BH spectrum. Though online health information varies in quality and readability (Nemoto et al. 2007; Ferreira-Lay and Miller 2008; Kalk and Pothier 2008), quality online materials can be used enhances users’ coping, sense of empowerment, and self-efficacy. As above, if a reputable site is “prescribed” by a clinician with a shared purpose, there is greater likelihood for benefit. A key question whether social media and networking is on the e-BH spectrum or not—that is, is it clinical? There is debate on this. On one hand, it theoretically could be a modality that is part of clinical care; on the other hand, it is inherently public and may not be regular monitored by the clinician. Some have noted that professional behaviors and boundaries become less rigid with e-communication (Maheu et al. 2004; American Medical Association 2011), which raises questions and concerns about explicit posts, symptoms of danger (e.g., suicidal ideation), boundary violations, and privacy for many parties, including administrators and clinicians.

With e-BH care complementing in-person care or used instead, providers must contend with slightly different workflows and processes of care. Clinicians have to figure out how to spend the “therapeutic hour” (i.e., regular services versus using some time to review what e-BH options clients/patients are using versus giving them assignments using online resources. Basic questions related to e-BH care and education include:

-

What is the best way to align a technology to meet the specific needs of any given clients/patient?

-

How can clients/patients and providers be empowered, reflect, and weigh the pros and cons of available options in order to learn new behaviors and evaluate outcomes?

-

How can one encourage trainees and other clinicians to learn this spectrum of care and develop skills?

-

How do we ensure clients/patients prevent and/or avoid untoward bad outcomes (e.g., posting on social media that one has suicidal thoughts instead of calling a crisis line and/or setting up an appointment)?

Which Frameworks Are Used by Disciplines Regarding the Development of TBH Competencies?

Overview

Professional organizations and regulatory boards have to attend to clinical standards (i.e., professional conduct, practice and treatment guidelines, standards of care, scope of practice) promulgated by professional organizations/associations and licensing boards—with legal and regulatory requirements, which vary according to state licensing boards. In view of the considerable skepticism about healthcare delivered over the Internet, it behooves practitioners to be fully aware of the evolving law (R. Waters, personal communication, September 11, 2002 (Maheu et al. 2004). Professional associations and regulatory boards by nature are responsive to sentinel events and therefore may be limited in how comprehensive or relevant they can be when it comes to an area are rapidly evolving as technology (Maheu et al. 2004; Luxton et al. 2016).

With rapidly changing marketplace demands resulting from health care reform with an increasing role of technology (Ternullo and Locke 2016), our educational and service delivery programs are pressed to deliver professionals who are fully prepared to respond proficiently as well as legally and ethically. Hence, we need patient- and learner-centered care and supervision, and this need is particularly evident with the challenges evidenced in TBH (Maheu 2001, Maheu et al. 2004; Hilty et al. 2015f; Callan et al. 2016; Luxton et al. 2016).

In MH, a competency in the form of a measurable human capability required for effective performance may include individual and aggregate components of skill, knowledge, attitudes or personal qualities. The latter category includes attitudes, but may have emotional, personality, value, and/or other components. These elements affect how one conducts oneself, habits kept, ways of interacting, manners (Marrelli et al. 2005) to broader culturally determined behaviors. In medicine, this is articulated as “the habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice” (Epstein and Hundert 2002; Norman 1985).

All MH, medical, dental and nursing fields have proposed competencies that are primarily emphasized and evaluated during training, followed by multiple-choice tests for becoming certified/boarded to establish a minimum clinical care capacity. Most are in line with the competency definitions above and use the word capability (or a synonym like “ability”). Fields strive for validity, reliability, feasibility, and other practical considerations regarding assessment. The hope is that what is measured also has fidelity to actual practice. In psychology and psychiatry, some psychology boards have both oral and written exams and some certification bodies (e.g., American Board of Professional Psychology (ABPP)) bodies use oral exams, as well; otherwise, oral examinations/boards have been generally discontinued due to inadequate validity and subjectivity in assessment. Many things are difficult, still, to assess, like skill in self-assessment and reflection, decision-making, and handling ethical dilemmas. Peer review is a staple in medicine, along with things like morbidity and mortality conferences, but these do not reduce the rate of medical errors (Institute of Medicine 2000, 2001).

Examples of Competency Movements: Psychology and Medicine

Psychology has worked for several decades to identify and assess practice competencies primarily during graduate training (Rubin et al. 2007). Beyond graduate level training, there has been little focus on competency in independent practice. Models that define psychology competencies and levels of competency have been developed (Fouad et al. 2009; Rodolfa et al. 2005, Rodolfa et al. 2013), but remain more conceptual than applied in practice. In psychology, one model conceptualizes competencies for the practice of psychology across four developmental levels: (1) entry level supervised, (2) advanced supervised, (3) entry to practice through 3 years, (4) after 3 years of practice (Rodolfa et al. 2013). Psychologists put forward guidelines for assessing competencies (Kaslow et al. 2007; Leigh et al. 2007) and identified challenges to this process (Lichtenberg et al. 2007).

The American Psychological Association Educational Directorate published a guidebook on competency benchmarks in 2012 (American Psychological Association Educational Directorate). More recently, the Association of State and Provincial Psychology Boards (ASPPB) made notable efforts to define and measure competencies for psychologists who practice independently (ASPPB 2014). The concept of maintenance of competencies and developing a skill-based assessment at the time of licensure renewal is a current project. This substantial work by psychologists will lend itself to telecompetencies at some point. The Association for State and Provincial Psychology Boards (ASPPB) is currently developing a skills based exam to be used by psychology licensing boards.

Competency-based medical education focuses on skill development more than knowledge acquisition (Frank et al. 2010; Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Lifelong Learning 2014). ACGME specifies domains of patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, systems based practice, professionalism, and interpersonal skills and communication (ACGME 2013). The evidence-based CanMEDS competency framework describes the knowledge, skills and abilities that specialist physicians need for better patient outcomes, based on the seven roles that all physicians play: (1) medical expert, (2) communicator, (3) collaborator, (4) manager, (5) health advocate, (6) scholar, and (7) professional (Royal College 2005; Frank 2005).

The TP competencies (Hilty et al. 2015c) (Table 1) followed a review of TP education and training (Sunderji et al. 2015) and medical education competencies (Harden et al. 1999; Callan et al. 2016; Cassel 2004). The authors suggested (1) novice/advanced beginner, competent/proficient, and expert levels; (2) domains of patient care, communications, system-based practice, professionalism, practice-based improvement, knowledge and technology know-how; and (3) pedagogical methods to teach and evaluate skills.

These competencies were adapted from the milestone levels of the Dreyfus model: Level 1—novice (medical student); Level 2—advanced beginner (first-year resident); Level 3—competent (senior resident); 4—proficient (graduating resident); 5—expert (expert in TP) (Dreyfus and Dreyfus 1980).

Teaching and Assessment Methods of Competencies

Each client/patient, learner and teacher walk different professional and personal paths, such that meeting goals requires careful listening, systematic collecting of information and deliberate reflection and planning (Miller 1990). Ideally, one determines the objective/goal, picks the instructional method (e.g., bedside/clinic, case/discussion format), and stages the educational events (Kolb 1984). Assessment must be viewed as a continuum from the earliest stages of professional training through continued learning in practice (Bashook 2005). Self-assessment is expected in many regards, particularly with regard to expertise, its limits and what to do when those limits are reached (Leigh et al. 2007).

Elementary evaluation should include four different levels: (1) reaction, (2) learning, (3) behavior, and (4) results (Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick 2009). Level one evaluation assesses a participant’s reactions to setting, materials, and learning activities, ensuring learning and subsequent application of program content (Rouse 2011), and can be captured through satisfaction ratings. Level two of evaluation involves determining the extent to which learning has occurred, often employing performance testing, simulations, case studies, plays, and knowledge exercises (e.g., pre-and post-test). Level three attempts to determine the extent to which new skills and knowledge have been applied ‘on the job’, such as in the healthcare setting. Level four of evaluation involves measuring system-wide or organizational impact of training.

Disciplines Practicing TBH: Comparing Similarities and Differences of Steps toward Competencies

Overview

TBH competencies are an opportunity for common ground and standardizing its training and assessment could add to traditional licensing, board or clinical guidelines and standards. Since psychiatry, psychology, social work, counseling, marriage/family and other related fields vary in many regards, though, is it realistic to get providers capable at a common level? Some disciplines have unique skill sets (e.g., psychiatric prescribing, pastoral counseling). Common training goals for specific clinical skills are possible (e.g., mental status exams, intake, informed consent, assessment, triage, treatment planning, termination). There is also a foundation of legal, ethical and privacy standards. TBH may require better planning in order to deal with emergencies (e.g., understanding originating site and community emergency resources, including response times for fire and police departments, working with local collaborators). Overall, intra-professional and interprofessional consensus would be a worthy goal for TBH competencies. An outline for interprofessional TBH competencies was introduced in the early 2000s (Maheu et al. 2004).

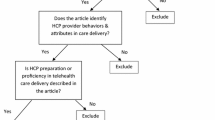

Behavioral disciplines approaches to practice with technology can be compared competency targets (Tables 2 and 3). This comparison uses the TP domains of client/patient care, communications, system-based practice, professionalism, practice-based improvement, knowledge and technology know-how. This comparison focuses on content, process and the vision of the disciplines rather than stratifying competencies across novice/advanced beginner, competent/proficient, and expert levels. The documents from the many disciplines discussed technology issues variably and were rated: tier 1 (mentioned as important in a document; given one checkmark); tier 2 (discussed in-depth (suggestions on how to approach and/or evaluate; given two checkmarks); and tier 3 (evidence based). Few if any documents were rated tier 3.

The scope of existing documents is broad (e.g., practice of telepsychology; standards for technology and social work practice), mid-range (e.g., American Telemedicine Association’s video- or Internet-based services), and/or narrow (e.g., preliminary guidelines for using social media). The field of psychology has spelled out considerations for using technology in practice, and social work and marriage and family therapy have also begun significant work on how the Internet, social media and other asynchronous communication options influence practice.

Since the TP competencies are the most well described model to date, these will be described first and other disciplines’ work thereafter.

Psychiatry and the TP Competencies

The TP competencies (Hilty et al. 2015c) (Table 1) followed the four milestone levels of the Dreyfus model (above), but this was simplified to three levels: novice/advanced beginner (e.g., advanced medical student, early resident, or other trainees); competent/proficient (e.g., advanced resident, graduating resident, faculty, attending, or interdisciplinary team member); and expert (e.g., advanced faculty, attending, or interdisciplinary team member). Patient care was divided into two parts: (1) clinical history, interviewing, assessment, and treatment; and (2) administrative-based issues related to care documentation, EHR, medico-legal, billing, and privacy/confidentiality. Systems-based practice includes outreach, interprofessional education (IPE), providers at the medicine-psychiatric interface, geography, models of care, and safety. Attitude, integrity, ethics, scope of practice and cultural and diversity issues were grouped within professionalism. Communication, knowledge and practice-based learning domains added additional dimensions and an additional domain of technology has been suggested to include some behavioral, communication and operational aspects related to technology.

An example core competency is history taking. A novice practitioner would probably just start the session with the client/patient, but a competent/proficient provider would open the session with an informed consent discussion for telehealth, which involves providing information, alternative options and a tacit summary of pros/cons. S/he would also collect basic information (if not already collected) about the remote environment, access to others for help, and community resources for worst case scenarios (e.g., the client/patient states suicidal thoughts during the interview). S/he would mention that it is not being recorded, which is a common misunderstanding for new clients/patients. There are now few if any cons to be discussed at this point (e.g., disconnections). Good TBH care includes do’s and don’ts. A novice may not replace a handshake with other non-verbal behaviors or may not consider the omission of olfactory data (e.g., perfume, alcohol on the client’s/patient’s breath). A competent/proficient provider would adjust the screen and audio during the interview, particularly if screening for movement disorders, intoxication/withdrawal or other medical problems. S/he would project her/himself approximately 15% more for engagement as practices in the television, business and other industries. S/he would avoid dressing in a distracting way (e.g., bold stripes on ties, blouses/shirts or distracting earrings and bracelets). Initial and longitudinal evaluation/assessment would consider if the technology appears to affect the flow of conversation, client’s/patient’s presentation/personality, and/or development of transference. Cultural and language issues may also be affected by technology (e.g., willingness to use it, presentation of symptoms). Expert competencies may be a composite of TBH-specific, clinical reasoning, system-based practice, and/or administrative complexity.

The teaching and evaluation plan for TP competencies discussed a combination of methods related to curricular, rotation and supervisory contexts (Table 2). The overarching goals are to facilitate skill development over time via feedback (Hilty et al. 2015c) and program improvement (Tekian et al. 2015).

TP competencies described above are likely to be shepherded by the Association of American Directors of Psychiatry Residency Training (AADPRT), which has developed the other competencies, works with primary and specialty medicine areas, and reports to the ACGME. The American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) oversees board accreditation and regular recertification, with collaboration with AADPRT (clinical skill evaluations and verifications in training) and lifelong learning platform created by the American Psychiatric Association.

American Counseling Association (ACA)

The ACA Code of Ethics addresses technology related to clinical practice and education (ACA 2014). Section H addresses “Distance Counseling, Technology, and Social Media.” Section F.2.c. “Online Supervision” discusses that, “When using technology in supervision, counselor supervisors are competent in the use of those technologies. Supervisors take the necessary precautions to protect the confidentiality of all information transmitted through any electronic means” and F.7.b. “Counselor Educator Competence” addresses teaching via technology.

Marriage and Family Therapy (AAMFT)

Technology competencies—if adapted—would be shepherded by the AAMFT, which has used the term “Technology-Assisted Professional Services” and to a lesser degree, the term “Couples and Family Therapy Technology” (CFTT) practice. This organization recognized the great benefits and responsibilities inherent in both in-person and technologically-assisted therapeutic and supervisory services. In the recently published set of ethical standards published by AAMFT, the relevant section is Standard VI Technology-Assisted Professional Services (2015). It suggests that members (1) be aware of and compliant with the laws related to the delivery of technology-related practices, be sure that recommended technologies are appropriate for the recipient, transmission be secure, and be used after appropriate education, training or supervision; (2) obtain written consent for the provision of any technology-related services, including the risks, benefits, limitations, and potential issues around confidentiality and security, (3) be able to discern when services are appropriate and if so determine which kinds are most apt, and (4) participate in technology-related services only upon completion of the appropriate education, training, and/or supervision (competence first, then practice consistent with best online practices).

The Association of Marital and Family Therapy Regulatory Board (AMFTRB) published the “Examination in Marital and Family Therapy” for marriage and family therapists, which addresses the use of various technologies. Indeed, participants in this examination are now assessed over a number of areas including the use of technology in accordance with legal, ethical and professional standards (Task Statement 06.17), the impact of clients’ use of resources including online assessments (Knowledge Statement 59), statutes, case law, and regulations related to online practices (Knowledge Statement 62), implications of the use of technology by clinicians and administrative staff (Knowledge Statement 65), ethical considerations in the use of technology by clinicians and administrative staff (Knowledge statement 66), the impact of technology on client systems (Knowledge Statement 67), and the conducting of online therapy (Knowledge Statement 68) (AMFTRB 2015). These guidelines specified clinical (i.e., skills, impact on relationships, ethics, informed consent, confidentiality), security and data management, and legal and regulatory issues.

Psychology (American and Canadian Psychological Associations)

Telepsychology competencies were raised within the scope of professional competence related to emerging telepractice issues (e.g., lack of adherence to limits set by licensing laws, informed consent requirements, mandated reporting, and other fundamental precepts of legal and ethical care) (Maheu and Gordon 2000). The Ohio Psychological Association (OPA 2013) published telepsychology competencies and Canadian psychologists published a proposed set of telepsychology competencies in 2014 (Johnson 2014). The American Psychological Association Guideline for the Practice of Telepsychology (American Psychological Association 2013) offers eight detailed components in guidelines which pertain to clinical (i.e., ethical, informed consent, documentation, confidentiality, adjusting assessments), educational, legal and regulatory and security and management of data (Table 4).

Social Work (NASW)

The NASW developed “Standards for Technology and Social Work Practice” in 2005 and worked with the Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB), Council on Social Work Education (CSWE), and Clinical Social Work Association (CSWA) to develop the Standards for Technology in Social Work Practice in 2017 (NASW 2017). Events at individual practitioner level were noted to include: e-mail and the Web make Internet-mediated direct practice possible on a global scale; social workers and clients can uncover vast Web-based sources for information that can enhance the likelihood of effective interventions; and support groups for people at risk can be easily created and moderated. At the agency level, these standards discussed case management programs, which can generate reports, track personnel, automate billing, forecast budgets, and greatly assist service planning and delivery. Finally, at the global level, consultation and conference abilities are at hand and emerging geographic information systems can pinpoint community assets and needs.

The specific goals of the standards are to maintain and improve the quality of technology-related services provided by social workers; serve as a guide to social workers incorporating technology into their services; help social workers monitor and evaluate the ways technology is used in their services; and inform clients, government regulatory bodies, insurance carriers, and others about the professional standards for the use of technology in the provision of social work services. Specifically, social workers addressed clinical (i.e., ethics, skillsets, therapeutic relationship changes), modes of technology and support (e.g., Internet, video, telephone), cultural, education/training (i.e., clinicians, public), legal and regulatory professional practice, and privacy issues. They also inferred that clinicians select technology considering the modes’ pros/cons.

Discussion

The state of TBH—a more fitting term than TMH—is improving due increased evidence and competencies are the integrative link between excellence in clinical practice, education and technology—they are much needed in this era of service delivery and health care. Traditional training, evaluation and faculty development can translate TBH research on clinical outcomes and models of care to generations to come. In turn, these clinicians will leverage resources more efficiently and have capacity to reach a wide range of populations (e.g., refugees across the world). Best practices from each discipline (AAMFT, ACA, American Psychiatric Association, American Psychological Association, NAADAC or AAP, NASW)—if shared and integrated for competencies—will potentially strengthen this movement. Technology is moving clinicians toward an e-practice with a broader array of options on an e-BH spectrum—competencies are needed for this practice, as well (Hilty et al. 2015b). From a learner perspective, new generations have advantages (e.g., positive attitude, facility and know-how with technology and disadvantages (e.g., personal rather than professional experience) (Behnke 2008; Bishop et al. 2011; Hilty et al. 2015a, b).

TBH competencies would have significant impact for the disciplines, organizations/associations and individual professionals. Traction most likely requires intra- and interprofessional, interest, communication and administration up and down the chain of hierarchy. Consensus by all the groups makes competencies stronger, as is the case with guidelines. Professional organizations are unfortunately, due to many other demands, unlikely put out individual competencies and they would not be standardized. After this initial work, the development of subdomain competencies among the different professions is logical; or some will use some but not others. Not having appropriate skill is a major risk—in-person or by TBH, of course.

If a competency model is used for employment decisions, it must adhere to rigorous state and federal standards and a substantially tested model would be requested (Marrelli et al. 2005). It seems fitting that competencies be integrated better into existing standards for professional conduct, practice and treatment guidelines, clinical care, and scope of practice, which are promulgated by professional organizations/associations and by professional licensing boards. Disciplines and organizations involved with TBH need to consider certification/accreditation and ensure quality care. TBH is also a call to action as it behooves practitioners—whether practicing in-person or via TBH—to be fully aware of standards from their guild and the evolving law. Standards and guidelines of professional conduct are changing simply as a result of developing telehealth technology, but interpretations of conduct are needed and ongoing evaluation by professions is indicated.

The modest TP competencies were designed with a medical model of clinical care in mind, but the tiering of levels makes them broadly applicable to trainees, clinicians, and organizations in other MH disciplines. The foundation of pedagogy and evaluation can be improved and other disciplines’ policies suggest that additional areas of practice and technology need to be added. Consensus-based approaches (i.e., Delphi) are being used by the Coalition for Technology in Behavioral Science (CTiBS) at this time to poll disciplines for input and improve draft TBH competencies. Much more input is needed from various stakeholders, including patients/clients, family/caregivers, professionals in healthcare, behavioral science, social science and technology; and leadership by professional organizations that function across disciplines (e.g., the ATA). Research and evaluation is needed regardless of the competency set, in order to evaluate the teaching/training and skill development by learners. Data collection could include literature review, observations, surveys, focus groups, structured interviews, behavioral event interviews, and other logs (Marrelli et al. 2005).

There are many limitations to this initial attempt to tackle the three questions about TBH competencies within/across disciplines/fields. First, core competencies across disciplines may make sense, but accessory/adjunct competencies are likely needed for many disciplines in order to capture the depth and breadth of their practice. Second, competencies must be evaluated, modified and improved—including the published TP ones. Third, aside from the developers, learners and many others involved, it is not realistic to expect TBH competencies to “work” without faculty development and corollary professional development; without involvement of major stakeholders (e.g., licensing boards, individual and organization certification and accreditation organizations, professional organizations). Fourth, it has not been discussed exactly how TBH competencies for clinical care and education direct align with serving patients’ needs and expectations and how reimbursement streams align as well. In a time when patient-centered healthcare is expected, patient perspective in the development of guidelines is now a standard (Tseng and Hicks 2016). Fifth, some institutions (e.g., Indian Health Service, Veteran’s Administration) are unique and better integration with international standards and guidelines may be needed, considering the global reach of technology and its multicultural diversity. Sixth, it is unclear if “expert” levels are needed across professions, though this level is common in medical education and some other frameworks for training. Seventh, better definition within and between each of the professions or disciplines is needed (e.g., Table 3 makes broad generalizations).

Conclusions

TBH in the form of synchronous video conferencing is effective, well received and a standard way to practice. Current guidelines, policies and other documents discuss clinical skills related to technology, but only TP competencies provide a practical “how to” approach for training and evaluation. TBH competencies across psychiatry/medicine, psychology, social work, counseling, marriage/family, addictions, behavioral analysis and other behavioral sciences are needed to ensure quality of care, clinical skill, steer training, promote lifelong learning and spur organizational change related to technology. Levels of competencies such as novice/advanced beginner, competent/proficient, and expert could be linked to domains of patient care, communication, system-based practice, professionalism, practice-based improvement, knowledge and technology know-how—or other/better domains. TBH skill-based competencies may be part of a broader e-mental health spectrum of skills as technology moves patients, providers and systems into a new era of healthcare. Dilemmas may include finding common ground across disciplines, setting minimal requirements, training/continuing education/certification/accreditation, availability of resources and change management. Finally, research is needed and better integration of potential competencies with international standards and guidelines is suggested, considering the global reach of technology and its multicultural diversity.

References

Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (2013). Common Program Requirements. Retrieved from https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs2013.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy (2015). Standard VI technology-assisted professional services. Retrieved from https://www.aamft.org/iMIS15/AAMFT/Content/legal_ethics/code_of_ethics.aspx. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

American Association of Medical Colleges (2014). Core entrustable professional activities for entering residency. Retrieved from https://www.aamc.org/download/427456/data/spring2015updatepptpdf.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

American Counseling Association (2014). Code of ethics. Retrieved from https://www.counseling.org/resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

American Medical Association (2011). Opinion 9.124 - Professionalism in the Use of Social Media. AMA Code of Medical Ethics. Retrieved from http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion9124.page. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

American Psychological Association Guideline for the Practice of Telepsychology (2013). Retrieved from http://www.apapracticecentral.org/ce/guidelines/telepsychology-guidelines.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

American Telemedicine Association (2009). Practice guidelines for videoconferencing-based telemental health. Retrieved from http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-source/standards/practice-guidelines-for-videoconferencing-based-telemental-health.pdf?sfvrsn=6. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

American Telemedicine Association (2013). Practice guidelines for video-based online mental health services. Retrieved from http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-source/standards/practice-guidelines-for-video-based-online-mental-health-services.pdf?sfvrsn=6. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

American Telemedicine Association (2017). Practice guidelines for telemental health with children and adolescents. Retrieved from: https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/AMERICANTELEMED/618da447-dee1-4ee1-b941-c5bf3db5669a/UploadedImages/Practice%20Guideline%20Covers/NEW_ATA%20Children%20&%20Adolescents%20Guidelines.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

Andersson, G., Carlbring, P., Holmstrom, A., Sparthan, E., Furmark, T., Nilsson-Ihrfelt, E., & Ekselius, L. (2006). Internet-based self-help with therapist feedback and in vivo group exposure for social phobia: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(4), 677–686.

Association of Marital and Family Therapy Regulatory Boards. (2015). 2015 AMFTRB national marital and family therapy examination: handbook for candidates. Retrieved from http://www.amftrb.org/exam.cfm. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

Association of State and Provincial Psychology Boards (2014). Maintenance of Competence for Licensure (MOCL) White Paper. Retrieved from http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.asppb.net/resource/resmgr/Guidelines/Maintenance_of_Competence_fo.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

Australian Psychological Society (2011). Guidelines for Providing Psychological Services and Products Using the Internet and Telecommunications Technology Retrieved from: https://aaswsocialmedia.wikispaces.com/file/view/EG-Internet.pdf.

Backhaus, A., Agha, Z., Maglione, M. L., Repp, A., Ross, B., Zuest, D., Rice-Thorp, N. M., Lohr, J., & Thorp, S. R. (2012). Videoconferencing psychotherapy: a systematic review. Psychological Services, 9(2), 111–131.

Bashook, P. G. (2005). Best practices for assessing competence and performance of the behavioral health workforce. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 32, 563–592.

Behnke, S. (2008). Ethics in the age of the internet. Monitor on Psychology, 39(7), 74.

Bishop, M., Yellowlees, P., Gates, C., & Silberman, G. (2011). Facebook goes to the doctor. ACM Press, 978-1-4503-1082-6/11/12, pp.13–20. Retrieved from http://nob.cs.ucdavis.edu/bishop/papers/2011-gtip/socmed.ps. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

Brenner, P. (1984). From novice to expert. Boston: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co..

British Psychological Society (2009). The Provision of Psychological Services via the Internet and Other Non-direct Means. Retrieved from The provision of psychological services via the Internet. Accessed 15 Aug 2017 http://www.bps.org.uk/system/files/Public%20files/psychological_services_over_the_internet.pdf

Brown, M. (1994). An introduction to the discourse on competency-based training (CBT) in Deakin University Course Development Centre (Ed.), A collection of readings related to competency-based training (pp. 1–17). Victoria, Australia: Victorian Education Foundation, Deakin University. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED384695.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

Callan, J., Maheu, M., & Bucky, S. (2016). Crisis in the behavioral health classroom: enhancing knowledge, skills, and attitudes in telehealth training. In M. Maheu, K. Drude, & S. Wright (Eds.), Field guide to evidence-based, technology careers in behavioral health: Professional opportunities for the 21st century. New York: Springer.

Cassel, C. K. (2004). Quality of care and quality of training: a shared vision for internal medicine? Annals of Internal Medicine, 140(11), 927–928.

Celio, A. A., Winzelberg, A. J., Wilfley, D. E., Eppstein-Herald, D., Springer, E. A., Dev, P., & Taylor, C. B. (2000). Reducing risk factors for eating disorders: Comparison of an Internet- and a classroom-delivered psychoeducational program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychol, 68(4), 650–657.

Christensen, H., Griffiths, K., & Evans, K. (2002). E-mental health in Australia: implications of the internet and related technologies for policy. Canberra, Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing. Retrieved from http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/apcity/unpan046316.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

Christensen, H., Griffiths, K., Groves, C., & Korten, A. (2006). Free range users and one hit wonders: community users of an Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy program. Australian New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40(1), 9–62.

Clarke, G., Eubanks, D., Reid, E., Kelleher, C., O'Connor, E., DeBar, L. L., Lynch, F., & Gullion, C. (2005). Overcoming depression on the Internet (ODIN) (2): a randomized trial of a self-help depression skills program with reminders. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 7(2), e16.

Dreyfus, S. E., & Dreyfus, S. L. (1980). A five-stage model of the mental activities involved in directed skill acquisition. Retrieved from http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a084551.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

Epstein, R. M., & Hundert, M. (2002). Defining and assessing professional competence. Journal of the American Medical Association, 287, 226–235.

Ferreira-Lay, P., & Miller, S. (2008). The quality of internet information on depression for lay people. Psychiatric Bulletin, 32 , 170–173.

Ford, K. (2014). Competency-based education, history, opportunities, and challenges. UMUC Center for Innovation in Learning and Student Success (CILSS). Retrieved from https://www.umuc.edu/innovatelearning/upload/cbe-lit-review-ford.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

Frank, J. R. (2005). The CanMEDS 2005 Physician Competency Framework. Retrieved from http://rcpsc.medical.org/canmeds/CanMEDS2005/ CanMEDS2005_e.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

Frank, J. R., Mungroo, R., Ahmad, Y., Wang, M., De Rossi, S., & Horsley, T. (2010). Toward a definition of competency-based education in medicine: a systematic review of published definitions. Medical Teacher, 32(8), 631–637. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.500898.

Fouad, N. A., Grus, C. L., Hatcher, R. L., Kaslow, N. J., Hutchings, P. S., Madson, M. B., & Crossman, R. E. (2009). Competency benchmarks: A model for understanding and measuring competence in professional psychology across training levels. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 3(4, Suppl), S5-S26.

Frydman, G. J. (2010). A patient-centric definition of participatory medicine. Retrieved from http://e-patients.net/archives/2010/04/a-patient-centric-definition-of-participatory-medicine.html. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

Glueck, D. (2013). Establishing therapeutic rapport in telemental health. In K. Myers & C. L. Turvey (Eds.), Telemental health (pp. 29–46). New York: Elsevier pp.

Harden, R. M., Crosby, J. R., & Davis, M. H. (1999). AMEE guide no. 14: outcome-based education: part 1—an introduction to outcome-based education. Medical Teacher, 21, 7–14.

Hilty, D. M., Marks, S. L., & Nesbitt, T. S. (2002). How telepsychiatry affects the doctor-patient relationship: communication, satisfaction, and additional clinically relevant issues. Primary Psychiatry, 9(9), 29–34.

Hilty, D. M., Liu, W., Marks, S. L., & Callahan, E. C. (2003). Effectiveness of telepsychiatry: a brief review. Canadian Psychiatric Association Bulletin,, 35 10–17.

Hilty, D. M., Ferrer, D. C., Parish, M. B., Johnston, B., Callahan, E. J., & Yellowlees, P. M. (2013a). The effectiveness of telemental health: a 2013 review. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health, 19(6), 444–454. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2013.0075.

Hilty, D. M., Srinivasan, M., Xiong, G. L., Ferranti, J., & Li, S. T. (2013b). Lessons from psychiatry and psychiatric education for medical learners and teachers. International Review of Psychiatry, 25, 329–337.

Hilty, D. M., Belitsky, R., Cohen, M. B., Cabaniss, D. L., Dickstein, L. J., Bernstein, C. A., & Silberman, E. K. (2015a). Impact of the information age residency training: the impact of the generation gap. Academic Psychiatry, 39(1), 104–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-014-0196-6.

Hilty, D. M., Chan, S., Torous, J., Mahautmr, J., & Mucic, D. M. (2015b). New frontiers in healthcare and technology: Internet- and web-based mental options emerge to complement in-person and telepsychiatric care options. Journal of Health and Medical Informatics, 6(4), 1–14.

Hilty, D. M., Green, J., Nasatir-Hilty, S. E., Johnston, B., & Bourgeois, J. A. (2015c). Mental healthcare to rural and other underserved primary care settings: benefits of telepsychiatry, integrated care, stepped care and interdisciplinary team models. Journal of Nursing Care, 4, 2. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-1168.1000237.

Hilty D. M., Rabinowitz, T., Shoemaker, E. Z., Snowdy, C., & Turvey, C. (2015d). Telepsychiatry’s evidence base shows effectiveness: new models (asynchronous), more psychotherapy, and innovations with special populations (Child, Gero, Other), Symposium, American Psychiatric Association, Toronto, Canada.

Hilty, D. M., Yellowlees, P. M., Parish, M. B., & Chan, S. (2015e). Telepsychiatry: effective, evidence-based and at a tipping point in healthcare delivery. Psychiatric Clinics of North American, 38(3), 559–592.

Hilty, D. M., Crawford, A., Teshima, J., Chan, S., Sunderji, N., Yellowlees, P. M., Kramer, G., O’Neill, P., Fore, C., Luo, J. S., & Li, S. T. (2015f). A framework for telepsychiatric training and e-health: competency-based education, evaluation and implications. International Review of Psychiatry, 27(6), 569–592.

Hilty D.M., Rabinowitz T.R., McCarron R.M., Katzelnick D.J., Chang T., Fortney J., & Katon, W. J. (2017 Submitted). Telepsychiatry and e-mental health models leverage stepped, collaborative, and integrated services to primary care. Psychosomatics.

Horvath, A. O., del Re, A. C., Fluckiger, C., & Symonds, D. (2011). Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 48, 9–16.

Institute of Medicine. (2000). To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academic Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21 st century. Washington, DC: National Academic Press.

Jenkins-Guarnieri, M. A., Pruitt, L. D., Luxton, D. D., & Johnson, K. (2015). Patient perceptions of telemental health: systematic review of direct comparisons to in-person psychotherapeutic treatments. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health, 21(8), 652–660.

Johnson, G. (2014). Toward uniform competency standards in telepsychology: a proposed framework for Canadian psychologists. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 55(4), 291–302.

Kalk, N. J., & Pothier, D. D. (2008). Patient information on schizophrenia on the Internet. Psychiatric Bulletin, 32, 409–411.

Kaslow, N. J. (2007). The competency movement within psychology: an historical perspective. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38, 452–462.

Kirkpatrick, J., & Kirkpatrick, W. (2009). The Kirkpatrick four levels: a fresh look after 50 years, 1959–2009. Retrieved from http://www.kirkpatrickpartners.com/Portals/0/Resources/Kirkpatrick%20Four%20Levels%20white%20paper.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Laranjo, L., Arguel, A., Neves, A. L., Gallagher, A. M., & Kaplan, R. (2015). The influence of social networking sites on health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Associations, 22(1), 243–256.

Leigh, I. W., Bebeau, M. J., Neslon, P. D., Rubin, N. J., Smith, I. L., Lichtenberg, J. W., Portnoy, S., & Kaslow, N. J. (2007). Competency assessment models. Professional Psychology, 38(5), 463–473.

Lichtenberg, J., Portnoy, S., Bebeau, M., Leigh, I. W., Nelson, P. D., Rubin, N. J., Smith, I. L., & Kaslow, N. J. (2007). Challenges to the assessment of competence and competencies. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38, 474–478.

Ljotsson, B., Lundin, C., Mitsell, K., Carlbring, P., Ramklint, M., & Ghaderi, A. (2007). Remote treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder: a randomized trial of internet-assisted cognitive behavioural therapy. Behavioral Research Therapy, 45(4), 649–661.

Luxton, D., Nelson, E., & Maheu, M. (2016). Telemental health best practices. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Maheu, M. (2001). Exposing the risk yet moving forward: a behavioral e-health model. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 6(4). http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2001.tb00130.x/full.

Maheu, M., Whitten, P., & Allen, A. (2001). eHealth, Telehealth & Telemedicine: a guide to startup and success. New York: Jossey-Bass.

Maheu, M., Pulier, M., Wilhelm, F., McMenamin, J., & Brown-Connolly, N. (2004). The mental health professional and the new technologies: a handbook for practice today. Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Maheu, M., Drude, K., Hertlein, K., Lipschutz, R., Wall, K. Long, ..., & D.M. Hilty: (2017) An interdisciplinary framework for telebehavioral health competencies. J Technology in Behav Sci, In Press

Miller, G. (1990). The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Academic Medicine`, 65(Suppl), S63–S67.

Marrelli, A. F., Tondora, J., & Hoge, M. A. (2005). Strategies for developing competency models. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 32(5–6), 533–560.

Moskowitz, D. S., & Young, S. N. (2006). Ecological momentary assessment: what it is and why it is a method of the future in clinical psychopharmacology. Journal of Psychiatry and Neurosciences JPN, 31(1), 13–20.

Mucic, D., & Hilty, D. M. (2015). Key issues in e-mental health. New York: Springer Publishing.

Mucic, D., Hilty, D. M., Parrish, M. B., & Yellowlees, P. M. (2015). Web- and Internet-based services: education, support, self-care and formal treatment approaches. In D. Mucic & D. M. Hilty (Eds.), Key issues in e-mental health (pp. 173–192). New York: Springer Publishing.

Myers, K., van der Stoep, A., Zhou, C., McCarty, C. A., & Katon, W. (2015). Effectiveness of a telehealth service delivery model for treating attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: results of a community-based randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(4), 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2015.01.009.

National Association of Social Workers, Association of Social Work Boards, Council on Social Work Education, and Clinical Social Work Association (2017). Standards for Technology in Social Work Practice. Retrieved from https://www.naswpress.org/publications/standards/technology.html. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

National Association of Social Workers Standards for Technology and Social Work Practice (2005). Retrieved from http://www.socialworkers.org/practice/standards/naswtechnologystandards.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

Nelson, E., Duncan, A., Peacock, G., & Bui, T. (2012). School-based telemedicine and adherence to national guidelines for ADHD evaluation. Psychological Services, 9(3), 293–297.

Nelson, E. L., Duncan, A. B., & Lillis, T. (2013). Special considerations for conducting psychotherapy via videoconferencing. In K. Myers & C. L. Turvey (Eds.), Telemental health: clinical, technical and administrative foundations for evidenced-based practice (pp. 295–314). San Francisco: Elsevier.

Nemoto, K., Tachikawa, H., Sodeyama, N., Endo, G., Hashimoto, K., Mizukami, K., & Asada, T. (2007). Quality of Internet information referring to mental health and mental disorders in Japan. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 61(3), 243–248.

Norman, G. R. (1985). Defining competence: a methodological review. In V. R. Neufeld & G. R. Norman (Eds.), Assessing clinical competence (pp. 15–35). New York: Springer.

Ohio Psychological Association (2013). Areas of competence for psychologists in telepsychology. Retrieved from http://www.ohpsych.org/about/files/2012/03/FINAL_COMPETENCY_DRAFT.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

Ostrowski, J., & Collins T., (2016). A comparison of telemental health terminology used across mental health state licensure boards. Professional Counselor. Retrieved from: http://tpcjournal.nbcc.org/a-comparison-of-telemental-health- terminology-used-across-mental-health-state-licensure-boards/. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

Rabinowitz, T., Murphy, K. M., Amour, J. L., Ricci, M. A., Caputo, M. P., & Newhouse, P. A. (2010). Benefits of a telepsychiatry consultation service for rural nursing home residents. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health, 16(1), 34–40.

Richardson, L. K., Frueh, B. C., Grubaugh, A. L., Egede, L., & Elhai, J. D. (2009). Current directions in videoconferencing telemental health research. Clinical Psychology, 16(3), 323–328.

Ritterband, L. M., & Thorndike, F. (2006). Internet interventions or patient education web sites? Journal of Medical Internet Research, 8(3), e18. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.8.3.e18).

Rodolfa, E., Bent, R., Eisman, E., Nelson, P., Rehm, L., & P. Ritchie. (2005). Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 3, 347–354.

Rodolfa, E. R., Greenberg, S., Hunsley, J., Smith-Zoeller, M., Cox, D., Sammons, M., Caro, C., & Spivank, H. (2013). A competency model for the practice of psychology. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 7(2), 71–83.

Rouse, D. N. (2011). Employing Kirkpatrick's evaluation framework to determine the effectiveness of health information management courses and programs. Perspectives in Health Informatics Management, 8(Spring), 1c (Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3070232/. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, CanMEDS Framework (2005). Retrieved from http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/canmeds/framework. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

Rubin, N. J., Bebeau, M. J., Leigh, I. W., Lichtenberg, J. W., Nelson, P. D., Portnoy, S. M., Smith, L., & Kaslow, N. J. (2007). The competency movement within psychology: an historical perspective. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38(5), 452–462.

Sunderji, N., Crawford, C., & Jovanovic, M. (2015). Telepsychiatry in graduate medical education: a narrative review. Academic Psychiatry, 39, 55–62.

Tekian, A., Hodges, B.D., Roberts, T.E., Schuwirth., L., Norcini, J. (2015). Assessing competencies using milestones along the way. Medical Teacher, 37(4), 399-402.

Ternullo, J. L., & Locke, S. E. (2016). Tackling changes in mental health practice: the impact of information-age healthcare. In M. Maheu, K. Drude, & S. Wright (Eds.), Field guide to evidence-based, technology careers in behavioral health: professional opportunities for the 21st century. New York: Springer.

Torous, J., Staples, P., Shanahan, M., Lin, C., Peck, P., Keshavan, M., Onnela J. P. (2015). Utilizing a custom application on personal smartphones to assess PHQ-9 depressive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder Journal of Medical Internet Research Mental Health 2(1), e8. At: http://mental.jmir.org/2015/1/e8/. Accessed 15 Aug 2017.

Tseng, E. K., & Hicks, L. K. (2016). Value based care and patient-centered care: divergent or complementary? Current Hematological Malignancy Report, 11(4), 303–307.

Tuxworth, E. (1994). Competence-based education and training: background and origins. In Deakin University Course Development Centre (Ed.), A collection of readings related to competency-based training (pp. 109–123). Victoria: Victorian Education Foundation, Deakin University. Original work published in 1989. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED384695.pdf.

U.S. National Association of Social Workers (2005). Standards for technology and social work practice. http://www.socialworkers.org/practice/standards/naswtechnologystandards.pdf.

World Health Organization. (2011). Telemedicine opportunities and developments in member states. Results of the second global survey on eHealth. Geneva: WHO Press.

Yellowlees, P. M., Odor, A., Iosif, A., Parish, M. B., Nafiz, N., Patrice, K., … & Hilty, D.M. (2013). Transcultural psychiatry made simple: asynchronous telepsychiatry as an approach to providing culturally relevant care. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health, 19(4), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2012.0077.

Acknowledgements

The study was based on information and input from The Coalition for Technology in Behavioral Science, The American Association of Clinical Social Workers Office on Policy, American Association of Marriage and Family Therapists, American Counseling Association, American Psychiatric Association and the Board of Trustees Committee on Telepsychiatry, American Psychological Association and The American Psychological Association Legal Office, The Association of State and Provincial Psychology Boards, National Association for Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors (now called, the Association for Addiction Professionals or AAP, National Association of Social Workers, and American Telemedicine Association and the Telemental Health Interest Group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no financial conflicts of interest. Co-author Marlene Maheu runs the for-profit Telebehavioral Health Institute (https://telehealth.org/about-draft/), which expressly sells Certification Programs (see https://telehealth.org/faq/, http://telehealth.org/telemental-health-certification) that this paper is expressly advocating for in its Abstract. Tracy Luoma is Executive Director at Optum Behavioral Health Salt Lake County. And Richard Long runs a potentially commercial supervision site that could potentially benefit from certification processes (see http://mentalhealth-connect.com/process for pricing). The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hilty, D.M., Maheu, M.M., Drude, K.P. et al. Telebehavioral Health, Telemental Health, e-Therapy and e-Health Competencies: the Need for an Interprofessional Framework. J. technol. behav. sci. 2, 171–189 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-017-0036-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-017-0036-0