Abstract

Qualitative research into adolescents’ experiences of social media use and well-being has the potential to offer rich, nuanced insights, but has yet to be systematically reviewed. The current systematic review identified 19 qualitative studies in which adolescents shared their views and experiences of social media and well-being. A critical appraisal showed that overall study quality was considered relatively high and represented geographically diverse voices across a broad adolescent age range. A thematic meta-synthesis revealed four themes relating to well-being: connections, identity, learning, and emotions. These findings demonstrated the numerous sources of pressures and concerns that adolescents experience, providing important contextual information. The themes appeared related to key developmental processes, namely attachment, identity, attention, and emotional regulation, that provided theoretical links between social media use and well-being. Taken together, the findings suggest that well-being and social media are related by a multifaceted interplay of factors. Suggestions are made that may enhance future research and inform developmentally appropriate social media guidance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It has been claimed that that the widespread adoption of social media by adolescents between 2009 and 2012 has contributed to a decrease in adolescent well-being in the English-speaking world since 2012 (Keyes et al., 2019; Twenge, 2020). This hypothesis appears well-founded. Adolescents can be considered the most devoted social media users, with 63% of 13 to 18-year-olds using social media every day in the US, and 96% of 16 to 24-year-olds in the UK (Rideout & Robb, 2019; ONS, 2017). Furthermore, a growing body of research has demonstrated associations between increased social media use and a range of adverse well-being outcomes, including depressive symptoms and suicidal behavior, often found to be more pronounced amongst young adolescent girls (Twenge et al., 2018; Kelly et al., 2018). Critics have argued, however, that much of the available data is primarily focused on population-level estimates and correlations. Findings have been described as decontextualized, inconsistent, and limited in causational direction, owing to cross-sectional designs (Heffer et al., 2019; Orben & Przybylski, 2019; Coyne et al., 2020). Furthermore, it is often noted that proposed relationships are made without theoretical underpinning, making it difficult for adolescents and their caregivers to ascertain clear guidance about using social media (Erfani & Abedin, 2018; Odgers et al., 2020). Quantitative measures and studies may not be able to capture the full nuance and complexity of adolescent experiences. Researchers have sought to supplement these with qualitative research into adolescents’ experiences of social media and its relationship to well-being. While there have been multiple reviews of quantitative studies, to date no systematic synthesis of this qualitative literature has been conducted, even though the need for this has been identified (Dickson et al., 2018; Odgers, Schueller, & Ito, 2020). Therefore, the current systematic review and thematic meta-synthesis aimed to synthesize the qualitative studies that capture the views and experiences of adolescents of social media use, with a focus on well-being.

The Current Study

This review sought to critically appraise the qualitative literature that can answer the question: what are the views and experiences of adolescents of social media and its relevance to their well-being? The analytic approach taken was metasynthesis, a type of synthesis used to transform initial findings from multiple qualitative research investigations into more abstract, decontextualized results. Meta-synthesis was selected as it has the dual purpose of summarizing qualitative publications and generating new interpretations (Finfgeld-Connett, 2010).

Methods

Review Design

The form of meta-synthesis adopted utilized a model of meta-ethnography, a form of synthesis suited to beliefs and experiences and understandings of complex social phenomena (Atkins et al., 2008). The analysis adhered to the procedures of thematic synthesis (Thomas & Harden, 2008). Thematic synthesis draws on the process of thematic analysis, a method that can be used to synthesize a range of qualitative methods (Braun, & Clarke, 2006). The review followed the recommended six stages of thematic synthesis: (1) defining the research question, the subjects, and the types of studies to be included; (2) identifying and selecting the studies; (3) assessing the quality of the selected studies; (4) analyzing the studies, identifying themes, and translating themes between the studies; (5) generating the themes of the analysis and structuring the synthesis; (6) writing the review (Lachal et al., 2017). The protocol for this review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (Prospero, CRD42019156922) and complied with the ENTREQ guidelines (Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research; Tong et al., 2012).

Inclusion Criteria

This review identified qualitative research studies that investigated the views and experiences of adolescents of social media, with a focus on well-being. In line with previous reviews (Best, Manktelow, & Taylor, 2014), both hedonic and eudaimonic well-being were included. Hedonic well-being describes subjective happiness and typically captures people’s appraisals of their lives, including self-esteem and evaluations of mood. Eudaimonic well-being emphasizes the roles of personal meaning and self-realization (Fig. 1). Table 1 lists the review inclusion criteria.

Literature Search

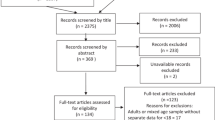

Searches of electronic databases PsycINFO, Medline, Web of Science, and Assia were conducted on 7th February 2020. The search was pre-planned, and terms were informed by preliminary internet searches and previous reviews of adolescent well-being and social media use (Best et al., 2014). Key search terms were combined with Boolean operators ‘OR’ and ‘AND’, and exploded subject headings were used to retrieve all documents containing any of the subject terms. The range of dates was limited from 1st January 2006 to the current day, as 2006 is when Facebook became open to public use. The search terms are listed in Table 2. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. Reference sections of retrieved studies and previous review articles were also searched. Figure 2 illustrates the review process and the number of papers found at each stage. Where studies included both qualitative and quantitative aspects, only the qualitative elements were reviewed. In studies where more than one group of participants was involved (e.g., adolescents and clinicians), only data originating from adolescents were extracted.

Quality Appraisal

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018) framework for qualitative studies was used to evaluate the research. The appraisal tool is the most frequently used tool for quality appraisal in health-related qualitative evidence syntheses and is endorsed by Cochrane and the World Health Organization for such purpose (Long, French, & Brooks, 2020). It was therefore deemed appropriate for use in this review. In practice, the tool provided a generic set of criteria for appraising the strengths and limitations of any qualitative research. The lead author reviewed each included study with the tool’s 10 questions that consider the inclusion of various methodological aspects, including the extent of discussion regarding the choice of design, the suitability of sampling strategy employed, if the analysis was sufficiently rigorous, and the perceived value of the study’s contribution (Table 5). The authors met to discuss any uncertainties or questions arising from the quality appraisal until an agreement had been reached.

Approach to Analysis

The thematic analysis took the form of three stages: a free line-by-line coding of the findings of the included studies; the organization of these ‘free codes’ into related areas to construct ‘descriptive’ themes; and the development of ‘analytical’ themes (Thomas & Harden, 2008). During the first and second stages, data from the original studies were entered into a database using NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2015). The first author then coded the studies inductively according to meaning and content. Line-by-line coding also enabled the translation of concepts between studies to create a bank of codes. The codes were reviewed by the three authors, and following discussion and agreement, grouped into a hierarchical structure based on their similarities and differences. The third stage of synthesis involved going beyond the initial codes to create analytical themes. All authors reviewed the process of theme construction, with disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Results

Overview of Included Studies

The 19 studies that were analyzed were all published within the previous decade. Studies typically included groups of adolescents that ranged in age from 11 to 18 years old. One study had an upper age limit (20) that was just outside the 10–19 age range inclusion criterion (Radovic et al., 2017). This study was nevertheless included because the sample was largely within the required range, with 20-year old’s numbering in low single digits. Samples from general populations were typically recruited from schools. Three studies sampled adolescents who were accessing services for common mental health problems (e.g., anxiety or depression). These studies were included, as these papers were of high quality and provided several insights which the authors deemed applicable to general populations. The 19 studies varied in their aims; some papers were broad in their approach (e.g., exploring how social media impacts mental health), while others focused on specific aspects of social media (e.g., exploring thoughts and feelings about self-images on social media). All papers included the direct views and experiences of adolescents regarding aspects of their well-being and a variety of social media platforms. A range of approaches to data analysis were employed, with thematic analysis being by far the most common. Table 3 describes the characteristics of each study.

Quality Assessment

An evaluation of the studies with the appraisal tool found that most studies demonstrated evidence of meeting the recommendations for qualitative research stipulated in the appraisal criteria. The most common weakness was insufficient evidence of author reflexivity. Table 4 shows the studies assessed by each criterion. A summary of the quality appraisal is shown in Table 5 and the quality of the literature concerning each of the nine domains was as follows.

Aims and Method

Overall, the selected studies set out their research aims clearly, all with justifiable use of a qualitative methodology. Only two papers lacked some clarity regarding the justification of qualitative methodology.

Research Design and Data Analysis

Several studies failed or only partially justified the specific research design used, although this may be explained by space constraints in publishing. Data were collected most often by focus group or interview, sometimes using visual aids to remind participants of specific social media sites. Thematic analysis was the most common form of analysis. Though this type of analysis generally produced informative themes, the studies that used alternative methods tended to provide more in-depth analysis and insights into processes and mechanisms (e.g., grounded theory: Singleton, Abeles, & Smith, 2016).

Sampling and Data Collection

Most papers either met or partially described how and why a certain participant was selected. More generally, however, little attention was given to the limitations of adolescent self-reflection and self-report. Data were collected from participants aged between 11 and 18 years old. All but two of the papers grouped adolescents in relatively large age groups (e.g. from 11 to 18 years of age). Two papers (Burnette, Kwitowski, & Mazzeo, 2017; Jong & Drummond, 2016) included a narrower age range, females aged 12–14 years of age. It was noted that studies that explicitly asked adolescents about well-being and social media use often reported frustrations in data collection. For example, one paper described how “many of the adolescents were unable to define mental health clearly, often confusing it with mental ill-health. Others simply stated that they did not understand the term… some participants said that they did not believe that mental health could be positive” (O’Reilly et al., 2018, p. 4). An apparent consequence of this direct style of questioning was that adolescents often relied on less specific, third-party attributions, rather than reflecting on personal experiences. The same issue appeared less problematic when researchers engaged with participants over specific discrete issues, such as image sharing practices and social media use before bedtime (Bell, 2019; Scott, Biello, & Woods, 2019).

Reflexivity and Ethical Issues

Author reflexivity was also a common absence, an issue that is potentially problematic in an often highly contested and polarized subject area (e.g., Haidt & Allen, 2020). There were, for example, clear examples of author bias reflecting strong concerns about social media in Bharucha et al., (2018), so it was unclear how researcher bias may have impacted data collection, interpretation, and overall integrity of findings. Accordingly, studies of poorer quality contributed less to the review, in line with guidance for conducting meta-ethnographies (Bondas & Hall, 2007).

Findings

The majority of studies provided a clear statement of findings and addressed factors related to credibility and limitations. The common issues present in studies that only partially or did not provide clear findings included the absence of a critical appraisal, often in light of research limitations.

Value of Research

According to the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018) framework, reviewers should appraise the value of research in terms of whether the researcher discusses the contribution the study makes to existing knowledge, if they identify research avenues, or considered how the findings may be transferred to other populations. Twelve of the papers met at least one of these criteria, most often in highlighting the novel and valuable findings their study had produced or in suggesting ideas for the future though only two papers discussed the issues relating to the transferability of their finding (O’Reilly, 2020; Radovic et al., 2017). Notably, Calancie et al. (2017) incorporated clinical strategies into their thematic analysis.

General Critique

As a body of the literature, overall study quality was considered to be relatively high. Studies were drawn from several countries including the UK and USA, Australia, Canada, Singapore, India, Bermuda, and Belgium. Given the global reach of social media, it was welcome to see related studies from non-western countries.

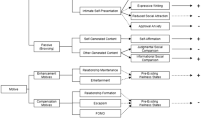

Thematic Analysis

Four central themes relating to adolescent well-being were inductively developed from the analysis: (1) connections, (2) identity, (3) learning, and (4) emotions. Each theme related to a different component of well-being and contained several subthemes detailing how adolescents’ social media use either supported or compromised their well-being. A thematic map is presented in Fig. 3. A table displaying support for each theme across individual papers is presented in Table 6.

First Meta-theme: Connections

The theme connections described how social media either supported or hindered the relationships that adolescents created with their peers, friends, and their family. This theme was referenced in all but one paper.

Growing relationships: Creating and Nurturing Relationships and Social Support

In terms of supporting well-being, nine papers described how adolescents used social media to interact with others who share similar interests and build new friendship groups. Some young people discussed the benefits that social media held over ‘offline’ opportunities to make friends in terms of negotiating shyness (Singleton et al., 2016). Creating relationships was perceived to have other benefits, including helping to build intimacy, popularity, and increased social standing (MacIsaac, Kelly, & Gray, 2018). Social media was also described as a useful tool to maintain and nurture social groups created outside of social media, including keeping in touch with family members and friends who lived long distances away (Radovic et al., 2017). The social media space offered advantages beyond traditional modes of communication, allowing groups to convene on mass to talk and to enjoy media together, share jokes and reflect on experiences as a group (Bell, 2019; Davis, 2012).

Adolescents in seven of the papers also talked about the role of connections on social media as a valued source of support. Connections were represented as receiving positive affirmation through a comment or finding comfort from connecting with a familiar friend after a stressful experience. Some young people described social media as a preferred avenue of support over traditional routes such as parents or counselors. They talked about how they had been contacted with messages of support or solidarity by previously unknown social media users who were replying to a question or hashtag they had posted. Other adolescents talked more generally about the sense of reassurance that social media gave them by just knowing that there were others out there, e.g.: “you notice that there’s thousands all across the world in the same boat as you” (Singleton et al., 2016, p. 400).

Compromising Relationships: Conflict and Criticisms, Disconnecting

Social media also appeared to have a negative impact on connections, as shown across thirteen papers. Adolescents gave multiple examples of arguments, criticisms, and abuse all arising from social media. The most common examples of negative connections were bullying; some adolescents described first-hand experiences of receiving threats while others spoke more generally about a culture of bullying and hostility online between peers. Adolescents described an atmosphere of criticism and negativity during some interactions. Sometimes arguments could be triggered by disagreements online, while another paper gave an example of real-life offline incidents spilling over into social media (Calancie et al., 2017). Such behavior was often linked by adolescents to anonymity, impulsivity, disinhibition, and miscommunication, factors that were deemed more prevalent in online than offline communication.

Adolescents also referred to a more passive form of relationship difficulty on social media, that of feeling disconnected. Participants spoke of the burden of being tied to former friends or ex-partners through social media. A lack of attention in the form of feedback could leave some feeling rejected or un-liked (Calancie et al., 2017). Some participants referenced a feeling of “frustration, loneliness and paranoia” that they were being talked about online or excluded from something occurring somewhere else on social media, while other adolescents described feeling “excluded” when witnessing photos of friends getting together without them (Scott et al., 2019, p. 3; Weinstein, 2018, p. 3608).

Second Meta-theme: Identity

The second theme, identity, described the way adolescents were either supported or frustrated on social media in their efforts to move towards certain identity states, which, when met are likely to have positive implications for well-being (Vignoles et al., 2006). Adolescents in 13 of the papers made comments that could refer to identity processes, describing aspects of social media that supported authenticity and self-esteem, provided life continuity, and allowed them to exhibit distinctiveness.

Supporting Identity Construction

Adolescents in 12 of the papers described how social media allowed them to express themselves in a way that accessed their true, authentic self. Authenticity was voiced by some as coming “out of their shell on Facebook” or putting “the self out there” (Best, Taylor, & Manktelow, 2015, p. 141; MacIsaac et al., 2018, p. 10). Authenticity on social media appeared to be facilitated by the various mediums available: the ability to write and edit thoughts before posting them, using mixed media (e.g., words and images) to capture a mood state, or through the privacy that some social media platforms afford (e.g., Snapchat; Throuvala et al., 2019). Three of these papers also referred to the role that social media audiences played in the expression process, with unknown spectators witnessing the expression of self, which in turn produced cathartic or empowering feelings for the author.

The opportunities available on social media to develop or grow one’s self-esteem was referenced by adolescents in six of the papers. Consistent with the literature that supports the association between self-esteem and well-being, adolescents described feeling “confident” in themselves, feeling “good about yourself” or helping to “build a positive self-image” with the feedback they received on their photographs, suggesting that social media appeared related to positive self-evaluation. (Jong & Drummond, 2016, p. 257; Bell, 2019, p. 68; Chua & Chang, 2016, p. 193).

Social media also appeared useful in terms of expressing distinctiveness, with adolescents in four papers detailing how social media allowed them to distinguish themselves from others. Some adolescents spoke about the purpose of photos as a way to “express who you are”, emphasizing the need to try and “be different in your photo” or “[stand] out from the crowd” (Bell, 2019, p. 67; MacIsaac et al., 2018, p. 9). In other instances, distinctiveness involved displaying material possessions, which could be used symbolically to display such features as wealth. Other adolescents discussed their excitement in sharing “new ideas” over social media or the enjoyment of discovering a peer’s secret talents through social media (Weinstein, 2018, p. 3607).

Some adolescents described how social media allowed them to track the continuity of their identity over time. Continuity was described as noticing how one’s personality had “developed” or “progressed” when looking back at old photos on social media or “curating a digital footprint”. These processes could be said to support well-being, as described by one author as eliciting “positive emotions related to a sense of identity affirmation” (Weinstein, 2018, p. 3611).

Frustrating Identity Construction

Identity construction could equally be frustrated, with possible negative implications for well-being. Eight of the 19 papers described ways that social media influenced attempts to present an authentic self-presentation. In one example, social media activity could lead to behaviors that adolescents later judged to be inauthentic, such as bullying or being mean to others, actions that they felt did not represent who they were offline (Singleton et al., 2016). Other people talked more generally of feeling suspicious of others who used photo editing tools, possibly to disguise who they were (Throuvala et al., 2019), or referenced how it was possible to deliver communications more “sneakily” via forms of social media rather than honestly face to face (Vermeulen, Vandebosch, & Heirman, 2018, p. 88). In other examples, adolescents described creating a safe and acceptable social media form of themselves, by checking with themselves or others, before posting, whether their expressive post was in keeping with their social media character.

Six papers described how social media could have a negative impact on self-esteem, sometimes directly. Participants described how repeated self-scrutiny, before sharing selfies, could mean that “self-esteem, like confidence, is gone…down the hill” (Bell, 2019, p. 67). Consistently across six of the papers, adolescents appeared to base their self-worth on the feedback they received. This process went significantly beyond making them feel happy or sad, as not having a photo sufficiently liked, or not receiving enough positive comments, meant that friends are communicating that one is “ugly” (Chua & Chang, 2016, p. 193). Edited selfies were a way to shore up likes, which represented units of measurement, despite there being no clear guidance on how many likes constituted enough to reach a feeling of fulfillment. This so-called “heightened sensitivity to social information” was seen as having a detrimental impact on some adolescents’ sense of self-worth (Bell, 2019, p. 69).

Third Meta-theme: Learning

The theme of learning describes how adolescents’ social media use either supported or obstructed education. Education and opportunities to learn are often considered necessary components of well-being, providing the necessary tools and skills to achieve in life, creating a protective factor against psychosocial adversity, and enhancing self-efficacy and self-esteem (Mihálik et al., 2018; Pajares, 2006). Participant views relating to learning were coded in eight papers.

Promoting Learning and Inspiration

Adolescents described how social media could operate as a “window to the world”, with practical uses for assisting in homework. Specifically, the live nature of social media appeared enticing, and it was seen as “broadening; it’s interesting, it’s adding new stuff” (Throuvala et al., 2019, p. 169). Social media was described repeatedly as promoting learning through the breadth and depth of information available (Weinstein, 2018). It also allowed adolescents to become tuned into issues of politics and social justice, such as the #BlackLivesMatter movement. Adolescents also referenced how social media inspired them in other areas of learning, such as fashion, fitness, and presentation skills (Bell, 2019; Chua & Chang, 2016; Singleton et al., 2016).

Obstructing Learning

Five papers provided accounts of the ways that social media could potentially obstruct learning. The obstruction could occur through preoccupation with certain aspects of social media, such as investing time and effort pursuing likes or capturing the perfect photo, and through dominating the conversation at school or constantly intruding into lessons through its always-on aspect (Bell, 2019; Chua & Chang, 2016; MacIsaac et al., 2018). Others described how they found it difficult to spend quiet time alone to reflect, without the interruptions of certain social media notifications (Calancie et al., 2017). Adolescents could also be more explicit in naming cause and effect, stating that school attendance was problematic “after logging off at 4 am” and linking the distraction of social media to a fall in grades (Bharucha, 2018, p. 125).

Forth Meta-theme: Emotions

A fourth theme, emotions, described the ways that social media could impact emotional experiences, both positively and negatively. The subjective appraisal of one’s mood state is a central component of well-being, alongside cognitive appraisals of life satisfaction (Diener, 2000). References to appraisals of emotional experiences appeared across 18 of the papers.

Positive Effect on Mood

Adolescents in five studies described ways in which social media seemed to promote positive moods. Social media was described as lifting moods, producing feelings of excitement, happiness, being higher, or “just a way to make me feel better” (Throuvala et al., 2019, p. 169). Adolescents in these papers also described social media as being entertaining and a source of laughter. Adolescents described experiences similar to positive emotional contagion, where witnessing another emotional reaction produced a similar reaction: “Yeah, it [looking through social media] makes me feel happy. Seeing someone else happy kind of makes me happy” (Weinstein, 2018, p. 3607).

In a further six papers, adolescents described how they used social media to help regulate negative emotions. For example, adolescents described how they sought out social media opportunities to manage annoyance, anger, and sadness (Duvenage et al., 2020). Social media was frequently described as an antidote to “boredom” (Throuvala et al., 2019, p. 170). The most referenced form of emotional regulation was stress management, with adolescents in four papers describing social media as a tool that can help one unhook from busy, challenging lives: “If I’m having a stressful day or something- it’ll help me laugh and help me unwind a bit” (Weinstein, 2018, p, 3616).

Negative Effect on Mood

For many adolescents, however, social media represented a source of worry and pressure. In almost all papers (N = 16), adolescents described the ways that social media was associated with worries and fears, often about being judged or having behaviors scrutinized. Such behaviors could include updating a status, posting an opinion, or uploading a photo of themselves. Adolescents also spoke of the fear that others may be talking about them on social media or posting unflattering photos, with worry often associated with increased “checking” or “curiosity” regarding social media activity (Weinstein, 2018, p. 3603; Singleton et al., 2016, p. 398). When photos were posted, adolescents described frequently checking to see how well they had performed, with too few likes associated with frustration or embarrassment (Chua & Chang, 2016). Adolescents in three papers also described worry associated with perceived parental intrusion into their social media world, which they were keen to avoid: “It like gives me anxiety whenever my parents are like ‘okay, I’m gonna just like check something’ and they like actually check my computer history” (Burnette et al., 2017, p. 119).

Some adolescents expressed troubling thoughts about the frequency of their social media use, with papers describing a pattern of social media behavior as “dependent” “addicted” “compulsive” (O’Reilly et al., 2018, p. 8; Radovic et al., 2017, p. 9; Throuvala et al., 2019, p. 170; Singleton et al., 2016, p. 398). Adolescents expressed general concerns about the consequences of leaving digital artifacts, such as embarrassing photos or comments, material that could be duplicated and disseminated without the authors’ knowledge (Vermeulen et al., 2018). Social media also represented a source of pressure for several adolescents across studies. Adolescents in three papers spoke about the pressure to have social media, to the extent that not having social media was “unheard of” (Scott et al., 2019, p. 542). Not being on social media was linked to a belief that it would result in exclusion from offline social circles (Singleton, 2016). Pressures to share, stay connected (“in tune with my group”), and respond immediately to contacts were reported by adolescents (Bharucha, 2018, p. 123). Expectations to reply “immediately” to messages were linked by one author to feelings of distress (Calancie et al., 2017, p. 8). Similar expectations were repeatedly cited by adolescents as a barrier to switching off and getting to sleep: “Is there a way where I can justify leaving? Can I say ‘look, I’m tired?’ ” (Scott et al., 2019, p. 542).

A further way that adolescents linked social media to negative moods was through encountering upsetting content, which was reported in four studies through exposure to distressing images or posts. Three papers reported accounts of adolescents describing coming across graphic self-harm images or through reading accounts of others “expressing how depressed they are” (Weinstein, 2018, p. 3608; Radovic et al., 2017; Singleton et al., 2016). Upsetting content was also relational, such as seeing updates about former partners in new relationships (Calancie et al., 2017). Other papers described negative emotional contagion, whereby sad upsetting posts by others triggered similar feelings of being brought “down” or feeling “guilty for not helping” (O’Reilly et al., 2018, p. 5; Singleton et al., 2016, p. 400).

Discussion

A growing body of literature has linked the rise of social media use to a decrease in the well-being of adolescents. This paper sought to supplement existing reviews of quantitative, cross-sectional research, by appraising the qualitative literature that could answer the question: what are the views and experiences of adolescents of social media and its relationship to their well-being? This was accomplished through a systematic literature search and quality appraisal, followed by a thematic synthesis. Four themes emerged, namely connections, identity, learning, and emotions. Within each theme, complex and nuanced accounts of the relationships between adolescent social media use and well-being emerged.

Connections and Well-Being

The theme of connections was present in all but one of the 19 papers and accounted for a web of interpersonal relationships that adolescents built with peers across social media platforms. Adolescents in the reviewed studies cited connections as a central aspect of social media, where connections could be seen to encourage a context in which social support could be leveraged through creating and nurturing relationships. Taking a developmental lens, the creation of supportive peer connections can be viewed as part of the process of individuating and developing a network of healthy attachments from outside the family of origin (Lyons-Ruth, 1991). In adolescence, young people begin a process of exploration, in search of supportive peer bonds, thus reducing the reliance on the primary attachment figure. By mid-adolescence, these interactions with peers begin to encompass a wide variety of roles that persist throughout the lifespan (Allen & Tan, 2018). The review findings suggest that for many adolescents, forming and nurturing connections over social media may contribute to this individuation and development process. Future studies will be needed to explore how this varies by age and stage of adolescence.

At the same time, adolescents in several of the reviewed papers described how social media could be a hostile social context, in which existing relationships could be compromised through criticisms, conflict, and social media posts that led to the sense of exclusion and disconnection from friends. To some extent, these experiences reflect the variation that can occur in social processes offline. However, the adolescents’ accounts highlighted the unique contributory features of social media, including user anonymity, the greater possibility for miscommunication and misunderstanding, and the experience of peer evaluation through ‘likes’. Their accounts also identified the role that impulsivity and disinhibition could play in their negative relational experiences on social media. These findings are particularly relevant to the adolescent period because neurological developments during adolescence lead to increased risk-taking and impulsivity, as well as to increased sensitivity to environmental rewards, such as ‘likes’ (Griffin, 2017). Arguably, these features of adolescence interact with the nature of social media to magnify the nature and impact of negative relational experiences; for example, disinhibited and impulsive behaviors can be witnessed and fed back on by a substantially larger audience than would be possible offline.

What may differentiate adolescents in terms of well-being outcomes derived from connections on social media is less clear from the synthesis. However, attachment theorists have long suggested that the secure attachments that adolescents have with parents are important for the construction of healthy models of the self (Harter, 1990). It is plausible that differences in attachment styles influence the extent to which social media is experienced by adolescents as a supportive medium for developing connections or as a more problematic one, though this would need to be examined in future research.

Relatedly, current research has identified how perceived online social support is associated with higher levels of life satisfaction, which is proposed to mediate the relationship between social media use and well-being (Erfani & Abedin, 2018; Manago, Taylor, & Greenfield, 2012; Nabi, Prestin, & So, 2013; Oh, Ozkaya, & LaRose, 2014). Indeed, individuals who experience warm, satisfying, trusting relationships are more likely to report higher well-being than those with few close, trusting relationships (Ryff, 1989). While there exists a body of literature exploring the more extreme forms of relationship discord on social media, such as cyberbullying, researchers are at an early stage of investigating adolescents’ wider experiences of online interpersonal rejection and exclusion (Aboujaoude et al., 2015; Landau, Eisikovits, & Rafaeli, 2019).

Identity and Well-Being

In the second theme, social media appeared to be used to develop aspects of identity by adolescents across 13 papers. Adolescence has long been considered the period when identity work becomes a crucial task (Erikson, 1968). The current review supports this, with accounts of the types of identity work that adolescents can engage in on social media. Specific identity-supporting acts identified in this review appeared to cluster around recognized domains, such as displaying distinctive qualities from others, growing self-esteem and enhancing a sense of worth, and using historical posts (such as browsing old photos) to track continuity of the self over time (cf. Goossens, 2001). It has been proposed that the satisfaction of certain identity-motivated behaviors, such as those described here, has positive implications for well-being, whereas frustration of these activities typically has negative consequences (Vignoles, 2011). Positively, some adolescents in this review revealed that they used social media to express “authenticity”, sometimes in the presence of a supportive, anonymous audience who were capable of witnessing and encouraging identity expression, a practice that has been associated with attaining validation and relief (Bazarova & Choi, 2014). Conceptually, the role of the audience in identity construction connects to that of “multi-voiced identities”; the idea that identity exists in the words and minds of many, instead of a single-voiced phenomenon (White, 2000).

Alongside the apparent benefits, adolescents in the review also described how identity work could have negative well-being implications, notably from social media behaviors that were later judged to be inauthentic or incongruent with who they were offline. Some adolescents also described a strong level of self-censorship in their behavior by appraising what is acceptable to broadcast to others; an awareness that may potentially pull adolescents in the opposite direction from expressing an authentic self in an attempt to ensure popularity. While these developmental challenges may be universal, social media appears to have introduced a proliferation of opportunities to curate identity and present it to a wider audience, thus potentially increasing the experiential intensity and well-being consequences. Furthermore, as mentioned above, adolescents’ increased risk-taking, impulsivity, and sensitivity to environmental rewards (Griffin, 2017) appear to interact with this environment to magnify these experiences. For example, photos and status updates may be quickly seen by large audiences and prove difficult to erase if regretted (Dowell, 2009).

From an emotional well-being perspective, incoherence between publicly posted, aspirational identity and the internally felt one has been theoretically attributed to psychological difficulties encompassing low mood and self-worth (Rogers, 1961). Such assumptions have been broadly supported in related literature that has associated the well-being of older adolescents with the accuracy of the information they choose to convey about themselves on social media, i.e. the degree of authenticity of their self-presentation. Inauthentic self-presentation has been found to be associated with low self-esteem and social anxiety, while authentic self-presentation was associated with more positive emotional outcomes (Twomey & O’Reilly, 2017). There appears, however, a dearth of literature that explores the long-term consequences of inauthentic presentation on social media, particularly for younger users. Understanding the long-term implications is relevant, as pressure to present an acceptable self on social media in early adolescence may hasten identity foreclosure, meaning forgoing the exploration of alternative roles and identities (Gardner & Davis, 2013). Overall, learning to negotiate experiences of feeling unwanted, un-liked, ignored, and rejected has always represented a complex emotional challenge, and this is a process that is likely to be intensified on social media (Leary, 2015). Although coping strategies vary, some adolescents have described how sharing tricky experiences with family, friends, and helping professionals can contribute to feelings of relief and belonging (Landau et al., 2019).

Learning and Well-Being

The theme of learning captured adolescent social media use both in terms of supporting and obstructing learning and was referenced across eight of the papers. Learning is an established marker of well-being, particularly in youth (Ozan, Mierina, & Koroleva, 2018). Adolescents across five of the papers described ways in which social media provided access to information that allowed them to explore subjects and spark interest in new ones. Equally, adolescents also described how social media appeared to dominate discussions in school and intrude into learning environments, providing examples of how grades have suffered as a result of social media overuse. Such examples appear to relate to the concept of an “attention economy” within a school, whereby social media, with its fast flow of eye-catching and distracting information, competes for attention in traditional educational settings, where deeper styles of attention are required for complex problems (Crogan & Kinsley, 2012). Such disruptions to learning fit with the theoretical literature, lending support to the displacement hypothesis, which suggests that time on social media replaces other, health-enhancing behaviors (Liu, Wu, & Yao, 2016; Suchert, Hanewinkel, & Isensee, 2015). Others, however, have recognized the potential value and opportunities inherent within social media when integrated into education, such as using social media within classroom settings to augment communication and collaboration (Gikas & Grant, 2013). A key difference, therefore, concerns whether social media represents an intrusion from outside the classroom or a tool deliberately harnessed to aid education.

Emotions and Well-Being

Adolescents in eighteen studies described several different examples of how social media impacted emotions or hedonic well-being. This type of moment-to-moment emotional appraisal, along with a cognitive appraisal of life satisfaction, combine into what is commonly referred to and measured as subjective well-being, where higher levels of pleasant affect (e.g., contentment) lead to greater well-being (Diener, 2000). As adolescence is often characterized by the increased occurrence, range, and intensity of emotional encounters, it is perhaps unsurprising that accounts of emotional experiences on social media featured in almost all of the reviewed studies. Social media appeared to provide a prominent stage in which a wide range of emotional challenges can occur and be enacted.

Adolescents across five papers discussed the role that engaging in social media activities has on eliciting positive emotions, such as feeling “happy” and “better” through being part of an entertained audience. These experiences are consistent with a conceptualization of social media as entertainment, designed to make its audience feel happy, engaged, released from pressure, and offering a temporary escape from reality. However, such notions can contrast with the possible negative long-term impact of media consumption (Bartsch, & Oliver, 2017; McQuail, 2010; Vorderer & Reinecke, 2015). Aside from positive emotion, adolescents in the current review described how social media can create a surveillance-like culture, in which they worry about missing out on social news or events, or more pertinently, becoming the subject of social news. Additionally, sources of pressure and worry were identified as coming from the perceived need to connect and respond to others with immediacy, suggesting more active patterns of engagement, though not necessarily ones driven by pleasure, but rather by a pressure to conform and reply. For example, some considered it “impolite” to not respond or felt they “have to reply” suggesting a discourse of social media etiquette in which socially accepted judgments about expectations and transgressions may drive adolescents to certain unhelpful communication patterns, having an impact on worry, distress, and sleep (Weinstein, 2018, p. 3613; Throuvala et al., 2019, p. 169).

While emotional stimulation can provide developmental opportunities, it also can increase vulnerability to adaptational difficulties relevant to well-being and mental health. Emotion regulation, namely how one controls, experiences, and expresses emotions as they unfold over a very brief period has been proposed to play a vital role in how adolescents approach such challenges (Opitz, Gross, & Urry, 2012; Quoidbach, Mikolajczak, & Gross, 2015). Moreover, this is particularly relevant to the adolescent stage, as emotion regulation abilities are in the process of developing during this time (Guyer, Silk, & Nelson, 2016). Some adolescents in the reviewed articles appeared to be trying to use social media to support emotion regulation; for example, they provided examples of using social media to respond to emotions such as anger or boredom. Social media is a comparatively new setting in which emotion regulation has been considered, and the majority of studies thus far have involved adult participants (Blumberg, Rice, & Dickmeis, 2016). Future research may benefit from considering social media’s role in both helping and hindering adolescents develop skills in emotion regulation.

In terms of practical social media guidance, evidence suggests that parental responses to help adolescents manage emotional experiences need to be adapted to their age and developmental level. For example, while direct interventions appear effective in younger children (e.g., providing instructions), adolescents can prefer indirect influences, such as discussing emotion regulation strategies, since these provide a better match for their developing cognitive and self-regulatory competencies, and desire for autonomy (Riediger, & Klipker, 2014). Such findings may help develop social media guidance that moves beyond restrictive and instructive screen-time management, to a more informed and developmentally appropriate dialogue for older adolescents.

Limitations and Implications for Future Research

The findings of this review are limited in several respects that would benefit from being addressed in future research. Firstly, in terms of increasing the depth of understanding, future research may benefit from utilizing qualitative approaches to generate theory, and from exploring alternative methods of data collection. For example, researchers may wish to explore in vivo data collection techniques, exploring the impacts of social media in real-time rather than reflections at a later date, which can be influenced by reporting bias.

The lack of attention to age and developmental stage in participants represents a limitation of the current research. The developmental stage is salient, as, during adolescence, youth will typically go through significant physical, psychological, and behavioral changes as well as experience external social changes, all of which will impact perceptions of what constitutes well-being (Rigby, Hagell, & Starbuck, 2018). Future research may wish to adopt a developmental lens when considering adolescents’ reports of well-being issues, in terms of both content and capacity to reflect on certain topics. Furthermore, developing a greater understanding of the roles that gender, ethnicity, and culture may play would also be helpful. Regarding the issue of accessing adolescent perceptions of well-being, studies may benefit from contextualizing their design and questions to encourage adolescents to discuss facets of well-being in a way that makes sense to them, thus increasing validity, and navigating potential issues regarding understanding and taboo.

This area would also likely benefit from quantitative studies that can explore the generalization of, and possible variation in, the issues raised by adolescents in this review over larger samples, across cultures, gender, and ages. These studies may wish to move towards process models, allowing researchers to tease apart the relative influence of potential factors (Hayes, 2017). Longitudinal or, where feasible and ethical, experimental designs, could allow a degree of temporal order or causality to be established. Furthermore, given that social media use appears to have the potential to have both positive and negative effects on wellbeing, across all the identified themes, research that seeks to further understanding the moderators and mediators that influence the nature of the effects of social media would be helpful.

Conclusion

Despite a surge in interest regarding the relationship between social media use and well-being, relatively few studies have attempted to capture the views and experiences of adolescents, which are vital to understanding any proposed relationships. The current review sought to redress this balance by reviewing and synthesizing the related qualitative literature. Nineteen studies were identified in which young people shared their views and experiences of social media and well-being. The thematic meta-synthesis revealed four themes relating to well-being: connections, identity, learning, and emotions. Within each theme, adolescents described the social and psychological drivers that appeared relevant to their well-being, in both positive and negative terms. These findings demonstrate the numerous sources of pressures and concerns that adolescents experience, which appear related to active social media use and hedonic well-being. Striking too, were how adolescents seemed motivated to use social media in relation to aspects of eudaimonic well-being, such as to construct aspects of their identity, learn, and build social connections. Taken together, the findings suggest that well-being and social media are related by a multifaceted interplay of factors including, thoughts, emotions, behaviors, and external narratives that influence aspects of use. Future research may wish to explore some of these factors quantitatively, to further examine how the relationship described here generalize and are moderated.

References

Aboujaoude, E., Savage, M. W., Starcevic, V., & Salame, W. O. (2015). Cyberbullying: Review of an old problem gone viral. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(1), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.011.

Allen, J. P., & Tan J. S (2018). The multiple facets of attachment in adolescence. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds) Handbook of attachment (pp. 399–415). Guilford Press.

Atkins, S., Lewin, S., Smith, H., Engel, M., Fretheim, A., & Volmink, J. (2008). Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: Lessons learnt. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-21.

Bartsch, A., & Oliver, M. B. (2017). Appreciation of meaningful entertainment experiences and eudaimonic well-being. In L. Reinecke & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of media use and well-being: International perspectives on theory and research on positive media effects (pp. 80–92). Routledge.

Bazarova, N. N., & Choi, Y. H. (2014). Self-disclosure in social media: Extending the functional approach to disclosure motivations and characteristics on social network sites. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 635–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12106.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Bell, B. T. (2019). “You take fifty photos, delete forty-nine and use one”: A qualitative study of adolescent image-sharing practices on social media. International Journal of Child–Computer Interaction, 20, 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcci.2019.03.002.

Best, P., Manktelow, R., & Taylor, B. (2014). Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review. Children and Youth Services Review, 41, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.001.

Best, P., Taylor, B., & Manktelow, R. (2015). I’ve 500 friends, but who are my mates? Investigating the influence of online friend networks on adolescent wellbeing. Journal of Public Mental Health, 14(3), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-05-2014-0022.

Bharucha, J. (2018). Social network use and youth well-being: A study in India. Safer Communities, 17(2), 119–131. https://doi.org/10.1108/SC-07-2017-0029.

Blumberg, F. C., Rice, J. L., & Dickmeis, A. (2016). Social media as a venue for emotion regulation among adolescents. In S. Y. Tettegah, Emotions and technology: Communication of feelings for, with, and through digital media. Emotions, technology, and social media (pp. 105–116). Academic.

Bondas, T., & Hall, E. O. (2007). Challenges in approaching metasynthesis research. Qualitative Health Research, 17(1), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732306295879.

Burnette, C. B., Kwitowski, M. A., & Mazzeo, S. E. (2017). “I don’t need people to tell me I’m pretty on social media:” A qualitative study of social media and body image in early adolescent girls. Body Image, 23, 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.09.001.

Calancie, O., Ewing, L., Narducci, L. D., Horgan, S., & Khalid-Khan, S. (2017). Exploring how social networking sites impact youth with anxiety: A qualitative study of Facebook stressors among adolescents with an anxiety disorder diagnosis. Cyberpsychology. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2017-4-2.

Chua, T. H. H., & Chang, L. (2016). Follow me and like my beautiful selfies: Singapore teenage girls’ engagement in self-presentation and peer comparison on social media. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 190–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.011.

Coyne, S. M., Rogers, A. A., Zurcher, J. D., Stockdale, L., & Booth, M. (2020). Does time spent using social media impact mental health?: An eight year longitudinal study. Computers in Human Behavior, 104, 106160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106160

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). (2018). CASP Qualitative Checklist. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/.

Crogan, P., & Kinsley, S. (2012). Paying attention: Towards a critique of the attention economy. Culture Machine. https://tinyurl.com/u28jo47.

Davis, K. (2012). Friendship 2.0: Adolescents’ experiences of belonging and self-disclosure online. Journal of Adolescence, 35(6), 1527–1536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.02.013.

Dickson, K., Richardson, M., Kwan, I., MacDowall, W., Burchett, H., Stansfield, C., Brunton, G., Sutcliffe, K., & Thomas, J. (2018). Screen-based activities and children and young people’s mental health: A Systematic Map of Reviews. EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education, University College London. http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34.

Dowell, E. (2009). Clustering of Internet risk behaviours in a middle school student population. Journal of School Health, 79, 547–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00447.x.

Duvenage, M., Correia, H., Uink, B., Barber, B. L., Donovan, C. L., & Modecki, K. L. (2020). Technology can sting when reality bites: Adolescents’ frequent online coping is ineffective with momentary stress. Computers in Human Behavior, 102, 248–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.024.

Erfani, S. S., & Abedin, B. (2018). Impacts of the use of social network sites on users’ psychological well-being: A systematic review. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 69(7), 900–912. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24015.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. Norton.

Finfgeld-Connett, D. (2010). Generalizability and transferability of meta-synthesis research findings. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66, 246–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05250.x.

Gardner, H., & Davis, K. (2013). The app generation: How today’s youth navigate identity, intimacy, and imagination in a digital world. Yale University Press.

Gikas, J., & Grant, M. M. (2013). Mobile computing devices in higher education: Student perspectives on learning with cellphones, smartphones and social media. The Internet and Higher Education, 19, 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2013.06.002.

Griffin, A. (2017). Adolescent neurological development and implications for health and well-being. Healthcare, 5, 62–76. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare5040062.

Goossens, L. (2001). Global versus domain-specific statuses in identity research: A comparison of two self-report measures. Journal of Adolescence, 24, 681–699. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2001.0438.

Guyer, A. E., Silk, J. S., & Nelson, E. E. (2016). The neurobiology of the emotional adolescent: From the inside out. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 70, 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.037.

Haidt, J., & Allen, N. (2020). Scrutinizing the effects of digital technology on mental health. Nature, 578, 226–227. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00296-x.

Harter, S. (1990). Causes, correlates, and the functional role of global self-worth: A life-span perspective. In R. J. Sternberg & J. Kolligan Jr. (Eds.), Competence considered (pp. 67–98). Yale University Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications.

Heffer, T., Good, M., Daly, O., MacDonell, E., & Willoughby, T. (2019). The longitudinal association between social-media use and depressive symptoms among adolescents and young adults: An empirical reply to Twenge et al. (2018). Clinical Psychological Science, 7(3), 462–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702618812727.

Jong, S. T., & Drummond, M. J. N. (2016). Hurry up and ‘like’ me: Immediate feedback on social networking sites and the impact on adolescent girls. Asia–Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 7(3), 251–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2016.1222647.

Kelly, Y., Zilanawala, A., Booker, C., & Sacker, A. (2018). Social media use and adolescent mental health: Findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. EClinicalMedicine, 6, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2018.12.005.

Keyes, K. M., Gary, D., O’Malley, P. M., Hamilton, A., & Schulenberg, J. (2019). Recent increases in depressive symptoms among US adolescents: Trends from 1991 to 2018. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(8), 987–996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01697-8.

Lachal, J., Revah-Levy, A., Orri, M., & Moro, M. R. (2017). Metasynthesis: An original method to synthesize qualitative literature in psychiatry. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, 269. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00269.

Landau, A., Eisikovits, Z., & Rafaeli, S. (2019). Coping strategies for youth suffering from online interpersonal rejection. In Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii international conference on system sciences. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/59656.

Leary, M. R. (2015). Emotional responses to interpersonal rejection. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 17(4), 435. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.4/mleary.

Long, H. A., French, D. P., & Brooks, J. M. (2020). Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Research Methods in Medicine and Health Sciences, 1(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/2632084320947559.

Liu, M., Wu, L., & Yao, S. (2016). Dose–response association of screen time-based sedentary behavior in children and adolescents and depression: A meta-analysis of observational studies. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(20), 1252–1258. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095084.

Lyons-Ruth, K. (1991). Rapprochement or approachment: Mahler’s theory reconsidered from the vantage point of recent research on early attachment relationships. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 8, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079237.

MacIsaac, S., Kelly, J., & Gray, S. (2018). ‘She has like 4000 followers!’: The celebrification of self within school social networks. Journal of Youth Studies, 21(6), 816–835. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2017.1420764.

Manago, A. M., Taylor, T., & Greenfield, P. M. (2012). Me and my 400 friends: The anatomy of college students’ Facebook networks, their communication patterns, and well-being. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 369. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026338.

Mihálik, J., Garaj, M., Sakellariou, A., Koronaiou, A., Alexias, G., Nico, M., Nico, M., de Almeida Alves, N., Unt, M., & Taru, M. (2018). Similarity and difference in conceptions of well-being among children and young people in four contrasting European countries. In G. Pollock, J. Ozan, H. Goswami, G. Rees & A. Stasulane (Eds.), Measuring youth well-being (pp. 55–69). Springer.

McQuail, D. (2010). Mass communication theory: An introduction (6th Ed., pp. 420–430). Sage.

Nabi, R. L., Prestin, A., & So, J. (2013). Facebook friends with (health) benefits? Exploring social network site use and perceptions of social support, stress, and well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(10), 721–727. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0521.

Odgers, C. L., Schueller, S. M., & Ito, M. (2020). Screen time, social media use, and adolescent development. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, 2(1), 485–502. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-devpsych-121318-084815.

Oh, H. J., Ozkaya, E., & LaRose, R. (2014). How does online social networking enhance life satisfaction? The relationships among online supportive interaction, affect, perceived social support, sense of community, and life satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.053.

ONS. (2017). Social networking by age group, 2011 to 2017. https://tinyurl.com/yc9lhjdk.

Opitz, P. C., Gross, J. J., & Urry, H. L. (2012). Selection, optimization, and compensation in the domain of emotion regulation: Applications to adolescence, older age, and major depressive disorder. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6, 142–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00413.x.

Orben, A., & Przybylski, A. K. (2019). The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nature Human Behaviour, 3(2), 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0506-1

O’Reilly, M. (2020). Social media and adolescent mental health: The good, the bad and the ugly. Journal of Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2020.1714007 Advanced online publication.

O’Reilly, M., Dogra, N., Whiteman, N., Hughes, J., Eruyar, S., & Reilly, P. (2018). Is social media bad for mental health and wellbeing? Exploring the perspectives of adolescents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 23(4), 601–613. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104518775154.

Ozan, J., Mierina, I., & Koroleva, I. (2018). A comparative expert survey on measuring and enhancing children and young people’s well-being in Europe. In G. Pollock, J. Ozan, H. Goswami, G. Rees & A. Stasulane (Eds.), Measuring youth well-being. Children’s well-being: Indicators and research (Vol. 19). Springer.

Pajares, F. (2006). Self-efficacy during childhood and adolescence. In T. Urdan & F. Pajares (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 339–367). IAP-Information Age Publishing.

Quoidbach, J., Mikolajczak, M., & Gross, J. J. (2015). Positive interventions: An emotion regulation perspective. Psychology Bulletin, 141, 655–693. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038648.

QSR International Pty Ltd. (2015). NVivo (released in March 2015). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home.

Radovic, A., Gmelin, T., Stein, B. D., & Miller, E. (2017). Depressed adolescents’ positive and negative use of social media. Journal of Adolescence, 55, 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.002.

Rideout, V. J., & Robb, M. B. (2019). The common sense census: Media use by tweens and teens. Common Sense Media. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/research/2019-census-8-to-18-key-findings-updated.pdf.

Riediger, M., & Klipker, K. (2014). Emotion regulation in adolescence. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 187–202). The Guilford Press.

Rigby, E., Hagell, A., & Starbuck, L. (2018). What do children and young people tell us about what supports their wellbeing? Evidence from existing research. Health and Wellbeing Alliance. http://www.youngpeopleshealth.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Scoping-paper-CYP-views-on-wellbeing-FINAL.pdf.

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069.

Scott, H., Biello, S. M., & Woods, H. C. (2019). Identifying drivers for bedtime social media use despite sleep costs: The adolescent perspective. Sleep Health, 6, 539–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2019.07.006.

Singleton, A., Abeles, P., & Smith, I. C. (2016). Online social networking and psychological experiences: The perceptions of young people with mental health difficulties. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 394–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.011.

Suchert, V., Hanewinkel, R., & Isensee, B. (2015). Sedentary behavior and indicators of mental health in school-aged children and adolescents: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine, 76, 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.026.

Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8, 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

Throuvala, M. A., Griffiths, M. D., Rennoldson, M., & Kuss, D. J. (2019). Motivational processes and dysfunctional mechanisms of social media use among adolescents: A qualitative focus group study. Computers in Human Behavior, 93, 164–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.012.

Tong, A., Flemming, K., McInnes, E., Oliver, S., & Craig, J. (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12, 181. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-181.

Twenge, J. M., Joiner, T. E., Rogers, M. L., & Martin, G. N. (2018). Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among US adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clinical Psychological Science, 6, 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617723376.

Twenge, J. M. (2020). Why increases in adolescent depression may be linked to the technological environment. Current Opinion in Psychology, 32, 89–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.06.036.

Twomey, C., & O’Reilly, G. (2017). Associations of self-presentation on Facebook with mental health and personality variables: A systematic review. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 20, 587–595. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0247.

Vermeulen, A., Vandebosch, H., & Heirman, W. (2018). Shall I call, text, post it online or just tell it face-to-face? How and why Flemish adolescents choose to share their emotions on- or offline. Journal of Children and Media, 12(1), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2017.1386580.

Vignoles, V. L., Regalia, C., Manzi, C., Golledge, J., & Scabini, E. (2006). Beyond self-esteem: Influence of multiple motives on identity construction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 17, 251–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.2.308.

Vignoles, V. L. (2011). Identity motives. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 403–432). Springer.

Vorderer, P., & Reinecke, L. (2015). From mood to meaning: The changing model of the user in entertainment research. Communication Theory, 25(4), 447–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12082.

Weinstein, E. (2018). The social media see-saw: Positive and negative influences on adolescents’ affective well-being. New Media and Society, 20(10), 3597–3623. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818755634.

White, M. (2000). Reflecting Team work as definitional ceremony revisited. In Reflections on narrative practice: essays and interviews. Dulwich Centre Publications.

Acknowlegement

We extend our gratitude to the authors of the original studies for bringing forth the perspectives of young people.

Preregistration

The review protocol including review question, search strategy, inclusion criteria data extraction, quality assessment, data synthesis was preregistered and is accessible at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=156922.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MS conceived of the study, participated in its design, coordination, interpretation of the data and drafted the manuscript; LH participated in the design and interpretation of the data; FWJ participated in the design and interpretation of the data. All authors read, helped to draft, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shankleman, M., Hammond, L. & Jones, F.W. Adolescent Social Media Use and Well-Being: A Systematic Review and Thematic Meta-synthesis. Adolescent Res Rev 6, 471–492 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-021-00154-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-021-00154-5