Abstract

This paper examines the vision and intent of New Zealand’s Māori education policy, Ka Hikitia, and its implications on the daily lives of Māori students in New Zealand’s education system. Extensive information on the secondary school experiences of rangatahi Māori (youth) have been gathered—originally in 2001 and at the end of 2015, through Kia Eke Panuku: Building on Success (Kia Eke Panuku: Building on Success is a secondary school reform initiative that is fully funded by the Ministry of Education, however, this paper represents the view of the authors and is not necessarily the view of the Ministry). Based on the messages from these two points in time, the paper concludes that the promises of Ka Hikitia are yet to be fully realised. If we, as educators, are to leave a legacy of more Māori students fashioning and leading our future, the need for the system to step up still remains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Ministry of Education takes its role in reducing the disparities of outcomes between Māori and non-Māori students across the education system very seriously. The responsibility of the system to ensure that Māori students enjoy and achieve educational success as Māori was clearly outlined in the launch of a major and ground-breaking strategy and vision: Ka Hikitia: Managing for Success 2008–2012. This strategy was refreshed and relaunched as Ka Hikitia: Accelerating Success 2013–2017. We are now in the final months of the refreshed strategy and it is therefore timely to examine the impact of this significant policy, vision and strategy on the lived experiences of these students. In this paper, we examine the vision and intent of Ka Hikitia. We hypothesise that, if the intent of this policy was being realised, then Māori students in New Zealand’s education system would be reporting their ‘enjoyment and achievement of education success as Māori’. Extensive information on the secondary school experiences of rangatahi Māori gathered in 2015 through Kia Eke Panuku: Building on SuccessFootnote 1 is presented. This is compared with what Māori students told Te KotahitangaFootnote 2 in 2001 leading to the conclusion that that the system has yet to fully step up as intended by Ka Hikitia.

Ka Hikitia: Stepping Up to Reduce Disparities

The Ministry of Education website tells us that Ka Hikitia—Accelerating Success is “our strategy to rapidly change how the education system performs so that all Māori students gain the skills, qualifications and knowledge they need to enjoy and achieve education success as Māori” (Ministry of Education 2015). Ka Hikitia is defined as “to step up, to lift up or to lengthen one’s stride” and challenges educators with, “stepping up how the education system performs to ensure Māori students are enjoying and achieving education success as Māori” (Ministry of Education 2015). The website spells out that, when this vision is realised, all Māori students will:

-

have their identity, language and culture valued and included in teaching and learning, in ways that support them to engage and achieve success;

-

know their potential and feel supported to set goals and take action to achieve success;

-

experience teaching and learning that is relevant, engaging, rewarding and positive, and;

-

have gained the skills, knowledge and qualifications they need to achieve success in te ao (the world) Māori, New Zealand and the wider world.

The History of Ka Hikitia

The first Māori education strategy was launched in 1999 and had three main goals. They were:

-

to raise the quality of English-medium education for Māori;

-

to support the growth of high-quality kaupapa Māori education, and;

-

to support greater Māori involvement and authority in education.

That first strategy recognised that Māori educational success was a Ministry-wide responsibility. It created an environment that led to a range of new initiatives including: iwi (tribal) education partnerships; professional development programmes, such as Te Kotahitanga and Te KauhuaFootnote 3; the Whakaaro Mātauranga communications campaign (Te Mana—ki te TaumataFootnote 4) and the appointment, by the Ministry of Education, of more than 20 Pouwhakataki (Māori community liaison officers) throughout the country; additional Māori-medium schooling support; and various student engagement initiatives.

In 2005, the Ministry of Education was able to report that Māori students were showing some improvements in educational performance. They confirmed that new initiatives such as research projects and evaluations had been developed and were providing more information on student achievement and the Ministry’s iwi partnerships. In 2005, the 1999 Māori education strategy was republished to reaffirm the Ministry of Education’s commitment to Māori education.

In 2006, the first stage in the redevelopment of the Māori education strategy: Ka Hikitia: Setting Priorities for Māori Education was published as an internal document within the Ministry, setting out the proposed Māori education priorities for the next five years of engagement with iwi and key education sector groups. Ka Hikitia: Setting Priorities for Māori Education contributed directly to the Tertiary Education Strategy 2007–2012. In 2008, Ka Hikitia—Managing for Success: The Māori Education Strategy 2008–2012 was released, combining the earlier priorities with goals, actions and targets and made available for public consultation. And, in 2013, Ka Hikitia—Accelerating Success 2013—2017 was released.

Effectiveness of Ka Hikitia

The effectiveness of Ka Hikitia has been evaluated by the Office of the Auditor General, the results published in a series of five reports (see Office of the Auditor-General 2012, 2013, 2015, 2016a, b). The Auditor General was reasonably positive regarding the intent and potential of Ka Hikitia—Managing for Success. She said “overall, I found reason to be optimistic that Ka Hikitia will increasingly enable Māori students to succeed” (Office of the Auditor-General 2013, p. 7) and concluded that Ka Hikitia holds the potential for making a difference for Māori because it “reflects the interests and priorities of Māori well, is based on sound educational research and reasoning, is widely valued throughout the education system, and has Māori backing” (ibid). Her final report endorses the need for the potential the policy holds, including an entire chapter entitled “Every school needs to implement Ka Hikitia” (2016a, b, p. 18).

However, the Auditor General was critical of the launch and introduction of the policy. The report states:

The Ministry of Education (the Ministry) introduced Ka Hikitia slowly and unsteadily. Confused communication about who was intended to deliver Ka Hikitia, unclear roles and responsibilities in the Ministry, poor planning, poor programme and project management, and ineffective communication with schools have meant that action to put Ka Hikitia into effect was not given the intended priority. As a result, the Ministry’s introduction of Ka Hikitia has not been as effective as it could have been.” (2013, p. 7)

Even more damning, in the view of the Auditor General, was the loss of opportunity for transformative change, seeded within the Ka Hikitia policy but unrealised: “There were hopes that Ka Hikitia would lead to the sort of transformational change that education experts, and particularly Māori education experts, have been awaiting for decades. Although there has been progress, this transformation has not yet happened” (2013, p. 7). In 2016, while there was evidence of changes within some schools, the overall conclusion of the Auditor-General was that “the implementation of Ka Hikitia was originally flawed by a slow and unsteady introduction by the Ministry of Education”; “Ka Hikitia was not effectively communicated to schools” and, in the words of a senior Ministry of Education official, “the implementation of Ka Hikitia was faulty because it relied too much on goodwill and devolved responsibility (2016, p. 19).

The Education Debt

As acknowledged by all, including the Office of the Auditor General, there is no ‘quick fix’ to addressing the disparity of educational outcomes within our system. In the words of Wolfe and Haveman (2001, p. 2) “the literature on the intergenerational effects of education is generally neglected in assessing the full impact of education”—in other words, it would be simplistic to believe that the cumulative effect of intergenerational practices cannot be undone through a single series of actions.

One of our challenges is in the identification of the impacts on educational practices across our history. Gloria Ladson-Billings (2006) spoke of the need to look past narrow measures of achievement gaps and to take a wider view of education debt. The achievement gap is defined as the disparity in educational outcomes between groups of students—in the United States this is the ‘gap’ between black students and white students, Latino and white students and recent immigrants and white students. In New Zealand, it is the ongoing disparity in the performance between Māori and non-Māori students, and Pasifika and New Zealand European students. Education debt is defined by Robert Havemen (cited in Ladson-Billings 2006, p. 5) as:

the foregone schooling resources that we could have (should have) been investing in (primarily) low income kids, which deficit leads to a variety of social problems (e.g. crime, low productivity, low wages, low labour force particpation) that require ongoing public investment.

Haveman goes on to say “this required investment sucks away resources that could go to reducing the achievement gap. Without the education debt, we could narrow the achievement gap.”

Ladson-Billings cautions that a focus on the achievement gap itself can provide misleading information, leading to misinformed solutions—a focus on the yearly fluctuations in achievement scores in particular achievement measures can show an improvement over time that disappears when new measures are brought in. She refers to trend data that show a reduction in disparity between black and white students (within the United States) in the 1980s and “the subsequent expansion of those gaps in the 1990s” (Ladson-Billings 2006, p. 5). The short-term gains from the educational interventions of the 1980s were not sustained, despite the educational initiatives and a concurrent narrowing of income differences between black and white families. Seeking solutions that focus only on the achievement gap will not create transformative and sustainable change, instead, as outlined by Ladson-Billngs, we need to address the impact of the historical, economical, sociopolitical and moral decisions and policies that have created an education debt over successive generations.

New Zealand’s Education Debt

The Ministry of Education acknowledges well-intentioned but disadvantageous actions taken over time in order to ‘address the problem’ of Māori under-achievement. Many of these responses have resulted in the Ministry (as a system) looking for a cause or a point of blame, and then seeking a solution. A brief history of system-level responses to Māori underachievement is outlined on the Ka Hikitia website (Ministry of Education 2015). It references the Chapple Report (Chapple et al. 1997) that concluded the differences in achievement for Māori students compared with non-Māori students was because of their socio-economic status rather than ethnicity and “there was therefore nothing significant about ‘being Māori’ that affected education success”. (Ministry of Education 2015). The Ministry state that these findings substantially affected the way we thought about education achievement of Māori and contributed to a prevalent ‘blaming’ attitude and an abdication of responsibility by some in education: ‘It’s their background, what can we do?’.

A decade later, the website states, the conclusions of the Chapple Report were significantly challenged. Richard Harker (2007) undertook a further analysis of the data used by Chapple et al. and concluded that ethnicity is a significant factor in achievement over and above socio-economic status. Harker found that controlling for both socio-economic status and prior attainment reduces, but does not eliminate, significant differences between the four ethnic groups studied in the Progress at School and Smithfield projects. Harker suggested that the explanation lies between the interface of schools and student ethnicity.

Likewise, Hattie (2003), using disaggregated reading test results prepared as norms for the asTTle assessment programme, identified that achievement differences between Māori and non-Māori remained constant regardless of whether the students attended a high or low decile school. From this data, Hattie concluded that it is not socio-economic differences that have the greatest effect on Māori student achievement because these differences occurred at all levels of socio-economic status. Hattie concluded that the evidence pointed more to the major issue being the relationships between teachers and Māori students. The voices of Māori students and their teachers, gathered in 2001 (Bishop and Berryman 2006), supported these conclusions.

Subsequently, the Ministry presented an analysis across the best evidence syntheses (Alton-Le 2003; Biddulph et al. 2003; Mitchell and Cubey 2003; Timperley et al. 2006) that revealed education system performance has been persistently inequitable for Māori learners, citing the following contributors:

-

low inclusion of Māori themes and topics in English-medium education,

-

fewer teacher-student interactions,

-

less positive feedback,

-

more negative comments targeted to Māori learners,

-

under-assessment of capability,

-

widespread targeting of Māori learners with ineffective or even counterproductive teaching strategies (such as the ‘learning styles’ approach),

-

failure to uphold mana Māori in education,

-

inadvertent teacher racism,

-

peer racism,

-

mispronounced names and so on.

The Ministry also report the conclusion drawn by internationally renowned Harvard professor, Courtney Cazden, who, in 1990, after working with teachers in New Zealand, highlighted how deeply entrenched such disadvantageous, differential treatment is within the beliefs and practice of many New Zealand teachers. In most cases, this is not conscious prejudice, but part of a pattern of well-intended but disadvantageous treatment of Māori students.

As can be seen, the Ka Hikitia policy and strategies were introduced with an acknowledgement that successive and ongoing underachievement by Māori students required a full system response. In the words of the Education Review Office (ERO): “achieving equity and excellence of education outcomes for all New Zealand’s children and young people is the major challenge for our education system” (2016, p. 5). In order to contribute to achieving equity, the main evaluative question underpinning ERO reviews is now: How effectively does this school respond to Māori students whose learning and achievement needs acceleration? ERO’s school reviews, national evaluations and the research that underpins their latest School Evaluation Indicators show that when schools accelerate student achievement for Māori, achievement of all students accelerates as well (Education Review Office 2016a, b).

As we approach the final year of the implementation of this second iteration of Ka Hikitia, the 2013–2017 refresh, it is timely to consider what Māori students are experiencing, and what changes have we seen in Māori student experiences between 2001 and 2015. The following section presents the voices of senior Māori students, within New Zealand schools, talking of their experiences in 2015. The issues raised by these students are then compared with the experiences of Year 9 and 10 Māori students who spoke of their schooling experiences in 2001 (Bishop and Berryman 2006).

Enjoying and Achieving Education Success as Māori

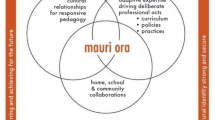

Kia Eke Panuku: Building on Success is a school reform initiative, operating in 93 secondary schools across New Zealand from 2014 through to the end of 2016. The kaupapa (central purpose) of Kia Eke Panuku was: Secondary schools giving life to Ka Hikitia and addressing the aspirations of Māori communities by supporting Māori students to pursue their potential. Kia Eke Panuku staff worked with school communities to understand and explore the Ka Hikitia vision: Māori students enjoying and achieving education success as Māori. Kia Eke Panuku found a great deal of confusion and uncertainty about how to interpret, let alone implement strategies to address, the central Ka Hikitia vision of: Māori students enjoying and achieving education success as Māori.

To gain understandings and provide some guidance for school communities, Kia Eke Panuku sought input from two groups. The first group comprised eight experienced educational experts (both Māori and non-Māori). The second group comprised over 150 senior Māori students from 58 secondary schools who had been identified by their schools as having enjoyed and achieved education success as Māori. Neither group worked towards a definitive definition or application of the phrase: Māori students enjoying and achieving education success as Māori, but rather worked to produce a set of ideas as starting points for ongoing reflection and sense-making by school communities.Footnote 5 Both groups participated only after following appropriate ethical consent processes. Consents were received from the adults themselves or in the case of minors after receiving parental and school consents.

Success as Māori as Described by the Expert Advisory Group

The Expert Advisory Group employed a group-brainstorm and collaborative prioritisation technique.Footnote 6 Their analysis concluded that schools could support tamariki-mokopuna on their journey towards success as Māori when they fostered and encouraged the following principles:

-

Living confidently—with affinity to whakapapa and at ease with a growing cultural competence in language, tikanga and identity.

-

Connected to and in harmony with the people, the environment and systems around about them.

-

Articulate and confident in expressing thoughts, feelings and ideas.

-

Skilled in building and navigating relational spaces.

-

Thinking respectfully and critically about the world and ideas.

-

Achieving qualifications from school and wider life that lead to future options and choice.

Procedure for Engaging with Successful Māori Students

To gather Māori students’ views on success as Māori, Kia Eke Panuku hosted a series of nine hui (meetings run following Māori cultural procedures), on marae (iwi cultural spaces) across New Zealand. These hui were held after the completion of the school year with up to three successful senior Māori students (nominated by their schoolFootnote 7) accompanied by one adult from the school. Most frequently the adults involved a member of the school’s Senior Leadership Team but also included teachers, whānau (family) and iwi members.

In the interview process, students were asked three questions that they had received prior to the day, thus allowing prior opportunities to think about and talk about with other adults and peers. The accompanying adult (from their school) posed the following questions in order:

-

What have been your successes in this school?

-

Who has helped you with this success?

-

In your experience, what does Māori students enjoying and achieving education success as Māori mean?

The tapes were transcribed and a thematic analysis of the transcripts was undertaken employing a grounded theory approach.

Success as Māori’ as Described by Māori students

Despite each hui being totally independent of the others, there was remarkably high consistency of experiences across the nine hui. Across all Māori students and across all groups, common experiences and understandings were shared. The following ten themes emerged:

-

Being able to resist the negative stereotypes about being Māori

-

Having Māori culture and values celebrated at school

-

Being strong in your Māori cultural identity

-

Understanding that success is part of who we are

-

Developing and maintaining emotional and spiritual strength

-

Being able to contribute to the success of others

-

Experiencing the power of whanaungatanga

-

Knowing, accepting and acknowledging the strength of working together

-

Knowing that you can access explicit and timely direction

-

Being able to build on your own experiences and the experiences of others

These themes were understood as strongly inter-related. For example, the strongest message from these students was that to be successful as Māori within the school system, they had to be able to resist and overcome other people’s low expectations and negative stereotypes about them being Māori. Many articulated this as an area where adults and non-Māori could and should be supporting them. Māori students clearly understood that their success required more than their own personal strengths, achievements, values and connections. Some Māori students directly attributed their success to the support they had received from a school environment where their own culture and values were explicitly celebrated, modelled and thus made more acceptable. This was essential to being able to be strong as Māori, rather than believing they had to compromise their own cultural identity by trying to pass as some one else. Understanding that success was a part of who they were and what other Māori were, or could be, required their being emotionally and spiritually strong. These students understood that at times this had not been the case for them, nor was it the case for many of their peers, including those friends and whānau some of whom, a number shared, had resorted to suicide.

Many of these students talked about being the first of their family to attain success, whether it was cultural success, in the arts, languages, academic and/or sporting success and whether it was at a school, regional, national or international setting. Many students talked about their success across a number of these indicators and across the range of these settings.

Some talked about not having seen themselves as successful until fairly recently. Across all of the groups, students clearly articulated that their personal success was fully intertwined with their contribution to the success of others. Being able to relate to others in a whanaungatanga or familial way, meant that they understood and took strength from working together. They understood that by working together, they would be more able to do things on their own in the future. They all talked about benefitting from being provided with timely and explicit guidance and direction which had helped them to build upon their own experiences but also the experiences of others.

While there is some distinct overlap between the views of the Expert Advisory Group and the students, there are also some marked differences. Generally, the students’ views of success as Māori are very encouraging. As articulated within Ka Hikitia, identity, language and culture are important indicators within a broad, holistic view of success, particularly success as Māori. What is less encouraging is that today’s students are still facing very similar challenges to students from over a decade ago when Māori students’ schooling experiences were gathered in 2001.

Student Views from 2001

In 2001, in conjunction with the genesis of Te Kotahitanga, a number of participants within five school communities were interviewed. These included the principal, teachers, whānau members and students who were identified by the schools as being engaged in learning and those not engaged in learning. The themes of these students’ discourses are summarised within Culture Speaks (see Bishop and Berryman 2006, pp. 254–255). Given that Te Kotahitanga involved research, ethical requirements were sought from the beginning of the project and these were maintained throughout. In this paper we have used previously published material only.

For Māori students, both those identified by their schools as engaged and those as not engaged, being Māori in secondary school was a negative experience (p. 254). As with our students in 2015, students in 2001 were also aware of negative stereotypes about Māori. They believed that many teachers overtly, negatively stereotyped Māori students, with some teachers being covertly racist. They felt that teachers expected them to misbehave and were constantly looking for misbehaviour (and finding misbehaviour that was often ignored in other students) and, likewise, teachers ignored opportunities to recognise good behaviours.

In 2015, our successful Māori students reported that, where it occurred, having Māori culture and values celebrated and modelled at their school had contributed to their success. In 2001, students discussed a range of issues that made their daily lives difficult such as having their names mispronounced or not being allowed to wear their taonga (cultural treasure often in the form of pounamu/greenstone pendants), or even having them cut from around their necks and confiscated. They also believed and gave examples of how schools were using Māori iconography and language in a tokenistic way that was belittling of their culture rather than valuing of it.

Both groups of students were positive about their own potential for success. In 2015, the students articulated that success was part of who they are as Māori, not that they achieved despite being Māori. While students in 2001 talked about their negative experiences within schooling, they had high expectations of schooling and teachers and had high aspirations for their own achievement towards gaining employment and contributing to their whānau. The authors concluded that “despite reporting that their experiences in education were overwhelmingly awful, year after year, these students understood and were still optimistic about the possibilities that education offered them” (Bishop and Berryman 2006, p. 255).

The 2015 students believed they had a sense of agency over their success. While they were highly appreciative of the support and encouragement provided by some teachers, they appeared to be able to look past less positive experiences and attitudes within other classrooms and to focus on the strength they derived when they experienced whanaungatanga in other parts of school or community life. The students in 2001 felt their success was dependent on their relationships with their teachers—they reported that their relationships with teachers was the most influential factor in their ability to achieve in classrooms. A very important difference between the Māori students in 2015 and the engaged Māori students in 2001, was that the engaged students in 2001 believed they had to give up their cultural identity in order to succeed at school and many of these students had done so.

Comparing Student Perceptions Between 2001 and 2015

A direct comparison between the two scenarios (Kia Eke Panuku in 2015 and Te Kotahitanga in 2001) is not possible. The sampling, the questions asked and the methodologies used are not the same. In 2001, Year 9 and 10 Māori students, identified by their schools as engaged or not engaged, participated in group-foccussed interviews as chat, and, although students were not told how they were identified, they had reached these conclusions for themelves. In 2015, senior students (mostly Year 12 and 13) were selected and the students were aware they had been identified as successful. However, neither group is representative of the whole-school, Māori student population.

In 2015, students were asked to describe Māori students enjoying and achieving education success as Māori. In 2001, students were asked to discuss their school experiences in terms of understanding what it would take to engage them in learning. While discussions identified barriers and enablers to student success, students were not directly asked about success as Māori.

There is also some variation in the methods used. In 2001, the students contributed from in-school groups (engaged students or non-engaged students) with an interviewer. In 2015, students spoke with others from their school, in front of supporters within a marae, cultural setting.

However, there is clear similarity in the messaging between the two groups. Both groups of students were aware of negative stereotyping around being Māori, with accompanying low expectations for achievement and for behaviour. The Year 9 and 10 students in 2001 appeared vulnerable to the impact of individual teachers, the more senior and confidently successful students in 2015 were able to look past the actions of individual teachers and draw on the strength of others, both peers and adults, both Māori and non-Māori, in their school or community.

In 2001, the Year 9 and 10 students were still optimistic about educational opportunities (Bishop and Berryman 2006, p. 255). Although the interviewed students were not individually tracked and we do not know how their personal educational experiences played out, the leaving statistics for all Māori students from that time do not hold an optimistic picture. In 2005, three years after these Year 9 and 10 students were interviewed and past the likely years when these students would be taking part in the national qualifications assessments, comparatively few Māori students left school with qualifications that would give them entry into tertiary study: 25% of Māori students left school with little or no formal qualification compared to 10% of European students (Loader and Dalgety 2008, p. 9). In 2005, only 33% of Māori students left school with a National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEAFootnote 8) Level 2 qualification or above, compared to 63% of European students.

Our 2015 students are in schools committed to making a difference for Māori students as evidenced by their willingness to participate in Kia Eke Panuku: Building on Success. These students were successful students, many of whom had just completed their secondary schooling and had gained entry to (some already had been accepted into) tertiary institutions. They were aware, though, that their stories, did not represent the experiences of all their Māori student peers, even in these schools. All of the 158 students who took part shared their concerns for those whose school experiences had not been positive and who had dropped out of school before achieving qualifications. And, school leaver achievement data would bear out their concerns—in 2014, 59% of Māori students left school with NCEA Level 2 or above compared to 81% of European students; in 2015, 62% of Māori students left school with NCEA Level 2 or above compared to 83% of European students (Ministry of Education 2016).

Impact of Ka Hikitia on Student Perceptions

We should expect to see that after seven years of Ka Hikitia, significant differences in both Māori students’ experiences of schooling and in their educational achievement.

The students in 2001 spoke of enduring negative stereotypes about being Māori within schools that impacted repeatedly on their daily lives. They talked openly (and heart-breakingly) about the low expectations for both academic success and positive behaviour from teachers. They talked about having to live with disrespectful and dismissive attitudes towards their language and their culture. Bishop and Berryman described the students’ school experiences as “overwhelmingly awful, year after year” (2006, p. 255) and this is supported by many of the teachers that were also interviewed. The school leaver achievement data for this cohort of students confirms that the daily lived experiences of these students had a direct and drastic impact on their achievement prospects. This is a damning indictment. However, the voices of these students tell of their experiences before the implementation of Ka Hikitia. Did it make a difference?

The reporting of these Māori students in 2015, a group of students who were finishing their schooling, had been or become successful within the system and had plans and pathways for the future, contains disturbing echoes of the experiences of the students of 2001. Our contemporary, successful Maori students talked about the need to overcome barriers and challenges to their success that did not seem to be experienced to the same degree by students who were not Māori. They also talked of negative stereotypes about being Māori (the most common theme from all nine hui) and the need to draw on emotional and spiritual strength to be able to withstand the stereotyping. They spoke of the need to be strong in their Māori cultural identity and, when it occurred, how affirming it was to have their cultural values celebrated in their school. These successful students also talked of their need to contribute to the success of other Māori students in their schools—a significant responsibility for these young people. While these students were successful, they knew that they were not the norm—many of their peers, their whānau and their friends—were not able to overcome the barriers and were not achieving the success that is the expected outcome of schooling. And, just like our cohort of 2001, school leaver data for the 2015 cohort shows that many (38%) Māori students will leave school without NCEA Level 2.

Students in 2015 had experienced most of their schooling with Ka Hikitia as the Māori success strategy—particularly all of their secondary schooling. The Auditor General was critical of how the first round of the policy, Ka Hikitia: Managing for Success 2008–2012 (Ministry of Education 2008) was implemented, but “found reason to be optimistic that Ka Hikitia will increasingly enable Māori students to succeed” (2013, p. 7). However, in 2016, following evaluation of both iterations of the policy, the Auditor General concluded that “progress on Māori education is still too slow. The disparity between Māori and non-Māori is too great, and too many Māori students are still leaving our school system with few qualifications” (Office of the Auditor-General 2016a, b, p. 13). The students’ voices from 2015, particularly poignant as we head into the eighth and final year of this strategy, seem to endorse the Auditor-General’s less-than-optimistic conclusion.

Conclusion: Addressing the Education Debt

If we listen to the voices of these students we could say that, between 2001 and 2015, we have made some advances in reducing the achievement gap. Although not closed, the achievement disparity between Māori and non-Māori students has narrowed. However, the daily experiences of Māori students within our schools has not dramatically improved—in 2015, Māori students still speak of a significant disjuncture between the promise of equity and excellence within our education system and their lived realities. The achievement gap may be narrowing according to our current measures however we still have a considerable way to go to address our education debt.

Should we address the education debt? The answer is, of course, yes. As Ladson-Billings says, “it is the equitable and just thing to do” (2006, p. 9). She goes on to give three other reasons to address the education debt: the impact on current educational achievement; the impact of the debt on the efficacy of current interventions; and, the potential to “forge a better educational future” (ibid., pp. 9–10).

Education debt has considerable impact on current educational achievement. In the financial world, we know that, when nations operate with large national debt, they need to draw from their current budget to service that debt. Ladson-Billings draws from this metaphor to conclude that “each effort we make toward improving education is counterbalanced by the ongoing and mounting debt that we have accumulated” (2006, p. 9).

While we continue to focus on the achievement gap, our education research and our interventions and initiatives continue to focus on mitigating educational inequality. We do not recognise, or at least acknowledge, that ongoing and intergenerational inequities (leading to an education debt) have significant impact on the efficacy of current interventions. We are in danger of continuing to look for new sticking plasters to cover wounds, without looking for the source of the infection that has led to the lesion.

Ladson-Billings shows the stark reality and impact of our stockpiling education debt. However, she does not leave us without hope, rather saying that addressing the debt gives us opportunities to potentially forge a better educational future.

While our students did not use the term education debt, they spoke of the challenges that living under the negative stereotyping of Māori, built up over successive generations, had on them and their peers. The message to educators, and to policy makers across the sector, is that a focus on improving achievement is not sufficient. Instead the promise of transformative change as outlined in the principles of Ka Hikitia is required to address the debt we owe these students. If we are to reap the benefits of Māori students fashioning and leading our future, and we must if our nation is to truly flourish, then ensuring the alignment of the sector to step up, continues to be the imperative.

Notes

Kia Eke Panuku: Building on Success is a secondary school reform initiative that is fully funded by the Ministry of Education, however, this paper represents the view of the authors and is not necessarily the view of the Ministry.

Te Kotahitanga (Unity of Purpose) is an iterative school reform initiative that emphasised the crucial importance of culturally responsive and relational pedagogies if Māori students were to engage with learning. Student experiences are reported in Culture speaks: Cultural Relationships and classroom learning (Bishop and Berryman 2006).

Te Kauhua is a project that supports school-based action research projects aimed at helping schools and whānau work together in ways to improve education for Māori.

Te Mana—ki te Taumata (Get there with learning) is a national information campaign launched earlier in 2016 to raise expectations of Māori achievement.

This information, with fuller details of the process followed and discussions undertaken, can be found on the Kia Eke Panuku website: http://kep.org.nz/student-voice/about-the-themes.

This information, with fuller details on the nomination and confirmation process are provided on the Kia Eke Panuku website: http://kep.org.nz/student-voice/about-the-themes.

National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) is the official secondary school qualification in New Zealand.

References

Alton-Lee, A. (2003). Quality teaching for diverse students in schooling: Best evidence synthesis. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Biddulph, F., Biddulph, J., & Biddulph, C. (2003). The complexity of community and family influences on children’s achievement in Aotearoa New Zealand: Best evidence synthesis. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Bishop, R., & Berryman, M. (2006). Culture speaks: Cultural relationships and classroom learning. Wellington: Huia Publishers.

Chapple, S., Jeffries, R., & Walker, R. (1997). Māori participation and performance in education: A literature review and research programme. Wellington: NZIER.

Education Review Office. (2016a). Accelerating student aachievement: Māori. Retrieved August 2, 2016, from http://www.ero.govt.nz: http://www.ero.govt.nz/how-ero-reviews/accelerating-student-achievement-maori/#why-maori-student-achievement.

Education Review Office. (2016b). School evaluation indicators: Effective practice for improvement and learner success. Wellington: Education Review Office.

Harker, R. (2007). Ethnicity and school achievement in New Zealand: Some data to supplement the Biddulph et al. (2003). Best Evidence Synthesis: Secondary analysis of the Progress at School and Smithfield datasets for the iterative Best Evidence Synthesis. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Hattie, J. (2003). Teachers make a difference. What is the research evidence? (pp 1–17). In Australian council for educational research annual conference on building teacher quality. Auckland: University of Auckland. https://cdn.auckland.ac.nz/assets/education/hattie/docs/teachers-make-a-difference-ACER-(2003).

Ladson-Billings, G. (2006). From the achievement gap to the education debt: Understanding achievement in U.S. schools. Educational Researcher, 35(7), 3–12.

Loader, M., & Dalgety, J. (2008). Students’ transitions between school and tertiary. Wellington: Demographic and Statistical Analysis Unit, Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education. (2008). Education Counts. Retrieved July 14, 2016, from Highest Attainment Numbers: https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/schooling/senior-student-attainment/school-leavers2/highest-attainment-numbers.

Ministry of Education. (2015). The Māori Education Strategy ka Hikitia. Retrieved from Ministry of Education: http://www.education.govt.nz/ministry-of-education/overall-strategies-and-policies/the-maori-education-strategy-ka-hikitia-accelerating-success-20132017/strategy-overview.

Ministry of Education. (2016). School leaver attainment. Retrieved July 16, 2016, from Education Counts: http://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/schooling/senior-student-attainment/school-leavers2/ncea-level-2-or-above-numbers.

Mitchell, L., & Cubey, P. (2013). Best evidence synthesis: Characteristics of professional development linked to enhanced pedagogy and children’s learning in early childhood settings. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Office of the Auditor-General. (2012). Education for Māori: Context for our proposed audit work until 2017. Wellington: Huia Publishers.

Office of the Auditor-General. (2013). Education for Māori: implementing Ka Hikitia—Managing for success. Wellington: Huia Publishers.

Office of the Auditor-General. (2015). Education for Māori: Relationships between schools and whānau. Wellington: Huia Publishers.

Office of the Auditor-General. (2016a). Education for Māori: Using information to improve Māori educational success. Wellington: Huia Publishers.

Office of the Auditor-General. (2016b). Summary of our education for Māori reports. Wellington: Huia Publishers.

Timperley, H., Fung, I., Wilson, A., & Barrar, H. (2006). Professional Learning and Development: A best evidence synthesis of impact on student outcomes. San Francisco: American Educational Research Association.

Wolfe, B., & Haveman, R. (2001). Accounting for the social and non-market benefits of education. In J. Helliwell (Ed.), The contribution of human and social capital to sustained economic growth and well-being (pp. 1–72). Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berryman, M., Eley, E. Succeeding as Māori: Māori Students’ Views on Our Stepping Up to the Ka Hikitia Challenge. NZ J Educ Stud 52, 93–107 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-017-0076-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-017-0076-1