Abstract

This research explores s-commerce users’ intentions to purchase and to share knowledge by incorporating ‘attitudes toward persuasion attempts,’ ‘ease of use,’ and ‘perceived usefulness’ into a social exchange theory model. A survey using an on-site purposive sampling technique was used to recruit the respondents, and an interception technique was used to approach the consumers. A total of 471 Korean consumers participated in this research. Based on 471 Korean social-commerce users, our results reveal that social exchange belief factors and a site’s usability affect user satisfaction, which subsequently affects users’ intentions to purchase and to share knowledge. In addition, attitudes toward persuasion attempts moderate the effect of satisfaction on users’ purchase intentions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A growing number of researchers are becoming interested in identifying factors that contribute to social-commerce (hereafter, s-commerce) users’ intentions to purchase and to share knowledge (Zhang and Benyoucef 2016). Scholars suggest that social exchange theory (SET) can provide useful insights for examining the relationships between s-commerce sites and their users (Chen et al. 2015; Choo and Petrick 2014; Salam et al. 1998). Some studies have drawn on SET (see, for example, Choo and Petrick 2014; Kim and Park 2013; Lin et al. 2014) in recent years; nevertheless, more attention should be focused on exploring the different dimensions of s-commerce sites that can contribute to consumers’ social exchange processes. S-commerce is defined as a business model that uses social media to support business-to-consumer and consumer-to-consumer online interactions and support transactions (Wu and Li 2017).

There are three research gaps in the current s-commerce literature. First, there is a gap in the current approaches used to analyze s-commerce users’ behavioral intentions. Approaches that emphasize SET beliefs may have overlooked the significance of virtual community platforms. However, approaches that focus on a system’s characteristics could undermine the relevance of s-commerce site users and user–user interactions. To build a successful virtual community, companies must have an effective virtual community platform and ensure that users believe that these platforms can promote friendly and meaningful exchanges between members (Lin et al. 2014; Tsai et al. 2011).

Second, studies on the influence of different dimensions of SET beliefs (i.e., trust, reputation, and reciprocity) have reported inconsistent results. For example, Jin et al. (2010) determined that reputation has a significant impact on consumer satisfaction. Shiau and Luo (2012) indicated that such inconsistency undermines the effectiveness of SET beliefs when examining consumers’ behavior regarding the use of s-commerce and thereby weakens SET.

Third, another area of online consumption research that warrants additional exploration relates to the effects of persuasion. Consumers have limited opportunities or may not be able to sample a product in an online environment; thus, a well-designed s-commerce site alone may not be sufficient to stimulate a consumer’s intentions to purchase or to share information with others (Wu 2013). An s-commerce user’s behavioral intentions might be conditioned by the consumer’s attitude toward the vendor’s persuasion attempts (Prendergast et al. 2010; Sparks et al. 2013). However, prior studies have not investigated the role of persuasion in conjunction with SET beliefs when examining s-commerce usage behaviors. The question of how to credibly persuade users also poses a knowledge gap for businesses, which are increasing their spending on digital platforms and online promotions (Brooke 2017; Hall 2017).

The purpose of this study is to explore s-commerce users’ intentions to purchase and to share knowledge by incorporating ‘attitudes toward persuasion attempts,’ ‘ease of use,’ and ‘perceived usefulness’ into an SET model. The main research question is as follows: ‘What are the determinants of a Korean s-commerce user’s satisfaction, intent to purchase, and intent to share knowledge?’ The objectives of this study are as follows. First, this study investigates whether a user’s attitude toward a vendor’s persuasion attempts moderates the relationships between satisfaction and intention to purchase and satisfaction and intention to share knowledge. Second, this study investigates the effect of SET beliefs (i.e., reputation, trust, and reciprocity) on consumers’ satisfaction with s-commerce sites. Third, this study investigates the effect of an s-commerce site’s usability (i.e., perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness) on user satisfaction.

2 Literature review

2.1 Social commerce

Laudon and Traver (2016) defined s-commerce as e-commerce that is enabled by online social relationships and social networks. Kim and Park (2013) referred to s-commerce as a new e-commerce business model driven by social media that facilitates the buying and selling of products and services. Liang and Turban (2011) suggested that s-commerce generally refers to the delivery of e-commerce activities and transactions through the social media environment, such as in social networks and by using Web 2.0 software.

The concept of s-commerce surfaced in the research literature in 2005 (Laudon and Traver 2016). In s-commerce, Web 2.0 applications and social media facilitate interactions among individuals in online communities and social networks to support consumers’ acquisition of products and services (Laudon and Traver 2016). S-commerce consumers are allowed and encouraged to create content, which makes these platforms more user-centric (Curty and Zhang 2011). Shin (2013) claimed that s-commerce makes use of various social technologies to allow customers to improve their shopping experience. The popularity of social technologies and platforms such as social networking sites (SNS) has been a driving force of the rise of s-commerce since its first appearance (Hajli and Sims 2015).

Although s-commerce is subset of e-commerce, the two platform types differ in several business and IT aspects, including users’ motives, businesses’ value creation models, challenges and issues, technologies, modes of interaction and communication, and platform design (Baghdadi 2016). For example, e-commerce deals only with consumers as individuals, whereas s-commerce addresses the community of consumers (Baghdadi 2016). In addition, the original e-commerce platforms provided mainly one-on-one relationships between a seller and a buyer and used a product-centric business model. In contrast, s-commerce provides customer-centric platforms and products and uses Web 2.0 technology to create new shopping trends in which customers leverage social networks for more efficient and effective transactions (Rad and Benyoucef 2011). To summarize, the most important characteristics of s-commerce include a consumer-centric community (Leitner and Grechinig 2008a), crowdsourcing (Leitner and Grechinig 2008b), multichannel shopping (Leckner and Schlichter 2005), revenue models (Leitner and Grechinig 2008b; Kang and Park 2009), and user-generated content (Ghose et al. 2009).

2.2 Research context

The online shopping environment is shifting to become a virtual social space for consumers. Electronic commerce’s (hereafter, e-commerce) share of total global retail sales is increasing at a steady pace and is expected to represent approximately 14.6% of total sales by 2020, which represents a significant expectation because e-commerce accounted for just 7.4% of total sales in 2015 (Social Commerce 2016). The growing importance of online social networks has contributed to this development. In 2010, the number of registered online social network users worldwide was approximately 1 billion. In 2016, the number of registered users had increased to approximately 2.3 billion (Social Commerce 2016).

Online social networks have transformed the online consumption environment from shopping and buying products online to an environment where consumers socially share their experiences, information, and reviews with an online community. Discussion forums and online communities are two important features and vehicles for s-commerce (Lin et al. 2014; Tsai et al. 2011). These features provide users with opportunities to participate, connect, and interact with one another via receiving and sharing information (Lu et al. 2010). Consumers have indicated that reading reviews and comments are two of the primary reasons for their use of social media, while receiving promotional offers followed as a close third (Social commerce 2016).

2.3 Social exchange theory and social exchange beliefs

To support this investigation, this study adopts SET as its overarching theory. SET proposes that social behavior is the result of an exchange process in which individuals weigh the potential risks (e.g., time and money) and benefits (e.g., friendship and support) associated with their social relationships (Blau 1964; McFarland and Ployhart 2015). According to SET, relationships between members of a community can evolve over time into trusting, loyal, and mutual commitments if the individuals follow certain ‘rules’ of exchange (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005). Moreover, when individuals act according to social norms, they typically expect reciprocal benefits (Blau 1964).

SET has been applied to online consumption studies and social network research (please refer to Appendix). SET is appropriate for these studies because the meaning and interpretation of social relationships has evolved through physical interactions that can be observed when users interact with one another online (McFarland and Ployhart 2015). An increase in the ownership of smart mobile devices in the West and in certain emerging markets, such as Korea, has also contributed to the social exchange process between online community users because these devices provide convenient access to online social networks that allow users to maintain online social relationships regardless of time and place (Mintel 2016).

Certain scholars who have studied consumers’ online consumption behavior by adapting SET have focused on SET-related factors that contribute to a user’s online experience, attitude, and/or satisfaction. Among the studies on consumer behavior individuals’ beliefs about online social exchanges have been considered as key antecedents of their online consumption experiences (Wu et al. 2014). The origin of social exchange belief-related dimensions is associated with the studies on beliefs and social relationships (Shiau and Luo 2012). A belief can be considered to be a cognitively based evaluation of some object that reflects the information available to the individual assessing the object at a given time (Line and Hanks 2016). Social exchange beliefs, therefore, refer to the individual’s evaluation of social exchange situations, such as whether or not to assist other online consumers.

Through examining social relationships and individuals’ beliefs about online social relationships, Shiau and Luo (2012) proposed a social exchange model that includes trust, reputation, and reciprocity as the three belief-related dimensions of social exchange that affect a user’s satisfaction with an online vendor. Furthermore, satisfaction can also affect a user’s intention to engage in group buying behavior. The model is particularly suitable for the context of this study because s-commerce marketers continue to seek better methods to engage with users and encourage users to interact with each other (Lin et al. 2014; Lin and Lu 2011). Although the influence of SET beliefs has been examined, the results were inconsistent. The body of knowledge regarding this specific topic can be enhanced through further exploring the effects of SET beliefs on consumers’ online behavioral intentions.

2.4 Perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and attitude toward persuasion attempts

To consider the significance of s-commerce platforms, this study incorporates perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use into a social exchange model. From a theoretical perspective, perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use can be incorporated into a social exchange model to examine consumers’ satisfaction with s-commerce, as it is a relatively new technology for consumers. Furthermore, an integrated model can capture users’ evaluations of the usability of an s-commerce site and users’ beliefs about a site’s ability to promote social exchange. Lin et al. (2014) and Tsai et al. (2011) indicate that building a successful virtual community requires a platform that encourages interaction and exchange between members; however, the system must also be usable. In addition, prior studies have confirmed the applicability of these factors in the context of e-commerce, online retailing, online social networks, and s-commerce (see, for example, Barkhi and Wallace 2007; Hsu and Lin 2008; Tsai et al. 2011).

The present study incorporates perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use into a social exchange model but does not integrate the technology acceptance module (TAM) with the social exchange model, as this research plans to focus on users who have previously used s-commerce sites. Therefore, although perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use might be important antecedents to s-commerce users’ continuous usage intentions (Lin et al. 2014), whether a user will accept or reject a new technology or social networking site is less critical in this study’s context. More importantly, there has been increasing concern about the comprehensiveness of the TAM, and it is perhaps more appropriate in an organizational context than in an everyday consumption context (López-Nicolás et al. 2008). For this reason, some research has borrowed variables without using the whole TAM (e.g., Abdullah et al. 2016; Negahban and Chung 2014; Ozturk et al. 2016). Furthermore, López-Nicolás et al. (2008) suggest that the TAM lacks the ability to account for social influence, which is essential to s-commerce.

Lastly, because an s-commerce site, such as Groupon, generally includes multiple vendors, a user’s attitude toward the vendor’s persuasion attempts may affect s-commerce users’ intentions to purchase and to share knowledge with other users (Prendergast et al. 2010). Attitudes toward persuasion may be particularly relevant in the context of this study because vendors on s-commerce sites want consumers to purchase their products and/or to share their knowledge and vendors’ product information with other users (Kim and Park 2013). In addition, vendors often compete with other vendors for consumers’ attention. Persuading online consumers can be challenging because it is easy for users to compare multiple offers in an online environment; however, they also have limited opportunities or are unable to sample a product in advance (Kim et al. 2010; Prendergast et al. 2010; Wu 2013). From a theoretical perspective, scholars have advocated for the inclusion of persuasion attempts as one of the communication methods in SET when examining the exchange process between two parties (Liao et al. 2010); nevertheless, additional studies must be conducted to explore this relationship. The inclusion of this factor can benefit the existing literature on s-commerce and SET because prior research has not fully explored the role of persuasion attempts in conjunction with SET beliefs when examining user satisfaction and usage behaviors.

3 Research framework and hypotheses development

3.1 Effects of social exchange beliefs on satisfaction

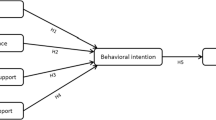

Based on related prior studies and the identified research gap, this study proposes its framework (Fig. 1). The first hypothesis concerns the relationship between trust and satisfaction. For this study, satisfaction is defined as a user’s affective overall appraisal of an s-commerce site (Dagger and David 2012). Trust refers to a consumer’s belief in the honesty of an s-commerce site (Wu 2013). Prior studies regarding online consumption have indicated that trust is an important factor for consumer satisfaction, as a physical interaction does not occur between the buyer and seller (Kim et al. 2009). Satisfaction is an important element for building a successful virtual community, such as an s-commerce site (Lin et al. 2014). Successful s-commerce sites have used multiple methods to ensure that users can trust their system and service, such as using a credible third party to complete online financial transactions (Chen and Barnes 2007; Lin et al. 2015). Wu (2013) indicates that online consumers’ belief that they can trust the seller is an important antecedent to their satisfaction. Based on the studies conducted by the aforementioned scholars, users who believe an s-commerce site is trustworthy are more likely to be satisfied. As a result, we hypothesize (H1) the following:

H1

Trust has a positive influence on users’ satisfaction with an s-commerce site.

Second, this study proposes that reciprocity will positively influence a user’s satisfaction with an s-commerce site. Reciprocity is defined as a user’s belief that the s-commerce site he/she visited has an environment such that sharing information will lead to a future request for information (Shiau and Luo 2012). In prior studies regarding social exchange, reciprocity has been found to represent an important element (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005; Golden and Veiga 2015; Khalid and Ali 2017). Because reciprocity among users and between users and sellers is important, s-commerce sites and online communities have developed methods of encouraging this behavior (Chu 2009; Jin et al. 2010; Kankanhalli et al. 2005), such as providing reward points to users who answer other users’ questions. Related studies have stressed the significance of the belief in reciprocity to a user’s satisfaction with an s-commerce site (Casaló et al. 2010; Shiau and Luo 2012). In other words, if a user believes that his/her efforts on behalf of other online users will be reciprocated in the future, then he/she will be more pleased with the s-commerce site. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis (H2):

H2

Reciprocity has a positive influence on users’ satisfaction with an s-commerce site.

Third, this study proposes that reputation positively affects a user’s satisfaction with an s-commerce site. Reputation is defined as the degree of a user’s belief that sharing information on an s-commerce site can increase his/her reputation (Shiau and Luo 2012). Prior studies regarding s-commerce have proposed that reputation is a key factor that affects a user’s experience and behavioral intentions (Jin et al. 2010, 2015; Kankanhalli et al. 2005; Lin et al. 2015). For example, studies regarding social identity in online communities suggest that certain individuals participate in these communities because it enhances their reputation and builds their online self-concept (Hsu and Lin 2008). Because an individual’s reputation is important for online social exchanges, online businesses and vendors have developed systems that provide buyers and sellers with more information regarding each user’s reputation, such as their honesty and level of knowledge (Lin et al. 2015). This study proposes that users will be more satisfied with their s-commerce site usage if they believe that sharing information on the site will improve their image (H3):

H3

Reputation has a positive influence on users’ satisfaction with an s-commerce site.

3.2 Effect of an s-commerce site’s usability on satisfaction

To investigate the effects of the usability of an s-commerce site, the first usability dimension variable that we examine is perceived ease of use. Perceived ease of use is defined as the degree to which a consumer believes that using a particular s-commerce site would be free from effort (Davis et al. 1989). In the context of s-commerce, online vendors have used different methods to ensure that their systems are easy to use because consumers may stop using their service if it is difficult to navigate (Ayeh et al. 2013; Yen et al. 2010). For example, when consumers plan their travel using consumer-generated media, such as TripAdvisor, the perceived ease of use has a direct effect on consumers’ site usage experiences (Ayeh et al. 2013). Consumers are more likely to form a positive evaluation of the site if they can learn to use the system within a short time. Prior studies regarding s-commerce have confirmed that perceived ease of use has a direct effect on user satisfaction (Wang 2014). Therefore, we propose hypothesis (H4):

H4

Perceived ease of use has a positive influence on users’ satisfaction with an s-commerce site.

The second usability dimension variable that is related to the usability of the s-commerce site examined in this study is the effect of perceived usefulness on user satisfaction. Perceived usefulness can be defined as the degree to which a consumer believes that using a particular s-commerce site would enhance his or her task, such as information gathering or performance (Davis et al. 1989). The effects of perceived usefulness have been tested and confirmed for multiple contexts that are related to s-commerce (Hess et al. 2014). For this reason, vendors have attempted to enhance their systems’ usefulness from the perspective of the user. Certain vendors provide personalized information based on a consumer’s prior consumption behavior and current location (Sun et al. 2014; Yen et al. 2010). Calisir and Calisir (2004) and Sun et al. (2014) have revealed that user satisfaction partially depends on the platform’s perceived usefulness. An online user’s expectations can be exceeded if he/she perceives that the s-commerce site is tailored to his/her needs. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis (H5):

H5

Perceived usefulness has a positive influence on users’ satisfaction with an s-commerce site.

3.3 Effects of satisfaction on behavioral intentions

This study proposes that user satisfaction affects the user’s intention to share knowledge with others and the user’s intention to purchase. A purchase intention is defined as a user’s desire to purchase from an s-commerce site (Deng and Li 2013). The intention to share knowledge refers to a goal-oriented desire to share knowledge about a product with others when participating in s-commerce activities (Erden et al. 2012). Prior studies regarding consumer behavior have confirmed that consumer satisfaction with the products they consume, such as food, affects their behavioral intentions to purchase these products and to recommend them to others (Um et al. 2006; Wan and Chan 2013). In addition, prior studies have confirmed that a positive relationship occurs between a user’s evaluation of an online community and his/her intention to participate in that community (Lin et al. 2014).

S-commerce network sites play a key role in bringing individuals together and facilitating relationship bonds or strong ties. If users have a strong positive evaluation of an s-commerce site, they will feel a strong desire to continuously engage with that site in the future (Lin et al. 2014). Um et al. (2006) and Wan and Chan (2013) propose that users are more likely to share their knowledge about a product and recommend it to others if they are highly satisfied with the s-commerce site (H6). In addition, Lin et al. (2014) confirm that users are more likely to make a purchase if they are pleased with the s-commerce site. We test the following two hypotheses (H6 and H7):

H6

S-commerce satisfaction has a positive influence on users’ intention to share knowledge.

H7

S-commerce satisfaction has a positive influence on users’ intention to purchase.

3.4 Moderating effects of attitude toward persuasion attempts

The final two relationships examined in this study consider that a user’s attitude regarding a persuasion attempt moderates the relationship between s-commerce user satisfaction and users’ behavioral intentions, i.e., intention to share knowledge and intention to purchase. For this study, an attitude toward a persuasion attempt is defined as the extent to which an s-commerce consumer modifies his/her intention toward a product because of an overall evaluation of a vendor’s persuasion attempt (Kenrick et al. 2005). Prior studies regarding consumer behavior have consistently shown that consumers perceive online consumption to be riskier than face-to-face transactions (Beldad et al. 2010). Furthermore, multiple vendors promote competition or similar products on s-commerce sites (Kim and Park 2013). For vendors to compete effectively, consumers must favorably perceive online vendors’ persuasion attempts, for example, perceiving vendor messages as credible (Hsieh et al. 2012; Sparks et al. 2013).

Studies have reported circumstantial evidence that supports the concept that a user’s attitude toward a vendor’s persuasion attempt moderates the relationship between satisfaction and behavioral intentions. In prior studies on s-commerce usage, satisfaction is an emotion-related construct that evaluates users’ attitudes toward social networking sites (Lin et al. 2014). Previous studies regarding consumers have determined that attitude moderates the relationship between the effects of emotional reactions and behavioral intentions (de Matos et al. 2009). The results of these studies indicate that a consumer’s attitude toward a vendor’s persuasion attempt might be able to moderate the relationship between s-commerce satisfaction and behavioral intentions. If a user has a positive attitude toward a vendor’s persuasion attempts, the user’s satisfaction with the s-commerce site will have a greater impact on the user’s behavioral intentions, such as his/her intentions to purchase and to share knowledge with other users. We hypothesize that users’ satisfaction will more significantly influence their intention to share knowledge (H8) and intention to purchase (H9) when they have higher positive attitudes toward the vendor’s persuasion attempts than when they have lower positive attitudes toward the vendor’s persuasion attempts.

H8

Satisfaction has a stronger positive influence on intention to share knowledge for users who have higher positive attitudes toward the vendor’s persuasion attempts.

H9

Satisfaction has a stronger positive influence on purchase intention for users who have higher positive attitudes toward the vendor’s persuasion attempts.

4 Research method

4.1 Sampling and data collection

To examine this study’s proposed framework, trained interviewers were used to collect data. The respondents were contacted at pre-selected locations, including internet cafes. The sampling area for the primary study included Seoul, South Korea. South Korea is ranked first in the world for active social network penetration, with 76% of the population using social networks (Social commerce 2016). Among the many cities in Korea, Seoul has the highest number of social network users. In addition, a sharp increase in the number of s-commerce users and firms has been observed (Kim and Park 2013). Numerous studies on consumer behavior and s-commerce have been conducted in Korea (e.g., Jin et al. 2010; Kim and Park 2013; Lee et al. 2011). An on-site purposive sampling method was used to recruit the participants, and an interception technique was used to approach the consumers. This sampling method was suitable because the population was impossible to identify. A complete directory of Korea’s s-commerce users is not available; therefore, it was not feasible to select participants randomly (Bhattacherjee 2012).

To qualify for the survey, respondents were required to be over 18 years of age and to have participated in s-commerce activities within the past 3 months. To ensure that participants understood the context of this study, a description of an s-commerce site and examples of s-commerce sites were presented to the participants at the beginning of the interview. Of the surveys that were returned, 471 were deemed usable (78.5%). The survey took place between June and July 2015. Table 1 provides the participants’ demographic information.

4.2 Measures and operational definitions

The participants completed a survey that included two sections. In the first section, participant demographics were collected. The second section included 38 statements regarding trust (Shiau and Luo 2012), reputation (Shiau and Luo 2012), reciprocity (Shiau and Luo 2012), satisfaction (Shiau and Luo 2012), perceived usefulness (Yen et al. 2010), perceived ease of use (Liao et al. 2010), intention to purchase (Kim and Park 2013), intention to share knowledge (Erden et al. 2012) and attitudes toward persuasion attempts (Prendergast et al. 2010). A five-point Likert-type scale was used to capture the items. The items for each variable are presented in Table 2.

5 Data analysis and results

5.1 Model measurement

IBM SPSS AMOS 24 was used to analyze the data. This study used a two-step approach to structural equation modeling (SEM) that was recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (1988). The following two items were removed because of low factor loadings: ‘Sharing my information on an s-commerce site, X, would enhance my personal reputation’ (reputation) and ‘I openly share my photo and camera-related experiences or know-how with community members’ (intention to share knowledge). The factor loadings of these items were 0.53 and 0.68, respectively. After these two items were removed, all of the loadings on the intended latent variables were significant and greater than 0.7 (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Additionally, the squared-multiple correlations supported the reliability of the items used. All the constructs had Cronbach’s alphas and composite reliabilities that were greater than the recommended threshold of 0.7, thereby supporting construct reliability (Hair et al. 2012).

The factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE) were used to examine convergent validity. AVE refers to the average variance that is shared between a construct and its measurement (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Table 3 indicates that the AVE values ranged from 0.61 to 0.76. These values confirmed the convergent validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Last, the discriminant validity was examined by comparing the AVE of each construct with the shared variances between each individual construct and all of the other constructs. The discriminant validity was confirmed because the AVE value for each construct was greater than the squared correlation between constructs.

5.2 Common method bias

Common method variance was checked using the marker variable technique. According to Lindell and Whitney (2001) and Craighead et al. (2011), the marker variable technique has performed better than other post hoc statistical techniques. In addition, this technique can be used to correct common method variance. A theoretically unrelated construct (marker variable, MV) was employed to adjust the correlations among the principle constructs (Lindell and Whitney 2001; Craighead et al. 2011). The present research selected the lowest positive correlation (r = 0.001) between the MV and one of the other variables. Using the equations provided by Menguc and Auh (2010), this study computed the adjusted correlations and their statistical significances (Grayson 2007). The intercorrelations among the constructs before and after the MV adjustment are shown in Table 3 (below the diagonal and above the diagonal, respectively). Out of the 36 correlations, this research found that the MV adjustment made no significant correlations nonsignificant and made no nonsignificant correlations significant. Lastly, the MV was included in the proposed model. These findings suggest that the relationships included in this study’s model are unlikely to be inflated due to common method bias.

5.3 Structural model

After the overall measurement model was determined to be acceptable, the structural model was tested. The model fit was good (χ2 = 1268.40; df = 471; χ2/df = 2.693; p < 0.001 RMSEA = 0.059; CFI = 0.942; NFI = 0.921; GFI = 0.923; AGFI = 0.901), and the analysis results for the proposed hypotheses are presented in Table 4. Hypothesis H1 was supported (t = 7.7; β = 0.32; and p < 0.001). Therefore, trust has a positive impact on Korean users’ satisfaction with s-commerce. Hypothesis H2 was also confirmed (t = 3.95; β = 0.21; and p < 0.001), which indicates that reputation has a positive impact on user satisfaction. In addition, Hypothesis H3 was supported (t = 2.36; β = 0.11; and p < 0.05), which suggests that reciprocity affects a user’s satisfaction.

Hypothesis H4 proposed that the perceived ease of use positively affects user satisfaction. The statistics supported this hypothesis (t = 2.73; β = 0.12; and p < 0.01). In addition, Hypothesis H5 was supported (t = 2.48; β = 0.12; and p < 0.05), which indicates that perceived usefulness affects user satisfaction. H6 and H7 were both supported (t = 4.78; β = 0.33; p < 0.001; t = 4.37; β = 0.31; and p < 0.001, respectively); therefore, user satisfaction has a positive effect on the intention to purchase and to share knowledge.

5.4 Moderating effects (H8 and H9)

To test the hypothesized moderating effects of attitude toward the vendor’s persuasion attempts, an invariance analysis of different groups was applied. The participants were divided into two groups (i.e., high and low positively inclined attitude groups) based on their mean scores. Participants who scored higher than the average composed the high positively inclined attitude group (N = 207), and those who scored below the average composed the low positively inclined attitude group (N = 265).

Initially, the structural models for the high and low positively inclined attitude groups were estimated without across-group constraints (i.e., unconstrained models; χ2 = 1647.449). Then, across-group constraints (i.e., constrained model; χ2 = 1767.009), in which the parameter estimates for the high and low expectation groups were constrained to be equal, were applied. Finally, a Chi square test comparing the unconstrained and constrained models was used to detect any moderating effects. The results showed some differences between users with high positively inclined attitude and users with low positively inclined attitude.

To examine H8, this study constrained the path between satisfaction and intention to share knowledge. The result showed that there was no difference between the high and low groups (χ2 = 1647.449, p > 0.05); therefore, H8 was not supported. In other words, attitude toward the vendor’s persuasion attempts cannot moderate satisfaction’s influence on users’ intention to share knowledge. To test H9, this study constrained the path between satisfaction and purchase intentions. The results showed a significant difference between the two groups (χ2 = 1656.336, p < 0.01); therefore, H9 was supported, which means that satisfaction has a stronger positive influence on purchase intention for users who have higher positive attitudes toward the vendor’s persuasion attempts.

6 Discussion and practical implications

There are three gaps in the current s-commerce literature. First, there is a gap in the current approaches used to analyze s-commerce users’ behavioral intentions. Second, studies on the influence of different dimensions of SET beliefs (i.e., trust, reputation, and reciprocity) have reported inconsistent results. Third, the effects of persuasion have not been fully explored. The following sections will elaborate on how this research might have narrowed these gaps.

6.1 Analyzing s-commerce users’ behavioral intentions

The results reveal that this study’s proposed model is appropriate. Prior studies related to online consumption have generally focused on the usability of platforms or the interactions between users. The former approach might undermine the importance of online social exchange, whereas the latter approach could overlook the significance of the platform. To contribute to the literature, this study incorporates the usability dimensions of technology into a social exchange model. The results of this study demonstrate that the satisfaction of s-commerce site users is not only built on social exchange beliefs but also depends on website designers’ understanding of the usability aspect of building virtual communities, such as enabling users to be more effective shoppers and providing clear instructions for making a purchase. In addition, these results reconfirm the importance of providing utilitarian value to online users (Ayeh et al. 2013; Sun et al. 2014; Wang 2014; Yen et al. 2010). This research may make some contributions to the s-commerce literature by incorporating ‘ease of use’ and ‘perceived usefulness’ into an SET model because such an approach offers a holistic perspective on the formation of consumer satisfaction with virtual communities.

6.2 Examining the influence of SET beliefs

The results of the data analysis support prior studies regarding SET beliefs. We discover that users are more satisfied with an s-commerce site if they believe it is honest, promotes reciprocal behavior, and can improve their reputation. More importantly, this study contributes to the debate regarding the effect of reputation on the users of s-commerce sites. Studies regarding trust and reciprocity have received more attention from scholars, and the results have been more consistent (Casaló et al. 2010; Chen and Barnes 2007; Lin et al. 2015; Wu 2013); however, although the influence of online reputation is valued by s-commerce sites (Lin et al. 2015), fewer studies have analyzed this factor, and the results of these studies have been less consistent (e.g., Jin et al. 2010; Shiau and Luo 2012).

The results of this study are consistent with those of Jin et al. (2010) and Hsu and Lin (2008) because reputation significantly affects the satisfaction of s-commerce users. S-commerce site users may seek to form and maintain a positive image and reputation for their online identity because they believe doing so will increase their opportunities to receive help when needed and receive better product offers in the future. Furthermore, helping other users could represent a method of improving one’s self-image, which is an important benefit of social networking sites (Ekinci et al. 2013). Therefore, when building a successful s-commerce site, site owners should promote user’s beliefs that they will be well recognized and well respected if they contribute to the online community.

6.3 Exploring the effect of persuasion

Multiple vendors sell their goods and services on s-commerce sites. Furthermore, successful s-commerce sites not only have more buyers but also attract more sellers. User evaluations of vendor persuasion attempts may represent a critical variable for sales performance and word-of-mouth referrals; however, prior studies regarding s-commerce have not sufficiently focused on the influence of attitude toward persuasion attempts (de Matos et al. 2009; Lin et al. 2014). Our results demonstrate that satisfaction with an s-commerce site may not be sufficient to stimulate purchase intentions. However, high satisfaction may be sufficient to affect the intention to share knowledge about the product because attitude toward persuasion attempts did not exert a moderating effect on the relationship between satisfaction and intention to share knowledge.

Two potential explanations are provided for the results of this study. First, the intention to share knowledge could be positive, neutral, or negative; therefore, s-commerce users might be willing to share their knowledge of a product as long as they are satisfied with the site. Therefore, whether users have positive attitude toward a vendor’s persuasion attempt does not moderate the effect of satisfaction on the intention to share knowledge. Second, according to Kang and Park (2009), attitudinal loyalty measures the consumer’s strength of feeling toward a product and/or brand. Behavioral loyalty measures the consumer’s actual behavior, such as purchasing behavior. Purchase intention is thought to require a greater commitment from consumers (Jeon and Hyun 2013); therefore, although consumers will share knowledge as long as they are satisfied with the site, they will not form an intention to purchase unless they have a positive attitude toward a vendor’s persuasion attempt. Because prior studies have not analyzed these two relationships, our explanations will require additional exploration.

6.4 Practical implications

Since the introduction of e-commerce, consumers have changed their behaviors according to the benefits that those behaviors provide, such as by comparing products online and reading reviews. Retailers have also adjusted their strategies and offers based on the development of technology and changing consumer behavior. E-commerce has multiple subset platforms that contribute to overall online sales growth. One of these platforms is s-commerce. Studies have shown that consumers who use s-commerce have several characteristics that marketers should be aware of. For example, they are often equipped with relatively high product knowledge and greater bargaining power because they can purchase from various channels. Additionally, they value convenience, and recommendations from peers, and they are not afraid to try different brands/products (Kim and Park 2013). Promoting products to online consumers is challenging for marketing managers because competition is intense. In addition, numerous barriers are observed to build a successful s-commerce site. This study presents three recommendations to practitioners who want to attract more consumers to use their social networks, social media, and s-commerce platforms.

First, this study’s results have shown that it is imperative for s-commerce providers to build a trustworthy platform for consumers. When site is built on trust and social exchange, its reputation attracts genuine and high quality contributions from users that are likely to maintain a long-term virtuous circle given user satisfaction and user intention. In other words, this platform should encourage users to behave in a reciprocal way. Furthermore, consumers like to be recognized for their input when they make a contribution, such as by earning progressive badge after writing a certain number of reviews and earning expert status on certain product categories. Practitioners who want to attract more consumers to their s-commerce sites should highlight their site’s ability to promote social exchanges among users and between users and vendors. These managers should stress that they have a transparent system that can allow users to build their reputations. In addition, managers should emphasize that site users are willing to help other users and behave reciprocally. Managers who oversee s-commerce sites can share reputable users’ testimonials regarding how they have shared or received offers from other users and vendors. Furthermore, if a feedback system is available, then practitioners should provide rewards, such as discounts and vouchers, to users who regularly assist other users and contribute to the community. All these factors contribute to the satisfaction of s-commerce site users, which subsequently affects their intention to purchase and to share knowledge. This implication can be applied to a range of online s-commerce platforms a key feature of s-commerce is social interaction (Xiang et al. 2016). Additionally, some marketing programs are quite universal in terms of setting. For example, in a typical loyalty scheme, consumers would win points after making a purchase or other nonmonetary contributions.

Second, this study’s results show that to satisfy users, s-commerce providers must carefully consider elements such as their platforms’ user-friendliness and utilitarian value. In other words, when developing an s-commerce site, practitioners should ensure that their platform is both easy to use and useful. This includes the platform’s ability to allow users to exchange information, the ability to search for deals, and the ability to effectively and productively make purchases. For example, 24-h online customer service teams can address users’ questions, thereby making the site easier to use. Well-designed one-click buying and price comparison functions are useful because these functions allow users to be more productive and efficient when shopping for deals and communicating with other users. Managers and retailers can also offer click-and-collect programs to online community members as an extra members-only benefit. In the UK, 83% of online shoppers said that they usually select the cheapest delivery option; hence, as many as 69% of online shoppers use click-and-collect (Mintel 2016).

Third, to further stimulate satisfied users to have stronger purchase intentions, vendors on s-commerce need to work on their persuasion techniques. Based on this result, vendors on s-commerce sites should improve their marketing communication strategies by utilizing their knowledge of consumers, products, and persuasion techniques. Identifying potential consumers through research, understanding the features of competitors’ products, and designing suitable communication messages are crucial for vendors to successfully sell their products. Because 95% of Internet users have made purchases online and many online users are members of loyalty programs (Mintel 2016), vendors on s-commerce platforms should be able to gain insight into how to persuade online users more effectively by studying data such as online traffic and click-through-rate. For example, studies have shown that price is often online consumers’ main concern. Because consumers can easily compare prices on s-commerce platforms; managers should highlight their products’ financial value (e.g., price and value-for-money) while also being aware of price promotion activities from competitors to maintain and attract potential consumers.

If an s-commerce site receives posting fees or commissions from vendors, s-commerce site managers may also want to help vendors improve users’ attitude toward a vendor’s persuasion attempt. Managers can contribute to the performance of vendors and the s-commerce site by providing training sessions for the design of effective communication messages, providing templates for the aesthetic presentation of products, and helping vendors understand users’ preferences. For example, Ebay offers suggestions and templates to assist vendors selling their products more effectively, while Amazon offers free delivery options for all Prime members even when customers are not purchasing from shops run by a third party.

7 Conclusion

7.1 Academic contributions and managerial implications

In conclusion, this study contributes to our understanding of the relationship between s-commerce and consumers in a virtual market context. This study adds new insights to the literature in several ways. First, it proposed and examined an extended SET model to investigate the factors that contribute to Korean users’ satisfaction with s-commerce sites and their behavioral intentions, i.e., intentions to purchase and to share knowledge. Second, previous studies’ findings on the effect of online persuasion have been mainly circumstantial. This research confirmed that a user’s attitude toward a vendor’s persuasion attempt moderates the relationship between satisfaction and intention to purchase but not the relationship between satisfaction and intention to share knowledge. Third, this study further examined the influences of SET beliefs (i.e., reputation, trust, and reciprocity) and s-commerce site usability (i.e., perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness) on consumers’ satisfaction with s-commerce sites. In addition to supporting their effects, we also compared our findings with results of previous studies.

This study also provides some insights to practitioners regarding marketing products in an online environment. First, to satisfy users, s-commerce platform managers must provide utilitarian benefits, such as ease of use, as well as social benefits, such as promoting users’ interaction with one another. Second, when communicating with potential customers, vendors on s-commerce sites must help users form positive attitudes regarding their persuasion attempts. In other words, vendors must be knowledgeable about consumers’ preferences, the characteristics of their products, and effective persuasion tactics.

7.2 Limitations and future studies

Although this study makes several contributions to the related literature, it also includes certain limitations. First, as of 2017, South Korea has more than one mobile device per mobile subscriber and 76% social network penetration, which makes it a suitable environment for this study. The sample of participants might be a reflection of online shoppers who use smartphones and connect to SNS in South Korea, which is better known for the early development of s-commerce than other parts of the world. Thus, South Korea; it is not representative of the worldwide population. To increase the generalizability of this study’s proposed framework, future research might consider doing multi-national studies. Researchers might want to test this study’s framework by including participants from other developed countries, such as the G8 countries, or other Asia–Pacific regions, such as Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan.

Second, most of this study’s participants were younger than 35 years old. Although younger consumers tend to use s-commerce more often than older consumers, the demand by older customers may increase in the future because of the recent increase in popularity of s-commerce among older consumers. A future study that focuses on older or aging consumers’ online behaviors or key psychographic characteristics would be valuable for academics and practitioners because this consumer segment has been growing, and the factors that contribute to their s-commerce usage behavior may differ from those of younger consumers. In particular, future research could consider incorporating perceived risks of shopping online into this study’s proposed framework when studying aging consumers’ behavioral intentions because aging consumers tend to evaluate risk differently than younger consumers (Le Serre and Chevalier 2012).

Third, this study collected data from Korean consumers using an on-site sampling method. Our approach has limitations in that it might not include individuals who may be more willing to respond to an online survey. Additionally, as Straub and Burton-Jones (2007) suggested, respondents to a self-administered questionnaire might inflate their responses due to social desirability. Future research on this topic might want to recruit participants by using online surveys and compare those findings with this study’s results. Furthermore, apart from measuring behavioral intentions, it will be useful to try to obtain data regarding consumers’ actual usage behavior as this removes the issues relating to participants’ tendency to inflate their responses when responding to self-administrated surveys.

References

Abdullah, F., Ward, R., & Ahmed, E. (2016). Investigating the influence of the most commonly used external variables of TAM on students’ perceived ease of use (PEOU) and perceived usefulness (PU) of e-portfolios. Computers in Human Behavior,63, 75–90.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modelling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin,103(3), 411–423.

Ayeh, J. K., Au, N., & Law, R. (2013). Predicting the intention to use consumer-generated media for travel planning. Tourism Management,35, 132–143.

Baghdadi, Y. (2016). A framework for social commerce design. Information Systems,60, 95–113.

Barkhi, R., & Wallace, L. (2007). The impact of personality type on purchasing decisions in virtual stores. Information Technology and Management,8(4), 313–330.

Beldad, A., Jong, M. D., & Steehouder, M. (2010). How shall I trust the faceless and the intangible? A literature review on the antecedents of online trust. Computers in Human Behavior,26, 857–869.

Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Social science research: Principles, methods, and practices. Textbooks Collection. Book 3. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/oa_textbooks/3.

Blau, P.M. (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life. Transaction Publishers.

Brooke, Z. (2017). The top 7-commerce trends from Meeker’s 2017 internet report. Retrieved December 26, 2017 from AMA’s website: https://www.ama.org/publications/eNewsletters/Marketing-News-Weekly/Pages/top-7-e-commerce-trends-from-meekers-2017-internet-report.aspx.

Calisir, F., & Calisir, F. (2004). The relationship of interface usability characteristics, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use to end-user satisfaction with enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. Computers in Human Behavior,20, 505–515.

Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Guinalíu, M. (2010). Antecedents and consequences of consumer participation in on-line communities: The case of the travel sector. International Journal of Electronic Commerce,15(2), 137–167.

Chang, M. K., Cheung, W., & Tang, M. (2013). Building trust online: Interactions among trust building mechanisms. Information and Management,50, 439–445.

Chen, Y.-H., & Barnes, S. (2007). Initial trust and online buyer behavior. Industrial Management and Data System,107(1), 21–36.

Chen, Y., Yan, X., Fan, W., & Gordon, M. D. (2015). The joint moderating role of trust propensity and gender on consumers online shopping behavior. Computers in Human Behavior,43, 272–283.

Cheung, C., Lee, Z. W. Y., & Chan, T. K. H. (2015). Self-disclosure in social networking sites—the role of perceived cost, perceived benefits and social influence. Internet Research,25(2), 279–299.

Choo, H., & Petrick, J. F. (2014). Social interactions and intentions to revisit agritourism service encounters. Tourism Management,40, 372–381.

Chu, K.-M. (2009). A study of members’ helping behaviors in online community. Internet Research,19(3), 279–292.

Craighead, C. W., Ketchen, D. J., Jr., Dunn, K. S., & Hult, G. T. M. (2011). Addressing common method variance: Guidelines for survey research on information technology, operations, and supply chain management. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management,58(3), 578–588.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management,31(6), 874–900.

Curty, R. G., & Zhang, P. (2011). Social commerce: Looking back and forward. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology,48(1), 1–10.

Dagger, T. S., & David, M. E. (2012). Uncovering the real effect of switching costs on the satisfaction-loyalty association. European Journal of Marketing,46(3/4), 447–468.

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: a comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science,35(8), 982–1003.

de Matos, C. A., Rossi, C. A. V., & Veiga, R. T. (2009). Consumer reaction to service failure and recovery: the moderating role of attitude toward complaining. Journal of Service Marketing,23(7), 462–475.

Deng, Q., & Li, M. (2013). A model of event-destination image transfer. Journal of Travel Research,53(1), 69–82.

Dwyer, C., Hiltz, S., & Passerini, K. (2007). Trust and privacy concern within social networking sites: A comparison of Facebook and MySpace. AMCIS 2007 Proceedings, 339.

Ekinci, Y., Sirakaya-Turk, E., & Preciado, S. (2013). Symbolic consumption of tourist destination brands. Journal of Business Research,66(6), 711–718.

Erden, Z., Von Krogh, G., & Kim, S. (2012). Knowledge sharing in an online community of volunteers: The role of community munificence. European Management Review,9(4), 213–227.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement errors. Journal of Marketing Research,18(3), 39–50.

Ghose, A., Ipeirotis, P. G., & Sundararajan, A. (2009). The dimensions of reputation in electronic markets. NYU Center for Digital Economy Research Working Paper No. CeDER-06-02.

Golden, T. D., & Veiga, J. F. (2015). Self-estrangement’s toll on job performance. The pivotal role of social exchange relationships with works. Journal of Management. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315615400.

Grayson, K. (2007). Friendship versus business in marketing relationships. Journal of Marketing,71(October), 121–139.

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,40(3), 414–433.

Hajli, N., & Sims, J. (2015). Social commerce: The transfer of power from sellers to buyers. Technological Forecasting and Social Change,94, 350–358.

Hall, J. (2017). 7 E-commerce trends to pay attention to in 20188. Retrieved December 26, 2017 from Forbes’s website: https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnhall/2017/11/19/7-e-commerce-trends-to-pay-attention-to-in-2018/2/#7a499bd286db.

Hess, T. J., McNab, A. L., & Basoglu, K. A. (2014). Reliability generalization of perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and behavioral intentions. MIS Quarterly,38(1), 1–28.

Hsieh, J.-K., Hsieh, Y.-C., & Tang, Y.-C. (2012). Exploring the disseminating behaviors of eWOM marketing: persuasion in online video. Electronic Commerce Research,12(2), 201–224.

Hsu, C.-L., & Lin, J. C.-C. (2008). Acceptance of blog usage: The roles of technology acceptance, social influence and knowledge sharing motivation. Information and Management,45(1), 65–74.

Jeon, S. M., & Hyun, S. S. (2013). Examining the influence of casino attributes on baby boomers’ satisfaction and loyalty in casino industry. Current Issues in Tourism,16(4), 343–368.

Jin, J., Li, Y., Zhong, X., & Zhai, L. (2015). Why users contribute knowledge to online communities: An empirical study of an online social Q&A community. Information and Management,52, 840–849.

Jin, B., Park, J. Y., & Kim, H.-S. (2010). What makes online community members commit? A social exchange perspective. Behaviour and Information Technology,29(6), 587–599.

Kang, Y. R., & Park, C. (2009). Acceptance factors of social shopping. Paper presented at the Advanced Communication Technology, 2009. ICACT 2009. In 11th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology.

Kankanhalli, A., Tan, B. C. Y., & Wei, K.-K. (2005). Contributing knowledge to electronic repositories: An empirical investigation. Management Information System Quarterly,29(1), 113–143.

Kenrick, D. T., Neuberg, S. L., & Cialdini, R. B. (2005). Social psychology: Unraveling the Mystery (3rd). Auckland, New Zealand: Pearson Education.

Khalid, S., & Ali, T. (2017). An integrated perspective of social exchange theory and transactional cost approach on the antecedents of trust in international joint ventures. International Business Review,26(3), 491–501.

Kim, J., Jin, B., & Swinney, J. L. (2009). The role of retail quality, e-satisfaction and e-trust in online loyalty development process. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services,16(4), 239–247.

Kim, J. U., Kim, W. J., & Park, S. C. (2010). Consumer perceptions on web advertisement and motivational factors to purchase in the online shopping. Computers in Human Behavior,26(5), 1208–1222.

Kim, S., & Park, H. (2013). Effects of various characteristics of social commerce (s-commerce) on consumers’ trust and trust performance. International Journal of Information Management,33, 318–332.

Laudon, K. C., & Traver, C. (2016). E-Commerce 2016: Business, Technology, Society: Pearson Higher Ed.

Leckner, T., & Schlichter, J. (2005). Information model of a virtual community to support customer cooperative product configuration. In Paper presented at the 11th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction.

Le Serre, D., & Chevalier, C. (2012). Marketing travel services to senior consumers. International Journal of Consumer Marketing,29(4), 262–270.

Lee, J., Park, D.-H., & Han, I. (2011). The different effects of online consumer reviews on consumers’ purchase intentions depending on trust in online shopping malls: An advertising perspective. Internet Research,21(2), 187–206.

Leitner, P., & Grechenig, T. (2008a). Consumer centric communities: Integrating community based features into online shops. Paper presented at the International Conference on Web Based Communities (IADIS).

Leitner, P., and Grechenig, T. (2008b). Social networking sphere: A snapshot of trends, functionalities and revenue models. Paper presented at the IADIS international conference on web based communities.

Liang, T.-P., & Turban, E. (2011). Introduction to the special issue social commerce: A research framework for social commerce. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 16(2), 5–14.

Liao, C., Chen, J.-L., & Yen, D. C. (2007). Theory of planning behavior (TPB) and customer satisfaction in continued use of e-service: An integrated model. Computers in Human Behavior,23(6), 2804–2822.

Liao, H., Liu, D., & Loi, R. (2010). Looking at both sides of the social exchange coin: A social cognitive perspective on the joint effects of relationship quality and differentiation on creativity. Academy of Management Journal,33(5), 1090–1109.

Lin, H., Fan, W., & Chau, P. Y. K. (2014). Determinants of users’ continuance of social networking sites: A self-regulation perspective. Information and Management,51(5), 595–603.

Lin, K.-Y., & Lu, H.-P. (2011). Why people use social networking sites: An empirical study integrating network externalities and motivation theory. Computers in Human Behavior,27, 1152–1161.

Lin, I.-C., Wu, H.-J., Li, S.-F., & Cheng, C.-Y. (2015). A fair reputation system for use in online auctions. Journal of Business Research,68, 878–882.

Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology,86(1), 114–121.

Line, N. D., & Hanks, L. (2016). The effects of environmental and luxury beliefs on intention to patronize green hotels: the moderating effect of destination image. Journal of Sustainable Tourism,24(6), 904–925.

López-Nicolás, C., Molina-Castillo, F. J., & Bouwman, H. (2008). An assessment of advanced mobile services acceptance: Contributions from TAM and diffusion theory models. Information and Management,45, 359–364.

Lu, Y., Zhao, L., & Wang, B. (2010). From virtual community members to C2C e-commerce buyers: Trust in virtual communities and its effect on consumers’ purchase intention. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications,9(4), 346–360.

McFarland, L. A., & Ployhart, R. E. (2015). Social media: A contextual framework to guide research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology,100(6), 1653–1677.

Menguc, B., & Auh, S. (2010). Development and return on execution of product innovation capabilities: The role of organizational structure. Industrial Marketing Management,39(5), 820–831.

Mintel. (2016). Digital trends spring- UK- March 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2017 from Mintel’s website: http://academic.mintel.com/display/747972/?__cc=1.

Negahban, A., & Chung, C.-H. (2014). Discovering determinants of users perception of mobile device functionality fit. Computers in Human Behavior,45, 75–84.

Ozturk, A. B., Bilgihan, A., Nusair, K., & Okumus, F. (2016). What keeps the mobile hotel booking users loyal? Investigating the roles of self-efficacy, compatibility, perceived ease of use, and perceived convenience. International Journal of Information Management,36, 1350–1359.

Prendergast, G., Ko, D., & Yin, V. Y. S. (2010). Online word of mouth and consumer purchase intentions. International Journal of Advertising,29(5), 687–708.

Qin, L., Kim, Y., Hsu, J., & Tan, X. (2011). The effects of social influence on user acceptance of online social networks. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction,27(9), 885–899.

Rad, A., & Benyoucef, M. (2011). A model for understanding social commerce. Journal of Information Systems Applied Research,4(2), 63.

Salam, A., Rao, R., & Pegels, C. (1998). An investigation of consumer-perceived risk on electronic commerce transactions: The role of institutional trust and economic incentive in a social exchange framework. AMCIS 1998 Proceedings, 114.

Shiau, W.-L., & Luo, M. M. (2012). Factors affecting online group buying intention and satisfaction: A social exchange theory perspective. Computers in Human Behavior,28(6), 2431–2444.

Shin, D.-H. (2013). User experience in social commerce: In friends we trust. Behaviour and Information Technology,32(1), 52–67.

Social commerce. (2016). Facts on social commerce. Retrieved May 14, 2017 from Statista website: https://www.statista.com/topics/1280/social-commerce/.

Sparks, B. A., Perkins, H. E., & Buckley, R. (2013). Online travel reviews as persuasive communication: The effects of content type, source, and certification logos on consumer behavior. Tourism Management,39, 1–9.

Straub, D. W., Jr., & Burton-Jones, A. (2007). Veni, vidi, vici: Breaking the TAM logjam. Journal of the Association for Information Systems,8(4), 223.

Sun, Y., Liu, L., Peng, X., Dong, Y., & Barnes, S. J. (2014). Understanding Chinese users’ continuance intention toward online social networks: An integrative theoretical model. Electronic Markets,24, 57–66.

Tsai, M.-T., Cheng, N.-C., & Chen, K.-S. (2011). Understanding online group buying intention: the roles of sense of virtual community and technology acceptance factor. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence,22(10), 1091–1104.

Um, S., Chon, K., & Ro, Y. (2006). Antecedents of revisit intention. Annals of Tourism Research,33(4), 1141–1158.

Wan, Y. K. P., & Chan, S. H. J. (2013). Factors that affect the levels of tourists’ satisfaction and loyalty towards food festivals: a case study of Macau. International Journal of Tourism Research,15(3), 226–240.

Wang, C. (2014). Antecedents and consequences of perceived value in Mobile Government continuance use: An empirical research in China. Computers in Human Behavior,34, 140–147.

Wu, I.-L. (2013). The antecedents of customer satisfaction and its link to complaint intentions in online shopping: An integration of justice, technology, and trust. International Journal of Information Management,33, 166–176.

Wu, I.-L., Chuang, C.-H., & Hsu, C.-H. (2014). Information sharing and collaborative behaviors in enabling supply chain performance: A social exchange perspective. International Journal of Production Economics,148, 122–132.

Wu, Y.-L., & Li, E. Y. (2017). Marketing mix, customer value, and customer loyalty in social commerce: A stimulus-organism-response perspective. Internet Research. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-08-2016-0250.

Xiang, L., Zheng, X., Lee, M. K. O., & Zhao, D. (2016). Exploring consumers’ impulse buying behavior on social commerce platform: The role of parasocial interaction. International Journal of Information Management,36(3), 333–347.

Yen, D. C., Wu, C.-S., Cheng, F.-F., & Huang, Y.-W. (2010). Determinants of users’ intention to adopt wireless technology: An empirical study by integrating TTF with TAM. Computers in Human Behavior,26, 906–915.

Yu, C-p, Young, M.-L., & Ju, B.-C. (2015). Consumer software piracy in virtual communities: An integrative model of heroism and social exchange. Internet Research,25(2), 317–334.

Zhang, K. Z. K., & Benyoucef, M. (2016). Consumer behavior in social commerce: A literature review. Decision Support System,86, 95–108.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kwon, KJ., Mai, LW. & Peng, N. Determinants of consumers’ intentions to share knowledge and intentions to purchase on s-commerce sites: incorporating attitudes toward persuasion attempts into a social exchange model. Eurasian Bus Rev 10, 157–183 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-019-00146-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-019-00146-5