Abstract

Recently, much attention has been focused on understanding casual sex, or hooking up, among college students. The current study uses an adaptationist approach to investigate sex differences in casual sex behavior, emotional reactions, and the influence of father absence. If males and females possess different emotional mechanisms designed to evaluate the consequences of sexual behavior, we would expect sex differences in emotional reactions following that behavior. A sub-theory of life history strategy, psychosocial acceleration theory, predicts that stressful childhood environments will result in accelerated puberty and increased adult promiscuity. This study examines the impact of one childhood stressor, father absence, on casual sex, along with the previously mentioned sex differences in college students. Results indicate that (1) while there was no significant difference in the number of overall sex partners in the last 12 months, males had significantly more casual sex than did females, (2) females had significantly more negative emotional reactions to casual sex than did males, and (3) males and females who grew up in stressful childhood environments (indexed by father absence) were more likely to engage in casual sexual behavior. These results are discussed in light of sexual strategies theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent research has focused on the importance, frequency, and circumstances surrounding casual sex, or hooking up, among college students (Garcia et al. 2012; Roberson et al. 2015). Although many college students engage in longer-term sexual or romantic relationships, up to 80 % of college students report engaging in some casual sexual encounters (Garcia and Reiber 2008; Gute and Eshbaugh 2008). For many young adults, hooking up has replaced dating as a way of establishing and maintaining sexual relationships. Jonason et al. (2009) have suggested that hooking up or “booty calls” are a compromise between male and female ideal mating strategies in which males obtain greater sexual access and women obtain ongoing opportunities to evaluate potential long-term mates.

As a result of the frequency of hooking-up in the college years, many researchers have examined the positive and negative aspects of casual sex within this population. Although sex with romantic or long-term partners is often seen as providing health benefits (Levin 2007), casual sex is often perceived as providing fewer benefits and perhaps even costs in terms of mental health (Paul 2006; Townsend and Wasserman 2011). Indeed, Flack et al. (2007) have reported that 78 % of unwanted sexual experiences (including vaginal, oral, and anal intercourse) were experienced during hooking up, typically with alcohol serving to impair judgment. In addition, women were more likely (23 %) to experience unwanted sex than men (7 %).

A number of studies (Paul and Hayes 2002; Townsend and Wasserman 2011; Vrangalova 2015) have reported both positive and negative emotional reactions to casual sex as well as outcomes related to physical and mental well-being. Townsend and Wasserman (2011) reported that attitudes of sexual permissiveness were positively associated with number of sex partners for both sexes; however, even women who deliberately engaged in casual sex experienced more worry and vulnerability. For women, number of sex partners was related to increased worry/vulnerability. For men, this correlation was inverse. Paul and Hayes (2002) also reported more negative effects for women, noting that lack of contact and knowledge of a sexual partner was positively associated with anger and regret. In contrast, some studies report positive associations for both sexes between casual sexual relations and confidence, self-esteem, and sexual satisfaction (Campbell 2008; Owen and Fincham 2011). Vrangalova (2015) proposed that these mixed results suggest that there may be moderators that influence these dynamics, such as the different motivations that could lead to hooking-up.

While studies such as Olmstead et al. (2013) have examined predictors of hooking up in men, the focus has been on the influence of factors such as personality, alcohol use, permissive attitudes, and previous hooking up experience. The current study uses an adaptationist or sexual strategies perspective to examine sex differences in associations among casual sexual behavior, subsequent emotional reactions, and father absence in childhood.

Sexual Strategies and Emotions

Many problems faced by ancestral men and women were similar (finding shelter, avoiding parasitic infection, etc.). However, when it came to reproduction, men and women faced significantly different risks, costs and benefits, and opportunities. From a parental investment perspective, females are obligated to provide not only a greater initial investment in terms of eggs but also internal fertilization, gestation, and post-birth lactation, which compared to a male’s minimal required investment of sperm means that females have greater minimal obligatory parental investment in their offspring than do males (Trivers 1972). As a result, men and women evolved different strategies to solve their different reproductive problems (Buss and Schmitt 1993; Salmon and Symons 2001; Symons 1979). Female mechanisms developed to assess a male’s ability and willingness to invest in her and her offspring, the quality of his investment, and the detection of false advertising. In other words, will he provide more than the minimum investment required by insemination? In comparison, human male mechanisms include the capacity to dissociate sexual pleasure from investment and a desire for a variety of sex partners who exhibit signs of fertility (Buss and Schmitt 1993; Symons 1979). These mating strategies are not necessarily conscious; rather our emotions, our desires, and what we find attractive are what directs and motivates our mating behavior (Buss and Schmitt 1993). Emotions thus play a key role, both in terms of motivating our behavior but also in drawing attention to relevant cues and contexts, and allowing us to ruminate on poor choices or missed opportunities (Buss 1989; Roese et al. 2006; Symons 1979).

Sexual strategies theory posits that men and women possess different emotional mechanisms that are designed to motivate sexual behavior and evaluate its consequences. Thus, we would expect sex differences in both motivations and emotional reactions to casual sexual relations. Although some studies report substantial intersexual overlap in expressed motivations and reactions to casual sexual relations, some significant sex differences persist (Garcia et al. 2012; Kenrick et al. 1993; Townsend and Wasserman 2011). For example Garcia and Reiber (2008) found that compared to men, women hooked up more frequently with partners they knew and women were more likely to hope for traditional romantic relationships. Owen and Fincham (2011) also found that women were more likely to hope that hookups would lead to commitment. In the same vein, Townsend (1995) reported that even in initial hookups, women experienced more romantic thoughts than men. For women, this reported incidence of romantic thoughts did not decline with an increase in number of partners, whereas for men romantic thoughts were inversely associated with number of sex partners. In addition, research on counterfactual thinking indicates that men tend to regret actions not taken (missed sexual opportunities), whereas women regret actions taken: single sexual encounters, number of casual partners, sex with strangers or with partners who falsely promised commitment (Gute and Eshbaugh 2008; Galperin et al. 2013; Roese et al. 2006).

One result of such differences in motivation and emotional reactions is that under certain conditions, casual sex may be related to positive well-being, whereas in other circumstances, it correlates inversely with well-being. For example, in short-term mating, the following female goals can be associated with positive outcomes and reactions: Assess partners’ investment potential; test own attractiveness (mate value); gain opportunity to acquire higher investment; and acquire superior genes (Buss 1994; Buss and Schmitt 1993). In contrast, women who use short-term mating to establish relationships are often disappointed (Paul and Hayes 2002; Townsend 1995; Vrangalova 2015). In comparison, men’s emotions motivate them to engage in low-cost sex with a variety of women when the opportunities present themselves and to be less concerned about long-term intentions (Salmon and Symons 2001).

Life History Theory and Father Absence

Life history theory attempts to explain individual differences in resource allocation strategies (Brumbach et al. 2009). For example, different early environments may trigger alternative sexual strategies because individuals develop different expectations about the nature of other people, relationships (such as the durability of pair bonds), and the environment (e.g. harsh or benign, availability of parental resources). Early developmental factors can thus strongly influence which particular life history is followed (two typical strategies are discussed below). A variety of life history factors have been suggested as predictors of sexual behavior including pathogen exposure (Hill et al. 2015), deviant peer environment (Dishion et al. 2012), and inconsistent and/or unregulated parenting (Kogan et al. 2015). One additional factor that has received particular attention is father absence.

Draper and Harpending (1982) suggested that whether biological fathers were present or absent influences the reproductive strategies of their offspring. In particular, girls with absent fathers will be more likely to begin sexual activity earlier and have more sexual partners. They also suggested that there would be cognitive effects in boys, such as increased verbal and decreased math ability. Although few studies have examined effects in boys, the research on development in girls has provided some support (Ellis et al. 2003; Quinlan 2003). Belsky et al. (1991) developed a model of early environmental effects of father absence that explains two alternative paths with life history theory. The type 1 path is one of a fast life history in which marital discord, high stress, scarce resources, and insensitive parenting lead to insecure attachment, early maturation, early sexual activity, and an emphasis on short-term mating and low parental investment. This is a high quantity, low parental investment strategy. The type 2 path is a slow life history one in which there are adequate resources, positive marital relations and sensitive parenting leading to secure attachment, delayed maturation, delayed and restricted sexual activity, and high parental investment. This is a low quantity, high parental investment strategy. The type 1 path, while often seen as undesirable, would be an optimal reproductive strategy under environmental conditions associated with shortened life expectancy and generally suboptimal conditions (Nettle et al. 2011).

Psychosocial acceleration theory is the most recent articulation of this model of early environmental effects on life history strategy (Ellis et al. 2012; James et al. 2012). It suggests that stressful childhood environments can result in accelerated puberty and increased adult promiscuity for females. In fact, most relevant studies suggest that for girls, earlier puberty, earlier sexual activity, and early pregnancy are all associated with father absence (Boothroyd et al. 2013; Ellis et al. 1999; Kanazawa 2001; Maestripieri et al. 2004). Other researchers report that lack of investment or involvement from fathers can also cause these effects in boys (Bogaert 2005; Sheppard and Sear 2011). However, far fewer studies focus on effects in boys. Bogaert (2005) examined the relationship between father absence and age at puberty in a US national probability sample. For both men and women, father absence at age 14 predicted an earlier age of puberty (indexed by menarche or voice change). Sheppard and Sear’s (2011) study of British men reported that father absence before age 7 was associated with early reproduction (but also later puberty and marriage) after adjusting for other childhood adversity. These results suggest that father absence affects the sexual behavior of both males and females and that these effects are sensitive to the timing of the absence.

Current Study

In addition to attempting to replicate previous findings on casual sexual behavior and its effects, we also focus on the influence on sexual behavior of father absence in both sexes (as the majority of the literature has been focused on the impact on girls). This study began with the general hypothesis that sexually dimorphic strategies underlie the casual sexual behavior (hookups) of college students. The predictions were as follows:

-

Prediction 1: Males and females will differ in their number of casual sex partner and one-night stands.

-

Prediction 2: Females are more likely than males to worry about their partners’ intentions and to feel vulnerable following casual sexual encounters.

-

Prediction 3: Males and females who grew up in stressful childhood environments (indexed by father absence) are more likely to engage in casual sexual encounters.

Method

Participants

Participants included 344 undergraduate students (91 males, 247 females) from psychology courses at two private universities, one in the northeastern and the other in the southwestern USA. All participants were between 17 and 40 years of age (M = 19.94, SD = 2.26) and completed the survey online for course credit. Approximately 42 % of the participants self-reported their ethnicity as being Latino, 35 % Caucasian, 9 % African-American, 7 % Asian, 5 % South Asian, and 2 % Middle Eastern.

Measures

Demographics

Participants were asked to self-report their age, sex, and ethnicity. In addition, participants were asked to indicate who (and at what age) they lived with each of the following people growing up: biological mother and/or father, adoptive mother and/or father, stepmother and/or stepfather, and/or extended family (e.g., grandparents, aunt/uncle). It is important to note that, for this study, the variable of father absence was operationalized as a continuous variable. This allows us to investigate the possible effect of father absence on sexual behavior beyond the focus on only the early environment (i.e., the first 5 years of life) that characterizes much of the other research on this topic. From a theoretical perspective, it is not clear why the typical cutoff is 5 years of age. In other words, why not 6 or 7 or any pre-pubertal age if the variable of interest is age of puberty? In addition, if the variable of interest is teen or adult sexual behavior, does the father absence even need to occur pre-pubertal? Therefore, the continuous operationalization of father absence allows us to extend previous findings to include a wider age range.

Sexual Behavior

We used the three revised SOI behavior items (Penke and Asendorpf 2008) to assess incidence of casual sexual relations: (1) “With how many different partners have you had sex within the past 12 months?” (2) “With how many different partners have you had sexual intercourse on one and only one occasion?” (3) “With how many different partners have you had sexual intercourse without having an interest in a long-term committed relationship with this person?” There were nine possible response options for each of these questions ranging from “0” to “20” or more.”

Emotional Reactions

Emotional reactions to casual sex experiences were measured by three questions previously utilized in Townsend and Wasserman (2011) and Townsend et al. (2015). Participants were asked to indicate on a 9-point Likert scale (1 = strongly agree and 9 = strongly disagree) their level of agreement with the following three statements: (1) “Whenever I have sex with someone, I wonder if sex was all he/she was after,” (2) “If I have sex with someone I don’t really know, I feel vulnerable afterwards,” and (3) “If I have sex with someone I don’t really know, I would at least like to know he/she cares.” Higher scores on these questions indicate (1) less wonder (or worry) regarding the partners’ intentions, (2) fewer feelings of vulnerability resulting from the casual sex experience, and (3) less concern over whether their casual sex partner cares for them.

Procedure

Participants were sent a link to complete the survey online. Participants first responded to the demographic questions, followed by the sexual behavior and emotional reaction questions. After completion of the survey, participants were given course credit for their time.

Results

The means (and standard deviations) for age until which respondent lived with his/her biological father, number of sexual partners in the past 12 months, number of one night stands, number of casual sex partners, worry, vulnerability, and wondering if the sex partner cares for them as a function of sex appear in Table 1. Inspection of the independent sample t tests reported in the table indicates that although there was no significant sex difference in age until which respondents lived with their biological father or their number of sexual partners in the past 12 months, males did have significantly more one night stands and casual sex partners than did females. In addition, females reported significantly more worry about their partners’ intentions (i.e., wondering whether sex was all the partner was after), greater feelings of vulnerability, and greater concern whether partners cared about them after casual sex experiences.

Effect of Father Absence on Number of Sexual Partners in the Past 12 months

We conducted a hierarchical regression analysis to examine the effect of father absence on the number of sexual partners in the past 12 months. The main effects of sex of respondent and age until which the respondent lived with his/her biological father were entered in Step 1, and the interaction between those two variables was entered in Step 2.

In Step 1, the main effects of sex and age until which the respondent lived with their biological father did not significantly explain variance in the number of sexual partners in the past 12 months, F(2, 304) = 1.49, p = .23. Likewise, in Step 2, the interaction effect of sex X age until which respondent lived with his/her biological father did not significantly explain any additional variance in the number of sexual partners in the past 12 months, F(1, 303) = .19, p = .66.

Effect of Father Absence on Number of One Night Stands

We conducted a hierarchical regression analysis to examine the effect of father absence on the incidence of one-night stands. The variables were entered into the model following the same procedure described above (i.e., the main effects entered in Step 1 and the two-way interaction entered in Step 2). Results from this analysis are summarized in Table 2.

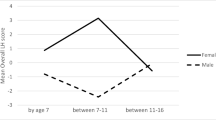

In Step 1, the main effects of sex and age until which the respondent lived with their biological father explained approximately 6 % of the variance in the number of one night stands, F(2, 301) = 9.53, p < .001. An inspection of the standardized regression coefficients (βs) indicates that sex of respondent and age until which the respondent lived with their biological father were significant unique predictors of number of one night stands. The main effect of sex indicates that males had significantly more one night stands than females. The main effect of age until which the respondent lived with his/her biological father indicates that individuals who experienced earlier father absence had significantly more one night stands.

In Step 2, the interaction effect of sex X age until which respondent lived with his/her biological father did not explain any additional variance in the number of one night stands, F(1, 300) = .003, p = .96.

Effect of Father Absence on Number of Casual Sex Partners

We conducted a separate hierarchical regression analysis to examine the effect of father absence on the number of casual sex partners. The variables were entered into the model following the same procedure described above (i.e., the main effects entered in Step 1 and the two-way interaction entered in Step 2). Results from this analysis are summarized in Table 3.

In Step 1, the main effects of sex and age until which the respondent lived with their biological father explained approximately 7 % of the variance in the number of casual sex partners, F(2, 300) = 10.83, p < .001. An inspection of the standardized regression coefficients (βs) indicates that sex of respondent and age until which the respondent lived with their biological father were significant unique predictors of number of casual sex partners. The main effect of sex indicates that males have significantly more casual sex partners than females. The main effect of age until which the respondent lived with his/her biological father indicates that individuals who experience a father absent home earlier in life have significantly more casual sex partners.

In Step 2, the two-interaction effect of sex × age until which respondent lived with his/her biological father did not explain any additional variance in the number of casual sex partners, F(1, 299) = .15, p = .70.

Discussion

The goals of the current study were to examine sex differences in the number of casual sex partners, emotional reactions to casual sex, and the relationship between father absence and casual sexual behavior. Similar to Garcia and Reiber (2008) and Townsend et al. (2015), we found no sex differences in the number of sex partners in the last 12 months. However, we did find men engaged in more one night stands and had more casual sexual partners (no time frame specified). The differences between these measures of casual sex could be due to several factors. Garcia and Reiber (2008) reported no sex difference in hooking up in the past year among college students but more men reported sex with strangers and more women reported sex with traditional romantic partners. Our sample could have varied in their answers to the casual sex questions because of variations in behavior prior to college, as we had many first year students. Furthermore, because of their different goals, males and females may have reported the same type of encounter differently: Men could perceive some encounters as completely casual and/or limited to a single instance, whereas because of their desire and intentions, women could perceive them as less casual and limited (Garcia and Reiber 2008; Paul and Hayes 2002).

Evidently, although males and females both engage in low-investment copulation and other forms of hookup behavior, their emotional reactions to such behavior show significant differences. Females exhibited more concerns than men about feeling vulnerable emotionally after hooking up as well as wondering about partners’ intentions and feelings.

From a sexual strategies perspective, such reactions would be designed to make females cautious about engaging in sexual relations, particularly with men unwilling to invest—time, affection, or resources (Buss 1989; Symons 1979). Emotional reactions can alert us to strategic interference with our mating goals (whether they are short or long-term ones) and encourage us to alter our own behavior or influence the behavior of others in ways that benefit us by reducing interference with our evolved goals (Haselton et al. 2005). For females, feeling that they have some control over investment may influence whether they subsequently view the encounter positively or negatively.

Many college students are in a life stage where they may not be in committed long-term relationships. However, this period of premarital sexual experimentation may, especially for females, conflict with evolved mechanisms that promote successful long-term mate choice once sexual maturity is reached (Armstrong and Hamilton 2009; Townsend et al. 2015). From this perspective, the greater levels of worry or vulnerability on the part of some women engaged in casual sex may be part of the emotional feedback that shapes women’s sexual behaviors and promotes the pursuit of high investment relationships as part of a long-term mating strategy.

The link between father absence (lack of paternal investment) and short life history strategy has been well-documented in girls (Ellis et al. 2012; Maestripieri et al. 2004) based on psychosocial acceleration theory, but the evidence of this in boys has been less clear (Sheppard and Sear 2011). Our results suggest that for both males and females, the earlier they were no longer living with their biological father, the more they engaged in casual sex and one night stands—behaviors associated with a developmental trajectory of early engagement in reproductive activities. Interestingly, Shukusky and Wade (2012a, b) found that men with low maternal relationship quality had attitudes supportive of peer hookups, though this was not significant for women, suggesting an impact of poor parental relationship or attachment on sexual attitudes. In our study, the earlier the father was absent, the greater the number of one night stands and casual sex partners for both males and females. Thus, father absence was a clear predictor of short-term reproductive decisions that affected both males and females, rather than a specific effect on females. In fact, it appears that this effect is also not confined to early experience (i.e., the first 5 years of childhood only).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. One concern is that the three questions related to hooking up or casual sexual behavior did not produce the same pattern of sex differences. This may be due to their wording. One specified the time frame (partners in the last 12 months), whereas the questions about one night stands and casual partners did not. Thus, the differences in these measures could reflect pre-last 12 months behavior or differences between partners perceived as casual versus more traditional romantic relationships (whether they ended up short-term or not). A majority of our students were in their first year of college. It could be useful to see whether there is a difference between the response pattern of first years and seniors or young college graduates.

In addition, as with any study in which participants self-select, there is the possibility that this sample is not representative of young college students in terms of attitudes or behaviors or that some participants might be influenced by social desirability in providing their answers despite the online survey methodology.

Future Directions

In the future, it would be useful to study casual sexual behavior in a sample including pre-college, college, and post-college individuals not only to avoid one of our limitations but also in order to examine the influence of life stage on sexual strategies and determine whether the effects of father absence persist across the life span. It may be that for many college students, the pursuit of short-term sex is a temporary strategy (Jonason et al. 2009; Townsend et al. 2015), while for some, perhaps the father absent ones, it continues over the life span. Studies with a wider age range would make this assessment possible. It would also be interesting to further investigate the effect of age at which father absence occurs on future sexual strategies. While previous research has indicated father absence from early childhood environment led to differences in sexual strategies, our findings suggest that the effect is not specific to only that early childhood environment. Further research on the effect of the age of the child when father absence occurs, how long (if at all) the father was present in the child’s life, and the level of paternal investment in the child’s life is needed. It could be that these variables (either individually and/or in combination) moderate the effect of father absence on life history strategies. For example, is the effect of father absence that occurs around puberty different from the effect of father absence at age 7 or from the effect of complete father absence?

Conclusions

A majority of both male and female college students currently engage in casual sexual relations. However, significant sex differences appear in the perception of the behavior, the motivation behind it, and emotional reactions to it. Sexual strategy and life history theories draw attention to the role of emotions and early childhood experiences in shaping sexual behavior. Our findings are consistent with our general hypothesis: Sexually dimorphic strategies appear to underlie the casual sexual behavior (hookups) of contemporary college students. Female concern about male intentions is part of an emotional system designed to guide females toward males able and willing to invest in them and their offspring. In our current environment, lengthy social adolescence (i.e., extensive premarital sexual experimentation) may exacerbate these concerns for those females who desire higher-investment relationships. In addition, our results suggest that father absence in childhood influences both male and female sexual behavior. The earlier the absence, the more frequent the casual sexual encounters. This finding has relevance for developmental research, and the long-term implications merit further study. It also suggests that father absence has predictive value in studies of both male and female sexual behavior.

References

Armstrong, E. A., & Hamilton, L. (2009). Gendered sexuality in young adulthood: double binds and flawed options. Gender & Society, 23, 589–616.

Belsky, J., Steinberg, L., & Draper, P. (1991). Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: an evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Development, 62, 647–670.

Bogaert, A. F. (2005). Age at puberty and father absence in a national probability sample. Journal of Adolescence, 28, 541–546.

Boothroyd, L. G., Craig, P. S., Crossman, R. J., & Perrett, D. I. (2013). Father absence and age at first birth in a western sample. American Journal of Human Biology, 25, 366–369.

Brumbach, B. H., Figueredo, A. J., & Ellis, B. J. (2009). Effects of harsh and unpredictable environments in adolescence on development of life history strategies. Human Nature, 20, 25–51.

Buss, D. M. (1989). Conflict between the sexes: strategic interference and the evocation of anger and upset. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 735–747.

Buss, D. M. (1994). The evolution of desire: strategies of human mating. New York: Basic Books.

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: an evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100, 204–232.

Campbell, A. (2008). The morning after the night before. Human Nature, 19, 157–173.

Dishion, T. J., Ha, T., & Véronneau, M. H. (2012). An ecological analysis of the effects of deviant peer clustering on sexual promiscuity, problem behavior, and childbearing from early adolescence to adulthood: an enhancement of the life history framework. Developmental psychology, 48, 703–717.

Draper, P., & Harpending, H. (1982). Father absence and reproductive strategy: an evolutionary perspective. Journal of Anthropological Research, 38, 255–273.

Ellis, B. J., Bates, J. E., Dodge, K. A., Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., & Pettit, G. S. (2003). Does father absence place daughters at special risk for early sexual activity and teen pregnancy? Child Development, 74, 801–821.

Ellis, B. J., McFadyen-Ketchum, S., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (1999). Quality of early family relationships and individual differences in the timing of pubertal maturation in girls: a longitudinal test of an evolutionary model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 387–401.

Ellis, B. J., Schlomer, G. L., Tilley, E. H., & Butler, E. A. (2012). Impact of fathers on risky sexual behavior in daughters: a genetically and environmentally controlled sibling study. Development and Psychopathology, 24, 317–332.

Flack, W. F., Daubman, K. A., Caron, M. L., Asadorian, J. A., D’Aureli, N. R., Gigliotti, S. N., & Stine, E. R. (2007). Risk factors and consequences of unwanted sex among university students hooking up, alcohol, and stress response. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22, 139–157.

Galperin, A., Haselton, M. G., Frederick, D. A., Poore, J., von Hippel, W., Buss, D. M., & Gonzaga, G. C. (2013). Sexual regret: evidence for evolved sex differences. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 1145–1161.

Garcia, J. R., & Reiber, C. (2008). Hook-up behavior: a biopsychosocial perspective. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 2, 192–208.

Garcia, J. R., Reiber, C., Massey, S. G., & Merriwether, A. M. (2012). Sexual hookup culture: a review. Review of General Psychology, 16, 161–176.

Gute, G., & Eshbaugh, E. M. (2008). Personality as a predictor of hooking up among college students. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 25, 26–43.

Haselton, M. G., Buss, D. M., Oubaid, V., & Angleitner, A. (2005). Sex, lies, and strategic interference: the psychology of deception between the sexes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 3–23.

Hill, S. E., Prokosch, M. L., & DelPriore, D. J. (2015). The impact of perceived disease threat on women’s desire for novel dating and sexual partners: is variety the best medicine? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 244–261.

James, J., Ellis, B. J., Schlomer, G. L., & Garber, J. (2012). Sex-specific pathways to early puberty, sexual debut, and sexual risk taking: tests of an integrated evolutionary–developmental model. Developmental Psychology, 48, 687–702.

Jonason, P. K., Li, N. P., & Cason, M. J. (2009). The “booty call”: a compromise between men’s and women’s ideal mating strategies. Journal of Sex Research, 46, 460–470.

Kanazawa, S. (2001). Why father absence might precipitate early menarche: the role of polygyny. Evolution and Human Behavior, 22, 329–334.

Kenrick, D. T., Groth, G. E., Trost, M. R., & Sadalla, E. K. (1993). Integrating evolutionary and social exchange perspectives on relationships: effects of gender, self-appraisal, and involvement level on mate selection criteria. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 951–969.

Kogan, S. M., Cho, J., Simons, L. G., Allen, K. A., Beach, S. R., Simons, R. L., & Gibbons, F. X. (2015). Pubertal timing and sexual risk behaviors among rural African American male youth: testing a model based on life history theory. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 609–618.

Levin, R. J. (2007). Sexual activity, health, and well-being: the beneficial roles of coitus and masturbation. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 22, 135–148.

Maestripieri, D., Roney, J. R., DeBias, N., Durante, K. M., & Spaepen, G. M. (2004). Father absence, menarche and interest in infants among adolescent girls. Developmental Science, 7, 560–566.

Nettle, D., Coall, D. A., & Dickins, T. E. (2011). Early-life conditions and age at first pregnancy in British women. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 278(1712), 1721–1727.

Olmstead, S. B., Pasley, K., & Fincham, F. D. (2013). Hooking up and penetrative hookups: correlates that differentiate college men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 573–583.

Owen, J., & Fincham, F. D. (2011). Young adults’ emotional reactions after hooking up encounters. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 321–330.

Paul, E. L. (2006). Beer goggles, catching feelings, and the walk of shame: the myths and realities of the hookup experience. In D. C. Kirkpatrick, S. Duck, & M. K. Foley (Eds.), Relating difficulty: the process of constructing and managing difficult relationships (pp. 141–160). Mahweh: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Paul, E. L., & Hayes, K. A. (2002). The casualties of ‘casual’ sex: a qualitative exploration of the phenomenology of college students’ hookups. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 19, 639–661.

Penke, L., & Asendorpf, J. B. (2008). Beyond global sociosexual orientations: a more differentiated look at sociosexuality and its effects on courtship and romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1113–1135.

Quinlan, R. J. (2003). Father absence, parental care, and female reproductive development. Evolution and Human Behavior, 24, 376–390.

Roberson, P. N., Olmstead, S. B., & Fincham, F. D. (2015). Hooking up during the college years: is there a pattern? Culture, Health & Sexuality, 17, 576–591.

Roese, N. J., Pennington, G. L., Coleman, J., Janicki, M., Li, N. P., & Kenrick, D. T. (2006). Sex differences in regret: all for love or some for lust? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 770–780.

Salmon, C., & Symons, D. (2001). Warrior lovers: erotic fiction, evolution and female sexuality. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sheppard, P., & Sear, R. (2011). Father absence predicts age at sexual maturity and reproductive timing in British men. Biology Letters. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0747.

Shukusky, J. A., & Wade, T. J. (2012a). Sex differences in hookup behavior: a replication and examination of parent-child relationship quality. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 6, 494–505.

Shukusky, J. A., & Wade, T. J. (2012b). Sex differences in hookup behavior: a replication and examination of parent-child relationship quality. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 6, 494–505.

Symons, D. (1979). The evolution of human sexuality. New York: Oxford University Press.

Townsend, J. M. (1995). Sex without emotional involvement: an evolutionary interpretation of sex differences. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 24, 171–204.

Townsend, J. M., & Wasserman, T. H. (2011). Sexual hookups among college students: sex differences in emotional reactions. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 1173–1181.

Townsend, J. M., Wasserman, T. H., & Rosenthal, A. (2015). Gender difference in emotional reactions and sexual coercion in casual sexual relations: an evolutionary perspective. Personality and Individual Differences, 85, 41–49.

Trivers, R. L. (1972). Parental investment and sexual selection. In B. Campbell (Ed.), Sexual selection and the descent of man: 1871-1971 (pp. 136–179). Chicago: Aldine.

Vrangalova, Z. (2015). Does casual sex harm college students’ well-being? A longitudinal investigation of the role of motivation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 945–959.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salmon, C., Townsend, J.M. & Hehman, J. Casual Sex and College Students: Sex Differences and the Impact of Father Absence. Evolutionary Psychological Science 2, 254–261 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-016-0061-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-016-0061-9