Abstract

In recent years, many Chinese listed corporations have adopted draconian takeover defenses that harm shareholders’ interests. While the courts and the Chinese Securities Regulatory Commission have failed to offer any guidance as to the validity of these defenses, the two stock exchanges in China have adopted a soft-law approach to regulating them by issuing letters of concern to listed corporations. This article makes the first attempt to empirically evaluate the effectiveness of this soft-law approach by examining the effects of takeover defenses adopted under the regulation of letters of concern with event studies. The movements of stock prices during the event period suggest that the takeover defenses adopted by listed corporations under the regulation of stock exchanges were not draconian, and that these corporations were still potential takeover targets. Thus, letters of concern issued by the two stock exchanges are effective in curbing draconian takeover defenses and protecting public investors. These findings enrich our understandings of the effects of soft law and have important implications for investor protection and the development of the capital market in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years, several hostile takeovers of listed corporations occurred in China.Footnote 1 The most famous hostile takeover battle in China so far was fought between the board of directors of Vanke, a leading Chinese listed real estate corporation, and Yao Zhenhua, the chief director of a newly established insurance corporation,Footnote 2 Qian Hai Life Insurance. Yao Zhenhua purchased above 25% of the stocks of Vanke and sought to initiate a shareholder meeting to replace the current directors, which met with fierce resistance from the listed corporation. Eventually, Vanke managed to find an outside investor, the Shenzhen Metro Group, to be its largest shareholder holding nearly 30% of its stocks, which then supported the management team and thwarted Yao Zhenhua’s attempts to take control of the board. Although the hostile takeover of Vanke failed, more hostile takeovers are likely to occur in the future since the number of listed corporations with a dispersed ownership structure is growing.Footnote 3

The threat of hostile takeovers led many listed corporations to amend their corporate charters and to adopt takeover defenses to prevent hostile acquirers from replacing directors and seizing control of the corporation. Some of these defenses are ‘draconian’—they completely preclude the occurrence of hostile takeovers and harm the interests of the target shareholders by preventing shareholders from obtaining a premium from the takeovers.Footnote 4 For example, some corporations include a provision in their corporate charters stating that hostile acquirers do not have the right to nominate directors. Other corporations impose restrictions on the number of directors that a hostile acquirer can replace. Currently, Chinese courts and the Chinese Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) have failed to provide clear guidance on the legal validity of these takeover defenses.Footnote 5

The two stock exchanges in China, however, decided to take more concrete actions. They started issuing letters of concern (‘LoCs’) (关注函) to listed corporations, asking them to consider whether these takeover defenses were in line with corporate law and whether they would harm the interests of shareholders. Since these letters are not binding regulatory measures, corporations could, in theory, ignore them with no apparent legal consequences. LoCs thus can be termed a ‘soft-law’ approach that induces listed corporations to self-regulate rather than imposing external constraints on them.Footnote 6

Whether these LoCs are effective remains an interesting and important question. Understanding the effects of LoCs may contribute to the literature on the role of stock exchanges in regulating listed corporations and protecting investors.Footnote 7 Professors Liebman and Milhaupt examine the effects of reputational sanctions imposed by stock exchanges in China, and found that they are quite effective in disciplining wrongdoings by listed corporations that violated the listing rules.Footnote 8 Unlike the reputational sanctions studied by Liebman and Milhaupt, LoCs issued by stock exchanges merely present questions to these corporations and do not have ‘shaming’ effects on them.Footnote 9 They are thus a novel type of regulatory measure and deserve more academic attention.

Moreover, studying the effects of LoCs contributes to the literature on the use of ‘soft laws’ that are not legally enforceable to address corporate governance issues.Footnote 10 Scholars have long been interested in the distinction between hard law and soft law.Footnote 11 Hard laws provide clear and certain guidance on what corporations should do, while soft laws are non-binding rules that allow corporations to choose their own rules and to explain their choices.Footnote 12 Studies have shown that soft laws are not always effective.Footnote 13 For example, a recent study suggests that the ‘comply-or-explain’ approach adopted by the European Commission has certain deficiencies.Footnote 14

Understanding the effectiveness of LoCs is also important for the development of China’s securities market, since the judicial system and the CSRC sometimes fail to effectively protect investors.Footnote 15 While corporate law is regarded by some scholars as crucial to the protection of investors and the development of the securities market,Footnote 16 Chinese corporate law is usually not enforceable against listed corporations.Footnote 17 LoCs induce self-regulation by requiring listed corporations to explain why the takeover defenses they devise are legally valid and to evaluate the impacts of these defenses on shareholders. This approach has certain benefits and costs that have not been fully analyzed.

The theme of this article is broadly connected with the academic discussion on mandatory rules in corporate law, which has attracted the interest of many legal scholars.Footnote 18 One of the major justifications for mandatory rules is the ‘opportunistic amendment hypothesis’, which suggests that corporate insiders may amend the corporate charter to increase their power and even to entrench themselves after shareholders have invested in the corporation.Footnote 19 This problem can be addressed by making certain rules mandatory, such as the constitutive rules governing the relationship between shareholders and directors.Footnote 20 Some of the takeover defenses adopted by Chinese listed corporations modify the charter provisions that govern the election of directors, which raises the suspicion of management entrenchment. Many scholars thus call for courts to treat the procedural rules as mandatory rules that cannot be amended so as to protect the interests of public shareholders.Footnote 21 This article complicates the current discussion on mandatory rules in corporate law by focusing on the soft-law regulatory approach adopted by stock exchanges, and collects empirical evidence to show that this approach may have certain advantages over mandatory rules in curbing the opportunistic amendment problem. It re-emphasizes the academic view that the opportunistic amendment problem does not fully justify mandatory rules in corporate law and argues that a soft-law approach that leaves rooms for innovation in constitutive rules plays an important role in a developing country like China.

In this article, I employ event studies to examine the effects of takeover defenses adopted under the regulation of LoCs. Starting on 3 December 2016, the CSRC and the Chinese Insurance Regulatory Commission (CIRC) made several public announcements suggesting that the regulators decided to take a stronger regulatory stance towards hostile takeovers, which would reduce the probability of takeovers in the securities market and cause the stock prices of some target corporations to drop.Footnote 22 By examining the abnormal returns of the stocks of corporations that had adopted takeover defenses when the events occurred, we can understand the effects of these takeover defenses and whether they are draconian.Footnote 23 A takeover defense is considered draconian if it precludes the occurrence of all hostile takeovers, rendering takeovers realistically unattainable.Footnote 24 Corporations with draconian takeover defenses will no longer be targets of hostile takeovers, and thus the stocks of these corporations will not be negatively affected by the event. These takeover defenses harm shareholders’ interests because they deprive shareholders of their rights to obtain premiums from hostile takeovers. If, however, takeover defenses are not draconian, there will be some probability that corporations with such defenses may still become targets of hostile acquirers. The prices of the stocks of these corporations will likely drop because of the reduction in the probability of hostile takeovers.

The results of the event studies show that the stocks of corporations that adopted takeover defenses after receiving LoCs issued by the exchanges experienced statistically significant negative abnormal returns during the event period, while the prices of stocks of many corporations with draconian takeover defenses adopted before the stock exchanges started issuing LoCs were not affected by the event. These findings suggest that the takeover defenses adopted under the regulation via LoCs were not draconian and that, as a regulatory measure, LoCs were effective in preventing listed corporations from adopting draconian takeover defenses.

This article is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, I will first review current legal theories about takeover defenses in order to illustrate the need to regulate draconian takeover defenses. I will also consider the role of stock exchanges in regulating these draconian defenses. In Sect. 3, I will conduct empirical studies to examine the effects of LoCs and to provide theoretical explanations for the results. Based on these empirical findings, I will evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of LoCs and their importance in investor protection in China in Sect. 4.

2 Regulating Draconian Takeover Defenses in China: Why and How

2.1 Why Regulate Draconian Takeover Defenses?

In recent years, listed companies with dispersed ownership have become increasingly prevalent in China. According to the WIND database, a widely used database on the stock market in China, there were more than 500 listed corporations, with their largest shareholder holding less than 20% of the corporations’ stocks in 2017.Footnote 25 About 200 corporations have a controller holding less than 20% of the shares. A group of hostile acquirers has made several attempts to takeover large listed corporations by purchasing enough of their stocks on the market.Footnote 26 These acquirers have sought to replace the board of directors following the rules set out by corporate law and the corporate charters, and then to nominate and elect their own candidates. In response to the potential hostile takeovers, listed corporations have attempted to adopt various takeover defenses. A common way to set up takeover defenses is to amend corporate charters and include in them defensive provisions that restrict the rights of hostile acquirers.Footnote 27

Hostile takeovers and takeover defenses have long been the focus of academic research. Scholars disagree on the extent to which takeover defenses should be regulated. Some scholars argue that hostile takeovers are socially beneficial—allowing hostile acquirers to assume control promotes the overall welfare of both the hostile acquirers and the target shareholders.Footnote 28 An assumption behind this argument is that the capital market can aggregate all the information available to the public and reflect the corporation’s true value.Footnote 29 Thus, as long as hostile acquirers provide a premium over the market price of stocks to shareholders, they benefit target shareholders by giving them a chance to sell their stocks at a price that the current stock market cannot offer. Hostile takeovers also benefit the hostile acquirers, since they may take advantage of the control rights of the corporation to improve its performance. Hostile acquirers may propose changes to the corporation after obtaining control, including, for example, replacing incompetent directors, which then generate high returns for hostile acquirers.

According to these scholars who argue for hostile takeovers, takeover defenses are instruments for directors to preserve their control over the corporation at the expense of shareholders.Footnote 30 These defenses will hamper the market’s role in putting the rights of corporate control to their most valuable use.Footnote 31 They are considered as obstacles to socially valuable transactions of corporate control.Footnote 32 With the help of takeover defenses, directors may set up barriers to hostile acquirers, which allow directors more time to look for other strategic investors, so-called ‘white knights’, to participate in the bid, raising the probability that a hostile takeover will fail.

Other scholars disagree and have offered several arguments in support of the efficiency of takeover defenses. A common argument is that hostile acquirers may exploit target shareholders.Footnote 33 The market price of the target corporation may not accurately reflect its intrinsic value, and shareholders may sell their stocks at low prices.Footnote 34 Another argument is that hostile takeovers may in fact harm the interests of the shareholders of the hostile acquirers. This argument goes that hostile acquirers usually pay too much in acquiring the stocks of the target corporation and cannot obtain the expected high returns after the acquisition. These hostile deals, according to this argument, are driven by the personal interests of the managers of the hostile acquirers in building up corporate empires.Footnote 35 This view has been supported by some empirical evidence.Footnote 36

Some scholars even argue that hostile takeovers not only fail to create value, but also undermine the stability of corporate management and disrupt the long-term strategies of the target corporation.Footnote 37 Since many foreign shareholders are institutional investors, their managers tend to overestimate the value of companies with higher short-term returns and to underestimate the value of long-term business strategies.Footnote 38 Thus, the mere fact that hostile acquirers are willing to offer a premium for the control of corporations does not suggest these transactions are always efficient.Footnote 39 Additionally, recent studies suggest that the stability of the board of directors is conducive to maintaining the relationship between the corporation and its suppliers, consumers, employees and creditors, and to promoting long-term cooperation.Footnote 40 If the corporation frequently replaces management because of hostile takeovers, the long-term relationship between the corporation and those groups may be undermined.Footnote 41 According to this view, hostile takeovers do not promote social welfare. Listed corporations thus should be allowed to adopt takeover defenses to safeguard the interests of shareholders and protect the value of long-term stability of the corporation.

Another argument made in support of takeover defenses is that some takeover defenses can help shareholders obtain a higher premium from hostile takeovers.Footnote 42 Consider the recent takeover battle of Vanke for example. Vanke’s management suspended all transactions of its shares, and looked for strategic investors to participate in bidding for control of the corporation. The stock price of Vanke skyrocketed when two other insurance companies, An Bang Life Insurance Co., Ltd., and Evergrand Life Insurance Co., Ltd., joined the battle, which allowed the original shareholders of Vanke to obtain a large premium in selling their stocks. This takeover battle shows that takeover defenses that delay the process of hostile takeovers could lead to more bids from strategic investors, thus benefiting target shareholders.

The above discussion suggests that academics have not yet reached a consensus over the appropriate regulation of takeover defenses. This article does not seek to address this question. It thus suffices to point out that most scholars agree that takeover defenses that become draconian and preclusive definitely harm the interests of shareholders because they prevent shareholders from obtaining a premium from hostile takeovers. Even the Delaware courts, with their reputation of favoring takeover defenses, make it clear that draconian takeover defenses that render hostile takeovers ‘realistically impossible’ are not allowed.Footnote 43 The costs of these draconian takeover defenses outweigh their benefits for target shareholders, since it does not matter how strong the target shareholders’ bargaining positions are if they cannot receive a single bid from hostile acquirers. Such takeover defenses have no other purposes than helping managers entrench themselves. It is thus important to regulate draconian takeover defenses for the purpose of investor protection. Protecting the interests of public investors, in turn, is crucial for the development of the securities market and, ultimately, for the economic development of a country.Footnote 44

2.2 How to Regulate Draconian Takeover Defenses?

While it is necessary for the law to protect shareholders’ interests by curbing draconian takeover defenses, China’s corporate law has largely failed to achieve this goal. Corporate law offers both ex ante procedural rules and ex post judicial review to protect the interests of shareholders, neither of which is effective in China. Although corporations that seek to adopt takeover defenses by amending their charter provisions need to obtain the approval of shareholders with a two-thirds majority vote in a shareholder meeting under Chinese corporate law, this procedural requirement does not guarantee that the takeover defenses adopted are in the interests of all, or even a majority of the shareholders. Chinese corporations do not need a quorum to hold a shareholder meeting. Thus, a few shareholders may control the shareholder meeting to pass amendments to corporate charters even though they only hold a small block of shares. For example, participants in the 2016 annual shareholder meeting of Zhejiang Kingland Pipeline and Technologies Co., Ltd. (002443) only held an aggregate of 12% of the stocks of the corporation.Footnote 45 In China, institutions such as mutual funds, pension funds and other investment companies do not hold a significant number of shares in listed corporations. Most stocks are owned directly by retail investors. According to the statistics provided by the Shanghai Stock Exchange, institutional investors hold only about 15% of stocks in the market.Footnote 46 Most stocks are owned by either enterprises (60%) or individuals (23%).Footnote 47 Draconian takeover defenses thus may still be approved by a shareholder meeting, which does not reflect the interests of all shareholders.

Judicial review does not provide adequate protection for public investors either. One possible legal basis for regulating draconian takeover defenses is the fiduciary duty of directors and controlling shareholders. Article 147 of the Chinese Corporate Law stipulates that directors bear a fiduciary duty towards the corporation. If a listed corporation wants to add a takeover defense provision to its corporate charter, it must go through the amendment procedure: the board of directors must resolve to propose an amendment, and then submit it to the shareholder meeting for a vote.Footnote 48 As a decision made by the board of directors, the charter amendment should not violate the principle of fiduciary duty. The adoption of takeover defenses as a decision made by the board of directors should be in line with the interests of the shareholders. Otherwise, the decision will violate the fiduciary duty of directors and may be declared void by a court.Footnote 49 Meanwhile, Article 20 of the Chinese Corporate Law stipulates that ‘shareholders shall […] exercise their rights according to law, and shall not abuse shareholders’ rights to damage the interests of the corporation or other shareholders […].’Footnote 50 Some shareholders maintain control of the board and may adopt draconian takeover defenses that ensure their grip on control of the corporation. As a result, other shareholders, especially retail investors, may not be able to receive a premium from hostile takeovers. In such cases, shareholders in control may violate Article 20 and their actions may also be declared void.Footnote 51 However, there has been no litigation against directors or controlling shareholders in listed corporations in China until very recently.Footnote 52 Thus, although listed corporations in China have adopted a variety of takeover defenses, it remains unclear whether they have violated Articles 147 and 20 of the Chinese Corporate Law, since the courts do not accept cases launched against listed corporations.Footnote 53

Courts may also impose regulations on draconian defenses by invoking mandatory rules in corporate law. For example, some corporations impose a requirement of a 270-day holding period on shareholders who seek to nominate a director. Scholars argue that such provisions violate the rules in corporate law on the election of directors, which sets no such restrictions on shareholders’ rights.Footnote 54 Professor Jeffrey Gordon regarded such rules as ‘power-allocating’, arguing that changing them may create a significant economic impact, since the corporate contract is incomplete and most decisions ‘are left to the governance structure’.Footnote 55 However, what rules in corporate law are mandatory is difficult to tell and may change over time.Footnote 56 Courts in China also have failed to make clear what rules in the Chinese Corporate Law are mandatory and not subject to change by listed corporations.

Another potential regulator of draconian takeover defenses is the CSRC. Article 80 of the Measures for the Administration of the Takeover of Listed Companies provides that the CSRC has the power to order listed corporations to change their charter provisions that violate the law.Footnote 57 In fact, the CSRC intervened once in takeover defenses adopted by listed corporations, in 1998. In that case, a corporation called Dagang Oil Field attempted a hostile takeover of Shanghai Ace Co. Ltd. (600652). Shanghai Ace Co. Ltd., adopted a takeover defense in its corporate charter limiting the rights of hostile acquirers to nominate directors. The CSRC declared that the charter provision was not consistent with the law, requiring Shanghai Ace Co. Ltd., to amend its charter. However, today a large number of listed companies still have similar provisions in their corporate charters, the validity of which remains questionable. So far, the CSRC has not taken any action against these takeover defenses.

While the courts and the CSRC have largely failed to impose regulations on draconian takeover defenses, the two stock exchanges have recently decided to take action.Footnote 58 While they lack formal power to investigate and to sanction listed corporations,Footnote 59 they started to issue informal LoCs to listed corporations that adopted takeover defenses in 2016. In these LoCs, they require listed corporations to answer a set of questions, including whether the takeover defenses comply with corporate law, whether they adversely affect the interests of shareholders, what measures have been taken to protect the interests of shareholders, and whether they treat all shareholders fairly.Footnote 60 The stock exchanges did not take sides on whether these defenses are allowed by the Chinese Corporate Law, but simply required corporations to consider the issue. Issuing LoCs to listed corporations can be regarded as a soft-law approach since LoCs are not legally binding. In theory, listed corporations could just ignore these letters. They could reply to the stock exchanges affirming that they believe the relevant takeover defenses are valid and proceed to adopt them.

As a soft-law measure, LoCs may exert pressure on listed corporations and induce self-regulation by listed corporations. This regulatory measure may engage regulated corporations that possess expertise and valuable information in developing regulatory measures, and thus promotes regulatory capacity.Footnote 61 Self-regulation also reduces monitoring costs and the costs of enacting and amending regulatory rules and standards.Footnote 62 However, self-regulation may be abused because the regulated parties are not publicly accountable and thus may choose to lower the regulatory standards.Footnote 63 Specifically, LoCs provide listed corporations with significant discretion in devising defensive provisions. They may thus design draconian takeover defenses that are seemingly beneficial to shareholders. Managers and corporate controllers may possess insider information as to how to design defensive provisions that can thwart hostile acquirers while not drawing too much attention from the regulators and the stock exchanges.

To sum up, while the effects of takeover defenses are still debatable, certain draconian defenses will harm the interests of public shareholders and need to be regulated. While courts and the CSRC have failed to take actions against these draconian takeover defenses, LoCs play a significant role in regulating them in China. Whether LoCs are effective in regulating draconian takeover defenses remains an interesting and important question. The following sections will employ empirical evidence in China to examine the effects of LoCs.

3 Empirical Studies of the Effects of Takeover Defenses under the Regulation of Stock Exchanges

3.1 Takeover Defenses Prior to 2016

While very few hostile takeovers occurred in China prior to 2015, many listed corporations have long adopted takeover defenses. Using Google as a search engine, I searched for ‘hostile takeover’, ‘no nomination rights’, and ‘corporate charter’ and found about 30 corporations that included provisions in their corporate charters addressing hostile takeovers prior to 2016. Some of these corporations set insurmountable hurdles to hostile acquirers, damaged shareholder interests and violated the Chinese Corporate Law. For example, Article 83 of the corporate charter of Boya Bio-pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd., in October 2012, required a potential investor in the corporation to ‘request the Board of Directors to convene a temporary shareholder meeting to consider whether to welcome the acquisition.’Footnote 64 If the acquirer failed to comply with the above provisions or if a shareholder resolution were passed to disapprove the acquisition, the acquirer would be treated as hostile. In such cases, the acquirer does not have the rights to nominate or vote for directors, pursuant to the corporate charter provisions. These provisions enable managers to entrench themselves and harm the interests of shareholders. Without the right to elect a director, hostile acquirers are likely to abandon their takeover attempts, which undermines the shareholders’ chances of receiving a premium for their stocks. These takeover defenses are thus draconian and should be regulated.

3.2 Takeover Defenses Adopted under the Regulation of Stock Exchanges

3.2.1 Corporations That Changed Their Defensive Measures After Receiving LoCs

Things started to change, however, in 2016, when the stock exchanges began using LoCs as a regulatory measure. Since January 2016, the Shanghai Stock Exchange and Shenzhen Stock Exchange have expressed concerns about takeover defenses adopted by listed companies by issuing LoCs. I searched the websites of the two stock exchanges and found 18 LoCs issued between 1 January 2016 and 31 November 2016, against corporations who attempted to adopt takeover defenses. Among these corporations, three completely gave up the attempt to adopt takeover defenses after receiving LoCs.Footnote 65 The remaining 15 adopted takeover defenses despite receiving LoCs; three of these corporations amended their proposed charter provisions after receiving LoCs.

Takeover defenses adopted in 2016 do not directly deprive hostile acquirers of their right to nominate directors. This may be because the regulators’ warning and the exchanges’ concern have created some pressure on listed companies, preventing them from taking excessive defensive measures.

The first LoC was issued to Longping High-Tech Co., Ltd (Longping High-Tech). Longping High-Tech went public in 2000. However, in 2006, the corporation proposed an amendment and adopted defensive provisions. Article 38 of the proposed charter states:

Any shareholder who holds or jointly holds with another person by agreement or other arrangement 10% of the corporation’s issued shares shall disclose to the corporation, within three days after the acquisition of the shares, information on the holding of the shares of the corporation and the plan to increase its position, and request the Board of Directors to convene a shareholder meeting to consider whether to approve the acquisition […] Investors who fail to comply with this requirement of disclosure, or whose disclosure is not timely, incomplete, untrue, or who fails to obtain the approval of the shareholder meeting, would be regarded as hostile acquirer and does not have the rights to nominate corporation directors and the rights to propose the convening of a temporary shareholder meeting.Footnote 66

Pursuant to this provision, the board of directors of Longping High-Tech can always treat an investor as a hostile acquirer and prevent it from nominating and electing directors. Besides this restriction on hostile acquirers, Longping High-Tech also requires shareholders to hold more than 8% of the shares for 180 consecutive days before they can nominate a director.

In January 2016, Longping High-Tech proposed several amendments to its corporate charter. First, it proposed that the corporation not replace more than one-third of the total number of directors within 36 consecutive months without cause, whereas its previous charter stipulated that the corporation not replace more than one-third of the total number of directors within a year. Second, in the event of a hostile takeover, a candidate nominated by the acquirer shall have at least five years of experience in similar businesses in order to safeguard the overall interests of the corporation and its shareholders and the stability of the corporation’s business decisions. Besides these restrictions, Longping High-Tech proposed that proposals made by a hostile acquirer to enter into major transactions with the corporation need to be approved by a two-thirds majority at a shareholder meeting.Footnote 67

While these new defensive measures limit hostile takeovers to some extent, they pale in significance compared with the provisions that Longping High-Tech adopted earlier. However, the resolution regarding the charter amendment drew the attention of the Shenzhen Stock Exchange. It issued a LoC stating that the amended corporate charter would contain several defensive measures and required the corporation to explain whether the new charter would be consistent with corporate law.Footnote 68 As stated above, no courts had ruled on whether these takeover defenses violated corporate law at that time—nor did the Shenzhen Stock Exchange imply that they did. The stock exchange merely expressed its concerns in its letters. As a result, Longping High-Tech revised its proposed takeover defenses and deleted Article 38 that deprived hostile acquirers of their right to nominate directors. Instead, it adopted a provision limiting the number of directors that can be replaced within 36 consecutive months.Footnote 69

Two other corporations amended their proposals after receiving LoCs. The Chinese Huashen Group attempted to add a provision to its charter depriving the hostile acquirer of its rights to nominate a director. Following a LoC from the Shenzhen Stock Exchange, the board of directors of the corporation abandoned the takeover defenses it originally proposed and only adopted a charter provision that authorized directors to take defensive measures when a hostile takeover would occur. Shandong Jintai Group Co., Ltd. proposed, on 12 August 2016, to include in its charter several provisions restricting the rights of hostile acquirers, including for example, a provision limiting the number of directors that can be replaced to two-thirds of the total number of directors when their terms end.Footnote 70 After receiving the LoC, this corporation abandoned the original provisions and required a shareholder to hold 3% of the stocks of the corporation for 270 days consecutively before the shareholder can call a shareholder meeting and nominate a director.Footnote 71

3.2.2 Typical Takeover Defenses Adopted Under the Regulation of LoCs

Defensive charter provisions adopted after January 2016 have clearly become more similar to each other, perhaps because listed companies refer to each other’s corporate charters when they devise their takeover defenses. It is thus possible to give a brief summary of the major types of defensive provisions adopted by these corporations.

In 2016, corporations that adopted takeover defenses usually included in their corporate charters a definition of hostile takeovers. Most corporate charters define hostile takeover as acquisitions made without informing and obtaining the approval of the target corporation. Once an investor is identified as a hostile acquirer, all the restrictions on hostile acquirers apply.

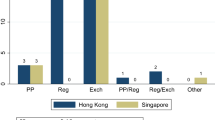

Table 1 presents the major takeover defenses of the 15 corporations that received LoCs between 1 January and 1 December 2016.Footnote 72 Most corporations restrict the rights of hostile acquirers to remove, nominate or elect directors. Five of the 15 corporations stipulate that no more than one-third of the members of the board can be replaced once their terms expire after a hostile takeover has occurred, and the hostile acquirer can only replace one-fourth of the members every year afterwards. Another corporation stipulates that half of the directors shall remain in their position, while the hostile acquirer can only replace one-fourth every year afterwards.Footnote 73 Two corporations set a 270-day holding period requirement for shareholders to nominate a director; another corporation sets a 90-day requirement. One corporation limits the number of directors that can be replaced before their terms expire to one-fourth per year.Footnote 74 Two other corporations only allow shareholders to replace one-third of the directors every 36 months.Footnote 75 The remaining three corporations do not limit the voting and nominating rights of hostile acquirers. Besides the restrictions on their rights to nominate and elect directors, several corporate charters also impose limitations on the qualifications of directors and require them to have at least 5 years’ working experience in similar businesses. Some companies also adopted the defensive provision stipulating that in the event of a hostile takeover, at least one director must be elected by the employees of the corporation.

These 15 corporations also adopted other takeover defenses. Many corporations adopted ‘golden-parachute’ provisions, which require corporations to compensate directors if they are removed without cause. The amount of compensation is generally five times or ten times the amount of salary of the director in the previous year. Moreover, some corporations require a two-thirds majority vote to approve a shareholder resolution when a hostile acquirer submits a shareholder proposal for a major asset sale or acquisition transaction. Finally, many corporations authorize the board of directors to take any anti-takeover measures it deems necessary. In the event of a hostile takeover, the board does not need to obtain a shareholder resolution to take an outright takeover measure.

The effects of these takeover defenses remain unclear if we simply analyze them qualitatively. For corporations with a dispersed ownership structure, the key to seizing control of them is to replace and elect directors. Defensive provisions mainly restrict the rights of hostile acquirers to remove and appoint directors. It remains unclear, however, whether they were draconian or preclusive. For example, five of these corporations adopted charter provisions that prevent hostile acquirers from replacing more than one-third of the directors when their terms expire if a hostile takeover occurs. After that, only one-fourth of the directors can be replaced every year. At first glance, this arrangement does not completely preclude the occurrence of a hostile takeover but simply delays the process of a takeover. For example, if a listed corporation has nine directors, a hostile acquirer can replace three directors at the end of the board’s term. In the following year, the hostile acquirer can replace two more directors. If hostile acquirers start acquiring stocks prior to the expiration of the board’s term, they can control a majority of the board in less than 2 years. Moreover, if a hostile acquirer succeeds in obtaining the directors’ consent to resign, it can gain control more quickly. However, these provisions have made it more difficult and costly to acquire target companies. Although the takeover defenses do not seem preclusive, the market conditions render it realistically unattainable to acquire control of the corporation. In fact, one of the major worries about the enforced self-regulation approach is that ‘companies would write their rules in ways that would assist them to evade the spirit of the law’.Footnote 76 The effects of self-regulation thus remain an important empirical question.Footnote 77

3.3 Event Studies

I now turn to a quantitative analysis of defensive measures adopted under the regulation of stock exchanges in order to evaluate whether LoCs are effective in regulating draconian takeover defenses. Empirical studies on the effects of takeover defenses usually take two approaches—cross-sectional and time-series. Some scholars examine the cross-sectional correlation between takeover defenses such as a staggered board and the value of the corporation, usually measured by Tobin’s Q.Footnote 78 The problem with this approach is the issue of endogeneity or ‘reversed causation’—corporations that perform worse may be more inclined to adopt takeover defenses.Footnote 79 A second approach is to examine the change in the value of the corporations before and after their adoption of a staggered board.Footnote 80 The problem with this approach, however, is that the adoption of takeover defenses may have other confounding effects on the stock prices of these corporations. For example, shareholders would expect corporations that adopt a staggered board to be more likely to become the targets of hostile takeovers, which may lead to a rise in the returns of the stocks.Footnote 81 To address the endogeneity problems, I use the speeches by regulators as events, which are exogenous shocks to the market, to test the effects of takeover defenses adopted under the regulation of the stock exchanges in China.

A series of events in December 2016 can be employed to examine the effects of takeover defenses in China. The chairman of the CSRC, Shiyu Liu, gave a speech on 3 December 2016, criticizing hostile takeovers.Footnote 82 The vice chairman of the CIRC also expressed concerns about hostile takeovers on 4 December 2016.Footnote 83 On 7 December 2016, the CIRC announced a regulatory investigation of Qianhai Life Insurance Co., Ltd. and Evergrand Life Insurance Co., Ltd, two insurance companies that engaged actively in hostile takeover activities, which also showed a tightening of control over hostile takeovers.Footnote 84 On 9 December 2016, the CIRC issued a notice barring Evergrand Life Insurance Co., Ltd from trading its stocks.Footnote 85 The chairman of the CIRC gave another speech on the evening of 13 December 2016 suggesting that they would take a tougher stance against insurance companies acting as hostile acquirers.Footnote 86 I define the event day (t) as the date on which the market first started trading after the first speech by the CSRC, which is 5 December 2016.

These statements and regulatory actions by the CSRC and CIRC show their negative attitude towards hostile takeovers, which reduced the number of hostile takeovers in the market and the probability that the target corporation would be acquired. If takeover defenses had already rendered hostile takeovers realistically unattainable, the listed corporations that had adopted these defensive measures were no longer the targets of hostile takeovers. In that case, the corporations’ share prices would not be affected by these statements and actions. If, by contrast, the defensive provisions that these corporations adopted did not completely preclude the occurrence of hostile takeovers, these companies still had some probability of being acquired and shareholders could still obtain a premium in selling their stocks. In that case, stock prices would likely fall significantly during the event period because the regulators’ stance reduced the chances that shareholders would obtain the premium. The abrupt change in regulatory attitude was an exogenous shock to the market, creating a ‘natural experiment’ that can be used for empirical analysis.

To study the effects of takeover defenses adopted after the stock exchanges started regulating listed corporations via LoCs, I examined four different baskets of stocks.Footnote 87 Basket 1 includes the stocks of 14 corporations that adopted defensive measures after receiving LoCs between January 2016 and November 2016.Footnote 88 Basket 2 includes the stocks of 17 corporations that I found on ‘www.cninfo.com.cn’, a CSRC-designated website where all listed corporations disclose their information, with Google using the key words ‘hostile takeover’, ‘no nomination rights’ and ‘corporate charters’. These 17 corporations adopted similar takeover defenses preventing hostile acquirers from nominating or electing directors prior to 2016, at a time when the stock exchanges did not regulate via LoCs. Pursuant to these provisions, hostile acquirers cannot nominate directors and thus would not seek to acquire these corporations. Basket 3 includes the stocks of 148 listed corporations with a controlling shareholder holding 50.01–55% of their stocks.Footnote 89 Basket 4 includes the stocks of 331 listed corporations with a controlling shareholder holding 50.01–70% of their stocks.Footnote 90 Corporations in Basket 3 and 4 were not subject to the threats of hostile takeovers and would not have been affected by the events in theory. The summary statistics of these corporations are presented in Table 2.Footnote 91

Three portfolios for a hypothetical investor are constructed: in Portfolio A, the investor takes a long position by spending $1 to purchase the stocks in Basket 1 and a short position by selling $1 of the stocks of corporations in Basket 2; in Portfolio B, the investor takes a long position in Basket 1 and a short position in Basket 3Footnote 92; in Portfolio C, the investor takes a long position in Basket 1 and a short position in Basket 4. I calculated the market-adjusted returns that the investor would have earned by investing in these three portfolios.

The market-adjusted return of the three portfolios is calculated by subtracting from the actual return of the portfolio the expected return of the portfolio, which is calculated as:

Rit denotes the actual return of Portfolio i on day t, calculated by subtracting from the average return of the equally weighted stocks in the basket that the investor longs the average return of the equally weighted stocks in the basket that the investor shorts. Meanwhile, \( \left( {\hat{\alpha }_{i} + \hat{\beta }_{i} \times R_{mt} } \right) \) is the expected return of Portfolio i on day t. \( R_{mt} \) is the average return of equally weighted stocks listed on the two stock exchanges in China on day t. \( \hat{\alpha }_{i} \) and \( \hat{\beta }_{i} \) are estimated using the following market model and data in the estimation window [t-200,t-5]:

The estimation window of this model dates from −150 to −5. The null hypothesis to be tested is that the Portfolios A, B and C have market-adjusted returns that are larger or equal to zero during the event period. Since stocks in Basket 2, 3 or 4 would not, in theory, be affected by the events, rejecting the hypothesis would suggest stocks in Basket 1 were statistically significantly influenced by the speeches of regulators in a negative way, meaning the 14 corporations that adopted takeover defenses in 2016 were still targets for hostile takeovers and that the takeover measures did not completely rule out the possibility of hostile takeovers.

To conduct a statistical test to see whether the market-adjusted returns of Portfolios A, B and C are statistically below zero, I use the standard deviation of the market-adjusted returns of the two portfolios in the estimation window to estimate the standard deviation during the event window.Footnote 93 The event windows are [t, t + 4] and [t, t + 10]. I choose wide event windows because there were similar events on 7 December 2016 (t + 2), 9 December 2016 (t + 4) and 14 December 2016 (t + 7) that had similar effects on these corporations.

The results are shown in Results (Basket 1, 2 and Portfolio A) (Table 3). The impacts of the events on the stocks in Basket 1 depend on the event window. During the five-day event window, stocks in Basket 1 experienced a significant negative abnormal return.Footnote 94 Although this effect is not statistically significant during the eleven-day window, the average abnormal return of stocks in Basket 1 is still negative. Stocks in Basket 2, however, were not significantly affected by the events. The abnormal returns of stocks in Basket 2 during the two event windows are both positive. The market-adjusted returns of Portfolio A are negative and statistically significant during the two event windows. This suggests that the events had negative impacts on stocks in Basket 1 but no such effects on stocks in Basket 2.Footnote 95

Additionally, as Table 4 shows, the events resulted in positive abnormal returns of stocks in Basket 3 during the five-day event window. The market-adjusted returns of Portfolio B are negative during the two event windows. The negative return of Portfolio B is statistically significant during the 5-day event window and marginally significant during the eleven-day event window. It suggests that the events adversely influenced stocks in Basket 1 but not those in Basket 3.Footnote 96 Similarly, the events had a stronger negative impact on stocks in Basket 1 than on those in Basket 4 during the 5-day event window (see Appendix Fig. 4).

While the sample size of Basket 1 corporations remains quite limited, I use the ‘SQ test’ developed recently, to be used in event studies with small samples to replace the t-statistics and test the hypothesis.Footnote 97 The abnormal return of Basket 1 on the event day, 0.66%, is below the tenth most negative value during the estimation window, as is shown in Fig. 1. In other words, there are only 9 days during the estimation window on which Basket 1 had a more negative value than the return on the event day, suggesting that the abnormal return of Basket 1 on the event day is not likely to be random. Stocks in Basket 1 were at least marginally significantly influenced by the event.

These findings suggest that takeover defenses adopted under the regulation via LoCs are not draconian because the stocks of corporations that adopted these defenses were still adversely influenced by the events, suggesting that these corporations were still potential targets for hostile takeovers. A potential counter-argument to this conclusion is that stock investors in China may not have closely examined these corporate charter provisions because they either lacked expertise or did not pay any attention to such details. However, the fact that the market-adjusted returns of Portfolio A were negatively affected by the events also suggests that stock investors have noticed the differences between corporations with different takeover defenses. Moreover, takeover defenses drew wide attention from the public in 2016. Market participants were likely to closely study these provisions and to invest in corporations that they believed to be potential targets for hostile acquirers.

An alternative interpretation of these findings is that regulatory actions taken by the CIRC caused insurance companies to liquidate their stocks, which led to a drop in stock prices. To examine the validity of this interpretation, I examined the 2016 annual report of the listed corporations in Basket 1 and found that in four corporations, Xiamen Savings Environmental Co., Ltd., Zhejiang Kingland Pipeline and Technologies Co., Ltd., Xiamen Academy of Building Research Group Co., Ltd., and Yuan Longping High-tech Agriculture Co., Ltd., insurance companies had above 1% of shares. However, since none of the insurance companies that invested in these corporations were investigated or sanctioned by the CIRC, this interpretation is likely incorrect.

3.4 Theoretical Explanations for the Empirical Results

The empirical findings above suggest that takeover defenses adopted under the regulation via LoCs are not draconian and are different from those adopted before 2016, suggesting that the soft-law approach is effective in curbing draconian takeover defenses. A couple of explanations could be offered for these results. While LoCs are not legally binding or enforceable, they may draw the attention of the public. The reaction of listed corporations to LoCs may thus have a signaling effect—the stock prices of listed corporations may plummet if corporations do not react properly and continue to adopt draconian takeover defenses.Footnote 98 Insiders of these listed corporations may suffer monetary losses since they usually hold some of the corporate stocks.

Meanwhile, to answer the questions posed in LoCs about the legal validity of these takeover defenses, listed corporations frequently engaged law firms to issue legal opinions stating that these defenses were legally valid. Lawyers may not be willing to issue an opinion stating that certain draconian takeover defenses are valid, for fear that the opinion will later be contradicted by the court or the regulators. The reluctance of law firms to issue such opinions may also influence the decisions of listed corporations.

Finally, listed corporations may expect the stock exchanges or the CSRC to take more aggressive regulatory measures if these corporations simply ignore the LoCs and continue to adopt draconian defensive measures. Once their defensive provisions are declared invalid for violating corporate law, they may face more severe consequences, such as legal sanctions from the CSRC or reputational sanctions from the stock exchanges. Research has shown that managers of listed corporations in China may suffer reputational damages due to the reputational sanctions by stock exchanges, which may affect their future career.Footnote 99 The potential possibility that regulators would adopt escalated regulatory measures may render non-coercive measures sufficient to deter listed corporations from wrongdoings.Footnote 100

4 Implications

4.1 Policy Implications: Evaluation of LoCs as a Regulatory Measure

4.1.1 Strengths of LoCs

The above empirical evidence suggests LoCs are effective in regulating draconian takeover defenses and deserve more attention. In the academic literature, scholars have identified two major approaches to investor protection: the formal legal approach and the informal self-regulation approach.Footnote 101 The Law and Finance literature developed by La Porta et al. suggests that legal protection of investors promotes the development of the financial market.Footnote 102 Other scholars, however, emphasize that in developing countries such as China, the informal approach may play a much more significant role.Footnote 103 This article offers further empirical evidence that the informal approach is effective. Moreover, using a self-regulation approach by issuing LoCs to regulate listed corporations offers several advantages compared to the formal legal approach—speed, flexibility, and facilitation of experiments.

Stock exchanges can react much faster compared to courts and may thus offer a speedy response to newly emerged but urgent legal issues. Since takeover defenses have only been adopted recently and have not yet resulted in many litigations, it takes a long time for courts to review these defenses and to provide guidance as to their validity. Even if public investors can initiate a legal action, it takes courts a long time to deliver an opinion. Once a court finds a takeover defense to be invalid, listed corporations can revise it slightly, causing significant uncertainty to the validity of these charter provisions. A hostile acquirer will then need to initiate litigation every time an innovative takeover defense is adopted, creating significant litigation costs for the hostile acquirer. Additionally, scholars have not reached a consensus either as to what rules in corporate law should be regarded as mandatory.Footnote 104 LoCs thus may be a better way to regulate draconian defensive measures devised by corporations than litigations. This argument is also consistent with the academic view that ‘public exposure may be the single most effective tool for combating wrongdoing in China today’.Footnote 105

LoCs also enjoy the advantage of flexibility. Stock exchanges can issue LoCs to address emerging issues regarding which the law has not provided clear guidance.Footnote 106 Courts and the CSRC may not want to determine early on whether a particular innovative takeover defense is legally valid or not, for fear that the rigidity of the regulation and rules may prevent charter provisions that are socially beneficial from being adopted. Scholars inside and outside China still debate fiercely about what types of takeover defenses should be allowedFootnote 107; a consensus about how best to regulate these takeover defenses takes time to reach.

As a soft-law approach, LoCs do not risk imposing too many constraints on listed corporations and thus facilitate experiments with innovative takeover defenses that may be socially beneficial. Scholars have long recognized that Chinese law ‘contains space for innovation’ and that ‘experiments and devolutions of lawmaking’ are common in China.Footnote 108 Stock exchanges may collaborate with listed corporations in developing appropriate laws on takeover defenses, which may generate knowledge and consensus on the relevant legal issues. LoCs can regulate draconian takeover defenses that harm the interests of public investors, while leaving enough room for innovative takeover defenses that may enhance the business stability of listed corporations.Footnote 109 This novel and important regulatory measure thus facilitates the learning process that is crucial to the development of law on a subtle and complicated legal issue.Footnote 110

4.1.2 Weaknesses of LoCs

While this article suggests that LoCs are effective in curbing draconian takeover defenses, they also have certain weaknesses.Footnote 111 One problem associated with regulation by stock exchanges is the problem of ‘capture’—certain powerful corporations may influence the decisions by regulators so that the regulatory decisions benefit them at the expense of public investors.Footnote 112 Like other regulators, stock exchanges may be captured by listed corporations and choose not to issue LoCs to protect the reputation of the corporations. However, given that the contents of the corporate charters of listed corporations are public information, all amendments of these charters will inevitably draw public attention. If some corporations adopted draconian takeover defenses but did not receive LoCs, it would certainly be noticed.Footnote 113 Thus, this problem is likely to be less severe compared to other regulatory measures taken against listed corporations.

In addition, although the empirical evidence in this article suggests that takeover defenses adopted under the regulation of LoCs were not draconian, they may still reduce the value of the corporation and be socially inefficient.Footnote 114 As discussed above, the optimal level of takeover defenses is subject to debate. These defenses reduce the probability of shareholders receiving a premium, while increasing the size of the premium.Footnote 115 Whether they benefit shareholders depends on which effect is stronger.

Moreover, even if takeover defenses promote shareholder value, they may still be socially undesirable. Professors Gilson and Schwartz have shown that the level of takeover defenses that is beneficial for target shareholders may not be socially beneficial,Footnote 116 since the costs imposed on hostile acquirers may be higher than the benefits created for target shareholders.

Thus, the empirical evidence in this article does not imply that takeover defenses adopted under the regulation via LoCs are socially optimal. LoCs may still be insufficient in regulating takeover defenses and maximizing social welfare, since they put too much discretion in the hands of corporate managers.Footnote 117 Nor does this article imply that China should not develop its formal legal regimes to further tighten its control over draconian takeover defenses. It merely emphasizes the value of LoCs as an effective soft-law approach and calls for expanding the use of LoCs in other, similar corporate law issues. This form of regulation also deserves more academic interest as a useful regulatory tool in curbing the wrongdoings of listed corporations that might be important in other developing countries with similar legal institutions and facing similar problems.

4.2 Theoretical Implications

The effectiveness of LoCs also has significant theoretical implications. Scholars have proposed several hypotheses that justify mandatory rules in corporate law, the most important one among them being the opportunistic amendment hypothesis.Footnote 118 This hypothesis, however, has not been empirically tested. China offers a precious opportunity for testing it, because Chinese corporate law is still in its incipient stage of development and courts have not provided clear rules on what rules in corporate law are mandatory. As a result, many listed corporations have chosen to deviate from corporate law, allowing us to observe how corporations behave when there are no clear mandatory rules in corporate law. Moreover, since the hypotheses that justify mandatory rules in corporate law are based on the simple assumptions of rational investors and managers, they should be universal and should explain the phenomena in China if they are indeed correct.

Empirical evidence in China lends supports to the opportunistic amendment hypothesis. Without mandatory rules, corporations choose to deviate from the standard rules in corporate law, which allows managers to increase their power and entrench themselves after investors have purchased stocks of the corporation and to thus harm the interests of investors. However, it does not necessarily follow that mandatory corporate law enforced by courts should be employed to regulate draconian takeover defenses. The soft-law approach adopted by the stock exchanges has not imposed rigid constraints on corporations. Rather, it allows corporations to self-regulate and to consider whether the takeover defenses they adopted are in line with the interests of the shareholders. While this article does not dispute that mandatory rules may address the opportunistic amendment problem, it intends to emphasize that this problem could be addressed by different regulatory methods and by different institutions.Footnote 119

5 Conclusion

Draconian takeover defenses harm the interests of public investors because they prevent them from obtaining premiums in selling their shares to hostile acquirers. While the law on takeover defenses is highly developed in the United States and Europe, China has only recently started to face these legal issues. As a result, corporate law in China has failed to provide sufficient protection to public investors against draconian takeover defenses. In this article, I test the effects of LoCs, using event studies. I find that this type of regulatory measure is effective in curbing draconian takeover defenses. As a soft-law approach, LoCs enjoy the advantages of being flexible and are thus especially important in responding to emerging legal issues to which the law has been slow to react. This study contributes to the study of investor protection in developing countries and innovative regulatory measures that may overcome the problem of capture and enhance regulatory capacity. It suggests that the opportunistic amendment problem identified by some scholars does not justify mandatory rules in corporate law. A soft-law approach has certain advantages in curbing wrongdoings of corporations, at least in the institutional environment in China.

Notes

The hostile takeover battle that attracted the most attention was fought between the boards of directors of Vanke and Baoneng. See Baowan Dazhan Liangdipai Shuangfang Kaiqi Zhengmian Jiaofeng (宝万大战亮底牌 双方开启正面交锋) [The Battle between Vanke and Baoneng Has Started], Zhongguo Zhengquanbao (中国证券报) [China Securities Daily], 20 December 2015.

These investors usually take on financial leverages by controlling insurance companies and borrowing from institutional investors or individuals with high net worth. Yao Zhenhua was a CEO of Qianhai Life Insurance. He also financed the takeover activities by initiating asset-management plans provided by mutual fund management companies or their subsidiaries.

Most hostile acquirers seek only to acquire enough shares to nominate directors in order to control the management of the corporations. They do not propose mergers with the target corporations because most listed corporations have ‘shell value’ since the status of listed corporations is difficult to obtain due to the tight regulation of the initial public offering. Thus, most hostile acquirers seek only to obtain control by controlling the board of directors.

The Delaware courts have developed sophisticated legal doctrines to review the decisions of the board of directors. Corporations usually cannot adopt ‘draconian’ takeover defenses that harm shareholders’ interests. Unitrin, Inc. v. American General Corp., 651 A.2d 1361 (Del. 1995). Hostile takeovers have long attracted academic attention. For decades, scholars have fiercely debated the efficiency of takeover defenses. See Easterbrook and Fischel (1981); Bebchuk et al. (2002); Bebchuk et al. (2009); Coffee (1984); Strine (2006); Lipton (1979); Jarrell et al. (1988); Greenwood and Schor (2009); Cremers and Sepe (2016); Romano (2010), p 489.

The CSRC only warned that listed corporations should not adopt takeover defenses that may harm the interests of their shareholders. Li Tianzhen (李天真), Zhengjianhui: Bude Liyong Fanshougou Tiaokuan Xianzhi Gudong Quanli (证监会:不得利用反收购条款限制股东权利) [CSRC: Listed Corporations Should Not Use Takeover Defenses to Restrict the Rights of Shareholders], Zhongguo Zhengquanbao (中国证券报) [China Securities Daily], 27 August 2016.

See Hopt (2011), p 11; Trubek (2006), p 149 (‘There is also a development of informal processes to resolve grievances and disputes, including negotiation and multistepped procedures. This can be called “soft law”.’ ‘“Hard law” can be characterized as command and control, court-based dispute resolution, uniform rules, punitive sanctions, and court challenges for noncompliance.’).

Aguilera et al. (2013), pp 23-45.

De Jong et al. (2005).

RiskMatrics (2009), p 168 (‘Although the comply-or-explain approach is considered an appropriate and efficient regulatory tool by a large majority of market actors and regulators, there is also a wide consensus that the mechanism does not function perfectly. Moreover, the role of deficiencies in corporate governance practices was highlighted as one of the causes of the late 2000 financial crisis’).

Liebman and Milhaupt (2008), p 967.

La Porta et al. (1997), pp 1149–1150.

Clarke and Howson (2012), p 277.

Gordon (1989), p 1573.

Gordon (1989), p 1573.

See e.g., Zhang (2009), p 122.

Liu Shiyu: Fandui Yemanren Qiangdaoshi Shougou Tiaozhan Xingfa Jiang Kaiqi Laoyu Damen (刘士余:反对野蛮人强盗式收购 挑战刑法将开启牢狱大门) [Liu Shiyu: Objecting to Hostile Takeovers by Gangsters, Those Who Challenge the Criminal Law Shall Pay for it], Fenghuang Caijing Xun (凤凰财经讯) [Phoenix Financial News], 3 December 2016, http://finance.ifeng.com/a/20161203/15052057_0.shtml (last visited 31 December 2017); Baojianhui Chen Wenhui: Baoxian Gongsi Raokai Jianguan Xujia Zengzi shi Fanzui (保监会陈文辉:保险公司绕开监管虚假增资是犯罪) [Chen Wenhui of the CIRC: Insurance Companies That Fail to Comply with the Regulatory Rules on Capital Regulation Are Committing Crimes], Diyi Caijing (第一财经) [China Business News], 4 December 2016, http://www.yicai.com/news/5174552.html (last visited 31 December 2017).

The stock market in China is frequently influenced by announcements made by public officials. See Xu and Li (2001).

Unitrin, Inc. v. American General Corp., 651 A.2d 1361 (Del. 1995).

In 2017, the total number of corporations listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Exchanges was about 3400.

The hostile takeover battle that attracted the most attention was fought between the directors of Vanke and Baoneng. See Baowan Dazhan Liangdipai Shuangfang Kaiqi Zhengmian Jiaofeng (宝万大战亮底牌 双方开启正面交锋) [The Battle Between Vanke and Baoneng Has Started], Zhongguo Zhengquanbao (中国证券报) [China Securities Daily], 20 December 2015.

In China, poison pills are not available because the issuance of stocks needs to be approved by the shareholder meeting and cannot be authorized by the board of directors alone. For a detailed discussion of these defenses, see infra Sect. 3.

Bebchuk et al. (2002), p 891.

Fama (1970), p 383.

See Jensen and Meckling (1976).

Bebchuk et al. (2002), p 891.

Bebchuk et al. (2002), p 891.

Coffee (1984), p 1169.

Romano (1992), p 148 (‘The motivation for an acquisition is the maximization of the manager’s utility rather than of the shareholders’ wealth, or more simply put, self-aggrandizement.’).

Jarrell et al. (1988), p 53 (‘The 159 cases from the 1980 s show statistically insignificant losses to bidders.’).

Cremers and Sepe (2016), p 80.

Cremers and Sepe (2016), p 80.

Coffee (1984), p 1175.

Unocal Corp. v. Mesa Petroleum Co., 493 A.2d 946, 956 (Del. 1985); Unitrin, Inc. v. American General Corp., 651 A.2d 1361 (Del. 1995).

See generally La Porta et al. (2008), p 326.

The 2016 Annual Shareholder Meeting of Zhejiang Kingland Pipeline and Technologies Co., Ltd., http://www.cninfo.com.cn/cninfo-new/disclosure/szse_sme/bulletin_detail/true/1203537247?announceTime=2017-05-19 (accessed 29 December 2017).

Shanghai Stock Exchange Statistical Yearbook 625 (2017).

Shanghai Stock Exchange Statistical Yearbook 625 (2017).

Shareholders who collectively hold above 3% may also propose an amendment pursuant to the corporate charters. Gongsi Fa (公司法) [Company Law] (promulgated by the Standing Committee of the National Congress, 28 December 2013, effective 1 March 2014), Art. 103.

Gongsi Fa (公司法) [Company Law] (promulgated by the Standing Committee of the National Congress, 28 December 2013, effective 1 March 2014), Art. 22.

Gongsi Fa (公司法) [Company Law] (promulgated by the Standing Committee of the National Congress, 28 December 2013, effective 1 March 2014), Art. 20.

Gongsi Fa (公司法) [Company Law] (promulgated by the Standing Committee of the National Congress, 28 December 2013, effective 1 March 2014), Art. 22.

Professors Clarke and Howson have pointed out that this is probably because courts do not accept cases involving large numbers of plaintiffs. See Clarke and Howson (2012), p 277. Recently however, China set up a China Securities Investor Services Center (中证中小投资者服务中心有限责任公司), a public-oriented corporation controlled by the CSRC to represent the interests of minority shareholders in listed corporations. It has decided to launch lawsuits against several listed corporations. It is possible that courts may play a larger role in regulating draconian takeover defenses in the future.

It thus remains unclear whether the defensive measures comply with the Chinese Corporate Law.

Zhang (2009), p 125.

See Gordon (1989), pp 1591–1592 (‘Many mandatory rules of corporate law allocate power throughout the governance structure, affecting, in particular, the balance of power between directors and shareholders. The managerial role of the board, shareholder voting rights in the election of directors, and shareholder removal rights are classic examples.’). See also Eisenberg (1989), pp 1463–1466.

Coffee (1989), p 1627 (‘A review of those cases dealing with true contractual departures […] shows both that courts have permitted some deviations and rejected others and that the trend in judicial decisions has been toward greater tolerance.’).

Shangshi Gongsi Shougou Guanli Banfa (2014 nian xiuding) (上市公司收购管理办法(2014修订)) [Measures for the Administration of the Takeover of Listed Companies (2014 Revision)], promulgated on 13 December 2014 and in effect on 1 September 2006. Available at http://pkulaw.cn/fulltext_form.aspx?Db=chl&Gid=21e31a6f80542175bdfb&keyword=%E4%B8%8A%E5%B8%82%E5%85%AC%E5%8F%B8%E6%94%B6%E8%B4%AD%E7%AE%A1%E7%90%86%E5%8A%9E%E6%B3%95&EncodingName=&Search_Mode=accurate&Search_IsTitle=0 (accessed 9 January 2019).

China’s stock exchanges are controlled by the government and act as regulators. The CSRC has the power to appoint or remove the general manager of the exchanges. One common regulatory measure of stock exchanges is to criticize listed corporations for violation of regulatory rules and for harming investors. Professors Liebman and Milhaupt have studied the effects of criticisms from stock exchanges on listed corporations and found that they play a significant role in protecting investors. Liebman and Milhaupt (2008).

Liebman and Milhaupt (2008), p 945.

See e.g., Taijia Gufen Guanyu dui Shenzhen Zhengquan Jiaoyisuo Guanzhuhan Huifu de Gonggao (泰嘉股份关于对深圳证券交易所关注函回复的公告) [Taijia’s Public Notice of the Response to the Letters of Concern Issued by the Shenzhen Stock Exchange], available at http://www.cninfo.com.cn/cninfo-new/disclosure/szse_sme/bulletin_detail/true/1203186671?announceTime=2017-03-23 (accessed 9 January 2019).

Ogus (1995), p 98 (‘self-regulatory agencies can normally command a greater degree of expertise and technical knowledge.’).

Ogus (1995), p 98.

The Corporate Charter of Boya Bio-pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd., http://www.cninfo.com.cn/cninfo-new/disclosure/szse_gem/bulletin_detail/true/1200731472?announceTime=2015-03-24 (last visited 15 December 2017).

These three corporations are Sichuan Yahua Industrial Group Co., Ltd (000790), Sichuan Jinlu Group Co., Ltd. (000510) and Inner Mongolia Yili Industrial Group Co., Ltd. (600887). The reason they abandoned the attempt remains unclear. Perhaps they believed they were not in danger of being acquired after all and therefore did not go through with the plan.

The Corporate Charter of Longping High-Tech Co., Ltd., http://www.cninfo.com.cn/cninfo-new/disclosure/szse_main/bulletin_detail/true/1200462885?announceTime=2014-12-13 (last visited 15 December 2017).

The Corporate Charter of Longping High-Tech Co., Ltd., http://www.cninfo.com.cn/cninfo-new/disclosure/szse_main/bulletin_detail/true/1200462885?announceTime=2014-12-13 (last visited 15 December 2017), Art. 77.

For example, in addressing Longping High-Tech’s amendment of Art. 38, the Shenzhen Exchange states in its letter: ‘please check whether the amendment complies with Article 4, Article 101 and Article 102’. The Shenzhen Stock Exchange seems to have ignored the fact that many of these takeover defenses were in place prior to the proposed amendment. Guanyu Dui Yuanlongping Nongye Gaokeji Gufen Youxian Gongsi de Guanzhuhan (关于对袁隆平农业高科技股份有限公司的关注函) [Letters of Concern Issued to Long Pint High-Tech], http://www.szse.cn/UpFiles/fxklwxhj/CDD00099837191.PDF (last visited 15 December 2017).

Yuanlongping Nongye Gaokeji Gufen Youxian Gongsi Di Liu Jie Dongshihui Di Ershiwu ci Linshi Huiyi Jueyi Gonggao (袁隆平农业高科技股份有限公司第六届董事会第二十五次(临时)会议决议公告) [The 25th (Interim) Board Resolution of the Sixth Board of Longping High-Tech], http://www.cninfo.com.cn/cninfo-new/disclosure/szse_main/bulletin_detail/true/1201920581?announceTime=2016-01-16 (last visited 15 December 2017).

Board Resolution of Shandong Jintai Group Co., Ltd., http://www.cninfo.com.cn/cninfo-new/disclosure/sse/bulletin_detail/true/1202560241?announceTime=2016-08-12 (last visited 15 December 2017).

Corporate Charter of Shandong Jintai Group Co., Ltd., available at http://www.cninfo.com.cn/cninfo-new/disclosure/sse/bulletin_detail/true/1202656094?announceTime=2016-08-31 (last visited 15 December 2017).

I choose this period because in the following event studies, I am considering the impacts on these corporations of the events that occurred on 3 December 2016.

The Corporate Charter of China Baoan Group Co., Ltd., http://www.cninfo.com.cn/cninfo-new/disclosure/szse_main/bulletin_detail/true/1202438448?announceTime=2016-06-30 (last visited 15 December 2017).

The Corporate Charter of Shanghai Liangxin Electrical Co., ltd., http://www.cninfo.com.cn/cninfo-new/disclosure/szse_sme/bulletin_detail/true/1202841147?announceTime=2016-11-24 (last visited 15 December 2017).

Yuanlongping Nongye Gaokeji Gufen Youxian Gongsi Di Liu Jie Dongshihui Di Ershiwu ci Linshi Huiyi Jueyi Gonggao (袁隆平农业高科技股份有限公司第六届董事会第二十五次(临时)会议决议公告) [The 25th (Interim) Board Resolution of the Sixth Board of Longping High-Tech], http://www.cninfo.com.cn/cninfo-new/disclosure/szse_main/bulletin_detail/true/1201920581?announceTime=2016-01-16 (last visited 15 December 2017).

Ayres and Braithwaite (1992), p 124.

Ayres and Braithwaite (1992), p 125. (‘We strongly suspect that simple, particularistic rules over which business had considerable control would not be more susceptible to evasion than complex rules over which business had less control because the whole inherited wisdom from the study of corporate crime is that it is complexity that makes conviction so often impossible. Ultimately, however, this question can only be answered empirically.’).

Bebchuk et al. (2009).

Cremers and Sepe (2016), p 90.

Cremers and Sepe (2016), p 104.

Liu Shiyu: Fandui Yemanren Qiangdaoshi Shougou Tiaozhan Xingfa Jiang Kaiqi Laoyu Damen (刘士余:反对野蛮人强盗式收购 挑战刑法将开启牢狱大门) [Liu Shiyu: Objecting to Hostile Takeovers by Gangsters, Those Who Challenge the Criminal Law Shall Pay for it], Phoenix Financial News (凤凰财经讯), 3 December 2016, http://finance.ifeng.com/a/20161203/15052057_0.shtml (last visited 31 December 2017).

Baojianhui Chen Wenhui: Baoxian Gongsi Raokai Jianguan Xujia Zengzi shi Fanzui (保监会陈文辉:保险公司绕开监管虚假增资是犯罪) [Chen Wenhui of the CIRC: Insurance Companies That Fail to Comply with the Regulatory Rules on Capital Regulation Are Committing Crimes], China Business News (第一财经), 4 December 2016, http://www.yicai.com/news/5174552.html (last visited 31 December 2017).

Baojianhui Diaocha Ruzhu Qianhai Renshou Baoxianye Jianguan Quyan (保监会调查组入驻前海人寿 保险业监管趋严) [CIRC Investigation Group Enter Qianhai Life Insurance, Regulation on the Insurance Industry Tightens], China Times (华夏时报), 7 December 2016.

Guanyu Zanting Hengda Renshou Baoxian Youxiangongsi Weituo Gupiao Touzi Yewu de Tongzhi (关于暂停恒大人寿保险有限公司委托股票投资业务的通知) [Notice on Suspending the Trading of Stocks by Evergrand Life Co., Ltd.], http://www.circ.gov.cn/web/site0/tab6527/info4052820.htm (last visited 31 December 2017.).

Baojianhui Zhuxi: Jueburang Baoxianjigou Cheng Yemanren (保监会主席:绝不让保险机构成’野蛮人’) [Do not Let Insurance Companies Become Barbarians at the Gate], Beijing News (新京报), 14 December 2016.

All data used in this article comes from the SinoFin-CCER database.

Initially I have 15 corporations. However, the stocks of one of these corporations (Xinjiang Yilu Wanyuan Industrial Investment Holding Co., Ltd.) were not traded when the events occurred. After I exclude this corporation, the final basket includes equally weighted stocks of 14 corporations.

The information about the ownership structure of these 148 corporations is based on their 2016 annual report. There were 183 corporations in total with a controlling shareholder holding 50.01–55% of the stocks listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange and Shenzhen Stock Exchange. I excluded the corporations that were not traded for up to 150 days in a year prior to the event, and those that were not traded on the event day.

The information about the ownership structure of these 331 corporations is based on their 2016 annual report. There were 410 corporations in total with a controlling shareholder holding 50.01–70% of the stocks listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange and Shenzhen Stock Exchange. Again, I excluded the corporations that were not traded for up to 150 days in a year prior to the event, and those that were not traded on the event day. There are finally 331 corporations left in the basket. I did not include corporations with a controlling shareholder holding above 70% of the corporate stocks because these stocks are relatively illiquid and their prices are likely affected by other factors.

Information about the shareholders of these corporations comes from the 2016 annual report of these corporations, collected through the Sinofin-CCER Database.

Using a portfolio approach may alleviate the omitted variable bias of the study, since for an omitted variable to create bias in this study, it has to be correlated with the portfolio and not just with stocks in one of these baskets.

Brown and Warner (1980), p 251.

Negative abnormal returns of Basket 1 were marginally significant using a ten-day event window.

Figure 2 in the Appendix presents the cumulative abnormal return of Portfolio A during the event period.

Figure 3 in the Appendix presents the cumulative abnormal return of Portfolio B during the event period.

Gelbach, Helland and Klick (2013).