Abstract

Purpose

Vitamin D is a relatively inexpensive drug yet an important hormone in terms of calcium and bone homeostasis. Treatment with vitamin D is associated with reduced fracture risk particularly in an elderly population. Therefore, we assessed the budgetary impact of routine prescription of 800 IU daily colecalciferol on hip fracture among older adults in the United Kingdom.

Methods

Using meta-analysis findings for treatment effect and UK-estimates of incidence, we performed a health economic evaluation of treating the UK population aged 65 and over with 800 IU of vitamin D daily, assessing the impact upon hip fracture costs using incremental attributable costs and excess mortality for a range of age- gender-based treatment strategies.

Results

Using only a 1-year horizon, considering only reduction in hip fracture, prescribing colecalciferol 800 IU daily to all adults aged 65 and over, could reduce the number of incident hip fractures from 65,400 to 45,700, saving almost 1,700 associated deaths, whilst saving the UK taxpayer £22 million.

Conclusions

As the UK government seeks to reduce public expenditure in all sectors, investment in prescribed prophylactic colecalciferol 800 IU therapy for adults aged 65 and over is likely to yield cost savings through reduction hip fracture alone in the first year.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since the beneficial effects of cod liver oil were noted in the original work of Mellanby [1] in treating Rickets, Vitamin D has emerged as an important steroid hormone in calcium, muscle and bone homeostasis. Its role in the prevention of both rickets and osteomalacia is well established yet more recently it has been implicated in many extra-skeletal effects including muscle, immune and neurological function [2].

The vast majority of vitamin D in the body is manufactured through photosynthesis rather than obtained through diet. Due to a number of factors including geographical latitude, successful campaigns to avoid sun exposure and an aging population, vitamin D deficiency is common with increasing incidence found in the elderly, obese and amongst certain ethic groups [3, 4]. In adulthood, the spectrum of deficiency may extend from few symptoms to osteomalacia with reduced bone strength, pseudo-fractures and proximal muscle weakness. Also, hypovitaminosis D has been shown to be strongly associated with mortality from all causes, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and respiratory diseases [5].

Oral vitamin D is a safe and effective treatment for vitamin D deficiency, relieving symptoms and improving calcium and bone metabolism [6], muscle strength [7, 8], neurological function [9, 10] and risk of falls [11, 12]. A recent meta-analysis of vitamin D interventions reported a significant 30 % reduction in the risk of hip fractures as well as a 14 % reduction in non-vertebral fractures among subjects receiving doses above 792 IU per day [13].

In consequence of the benefits, as well as the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency within the population, the Chief Medical Officers of the UK produced a letter advocating replacement therapy and, in particular, recommended the daily use of 400 IU of vitamin D by all adults over the age of 65 [14]. Controversy persists regarding the adequacy of vitamin D dosing with meta-analyses revealing that a dose of 400 IU per day is ineffective with regard to treating deficiency as well as the prevention of falls and fractures [13, 15]. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the health and economic impact of treating all UK subjects over the age of 65 with vitamin D therapy with respect solely to the reduction in hip fractures.

Methods

We conservatively modelled a scenario in which all UK adults over 65 years of age would be prescribed vitamin D at a daily dose of 800 IU. Treatment effects would be mediated solely from a reduction in hip fracture risk. The payer perspective was that of UK health and social care agencies. The model uses a 1-year horizon of treatment.

Modelled population

The study utilised the structure of the resident population of the UK from the 2011 Census [16]. An usual resident of the UK is anyone who, on census day, was in the UK and had stayed or intended to stay in the UK for a period of 12 months or more, or had a permanent UK address and was outside the UK and intended to be outside the UK for less than 12 months.

Treatment

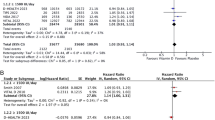

In their recent letter to health professionals [14], the Chief Medical Officers of the UK did not specify how adults aged 65 and over should access daily supplements of vitamin D. Bischoff-Ferrari et al. [13] reported pooled participant-level data from 11 double-blind, randomised, controlled trials of oral vitamin D supplementation (daily, weekly, or every four months), with or without calcium, as compared with placebo or calcium alone in persons 65 years of age or older. Only in the highest quartile of actual intake (median, 800 IU daily) was reduction in the risk of hip fracture observed (hazard ratio 0.70; 95 % CI 0.58–0.86). This observation was consistent across subgroups defined by age group, residence status, baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D level, and additional calcium intake and is consistent with observations relating to falls [15]. The primary analysis adjusted for baseline characteristics.

In the UK, two licensed oral colecalciferol 800 IU/unit dose preparations are available (Desunin® and Fultium-D3®). Both are prescription-only medicines (PoM) and have an annual ingredient cost of £43.80 [17].

Hip fracture

Incidence of hip fracture was taken from a study of anonymised longitudinal UK general practice records (The Health Improvement Network; THIN) [18]. Incidence above the age of 85 was conservatively estimated from another contemporary THIN-based study of hip fractures using data for older persons without Alzheimers disease [19].

The average cost of hip fracture was estimated from a Health Promotion England report [20] published in 2000. Costs borne by health (excluding private healthcare costs) and social care agencies included: hospital admissions; ambulance costs; and social care, general practitioner and outpatient costs for survivors (Table 1). The total cost [£726 million (M)] divided by the number of hip fractures modelled (47,471) indexed to 2012 prices’ [21] results in an average current cost of each hip fracture of £24,303 in Year 1. This compared closely to recent Canadian data [22] showing the mean attributable cost in the first year after hip fracture to be Can$37,575 (or £23,867 at the time of writing [23]).

Associated mortality

Age-specific data for 1-year mortality following hip fracture in the UK were unavailable and therefore estimated from Swedish data [24]. Applying the ratio of 1-year post-fracture: background mortality to age- gender-specific UK death rates [25], mortality associated with hip fracture was estimated.

Results

Based on the current incidence rates (Fig. 1), our model estimates there to be around 65,400 incident hip fractures per annum in UK residents over the age of 65, more than three-quarters of which (77 %) will occur in women. The overall annual ‘first year’ cost to health and social care services of managing incident hip fractures is therefore estimated to be £1.59 billion (BN) (Table 2).

The annual cost of vitamin D supplementation at a dose of 800 IU per day plus hip fracture management would be £1.57BN, a net saving in expenditure of £22 M. Analysis of the pattern of net marginal cost differs markedly for different gender–age groups as shown in Fig. 2. As a consequence of the increasing incidence of hip fracture with increasing age, Colecalciferol treatment (800 IU per day) among all women over 75 years of age, and men over the age of 85 would produce cost savings in their respective age–gender groups, from −£8.2 M per annum (women aged 75–79) to −£131.3 M (women aged 85 and over) (Fig. 2). Alternative treatment targeting strategies based only on age group (Fig. 3) and confined to the prevention of hip fracture reveal that treatment of all adults over 80 years with colecalciferol 800 IU could result in a net annual saving to health and social care budgets of approximately £192.5 M.

Based on the data revealing a 30 % reduction in risk of hip fractures associated with a dose of Vitamin D at or above 800 IU daily [13], the number of incident hip fractures within the UK could be reduced to approximately 45,800. Our model estimates that such a strategy could prevent almost 1,700 associated deaths per annum (Fig. 3).

Discussion

In light of recent meta-analytic data showing that doses of vitamin D less than 800 IU daily are unlikely to elicit a reduction in hip fracture and other non-vertebral fracture [13], the value of the UK Chief Medical Officers’ recommendation for universal daily dosing at 400 IU [14] is questionable.

This study of the budget impact of population prophylactic treatment within high-risk groups of elderly with prescribed vitamin D at a dose of 800 IU per day would result in costs savings to the NHS and social care if applied to all men and women over 65 years, after only considering benefits from a likely reduction in the frequency of hip fractures. Furthermore, 1,700 deaths annually attributable to hip fracture would also be avoided. More substantial savings of £124 million may be expected through targeted treatment of all adults aged 70 and over through prevention of hip fractures consistent with the observation that amongst all fractures, fracture of the hip imposes the greatest morbidity and mortality to an elderly population [26].

The model is necessarily conservative. In line with MHRA advice [27], only vitamin D treatment with ethical prescribed formulations has been considered to ensure consistent cost and quality [28, 29].

The annual cost of hip fracture is currently estimated to be greater than £2 billion [30] (compared to a modelled estimate of £1.6BN) and further substantial cost savings could reasonably be expected. A 1-year time horizon for this model is a limitation, but was conservatively chosen. Therefore, on-going long-term residential care costs for the 50 % of year-1 survivors of hip fracture are not accounted for. Given that, in the first year, social care costs account for 67 % of the total expenditure on hip fracture [20], and that fewer than 1 % of adults in residential or nursing care return to independent living [31], the true long-term cost of hip fracture would be much higher. Although labour force participation of the at-risk population is low, productive losses due to family and carer burden arising from hip fracture in a relative could be in excess of £100 M at 2012 prices [20]. Inclusion of non-vertebral non-hip fractures within the current model would also have added to the cost savings [32], although the treatment effect expected from vitamin D supplementation is less marked for this outcome [13].

The use of data on hip fractures-associated mortality from the Swedish population potentially increases the heterogeneity of the data used in the analysis. We were unable to find similar UK data with age-band specific post-fracture mortality. Nevertheless, our method of applying an age- gender-specific ratio to background UK death rates’ models first year post-fracture mortality (16.9 %) comparably to the most contemporary estimates [19, 33, 34] which show that approximately one-fifth of those experiencing hip fracture will die within the first year. The conclusion that vitamin D could prevent premature death is supported by other meta-analyses suggesting that a small reduction in mortality can be expected following vitamin D treatment [35, 36].

Our study also lacks evaluation of potential comorbidities, a further limitation. In this regard, we conservatively used non-Alzheimers fracture incidence in the very elderly and also used aggregated background mortality which includes death arising from fracture, which would make our estimates of attributable mortality conservative.

Application of findings from a meta-analysis of specifically designed studies applied to the general population could represent a possible bias and a limitation of the study. However, subgroup analyses conducted by Bischoff-Ferrari et al. found consistent treatment effects across age groups and also between community residence and institutional settings (OR 0.68 vs. 0.70, respectively). Therefore, we feel justified that the results of the adjusted primary analysis are reasonably applied to the general population. The meta-analysis has been criticised [37] though the counter arguments offered seem reasonable. Whilst fracture risk reduction is not in itself under debate, the requirement for calcium in addition to vitamin D to achieve this reduction is. However, the authors of the meta-analysis argue cogently that calcium is not required to achieve the fracture risk reduction. Also, supplemental calcium may be unnecessary, as the majority of elderly subjects have an adequate dietary calcium intake, whereas vitamin D intake is inadequate [38], a likely contributor to the epidemic of vitamin D deficiency. Similarly, the value of calcium supplementation has been questioned with regard to increased cardiovascular risk [39] and nephrolithiasis [36].

In conclusion, this study is the first to examine the health economic impact of hip fracture reduction through treating an aging population with vitamin D. Unlike the recommendation of using a dose of 400 IU daily in all subjects 65 and over, for which studies would suggest little, if any benefit, treating all adults 65 years and over with vitamin D 800 IU daily would also be expected to reduce morbidity and mortality in an elderly population. From the health economic perspective, greatest savings are seen following the treatment of subjects 70 years and over with similar reductions in mortality. This abbreviated analysis suggests the need for further studies to specifically evaluate the health economic impact of vitamin D supplementation, especially at doses currently recommended for vitamin D deficiency prevention.

References

Mellanby E (1976) Nutrition Classics. The Lancet 1:407-12, 1919. An experimental investigation of rickets. Edward Mellanby. Nutr Rev 34:338–340

Norman AW (2008) From vitamin D to hormone D: fundamentals of the vitamin D endocrine system essential for good health. Am J Clin Nutr 88:491S–499S

Darling AL, Hart KH, Macdonald HM et al (2013) Vitamin D deficiency in UK South Asian Women of childbearing age: a comparative longitudinal investigation with UK Caucasian women. Osteoporos Int 24:477–488

Hyppönen E, Power C (2007) Hypovitaminosis D in British adults at age 45 year: nationwide cohort study of dietary and lifestyle predictors. Am J Clin Nutr 85:860–868

Schöttker B, Haug U, Schomburg L et al (2013) Strong associations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations with all-cause, cardiovascular, cancer, and respiratory disease mortality in a large cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 25:782–793

Pearce SH, Cheetham TD (2010) Diagnosis and management of vitamin D deficiency. BMJ 340:b5664

Lee HJ, Gong HS, Song CH et al (2013) Evaluation of vitamin D level and grip strength recovery in women with a distal radius fracture. J Hand Surg Am 38:519–525

Diamond T, Wong YK, Golombick T (2013) Effect of oral cholecalciferol 2,000 versus 5,000 IU on serum vitamin D, PTH, bone and muscle strength in patients with vitamin D deficiency. Osteoporos Int 24:1101–1105

Dhesi JK, Jackson SHD, Bearne LM et al (2004) Vitamin D supplementation improves neuromuscular function in older people who fall. Age Ageing 33:589–595

Muir SW, Montero-Odasso M (2011) Effect of vitamin D supplementation on muscle strength, gait and balance in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 59:2291–2300

Murad MH, Elamin KB, Abu Elnour NO et al (2011) Clinical review: The effect of vitamin D on falls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96:2997–3006

Cameron ID, Gillespie LD, Robertson MC et al (2012) Interventions for preventing falls in older people in care facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12:CD005465

Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Orav EJ et al (2012) A pooled analysis of vitamin D dose requirements for fracture prevention. N Engl J Med 367:40–49

Davies SC, Jewell T, McBride M, et al. VITAMIN D–ADVICE ON SUPPLEMENTS FOR AT RISK GROUPS. London: Department of Health 2012. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/vitamin-d-advice-on-supplements-for-at-risk-groups

Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Staehelin HB et al (2009) Fall prevention with supplemental and active forms of vitamin D: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 339:b3692

Office for National Statistics (2011) Mortality figures for United Kingdom. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/hub/population/deaths/mortality-rates. (Accessed 14 Apr 2013)

NHSBSA Prescription Services. Electronic Drug Tariff. http://www.ppa.org.uk/ppa/edt_intro.htm. (Accessed 14 Apr 2014)

Collins GS, Mallett S, Altman DG (2011) Predicting risk of osteoporotic and hip fracture in the United Kingdom: prospective independent and external validation of Q fracture scores. BMJ 342:d3651

Baker NL, Cook MN, Arrighi HM et al (2011) Hip fracture risk and subsequent mortality among Alzheimer’s disease patients in the United Kingdom, 1988–2007. Age Ageing 40:49–54

Parrott S. The Economic Cost of Hip Fracture in the UK. York: 00. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://www.berr.gov.uk/files/file21463.pdf

HM Treasury (2012) 2012 GDP deflators.http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/data_gdp_index.htm. (Accessed 29 Mar 2013)

Nikitovic M, Wodchis WP, Krahn MD et al (2013) Direct health-care costs attributed to hip fractures among seniors: a matched cohort study. Osteoporos Int 24:659–669

XE.com (2013) XE currency conversion. http://www.xe.com/ucc/convert/?Amount=37575&From=CAD&To=GBP. (Accessed 14 Apr 2013)

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O et al (2003) The components of excess mortality after hip fracture. Bone 32:468–473

Office for National Statistics (2012) Death Registrations Summary Tables–England and Wales, 2011 (Final). http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/vsob1/death-reg-sum-tables/2011-final-/index.html. (Accessed 14 May 2013)

Woolf AD, Akesson K (2003) Preventing fractures in elderly people. BMJ 327:89–95

MHRA. Off-label or unlicensed use of medicines: prescribers’ responsibilities. http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Safetyinformation/DrugSafetyUpdate/CON087990. (Accessed 14 Apr 2013)

Leblanc ES, Perrin N, Johnson JD et al (2013) Over-the-counter and compounded vitamin D: is potency what we expect? JAMA Intern Med 173:585–586

Garg S, Sabri D, Kanji J et al (2013) Evaluation of vitamin D medicines and dietary supplements and the physicochemical analysis of selected formulations. J Nutr Health Aging 17:158–161

British Orthopaedic Association (2007) The care of patients with fragility fracture. http://www.bgs.org.uk/pdf_cms/pubs/Blue%20Book%20on%20fragility%20fracture%20care.pdf. Accessed 14 Apr 2014

Bebbington A, Darton R, Netten A. Elderly people admitted to residential and nursing homes: 42 months on 2000. http://www.pssru.ac.uk/pdf/p051.pdf

Gutiérrez L, Roskell N, Castellsague J et al (2012) Clinical burden and incremental cost of fractures in postmenopausal women in the United Kingdom. Bone 51:324–331

Holt G, Smith R, Duncan K et al (2008) Epidemiology and outcome after hip fracture in the under 65 s-evidence from the Scottish hip fracture audit. Injury 39:1175–1181

Gunasekera N, Boulton C, Morris C et al (2010) Hip fracture audit: the Nottingham experience. Osteoporos Int 21:S647–S653

Autier P, Gandini S (2007) Vitamin D supplementation and total mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 167:1730–1737

Bjelakovic G, Gluud LL, Nikolova D et al (2011) Vitamin D supplementation for prevention of mortality in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7:CD007470

Grey A, Bolland M, Reid I (2012) Vitamin D dose requirements for fracture prevention. N Engl J Med 367:1367–1370

Gibson S (2001) Dietary sugars and micronutrient dilution in normal adults aged 65 years and over. Public Health Nutr 4:1235–1244

Bolland MJ, Grey A, Avenell A et al (2011) Calcium supplements with or without vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular events: reanalysis of the Women’s Health Initiative limited access dataset and meta-analysis. BMJ 342:d2040

British Medical Association, Royal Pharmaceutical Society (2013) British National Formulary. 65th edn. BMJ Publishing & Pharmaceutical Press 2013. http://www.bnf.org

Conflict of interest

Dr Poole has previously consulted for Internis Pharmaceuticals (manufacturer of Fultium-D3), Astellas and Norgine. Dr Davies is a medical advisor to Internis Pharmaceuticals and has undertaken consultancy work for Meda (Manufacturer of Desunin) and Prostrakan (manufacturers of Adcal-D3). Dr Smith has nothing to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Poole, C.D., Smith, J.C. & Davies, J.S. The short-term impact of vitamin D-based hip fracture prevention in older adults in the United Kingdom. J Endocrinol Invest 37, 811–817 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-014-0109-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-014-0109-2