Abstract

Although some children with feeding disorders may have the necessary skills to feed themselves, they may lack motivation to self-feed solids and liquids. Rivas, Piazza, Roane, Volkert, Stewart, Kadey, and Groff (Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47, 1–14, 2014) and Vaz, Volkert, and Piazza (Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 915–920, 2011) successfully increased self-feeding for children who lacked motivation to self-feed by manipulating either the quantity or the quantity and quality of bites that the therapist fed the child if he or she did not self-feed. In the current investigation, we present three case examples to illustrate some challenges we faced when using these procedures outlined in the aforementioned studies and how we addressed these challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A pediatric feeding disorder occurs when an individual fails to eat a sufficient quantity and/or variety of foods/liquids to maintain his or her weight and height (e.g., Hoch, Babbitt, Coe, Krell, & Hackbert, 1994). Feeding disorders may also encompass selective eating where weight and growth are not of concern, but where nutritional status could become compromised. Typically developing eaters finger-feed at about 8 months of age, can use a spoon at about 14 months of age (Carruth & Skinner, 2002), and drink with minimal guidance by 9 to 10 months of age (Pridham, 1990). These skills emerge in most children with minimal assistance from caregivers.

Children with feeding disorders often do not progress to age-typical eating patterns (e.g., self-feeding and self-drinking) in the absence of individualized treatment (Rivas et al., 2014). Even after treatment to increase acceptance of bites fed by others is successful, many children may not demonstrate the necessary skills or motivation to independently feed themselves (Rivas et al.; Vaz, Volkert, & Piazza, 2011). Medical complications (e.g., prematurity, aspiration) often contribute to the initial problems or delays in the development of eating, and prolonged periods of food refusal and abnormal eating routines may explain the failed development of the necessary prerequisite skills required for eating. For example, to self-feed a bite, the child must (1) grasp the fork or spoon, (2) lift the utensil to the lips, (3) deposit the bite inside the mouth, (4) close the lips around the utensil, and (5) pull the bite from the utensil. In addition, children with feeding disorders often lack motivation to take bites independently. Even after food refusal is initially treated, a child with a feeding disorder may lack the motivation to eat due to a biological mechanism (e.g., reduced hunger or satiety cues) and food may not function as a primary reinforcer. This situation becomes especially problematic for caregivers because having to continuously feed the child can be a time-consuming process.

In a literature review, Kerwin (1999) and Volkert and Piazza (2012) identified physical guidance (e.g., hand-over-hand guidance or graduated guidance) often combined with a reinforcement component as the only well-established intervention for increasing self-feeding behavior in individuals with feeding difficulties (e.g., Luiselli, 1988a, b; Luiselli, 1993; O’Brien, Bugle, & Azrin, 1972; Piazza, Anderson, & Fisher, 1993; Sisson & Dixon, 1986a, b). For example, in a study conducted by Luiselli (1988b), for one of the participants, Kay, the feeder placed Kay’s hand around the feeding utensil and together they lifted the utensil to her mouth if she did not take the bite after 40 s. The feeder then removed guidance to allow Kay to place the bite in her mouth. Most of these studies seemed to be addressing skill deficits. The literature on self-drinking is more scarce, and there are only three studies evaluating treatments to increase self-drinking behavior to our knowledge (i.e., Collins, Gast, Wolery, Holcombe, & Leatherby, 1991; Peterson, Volkert, & Zeleny, 2015; Stimbert, Minor, & McCoy, 1977).

More recently, Vaz et al. (2011) and Rivas et al. (2014) raised the question of whether the motivation of children with feeding disorders to self-feed was different from that of children who eat typically. For one participant with food selectivity, Vaz et al. increased self-feeding by identifying a low preference food which they termed the avoidance food (i.e., pureed peas or table-texture peanut butter and jelly) via preference assessment and then providing the child the choice to self-feed one target bite (e.g., table-texture apple) or have the feeder feed him that target bite and five additional bites of the avoidance food. Rivas et al. (2014) conducted a series of manipulations to evaluate the self-feeding behavior of three children with feeding disorders. First, the investigators gave the children the opportunity to self-feed or not eat at all. In this condition, two children never fed and one child rarely self-fed, thereby choosing not to eat all or the majority of the time. Next, the investigators gave the children the opportunity to self-feed a bite of food or be fed a bite of the same food. In this condition, self-feeding was low for two children and variable for the third child. Rivas et al. then evaluated the extent to which increasing the effort associated with being fed by increasing the ratio of therapist-fed to self-fed bites altered self-feeding behavior. The investigators increased the number of bites the therapist fed the child by one across sequential phases until the child began to self-feed or the number of therapist-fed bites was five. Two children began self-feeding when the ratio of self-fed to therapist-fed bites was one to two and one to three, respectively. Levels of self-feeding did not increase for the third child even when the ratio of self-fed to therapist-fed bites was one to five. Thus, the child chose to allow the therapist to feed him five bites of food rather than feed himself one bite of the same food.

For this third child, the investigators manipulated the effort and quality of the therapist-fed bites. A food-preference assessment was used to identify the lowest preference food, again referred to as the avoidance food, of the 16 foods that were the target of the self-feeding treatment. During treatment, the therapist gave the child the opportunity to self-feed a bite of one of the 15 target foods or be fed a bite of the avoidance food. When the child did not self-feed during this arrangement, the investigators increased the number of bites of the avoidance food the therapist fed the child by one across sequential phases. Self-feeding increased to high levels when the ratio of self-fed bites of target food to therapist-fed bites of the avoidance food was one to four.

Although the procedure described by Rivas et al. (2014) and Vaz et al. (2011) offer a method for increasing self-feeding, these procedures may not be effective for every child and may present practical challenges for the implementer. We present case examples to illustrate challenges we faced when using these procedures and strategies used to address these challenges. One challenge that arose was the emergence of problematic behaviors such as packing (pocketing food in the mouth) during treatment. We used swallow facilitation to address this issue. Another problem that can arise is overfeeding due to increases in the volume of therapist-fed food, which might reduce motivation to self-feed and increase the risk of problems such as vomiting. We examined an alternative manipulation (practice trials) that would limit the volume of presented solids and liquids to avoid overfeeding.

Method

Participant, Setting, and Materials

Ezra was a 2-year-old boy diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease and failure to thrive. He was referred initially for poor oral intake and bottle dependence. Mickey was a 4-year-old boy diagnosed with failure to thrive and gastroesophageal reflux disease. He was referred initially for low oral intake. Conor was a 3-year-old boy with a history of failure to thrive. He was referred initially for gastrostomy-tube dependence and food refusal. All participants displayed the dexterity and necessary skills for self-feeding based on direct observation and parental report; however, they did not self-feed consistently in the home or at the clinic. A speech language pathologist and/or physician cleared all participants as safe oral feeders prior to their day-treatment admissions. We treated each child’s primary feeding problem (i.e., food refusal) with a specific, individualized protocol that involved the caregiver feeding the child (i.e., nonself-feeding format). For both Ezra and Mickey, packing was an issue at the outset of treatment. For both children, treatment involved escape extinction (i.e., nonremoval of the spoon), and another component including continuous attention (Ezra), differential reinforcement with a preferred toy (Mickey), and fading from an empty flipped spoon presentation (Sharp, Odom, & Jaquess, 2012) to a flipped spoon presentation of 0.4 cc of yogurt (Ezra) or 0.2 cc of apple sauce (Mickey). For Ezra, we had to combine the above protocol components with blending (Mueller, Piazza, Patel, Kelley, & Pruett, 2004) to increase consumption of nonpreferred foods. For Mickey, once we began introducing variety beyond apple sauce, he continued to pack and we then implemented redistribution combined with swallow facilitation which was not effective (Levin, Volkert, & Piazza, 2014). To re-establish consumption, we implemented escape extinction, differential reinforcement of mouth clean, and a flipped spoon presentation with only apple sauce and then again generalized this treatment to other foods, but it was still difficult to increase the bolus beyond 0.2 cc. Treatment of initial food refusal for Conor consisted of escape extinction and differential reinforcement of mouth clean.

We conducted sessions in a 4-m by 4-m room with one-way observation and sound. Materials in the room included a table and chairs, a scale, age-appropriate seating (e.g., highchair), laptop computers, and timers. Materials used to conduct self-feeding and self-drinking sessions included Gerber® rubber-coated baby spoons, small and large maroon spoons, toddler spoons, nuk brushes, Gerber® plastic bowls, and flexi-cut cups.

Response Measurement and Interobserver Agreement

Trained observers collected data on laptop computers. Observers scored a self-fed acceptance when the child picked up the spoon or cup with his hand(s) and deposited the entire bite or drink, with the exception of an amount the size of a grain of rice for Ezra and Mickey or pea for Conor or smaller inside the mouth within 5 s for Ezra and Mickey or 8 s for Conor of the therapist placing the bowl or cup on the tray. We allowed Conor an extra 3 s to deposit the liquid to account for the time the liquid had to travel from the bottom of the cup and to match the time requirement used by Peterson et al. (2015). Observers scored a presentation when the therapist placed the bowl or cup on the tray in front of and within arm’s reach of the child and said, “Take a bite (drink).” We converted data on self-fed acceptance to a percentage by dividing the total number of bites or drinks accepted within 5 or 8 s of presentation by the total number of presented bites or drinks. Two trained observers independently and simultaneously collected data on self-fed acceptance during 44, 36, and 55 % of sessions for Ezra, Mickey, and Conor, respectively. We calculated interobserver agreement by summing occurrence and nonoccurrence agreements (i.e., total number of 10-s intervals in which both observers either scored or did not score a self-fed acceptance), dividing by the sum of agreements and disagreements (i.e., 10-s interval in which one observer scored self-fed acceptance and the other observer did not), and converting this ratio to a percentage. Mean interobserver agreement was 98 % (range, 90 to 100 %), 96 % (range, 82 to 100 %), and 97 % (range, 79 to 100 %) for Ezra, Mickey, and Conor, respectively.

Summary of Previous Manipulations to Increase Self-fed Acceptance

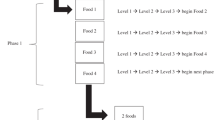

We summarize the data for the unsuccessful self-feeding manipulations we conducted with each child in Table 1 along with a flowchart of the interventions (see Fig. 1). For Ezra, we first examined bite-number manipulations with pureed target foods, in which Ezra had the choice to self-feed a bite of target food or be fed one bite of the same target food by the therapist. We increased the number of bites the therapist fed Ezra from one to five in one-bite increments across sequential phases. Next, we conducted a paired-choice assessment (Fisher et al., 1992) with the target foods and identified the lowest preference target food, waffles, which we used as the avoidance food. In this assessment, if Ezra did not self-feed a bite of target food, the therapist fed him the bite of the same target food and one bite of the avoidance food. When that was ineffective, the therapist fed Ezra the bite of target food and five bites of the avoidance food if he did not self-feed. Next, we increased the texture of the avoidance food from puree to wet ground. If Ezra did not self-feed a bite of pureed target food, the therapist fed him a bite of the same pureed target food and one bite of the avoidance food at a wet ground texture. When that was ineffective, the therapist fed him the bite of pureed target food and five bites of the avoidance food at a wet ground texture if Ezra did not self-feed the bite of pureed target food. This manipulation was not effective; therefore, we initiated the assessment described below.

For Mickey, we first examined bite-number manipulations with pureed target foods, increasing the number of bites the therapist fed Mickey from one to two to five in sequential phases if Mickey did not self-feed the bite of target food. Next, we added practice trials to the bite-number manipulation. If Mickey did not self-feed the bite of target food, the therapist fed him five bites of the target food and then guided him to practice self-feeding. The practice trials consisted of the therapist placing his or her hands over Mickey’s hand and guiding him to grasp the empty spoon, bring the empty spoon to his mouth, and place the empty spoon back in the bowl on the tray. The therapist conducted five practice trials and increased the number of practice trials to 15 in the next phase when five was not effective. We then conducted a paired-choice preference assessment with ten foods chosen by Mickey’s mother (i.e., carrots, crackers, chicken, pineapple, cocktail onions, sardines, brussel sprouts, olives, relish, tuna) to identify sardines as the avoidance food. During treatment, if Mickey did not self-feed the bite of target food, the therapist fed him a bite of sardines. This manipulation was not effective. Therefore, we returned to the condition in which the therapist fed Mickey the bite of target food if he did not self-feed, but the therapist used a flipped spoon to present the target food. During the flipped spoon, the therapist inserted an upright rubber-coated baby spoon into Mickey’s mouth, turned the spoon 180°, and then dragged the bowl of the spoon over the center of his tongue. When this manipulation was not effective, the therapist presented a bite of the avoidance food with the flipped spoon. This manipulation increased self-feeding to high levels, but we were not able to demonstrate functional control. Therefore, we initiated the assessment described below.

For Conor, the therapist offered him the choice of self-feeding 4 cc of a target drink or the therapist feeding him 4 cc of the target drink, but this manipulation was not effective. We did not increase the number of therapist-fed drinks beyond one because of volume concerns; therefore, we added practice trials. If Conor did not self-feed the target drink, the therapist fed him the target drink and then guided him to practice self-drinking. The practice trials consisted of the therapist placing his or her hands over Conor’s hand and guiding him to grasp the empty cup, bring the empty cup to his mouth, and place the empty cup back on the tray. The therapist conducted five practice trials and increased the number of practice trials to 15 in the next phase when five was not effective. When practice trials were not effective, we initiated the assessment described below.

Experimental Design

We used an ABCAC design with Ezra. The baseline was A; B was one self-fed bite versus one therapist-fed bite of the target food and the avoidance food; C was one self-fed bite versus one therapist-fed bite of the target food and the avoidance food with re-distribution and swallow facilitation for packing. We used an ABAB design with Mickey. The baseline was A; B was one self-fed bite versus one therapist-fed bite with flipped spoon presentation. We used an ABABCAC design with Conor. The baseline was A; B was one self-fed drink versus one therapist-fed bite of the avoidance food and one hand-over-hand-fed drink; C was one self-fed drink versus five therapist-fed bites of the avoidance food and one hand-over-hand-fed drink.

Procedure

Prior to this analysis, Ezra and Mickey participated in an intensive day-treatment program for 8 weeks and then transitioned to an outpatient clinic. We conducted the current analysis during Conor’s intensive day-treatment admission. Ezra and Mickey attended weekly 1 to 1.5-h appointments, and we conducted between three and ten sessions during each appointment. The session number varied based on whether we conducted other analyses during the appointment (e.g., caregiver-fed meals). We conducted two to three 30- to 45-min liquid-meal blocks in which the therapist conducted multiple five-drink sessions with Conor per day, and the total number of sessions per day varied between 12 and 20. Trained clinical staff served as therapists for Ezra and Conor, and Mickey’s mother served as the therapist for Mickey. We trained Mickey’s mother to implement the procedure using written instructions (i.e., protocols) and in vivo feedback. Therapists stated the session contingencies to the child one time at the beginning of the appointment or meal block and only repeated the contingencies during the appointment or meal block if we changed the protocol.

General Procedure

Ezra and Mickey’s mothers selected 10 (2 fruits, 2 vegetables, 2 starches, and 4 proteins) and 16 (5 fruits, 4 vegetables, 3 starches, 4 proteins) target foods, respectively, which we presented at a pureed texture. Before each appointment, the therapist who coordinated the treatment selected at least four foods from the complete list to present during the appointment and told the mother which foods to bring. The therapist presented four foods, one from each food group during each session and presented the foods in a quasi-random order, ensuring that he or she presented every food at least once in each phase of the analysis. For Conor, the liquid was chocolate Carnation Instant Breakfast mixed with whole milk.

During each five-bite or drink session, the therapist placed a baby spoon with 0.4 cc for Ezra or a toddler spoon with 0.8 cc for Mickey of food in a bowl or a 4-cc drink on the tray for Conor along with a verbal instruction to “Take a bite or drink.” If the child self-fed the bite or drink, the therapist provided verbal praise (e.g., “Great job taking your bite [drink]”) and removed the spoon and bowl or cup. The therapist prompted the child to “show me” for a mouth-clean check 30 s after the entire bite or drink entered the mouth. If the child did not open his mouth after the verbal and model prompt, the therapist touched a rubber-coated baby spoon at the corner of his lips to guide his mouth to open. The therapist provided praise for mouth clean (no food or liquid larger than a grain of rice for Ezra and Mickey or pea for Conor in his mouth, unless the absence of food or liquid was due to expulsion) or reminded him to swallow (e.g., “You need to finish swallowing your bite [drink]”) if he packed (i.e., food or liquid in the mouth larger than a grain of rice for Ezra and Mickey or pea for Conor). The therapist then placed the next bite or drink on the tray regardless of whether the child swallowed or packed the bite. If the child packed after the fifth bite presentation, the therapist continued checking his mouth every 30 s thereafter until no food or liquid larger than a grain of rice for Ezra and Mickey or pea for Conor remained inside his mouth or 15 min elapsed from the start of the session. If he was still packing at the 15-min cap time, the therapist removed the remaining food or liquid from his mouth with the baby spoon. The therapist provided no differential consequences for negative vocalizations, gagging, or vomiting.

Baseline

The therapist followed the general procedure. The therapist provided no differential attention for inappropriate mealtime behavior (e.g., throwing or knocking the spoon or bowl off of the tray). If Ezra or Mickey dumped the food off of the spoon, threw the bowl and/or spoon, or expelled the bite, the therapist did not retrieve, replace, or re-present the bite and waited to present the next bite at the next scheduled interval (approximately every 30 s). For Conor, the therapist refilled the cup and placed it back on the tray in its original presentation position if he threw the cup or dumped the liquid during the presentation.

Stimulus-Choice Assessment to Identify an Avoidance Food (Ezra and Conor)

Ezra’s mother identified seven foods for inclusion in the paired-choice assessment to identify an avoidance food (i.e., pineapple, relish, sauerkraut, sardines, cocktail onions, brussel sprouts, olives). In addition, we randomly selected four target foods (i.e., yogurt, applesauce, carrots, green beans) for inclusion in the assessment to examine the relative preference of the potential avoidance food relative to the target foods to ensure that the selected avoidance food was less preferred than the target foods. During the preference assessment, the therapist presented two foods with the prompt to “pick one.” The therapist presented each food with every other food and selected the order of pairings randomly. If the child selected a food, the therapist provided brief praise. The therapist then presented the selected food to the child’s lips for 30 s. If the child did not consume the selected food after 30 s or exhibited inappropriate mealtime behavior, the therapist removed the spoon and presented the next pair of foods. If the bite entered the child’s mouth and he packed the bite, the therapist removed the food from his mouth and presented the next pair of foods immediately.

Conor’s mother identified sardines as a potential avoidance food. The procedure was identical to those described above except that the therapist presented 2 cc of sardines on a large maroon spoon and 4 cc of Carnation instant breakfast in a cut-out cup on each trial, and the assessment consisted of ten trials.

During the initial preference assessment, Ezra did not choose any foods. Therefore, we modified the paired-choice procedure as follows. The therapist selected a food from a randomized list and presented it on a nuk brush if Ezra did not choose one of the presented pair of foods or avoided (pushed away) one or both foods. If Ezra or the therapist chose a food, but he did not allow the therapist to deposit the bite within 5 s of presentation, the therapist used nonremoval of the spoon for child-selected foods or nuk for therapist-selected foods in which he or she held the spoon or nuk at Ezra’s lips until Ezra opened his mouth and allowed the therapist to deposit the bite or 30 s elapsed from presentation. The therapist re-presented expelled bites but only did so for 30 s after the bite entered Ezra’s mouth.

General Choice Treatment Procedure

The therapist used the general procedure with the following modifications. If the child did not self-feed the bite or drink, the therapist used nonremoval of the spoon or cup with re-presentation of expelled bites or drinks (Hoch et al., 1994) to feed the number and type of foods specified by the contingency. That is, the therapist held the spoon or cup to the child’s lips using a nonself-feeding format until he or she could deposit the bite or drink in the mouth. The therapist provided no differential consequences for inappropriate mealtime behavior (i.e., head-turning and/or batting at the spoon or cup or the therapist’s hands or arms). When the contingencies involved presentation of multiple bites, the therapist prepared each bite of food and placed them in a bowl located on the table next to him or her, when possible, prior to the bite or drink presentation. The therapist fed the bites to the child in rapid succession, and the data collector activated the 30-s mouth-check timer as soon as the arranged number and type of bites had entered the mouth. If the child expelled (i.e., spit or removed any food or liquid the size of a grain of rice for Ezra and Mickey or pea for Conor or larger from his mouth), the therapist quickly scooped up the expelled bite(s) or drink or retrieved a fresh bite or drink (the therapist approximated the amount and type of expelled food or liquid) if the food contacted an unclean surface (e.g., the floor) and immediately re-presented the bite(s) or drink to his lip.

Food-Type Manipulation (Ezra)

The therapist followed the general choice treatment procedure. If Ezra did not self-feed the bite of target food, the therapist fed him the bite of target food and one bite of the avoidance food. The bolus size for the avoidance food was 0.4 cc on a baby spoon.

Bite-Number and Food-Type Manipulation (Conor)

The therapist followed the general choice treatment procedure with the following modifications. If Conor did not self-feed the 4-cc target drink, the therapist fed him one bite of the avoidance food (i.e., nonself-feeding format) and used hand-over-hand guidance to feed him the drink (placed his or her hands over Conor’s hands, guided him to grasp the cup, brought the cup to his mouth, and placed the cup at his lips until the liquid entered his mouth). In both cases, the therapist used nonremoval procedures. We increased the ratio of self-fed drinks to therapist-fed bites of the avoidance food to one to five when the one-to-one condition was not effective. In this condition, if Conor did not self-feed the target drink, the therapist fed him five bites of the avoidance food and used hand-over-hand guidance to feed him the drink. The bolus size for the avoidance food was 2 cc on a large maroon spoon.

Food-Type Manipulation with Redistribution and Swallow Facilitation (Ezra)

The therapist followed the procedure for food-type manipulation (i.e., one self-fed bite versus one bite of the target food and one bite of the avoidance food fed by the therapist). In addition, the therapist used redistribution and swallow facilitation if Ezra was packing at the 30-s mouth check. That is, the therapist collected the food in Ezra’s mouth with a nuk brush (i.e., a plastic utensil that is approximately 12.5 cm long with soft rubbery bristles at one end) and then placed the nuk brush with the food onto the posterior of his tongue while applying gentle pressure to deposit the food (Levin, Volkert, & Piazza, 2014). We used redistribution and swallow facilitation because Ezra began packing the avoidance food. We hypothesized that Ezra may learn to avoid these procedures by self-feeding the bite of target food because they were aversive or because he was no longer able to evade consumption of the avoidance food when the therapist implemented redistribution and swallow facilitation.

Flipped Spoon Presentation (Mickey)

The therapist followed the general choice treatment procedure (one self-fed bite of the target food versus one therapist-fed bite of the target food) except that if Mickey did not self-feed the target bite, the therapist presented a bite of the target food on a flipped spoon. During the flipped-spoon procedure, the therapist inserted an upright rubber-coated baby spoon into Mickey’s mouth, turned the spoon 180°, and then dragged the bowl of the spoon over the center of Mickey’s tongue. Mickey did not pack food in this assessment, but he had a history of packing that we treated with the flipped spoon with pureed foods and previous assessments to address chewing. We hypothesized that over time the flipped spoon may have acquired aversive properties and Mickey may self-feed to avoid the flipped spoon presentation.

Results

During the paired-choice assessment (data not shown), Ezra self-selected and consumed yogurt (70 % of trials), apple sauce (64 %), and carrots (46 %) and rarely or never self-selected and consumed all other foods. For each food, we examined trials in which the therapist presented that food to Ezra’s lips (i.e., both self and therapist-selected) and calculated the mean percentage of 5-s acceptance and mouth clean and mean rate of expels to identify the avoidance food. We identified brussel sprouts as the avoidance food for Ezra because mean 5-s acceptance and mouth clean were lowest and rate of expels was highest with this food. Conor never selected the sardines during the paired-choice assessment; therefore, we used sardines as the avoidance food.

Figure 2 shows the results of the self-feeding assessment for Ezra (top), Mickey (middle), and Conor (bottom). Ezra’s mean level of self-fed acceptance was 0 % during baseline. Mean levels of self-fed acceptance increased very slightly to 10 % during the one self-fed bite of target food versus one therapist-fed bite of the target food plus one bite of the avoidance food and to 96 % during the redistribution and swallow facilitation condition. Mean levels of self-fed acceptance decreased to 50 % during the reversal to baseline and increased to 80 % during the return to the one self-fed bite of target food versus one therapist-fed bite of the target food plus one bite of the avoidance food with redistribution and swallow facilitation condition.

Mickey’s mean level of self-fed acceptance was 60 % during baseline. Mean levels of self-fed acceptance increased to 93 % during the one self-fed bite of target food versus one therapist-fed bite of the target food with lipped spoon presentation condition. Mean levels of self-fed acceptance decreased to 60 % during the reversal to baseline and increased to 91 % during the return to the one self-fed bite of target food versus one therapist-fed bite of the target food with lipped spoon presentation condition.

Conor’s mean level of self-fed acceptance was 10 % during baseline. Mean levels of self-fed acceptance increased to 68 % during the one self-fed drink versus one therapist-fed bite of the avoidance food with hand-over-hand guidance for the drink. Mean levels of self-fed acceptance decreased to 35 % during the reversal to baseline but were variable during the return to the one self-fed drink versus one therapist-fed bite of the avoidance food with hand-over-hand guidance for the drink condition (M = 58 %). Therefore, we increased the ratio of target drinks to avoidance bites to one to five, which resulted in high levels of self-fed acceptance (M = 74 %). We replicated this effect in a reversal to baseline (M = 48 %) and return to treatment (M = 86 %).

Discussion

The current investigation supports Rivas et al. (2014) and Vaz et al. (2011) in that a history of a feeding disorder may be associated with refusal to self-feed in an age-typical manner. The finding of Rivas et al. (2014) of increased self-feeding with a response effort manipulation with the same food was not replicated. Neither of the participants for whom we manipulated the ratio of self-fed to therapist-fed bites began self-feeding under this arrangement. Rivas et al. (2014) also demonstrated that manipulation of the type of food (introducing a less preferred food as the therapist-fed bit) along with the response effort manipulation improved self-feeding for one child. However, this finding was also not replicated when we implemented this intervention with Ezra in the current study. This failure to replicate the results of Rivas et al. (2014) led us to consider alternative manipulations for increasing self-feeding. We also encountered new challenges as we evaluated these alternative manipulations. In the current study, we used the results of these case examples to demonstrate some possible options for treatment alternatives, the challenges that emerged, and the methods we used to address the challenges.

One problem that we encountered was that there was a limit to the extent to which we could increase the ratio of self-fed to therapist-fed bites or drinks. For example, the bolus size of Connor’s drink was 4 cc, and the approximate volume of liquids a child his age and size consumes at one meal is 237 cc. Conor would have consumed 237 cc in approximately 12 trials if the ratio of self-fed drinks to therapist-fed drinks was 1:5, and the therapist had to feed him on every trial. It would have been inappropriate to increase the volume beyond 237 cc for a variety of reasons (e.g., overfeeding could result in vomiting), and 12 trials would have limited the number of learning opportunities for Conor.

A second problem that was encountered was packing. Ezra began packing when the arranged conditions involved the therapist feeding him bites of the avoidance food. We added redistribution and swallow facilitation with a nuk brush contingent on packing at the 30-s mouth check to reduce packing. Levels of self-feeding increased and packing decreased for Ezra when the therapist used redistribution and swallow facilitation. Although Mickey did not pack food in this assessment, he had previously engaged in packing which was successfully treated with the flipped spoon. We hypothesized that Mickey would avoid the flipped spoon due to his prior history, and the results showed that we could use this procedure to shift responding from being fed to self-feeding. Investigators have hypothesized that swallow facilitation is effective via promotion of skill acquisition (i.e., placement of the bolus on the tongue and stimulation of the swallow response), alteration of motivation (i.e., avoidance of the procedure; Volkert, Vaz, Piazza, Frese, & Barnett, 2011), or both (Gulotta, Piazza, Patel, & Layer, 2005). The results from the current investigation suggest that Ezra and Mickey may have been motivated to avoid the swallow-facilitation procedure as their responding shifted to self-feeding when given the choice to self-feed one bite or to be fed one bite when swallow facilitation was a component of treatment. For Mickey, it is worth noting that we paired the avoidance food with the flipped spoon presentation at one point and it is possible that the flipped spoon presentation gained more aversive properties after we paired it with sardines.

Physical guidance has also been used to increase levels of self-feeding (i.e., physically guiding the child to take the bite if he or she does not take it independently; Luiselli 1988a, b). Although use of physical guidance eliminates escape from eating, it may be difficult to implement in cases where the child is physically strong or has high levels of refusal behavior during the guidance procedure. Therefore, the procedures for Ezra and Mickey used in the current investigation have the advantage of not requiring any physical guidance. However, it is possible that the procedures described in this study could also result in high levels of refusal behavior for some children because of their intrusive nature. We did not observe high levels of refusal behavior with either participant. Ezra (M = 0.64 rpm; range 0 to 4.8 rpm) and Mickey’s (M = 0.23 rpm; range 0 to 2.22 rpm) inappropriate mealtime behavior was low during the treatment phases. Although we used physical guidance with Conor, we do not know if this component was necessary to increase his self-fed acceptance.

We originally sought to replicate the procedures described by Rivas et al. (2014). When we were not successful, we continued to modify our procedures to shift responding to self-feeding. As a result, we did not evaluate positive-reinforcement-based procedures, which is a limitation of the current study. Practitioners should be cautioned to first implement prompting procedures and positive reinforcement to increase self-feeding before attempting the current procedures which are more intrusive in nature. It is possible that using the described manipulations with avoidance foods or potentially noxious stimuli may result in undesirable side effects such as punishing food consumption overall or making foods aversive stimuli. Nonetheless, positive-reinforcement-based procedures may not be effective for some individuals and it important to evaluate alternative procedures if needed as a last resort. Ezra and Mickey’s initial food refusal was difficult to treat due to high levels of packing; thus, it is not surprising that it was equally difficult to increase self-feeding.

One possible limitation is that we did not evaluate the same manipulations in the same order for all children. For example, we did not identify the lowest preference target food to use as an avoidance food with Mickey and Conor. Instead, we identified an avoidance food based on food(s) with more distinctive or pungent flavors nominated by the caregiver. Although using a nontarget food as an avoidance food may be viewed as a more intrusive treatment, we did evaluate practice trials before moving to the avoidance-food procedure. Some caregivers prefer using a novel food rather than a target food as an avoidance food, which was the case with the mothers of Mickey and Conor. If we use a target food as the avoidance food, then we remove that food from the child’s regular diet, which caregivers may be reluctant to do. By contrast, all target foods will remain in the child’s regular diet if we use a novel avoidance food. When given the choice, Mickey and Conor’s mothers elected to use a novel food rather than the lowest preferred target food as the avoidance food to increase self-feeding; however, we did not actually measure social validity for the treatments used in the current study with any of the participants which is a limitation.

For children with feeding disorders, the motivation to eat and self-feed presumably may be low even after these children have acquired the skills to self-feed as indicated in the current study. Future research may want to further explore the use of preference assessments to first identify highly preferred foods to target in self-feeding. After self-feeding of highly preferred foods is established or differentially reinforced, it is possible that self-feeding may generalize to less preferred foods. Antecedent manipulations such as these may ameliorate some of the behaviors encountered in the current study (e.g., packing of the avoidance food). However, in some cases, it may not actually be possible to identify a highly preferred food, which may have been the case for Ezra. Future research should evaluate procedures to establish food as preferred or as a reinforcer.

As previously indicated, having to continuously feed a child with a feeding disorder can be a labor-intensive process. Although the therapist did not have to feed the child each bite using a nonself-feeding format in the current study, he or she did have to manage complicated procedures if the child did not self-feed and this may not promote true independence of self-feeding and be viewed just as time consuming. However, for a child with a life-threatening feeding disorder, it is likely that adult supervision and management of the environment will always be required. Interventions designed to minimize the amount of direct bite administration the adult has to manage will likely help to promote independent feeding by making the meals more feasible and sustainable. We trained Ezra and Conor’s caregivers to implement the self-feeding protocol, but follow-up data are not available. For Mickey, we were able to use the flipped-spoon presentation treatment to increase self-feeding of table food (e.g., self-feed one bite of 0.6 × 0.6 cm piece of table food or therapist fed one bite of same food at puree using a flipped spoon presentation). After self-feeding with table food, we began increasing his consumption of a portion-based meal where we placed a plate of table foods cut into small pieces (one from each food group) in front of him to self-feed. We initiated the portion-based meal without using the avoidance procedure, but after bite number fading and post-meal reinforcement failed, we inevitably had to implement the flipped-spoon presentation contingency to increase consumption of the meal. Future research should evaluate whether this intervention can be generalized from self-feeding single bites, to self-scooping single bites, and eventually consuming an age-appropriate portion and whether the avoidance procedure can be successfully faded from the mealtime.

The procedures used in the current study may help to establish a systematic approach for increasing self-fed acceptance for children with feeding problems whose initial refusal has been treated, who have no motor limitations, but who do not self-feed after positive-reinforcement or antecedent-based interventions have been ineffective. One progression might be to conduct bite-number manipulations with target foods. If this is not successful, the practitioner could conduct a paired-choice assessment to identify the least-preferred target food to use as an avoidance food and then implement bite-number manipulations with the avoidance food. If self-fed acceptance still does not increase, the practitioner could conduct a second preference assessment with more distinctive or pungent novel foods relative to target foods to identify an avoidance food and then implement bite-number manipulations with this avoidance food. If this is still not effective to increase self-fed acceptance and/or packing emerges, the practitioner could conduct a further response-effort manipulation or alter the magnitude of the aversive consequence with swallow facilitation with or without redistribution.

Results of the current study add to the small but growing body of literature to identify treatments to increase self-feeding and self-drinking. The current results extended those of Rivas et al. (2014) and Vaz et al. (2011) and showed that additional alterations to the contingencies associated with being fed were necessary to increase the probability of self-feeding. Although we described a method for practitioners to progress from least to most intrusive treatments to increase self-fed acceptance when manipulations to bite number with target foods are not effective, future research should continue to evaluate when and how to use these variations of response-effort most effectively and ethically.

References

Carruth, B. R., & Skinner, J. D. (2002). Feeding behaviors and other motor development in healthy children (2–24 months). Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 21, 88–96. doi:10.1080/07315724.2002.10719199.

Collins, B., Gast, D., Wolery, M., Holcombe, A., & Leatherby, J. (1991). Using constant time delay to teach self-feeding to young students with severe/profound handicaps: evidence of limited effectiveness. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 3, 157–179. doi:10.1007/bf01045931.

Fisher, W., Piazza, C. C., Bowman, L. G., Hagopian, L. P., Owens, J. C., & Slevin, I. (1992). A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25, 491–498.

Gulotta, C. S., Piazza, C. C., Patel, M. R., & Layer, S. A. (2005). Using food redistribution to reduce packing in children with severe food refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 38, 39–50.

Hoch, T. A., Babbitt, R. L., Coe, D. A., Krell, D. M., & Hackbert, L. (1994). Contingency contacting: combining positive reinforcement and escape extinction procedures to treat persistent food refusal. Behavior Modification, 18, 106–128.

Kerwin, M. E. (1999). Empirically supported treatments in pediatric psychology: severe feeding problems. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 24, 193–214.

Levin, D., Volkert, V. M., & Piazza, C. C. (2014). A multicomponent treatment package to reduce packing in children with feeding and autism spectrum disorders. Behavior Modification, 38, 940–963. doi:10.1177/0145445514550683.

Luiselli, J. K. (1988a). Behavioral feeding intervention with deaf-blind, multihandicapped children. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 10, 49–72. doi:10.1300/j019v10n04_06.

Luiselli, J. K. (1988b). Improvement of feeding skills in multihandicapped students through paced-prompting interventions. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 1, 17–30. doi:10.1007/bf01110553.

Luiselli, J. K. (1993). Training self-feeding skills in children who are deaf and blind. Behavior Modification, 4, 457–473. doi:10.1177/01454455930174003.

Mueller, M. M., Piazza, C. C., Patel, M. R., Kelley, M. E., & Pruett, A. (2004). Increasing variety of foods consumed by blending nonpreferred foods into preferred foods. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis., 37, 159–170. doi:10.1901/jaba.2004.37-159.

O’Brien, F., Bugle, C., & Azrin, N. H. (1972). Training and maintaining a retarded child’s proper eating. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 5, 67–72. doi:10.1901/jaba.1972.5-67.

Peterson, K. M., Volkert, V. M., & Zeleny, J. (2015). Increasing self-drinking for children with feeding disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 48, 436–441. doi:10.1002/jaba.210.

Piazza, C. C., Anderson, C., & Fisher, W. W. (1993). Teaching self-feeding skills to children with Rett syndrome. Developmental Medicine and Child Psychology, 35, 991–996. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.1993.tb11581.x.

Pridham, K. F. (1990). Feeding behavior of 6- to 12-month-old infants: assessment and sources of parental information. Journal of Pediatrics, 117, 174–180. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80016-2.

Rivas, K.M., Piazza, C.C., Roane, H.S., Volkert, V.M., Stewart, V., Kadey, H.J., & … Groff, R.A. (2014). Analysis of self-feeding in children with feeding disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47, 1–14. doi: 10.1002/jaba.170

Sharp, W. G., Odom, A., & Jaquess, D. L. (2012). Comparison of upright and flipped spoon presentations to guide treatment of food refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45, 83–96. doi:10.1901/jaba.2012.45-83.

Sisson, L., & Dixon, M. (1986a). A behavioral approach to the training and assessment of feeding skills in multihandicapped children. Applied Research in Mental Retardation, 7, 149–163. doi:10.1016/0270-3092(86)90002-0.

Sisson, L. A., & Dixon, M. J. (1986b). Improving mealtime behaviors through token reinforcement. Behavior Modification, 10, 333–354. doi:10.1177/01454455860103005.

Stimbert, V., Minor, J., & McCoy, J. (1977). Intensive feeding training with retarded children. Behavior Modification, 1, 517–529. doi:10.1177/014544557714005.

Vaz, P. C. M., Volkert, V. M., & Piazza, C. C. (2011). Using negative reinforcement to increase self-feeding in a child with food selectivity. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 915–920. doi:10.1901/jaba.2011.44-915.

Volkert, V. M., & Piazza, C. C. (2012). Empirically supported treatments for pediatric feeding disorders. In P. Sturmey & M. Herson (Eds.), Handbook of evidence based practice in clinical psychology. Hoboken: Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781118156391.ebcp001013.

Volkert, V. M., Vaz, P. M., Piazza, C. C., Frese, J., & Barnett, L. (2011). Using a flipped spoon to decrease packing in children with feeding disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 617–621. doi:10.1901/jaba.2011.44-617.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

This study was not funded by a grant.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the parent(s) of all children included in the study.

Conflict of interest

Valerie Volkert, Cathleen Piazza, and Rachel Ray-Price declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40617-016-0126-z.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Volkert, V.M., Piazza, C.C. & Ray-Price, R. Further Manipulations in Response Effort or Magnitude of an Aversive Consequence to Increase Self-Feeding in Children with Feeding Disorders. Behav Analysis Practice 9, 103–113 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-016-0124-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-016-0124-1