Abstract

Introduction

Disproportionate rates of psychiatric disorders, like substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders (SUD and PTSD), exist among American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) individuals. This review examines substance use and trauma in existing AI/AN literature and utilizes an AI/AN-specific model to culturally inform the relationship between these factors and provide recommendations for future research.

Methods

We searched three databases through April 2021 for peer-reviewed articles that examined substance use and trauma in AI/AN individuals.

Results

The search identified 289 articles and of those, 42 were eligible for inclusion, including 36 quantitative and 6 qualitative studies. Rates of lifetime trauma exposure varied from 21 to 98% and were correlated with increased rates of SUDs. A dose response of traumatic events also increased the likelihood of an SUD among reservation-based AI populations. Factors from the Indigenist Stress Coping model included cultural buffers such as traditional healing and cultural identity, which aided in recovery from SUD and trauma, and social stressors like boarding school attendance, discrimination, and historical loss.

Conclusions

SUD and trauma are highly correlated among AI/AN individuals though rates of PTSD are lower than might be expected suggesting resilience. However, this pattern may not be consistent across all AI/AN groups and further research is needed to better explain the existing relationship of SUD and PTSD and relevant historical and cultural factors. Further research is needed to culturally tailor, implement, and validate PTSD and SUD assessments and treatments to ameliorate these health inequities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

For American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) people, a range of historical and political factors related to colonization have had a devastating intergenerational impact on AI/AN communities and have led to significant health disparities for Native people [1, 2]. Disproportionate rates of psychiatric disorders, like substance use disorders (SUDs) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), exist among AI/AN individuals. In a national survey, Emerson and colleagues [3] found that 20.2% of AI/AN adults surveyed had past year alcohol use disorder (AUD) compared to 14.2% of non-Hispanic White (NHW) adults, while 22.9% of AI/AN adults had lifetime PTSD compared to 11.7% of NHW adults. In the same study, comorbid AUD and PTSD occurred in 6.5% of AI/AN adults and 2.4% of NHW adults. However, while rates of PTSD are higher among AI/AN, an important consideration is the higher rate of trauma exposure experienced across the lifetime for AI/AN people when compared to other racial/ethnic groups in the US population [4]–[5]. Approximately 80% of AI adults in one community had a traumatic exposure, but the prevalence of PTSD was only observed in 21%, a 4:1 ratio that was comparable to non-AI populations [6]. Similarly, AI/AN individuals are more likely to experience an Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) than NHWs [7, 8] and report the greatest number, average, and variety of ACEs than any other racial/group [9]. Addressing these health inequities requires a culturally relevant approach to understanding the context of PTSD and SUD and the relationship between these two disorders among AI/AN people.

Conceptualizations of mental health development are essential for understanding AI/AN culturally specific models of diagnosis and treatment for SUD and PTSD. Among the general population, existing theories in the literature attempt to explain the relationship between SUD and PTSD but may be problematic for AI/AN populations due to their reliance solely on individual factors, rather than contextual, sociocultural, and historical factors. These theories of shared vulnerability, susceptibility, high-risk, and self-medication hypotheses [10]–[11] have largely been developed and tested in NHW populations and therefore may have limited applicability to diverse groups of individuals with trauma and substance use histories.

The Indigenist Stress Coping model [12] incorporates protective and risk factors specific for AI/AN communities and individuals and recognizes the unique stressors and coping skills applicable within AI/AN cultures. Stressors in the model may include discrimination, historical loss and trauma, and individual trauma factors. Cultural buffers such as community, cultural identity, spirituality, and enculturation are conceptualized as protective against the development of mental health disorders and directly aid in coping with stressors, whether at the individual or community level. The Indigenist Stress Coping model can provide a framework for conceptualizing protective and risk factors for understanding the relationship between substance use and trauma for AI/AN individuals. The Indigenist Stress Coping model provides a more holistic approach that may better illuminate culturally relevant treatment recommendations for AI/AN individuals.

Present Review

This systematic review of quantitative and qualitative literature on trauma and substance use in AI/AN individuals utilized both Western and Indigenous science perspectives. We planned to examine the relationship between trauma exposure or trauma symptoms and substance use in AI/AN samples and assess clinical implications for treating substance misuse and trauma in AI/AN individuals. Additionally, we evaluated the Indigenist Stress Coping model as a model for incorporating AI/AN culturally specific risk and protective factors in the development, diagnosis, and treatment of trauma and substance use. Further, gaps in the current literature and future directions for research are provided.

Methods

Search Strategy and Study Eligibility

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) [13] process, the literature search for articles examining substance use and trauma in AI/AN populations was completed between November 2020 and April 2021. Search terms included the following combinations: (“American Indian” OR “Alaska Native” OR “Native American” OR “Indigenous”) AND (“alcohol” OR “drug use” OR “substance use”) AND (“PTSD” OR “trauma symptoms” OR “trauma exposure” OR “posttraumatic stress”). Electronic databases including PubMed, University of New Mexico Native Health Database, and PsychInfo were searched from earliest year available to April 2021. Manual searches of Google Scholar and ResearchGate were completed based on authors of articles identified in the systematic search. Google Scholar citation alerts were used to identify recently published manuscripts that had not yet been assigned search terms, using the key words “American Indian substance use trauma” and “Alaska Native substance use trauma.” Additionally, reference lists of relevant publications were reviewed to identify eligible articles not identified in our initial search.

Inclusion criteria included peer-reviewed articles in English that presented either qualitative or quantitative data assessing substance use and trauma in an AI/AN sample. Exclusion criteria included non-peer-reviewed publications, editorials, commentaries, letters to the editor; book chapters; non-AI/AN sample; no report of substance use, SUD, trauma exposure, symptoms, or diagnosis of PTSD. Given the immense diversity of Indigenous peoples across the globe, this review is focused specifically on AI/AN populations within the USA.

Methodological Quality

The methodological quality of studies was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [14]. The MMAT includes five categories of study design: qualitative, quantitative randomized controlled trials, quantitative non-randomized trials, quantitative descriptive, and mixed methods resulting in an overall score for each study between 1 and 5. The appraisal criteria include three options: “Yes” (criterion is met), “No” (criterion is not met), and “Can’t tell” (not enough information to assess the criterion). While the original authors discourage a calculation or cutoff score for quality, a score of 1 indicates only one criterion is met and a score of 5 indicates all five quality criteria are met by the study.

Data Extraction

In line with Indigenous research methodologies [15, 16] and previous reviews incorporating Indigenous ways of knowing [17]–[18], data extraction in this review included culturally specific factors framed by the Indigenist Stress Coping model. This process included using qualitative literature to highlight Indigenous voices without critiquing Indigenous knowledge or cultural ways. This is important because it may be more in line with the AI/AN value of including community knowledge without discrediting differences between Western and Indigenous knowledge. For both article types, this included study details (authors, year, title), sample size, population demographics, clinical implications, and information to assess the methodological rigor. Quantitative study extraction categories were tracked in a spreadsheet and included substance use assessment, trauma inciting events, trauma assessment, cultural assessment, use of traditional healing, fit to Indigenist Stress Coping model, and relationship between substance use and trauma. Qualitative study extraction categories included thematic content explaining relationship between substance use and trauma, cultural themes, and use of community-engaged research methods.

Definitions

For the purpose of this review, the term trauma is conceptualized as exposure to traumatic experiences, trauma symptoms, or posttraumatic stress disorder. This review covered individually experienced trauma of AI/AN individuals, not necessarily collective, or racial trauma such as historical trauma, as those were coded as part of the Indigenist Stress Coping model. Measures for trauma exposure in this study included trauma experience checklists such as Childhood Trauma Questionnaire [19], Life Events Checklist for DSM-V [20], and self-reported intimate partner violence. One measure was used for assessing trauma symptoms, the Trauma Symptom Inventory (TSI) [21]. Additionally, studies were coded for PTSD using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-V) [22], or earlier versions of the DSM. Substance use in this review included alcohol and other scheduled drugs including xx?. Studies that assessed nicotine or tobacco use were also included.

Risk and protective factors in the development of mental health diagnoses like substance use and PTSD were coded. As theorized by Walters and colleagues [12], cultural buffers or culturally specific protective factors include identity attitudes, enculturation, spirituality, and traditional healing. Social stressors may include experiencing racism and discrimination, a history of personal or parental attendance at boarding school, and historical or generational trauma. Thus, specific social stressors and cultural buffers were coded to highlight the importance of culturally specific factors in AI/AN presentations of substance use and trauma.

Results

Results presented cover the description of the types of articles reviewed, measurement of substance use and trauma, risk of bias of the studies reviewed, relationship between substance use and trauma, support for the Indigenist Stress Coping model, and treatment factors.

Search Results

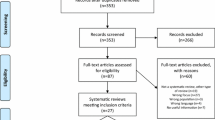

Results of the search and reasons for exclusion are presented in Fig. 1. The search identified 289 articles from the three databases; after removing duplicates, 275 articles remained. The final 42 articles were separated into quantitative (n = 36) and qualitative studies (n = 6) for data extraction.

Demographics of quantitative studies are presented in Table 1 and were diverse in type including both reservation- and urban-based AI/ANs, veteran and civilian populations, and AI/AN youth and adults. Urban-based AI/AN individuals were included in 22% (n = 8) of studies, while reservation or near reservation-based AI/ANs made up 47% (n = 17) of included articles. While many studies use the terminology AI/AN, only two articles specifically included Alaska Native individuals. Populations included 9 clinical samples, 5 veteran samples, and 7 articles contained AI/AN youth in the study sample. Of note, one project, the American Indian Service Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk and Protective Factors Project (AI-SUPERPFP), produced the datasets that made up approximately 20% (n = 8) of quantitative articles. AI-SUPERPFP was a population-based study of two culturally distinct AI reservation communities (Northern Plains and Southwest tribal communities) [23]. Additionally, two studies came from the HONOR project, a multi-site, cross-sectional study on health among two-spirit AI/AN people [24].

Among the six qualitative studies, all were adult samples, two studies recruited urban AI/ANs, one study recruited AN adults, and three studies recruited reservation-based AI individuals. Three studies used focus groups and three studies used individual interviews to gather data from participants. For five of these articles, substance use was the primary focus of inquiry.

Measurement of Substance Use

These articles varied in their focus on types of substances and measurement of substance use. Among quantitative articles, ten (27%) focused only on alcohol use and three only addressed tobacco use. Most articles examined any type of substance use, including alcohol, marijuana, sedatives, tranquilizers, stimulants, analgesics, inhalants, cocaine, hallucinogens (inclusive of peyote), and heroin (n = 23, 63%). None examined drug use (besides tobacco) only. Over 60% of articles measured substance use by assessing for a substance use disorder (n = 22) using various methods to diagnose individuals with either lifetime or past year SUD (see Table 1). Few articles looked at the quantity and frequency of alcohol use, though some included self-reported alcohol use related to heavy drinking (which varied across studies, but generally was 6 or more drinks on one occasion) or number of drinking days. None looked at the quantity or frequency of drug use. No studies commented on the validity or appropriateness of these substance use measures for use among AI/AN populations. Among qualitative articles, alcohol use was the most discussed substance. However, Skewes and Blume [25] reported that methamphetamine use was the most pressing substance use in their collaborating communities over the last 15 years, followed by alcohol use.

Measurement of Trauma

Among quantitative articles, various assessments were used to either diagnose PTSD or measure exposure to traumatic events and are reported in Table 1. Nearly 70% of studies (n = 25) utilized PTSD diagnosis as a metric of trauma. Individuals from the AI-SUPERPFP data were diagnosed with PTSD using the University of Michigan version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) [23]. However, the CIDI was modified for the AI-SUPERPRP project with guidance from community informants to increase the cultural acceptability of resulting diagnoses [23]. Cultural adaptations of assessments, like the CIDI, may more accurately diagnose PTSD among AI/AN compared to standard assessments that have not been validated or adapted to the population. Eight other studies used the CIDI to diagnose PTSD (see Table 1). Two studies utilized the Quick Diagnostic Interview Schedule (Q-DIS) to assess for PTSD in AI veteran samples, though the authors noted this measure has not been validated in the population and may be an underestimate of PTSD [26].

Overall, there was variability in PTSD screening tools and assessment measures utilized, and psychometric validation was limited to two studies reporting reliability in the specific samples utilized. Seven studies utilized seven different screening measures to assess for PTSD diagnosis or the presence of subthreshold PTSD symptomology (see Table 1). None of these measures has demonstrated validity in an AI/AN sample. However, the PTSD Symptoms Scale Self-Report Version showed strong reliability in a sample of rural AI/AN women [27] and Bresleau’s PTSD Short Screening Scale had good reliability among AI/AN adolescents [28].

To measure childhood experiences of trauma, five studies utilized the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ). Two studies utilized items pulled from the ACEs survey. The CTQ has not been statistically validated in AI/AN samples, though Koss and colleagues [29] did report good reliability of the measure in the sample of seven different AI tribes across the USA. Brockie et al. [28] reported fair to good reliability of the CTQ among AI/AN adolescents.

Risk of Bias

Quantitative coding results from the MMAT are presented in Table 1 and qualitative coding results are in Table 2. Among the 36 quantitative studies, 31 were classified as descriptive studies, 2 were RCTs, and 3 were non-randomized studies. All studies scored at least 2 out of the 5 criteria for risk of bias, and all but one study scored a 3 or higher. A lower score is indicative of higher risk of bias using the MMAT. The most common items coded as missed criteria were the appropriate measures and risk of nonresponse bias among quantitative descriptive studies. With respect to qualitative studies, 5 of these six met criteria for 4 items. Overall, most studies included in the review were at low risk for bias.

Relationship Between Substance Use and Trauma

Across study types, for AI/AN individuals and their communities, an association between substance use and trauma was evidenced as outlined in the sections below. Overall, these constructs seem to be co-occurring at high rates across AI/AN individuals at the community level and a common co-occurrence for AI/AN people seeking mental health treatment.

Rates of Trauma and PTSD Across Settings

High prevalence of trauma exposure was reported across clinical samples. Among those entering substance use treatment, there were high rates of lifetime trauma, but a smaller portion were diagnosed with PTSD. Rates of trauma exposure varied between 25.9% of men and 74% of women [30], 84% of women [31] in SUD treatment. Another clinical sample study reported 98% of AI youth experienced a criterion A event, yet only 10.3% met criteria for a diagnosis of PTSD and 13.8% met for subthreshold PTSD [32]. Among AN adults in residential SUD treatment, over 75% of those had a traumatic experience in their lifetime [33]. Additionally, trauma exposure occurred in wide ranges among community samples, 21% of AI youth 15 to 24 from the AI-SUPERPFP sample [34], 44% of urban AI/AN women [35], 61% of AI youth in grades 8 to 11 living on a reservation [36], and 92% of men and 94% of women from a large reservation sample [37].

Across clinical samples, alcohol was the most reported substance used, but polysubstance use was also prevalent. Among youth in SUD treatment, the average number of substances used was 5 and over 80% of those had SUD along with an additional mental health diagnosis. Additionally, youth with a diagnosis of PTSD were more likely to have a stimulant use disorder than other types of SUD [32].

Dose Response

Across multiple studies, the number of traumatic events reported by AI/AN individuals was linked to an increased likelihood of an SUD. Among reservation-based AI youth, an increasing number of traumatic events corresponded with an increased risk for having AUD [34]. Utilizing the same sample but only adults, Libby and colleagues [38] observed this dose response across the lifespan, where AI adults who reported childhood abuse and another traumatic event in adulthood were at increased odds of having an SUD compared to other community members who reported a history of childhood abuse. This dose response pattern also emerged using the CTQ, where reservation-based AI youth with a high number (three to six) of ACEs were 4.6 times more likely to use multiple types of substances than peers with less than three ACEs [28].

Gender differences in the dose response of trauma were reported by Koss et al. [29] where AI reservation-based men who reported three adverse experiences were 4 times more likely to have AUD and women with four or more adverse experiences were 7 times more likely to have AUD. Evidence supporting the dose response of traumatic events related to SUD appears linked to childhood trauma or childhood trauma in combination with trauma experienced later in life among AI people living on reservations.

In contrast, one study with urban AI gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, or two-spirit (GLBTT-S) individuals did not find a dose response of childhood trauma linked to a past year AUD [39]. These findings are inconsistent with other research with AI/ANs that supports the association of multiple traumatic events and substance use, suggesting differential impact of multiple traumatic events for these multiple minority individuals in urban AI/AN communities.

When compared to a non-AI sample, no disparities emerged between the dose response pattern of ACEs and alcohol misuse among AI and non-AI adults surveyed in South Dakota, despite AI individuals being more likely to report more ACEs than non-AI peers [8]. Higher rates of traumatic experiences, but similar rates of alcohol misuse and other mental health concerns, may suggest other unmeasured factors for AI adults that may act as a buffer between higher rates of traumatic exposures but comparable rates of substance use and other mental health concerns with non-AI adults.

Trauma Types Linked to Substance Use and Comorbidity

Type of trauma exposure was correlated with increased rates of substance use and sometimes the type of substance used. Brockie and colleagues [28] found that intimate partner violence most strongly increased the odds of polysubstance use in AI/AN youth. Additionally, in a sample of AI/AN youth in SUD treatment, sexual trauma was most predictive of a PTSD diagnosis [32]. Sexual trauma was also the strongest predictor of binge drinking in the last 6 months for urban AI/AN women [35] compared to other types of criterion A events (e.g., natural disaster, physically attacked, and witnessed death). However, even though sexual trauma may be a strong predictor of SUD among AI/AN people, these trauma types may not be consistent across community groups or gender. For example, among the AI-SUPERPFP sample, childhood physical sexual abuse increased the likelihood of AUD, but only in the Northern Plain AI individuals and not those from the Southwest [38]. Koss et al. [29] found that combined sexual and physical abuse increased likelihood of AUD for AI men, while the combination of sexual assault history and boarding school attendance increased odds for AUD in AI women. Additionally, AI adults who experienced physical injury or assault were 3.5 times more likely to have AUD and 4 times more likely to have a cannabis or stimulant use disorder [37].

Substance Use Context of Trauma

For AI/AN youth, when traumatic events occurred, substance use was often involved. Traumatic events for participants often occurred at a young age, most commonly when the perpetrator of violence was under the influence of alcohol or other drugs [40]–[41]. The context of parental substance use also appears to increase likelihood of childhood trauma; those who reported a parent used alcohol while growing up were more likely to experience multiple traumas in their lifetime than those whose parents did not use alcohol [34].

Self-medication Hypothesis

Qualitative findings supported self-medication theory—the use of substances to cope with symptoms from traumatic experiences. Focus group participants endorsed using substances to cope after experiencing physical or sexual abuse in childhood [42, 43]. Additionally, one study found that childhood sexual assault (CSA) moderated the relationship between depression and a history of alcohol treatment, where those with a history of both CSA and alcohol treatment had higher depression scores. Easton and colleagues [44] interpreted this as supportive of the self-medication theory.

The self-medication hypothesis may be relevant for some AI/AN people who are exposed to trauma at a young age prior to initiation of substance use. Whitesell and colleagues [45] found that individuals who had no symptoms of substance use before a traumatic event were more than twice as likely to report substance use symptoms after a trauma than those who did not experience a traumatic event. While this is not evidence of causality, it implies that adversities often precede substance use. Additionally, those who experienced a traumatic event earlier in their lifetime were more likely to initiate substance use at an earlier age [46].

Support for Indigenist Stress Coping Model

The Indigenist Stress Coping model provided a lens to inform additional culturally specific stressors and buffers that may be relevant to AI/AN individuals with concerns around trauma and substance use.

Cultural Buffers

Among qualitative literature, cultural protective factors, especially spirituality and AI traditional forms of healing, provided healing from traumatic experiences for AI/AN individuals [40]. Cultural and spiritual practices were important in participants’ lives and recovery, as individuals reported enhanced cultural identity, feeling buffered against current and historical stressors, and increased wellness [41]. AI mothers reported that cultural involvement was a tool for recovery from their own substance misuse and trauma. Cultural activities and ceremonies (e.g., Canoe Journey) modeled sobriety and wellness and connected young people to elders and the community broadly [43]. Certain ceremonies and traditional healing also encourage or require sobriety for participation [40, 47]. Additionally, for AN individuals, a traditional lifestyle including involvement in subsistence activity was cited as a protective factor and supportive of leading a sober lifestyle [48].

Cultural buffers were also represented among quantitative literature. As reported by Holm [49], 64% of surveyed AI Vietnam War veterans believed that tribal ceremonies and traditional practices provided healing. Of those who reported recovering from substance use problems associated with PTSD, 41% of AI veterans with alcohol-related problems and 83% of those with drug-related problems reported attending ceremonies. Additionally, 65.7% of those with sleep disturbance and 78.5% of those experiencing flashbacks reported that attending ceremonies resolved these symptoms related to their PTSD [49]. Further, AI women (32%) and AI men (23%) in residential SUD treatment utilized traditional healing within the last year [30].

Social Stressors Specific to AI People

Additional social level stressors were found across quantitative studies including historical loss, boarding school attendance, and discrimination and related to poorer mental health. Among those who attended boarding school, AI youth were more likely to experience a traumatic event [34] and AI women, but not men, were more likely to have AUD [29]. Additionally, among urban-based two-spirit AI/AN adults, those who attended boarding school were more likely to have AUD, and if they were raised by someone who also attended boarding school, they were more likely to report PTSD symptoms [50]. However, for AI women recruited from primary care, boarding school attendance was not related to PTSD or SUD [51]. For AI adolescents aged 15 to 24, increased historical loss symptoms were related to higher rates of substance use and more PTSD symptoms. In the same sample, those who reported more experiences of discrimination, as assessed by an AI-specific discrimination measure [52], were more likely to use substances and have PTSD [28].

Intergenerational Patterns

Multiple studies highlighted the generational patterns of trauma and substance use happening within AI/AN families and communities. Myhra and Wieling [42] found that among families with generational substance use, boarding school attendance in their family was associated with substance use and traumatic experiences. Further, AI women living on a rural reservation noted that their own exposure to violence and substance use was cyclical in nature, both for their own patterns but also passed down through their families [43]. Among AI/AN individuals, parental use of alcohol while growing up was correlated with an increased rate of SUD in two diverse reservation communities [38].

Treatment Factors

Cultural Assessment and Integration

Gathering information about cultural identity during assessment may highlight particular strengths or areas of interest for AI/AN clients entering SUD or PTSD treatment. Commonly reported was the desire for cultural practices and traditional healing to be integrated into treatment options for AI/AN clients (e.g., [40, 42, 43, 47]). Additionally, among AI/AN patients enrolled in aftercare following hospitalization from physical trauma, 33% requested traditional healing while in the hospital and more than half (60%) chose to participate in traditional Native practices following release from the hospital as a way to facilitate the healing process [53].

Beyond individual experiences of trauma, historical trauma was noted as a prevalent factor among AI reservation communities that may hinder healing [25, 40]. Additionally, personal or parental attendance of boarding school predicted substance use outcomes and trauma exposure [29, 34, 50].

Systemic Barriers

Individual level interventions can help identify individual solutions to trauma and substance misuse, but there is a larger system of racism and oppression impacting AI/AN people and communities that hinders recovery and wellness. Under-resourced communities may also need additional infrastructure to support AI/AN youth specifically. Community members noted boredom is often cited as a reason for early experimentation with substances, and there is a need for greater access to prosocial and culturally rich experiences for AI/AN youth and families [42]. Long-lasting and holistic solutions to issues around trauma and substances are needed to improve the health of AI/AN individuals and their communities.

When interviewing tribal members in Montana, Skewes and Blume [25] found that healing or recovery requires intervention on multiple levels; specifically, healing and recovery require intervention at individual, community, family, socioeconomic, and systems levels. Findings also highlighted that provider availability in AI/AN communities, many of which are in underserved or rural locations, may be an additional barrier to care for AI/AN individuals with comorbid SUD and PTSD. Legha et al. [33] reported the use of telepsychiatry to increase provider availability at a tribally operated, urban-based residential SUD treatment clinic serving AN adults with complex treatment needs, particularly medication management.

Existing Treatments for Trauma and Substance Use

One existing evidence-based treatment, Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), was culturally adapted and tested by Pearson and colleagues [27] to target PTSD symptoms, substance use, and HIV sexual risk behaviors in AI women. The culturally adapted CPT included removal of the trauma narrative from CPT, tailoring concepts and handouts to include culturally specific examples and content. Results of the randomized controlled trial found that CPT was effective at reducing alcohol use and PTSD symptoms. While just one example of a treatment for comorbid trauma and substance use concerns, there are substantive takeaways from this work. In particular, the culturally adapted CPT showed promise for use with rural-dwelling AI/AN women presenting to treatment exhibiting PTSD symptoms and wanting to reduce alcohol use. However, only 30% of participants completed the treatment, and 20% dropped out after baseline without receiving any treatment. Strategies to improve treatment engagement for AI/AN clients are warranted given high rates of attrition in treatment.

Discussion

Indigenous Framework to Contextualize Main Findings

Contextualizing the main findings of this review utilizing an Indigenous methodological framework included the use of a culturally specific model to guide findings, the Indigenist Stress Coping model [12], and honoring the personal and experiential aspects of Indigenous traditional knowledge [15]–[17] by including both quantitative and qualitative literature. Utilizing this lens to examine the relationship between trauma and substance use brings light to often overlooked cultural and community factors that may be important for AI/AN individuals with co-occurring trauma and substance use.

Relationship Between Trauma and Substance Use

Qualitative and quantitative findings each supported connections between trauma and substance use but in different ways. Across qualitative literature included in this review, AI/AN community members highlighted that the relationship between trauma and substance use was cyclical, where substance use led to traumatic events and trauma led to substance use among AI/AN individuals. A positive correlation was seen across cross-sectional data that pointed to a dose response of traumatic events that increased the likelihood for SUDs among reservation-based AI individuals [29, 34, 38], but not in a sample of urban-based AI/ANs [39]. In fact, most of AI/AN individuals who presented to SUD treatment had a trauma history, though a smaller proportion met criteria for PTSD. Further, those with a history of childhood trauma and revictimization as an adult were at an increased risk for SUD [38]. Presentation to specialty SUD treatment may be more common for AI/AN individuals, given that no studies included clinical PTSD treatment alone. Additionally, some studies supported the self-medication hypothesis to explain the relationship between traumatic events and substance use in some AI individuals. Given the high rates of trauma across the lifespan and high rates of multiple traumatic events, these studies highlight the importance of treatment options that can address multiple lifetime traumatic events rather than just one traumatic event. Overall, the present review highlighted that the contexts of traumatic events and substance use are intertwined for many AI/AN individuals, at the community level and at clinical levels.

Indigenist Stress Coping Model

Evidence to support the Indigenist Stress Coping model was limited by the sparse measurement of culturally specific buffers and stressors in existing quantitative data. However, qualitative literature indicated that cultural buffers like spirituality, cultural involvement, and access to traditional healing provided support for those moving towards recovery from trauma- and substance use-related distress. Qualitative research also supported the model in that additional stressors increase the likelihood of negative mental health outcomes (like PTSD and SUD) including proximal factors like discrimination and distal factors such as historical and cultural loss tied to boarding schools and colonialism broadly. From quantitative literature, boarding school attendance impacted both alcohol use disorders and PTSD. However, only one study demonstrated a statistical relationship between historical loss and higher PTSD symptoms and SUD [34]. This same pattern also emerged among those who endorsed higher rates of discrimination. Generally, qualitative literature provided more context for the applicability of the Indigenist Stress Coping model to trauma and substance use. However, quantitative work shows some growing evidence to support additional stressors, such as historical trauma and discrimination, that illuminate additional risk to the relationship between substance use and trauma for AI/AN individuals and their communities.

Cultural Considerations in Diagnosis and Treatment

The use of culturally relevant and appropriate instruments to measure trauma and comorbidity is essential for research and treatment with AI/AN individuals. This is particularly relevant for diagnosing PTSD, given that Manson and colleagues [54] found that twice the rate of PTSD was diagnosed by using culturally appropriate instruments compared to national estimates at the time for PTSD in AI/AN people aged 15 to 54. From this review, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview [23] emerged as the only culturally validated measure utilized to diagnose PTSD and SUD. When tailoring the CIDI, Beals and colleagues [23] utilized community stakeholders to provide feedback. They reported changes to screening language like adding cultural idioms of distress and breaking down questions into simpler language. Additionally, assessment of culturally specific stressors may contribute to case conceptualization when working with AI/AN clients [55]. Cultural considerations in measurement are vital for more holistic models that can elucidate understanding of risk and protective factors regarding high rates of trauma and substance use among AI/AN communities.

Furthermore, ongoing systemic stressors and historical stressors were notable in the literature for impacting diagnosis, treatment, and traditional healing for AI/AN individuals across studies. Cultural stressors measured among studies in this review included personal and parental boarding school attendance, discrimination, historical loss and trauma, and intergenerational patterns of trauma and substance use. Relevant protective factors included traditional healing and access to cultural knowledge and spirituality. While these factors may aid the healing process for AI/AN with trauma and substance use concerns, these types of cultural support should come from community not from non-Native providers or organizations. Additionally, not all AI/AN individuals may come from backgrounds where these types of traditions and cultural ceremonies or activities are accessible or appropriate. This accentuates the importance that cultural identity or acculturation be assessed, and client’s desire or willingness to engage or re-engage in culturally specific traditions of healing.

Limitations of the Research

Studies included in this review are primarily from American Indian samples. Given the lack of representation in the literature and the immense diversity of tribes nationally and in Alaska alone, AN people and communities, while grouped together racially with AIs, may have a different presentation. Culturally and historically, AI tribes and AN tribes vary widely, and patterns and observations made in research with AI communities may have limited applicability to AN people and communities. Additionally, individual studies often come from one or a few tribal communities and findings may not be generalizable given the immense diversity of AI/AN tribes and communities.

Some literature examining substance use and trauma are found within the context of articles where the primary aim is often another construct or diagnosis, like conduct disorder [56], depression [44], mood disorders [57], HIV risk [58, 59], or a combination of multiple different diagnoses [28, 60, 61]. In addition, the search terms required both substance use and trauma, so we cannot speak to individuals who have only one or the other. While this provides valuable information on contextual factors that play a role in the relationship between substance use and trauma, these findings limit the generalizeability of these patterns beyond these specific diagnoses.

Methodological problems involving design and measurement hampered confidence in results. Most studies in this review were cross-sectional, limiting interpretation of these findings about the relationship between trauma and substance use in AI/AN people. Given the cross-sectional nature of these quantitative data, no conclusions can be made about a causal relationship between trauma and substance use. The estimates informing this relationship also may not represent a true prevalence of the extent of substance use and trauma in AI/AN communities. Importantly, few articles reported the reliability of trauma or substance use assessments in studies and none tested their validity, so it is unclear how well diagnostic measures performed in the AI/AN samples represented in this review. Psychometric testing of assessment measures are needed to help ensure accurate measurement and interpretation among AI/AN people. Given the stigma around constructs like substance misuse and trauma, these constructs are potentially underestimated in AI/AN individuals and their communities.

Future Directions

Community-Engaged Research

Given the sensitive and potentially stigmatizing nature of substance use and trauma research topics, utilizing community-based approaches, like Indigenous research methods [15, 16] or community-based participatory research [62] may increase community buy in and individual willingness to participate in research on these health inequities, as well as help to ensure appropriate questions, methods, and conclusions. In this review, Skewes and Blume [25] noted that AI community members prefaced knowledge transmission with history and context of their community to researchers to better inform current situations related to trauma and substance use. Research methodologies that utilize community knowledge and build on these resources may better inform culturally relevant constructs in co-occurring PTSD and SUD and illuminate potential treatment targets. Additionally, research with communities should be inclusive of rural, reservation, and urban communities, given that each of these communities have differential access to resources (whether considering healthcare, economic, cultural, or other sources) and thus have different needs when it comes to SUD and PTSD prevention and treatment options. Most research has been focused on AI peoples and reservation-based communities, and additional research is needed on AN and urban communities given the immense diversity of tribes and rurality.

Prevention

Efforts to prevent or intervene with AI/AN youth were a strong theme across qualitative studies given the report of childhood trauma as a factor in substance misuse and trauma later in life [43, 47, 48]. Justifications included youth as an impressionable time, especially because age of onset for substance use is younger among AI/AN youth than for youth of other racial/ethnic groups [63, 64]. Additionally, given that parental substance use was associated with trauma exposure, treatment of SUD for parents may be protective for children and future generations. More longitudinal research is needed to better understand predictors and directionality or circularity of trauma and substance misuse. In addition, research on early intervention following traumatic events in childhood is needed to help reduce these substantive health inequities. Screening and education are vital to addressing these traumas that may be occurring in childhood for AI/AN communities and prevention of further trauma or the development of negative health outcomes like SUDs. The role of cultural protective factors revealed among qualitative literature and in community knowledge should also be further developed in research. Including cultural variables as outcomes, mediators, and moderators in quantitative research, not just as covariates, may help illuminate the relevance of these constructs.

Intervention Development

Among AI/AN communities, there is an immense need for culturally relevant and efficacious treatment to address health inequities, including SUD and PTSD. Interventions that target multiple traumatic events and diagnoses may be particularly relevant. Given high levels of trauma exposure from a young age, focusing on coping skills to deal effectively with trauma may be particularly beneficial. Additionally, cultural tailoring of existing treatment modules such as cognitive restructuring and distress tolerance may improve acceptability, engagement, and outcomes. Examples from the literature include cognitive behavior therapy that has been culturally adapted for AI/AN children exposed to trauma [65], dialectical behavior therapy that has been tailored for AI/AN youth with SUD [66], and motivational interviewing and community reinforcement approach with AI adults [67]. Further, in addition to traditional healing, culturally grounded interventions should be developed to demonstrate cultural and community strengths in processes of healing and broaden accessibility of treatment options for individuals. Individual level interventions are needed for AI/AN people and should include attention to social and cultural factors. Furthermore, the intergenerational patterns of substance misuse and collective trauma may also require broader community level interventions to promote healing and wellness. Finally, efforts to implement tailored evidenced-based treatments in AI/AN community settings are necessary to ameliorate mental health inequities for AI/AN people.

Conclusion

For AI/AN individuals, there is a significant association between trauma exposure early in life and even more if additionally in later life and higher rates of SUDs. However, this pattern may not be consistent across reservation- and urban-based AI/AN people. Further research is needed to better explain the existing association of SUD and PTSD. Utilizing the Indigenist Stress Coping model to incorporate culturally specific risk and protective factors in this relationship found that boarding school attendance, discrimination, and historical loss increased risk while cultural involvement and access to traditional healing buffered the risk and aided in recovery. Further research is needed to validate, culturally tailor, and implement PTSD and SUD assessment tools and treatments to more effectively address these health inequities.

References

Brave Heart MYH, Lewis-Fernández R, Beals J, Hasin DS, Sugaya L, Wang S, et al. Psychiatric Disorders and Mental Health Treatment in American Indians and Alaska Natives: Results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:1033–46.

Gone JP, Hartmann WE, Pomerville A, Wendt DC, Klem SH, Burrage RL. The impact of historical trauma on health outcomes for indigenous populations in the USA and Canada: A systematic review. Am Psychol. 2019;74:20–35.

Emerson MA, Moore RS, Caetano R. Association Between Lifetime Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Past Year Alcohol Use Disorder Among American Indians/Alaska Natives and Non-Hispanic Whites. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2017;41:576–84.

Bassett D, Buchwald D, Manson S. Posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms among American Indians and Alaska Natives: a review of the literature. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(3):417–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0759-y.

Beals J, et al. Trauma and conditional risk of posttraumatic stress disorder in two American Indian reservation communities. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(6):895–905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0615-5.

Robin RW, Chester B, Rasmussen JK, Jaranson JM, Goldman D. Prevalence and characteristics of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a southwestern American Indian community. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(11):1582–8. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.154.11.1582.

Kenney MK, Singh GK. Adverse childhood experiences among American Indian/Alaska Native children: the 2011–2012 national survey of children’s health. Scientifica. 2016;2016:e7424239. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7424239.

Warne D, et al. Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) among American Indians in South Dakota and associations with mental health conditions, alcohol use, and smoking. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28(4):1559–77. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2017.0133.

Richards TN, Schwartz JA, Wright E. Examining adverse childhood experiences among Native American persons in a nationally representative sample: differences among racial/ethnic groups and race/ethnicity-sex dyads. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;111:104812–104812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104812.

Chilcoat HD, Breslau N. Investigations of causal pathways between PTSD and drug use disorders. Addict Behav. 1998;23(6):827–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00069-0.

Windle M. Substance use, risky behaviors, and victimization among a US national adolescent sample. Addict Abingdon Engl. 1994;89(2):175–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00876.x.

Walters KL, Simoni JM, Evans-Campbell T. Substance use among American Indians and Alaska natives: incorporating culture in an “indigenist” stress-coping paradigm. Public Health Rep. 2002;117(Suppl 1):S104-117.

Liberati A, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLOS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100.

Hong QN, et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018;34(4):285–91. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221.

Kovach M. Indigenous methodologies: characteristics, conversations and contexts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2009.

Wilson S. Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. First Edition. Black Point, N.S: Fernwood Publishing; 2008.

Gone JP. Indigenous traditional knowledge and substance abuse treatment outcomes: the problem of efficacy evaluation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(5):493–7. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2012.694528.

Redvers N, Blondin B. Traditional Indigenous medicine in North America: a scoping review. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8): e0237531. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237531.

Bernstein DP, et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(8):1132–6. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132.

Gray MJ, Litz BT, Hsu JL, Lombardo TW. Psychometric properties of the life events checklist. Assessment. 2004;11(4):330–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191104269954.

Briere J, Hedges M. Trauma Symptom Inventory. The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology [Internet]. American Cancer Society; 2010 [cited 2021 Oct 30]. p. 1–2. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy1010.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2017. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

Beals J, Manson SM, Mitchell CM, Spicer P, AI-SUPERPFP Team. Cultural specificity and comparison in psychiatric epidemiology: walking the tightrope in American Indian research. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2003;27:259–89. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025347130953.

Chae DH, Walters KL. Racial discrimination and racial identity attitudes in relation to self-rated health and physical pain and impairment among two-spirit American Indians/Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 1):S144–51. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.126003.

Skewes MC, Blume AW. Understanding the link between racial trauma and substance use among American Indians. Am Psychol. 2019;74(1):88–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000331.

Dickerson DL, O’Malley SS, Canive J, Thuras P, Westermeyer J. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric and substance use comorbidities in a sample of American Indian male veterans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99(1–3):169–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.07.014.

Pearson CR, Kaysen D, Huh D, Bedard-Gilligan M. Randomized control trial of culturally adapted cognitive processing therapy for PTSD substance misuse and HIV sexual risk behavior for Native American women. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(3):695–706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-02382-8.

Brockie TN, Dana-Sacco G, Wallen GR, Wilcox HC, Campbell JC. The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to PTSD, depression, poly-drug use and suicide attempt in reservation-based Native American adolescents and young adults. Am J Community Psychol. 2015;55(3–4):411–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-015-9721-3.

Koss MP, et al. Adverse childhood exposures and alcohol dependence among seven Native American tribes. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25(3):238–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00195-8.

Gutierres SE, Russo NF, Urbanski L. Sociocultural and psychological factors in American Indian drug use: implications for treatment. Int J Addict. 1994;29(14):1761–86. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826089409128256.

Saylors K, Daliparthy N. Violence against Native women in substance abuse treatment. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2006;13:32–51. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.1301.2006.32.

Deters PB, Novins DK, Fickenscher A, Beals J. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology: patterns among American Indian adolescents in substance abuse treatment. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(3):335–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.76.3.335.

Legha RK, Moore L, Ling R, Novins D, Shore J. Telepsychiatry in an Alaska Native Residential Substance Abuse Treatment Program. Telemedicine journal and e-health : the official journal of the American Telemedicine Association. 2020;26:905–11. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2019.0131.

Boyd-Ball AJ, Manson SM, Noonan C, Beals J. Traumatic events and alcohol use disorders among American Indian adolescents and young adults. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19(6):937–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20176.

Walters KL, Simoni JM. Trauma, substance use, and HIV risk among urban American Indian women. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 1999;5(3):236–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.5.3.236.

Jones MC, Dauphinais P, Sack WH, Somervell PD. Trauma-related symptomatology among American Indian adolescents. J Trauma Stress. 1997;10(2):163–73. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1024852810736.

Ehlers CL, Gizer IR, Gilder DA, Yehuda R. Lifetime history of traumatic events in an American Indian community sample: heritability and relation to substance dependence, affective disorder, conduct disorder and PTSD. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(2):155–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.10.002.

Libby AM, et al. Childhood physical and sexual abuse and subsequent alcohol and drug use disorders in two American-Indian tribes. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65(1):74–83. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2004.65.74.

Yuan NP, Duran BM, Walters KL, Pearson CR, Evans-Campbell TA. Alcohol misuse and associations with childhood maltreatment and out-of-home placement among urban two-spirit American Indian and Alaska Native people. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(10):10461–79. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111010461.

Jervis LL. Disillusionment, faith, and cultural traumatization on a Northern Plains reservation. Traumatology. 2009;15(1):11–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765608321069.

Myhra LL, Wieling E. Psychological trauma among American Indian families: a two-generation study. J Loss Trauma. 2014;19(4):289–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2013.771561.

Myhra LL, Wieling E. Intergenerational patterns of substance abuse among urban American Indian families. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2014;13(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2013.847391.

Schultz K, Teyra C, Breiler G, Evans-Campbell T, Pearson C. ‘They gave me life’: motherhood and recovery in a tribal community. Subst Use Misuse. 2018;53(12):1965–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2018.1449861.

Easton SD, Roh S, Kong J, Lee Y-S. Childhood sexual abuse and depression among American Indians in adulthood. Health Soc Work. 2019;44(2):95–103. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlz005.

Whitesell NR, et al. The relationship of cumulative and proximal adversity to onset of substance dependence symptoms in two American Indian communities. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91(2–3):279–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.008.

Whitesell NR, Beals J, Mitchell CM, Manson SM, Turner RJ. Childhood exposure to adversity and risk of substance-use disorder in two American Indian populations: the meditational role of early substance-use initiation. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70(6):971–81.

Myhra LL. “It Runs in the Family”: Intergenerational Transmission of Historical Trauma among Urban American Indians and Alaska Natives in Culturally Specific Sobriety Maintenance Programs. AIANMHR. 2011;18:17–40. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.1802.2011.17.

Mohatt GV, Rasmus SM, Thomas L, Allen J, Hazel K, Hensel C. ‘Tied together like a woven hat:’ protective pathways to Alaska native sobriety. Harm Reduct J. 2004;1(1):10–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-1-10.

Holm. The National Survey of Indian Vietnam Veterans. AIANMHR. 1994;6:18–28. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.0601.1994.18.

Evans-Campbell T, Walters KL, Pearson CR, Campbell CD. Indian boarding school experience, substance use, and mental health among urban two-spirit American Indian/Alaska natives. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(5):421–7. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2012.701358.

Duran B, Malcoe LH, Sanders M, Waitzkin H, Skipper B, Yager J. Child maltreatment prevalence and mental disorders outcomes among American Indian women in primary care. Child Abuse and Neglect; 2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.06.005.

Whitbeck LB, Chen X, Hoyt DR, Adams GW. Discrimination, historical loss and enculturation: culturally specific risk and resiliency factors for alcohol abuse among American Indians. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65(4):409–18.

Tsosie U, Nannauck S, Buchwald D, Russo J, Trusz SG, Foy H, et al. Staying Connected: A Feasibility Study Linking American Indian and Alaska Native Trauma Survivors to their Tribal Communities. Psychiatry: Interpersonal & Biological Processes. 2011;74:349–61. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2011.74.4.349.

Manson SM, Beals J, Klein SA, Croy CD. Social epidemiology of trauma among 2 American Indian reservation populations. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(5):851–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.054171.

Hernandez-Vallant A, Herron JL, Fox LP, Winterowd CL. Culturally relevant evidence-based practice for therapists serving American Indian and Alaska Native clients. Behav Ther. 2021;44(3):149–55.

Kunitz SJ, Levy JE, McCloskey J, Gabriel KR. Alcohol dependence and domestic violence as sequelae of abuse and conduct disorder in childhood. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22(11):1079–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00089-1.

Libby AM, Orton HD, Novins DK, Beals J, Manson SM. Childhood physical and sexual abuse and subsequent depressive and anxiety disorders for two American Indian tribes. Psychological Medicine. Cambridge University Press; 2005;35:329–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291704003599.

Pearson CR, Kaysen D, Belcourt A, Stappenbeck CA, Zhou C, Smartlowit-Briggs L, et al. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and HIV Risk Behaviors Among Rural American Indian/Alaska Native Women. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2015;22:1–20. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.2203.2015.1.

Simoni JM, Sehgal S, Walters KL. Triangle of risk: urban American Indian women’s sexual trauma, injection drug use, and HIV sexual risk behaviors. AIDS Behav. 2004;8(1):33–45. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:aibe.0000017524.40093.6b.

Sawchuk CN, Roy-Byrne P, Noonan C, Bogart A, Goldberg J, Manson SM, et al. Smokeless tobacco use and its relation to panic disorder, major depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder in American Indians. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2012;14:1048–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr331.

Sawchuk CN, Roy-Byrne P, Goldberg J, Manson S, Noonan C, Beals J, et al. The relationship between post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and cardiovascular disease in an American Indian tribe. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:1785–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntv071.

Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839906289376.

Stanley LR, Swaim RC. Initiation of alcohol, marijuana, and inhalant use by American-Indian and white youth living on or near reservations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;155:90–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.009.

Whitesell NR, Beals J, Crow CB, Mitchell CM, Novins DK. Epidemiology and etiology of substance use among American Indians and Alaska Natives: risk, protection, and implications for prevention. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(5):376–82. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2012.694527.

BigFoot DS, Schmidt SR. Honoring children, mending the circle: cultural adaptation of trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for American Indian and Alaska Native children. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66(8):847–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20707.

Beckstead DJ, Lambert MJ, DuBose AP, Linehan M. Dialectical behavior therapy with American Indian/Alaska Native adolescents diagnosed with substance use disorders: combining an evidence based treatment with cultural, traditional, and spiritual beliefs. Addict Behav. 2015;51:84–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.07.018.

Venner KL, Serier K, Sarafin R, Greenfield BL, Hirchak K, Smith JE, et al. Culturally tailored evidence-based substance use disorder treatments are efficacious with an American Indian Southwest tribe: an open-label pilot-feasibility randomized controlled trial. Addiction; 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15191.

De Ravello L, Abeita J, Brown P. Breaking the cycle/mending the hoop: adverse childhood experiences among incarcerated American Indian/Alaska Native women in New Mexico. Health Care Women Int. 2008;29(3):300–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330701738366.

Howard MO, Walker RD, Suchinsky RT, Anderson B. Substance-use and psychiatric disorders among American Indian veterans. Subst Use Misuse. 1996;31(5):581–98. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826089609045828.

Laudenslager ML, et al. Salivary cortisol among American Indians with and without posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): gender and alcohol influences. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23(5):658–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2008.12.007.

Mylant M, Mann C. Current sexual trauma among high-risk teen mothers. Journal of child and adolescent psychiatric nursing : official publication of the Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nurses, Inc. 2008;21:164–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2008.00148.x.

Walker RD, Howard MO, Anderson B, Lambert MD. Substance dependent American Indian veterans: a national evaluation. Public health reports (Washington, DC : 1974). 1994;109:235–42.

Westermeyer J, Canive J. Posttraumatic stress disorder and its comorbidities among American Indian veterans. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49(6):704–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-012-9565-3.

Beals J, Novins DK, Whitesell NR, Spicer P, Mitchell CM, Manson SM. Prevalence of mental disorders and utilization of mental health services in two American Indian reservation populations: mental health disparities in a national context. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(9):1723–32. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1723.

Davis KC, Stoner SA, Norris J, George WH, Masters NT. Women’s awareness of and discomfort with sexual assault cues: effects of alcohol consumption and relationship type. Violence Women. 2009;15(9):1106–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801209340759.

Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(11):1259–64. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259.

Stewart SH, Conrod PJ. Psychosocial models of functional associations between posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorder. Trauma and substance abuse: Causes, consequences, and treatment of comorbid disorders. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 29–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/10460-002.

Ka’apu K, Burnette CE. A Culturally Informed Systematic Review of Mental Health Disparities Among Adult Indigenous Men and Women of the USA: What is known? Br J Soc Work. 2019;49:880–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcz009.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (T32 AA018108, PI: Witkiewitz). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism,T32 AA018108,Jalene Herron,National Institute on Drug Abuse,R34040064,Kamilla L. Venner,UG1 DA049468,Kamilla L. Venner,R61DA049382,Kamilla L. Venner

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Venner has a conflict to disclose, as she provides training and consultation in evidence-based treatments for fee. She has a COI management plan at UNM.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Herron, J.L., Venner, K.L. A Systematic Review of Trauma and Substance Use in American Indian and Alaska Native Individuals: Incorporating Cultural Considerations. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 10, 603–632 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01250-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01250-5