Abstract

Background

Despite considerable achievements associated with the MDGs, under-five mortality, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, remains alarmingly high. Globally, intimate partner violence (IPV) affects one in three women within their lifetime. Little is known about the relationship between IPV and maternal care-seeking in the context of high rates of under-five mortality, particularly among young women and adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Methods

Data from the Kenya Demographic Health Survey (2008–2009) were limited to a sample of women aged 15–24 years (n = 1406) with a child under-five who had experienced IPV in the last 12 months. Using multivariate logistic regression, we constructed three models: (1) base model, (2) controlling for type of residence (urban/rural), and (3) controlling for wealth status and education attainment, to estimate odds ratios (ORs) for the association between IPV and 10 maternal care-seeking behaviors.

Results

Thirty-eight percent of the women had experienced some form of intimate partner violence in the last 12 months. Women who had experience IPV were less likely (1) to complete a minimum of four antenatal visits after single IPV exposure (OR = 0.61, 95% CI = 0.44, 0.86) and after severe IPV (OR = 0.80; 95% CI = 0.44, 0.88) and (2) to deliver in health facility after severe IPV exposure (OR = 0.74; 95% CI = 0.54, 0.89), both adjusted for educational attainment and wealth status. Lower socioeconomic status and living in a rural area were strongly associated with increased likelihood of IPV.

Conclusions

Intersectional approaches that consciously focus on and creatively address IPV may be key to the success of reducing child mortality and improving maternal health outcomes. The implementation of joint programming and development of combination interventions to effectively reduce the risk of exposure to IPV and promote maternal care-seeking behavior are needed to improve child morbidity and mortality in LMICs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is increasing global recognition that intimate partner violence (IPV) is a critical public health concern impacting the lives and health of millions of women and adolescent girls worldwide. IPV has been recognized by the United Nations as a human rights challenge (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS 2004). The World Health Organization (WHO) defined IPV as “behavior within an intimate relationship that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm, including acts of physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse and controlling behaviors” (WHO 2010). In 2014, The Global Fund launched a new initiative, the Gender Equality Strategy: Action Plan 2014–2016, which prioritizes reducing gender-based violence and strengthening efforts to address sexual and reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health (Global Fund/UN 2014).

According to a 2014 WHO study of 81 countries, prevalence of exposure to IPV is 29.4% among adolescent girls age 15–19 years and 31% among women age 20–24 years (Devries et al. 2013). Women’s experience of IPV has been associated with younger age, poverty, lower educational attainment, alcohol abuse, exposure to maltreatment, attitudes towards acceptance of violence, marital discord, and educational disparity between partners (Hall et al. 2014). In addition, IPV has been linked as a key contributor to increased disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) from depression, self-harm injuries, violence, and HIV (Haagsma et al. 2016).

Under the millennium development goals, the United Nations prioritized poverty, under-five mortality (U5M), and women’s empowerment—with a focus on girls (United Nations 2015). Commitment to these goals has been strengthened under the new sustainable development goals 1, 3, and 5 and emphasizes the urgent need to understand and reduce IPV and its impact on children’s health, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where 50% of all adolescent births (15–19 years) worldwide occur in sub-Saharan Africa and where IPV prevalence (36.6%) is alarmingly high and the majority of under-five deaths (81 per 1000 live births) occur worldwide (WHO 2013, 2016; Devries et al. 2010; United Nations 2014).

Globally, one third of all women have experienced IPV at some point in their lives (Dunkle et al. 2004). Numerous studies have documented the relationship between IPV and women’s reproductive health, maternal health, mental health, and birth outcomes (Hall et al. 2014; Meiksin et al. 2015; Ellsberg et al. 2008; Silverman et al. 2006; UNWomen 2015). Also, compared to women who are not in abusive relationships, women who are exposed to IPV reported higher rates of risky sexual behaviors, increasing their risk for acquiring HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (Jewkes et al. 2010). Recent evidence suggests that women in abusive relationships are less likely to obtain adequate prenatal care. In Timor-Leste, a study of ever-married women found IPV was associated with decreased maternal care-seeking behavior and increased child morbidity and mortality (Meiksin et al. 2015).

Kenya, the location of this study, has one of the highest IPV prevalence rates in the world (Devries et al. 2011; UNWomen 2012). According to the 2014 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS), 38% of ever-married women aged 15 to 49 years experienced IPV, while the under-five mortality rate was 74 deaths per 1000 live births (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics [KNBS] and ICF Macro 2010). Although Kenya is committed to reducing child mortality, the number of children who die each year from preventable childhood diseases, e.g., pneumonia, malaria, and diarrhea, remains alarmingly high. Given the high prevalence of IPV and under-five mortality, coupled with negative maternal care-seeking behavior, IPV could be an important target for U5M policy and prevention intervention programs.

Using the most recent publicly available data from the 2008–2009 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey, we examined the association between IPV (physical and sexual abuse) and direct and indirect maternal care-seeking behavior, within the context of high under-five mortality rates. The aims of this study were to: (1) examine the relationship between IPV and maternal care-seeking behavior and (2) to determine whether young women who experience IPV are more likely to experience negative maternal care-seeking behaviors. We aim for these findings to be of use to government policymakers and health professionals in Kenya and the broader international public health community as they target limited resources to improve maternal health and decrease child morbidity and mortality. To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale population study of young women and adolescent girls (15–24 years) in sub-Saharan Africa to examine maternal care-seeking and the experience of intimate partner violence to explore under-five mortality by examining specific dimensions of maternal care-seeking behavior.

Methods

Sample

This study utilized data from the 2008–2009 KDHS, a nationally representative sample survey of 8444 women age 15 to 49 years and 3465 men age 15 to 54 years, selected from 400 clusters throughout Kenya (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) and ICF Macro International 2010). Women respondents were asked questions on the following topics: demographics (e.g., religion, education, age, place of residence), as well as birth history, prenatal care, family planning, and exposure to domestic violence. They were also asked to provide information on maternal care-seeking behavior, including responses to illness and treatment practices within the last 2 weeks.

To analyze maternal care-seeking behavior in relation to IPV, we abstracted data from the household survey for 1406 ever-married women (15–24 years) with a child born on or after January 2003. Analyses were restricted to ever-married women to better understand how IPV operates within conjugal arrangements. For this study, we used publicly available data acquired through the MEASURE DHS website (IFC Macro International 2010). The 2008–2009 KDHS was approved by the Institutional Review Board of IFC Macro International in compliance with the rules and regulations of US Department of Health and Human Services as it relates to the protection of human subjects and vulnerable populations.

Outcome Variables

For this study, 10 maternal care-seeking behaviors were investigated:

- i.

Attendance to Antenatal Care was defined in this study as having had a minimum of four antenatal visits during the last birth (WHO 2014).

- ii.

Delivered in Health Facility was defined as having delivered the most recent child at a health facility.

- iii.

Received Post-natal Checkup was defined as receiving post-natal checkup within 2 months of giving birth.

- iv.

Received Immunization was defined as having received any vaccinations for disease prevention.

- v.

Received Diarrhea Treatment was defined as using oral rehydration salts (ORS) for treatment of diarrhea.

- vi.

Obtained Health Card was defined as having obtained a health card for most recent child.

- vii.

Used Insecticide Treated Bed Nets (ITNs) was defined as a child sleeping under a bed net.

- viii.

Received Pneumonia Treatment was defined as use of antibiotics for treatment of pneumonia.

- ix.

Received Antimalarial Treatment was defined as use of any of the following antimalarial drugs: SP/Fansidar, Chloroquine, Amodiaquine, Quinine, combination with Artemisinin, or other for treatment of malaria.

- x.

Obtained Health Insurance was defined as having access to health insurance.

Independent Variables

Independent variables in this study were selected based on existing literature on maternal care-seeking behavior. Educational attainment was defined as number of years of schooling. It was coded as a three-level variable: (i) zero years, (ii) one-six years, and (iii) six or more years. The wealth index is a proxy for socioeconomic status derived from the following household assets: (1) ownership of consumer goods, (2) dwelling characteristics, (3) type of drinking water source, (4) toilet facilities, and other characteristics related to household socioeconomic status. Each asset was assigned a weight (factor score) generated using principal component analysis. Next, each household was assigned a cumulative score for each asset. Individual respondents were ranked according to the total score of the household in which they resided, and these scores were then used to construct a wealth index divided into quintiles: (i) poorest, (ii) poorer, (iii) middle, (iv) richer, and (v) richest. Type of residence was defined as residing in an urban or rural area and recorded as a dichotomous variable (rural = 0, urban = 1).

Intimate Partner Violence was defined as an ever-married woman who had experienced physical violence or sexual abuse by a spouse or partner. Respondents were asked in the 12 months preceding the survey if any of the following had been committed by their husband/partner:

- 1.

Push you, shake you, or throw something at you?

- 2.

Slap you?

- 3.

Twist your arm or pull your hair?

- 4.

Punch you with his fist or something that could hurt you?

- 5.

Kick you, drag you, or beat you up?

- 6.

Tried to choke you or burn you on purpose?

- 7.

Threaten or attack you with a knife, gun or any other weapon.

- 8.

Physically force you to have sexual intercourse with him even when you did not want to?

- 9.

Force you to perform sexual acts you did not want to?

An IPV index was calculated using the IPV questions above. The IPV index is a composite measure of a woman’s cumulative exposure to IPV. Respondents who answered “yes” to any of the nine IPV items were coded as experiencing IPV. Individuals were ranked on the basis of their cumulative IPV score, and a three-level categorical variable was generated to determine experience of physical and/or sexual IPV: (i) no IPV exposure, (ii) moderate exposure—single IPV event, and (iii) severe exposure—two or more IPV events.

Statistical Analysis

In the descriptive analysis, we conducted univariate analysis of ever-married women 15–24 years of age with a child under-five (Table 1). Next, we conducted univariate analysis of ever-married women 15–24 years with a child who had no experience of IPV compared to those with one or more exposures. In Table 2, we fitted three multivariate models from the ever-married subsample to estimate odds ratios (ORs) for associations between intimate partner violence (IPV index) and 10 maternal care-seeking behaviors. The first model (base model) included only IPV index (not shown). The second model was adjusted for type of residence (urban/rural) and the third model adjusted for major socioeconomic variables (i.e., wealth status and education level). Before additional adjustments were performed, a variance inflation factor (VIF) statistic was calculated to ensure no multicollinearity existed. All analyses were performed using Stata v.14. (StataCorp 2013). All analyses were weighted to account for selection, probability, non-response, and sampling differences between regions.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Demographic and Health Surveys repository located at http://www.dhsprogram.com/Data/ (Silverman et al. 2006).

Results

Descriptive Analysis

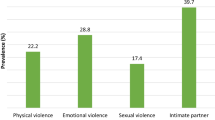

Of the sample of ever-married women aged 15–24 years with a child under-five (n = 1406), the majority of respondents were between the ages of 20–24 (85.4%) with a mean age of 22.1 years. The number of children under-five ranged between 1 and 6 children (mean = 1.8), with the majority (44%) having one child. More than two thirds (71.2%) of women resided in rural areas. The majority (60.3%) of respondents had at least some primary education (Table 1). Almost 40% (37.9%) of the women had experienced some form of intimate partner violence in the last 12 months. Almost a quarter (24.1%) of the respondents had been slapped; 13% had been pushed or shook or had something thrown at them; 9.3% had been dragged or kicked, and 10.5% had been physically forced to have sex. In addition, Table 1 disaggregates the background data examining differences between young women who had no experience of IPV and those who had one or more exposures to IPV. We found that 31% of the women in the poorest wealth quintile reported one or more exposures compared to only 18.3% of those in the wealthiest quintile. Also, women with a secondary education and beyond had fewer exposures to IPV (15.8%) compared to women with a primary school education (21.8%). And women residing in rural areas (73.7%) were more likely to experience IPV than their urban counterparts (26.3%). Among women who reported one or more exposures to IPV, being slapped (27.9%) was the most common. Also, we found that women who had experienced IPV were less likely to engage in positive maternal care-seeking behavior in all categories. For example, women who had no experience of IPV were more than twice (69.7%) as likely to attend a minimum of four antenatal visits compared to women with one or more IPV exposures (30.3%).

Among ever-married women (15–24 years) with a child under-five, the majority (82.4%) of the children had obtained a health card, 64.8% slept under ITNs, and 58.9% delivered in a health facility. However, a significant number of women with children under-five reported negative maternal care-seeking behavior. Only 4.6% of mothers reported use of antimalarial drugs for treatment of malaria; 8.1% reported using ORS to treat diarrhea; 30.9% had a post-natal check within 2 months of delivery; 21.8% had ever been vaccinated; 25.2% used antibiotics to treat pneumonia; and only 44.2% had attended at least four antenatal visits.

Multivariate Analysis

We examined the association between IPV and 10 maternal care-seeking behaviors (Base Model). Compared to women with no IPV exposure, women exposed to IPV had decreased rates of vaccination, attending at least a minimum of four antenatal visits, delivering in health facility, having children who slept under ITNs or receiving post-natal check within 2 months of delivery. When controlling for type of residence (urban/rural) (Table 2/Model 1), the association remained significant between IPV and ever had a vaccination for a single (moderate) IPV exposure (OR = 0.52; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 027, 0.78) and attended a minimum of 4 antenatal visits for single IPV (OR = 0.60; 95% CI = 0.42, 0.86) and for two or more (severe) IPV exposures (OR = 0.76; 95% CI = 0.53, 0.93). Young women who experienced severe levels of IPV were 28% less likely to have delivered in a health facility (OR = 0.72; 95% CI = 0.54, 0.96). The odds of having a post-natal check within 2 months of delivery was almost twice as likely for severe IPV exposure (OR = 1.77; 95% CI = 1.18, 2.65).

Using a regression model to control for wealth and educational attainment (Model 2), the association between IPV and a minimum of four antenatal visits remained statistically significant for ever-married young women who experienced IPV at single IPV exposure (OR = 0.61; 95% CI = 0.44, 0.86) and at severe IPV (OR = 0.80; 95% CI = 0.44, 0.88). Also, we found a negative association between IPV and delivering in a health facility for severe exposure to IPV (OR = 0.74; 95% CI = 0.54, 0.89). There was also an association between receiving post-natal care within 2 months of delivery and severe IPV (OR = 1.81; 95% CI = 1.18; 2.78). After controlling for wealth status, educational attainment, and work status, there was no statistically significant association between IPV and use of ORS for treatment of diarrhea, use of ITNs, having a health card, ever vaccinated, use of antibiotic for treatment for pneumonia, use of antimalarial drugs, or having health insurance.

Model 2 displays a trend towards more positive maternal care-seeking behaviors, e.g., ever had vaccination, attending at least four antenatal visits, delivered in health facility, and having a health card among respondents in higher wealth quintiles. After controlling for socioeconomic status, young women and adolescent girls in the wealthiest quintile were more likely than women in the lowest quintile to engage in positive maternal care-seeking behavior. Compared to ever-married women (15–24 years) with a child under-five in the poorest quintile, women in the wealthiest quintile were almost three times more likely to attend at least four antenatal visits (OR = 2.50; 95% CI = 1.49, 4.15), deliver in a health facility (OR = 5.51; 95% CI = 9.64), and obtain a health card (OR = 3.14; 95% CI = 1.98, 4.32). Similarly, we found that educational attainment was significantly associated with several maternal care-seeking behaviors. Women with more than 6 years of schooling were more likely than women with no education to attend a minimum of four antenatal visits (OR = 1.91; 95% CI = 1.23, 2.96), deliver in a health facility (OR = 7.55; 95% CI = 4.60, 10.40), obtain a health card (OR = 2.10, 95% CI = 1.31, 3.44), and receive post-natal check within 2 months of delivery (OR = 7.97; CI = 3.24, 10.34). Moreover, residing in an urban area had a strong protective effect against negative maternal care-seeking behavior in all 10 dimensions. In a follow-up analysis, we examined another set of models where we stratified the data on two sociodemographic variables: (i) wealth status (low vs high wealth status) and (ii) education (low vs high educational attainment). However, we do not report these models because it presented similar results to model 2, and due to the smaller sample sizes in some categories, we were unable to generate results.

Discussion

Our study detected an association between maternal care-seeking behavior and IPV among young women ages 15–24 years in Kenya. Women who had experienced IPV were significantly less likely to attend a minimum of four antenatal visits and delivery in a health facility—both positive maternal care-seeking behaviors associated with improved maternal and child health outcomes. Contrary to our expectations, IPV was not significantly associated with use of antibiotics for pneumonia, access to a health card, having health insurance, treatment of diarrhea with ORS, or use of ITNs. Lower socioeconomic status was strongly associated with IPV, suggesting that poverty may increase IPV among young women and adolescent girls and influence their maternal care-seeking behavior. In our sample, 71.2% of respondents resided in rural areas and 36.1% had experienced one or more IPV events in the last 12 months. Rural status had a significant negative effect on maternal care-seeking behavior on all 10 dimensions. IPV was also inversely associated with post-natal health check within 2 months of delivery. According to the 2008–2009 Kenya DHS, 53% of all women surveyed received a post-natal check within 2 months of giving birth (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) and ICF Macro 2010). However, when disaggregated by age, younger women had greater access to post-natal care. Among young women less than 20 years of age, 37.2% had a post-natal check compared to 27.2% among women 35–49 years. Additional studies are needed to understand and clarify mechanisms for observed associations and the influence of aggravated exposure to IPV during the pregnancy period, particularly the pre-natal and post-natal phases of pregnancy.

In sub-Saharan Africa, and particularly in Kenya, gender inequities inscribed in family law, including differential rights in child custody, property, and sociocultural practices related to pregnancy and child care, can have negative consequences for maternal and child health (Hatcher et al. 2013). In addition, extreme poverty and lack of access to education may foster conditions that reinforce social norms and attitudes that tolerate or promote IPV. In Kenya, a qualitative study showed that IPV also had a material aspect which has been referred to as “economic violence” (Newberger et al. 1992). Young mothers who live in poverty, with little or no education and lack familial support, often fear being expelled from the marital home and the loss of financial support engendering an environment which may reinforce existing societal norms around IPV in intimate settings.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action signed by 189 countries to prioritize women’s empowerment and gender equality (Dunkle et al. 2004). The SDG goals 1, 3, and 5 build on progress towards millennium development goals 1, 4, and 5 to improve women’s empowerment and maternal and child health. Despite growing recognition of the importance of reducing gender-based violence, IPV continues at alarming levels. The strength of this study is the regional focus on sub-Saharan Africa where some of the highest rates of IPV occur and under-five mortality remains disturbingly high. The association between exposure to IPV among young women and adolescent girls (15–24 years) and decreased rates of attending a minimum of four antenatal visits and delivering in hospital highlights the potential impact IPV prevention interventions could have upon child morbidity and mortality.

Challenges and Limitations

The generalizability of the findings was constrained by the data and design limitations. The current study was a cross-sectional study which does not allow us to infer causality; however, it does provide important preliminary data on an understudied population and the role of IPV on maternal care-seeking behavior. Since we constricted the sample by age (15–24 years) and mothers with a child under-five, it limited our ability to potentially detect significant associations for other possible maternal seeking behavioral outcomes impacting women. Despite these shortcomings, we were able to detect associations between IPV and maternal care-seeking behavior on two dimensions. Also, limited sample sizes for ever-married women with a child under-five who experienced IPV within the last 12 months precluded our ability to control for temporal consistency. Temporal bias is a particular problem inherent to cross-sectional studies limiting our ability to ascertain whether the exposure precedes the outcomes tested. While limiting our sample to a timeframe of birth outcomes and IPV within the last 12 months may mediate temporal bias, it does not fully eliminate it. Additionally, these studies are susceptible to recall bias limiting reliability and complete accuracy. Finally, we were constrained by the measurement of IPV (ever having experienced physical or sexual abuse), which did not allow us to design potentially more appropriate survey questions to better understand how the unique circumstances surrounding pregnancy may heighten exposure of young women to IPV. These limitations notwithstanding, the analysis provides evidence that for at least some of the outcomes IPV may be related to the pregnancy experience.

Conclusions

Our analysis on the association between IPV and maternal care-seeking behavior provides insights for future policy development regarding IPV as it relates to women’s empowerment, poverty, and maternal and child health policy and programs (SDG goals 1, 3, and 5). The study highlights three priority strategies to complete the unfinished agenda of the MDGs: (1) informing policy, (2) developing prevention interventions, and (3) future research. As the SDGs are being implemented, we offer the following recommendations:

Recommendation 1: Ministry of Health National Health Development Plans should implement a systems-level approach to IPV. It is critical that governments recognize IPV as a national priority and set policies and systems to identify and manage patients, train staff, monitor and evaluate IPV data, and provide feedback on both process and outcomes. The implementation of a systems-level approach will help address barriers to IPV screening including time constraints, non-existent or poorly implemented protocols and policies, lack of and/or poorly trained staff, and inconsistent standards of care that may conflict with IPV screening recommendations and policies. The implementation of an integrated approach at multiple levels throughout the health delivery system offers considerable potential to identify IPV and reduce under-five mortality rates.

Recommendation 2: Successful implementation of maternal and child health programs to reduce infant mortality and under-five mortality should require universal IPV screening and counseling for women. IPV and its association with negative pregnancy-related maternal care-seeking behavior underscore the need for increased IPV screening and counseling and prevention interventions. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has recommended IPV screening and counseling for all adolescent girls and adult women (Miller et al. 2015). Primary prevention efforts within a systems-based model should include routine IPV screening and linkage to IPV-related support and advocacy resources regardless of disclosure.

Recommendation 3: IPV screening and counseling services should be integrated as part of maternal and child health programs. Our findings suggest a link between IPV and negative maternal care-seeking behavior around the pregnancy experience. Antenatal clinics are a logical contact point for integrating routine IPV screening and services along with maternal and child health services and support for vulnerable populations, particularly young women and adolescent girls. Studies have shown differential rates in IPV identification by the type of facility with increased identification in obstetrical clinics compared to emergency rooms (O’Doherty et al. 2014). Moreover, the pregnancy period may be a key entry point in the process of interrupting and repairing trauma associated with intergenerational transmission of IPV. Studies have shown that a brief IPV advocacy intervention may reduce abuse and improve maternal mental health in pregnant women (Rivas et al. 2015).

Recommendation 4: The provision of a trained cadre of IPV advocates is an essential component in the successful implementation of a systems-level approach to IPV. Critical to creating a sustainable system change is the provision of healthcare facility-based IPV advocates who possess the necessary training and expertise to identify IPV victims, assess the level of exposure to IPV, provide emotional counseling and support, develop safety/protection plans, and facilitate referrals to community-based advocacy programs. IPV counseling and support services may include individually tailored counseling sessions for pregnant women; one-to-one advocacy interventions, individual cognitive-based therapy, and couples counseling/group couples therapy, and women’s empowerment training. Research has shown that access to an IPV advocate increases the likelihood of identification of IPV and referral for needed services (Feder et al. 2011).

Recommendation 5: To ensure successful implementation of IPV screening services, it is essential to develop effective, appropriate training programs that incorporate healthcare personnel perspectives. Lack of training has been shown to be a major barrier to IPV detection and outreach among healthcare personnel. Additionally, in low- and middle-income countries where IPV is embedded in cultural norms, it is highly likely that some of the healthcare personnel tasked with IPV screening are or have been victims of IPV (Mitchell et al. 2013). Because of their lived experience with IPV and knowledge regarding barriers and facilitators to identification of IPV, healthcare personnel are best prepared to provide potential solutions to mitigate barriers to IPV screening. Training curriculum for IPV advocates should challenge prevailing cultural and social norms supportive of violence as well as provide IPV screening and services for healthcare personnel. Moreover, in settings where time and/or resource constraints and lack of personnel are common, task-sharing/shifting mechanisms may help to mitigate barriers to implementation of IPV screening programs and services.

Recommendation 6: Primary prevention strategies should be prioritized to address the root causes of IPV. The root causes of IPV are complex and differ across settings and populations. However, the relative position of women compared to men and the normative use of violence in a society have been shown to be primary risk factors for IPV (Jewkes 2002). Promotion of safe, nurturing and healthy relationships, and access to IPV prevention information and advocacy should be an essential component of standard care in primary-care settings. Additionally, social marketing strategies such as posters, pamphlets, and local radio programs as well as school-based curriculum and interventions that educate and create awareness around gender-based violence and promote gender equality can help to improve the status of women and change social norms around IPV.

Recommendation 7: Structural-level interventions should be a part of a systems-based approach to IPV. Greater access to economic and educational opportunities may address both structural (macro-economic policy) and individual (sociodemographic) factors that increase a woman’s exposure to IPV and limit her ability to access healthcare for herself and her children. Structural-level IPV interventions have been shown to reduce IPV, controlling behaviors; improve economic outcomes; enhance relationship quality, empowerment, and social capital; disrupt norms around acceptability of IPV; and increase health-seeking behaviors (Bourey et al. 2015).

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DALYs:

-

Disability-adjusted life years

- DHS:

-

Demographic and Health Surveys

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IPV:

-

Intimate partner violence

- ITNs:

-

Insecticide-treated nets

- UNAIDS:

-

Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS

- KDHS:

-

Kenya Demographic and Health Survey

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- MDGs:

-

Millennium development goals

- MICs:

-

Multi-indicator cluster surveys

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- ORS:

-

Oral rehydration salts

- SDGs:

-

Sustainable development goals

- U5M:

-

Under-five mortality

- VIF:

-

Variance inflation factor

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- YLD:

-

Years lived with disability

- YLL:

-

Years of life lost

References

Bourey, C., Williams, W., Bernstein, E. E., & Stephenson, R. (2015). Systematic review of structural interventions for intimate partner violence in low- and middle-income countries: organizing evidence for prevention. BMC Public Health, 15, 1165. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2460-4.

Devries, K. M., Kishor, S., Johnson, H., Stöckl, H., Bacchus, L. J., et al. (2010). Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: analysis of prevalence data from 19 countries. Reproductive Health Matters, 18, 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0968-8080(10)36533-5.

Devries, K., Watts, C., Yoshihama, M., Kiss, L., Schraiber, L. B., Deyessa, N., WHO Multi-Country Study Team, et al. (2011). Violence against women is strongly associated with suicide attempts: evidence from WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women. Social Science and Medicine, 73, 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.006.

Devries, K. M., Mak, J. Y. T., Garcia-Moreno, C., Petzold, M., Child, J. C., Falder, G., Lim, S., Bacchus, L. J., Engell, R. E., Rosenfeld, L., Pallitto, C., Vos, T., Abrahams, N., & Watts, C. H. (2013). The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science, 340, 1527–1528.

Dunkle, K., Jewkes, R. K., Brown, H. C., Gray, G. E., McIntryre, J. A., & Harlow, S. D. (2004). Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. The Lancet., 363, 1415–1421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4.

Ellsberg, M., Jansen, H. A., Heise, L., Watts, C. H., & Garcia-Morena, C. (2008). Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic health: an observational study. The Lancet, 371(9619), 1165–1172. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X.

Feder, G., Davies, R. A., Baird, K., Dunne, D., Eldridge, S., Griffiths, C., Gregory, A., Howell, A., Johnson, M., Ramsay, J., Rutterford, C., & Sharp, D. (2011). Identification and Referral to Improve Safety (IRIS) of women experiencing domestic violence with a primary care training and support programme: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 378(9805), 1788–1795. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61179-3.

Haagsma, J. A., Graetz, N., Bolliger, I., Naghavi, M., Higashi, H., Mullany, E. C., … Vos, T. (2016). The global burden of injury: incidence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and time trends from the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. Injury Prevention, 22(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041616.

Hall, M., Chappell, L. C., Parnell, B. L., Seed, P. T., & Bewley, S. (2014). Associations between intimate partner violence and termination of pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 11(1), e1001581. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001581/.

Hatcher, A., Romito, M., Odero, M., Bukusi, M. O., & Turan, J. M. (2013). Social context and drivers of intimate partner violence in rural Kenya: implications for the health of pregnant women. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15(4), 404–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.760205.

IFC Macro International. (2010). The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS)-Datasets. Rockville, MD. 2010. Retrieved from http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

Jewkes, R. (2002). Intimate partner violence: causes and prevention. The Lancet, 359(9315), 1423–1429. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08357-5.

Jewkes, R. K., Dunkle, K., Nduna, M., & Shai, N. (2010). Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and evidence of HIV infections in young woman in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet, 376, 41–48.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, United Nations Population Fund and United Nations Development Fund for Women. (2004). Women and HIV/AIDS: confronting the crisis. Retrieved from http://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/women_aids.pdf.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) and ICF Macro. (2010). Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008–09. Calverton, Maryland: Retrieved from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr229/fr229.pdf.

Meiksin, R., Meekers, D., Thompson, S., et al. (2015). Domestic violence, marital control, and family planning, maternal, and birth outcomes in Timor-Leste. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19, 1338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1638-1.

Miller, E., McCaw, B., Humphreys, B. L., & Mitchell, C. (2015). Integrating intimate partner violence assessment and intervention into healthcare in the United States: a systems approach. Journal of Women’s Health, 24(1), 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2014.4870.

Mitchell, V., Parekh, K. P., Russ, S., Forget, N. P., & Wright, S. W. (2013). Personal experiences and attitudes towards intimate partner violence in healthcare providers in Guyana. International Health, 5(4), 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/iht030.

Newberger, E. H., Barkan, S. E., Lieberman, E. S., McCormick, M. C., Yllo, K., Gary, L. T., & Schechter, S. (1992). Abuse of pregnant women and adverse birth outcome. Current knowledge and implications for practice. Journal of the American Medical Association, 267(17), 2370–2372.

O’Doherty, J., Taft, A., Hegarty, K., Ramsay, J., Davidson, L. L., & Feder, G. (2014). Screening women for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings: abridged Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal, 348, g2913.

Rivas, C., Ramsay, J., Sadowski, L., Davidson, L. L., Dunne, D., Eldridge, S., Hegarty, K., Taft, A., & Feder, G. (2015). Advocacy interventions to reduce or eliminate violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well-being of women who experience intimate partner abuse. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, 12, CD005043. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005043.pub3.

Silverman, J. G., Decker, M. R., Reed, E., & Raj, A. (2006). Intimate partner violence victimization prior to and during pregnancy among women residing in 26 U.S. states: associations with maternal and neonatal health. American Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology, 195, 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2005.12.052.

StataCorp. (2013). Stata statistical software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. Retrieved from https://www.stata.com/stata13/.

The Global Fund/United Nations. (2014). Gender equality strategy: Action plan 2014–2016. Retrieved from http://www.globalfundadvocatesnetwork.org/resource/gender-equality-strategy-action-plan-2014-2016/#.VmibRrgrL6Q.

United Nations. (2014). United Nations General Assembly. Report of the Open Working Group of the General Assembly on Sustainable Development Goals. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/68/970&referer=/english/&Lang=E.

United Nations. (2015). The Millenium development goals report 2015. United Nations, New York. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20(July%201).pdf.

United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women). (2015). Summary Report: The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action turns 20. Retrieved from http://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2015/02/beijing-synthesis-report.

Unitied NationsWomen. (2012). Violence against women prevalence data: surveys by country. Retrieved from http://www.endvawnow.org/uploads/browser/files/vawprevalence_matrix_june2013.pdf.

World Health Organization. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85239/1/9789241564625_eng.pdf.

World Health Organization. (2016). Sexual and reproductive health factsheet. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/maternal/adolescent_pregnancy/en/.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2014). Antenatal care recommendations. United Nations. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/gho/maternal_health/reproductive_health/antenatal_care_text/en/.

World Health Organization/London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. (2010). Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: taking action and generating evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44350/1/9789241564007_eng.pdf.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) for providing technical and logistical support.

Funding

This project was supported by NIH Research Training Grant #R25 TW009345 awarded to the Northern Pacific Global Health Fellows Program by the Fogarty International Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PB contributed to the study conception and design, drafting of manuscript, and acquisition of the data; JZ and MK provided critical revision; BH, BW, and DO contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, and CB contributed to conception and design of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study utilized the 2008–2009 KDHS and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of IFC Macro International in compliance with the rules and regulations of US Department of Health and Human Services as it relates to the protection of human subjects and vulnerable populations.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burns, P.A., Zunt, J.R., Hernandez, B. et al. Intimate Partner Violence, Poverty, and Maternal Health Care-Seeking Among Young Women in Kenya: a Cross-Sectional Analysis Informing the New Sustainable Development Goals. Glob Soc Welf 7, 1–13 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40609-017-0106-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40609-017-0106-4