Abstract

Background

The Barthel Index is one of the most employed questionnaires for the evaluation of functionality, but there is no information on its psychometric properties.

Objective

The aim was to evaluate the reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Spanish version of the Barthel Index.

Methods

The data employed in this paper were obtained from four Spanish cohorts of elderly people of 60 years or older. We collected data on age, gender, education level, comorbidities, and questionnaires regarding functionality, health-related quality of life, depression, and social support.

Results

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were greater than 0.70. The confirmatory factor analysis provided satisfactory fit indexes and factor loadings. The correlation coefficients between the Barthel Index and the other questionnaires were lower than the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. Known-groups validity showed significant differences in the Barthel Index according to age, number of comorbidities, and gender. The standardized effect size and the standardized response mean were between 0.68 and 1.81.

Discussion

This version of the Barthel Index has good reliability, its structural validity has been confirmed, and the questionnaire can discriminate between groups and detect changes at follow-up points.

Conclusions

This questionnaire can be used in the evaluation of functionality and basic activities of daily living in elderly people with different conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The evaluation of the functionality is essential in studies of frailty and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in the elderly. In fact, functional disability is one of the most important predictors of several outcomes, such as mortality, use of health services, or falls [1, 2], and, at times, it is considered to have more predictive capacity than other traditional variables [3].

When studying functional disability, different approaches and measurement strategies have been used. One of those strategies is the evaluation of activities of daily living (ADL) [4]. ADL refers to the everyday tasks that we perform when we are independent, and these are often divided into basic activities of daily living (BADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) [2].

Several questionnaires have been developed for the measurement of BADL [4], but the BI [5] is one of the most accepted and generally used in studies of functional capacity in the elderly [6].

The Barthel Index (BI) was initially developed to measure the level of functional independence of patients with neuromuscular and musculoskeletal pathologies [5], but it has been employed in other conditions [6, 7]. The review performed by Cabañero-Martínez et al. in 2009 [1] determined the scarcity of data on its psychometric properties, although it has been used in many studies of disability and it is still employed in current practice. In its Spanish version, only Baztán et al. [7] reviewed its characteristics, but they did not evaluate its validity and reliability with real data.

Any outcome measurement must comply with several characteristics before we can trust in its results. The aim of this paper was to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the BI and its functioning in four cohorts of elderly people.

Methods

The data employed in this paper came from four different cohorts. The first two were obtained from a study that included 2102 patients of 65 years or older who were recruited in the emergency departments (EDs) of six public hospitals in Spain [8, 9]. These patients were admitted with a hip (Cohort 1, 1008 patients) or wrist (Cohort 2, 1094 patients) fracture because of a fall. Patients were excluded if they had physical or psychological impairments that would prevent them from properly completing the questionnaires. Six months after the fracture, follow-up questionnaires were sent to all of the participants by mail. The participants who did not return the materials were sent a reminder letter at 21 days and again at 35 days, if necessary. After that, the participants who still had not returned the materials were telephoned to increase the response rate.

The third cohort (Cohort 3) came from a nationwide, cross-sectional study on HRQoL in 234 people 60 years and older who were living in 17 residential care settings across Spain [10]. Patients were excluded if they had moderate or severe cognitive impairment, which was operationally defined as four or more errors, adjusted by education level, in the Short Portable Mental State Questionnaire [11].

Cohort 4 included 1106 community-dwelling people of 65 years or older who were recruited from across Spain by a geodemographically based proportional multistage stratified sampling method [12]. These people were interviewed in their homes regarding health and HRQoL.

In all cases, the subjects were informed of the goals of each study and provided informed consent to participate. Approvals from the Ethics Committees and/or Review Boards of the participating institutions were obtained.

For the sake of the analysis of this paper, the following variables that were present in all of the studies were included in the analysis: age, gender, education level, comorbidities, and the questionnaires described below.

The BI [5] was used in all of the studies to assess functional status. It measures the ability to perform 10 BADL. The item scores are summed to yield a total score that range from 0 (totally dependent) to 100 (completely independent). A Spanish version of the BI was used [7].

Other questionnaires in Cohorts 1 and 2

The 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) [13] measures general HRQoL. The scores are transformed into the physical component score (PCS-12) and mental component score (MCS-12). Each of these subscales is scored from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing better function.

The Lawton and Brody Index (LBI) [14] was used to measure IADL. We used the dichotomous format provided by Lawton and Brody [14] because of its simplicity. Higher scores indicate greater ability.

The QuickDASH (only for Cohort 2) consists of 11 items derived from the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) questionnaire, which is an instrument designed specifically for upper-extremity disability [15]. Scores are converted to a range of 0 (no disability) to 100 (most severe disability). The QuickDASH has been shown to be equally reliable and valid as the full DASH [16].

The self-administered Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index questionnaire (WOMAC) [17] (Cohort 2) is a health status instrument specific for patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis. We used a Spanish short-form of the questionnaire (WOMAC-SF) [18], which covers two dimensions: pain (PD-W) and function (FD-W). The scores for each dimension were standardized to range from 0 to 100, with 0 representing the best health status possible and 100 representing the worst.

Other questionnaires in Cohorts 3 and 4

The EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D) gives an overall value of the HRQoL based on five questions regarding the state of health [19]. Each item is rated on a three-level scale from 1 (no problem) to 3 (inability to perform or extreme problem).

The Functional Independence Scale (FIS) (Cohort 4) measures functional independence in several activities of daily living [20]. Higher scores indicate greater functional independence.

The depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D) is a self-report measure developed to screen depression in non-psychiatric patients [21] (Cohort 4). It consists of seven items rated on a 0–3 Likert-type scale. Thus, the total possible score ranges from 0 to 21.

The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support (DUFSS) measures an individual’s perception of personal social support [22] (Cohort 4). It is composed of 11 items, answered on a 5-point scale. The score ranges between 11 and 55, with higher scores indicating greater perceived social support.

Statistical analysis

All the analyses were performed separately in the four cohorts, except responsiveness, which was analyzed only in Cohorts 1 and 2.

The statistical description of the sample was performed using means and standard deviations (SDs) or frequencies and percentages. Sociodemographic data and BI were compared among the four cohorts of patients. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Scheffe’s test for multiple comparisons or the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare continuous variables, and the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables.

Reliability was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient [23]. A coefficient >0.70 was considered acceptable [24].

The structure validity was evaluated by means of a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for categorical variables to confirm the structure proposed by the original authors [5]. Various indexes of fit were evaluated [25]: (a) the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), in which a value <0.08 was considered acceptable; and (b) the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), both of which had to be >0.90 to be satisfactory. Factor loadings were also examined, and those ≥0.40 were considered suitable.

The convergent and discriminant validity of the BI were explored by its correlations with the questionnaires described above. Regarding convergent validity, we expected high correlations with PCS-12, LBI, QuickDASH, the items of self-care, and mobility for the EQ-5D, FIS, and HADS-D. For discriminant validity, we sought to find lower correlations with MCS-12, PD-W, and DUFFS.

For known-groups validity, we expected that the BI would capture the differences between participants divided by different criteria: (a) age (≤75, 75–85 and >85 years); (b) number of comorbidities (0, 1–2 and ≥3); and (c) gender. Following the results found in other studies and/or our experience, we hypothesized that the BI score would be lower (greater dependency) for older people [26], those with more comorbidities [27] and for women. Therefore, the BI scores were compared among the different subgroups using the t test or the ANOVA with Scheffe’s test for multiple comparisons or using the non-parametric Wilcoxon or Kruskal–Wallis tests.

The predictive validity was analyzed by studying the ability of the Barthel Index to predict mortality at 6 months by means of the area under the ROC curve (AUC). Further, to establish the optimal cut-off value of the Barthel Index for this prediction, the ROC analysis was used considering the one that maximized the sum of sensitivity and specificity. This analysis was performed in patients with hip or wrist fracture.

Regarding responsiveness, we first compared sociodemographic characteristics and baseline BI between patients who responded to the follow-up and those who did not. We used the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for the comparison of categorical variables, and the t test or the non-parametric Wilcoxon test for quantitative variables. Then, among responders, the responsiveness study was performed separately according to groups defined by the change score obtained in the LBI as follows: those patients with LBI at baseline equal or lower than at follow-up were classified as “unchanged or improved” and those with LBI at baseline higher than at follow-up were considered “worsened.” We decided to combine the improved and the unchanged patients because the first group was small in both cohorts, and the change scores were similar to the unchanged group.

The means and SDs were calculated for the BI at baseline and at the 6-months, and a paired t test was used for the comparison of scores at the two time points. Ceiling and floor effects at baseline and at 6 months were examined to evaluate the acceptability of the scales. We used 15% as the critical value [28]. To measure the responsiveness, we used the standardized effect size (SES) and the standardized response mean (SRM) [29]. Cohen’s benchmarks were used to classify the magnitude of the effect sizes [30]: not significant, <0.20; small, 0.20‒0.50; moderate, 0.50‒0.80; and large, >0.80. We expected a larger SES or SRM in patients who were classified as “worsened” than among those classified as “unchanged or improved.”

All statistical analyses were performed with SAS for Windows statistical software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and Mplus version 6.1 software (Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles).

Results

The descriptive data of the four cohorts are presented in Table 1. The mean age ranged between 72.07 years for Cohort 4 and 83.66 years for Cohort 1. The majority of the participants were women, and most of the participants had comorbidities, particularly in Cohort 3, in which almost 80% of the participants had 3 or more comorbidities.

Reliability

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were all greater than 0.70: 0.92 for Cohorts 1 and 3, 0.91 for Cohort 2, and 0.92 and 0.88 for Cohort 4.

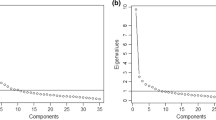

Confirmatory factor analysis

The fit indexes of the CFA satisfied the thresholds in all of the cohorts. The RMSEA was below 0.08 in all cases, and the CFI and TLI values were all above 0.90.

All of the factor loadings were above 0.40 and were statistically significant (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Convergent and discriminant validity

The discriminant validity was confirmed. For Cohort 1, the correlation between the BI and MCS-12 was 0.20 and that between the BI and PD-W was −0.25. For Cohort 2, the correlation between the BI and MCS-12 was also low (r = 0.20). Finally, in Cohort 4, the BI and the DUFFS showed a correlation of r = 0.10.

Regarding the convergent validity, the highest correlations were found between the BI and the LBI in Cohorts 1 and 2 (r = 0.76 and r = 0.58, respectively), the FD-W and PCS-12 in Cohort 1 (r = 0.73 and r = 0.57, respectively), and with EQ-5D, in the self-care item, in Cohort 3 (−0.66) (Table 3).

Known-groups validity

More dependency was observed in the older people in all of the cohorts, except the third one (p = 0.7098). As age increased, the BI scores decreased, and the differences were significant between all age groups (Table 4).

Similar results were observed with comorbidities: as the number of comorbidities increased, the BI decreased. The differences were statistically significant in Cohorts 1, 2, and 4.

The hypothesis for gender was only confirmed in Cohort 3, in which women scored significantly lower than men.

Predictive validity

The AUC of the Barthel Index for the prediction of mortality at 6 months in patients with hip fracture was 0.674, and the optimal cut-off value was 85, obtaining a sensitivity of 63.64% and a specificity of 64.77%. In patients with wrist fracture, the AUC was 0.739, with an optimal cut-off value of 90 resulting in a sensitivity of 58.82% and specificity of 83.98%. Considering both hip and wrist fracture patients together, the AUC was 0.742, with a sensitivity and specificity of 79.05 and 61.93%, respectively, corresponding to a cut-off value of 95.

Responsiveness

Differences between the respondents and non-respondents were only found in Cohort 1. In this group, respondents had a higher education level and higher scores in the PCS-12 and lower scores in the PD-W and the FD-W than non-respondents.

Although the floor effects were low, the ceiling effects were high in both cohorts and in the worsened and unchanged groups (Table 5). These ceiling effects decreased in the post-fracture evaluation but were still beyond 15% in almost all of the groups.

The differences between baseline and follow-up BI were statistically significant. The change was always negative because all of the participants perceived less functionality and thus more dependency after the facture. In the worsened groups for both cohorts, the SES and SRM indexes were above the Cohen’s threshold of 0.20 for considering that a change has been found (SES: 1.81 for Cohort 1 and 0.93 for Cohort 2; SRM: 1.13 for Cohort 1 and 0.68 for Cohort 2). For the unchanged groups, although the differences between baseline and follow-up were also significant, these indexes were lower in both cohorts (SES: 0.41 for Cohort 1 and 0.11 for Cohort 2; SRM: 0.57 for Cohort 1 and 0.14 for Cohort 2), as expected.

Discussion

The BI is a very widely used questionnaire for the assessment of the functionality of the elderly and has been used in several conditions [6, 7].

Although the BI has been translated into Spanish [7], and there is some information on its psychometric properties [1], no papers have been found regarding its validation process. We employed this questionnaire in four different cohorts for the assessment of functionality in older adults in Spain, and we used these data to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the questionnaire.

Our results show that this version of the BI has good psychometric properties. It has good reliability, we have confirmed its structure via CFA, and it can discriminate between groups and detect differences between follow-up points.

The internal consistency complies with the standards [23]: the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was greater than 0.70, indicating that all the items are measuring the same concept. The internal consistency of the BI was also good in other psychometric analyses [31] or cultural validations [32]. Other reliability analyses could be evaluated in future studies to provide more evidence of this psychometric characteristic of the BI. In fact, a review published by Sainsbury et al. in 2005 stated that there is still a lack of data on test–retest reliability and inter-observer disagreement in chronic older people [6].

The results of the CFA supported the hypothesis of the unidimensionality of the BI, with good fit indexes, as other authors have also found [33]. Nevertheless, other researchers have identified two different factors [34]. Laake et al. [34] found differences in the number of factors depending on the type of patients who are studied. They proposed a two-factor structure in a group of patients with hip fracture, but in our study the factor analyses indicated a single-factor structure. It is possible that the different sample sizes (102 in the Laake et al. study and 1008 in ours) could have influenced the results of the factor analysis, resulting in different structures.

With regards to convergent and discriminant validity, almost all our hypotheses were confirmed. Although all of the correlations for convergent validity were statistically significant, some of them were weak, in accordance with those found in other studies [31, 33], and they were lower than the correlations observed by Cabañero-Martínez et al. [1]. Regarding discriminant validity, it has been difficult to identify other studies that evaluate this type of validity. Cabañero-Martínez et al. [1] did not find any discriminant analyses in their review of the Spanish versions of the BI.

The hypotheses for evaluating known-group validity were confirmed in all cases, although the differences in the BI baseline scores for gender were statistically significant only in one of the cohorts. In fact, some other researchers did not find differences in BI scores between men and women [26]. Other researchers did find differences in the BI scores for age [26] and comorbidities [27], showing that older people and those with more comorbidities had lower BI scores.

Finally, the responsiveness indexes found moderate to large changes in the worsened patients, indicating that the BI can detect differences between two follow-up points. Other studies have also evaluated the responsiveness of the BI by employing different indexes and have reported similar [6] or weaker results [35].

The strengths of our study include the comparison of the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the BI in four different cohorts. Despite the fact that the samples contain some differences, the results are similar, which gives confidence in the validity and reliability of the Spanish version of the BI. Another strength of this study is the large size of the samples, which complies with the minimum standards required for these types of analyses.

This study has also some limitations that must be addressed. First, these analyses were performed with four different cohorts obtained from different studies. This could introduce some bias because each study was performed under different conditions and with different patients. However, this limitation could be considered irrelevant because the psychometric results were similarly good in the four samples. Second, we evaluated the reliability of the questionnaire by means of the internal consistency with the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, but better evidence on the reliability should be added with a test–retest analysis. The third limitation is related to the missing data, which particularly affects the responsiveness results. We found some differences between the respondents and non-respondents in Cohort 1; thus, the responsiveness data should be interpreted with these facts in mind.

For future studies, we recommend performing some new type of analysis to increase the evidence of the reliability and validity of this version of the BI. In addition, other measurement properties could be analyzed according to the item response theory.

We have employed the BI in these cohorts mainly as a measure of functional status, but as frailty is a complex and multicomponent concept, where the new concept of cognitive frailty plays a crucial role [36, 37], future studies could explore the use of the BI as a measure of the association between physical and cognitive deterioration, not only in the field of an specific pathology, but also in studies of general health in the elderly.

Because the increasing age of the population is currently influencing the incidence of chronic conditions, it is essential to have access to reliable, valid, and easy-to-use instruments for the evaluation of the health status of patients. The Spanish version of the BI fulfills these characteristics because it has good psychometric properties; thus, it can be used in the evaluation of functionality and basic activities of daily living in elderly people with different conditions.

References

Cabañero-Martínez MJ, Cabrero-García J, Richart-Martínez M, Muñoz-Mendoza CL (2009) The Spanish versions of the Barthel Index (BI) and the Katz Index (KI) of activities of daily living (ADL): a structured review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 1:e77–e84

Millán-Calenti JC, Tubío J, Pita-Fernández S, González-Abraldes I, Lorenzo T, Fernández-Arruty T, Maseda A (2010) Prevalence of functional disability in activities of daily living (AdL), instrumental activities of daily living (IAdL) and associated factors, as predictors of morbidity and mortality. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 50:306–310

Torres Moreno B, Núñez González E, Pérez Hernández de G, Simón Turriate JP, Alastuey Giménez C, Díaz Melián J, Corujo Rodríguez E, González Bermúdez MD, Fernández Duque O (2009) Barthel and Charlson indexes for the prognosis of mortality and institutionalization in hospitalized geriatric patients. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 44:209–212

McDowell I, Newell C (1996). Measuring health. A guide to rating scales and questionnaires, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW (1965) Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J 14:61–65

Sainsbury A, Seebass G, Bansal A, Young JB (2005) Reliability of the Barthel Index when used with older people. Age Ageing 34:228–232

Baztán JJ, Pérez del Molin J, Alarcón T, San Cristóbal E, Izquierdo G, Manzarbeitia I (1993) Índice de Barthel: instrumento válido para la valoración funcional de pacientes con enfermedad cerebrovascular. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 28:32–40

González N, Aguirre U, Orive M, Zabala J, García-Gutiérrez S, Las Hayas C, Navarro G, Quintana JM (2014) Health-related quality of life and functionality in elderly men and women before and after a fall-related wrist fracture. Int J Clin Pract 68:919–928

Orive M, Aguirre U, García-Gutiérrez S, Las Hayas C, Bilbao A, González N, Zabala J, Navarro G, Quintana JM (2015) Changes in health-related quality of life and activities of daily living after hip fracture because of a fall in elderly patients: a prospective cohort study. Int J Clin Pract 69:491–500

León-Salas B, Ayala A, Blaya-Nováková V, Avila-Villanueva M, Rodríguez-Blázquez C, Rojo-Pérez F, Fernández-Mayoralas G, Martínez-Martín P, Forjaz MJ, Spanish Research Group on Quality of Life and Aging (2015) Quality of life across three groups of older adults differing in cognitive status and place of residence. Geriatr Gerontol Int 15:627–635

Pfeiffer E (1975) A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 23:433–441

Fernandez-Mayoralas G, Giraldez-Garcia C, Forjaz M J, Rojo-Perez F, Martinez-Martin P, Prieto-Flores ME, Spanish Research Group on Quality of Life and Aging (2012) Design, measures and sample characteristics of the CadeViMa-Spain survey on quality of life in community-dwelling older adults. Int Psychogeriatr 24:425–438

Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD (1996) A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary test of reliability and validity. Med Care 34:220–233

Lawton MP, Brody EM (1969) Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 9:179–186

Beaton DE, Wright JG, Katz JN (2005) Development of the QuickDASH: comparison of three item-reduction approaches. J Bone Jt Surg Am 87:1038–1046

Gummesson C, Ward MM, Atroshi I (2006) The shortened disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire (QuickDASH): validity and reliability based on responses within the full-length DASH. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 7:44

Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW (1988) Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol 15:1833–1840

Bilbao A, Quintana JM, Escobar A, Las Hayas C, Orive M (2011) Validation of a proposed WOMAC short form for patients with hip osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcome 9:75–85

EuroQol Group (1990) EuroQol: a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. The EuroQol Group. Health Policy 16:199–208

Martínez-Martín P, Fernández-Mayoralas G, Frades-Payo B, Rojo-Pérez F, Petidier R, Rodríguez-Rodríguez V, Forjaz MJ, Prieto-Flores ME, de Pedro Cuesta J (2009) Validation of the functional independence scale. Gac Sanit 23:49–54

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67:361–370

Broadhead WE, Gehlbach SH, de Gruy FV, Kaplan BH (1988) The Duke-UNC functional social support questionnaire: measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Med Care 26:709–723

Cronbach LJ (1951) Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of test. Psychometrika 16:297–334

Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH (1994) Psychometric theory, 3rd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Mulaik SA (1989) Evaluation of goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. Psychol Bull 105:430–445

Fontana C, Estany J, Pujol J, Segarra I, Jordán Y (2002) Concordancia entre índices de dependencia en las actividades de la vida diaria. Experiencia de aplicación en la población geriátrica de ámbito rural. Enferm Clin 12:47–53

Forjaz MJ, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Ayala A, Rodriguez-Rodriguez V, de Pedro-Cuesta J, Garcia-Gutierrez S, Prados-Torres A (2015) Chronic conditions, disability, and quality of life in older adults with multimorbidity in Spain. Eur J Intern Med 26:176–181

Wyrwich KW, Tierney WM, Wolinsky FD (1999) Further evidence supporting an SEM-based criterion for identifying meaningful intra-individual changes in health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol 52:861–873

Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D (1993) Cross-cultural adaptation of health- related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 46:1417–1432

Cohen J (1992) A power primer. Psychol Bull 112:155–159

Hsueh IP, Lin JH, Jeng JS, Hsieh CL (2002) Comparison of the psychometric characteristics of the functional independence measure, five item Barthel Index, and ten item Barthel Index in patients with stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 73:188–190

Galeoto G, Lauta A, Palumbo A, Castiglia SF, Mollica R, Santilli V, Sacchetti ML (2015) The Barthel Index: Italian translation, adaptation and validation. Int J Neurol Neurother 2:028

Moura JS, Amendola F, Martins MR, de Campos Oliveira MA (2010) Validation of the Barthel Index in elderly patients attended in outpatient clinics, in Brazil. Acta Paul de Enferm 23:218–223

Laake K, Laake P, Ranhoff AH, Sveen U, Wyller TB, Bautz-Holter E (1995) The Barthel ADL Index: factor structure depends on the category of patient. Age Aging 24:393–397

van Bennekom CA, Jelles F, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM (1996) Responsiveness of the rehabilitation activities profile and the Barthel Index. J Clin Epidemiol 49:39–44

Kelaiditi E, Cesari M, Canevelli M, van Kan GA, Ousset PJ, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Ritz P, Duveau F, Soto ME, Provencher V, Nourhashemi F, Salvà A, Robert P, Andrieu S, Rolland Y, Touchon J, Fitten JL, Vellas B, IANA, IAGG (2013) Cognitive frailty: rational and definition from an (IANA/IAGG) international consensus group. J Nutr Health Aging 17:726–734

Panza F, Seripa D, Solfrizzi V, Tortelli R, Greco A, Pilotto A, Logroscino G (2015) Targeting cognitive frailty: clinical and neurobiological roadmap for a single complex phenotype. J Alzheimer Dis 47:793–813

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support provided by the Biostatistics Research Group (Biostit), supported by the Department of Education, Linguistics Policy and Culture of the Basque Government (Ref: IT620-13). We gratefully thank the doctors of the Emergency Departments and all of the interviewers from the participating hospitals (Araba University Hospital (Santiago Hospital + Txagorritxu Hospital), Basurto University Hospital, and Cruces University Hospital), for their invaluable collaboration in patient recruitment. We are also grateful to the participants who voluntarily participated in this study and to the Research Committee of the Galdakao-Usansolo Hospital.

OFF (Older Falls Fracture)-IRYSS group: Jose María Quintana Lópeza,k,l, Susana García Gutiérreza,k,l, Carlota Las Hayas Rodríguezb,k,l, Jon Zabala Echenagusiac, Miren Orive Calzadaa,k,l, Nerea González Hernándeza,k,l, Urko Aguirre Larracoecheaa,k,l, Ane Anton Ladislaoa,k,l, Iratxe Lafuente Guerrero a,k,l, Amaia Bilbao Gonzálezd,k,l, Luis Angel Sanado Lampreavee, Ignacio Javier Gamilla Iglesiase, Elena Urrutia Sanzberroe, Rocío Fernández Albae, Ana Iribas Garnicae, Elena Urrutia Sanze, Juan Carlos Arenaza Merinof, Lander Larrea Azkorrag, Celestino Gómez Calatravah, Francisco Rivasi, Gemma Navarro Rubioj.

aUnidad de investigación. Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo. Galdakao (Bizkaia); bDepartamento de Personalidad, evaluación y tratamiento. Universidad de Deusto. Bilbao (Bizkaia); cServicio de traumatología. Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo. Galdakao (Bizkaia), Universidad del País Vasco (UPV). Leioa (Bizkaia); dUnidad de investigación. Hospital Universitario Basurto. Basurto (Bizkaia); eServicio de traumatología. Hospital Universitario Araba. Vitoria-Gasteiz (Araba); fServicio de traumatología. Hospital Universitario Basurto (Bizkaia); gServicio de traumatología. Hospital Universitario Cruces. Barakaldo (Bizkaia); hServicio de traumatología. Hospital Universitario Donostia. San Sebastián-Donostia (Gipuzkoa); iUnidad de epidemiología. Hospital Costa del Sol. Marbella (Málaga); jUnidad de epidemiología. Corporació Parc Tauli Clinic. Sabadell (Barcelona); kRed de Investigación en Servicios de Salud en Enfermedades Crónicas-REDISSEC; lCentro de investigación en Cronicidad (Kronikgune). Bilbao (Bizkaia).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All of the authors contributed to the critical revision of the paper and approved the final version. Nerea González drafted the manuscript and incorporated the revisions of coauthors. Amaia Bilbao conducted the statistical analysis. Miren Orive and Carlota Las Hayas enrolled the participants. Susana García-Gutiérrez, Jose M. Quintana, Joao Forjaz, and Alba Ayala contributed to the design of the study and helped interpret the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by a grants from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (PI08/90417); Department of Health of the Basque Country (2008111016); Asociación para la promoción de la Investigación clínica del Hospital de Galdakao-GOSIKER (BIOEF11/033); KRONIKGUNE- Centro de Investigación en Cronicidad (KRONIK 11/005); and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

This study was approved by the Ethics Committees and/or Review Boards of the participating institutions and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

González, N., Bilbao, A., Forjaz, M.J. et al. Psychometric characteristics of the Spanish version of the Barthel Index. Aging Clin Exp Res 30, 489–497 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-017-0809-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-017-0809-5