Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to comprehensively and thoroughly examine the psychometric properties of two commonly used weight-related self-stigma instruments on Iranian adolescents with overweight or obesity: Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire [WSSQ] and Weight Bias Internalization Scale [WBIS].

Methods

After ensuring the linguistic validity of both the WSSQ and WBIS in their Persian versions, 737 Iranian adolescents with overweight or obesity (male = 354; mean age = 15.8 ± 1.3 years; body mass index = 30.0 ± 4.8 kg/m2) completed both questionnaires and other relevant measures regarding their depression, anxiety, stress, dietary self-efficacy, weight efficacy lifestyle, quality of life, body fat, self-esteem, body shape preoccupation, and sleepiness.

Results

In the scale level, the confirmatory factory analysis verified the two-factor structure for the WSSQ and the single-factor structure for the WBIS. The factorial structures were further found to be invariant across gender (male vs. female) and across weight status (overweight vs. obesity). Additionally, both the WSSQ and WBIS had promising properties in internal consistency, test–retest reliability, separation reliability, and separation index. In the item level, all items but WBIS item 1 (infit mean square = 1.68; outfit mean square = 1.60) had satisfactory properties in factor loadings, corrected item-total correlation, test–retest reliability, and infit and outfit mean square. Moreover, all the items did not display substantial differential item functioning (DIF) across gender and across weight status.

Conclusion

Both the WSSQ and WBIS were valid instruments to assess the internalization of weight bias for Iranian adolescents with overweight or obesity.

Level of evidence

Level V, cross-sectional descriptive study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The impact of overweight and obesity on humans has been widely studied in different aspects, including physiological, social, and psychological health [1,2,3]. Internalized stigma from weight (or weight-related self-stigma) is suggested to be one of the key factors for the impaired social and psychological health conditions caused by overweight or obesity [4, 5]. Specifically, weight-related self-stigma is a process of self-devaluation for people who internalize the negative evaluation of their weight regardless of their weight status [5,6,7]. That is, after an individual believes that a person with overweight is worthless and inferior to people with healthy weight, the individual endorses this negative concepts to himself or herself. Through this process, people who have weight-related self-stigma are suggested to have self-prejudice and self-discrimination reactions [5, 6, 8]. As a result, higher weight-related self-stigma was associated with the following outcomes: being teased and bullied, increased anxiety and depression, and decreased physical activity [5, 7, 9]. Given that the interest in studying social health and behavior is growing [10], a deep investigation into weight-related self-stigma is highly recommended.

Unfortunately, there are no validated tools available to measure weight-related self-stigma for Persian-speaking populations, and a literature gap exists in this large population (~ 110 million people are native Persian speakers across Iran, Pakistan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan) [11]. Furthermore, the childhood overweight/obesity rate in one Persian-speaking country, Iran, is high (~ 15%) [12]. Hence, the first step in studying weight-related self-stigma in this population is to examine the psychometric properties of the existing tools. Although our study only recruited Persian-speaking adolescents from a single city (Qazvin), we consider that future studies of Persian-speaking people can benefit from our results, because they will have an initial idea of how the weight-related self-stigma tools perform in relevant populations; however, such future studies still need to verify whether our translated tools are reliable and valid in their studied populations.

Two widely used instruments—the Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire (WSSQ) [13] and the Weight Bias Internalization Scale (WBIS) [14]—were found to have satisfactory reliability and validity mostly in Western and European populations. Specifically, the psychometric properties of the WSSQ have been verified in the following: American adults [13], French adolescents [15], German adults with severe obesity [16] and those undergoing bariatric surgery [17], Portuguese women with overweight or obesity [18], and Turkish adults with severe obesity [19]. The psychometric properties of WBIS have been studied in American adults [14, 20] and adolescents [21]; German adults with obesity [22], those undergoing bariatric surgery [17], and children [23], Turkish adults [24, 25], and Italian adults with obesity [26]. Also, a recent study on Hong Kong children demonstrated that both WSSQ and WBIS have satisfactory psychometric properties [27]. As a result, we believe that validating both the WSSQ and WBIS in their Persian versions will benefit healthcare providers in taking care of weight-related self-stigma issues for Persian-speaking populations. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have applied a modern test theory such as the Rasch model to examine the psychometric properties of the Persian WSSQ and WBIS. Because the Rasch analysis provided different information from psychometric testing in the classical test theory (e.g., factor analysis and internal consistency), we proposed to examine the Persian WSSQ and WBIS simultaneously using the classical test theory and Rasch model to accumulate the scientific evidence for both instruments. Thus, healthcare providers may have a comprehensive and thorough understanding of the psychometric properties of both instruments and subsequently use them appropriately. Specifically, in addition to the psychometric information derived from the classical test theory, the Rasch model can provide the following information: (1) the item validity can be individually analyzed and the information of whether the item is redundant can be observed, (2) the item difficulty can be calculated using mathematical estimations on probability, (3) the item score rated by ordinal scale can be converted into an interval scale with a universal unit (i.e., logit) [28,29,30].

Additionally, the current literature does not have measurement invariance information of both the WSSQ and WBIS. Measurement invariance is an assumption for studies to compare different subgroups in the same instrument: when different subgroups interpret the studied instrument similarly, the comparisons between the subgroups in their instrument score are meaningful [31]. In contrast, if the measurement invariance is not supported, the comparisons between different subgroups are meaningless. Thus, the current practice is to establish the measurement invariance before comparing instrument scores in subgroups [32, 33]. Given the lack of measurement invariance information for the WSSQ and WBIS, comparing WSSQ or WBIS scores across genders or weight status groups may be invalid.

The main objective of this study was to examine the psychometric properties of the Persian WSSQ and WBIS among Iranian adolescents with overweight or obesity. First, both the WSSQ and WBIS were translated into Persian and then their validity and reliability were examined using both the classical test theory and Rasch model. Second, the differential item functioning (DIF) in the item level and measurement invariance in the scale level were examined for both the instruments. Finally, the concurrent validity of both WSSQ and WBIS total scores was investigated with a series of external criteria: depression, anxiety, stress, dietary self-efficacy, weight efficacy lifestyle, quality of life, body composition of fat, self-esteem, body shape preoccupation, and sleepiness. Several hypotheses were made according to the objectives and the literature: (1) the Persian WSSQ has acceptable internal consistency [14, 15], test–retest reliability [18], and a confirmed two-factor structure [15]; (2) the Persian WBIS has acceptable internal consistency [13], test–retest reliability [26], and a confirmed one-factor structure [13, 22]; and (3) the Persian WSSQ and WBIS were associated with psychosocial [5, 16] and weight-related outcomes [22, 34].

Methods

Participants and process

Between September 2017 and May 2018, 40 high schools were randomly selected from 150 schools in Qazvin, the largest city and capital in the Qazvin Province, Iran. The population of Qazvin is 1.27 million with a density of 9030 people per square kilometer. Qazvin is 165 km northwest of Iran’s capital (Tehran) and has cultural characteristics and socioeconomic status similar to Tehran. Qazvin has 150 high schools according to the Organization for Education at Qazvin [35]. We first obtained the list of the 150 high schools and recruited our participants using a two-stage clustered sampling technique. Specifically, 20 high schools were randomly selected from the list provided by the Organization for Education, then 2 classes were selected randomly from the selected schools. Students in the selected classes were all invited to participate in this study.

All the adolescents in the selected schools received physical examinations using standard equipment. The inclusion criteria for the participants were as follows: (1) overweight or obese (i.e., BMI ≥ 85th percentile for specific age and gender [36]), (2) ages between 13 and 18 years, and (3) able to speak Persian. The exclusion criteria were (1) having chronic diseases such as mental health problems, including eating disorders and learning disabilities; (2) unwilling to participate; and (3) failing to return parental consent forms.

Among the 1010 adolescents we approached, 190 were not eligible because 151 were not overweight and 39 were over 19 years of age, 4 were excluded due to mental health problems, and 79 declined to participate. Thus, the response rate was near 73%. The rest of the participants (n = 737) voluntarily participated in this study and written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their guardians before the survey. All measures were administered by three trained research associates in the class setting; 14 days later, all the measures were administered again for all the participants.

Apart from the assessments of the adolescents, we collected demographic information of their parents’ BMI and educational levels. We obtained the information during monthly meetings with the schools’ principals in which all parents participated. However, 59 parents did not attend the meeting and we contacted them by phone to arrange an in-person meeting individually at their convenience to collect information. Because parents’ lifestyles and educational levels are important factors in their children’s weight status [37], we believe that parents’ BMI and educational year are relevant information in the present study. The Ethics Committee of the Qazvin University of Medical Sciences approved the study.

Translation procedure

The translation procedure was performed in several steps based on the international guidelines [38]. First, two bilingual translators who were native Persian speakers independently translated the WSSQ and WBIS from English to Persian. The translated versions were then synthesized as an interim Persian version by the translators and the last author. The interim Persian version was then translated back into English by two native English speakers. The back translators were not aware of the original English versions of these questionnaires. An expert committee (including a pediatrician, psychologist, sociologist, endocrinologist, and a pediatric nurse) was convened to achieve cross-cultural equivalency for both scales. The expert committee reviewed all forward and backward translated versions and consolidated all versions to develop prefinal versions. The prefinal versions of the WSSQ and WBIS were then piloted on 43 overweight and obese adolescents (mean age 15.2 ± 2.4; 24 girls) to ensure that the language equivalency and the final Persian versions of the WSSQ and WBIS were generated. During the translation process, no major problems occurred and only one minor change in the wording was performed. Specifically, we simplified the word “insecure” to “uncertain” to make the sentence (Item 7 in the WSSQ “I feel insecure about others’ opinions of me”) more understandable in Persian language.

Measures

Anthropometrics

We measured all the participants’ and their parents’ heights using a stadiometer (Seca Model 207, Seca, Hamburg, Germany) to the nearest 0.1 cm after removing their shoes, and measured their weights using a calibrated digital scale to the nearest 0.1 kg. Body mass index (BMI) was then calculated by dividing body weight by squared height in meters with a Z score of BMI determined afterwards [39]. Through age and gender-specific norms from the Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, a participant with a BMI at 85–95 percentile was defined as overweight; a participant with a BMI at 95 percentile or higher was defined as obese [36]. We also measured all the participants’ body fat percentage using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA). We measured both BMI and BIA, because BMI is the gold standard with a specific cutoff for us to classify the weight status of an adolescent, while BIA has less bias than BMI to quantify an individual’s excess weight (e.g., athletes may have high BMI but low fat).

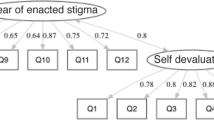

Weight self-stigma questionnaire

The WSSQ was found to have two domains (self-devaluation sample item: “People think that I am to blame for my weight problems.” and fear of enacted sample item: “I caused my weight problems.”). Each domain contained six items rated on a five-point Likert Scale. The English WSSQ has satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.81 and 0.87), and a higher score indicates a higher level of weight-related self-stigma [13]. The WSSQ also had satisfactory internal consistency (ω = 0.91 and 0.93) in adolescent populations [15].

Weight bias internalization scale

The WBIS was found to be unidimensional using 11 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (sample item: “I hate myself for being overweight”). The English WBIS has satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.90), and a higher score indicates a higher level of weight-related self-stigma [14]. The WBIS also had satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.92) in adolescent populations [21].

Depression, anxiety, and stress scale (DASS-21)

The DASS-21 includes three subscales—depression, anxiety, and stress—and each subscale contained seven items rated on a four-point Likert scale. A higher score in DASS-21 indicates a higher level of depression, anxiety, or stress [40]. The Persian DASS-21 demonstrates satisfactory psychometric properties, including excellent internal consistency (α = 0.84–0.91) [41, 42] and acceptable concurrent validity (r = 0.4–0.7 with the Four Systems Anxiety Questionnaire and Beck Depression Inventory) [41]. The DASS-21 also had satisfactory internal consistency in the adolescent population (α = 0.79–0.87) [43] and in the present study (α = 0.80–0.85).

Child dietary self-efficacy scale (CDSS)

The CDSS contains 15 items with a 3-point Likert Scale to assess whether a child has self-efficacy in choosing healthy and low-fat food instead of unhealthy and high-fat food [44]. The Persian CDSS has been translated using standard procedures earlier [45] but without psychometric testing. A higher score in CDSS indicates a higher level of self-efficacy in choosing healthy food, and the CDSS has satisfactory psychometric properties, including excellent internal consistency (α = 0.84) and supported criterion-related validity [44]. The CDSS also had satisfactory internal consistency in the present study (α = 0.79).

Weight efficacy lifestyle (WEL)

The WEL contains 20 items to assess whether a child has self-efficacy of regime behavior using a 5-point Likert scale. A higher score in WEL indicates a higher level of self-efficacy [46]. The Persian WEL has promising psychometric properties, including satisfactory internal consistency in its total score (α = 0.88) [47]. The WEL also had satisfactory internal consistency in adolescent populations (α = 0.83) [48] and in the present study (α = 0.88).

Pediatric quality of life (PedsQL)

The PedsQL is one of the commonly used instruments to assess children’s quality of life [49]. We used the brief version of the PedsQL (15 items), and rated all the items on a five-point Likert Scale; a higher score indicated a better quality of life [50]. The Persian PedsQL has promising psychometric properties, including satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.82) and supported known-group validity [51]. The PedsQL also had satisfactory internal consistency in the present study (α = 0.77).

Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA)

The BIA measures an individual’s body fat. The BIA was carried out using with the Tanita TBF-531 bioelectrical impedance analyzer (Tanita UK Ltd., Middlesex, UK). The adolescents were asked to fast overnight and to void their bladder before starting the examination. The BIA measurements were carried out by a trained researcher according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES)

The RSES contains ten items to assess self-esteem using a five-point Likert Scale. A higher score in RSES indicates a higher level of self-efficacy [10]. The Persian RSES has promising psychometric properties, including verified one-factor structure [52]. The RSES also had satisfactory internal consistency in adolescent populations (α = 0.71) [53] and in the present study (α = 0.90).

Body shape questionnaire C8 (BSQ-C8)

The BSQ-C8 contains eight items and is a short version of the body shape questionnaire that assesses body shape preoccupation. All the items are rated on a six-point Likert scale, and a higher score of BSQ-C8 indicates higher levels of dissatisfaction in body shape [54]. The Persian BSQ-C8 has promising psychometric properties, including acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.79) and supported concurrent validity [55]. The BSQ-C8 also had satisfactory internal consistency in adolescent populations (α = 0.96) [56] and in the present study (α = 0.86).

Epworth sleepiness scale for children and adolescents (ESS-CHAD)

The ESS-CHAD contains eight items to assess the performance of daytime sleepiness for children and adolescents. All the items are rated on a four-point Likert scale, and a higher score indicated greater sleepiness [57]. The Persian ESS-CHAD has promising psychometric properties, including satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.79) and verified construct validity in confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) [58]. The ESS-CHAD also had satisfactory internal consistency in the present study (α = 0.83).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics, internal consistency, and test–retest reliability

We used mean with SD for continuous data and frequency with percentage for categorical data to describe participants’ characteristics. For internal consistency, ordinal α (expected cutoff > 0.7) together with corrected item-total correlation (expected cutoff > 0.4) were calculated [59]. For test–retest reliability in a 14-day interval, correlation coefficients higher than 0.4 were expected. We also calculated the ceiling and floor effects (i.e., what proportion of the participants had the lowest or highest score in each instrument), a value less than 20% was recommended [32].

Confirmatory factor analysis and measurement invariance

CFA was further used to examine the two-factor structure for the WSSQ and single-factor structure for the WBIS. We used a polychoric correlation matrix with robust estimator (i.e., weighted least square mean and variance adjusted estimator) in the CFA. In addition to the factor loadings (expected cutoff > 0.4) [59], we used several cutoffs to determine the acceptable properties: a nonsignificant χ2 test, a comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.9, a Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) > 0.9, a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08, and a standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) < 0.08 [60]. Moreover, we expected to have average variance extracted higher than 0.5 and composite reliability higher than 0.6 [60].

The two-factor structure of the WSSQ and single-factor structure of the WBIS were then tested for their measurement invariance using three nested CFA models (aka multigroup CFA; MGCFA) across gender (males vs. females) and weight status (overweight vs. obesity). The baseline model was a configural model that treated WSSQ as a two-factor structure and WBIS as a single-factor structure. The second model constrained males and females (or adolescents with overweight and those with obesity) who had equal factor loadings in the factorial structures. The third model constrained males and females (or adolescents with overweight and those with obesity) having equal factor loadings and equal item intercepts in the factorial structures. In addition to a nonsignificant χ2 difference test, ∆CFI, ∆SRMR, and ∆RMSEA were together used to examine whether measurement invariance was supported. If ∆CFI, ∆SRMR, and ∆RMSEA were all less than 0.01, the measurement invariance was supported for the tested factorial structure [31].

Rasch analysis and differential item functioning (DIF)

Because Rasch analysis tests the unidimensional measure, the WSSQ was tested by its domain instead of the entire scale in the Rasch model, because the WSSQ was found to be a two-factor structure [13]. The WBIS was tested using the entire scale, because it was found to be unidimensional [14]. The Rasch analysis reported the item difficulty using the probability with an additive unit logit. For example, an item with an item difficulty at 0.5 logit indicated that on average the participants had a 50% chance to select the middle answer (score 3 in the 5-point scale) in a Likert-type scale. We also examined each item using infit mean square (MnSq) and outfit MnSq to determine whether it contributed to the underlying concepts of weight-related self-stigma: both infit and outfit MnSq range between 0.5 and 1.5 are in anticipation [61].

Because the psychometric results calculated using the Rasch models were not influenced by the sample characteristics, the separation reliability and index (including item separation reliability, person separation reliability, item separation index, and person separation index) were computed for separation reliability (expected cutoff > 0.7) and separation index (expected cutoff > 2). Moreover, DIF was used to examine whether different genders or adolescents in different weight status interpreted the item description similarly, where a DIF contrast greater than 0.5 was substantial and may have been problematic in usage [62].

Concurrent validity using multiple linear regression models

After ensuring the invariant factorial structures of WSSQ and WBIS, we investigated the concurrent validity of both instruments using regression models. Specifically, the WSSQ domain scores and the WBIS total scores were treated as independent variables separately in each regression model (i.e., WSSQ domain scores and WBIS total scores were not constructed in the same regression model); age and gender were treated as control variables for all the regression models. We used the following standard criteria as dependent variables in each regression model: depression, anxiety, stress, child dietary self-efficacy, weight efficacy lifestyle, quality of life, BIA, self-esteem, body shape preoccupation, and sleepiness. Thus, 33 regression models were constructed (11 dependent variables × 3 independent variables [two WSSQ domains and a WBIS entire scale]).

Missing data in the sample were treated using pairwise deletion, although the percentage of missing data was trivial (2.6%). Additionally, Little’s missing completely at random (MCAR) test (df = 452, χ2 = 482.479, p = 0.155) was nonsignificant, which supported the use of pairwise deletion: it is unbiased when data are missing completely at random [63].

Softwares used in this study were Mplus 7 for CFA and measurement invariance, WINSTEP 4.1.0 for Rasch analysis and DIF, and SPSS 24.0 for the rest of the analyses.

Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the participants (N = 737; nmale = 354 [48.0%]), including the mean age (15.8 ± 1.3 years), BMI (30.0 ± 4.8 kg/m2), z-BMI score (2.6 ± 1.1), and scores assessed from different questionnaires.

The psychometric properties were satisfactory for all the WSSQ item scores (factor loadings = 0.51–0.84; corrected item-total correlation = 0.68–0.79; test–retest reliability = 0.71–0.92 [except for WSSQ item 1 with a value of 0.63]; infit MnSq = 0.75 to 1.33; outfit MnSq = 0.71–1.31; DIF = − 0.41–0.40 across gender; DIF = − 0.16–0.26 across weight status) and all the WBIS item scores (factor loadings = 0.47–0.79; corrected item-total correlation = 0.44–0.71; test–retest reliability = 0.71–0.84; infit MnSq = 0.68–1.14; outfit MnSq = 0.78–1.17; DIF = − 0.33–0.45 across gender; DIF = − 0.31–0.25 across weight status), except for WBIS item 1 (infit MnSq = 1.68 and outfit MnSq = 1.60; Table 2). Because WBIS item 1 was misfit according to its infit and outfit MnSq, WBIS item 1 may not be relevant in assessing weight-related self-stigma.

In terms of the scale level, the WSSQ domain scores and WBIS total score demonstrated acceptable ceiling and floor effects (0.4–10.0%); satisfactory internal consistency (ordinal α = 0.87–0.91); test–retest reliability (r = 0.73–0.78). Moreover, all the CFA fit indices indicated acceptable fitness of the two-factor WSSQ structure (CFI = 0.971, TLI = 0.963, RMSEA = 0.056, and SRMR = 0.027) and the one-factor WBIS structure (CFI = 0.932, TLI = 0.914, RMSEA = 0.070, and SRMR = 0.046). Average variance extracted and composite reliability calculated using the CFA findings were both satisfactory for the WSSQ domain scores and the WBIS total score (Table 3). Moreover, the separation reliability and index computed from Rasch model were excellent in both the WSSQ domain scores and WBIS total score (Table 3).

Measurement invariance was then conducted to evaluate whether the structures of WSSQ and WBIS were invariant across gender and weight status (Table 4). The nested CFA models showed that the factor loading constrained models were not significantly different from the configural models (∆χ2 = 15.04 [p = 0.131] and 15.35 [p = 0.120] for WSSQ; 10.49 [p = 0.399] and 10.73 [0.379] for WBIS); the factor loading and item intercept constrained models were not significantly different from the factor loading constrained models (∆χ2 = 11.00 [p = 0.358] and 9.23 [p = 0.510] for WSSQ; 14.80 [p = 0.140] and 7.42 [p = 0.685] for WBIS). Additionally, other fit indices on assessing measurement invariance all supported that the WSSQ and WBIS structures were invariant across gender and weight status.

After ensuring the invariant factorial structures of WSSQ and WBIS, concurrent validity further illustrated that both WSSQ and WBIS had sound psychometric properties. Both WSSQ domain scores and WBIS total scores were significantly associated with most of the relevant standards, including depression, anxiety, stress, child dietary self-efficacy, weight efficacy lifestyle, quality of life, BIA, body shape preoccupation, and sleepiness (Table 5).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has applied both classical tests (e.g., CFA) and modern test theories (i.e., Rasch models) to examine the psychometric characteristics of the WSSQ and WBIS among adolescents with overweight and obesity. Similar to previous findings, our study showed that the WSSQ had a two-factor structure [15, 64] and that the WBIS had a single-factor structure [22, 23]. Furthermore, the results of the study extend to the evidence on factorial invariance across gender and weight status groups among adolescents. In addition, both WSSQ and WBIS measures were associated with other measures related to psychological health (including depression, anxiety, stress, dietary self-efficacy, weight efficacy, quality of life, and body shape preoccupation), body composition (fat percentage), and reaction behaviors (sleepiness). However, given that our findings were from a single study, the generalizability of our psychometric findings is restricted.

Other psychometric findings derived from the classical test theory were in accordance with almost all the previous findings [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Specifically, all the findings agreed that both WSSQ and WBIS had acceptable to excellent internal consistency demonstrated by Cronbach’s α. Some of the studies demonstrated the satisfactory test–retest reliably for WSSQ [13] and WBIS [24] in scale level. Our test–retest findings extended the satisfactory properties from scale level to item level.

Although our Rasch findings are almost in line with our classical test theory findings and pervious research findings [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26], WBIS item 1 (No matter how much I weigh, I can do just as much as everyone else) was found to have some psychometric problems. Specifically, relatively high infit and outfit MnSq were observed. Thus, the WBIS item 1 was not embedded in the weight-related self-stigma concept. The out-of-concept problem in WBIS item 1 has been illustrated in other studies on children [23], adolescents [21], and adults [14, 20, 22]. Moreover, these studies showed that the psychometric performance of the entire WBIS was improved after removing item 1. Because item 1 has a different direction (higher score indicates less stigma) from other items (higher score indicates more stigma), the wording effect may have contributed to its poor psychometric performance [65].

From our findings, both WSSQ and WBIS are sound tools to assess weight-related self-stigma; however, based on our results, there are different circumstances that are preferable in using one than using the other. Specifically, if a study aims to use a universal score for weight-related self-stigma, the WBIS is preferable because of its supported one-factor structure. In contrast, WSSQ may be used to detect the different subconcepts of weight-related self-stigma. Additionally, the WSSQ domain scores had a stronger relationship with the DASS domain scores than did the WBIS total score; therefore, futures studies examining the effects of weight-related self-stigma on psychological distress may consider using WSSQ rather than WBIS. In contrast, the WBIS total score had a stronger relationship with WEL total score, BIA and BSQ-C8 total score than did the WSSQ domain scores; therefore, future studies examining the association between weight-related self-stigma and weight-related outcomes may want to use WBIS rather than WSSQ.

Our study has the following strengths. First, we applied comprehensive psychometric testing in a large sample of Iranian adolescents with overweight (N = 737). Although all the participants were recruited in a single city, we used two-stage randomized clustered sampling to ensure the representativeness of our sample in this city (Qazvin). Our comprehensive psychometric testing especially provides additional information from Rasch models to add to the current literature. Given that our study is the first to use Rasch model to test the psychometric properties of WSSQ and WBIS, future research is recommended to use the same approach to corroborate our psychometric findings. Second, we used a series of external criteria to demonstrate the different uses of WSSQ and WBIS. With the findings about the relationship between external criteria and WSSQ/WBIS, clinical implications of when to use WSSQ and when to use WBIS were discussed above.

There are some limitations in this study. First, we did not recruit adolescents who were of normal weight or underweight in this study. Therefore, our psychometric findings may not be generalizable to adolescents who are not overweight. Given that prior findings indicated that people who are not overweight or obese are also likely to suffer from weight-related self-stigma [5, 66, 67], future studies are needed to investigate whether the Persian WSSQ and WBIS can be used for people who have the correct weight. Second, the Persian CDSS used in this study does not have evidence about its psychometric properties. Therefore, the concurrent validity of WSSQ and WBIS supported by the association with CDSS is somewhat unstable. Specifically, the Persian CDSS score may not be reliable in our study because of the lack of evidence about its psychometric properties in the literature [68]. However, given that all other criteria support the concurrent validity, we believe that this is not a serious flaw in this study. Third, as our findings were from a single city in Iran, the generalizability of our finding to the entire Persian-speaking population needs further evidence for support. Specifically, future psychometric studies that use our translated Persian WSSQ and WBIS on different Persian-speaking populations are strongly recommended. Finally, adolescents with mental health problems were excluded from this study. Therefore, our findings may not reflect the true conditions of those having high levels of weight-related self-stigma, because adolescents with high levels of weight-related self-stigma are also likely to have mental health problems.

In conclusion, our results indicate that both the Persian WSSQ and WBIS are valid instruments to assess the internalization of weight bias in a sample of Iranian adolescents with overweight or obesity. Specifically, factorial structures of both instruments were verified and the structures were invariant across gender and across weight status (overweight vs. obesity) in different types of psychometric theory (classical and modern test theories). However, special attention should be paid to item 1 in the WBIS, because it had unsatisfactory fit statistics in the Rasch model. Nevertheless, our findings support the use of both the WSSQ and WBIS in treatment programs on reducing weight-related self-stigma, such as the Weight Bias Internalization and Stigma (BIAS) program [34].

References

Harriger JA, Thompson JK (2012) Psychological consequences of obesity: weight bias and body image in overweight and obese youth. Int Rev Psychiatry 24(3):247–253. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2012.678817

Lee CT, Lin CY, Strong C, Lin YF, Chou YY, Tsai MC (2018) Metabolic correlates of health-related quality of life among overweight and obese adolescents. BMC Pediatr 18(1):25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1044-8

Ratcliffe D, Ellison N (2015) Obesity and internalized weight stigma: a formulation model for an emerging psychological problem. Behav Cogn Psychother 43(2):239–252. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465813000763

Cheng MY, Wang SM, Lam YY, Luk HT, Man YC, Lin CY (2018) The relationships between weight bias, perceived weight stigma, eating behavior and psychological distress among undergraduate students in Hong Kong. J Nerv Ment Dis 206(9):705–710. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000869

Wong PC, Hsieh YP, Ng HH, Kong SF, Chan KL, Au TYA, Lin CY, Fung XCC (2018) Investigating the self-stigma and quality of life for overweight/obese children in Hong Kong: a preliminary study. Child Ind Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9573-0

Hilbert A, Braehler E, Haeuser W, Zenger M (2014) Weight bias internalization, core self-evaluation, and health in overweight and obese persons. Obesity 22(1):79–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20561

Cheng OY, Yam CLY, Cheung NS, Lee PLP, Ngai MC, Lin CY (2019) Extended Theory of Planned Behavior on eating and physical activity. Am J Health Behav 43(3):569–581

Lin CY (2019) Ethical issues of monitoring children’s weight status in school settings. Soc Health Behav 2(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/SHB.SHB_45_18

Lin YC, Latner JD, Fung XCC, Lin CY (2018) Poor health and experiences of being bullied in adolescents: self-perceived overweight and frustration with appearance matter. Obesity 26(2):397–404. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22041

Pakpour AH, Lin CY, Alimoradi Z (2018) Social health and behavior needs more opportunity to be discussed. Soc Health Behav 1(1):1. https://doi.org/10.4103/SHB.SHB_20_18

Rashidvash V (2013) Iranian people: Iranian Ethnic Groups. Int J Hum Soc Sci 3(15):216–226

Mottaghi A, Mirmiran P, Pourvali K, Tahmasbpour Z, Azizi F (2017) Incidence and prevalence of childhood obesity in Tehran, Iran in 2011. Iran J Public Health 46(10):1395–1403

Lillis J, Luoma JB, Levin ME, Hayes SC (2010) Measuring weight self-stigma: the Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire. Obesity 18(5):971–976. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2009.353

Durso LE, Latner JD (2008) Understanding self-directed stigma: development of the Weight Bias Internalization Scale. Obesity 16(Suppl. 2):S80–S86. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.448

Maïano C, Aimé A, Lepage G, Team ASPQ, Morin AJS (2017) Psychometric properties of the Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire (WSSQ) among a sample of overweight/obese French-speaking adolescents. Eat Weight Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0382-0

Hain B, Langer L, Hünnemeyer K, Rudofsky G, Zech U, Wild B (2015) Translation and validation of the German version of the Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire (WSSQ). Obes Surg 25(4):750–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-015-1598-6

Hübner C, Schmidt R, Selle J, Köhler H, Müller A, de Zwaan M, Hilbert A (2016) Comparing self-report measures of internalized weight stigma: the Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire versus the Weight Bias Internalization Scale. PLoS One 11(10):e0165566. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165566

Palmeira L, Cunha M, Pinto-Gouveia J (2018) The weight of weight self-stigma in unhealthy eating behaviours: the mediator role of weight-related experiential avoidance. Eat Weight Disord 23(6):785–796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0540-z

Sevincer GM, Kaya A, Bozkurt S, Akin E, Kose S (2017) Reliability, validity, and factorial structure of the Turkish version of the Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire (Turkish WSSQ). Psychiat Clin Psych 27(4):386–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750573.2017.1379717

Lee MS, Dedrick RF (2016) Weight Bias Internalization Scale: psychometric properties using alternative weight status classification approaches. Body Image 17:25–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.01.008

Roberto CA, Sysko R, Bush J, Pearl R, Puhl RM, Schvey NA, Dovidio JF (2012) Clinical correlates of the Weight Bias Internalization Scale in a sample of obese adolescents seeking bariatric surgery. Obesity 20(3):533–539. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2011.123

Hilbert A, Baldofski S, Zenger M, Löwe B, Kersting A, Braehler E (2014) Weight Bias Internalization Scale: psychometric properties and population norms. PLoS One 9(1):e86303. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086303

Zuba A, Warschburger P (2018) Weight bias internalization across weight categories among school-aged children. Validation of the Weight Bias Internalization Scale for Children. Body Image 25:56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.02.008

Apay SE, Yilmaz E, Aksoy M, Akalın H (2017) Validity and reliability study of Modified Weight Bias Internalization Scale in Turkish. Int J Caring Sci 10(3):1341–1347

Erdogan Z, Kurcer MK, Kurtuncu M, Catalcam S (2018) Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the weight Self-stigma questionnaire. J Pak Med Assoc 68(12):1798–1803

Innamorati M, Imperatori C, Lamis DA, Contardi A, Castelnuovo G, Tamburello S, Manzoni GM, Fabbricatore M (2017) Weight bias internalization scale discriminates obese and overweight patients with different severity levels of depression: the Italian Version of the WBIS. Curr Psychol 36(2):242–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9406-6

Pakpour AH, Tsai M-C, Lin Y-C, Strong C, Latner JD, Fung XCC, Lin C-Y, Tsang HWH (2019) Psychometric properties and measurement invariance of the Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire and Weight Bias Internalization Scale in Hongkongese children and adolescents. Int J Clin Health Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2019.03.001

Boone WJ (2016) Rasch analysis for instrument development: why, when, and hHow? CBE Life Sci Educ 15(4):rm4. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-04-0148

Chang CC, Su JA, Tsai CS, Yen CF, Liu JH, Lin CY (2015) Rasch analysis suggested three unidimensional domains for Affiliate Stigma Scale: additional psychometric evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol 68(6):674–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.01.018

Tractenberg RE (2010) Classical and modern measurement theories, patient reports, and clinical outcomes. Contemp Clin Trials 31(1):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1551-7144(09)00212-2

Cheung GW, Rensvold RB (2002) Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct Eq Mod 9(2):233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Chang CC, Su JA, Chang KC, Lin CY, Koschorke M, Thornicroft G (2018) Perceived stigma of caregivers: psychometric evaluation for Devaluation of Consumer Families Scale. Int J Clin Health Psychol 18(2):170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2017.12.003

Lin CY, Strong C, Latner JD, Lin YC, Tsai MC, Cheung P (2019) Mediated effects of eating disturbances in the association of perceived weight stigma and emotional distress. Eat Weight Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00641-8

Pearl RL, Hopkins CH, Berkowitz RI, Wadden TA (2018) Group cognitive-behavioral treatment for internalized weight stigma: a pilot study. Eat Weight Disord 23(3):357–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0336-y

The Statistical Report of the Islamic Republic of Iran (2017) The Iranian Authority for General Department of Public Statistics and Statistical Center of Iran. https://www.amar.org.ir/. Accessed 26 Mar 2018

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2018) About Child & Teen BMI. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html. Accessed 26 Mar 2018

Bahreynian M, Qorbani M, Khaniabadi BM, Motlagh ME, Safari O, Asayesh H, Kelishadi R (2017) Association between Obesity and Parental Weight Status in Children and Adolescents. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 9(2):111–117. https://doi.org/10.4274/jcrpe.3790

Pakpour AH, Zeidi IM, Yekaninejad MS, Burri A (2014) Validation of a translated and culturally adapted Iranian version of the International Index of Erectile Function. J Sex Marital Ther 40(6):541–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2013.788110

Wang Y, Chen HJ (2012) Use of percentiles and z -scores in anthropometry. In: Preedy VR (ed) Handbook of anthropometry: physical measures of human form in health and disease. Springer, London, pp 29–48

Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH (1995) The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther 33(3):335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

Asghari A, Saed F, Dibajnia P (2008) Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21) in a non-clinical Iranian sample. Int J Psychol 2(2):82–102

Lin CY, Broström A, Nilsen P, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH (2017) Psychometric validation of the Persian Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale using classic test theory and Rasch models. J Behav Addict 6(4):620–629. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.071

Szabó M (2010) The short version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): factor structure in a young adolescent sample. J Adolesc 33(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.05.014

Parcel GS, Edmundson E, Perry CL, Feldman HA, O’Hara-Tompkins N, Nader PR, Johnson CC, Stone EJ (1995) Measurement of self-efficacy for diet-related behaviors among elementary school children. J Sch Health 65(1):23–27

Pakpour AH, Gellert P, Dombrowski SU, Fridlund B (2015) Motivational interviewing with parents for obesity: an RCT. Pediatrics 135(3):e644–e652. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-1987

Clark MM, King TK (2000) Eating self-efficacy and weight cycling: a prospective clinical study. Eat Behav 1(1):47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1471-0153(00)00009-X

Mirkarimi K, Kabir MJ, Honarvar MR, Ozouni-Davaji RB, Eri M (2017) Effect of motivational interviewing on weight efficacy lifestyle among women with overweight and obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Iran J Med Sci 42(2):187–193

Walpole B, Dettmer E, Morrongiello BA, McCrindle BW, Hamilton J (2013) Motivational interviewing to enhance self-efficacy and promote weight loss in overweight and obese adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Psychol 38(9):944–953. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jst023

Lin CY (2018) Comparing quality of life instruments: Sizing Them Up versus PedsQL and Kid-KINDL. Soc Health Behav 1:42–47. https://doi.org/10.4103/SHB.SHB_25_18

Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS (2001) PedsQL™ 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ Version 4.0 Generic Core Scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care 39(8):800–812

Pakpour AH (2013) Psychometric properties of the Iranian version of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ Short Form 15 Generic Core Scales. Singap Med J 54(6):309–314. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2013123

Shapurian R, Hojat M, Nayerahmadi H (1987) Psychometric characteristics and dimensionality of a Persian version of Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale. Percept Mot Skills 65(1):27–34

Pakpour AH, Chen CY, Lin CY, Strong C, Tsai MC, Lin YC (2018) The relationship between children’s overweight and quality of life: a comparison of sizing me up, PedsQL and Kid-KINDL. Int J Clin Health Psychol 19(1):49–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2018.06.002

Welch E, Lagerström M, Ghaderi A (2012) Body Shape Questionnaire: psychometric properties of the short version (BSQ-8C) and norms from the general Swedish population. Body Image 9(4):547–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.04.009

Veisy F, Ahmadi SM, Sadeghi K, Rezaee M (2018) The psychometric properties of Body Shape Questionnaire C8 in women with eating disorders. Iran J Psychiatry Clin Psychol 23(4):480–493. https://doi.org/10.29252/nirp.ijpcp.23.4.480

Akdemir A, Inandi T, Akbas D, Karaoglan Kahilogullari A, Eren M, Canpolat BI (2012) Validity and reliability of a Turkish version of the body shape questionnaire among female high school students: preliminary examination. Eur Eat Disord Rev 20(1):e114–e115. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1106

Johns MW (2015) The assessment of sleepiness in children and adolescents. Sleep Biol Rhythm 13(Suppl 1):97

Imani V, Lin CY, Jalilolghadr S, Pakpour AH (2018) Factor structure and psychometric properties of a Persian translation of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale for Children and Adolescents. Health Promot Perspect 8(3):200–207. https://doi.org/10.15171/hpp.2018.27

Maskey R, Fei J, Nguyen HO (2018) Use of exploratory factor analysis in maritime research. Asian J Shipp Logist 34(2):91–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajsl.2018.06.006

Bagozzi RP, Yi Y (1988) On the evaluation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci 16:74–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

Linacre JM (2002) What do infit and outfit, mean-square and standardized mean? https://www.rasch.org/rmt/rmt162f.htm. Accessed 26 Mar 2018

Shih CL, Wang WC (2009) Differential item functioning detection using the multiple indicators, multiple causes method with a pure short anchor. Appl Psychol Meas 33(3):184–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146621608321758

Enders C, Bandalos D (2001) The relative performance of Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Struct Eq Mod 8(3):430–457

Lin KP, Lee ML (2017) Validating a Chinese version of the weight self-stigma questionnaire for use with obese adults. Int J Nurs Pract 23(4):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12537

Lin CY, Strong C, Tsai MC, Lee CT (2017) Raters interpret positively and negatively worded items similarly in a quality of life instrument for children: Kid-KINDL. Inquiry 54:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/0046958017696724

Essayli JH, Murakami JM, Wilson RE, Latner JD (2017) The impact of weight labels on body Image, internalized weight stigma, affect, perceived health, and intended weight loss behaviors in normal-weight and overweight college women. Am J Health Promot 31(6):484–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117116661982

Chan KL, Lee CSC, Cheng CM, Hui LY, So WT, Yu TS, Lin CY (2019) Investigating the relationship between weight-related self-stigma and mental health for overweight/obese children in Hong Kong. J Nerv Ment Dis. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001021

Souza AC, Alexandre NMC, Guirardello EB (2017) Psychometric properties in instruments evaluation of reliability and validity. Epidemiol Serv Saude 26(3):649–659. https://doi.org/10.5123/S1679-49742017000300022

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, CY., Imani, V., Cheung, P. et al. Psychometric testing on two weight stigma instruments in Iran: Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire and Weight Bias Internalized Scale. Eat Weight Disord 25, 889–901 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00699-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00699-4