Abstract

Background

The current study investigates determinants of treatment evaluation by adolescent outpatients with anorexia nervosa (AN) and the accordance with their parents’ and psychotherapists’ evaluation.

Sampling and methods

The sample included 50 female adolescent outpatients (mean age: 16.9 ± 1.8) with AN (DSM-IV). They were randomly assigned to either cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) or dialectical-behavior therapy (DBT). Before (T1) and after treatment (T2) diagnostic interviews as well as self-report questionnaires were administered measuring eating disorder-specific and general psychopathology. The subjective evaluation of the therapy was assessed by a self-report questionnaire. Data on the evaluation of treatment of 42 parents were considered as well as treatment evaluations of the therapists for 48 patients.

Results

Our results revealed significant correlations of treatment satisfaction between parents and therapists, whereas patients and therapists as well as patients and parents did not agree in their treatment evaluation. The change in body mass index (BMI) was a significant predictor of the patients’ treatment satisfaction.

Conclusion

Adolescent patients displaying high severity of AN at the beginning of treatment put little emphasis on the importance of body weight even after treatment. Satisfaction ratings of this special group of patients could be heavily distorted and have to be interpreted carefully.

Level of evidence

Level I, randomized controlled trial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Evidence-based clinical practice should rely on clinical expertise, the best research evidence as well as patient values. The integration of these aspects into the decision process for patient treatment makes good clinical outcomes and increased quality of life more likely [1]. Patients with eating disorders (EDs) and their carers are important sources concerning treatment perceptions, particularly the perceived efficacy and their satisfaction with treatment [2]. In addition to patients’ and parents’ perspectives on treatment of EDs, the view of therapists could provide recommendations to improve the treatment of EDs. A comparison of patients’ and therapists’ treatment evaluations [3] indicated that both therapists and patients rated as important aspects of the quality of treatment the focus of treatment, therapeutic alliance, and communicational skills. However, they valued similar topics differently. Therapists evaluated the focus on ED symptoms and behavioral change higher, whereas patients rated the therapeutic relationship and addressing underlying problems as particularly important. Moreover, patient dissatisfaction with treatment may cause to treatment delay, failure to engage and to treatment discontinuation [4, 5]. Thus, it is of particular importance to investigate the subjective evaluation of treatment from the patients’, parents’ and therapists’ point of view to improve the treatment of EDs [2, 4]. However, there are only a few studies available analyzing treatment satisfaction of adolescent patients with EDs, especially with anorexia nervosa (AN). These studies found an overall high level of satisfaction from the patients’, parents’ and therapists’ perspective [6,7,8]. Schneider et al. [8] identified a relationship between satisfaction and treatment outcome in adolescents with AN or BN, their parents and therapists after inpatient treatment with dialectical-behavior therapy (DBT). The body mass index (BMI) change had a prognostic impact on the parents’ satisfaction. Furthermore, a relationship between satisfaction from the patients’ and parents’ perspective and the BMI at the beginning of inpatient treatment could be indicated. Moreover, the results displayed no conformities of the parents’ and the therapists’ satisfaction ratings, but the ratings of patients and parents as well as of patients and therapists showed a meaningful accordance. A recent study [9] investigated patient and parent perspectives on the helpfulness of family-based therapy (FBT) and whether these evaluations are linked to changes in ED symptoms. Both patients and their parents evaluated FBT as helpful, but improvements in eating-related psychopathology were associated with adolescents’ perceptions of helpfulness, while physical improvements were associated with mothers’ perceptions of helpfulness.

The existing research concerning the subjective evaluation of psychotherapy of adolescents with AN is quite limited. Due to methodological limitations, such as small sample sizes, the use of inconsistent definitions of treatment satisfaction or different treatment settings, the results of present studies are difficult to interpret.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to examine, as secondary analysis of our randomized controlled trial comparing cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) and DBT in adolescents with AN [10], the subjective evaluation of the two mentioned outpatient therapy approaches in AN patients and the accordance with their parents’ and therapists’ evaluations. Furthermore, the role of treatment satisfaction as an indicator of objective treatment outcome should be analyzed. We investigated these two treatment approaches due to the need for effective treatments for patients and families, for whom FBT as the treatment approach with the strongest evidence base for effectiveness in adolescents with AN is not suitable.

We hypothesized that there are correlations between the treatment satisfaction ratings of (a) parents and therapists, (b) patients and parents, and (c) patients and therapists. Additionally, we supposed an association between treatment satisfaction and symptom change during therapy.

Sampling and methods

Participants

All patients were recruited from a CBT-based specialized eating disorder unit at the child and adolescent psychiatric department of a major university hospital in Germany between 2006 and 2011. Inclusion criteria encompassed female adolescents with a diagnosis of AN as well as an indication for outpatient treatment due to AN. Exclusion criteria were a diagnosis of BN or EDNOS, an IQ < 85 tested by using the CFT-20-R (Culture Fair Intelligence Test 20-Revised; German Version) [11] as well as additional psychotherapeutic treatment. Regarding psychotropic medication, patients had not be naïve at the beginning of the study. The ED diagnosis according to DSM-IV [12] was confirmed by the Structured Inventory for Anorexic and Bulimic Syndromes (SIAB-EX) [13]. The German version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI-DIA-X) [14] was used to screen all patients for psychiatric comorbidities.

All participants and their parents had received detailed information about the study. Patients could only participate in the study if they and their parents had provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

The total sample of the study is a subsample of a randomized controlled trail comparing CBT and DBT with a waiting-list condition (WLC) in adolescents with AN [10] consisted of 50 female outpatients with AN [AN-R: 41 (82%)], AN binge-purging type [AN-BP: 9 (18%)]. The mean age of the participants was 16.9 (± 1.8) years. 24 (48%) patients were treated with CBT and 26 (52%) with DBT. Before starting outpatient treatment 5 (20.8%) patients of the CBT group as well as 5 patients (19.2%) of the DBT group were assigned to a 12-week WLC. During the waiting period, they received supportive counselling every 2 weeks. Specific psychotherapeutic strategies were not applied. For the present study, however, only the data of the two time points, before (T1) and after outpatient treatment (T2), were considered.

Furthermore, data on the evaluation of treatment of 42 parents were considered as well as treatment evaluations of the therapists for 48 patients.

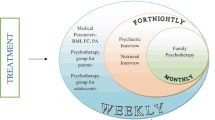

Outpatient treatment

Patients were randomly assigned to 25 weeks of outpatient treatment, either CBT or DBT using the procedure of blocked randomization. Both treatment conditions based on standardized treatment manuals and were provided by different trained therapists. The two treatment approaches mentioned have been described in detail elsewhere [10]. If necessary, patients received additional psychotropic medication. The indications of phychopharmacological interventions were made by the senior child and adolescent psychiatrist based on treatment guidelines.

Cognitive-behavior therapy

The CBT approach used in the present study based on the CBT programme for adults with eating disorders of Jacobi et al. [15]. It was adapted to children and adolescents with AN and BN, including 25 sessions of individual therapy and 25 sessions of group therapy. As an age-specific modification parents participated in 5 sessions of individual therapy as well as in 8 sessions of group therapy [10, 16]. Both individual sessions and family sessions were conducted by the same therapist.

Dialectical-behavior therapy

The DBT programme had originally been developed by Linehan [17] for the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorders. Meanwhile, this therapy approach has been adapted to adolescent and adult patients with other psychiatric disorders [18]. In this study we conducted a modified DBT programme for adolescents with AN or BN (DBT-AN/BN), which was developed by Salbach-Andrae et al. [10].

In the present study, patients received 25 sessions of individual therapy and 25 sessions of DBT skills training in a group. As in the CBT arm, parents took part in 5 sessions of individual therapy and in 8 sessions of group skills training. Individual sessions as well as family sessions were conducted by the same therapist.

Procedure

At two time points, before (T1) and after outpatient treatment (T2), the SIAB-EX [13], the Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2) [19] and the Symptom-Checklist-90-R of Derogatis (SCL-90-R) [20] were used to determine eating disorder-specific and general psychopathology. Furthermore, for each participant body height (m) and body weight (kg) were measured to calculate the body mass index (BMI = kg/m2) and the BMI-percentile. Participants were weighed wearing light clothing (without shoes).

Prior to outpatient treatment (T1) the CIDI-DIA-X [14] was used to screen for psychiatric comorbidities according to the DSM-IV criteria.

After treatment (T2), patients, their parents and therapists completed the self-report questionnaire “Questionnaire for the evaluation of treatment” (German version, FBB) [21] to assess satisfaction with outpatient treatment.

Measurements

Composite international diagnostic interview

The CIDI-DIA-X [14] is a standardized diagnostic interview to assess psychiatric disorders according to DSM-IV [12] criteria.

The test–retest reliability ranged between 0.49 and 0.83, the interrater-reliability ranged between 0.82 and 0.98. The construct validity of the CIDI-DIA-X is similar to other structured diagnostic interviews [14]. In the present study, the CIDI-DIA-X was conducted by trained research assistants under the supervision of the attending child and adolescent psychiatrist to screen for psychiatric comorbidities.

Structured inventory for anorectic and bulimic syndromes

The SIAB-EX [13] represents a semi-structured interview that measures the presence and severity of specific eating-related psychopathology over the previous three months. It can be used for people aged between 16 and 65 and provides diagnoses of eating disorders according to DSM-IV.

The interview has a good interrater-reliability, κ = 0.81, and good internal consistency, Cronbach’s α ranged between 0.53 and 0.93 [13]. In the current study, the SIAB-EX was also conducted by clinically experienced and trained research assistants under the supervision of the attending child and adolescent psychiatrist.

Symptom-checklist 90-revised

The SCL-90-R [20] is a self-report measure to quantify physical and psychological symptoms within the previous seven days. The questionnaire consists of the nine subscales “somatization”, “obsessive-compulsive”, “interpersonal sensitivity”, “depression”, “anxiety”, “hostility”, “phobic anxiety”, “paranoid ideation” and “psychoticism”. It has a good internal consistency with Cronbach’s α between 0.74 and 0.97 [20]. In the present study the global severity index (GSI) that provides information about the overall psychological state of a person was considered.

Eating disorder inventory-2

The EDI-2 [19, 22] is a self-report questionnaire to assess the eating disorder-specific psychopathology. In the present study the short version with the eight subscales “drive for thinness”, “bulimia”, “body dissatisfaction”, “ineffectiveness”, “perfectionism”, “interpersonal distrust”, “interoceptive awareness”, and “maturity fears” was used. The EDI-2 has a good reliability, with Cronbach’s α between 0.73 and 0.93, and validity in eating disordered samples. The EDI-2 total score as an indicator of the degree of eating disorder-specific psychopathology was applied in this study.

Questionnaire for the evaluation of treatment

The subjective evaluation of the therapy was determined by using the Questionnaire for the Evaluation of Treatment (German version, FBB [21]). The FBB is a self-report questionnaire to measure aspects of outcome quality as well as the quality of treatment course from the patients’, parents’ and therapists’ perspectives. There is a special version of the questionnaire for each of the three groups mentioned. The version for patients includes the subscales “therapeutic outcome”, “relationship with the therapist”, and “general conditions of the treatment”, whereas the version for parents encompasses the two subscales “therapeutic outcome” and “course of treatment”. The version for therapists consists of the following subscales: “therapeutic outcome with regard to the patient”, “therapeutic outcome with regard to the family”, “cooperation with the patient”, “cooperation with the mother”, and “cooperation with the father”. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) of the subscales averages α = 0.80. The test–retest reliability of the three questionnaire versions ranged between r = 0.68 and r = 0.77 [21]. In this study the total score was considered, representing the overall satisfaction with outpatient treatment.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows version 21.0. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Pairwise comparisons of the variables BMI, EDI-2 total score, and SCL-GSI were conducted, using t tests for paired samples. All assumptions were fulfilled.

To determine the conformities between the three raters, non-parametric correlations (Spearman rs) were applied, since the requirement of normal distribution was not given. The effect sizes were interpreted according to Cohen [23].

Furthermore, hierarchical regression analyses were used to identify the relationship between treatment satisfaction and symptom change. All requirements for this calculation were checked and all continuous variables were centered.

In the regression model the control variables therapy group (TG; CBT and DBT) and WLC were included in the first step. In the second step the variables marking symptom change (DIF (difference) EDI-2, DIF GSI und DIF BMI) and the existence of an eating disorder at T2 (DIAGNOSIS T2) were entered as predictors. In the final step EDI-2 T1, GSI T1 and BMI T1 were added as well as the variables describing the interactions of differences and symptom strain at T1 (DIF EDI-2*EDI-2 T1, DIF GSI*GSI T1 and DIF BMI*BMI T1) were appended.

All necessary assumptions (linearity, non-existence of multicollinearity, homoscedasticity, normality of residuals, free of measurement error) needed for calculating the hierarchical regression analyses were given.

Results

Study sample

The total sample consisted of 50 female AN outpatients with a mean age of 16.9 years (± 1.8). CBT treatment was given to 24 (48%) patients and 26 (52%) patients received DBT treatment. Differences between the treatment groups (CBT and DBT) regarding sample characteristics could not be detected. Further sample characteristics are presented in Table 1.

The symptoms improved during the course of the study for the total sample as well as for the treatment groups. In the total sample the eating disorder-specific symptoms measured by EDI-2 (t = 4.14; p < .001***; d = 1.28) as well as the general symptom strain measured by GSI (t = 4.46; p < .001***; d = 1.35) decreased significantly between T1 and T2. The BMI (t = − 4.65; p < .001***; d = 1.16) on the contrary increased significantly.

Concerning the therapy conditions (CBT, DBT), the eating disorder-specific symptoms measured by EDI-2 decreased significantly in the CBT (t = 3.34; p = .003**; d = − 0.61) and the DBT group (t = 2.61; p = .016**; d = − 0.55). Additionally, the general symptom strain assessed by the GSI lowered in the CBT group (t = 3.67; p = .001**; d = 0.78) as well as in the DBT group (t = 2.63; p = .015*; d = 0.47). Furthermore, in the CBT group (t = − 3.35; p = .003**; d = 1.04) and in the DBT group (t = − 3.48; p = .002**; d = 0.7) the BMI increased significantly.

Descriptive results of treatment satisfaction

The mean satisfaction scores concerning the patients’ (M = 2.9, SD = 0.6, N = 29), parents’ (M = 2.9, SD = 0.6, N = 26) and therapists’ evaluation (M = 2.3, SD = 0.5, N = 32) are presented in Fig. 1.

Conformities between the three raters

Significant correlations regarding the accordance of satisfaction between parents and therapists (N = 23; rs = 0.67; p < .001***) were found. Neither patients and therapists (N = 26; rs = 0.30; p = .132) nor patients and parents (N = 23; rs = 0.37; p = .076) agreed in their satisfaction with the treatment (see Table 2).

Determinants of treatment satisfaction

Patients’ treatment satisfaction (FBB-P)

The total regression model for the dependent variable FBB-P explained 54% of the variance without statistical significance (R2 = 0.540; p = .416).

The only variable showing a significant effect on satisfaction was the difference in BMI (β = − 0.97; SE = 0.06; p < .039*) in regression step 3. Therefore, the effect has to be interpreted as a function of the interaction of the BMI difference and the BMI at baseline (T1). This relationship is illustrated in Fig. 2 and shows that the higher the BMI was at baseline (T1), and the smaller (more negative) the difference in BMI was at the end of treatment (T2), the more satisfied patients were with the treatment. This means the higher the BMI was at T1 and the more the BMI increased during treatment, the more satisfied were the patients.

Furthermore, Fig. 2 depicts that the lower the BMI was at T1, the lesser impact the difference in BMI had on satisfaction. The change in body weight from T1 to T2 had a smaller effect on satisfaction for patients with a lower body weight at T1.

The kind of therapy (CBT or DBT) could not predict treatment satisfaction either.

Parents’ (FBB-Par) and therapists’ (FBB-T) treatment satisfaction

The total regression model explained for the dependent variable FBB-Par 34% of the variance (R2 = 0.342; p = .819). For the dependent variable FBB-T the explained variance was 49% (R2 = 0.490; p = .172). In both models there was no variable showing a prognostic impact on the dependent variables. The therapy condition (CBT or DBT) could not predict treatment satisfaction either.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to examine the subjective evaluation of two outpatient therapy approaches, either CBT or DBT, in adolescent outpatients with AN and the accordance with their parents’ and therapists’ evaluations. Our results revealed significant correlations regarding the accordance of satisfaction between parents and therapists, whereas neither patients and therapists nor patients and parents agreed in their treatment evaluation.

In contrast to previous findings [8], we neither observed an agreement between patients’ and therapists’ nor between patients’ and parents’ treatment satisfaction. These inconsistent results might rely on methodological differences. In the study of Schneider et al. [8] patients were treated in an inpatient setting, whereas the present study included outpatients. An inpatient setting allows more contact between patients and therapists, but less contact between patients and parents in contrast to outpatient treatment. Furthermore, the lack of agreement between both patients and therapists as well as between patients and parents could be the result of different criteria used for their treatment evaluation [21].

Regarding determinates of treatment satisfaction, most of the studied predictors showed no prognostic impact on treatment satisfaction from the patients’, parents’ and therapists’ perspectives. The symptom change as well as the kind of therapy condition (CBT or DBT) could not predict the treatment satisfaction from the parents’ and therapists’ perspectives.

The change in BMI depending on the BMI at the beginning of therapy was the only meaningful predictor of patient satisfaction. This result indicates that the smaller the BMI was at the beginning of therapy, the less influence shows weight increase on treatment satisfaction during the course of treatment. A possible explanation is that patients with severe AN put little emphasis on the importance of body weight even after treatment [24]. Our results are consistent with studies underlining that the major challenge in treating AN patients is the ambivalent motivation for change [25,26,27]. Particularly AN patients with persistent ED symptoms and a chronic course are difficult to treat and have poor treatment outcomes [28, 29].

Another important result is that symptom change had no prognostic impact on treatment satisfaction from the patients’, parents’ and therapists’ perspectives. Thus, other variables appear to be relevant to predict treatment satisfaction in patients with AN, their parents and therapists. In future research potential predictors describing symptom change, e.g., therapy process, therapeutic alliance, therapists’ characteristics, expectations of therapy as well as the self-evaluated therapy success (in comparison to the objective measurable success in the present study), should be emphasized [3].

The findings of the present study must be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, the ratings of dropouts were not assessed due to the study design of a completer analysis. Second, the small sample size, the non-parametric methods used, and the high number of predictors could have caused a relatively low test power of the analyses. Third, the satisfaction scores showed high values and low variability, which could be distorted by social desirability [21]. Fourth, our results are limited due to the lack of assessing parents and therapists characteristics as well as further parameters which could have had an impact on treatment satisfaction, such as therapy process variables, therapeutic relationship, and patients’ and parents’ expectations of therapy. The presence of comorbidities and the use of psychotropic medication in a subsample, the small number of AN-BP patients, and the absence of a control group limited our results as well. Furthermore, due to the inclusion of an exclusively female sample, our study results cannot be generalized. Thus, in future studies male samples should be considered.

In spite of these limitations, the present study is to our awareness the first one that compares treatment satisfaction with two outpatient psychotherapy approaches (CBT and DBT) for adolescent patients with AN. Strengths of the present study are a differentiated assessment of satisfaction by a five-stepped Likert-scale of the FBB [21] in contrary to undifferentiated and global satisfaction-measures of previous studies. Additionally, the structured assessment of diagnoses by the SIAB-EX [13] and the manualized therapy are important strengths of the study. Therefore, our study delivers a crucial contribution to psychotherapy research of EDs. Patients with EDs and their parents are important sources concerning treatment perceptions, particularly the perceived efficacy and their satisfaction with treatment. Patient dissatisfaction with treatment may cause to treatment delay, failure to engage and to treatment discontinuation [4, 5]. Further research is necessary on treatment satisfaction from the patients’, parents’ and therapists’ point of view to improve the treatment of EDs and reduce dropout rates.

The results of our study imply that treatment outcome of adolescent outpatients with AN does not predict the subjective treatment satisfaction. Thus, treatment satisfaction neither should be used to evaluate the therapists’ performance, nor should it be applied for the rating of the therapy success as a single measure, but always has to be complemented by objective criteria of symptom change, e.g., BMI. Adolescent patients displaying high severity of the eating disorder symptoms at the beginning of treatment seem to put little emphasis on the importance of body weight even after treatment. As a result the satisfaction rating of this special group of patients could be heavily distorted and has to be interpreted carefully.

References

Sackett D, Strauss S, Richardson S, Rosenberg W, Haynes BR (2000) Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh

Newton T (2001) Consumer involvement in the appraisal of treatments for people with eating disorders: a neglected area of research? Eur Eat Disord Rev 9:301–308. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.435

de la Rie S, Noordenbos G, Donker M, van Furth E (2008) The quality of treatment of eating disorders: a comparison of the therapists’ and the patients’ perspective. Int J Eat Disord 41:307–317. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20494

Bell L (2003) What can we learn from consumer studies and qualitative research in the treatment of eating disorders? Eat Weight Disord Stud Anorex Bulim Obes 8:181–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03325011

de la Rie S, Noordenbos G, Donker M, van Furth E (2006) Evaluating the treatment of eating disorders from the patient’s perspective. Int J Eat Disord 39:667–676. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20317

Klinkowski N, Korte A, Lehmkuhl U, Pfeiffer E, Salbach H (2007) Dialektisch-Behaviorale Therapie für jugendliche Patientinnen mit Anorexia und Bulimia nervosa (DBT-AN/BN)—eine Pilotstudie. Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr 56:91–108. https://doi.org/10.13109/prkk.2007.56.2.91

Kopec-Schrader EM, Marden K, Rey JM, Touyz SW, Beumont PJV (1993) Parental evaluation of treatment outcome and satisfaction with an inpatient program for eating disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 27:264–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048679309075775

Schneider N, Korte A, Lenz K, Pfeiffer E, Lehmkuhl U, Salbach-Andrae H (2010) Subjective evaluation of DBT treatment by adolescent patients with eating disorders and the correlation with evaluations by their parents and psychotherapists. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother 38:51–57. https://doi.org/10.1024/1422-4917.a000006

Singh S, Accurso EC, Hail L, Goldschmidt AB, Grange DL (2018) Outcome parameters associated with perceived helpfulness of family-based treatment for adolescent eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 51:574–578. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22863

Salbach-Andrae H, Bohnekamp I, Bierbaum T, Schneider N, Thurn C, Stiglmayr C, Lenz K, Pfeiffer E, Lehmkuhl U (2009) Dialektisch behaviorale therapie (DBT) und kognitiv behaviorale therapie (CBT) für Jugendliche mit Anorexia und Bulimia nervosa im Vergleich. Kindh Entwickl 18:180–190. https://doi.org/10.1026/0942-5403.18.3.180

Weiß RH (2016) Grundintelligenztest Skala 2—revision (CFT 20-R) mit Wortschatztest und Zahlenfolgentest—Revision (WS/ZF-R). Hogrefe, Göttingen

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. American Psychiatric Association, Washington

Fichter M, Quadflieg N (2001) The structured interview for anorexic and bulimic disorders for DSM-IV and ICD-10 (SIAB-EX): reliability and validity. Eur Psychiatry 16:38–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(00)00534-4

Wittchen H-U, Pfister H (1996) DIA-X-diagnostisches expertensystem für ICD-10 und DSM-IV. Swets, Frankfurt

Jacobi C, Thiel A, Paul T (2000) Kognitive Verhaltenstherapie bei Anorexia und Bulimia nervosa. Beltz, Weinheim

Salbach-Andrae H, Jacobi C, Jaite C (2010) Anorexia und Bulimia nervosa im Jugendalter. Kognitiv-verhaltenstherapeutisches Behandlungsmanual. Beltz, Weinheim

Linehan MM (1993) Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford, New York

Ritschel LA, Lim NE, Stewart LM (2015) Transdiagnostic applications of DBT for adolescents and adults. Am J Psychother 69:111–128. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2015.69.2.111

Paul T, Thiel A (2004) Eating disorder inventory-2 (EDI-2). Hogrefe, Göttingen

Franke GH (2002) Symptom-checkliste (SCL-90-R). Hogrefe, Göttingen

Mattejat F, Remschmidt H (1998) Fragebögen zur Beurteilung der Behandlung (FBB). Hogrefe, Göttingen

Rathner G, Waldherr K (1997) Eine deutschsprachige Validierung mit Normen für weibliche und männliche Jugendliche [Eating disorder inventory-2: a German language validation with norms for female and male adolescents]. Z Für Klin Psychol Psychiatr Psychother 45(2):157–182

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2th edn. Erlbaum, Hillsdale

Serpell L, Treasure J, Teasdale J, Sullivan V (1999) Anorexia nervosa: friend or foe? Int J Eat Disord 25:177–186 https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199903)25:2%3C177::AID-EAT7%3E3.0.CO;2-D

Abbate-Daga G, Amianto F, Delsedime N, De-Bacco C, Fassino S (2013) Resistance to treatment and change in anorexia nervosa: a clinical overview. BMC Psychiatry 13:294. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-294

Hillen S, Dempfle A, Seitz J, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Bühren K (2015) Motivation to change and perceptions of the admission process with respect to outcome in adolescent anorexia nervosa. BMC Psychiatry 15:140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0516-8

Mander J, Teufel M, Keifenheim K, Zipfel S, Giel KE (2013) Stages of change, treatment outcome and therapeutic alliance in adult inpatients with chronic anorexia nervosa. BMC Psychiatry 13:111. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-111

Hay PJ, Touyz S, Sud R (2012) Treatment for severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: a review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 46:1136–1144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867412450469

Hay P, Touyz S (2015) Treatment of patients with severe and enduring eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 28:473–477. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000191

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the Stiftung RTL–Wir helfen Kindern e.V. The authors wish to thank the adolescents and their families who participated in the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declared no conflicting interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the university’s Institutional Review Board and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jaite, C., Pfeiffer, A., Pfeiffer, E. et al. Subjective evaluation of outpatient treatment for adolescent patients with anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord 25, 445–452 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0620-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0620-0