Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to assess the adaptability and acceptability of a prevention program.

Methods

A total of 169 Korean students (83 boys and 86 girls) with a mean age of 12.3 years from a 6th grade class at an elementary school participated in the study. Mental health social workers delivered Me, You and Us, a school-based body image intervention program originally developed in the UK, through a set of six sessions. The participants were assessed in terms of their body satisfaction and self-esteem before the program, after the program, and at 1-month follow-up. They were also surveyed about their satisfaction and acceptability levels after the program.

Results

At baseline, girls had lower body satisfaction and self-esteem than boys, and their body satisfaction and self-esteem improved after the program. The improved body satisfaction was maintained at the 1-month follow-up. The efficacy of the program on body satisfaction was positively correlated with the frequency of their baseline level of “fat talk.” The program was more effective in girls with possible symptoms of an eating disorder at baseline. 93.7% of boys and 77.4% of girls responded that they enjoyed the program.

Conclusions

The program Me, You and Us was well-accepted by early adolescents in Korea and it can play a role in increasing body satisfaction and self-esteem by reducing “fat talk” in 6th grade students.

Level of evidence

Level III, cohort study with intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The incidence of eating disorders peaks at ages 15–19, but early symptoms are common from the pre-adolescence and early adolescence years [1,2,3]. Childhood body dissatisfaction has been shown to strongly predict eating disorders in girls [4]. It follows that modifying body perceptions may prevent eating disorders.

The risk factors for eating disorders have been established [1, 5, 6], and many prevention programs target these factors. The recent generation of prevention programs includes more interactive content and persuasion principles from social psychology [7]. Most preventive interventions target the individual but a wider community focus may be more appropriate [8].

School-based interventions provide an opportunity to provide programs that support environmental changes [9] and school-wide approaches to health promotion [10, 11]. School-based preventive interventions addressing eating disorders and body image issues for adolescents have been successful [12,13,14]. Those found to be effective tend to (a) target younger adolescents aged 12–13 years, (b) include some media literacy, self-esteem and peer-focused content, but not psychoeducation, and (c) have a multi-session format with an average of 5.02 h in total program length [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

“Fat talk”, a ritualized form of negative commentary about weight and shape [23], is causally implicated as a proximal risk factor for disordered eating, body dissatisfaction, and negative affect and has the potential to be modified [24, 25]. Interventions to modify an individual’s fat talk may positively impact on both the individual and their friendship group [24]. The intervention “Me, You and Us” is a school-based prevention program developed in the UK to promote body satisfaction [26], focusing on peer interactions, specifically in relationship to “fat talk”, why this occurs, how it can be stopped and how to counter it by activities on giving and receiving compliments from others. In a randomized, controlled trial of the program, students in the intervention group exhibited a significant improvement in body esteem and self-esteem, as well as a reduction in thin-ideal internalization both at the end of treatment and 3 months later [26].

Body dissatisfaction is of concern for both genders [27]. School-based interventions have achieved modest improvements in body satisfaction in both girls and boys [28,29,30]. A program reported significant improvements in body image at post-test that were sustained until 6-months follow-up in boys [21].

Although few representative epidemiologic data are available for Asian populations, available evidence shows that eating disorders and associated attitudes and behaviors are also prevalent across these regions [31]. The dramatic cultural shift with rapid Westernization has prompted adolescents in Korea to accept Western ideals of beauty, and the resulting thin-body idealization has increased body dissatisfaction in Korea [32]. The pursuit of a thin physique in Korea has been widespread for individuals in their early teens. Among the students in 5th and 6th grades in Korea (11–12 years old), 23% of girls and 11.5% of boys within a normal weight range estimated that they were overweight [33]. Overall, 23.9% of Korean middle school students (27.8% of middle school girls) who were normal or under-weight estimated that they were fat, and the number increased to 38.1% in high school girls [34]. 32.2% of Korean middle school students (43.8% of middle school girls) tried to lose weight, and 16.0% of those who sought to lose weight (18.1% of middle school girls) engaged in pathologic eating-disordered behavior, such as purging, laxative abuse, or starvation [34]. Korean adolescents aged 12–15 years have higher levels of body dissatisfaction than children aged 9–11 years [35], and body dissatisfaction and a disordered body image result in a decrease in self-esteem [36].

As there is no overall difference in the childhood risk factors for anorexia nervosa in Korean women compared to the established risk factors in the UK [37], we considered that the prevention program developed in the UK can be adapted to Korean adolescents. In Korea, despite the apparent necessity to prevent problems related to body image and eating behavior, the current school education curriculum does not address body image problems nor does it attempt to prevent these pernicious and seemingly increasing problems. As there could be limitations in conducting Western-based intervention programs in another culture without appropriate cultural awareness [38], we were interested in determining whether an intervention program adopted from the Me, You and Us program could be applied to Korean students.

The aims of this study were to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of implementing the Me, You and Us eating disorder prevention program for 6th grade girls and boys at an elementary school in Korea and to explore gender differences in the reaction to the program.

Materials and methods

Designs

All subjects were included in a single-arm prospective cohort study and participated in the program. Body esteem and self-esteem were measured at pre-intervention, post-intervention, and at 1-month follow-up of the program.

Participants

All of the 6th grade students in six classrooms at an elementary school in the city of Goyang, Gyeung-gi province, South Korea participated in the intervention (N = 169 in all; n = 29 in class 1, n = 28 in each of classes 2–6). Five students moved away to other schools for educational reasons; thus, 164 students completed the final follow-up assessment.

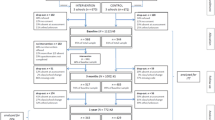

All participants were deemed by their teachers to have sufficient ability in comprehending the program. Informed consents were received from a parent or a guardian for each of the students. The assessments were made at baseline (pre-intervention), after the intervention (post-intervention), and at 1-month follow-up. The flowchart describing study participants is shown in Fig. 1. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Seoul Paik Hospital of Inje University [ITT-2016-104].

Intervention

Permission to use the Me, You and Us program in our study was obtained from Helen Sharpe. All materials for the sessions, including the instruction manual, workbooks, and PowerPoint™ slides, were translated into Korean by two bilingual, fluent in both English and Korean, psychology students studying for their Bachelor of Science degrees in the United States. We modified the Western media images and YouTube™ clips for the topic ‘Happiness’ from the original program using Korean images familiar to the Korean students. A focus group consisting of mental health professionals and school teachers reviewed all of the materials and confirmed that the materials were appropriate for 6th grade students in Korea.

The program Me, You and Us consisted of six sessions of 1-h lesson per week, as in the original program. The program targeted three different areas of risk: societal risk, peer group risk, and individual risk. ‘Societal risk’ referred to the internalization of the ideal of thinness as shown in the media, for which the intervention focused on media literacy; the ‘peer group risk’ referred to the experience of “fat talk” with friends, for which the intervention focused on peer interaction; and the ‘individual risk’ referred to mood and anxiety levels, for which the intervention focused on boosting mood and self-esteem [26].

The intervention was delivered by mental health social workers who were trained for the program from October to November of 2015, with a follow-up completed in December of 2015. Training for the instructors consisted of 6-h workshops run by one of the researchers, Y-R. K. One main instructor and a co-instructor delivered the sessions in a class. A school teacher monitored all sessions in a sample class.

Outcomes

All outcomes were assessed using questionnaires as participants’ self-reports. Screening for eating disorders was conducted using the SCOFF questionnaire [39]. The participants were not explicitly made aware of the hypothesis of this study and also were asked to give feedback without subject identification.

The frequency and influence of “fat talk” were assessed at baseline using the following items, “What do you think of your body image?”, “How often do you ‘fat talk’ with friends?”, “How do you feel after ‘fat talk’?”, “How do you perceive your body after ‘fat talk’?”, and “How do you perceive yourself after ‘fat talk’?”

Body satisfaction and self-esteem were assessed at baseline, post-intervention and at 1-month follow-up. The primary outcome measured was body satisfaction, assessed using the Body Esteem Scale for Adults and Adolescents (BES) [40]. The secondary outcome measured was self-esteem, assessed using the Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPPC) [41].

The feasibility and acceptability of the program were assessed at the end of the program using two items with simple questions of “How useful did you find the program?” and “How much did you enjoy the program?”

SCOFF questionnaire [39]

The SCOFF questionnaire is a simple 5-item questionnaire with yes/no responses, and it was used to screen for possible cases of eating disorders. A score of ≥2 indicates a likely case of an eating disorder [39].

The SCOFF questionnaire was designed as a preliminary screening tool. A recent study with a multi-ethnic general population sample of adults in the UK found low sensitivity (53.7%) for the scale [42], but other studies showed better screening performance in adolescent populations [43, 44]. In this study, all participants who scored ≥2 were considered as SCOFF positive (SCOFF+) and at risk for an eating disorder while the rest were coded as SCOFF negative (SCOFF−).

Body esteem scale for adults and adolescents (BES) [40]

A 23-item self-report questionnaire with a 4-point Likert scale was used to measure participants’ body esteem. The total scores ranged from 23 to 92, with a higher score suggesting a higher level of body esteem. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of Korean adolescents was 0.83 in a previous study [45] and was 0.78 for this sample.

Self-perception profile for children (SPPC) [41]

A 20-item self-report questionnaire with a 5-point Likert scale was used to measure participants’ self-esteem. The total scores ranged from 20 to 100, with a higher score suggesting a higher level of self-esteem. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for Korean elementary school students was 0.91 in a previous study [46] and was 0.93 for this sample.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive data are presented as mean plus standard deviation for continuous outcomes and as frequency and percentage for categorical outcomes. The results of screening for eating disorders and frequency of “fat talk” were compared across genders using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. The main outcome variables (body esteem and self-esteem) were analyzed with 2 (gender: girls, boys) × 3 (times: baseline, post-intervention, follow-up) two-way repeated measures ANOVA to determine possible differences across baseline, post-intervention, and follow-up by gender. The effect size (Cohen’s d) for continuous outcomes was calculated by computing differences in the adjusted means between the pre- and post-intervention. Because Me, You and Us was developed with a focus on “fat talk,” we analyzed how much of an effect baseline “fat talk” had on the intervention outcome using the Pearson’s correlation analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Demographic characteristics of participants

The characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 12.30 ± 0.28, and their mean BMI was 19.61 ± 3.06 kg/m2. Baseline BMI percentiles did not significantly differ between boys and girls with both groups scoring at approximately the 50th percentile for sex and age. Compared to boys, girls showed lower body satisfaction (t = 4.117, df = 167, p < 0.001) and lower self-esteem (t = 4.755, df = 167, p < 0.001) at baseline. The percentage of students who had possible symptoms of eating disorders measured by SCOFF (SCOFF ≥ 2) was 15.4% (n = 26) and was significantly higher in girls (n = 19, 22.1%) than in boys (n = 7, 8.4%) [χ 2(1) = 9.129, p = 0.003] (Table 1).

Self-perception of fatness and the effect of “fat talk” of participants

The self-perception of fatness is presented as a bar graph in Fig. 2. The percentage of students feeling fat did not differ by gender [χ 2(2) = 4.587, p = 0.101], with 58 (34.9%) students feeling fat, 25 (15.1%) feeling thin, and 83 (50%) feeling like they were in normal shape (Fig. 2).

The percentage of participants engaging in “fat talk,” or negative commentary about weight and shape, are presented in Fig. 3. “Fat talk” frequency of more than once a week was higher in girls (n = 54, 62.8%) than in boys (n = 23, 27.7%) [χ 2(3) = 21.373, p < 0.001] (Fig. 3a). There was no difference between genders in their feelings after “fat talk” [χ2(2) = 1.838, p = 0.399] (32 (19%) participants responded that they felt worse, 5 (3%) participants responded that they felt better, and 131 (78%) reported no change) (Fig. 3b). Meanwhile, a gender difference was found in self-perception of body after a “fat talk” [χ 2(2) = 20.290, p < 0.001]; 42 girls (48.8%) and 15 boys (18.1%) responded that it led to them feeling dissatisfied with their body (Fig. 3c). Similarly, body self-confidence after “fat talk” differed by gender [χ 2(2) = 9.218, p = 0.027] with 18 girls (20.9%) and 6 boys (7.3%) responding that they felt less confident in themselves (Fig. 3d).

Impact of intervention on body satisfaction and self-confidence

Table 2 shows the impact of intervention by gender on body satisfaction (Fig. 4) and self-esteem (Fig. 5). The two-way repeated measures ANOVA between intervention and gender on body satisfaction revealed effects of intervention [F(2,157) = 3.097, p = 0.048 η 2 = 0.038] and gender [F(1,158) = 11.764, p = 0.001 η 2 = 0.069] and an interaction effect [F(2,157) = 3.082, p = 0.049, η 2 = 0.038], (Table 2; Fig. 4). In the following simple main effect analysis for investigating the interaction effect, girls showed significant change in their body satisfaction [F(2,79) = 9.170, p = 0.003, η 2 = 0.104]. In girls, the paired comparison with Bonferroni correction revealed that body satisfaction increased significantly with a moderate effect after the intervention (t = 2.824, df = 83, p = 0.006, d = 0.258), and this was maintained at 1-month follow-up. In boys, the simple main effect analysis showed no changes in their body satisfaction in the time interval for measurement [F(2,79) = 0.094, p = 0.760, η 2 = 0.001].

Impact of intervention on body satisfaction measured at baseline, post-intervention, and at follow-up by gender. The two-way ANOVA between intervention and gender revealed the effect of intervention [F(2,157) = 3.097, p = 0.048, η 2 = 0.038] and the interaction effect [F(2,157) = 3.082, p = 0.049, η 2 = 0.038]. BES body esteem scales for adults and adolescents

Impact of intervention on self-esteem measured at baseline, post-intervention, and at follow-up by gender. The two-way ANOVA between intervention and gender on self-esteem revealed the effect of intervention [F(2,156) = 4.679, p = 0.011, η 2 = 0.057], but no interaction effect [F(2,156) = 0.396, p = 0.647, η 2 = 0.005]. SPPC self-perception profile for children

The two-way repeated measures ANOVA between intervention and gender on self-esteem revealed effects of intervention [F(2,156) = 4.679, p = 0.011, η 2 = 0.057] and gender [F(1,157) = 21.896, p < 0.001 η 2 = 0.122], but no interaction was observed [F(2,156) = 0.396, p = 0.647, η 2 = 0.005] (Table 2; Fig. 5). The paired comparison with Bonferroni correction revealed that self-esteem increased significantly at post-intervention (t = 2.595, df = 162, p = 0.010, d = 0.167), but this increase was not maintained at the 1-month follow-up.

Subsidiary analysis of the impact of the intervention by SCOFF+ or SCOFF−

Table 3 shows the effect of body satisfaction and self-esteem by SCOFF. Subjects who screened positive for symptoms of eating disorders (SCOFF ≥ 2) at baseline had an increase in body satisfaction both at post-intervention and at follow-up, whereas there was less change in the residual group (t = 4.119, df = 161, p < 0.001, d = 0.895 at post-intervention; t = 2.566, p = 0.011, df = 161, d = 0.789 at follow-up) (Table 3). The differences in self-esteem between SCOFF+ and SCOFF− participants were significant at follow-up (t = 1.612, df = 161, p = 0.109, d = 0.350 at post-intervention; t = 2.248, df = 161, p = 0.026, d = 0.496 at follow-up). Thus, the high risk group for eating disorders gained more benefit from the program in their body satisfaction and self-esteem.

Factors correlated with the impact of the intervention

In a correlation analysis to find factors related to the impact of the intervention, the frequency of “fat talk” was correlated with the impact of the intervention on body satisfaction (r = 0.325, p < 0.001). There was no relation between frequency of “fat talk” and impact of the intervention on self-esteem (r = 0.120, p = 0.130).

Feasibility and acceptability of the intervention

98.8% of participants felt either neutral or positive about the usefulness of the intervention. 93.7% of boys and 77.4% of girls responded that they enjoyed the program. The acceptability of the program is presented in Fig. 6.

The results of the participants’ feedback of the program are presented in Table 4. Most participants reported that the program provided appropriate information regarding eating disorders and stimulated awareness of eating disorders. Negative opinions included demands for more audio–visual materials and more reciprocal interaction between the instructors and participants.

Discussion

This study examined the feasibility and acceptability of an adaptation of an eating disorder prevention program, Me, You and Us, for young adolescents in Korea. The 6-week program was associated with an improvement in body satisfaction and self-esteem, particularly in girls and those screened at high risk for eating disorders. The participants with higher frequency of “fat talk” had more improvement in body satisfaction from the intervention. Improved body esteem in girls was maintained, but general self-esteem returned to baseline at the 1-month follow-up. This intervention was unique that it included a positive psychological approach in its lessons to tackle depression and low self-esteem as well as targeting “fat talk”.

Girls had lower baseline body and self-esteem than boys in Korea, which is consistent with previous reports from North America [47,48,49]. These gender differences may be attributed to many factors including girls’ hormonal and physical changes at this stage in puberty, which result in a greater proportion of body fat in adult females compared to adult males. We found that “fat talk” was common in 6th grade students at an elementary school; 63% of the girls engaged in this more than once a week. Following “fat talk,” 50% of the girls were left feeling dissatisfied with their body, and 20% had a decrease in self-esteem.

15.4% of students were screened as SCOFF+ with possible symptoms of eating disorders (22.1% in girls and 8.4% in boys). This result is slightly lower than those of other studies in European adolescents of an older age, e.g., 21.7% of Spanish adolescents were screened as SCOFF+ in 2016 (28.1% in girls and 11.2% in boys with mean ages of 14.9) [50], and 21.9% of German adolescents were screened as SCOFF+ in 2006 (aged 11–17 years) [51].

The finding that the effectiveness of the program was higher in those with possible pre-clinical symptoms is in accordance with the literature where greater improvements in body image and other secondary factors were reported with high risk groups [15, 52, 53]. In the previous study by Sharpe et al., patients with eating disorders were excluded, which might explain the larger effect of our intervention than what was seen in girls at post-intervention in the UK. However, as the group with SCOFF+ was small in our study, these findings need to be replicated.

The design of the study differed from the original Me, You and Us study by Sharpe et al. by a few points. The students were slightly younger (mean age of 12.3 years) in this study than in the UK (mean age of 13.1 years). Also, we recruited both girls and boys to this study as the majority of elementary schools are mixed-gender environment. We found that the Me, You and Us program was acceptable to boys. This suggests that the program may be used to provide a positive and powerful influence in a mixed-gender environment. Teachers delivered the intervention in the UK, whereas social workers with no prior knowledge of eating disorders or body image interventions but with a 6-h training session delivered the course in Korea. The issue about how to best disseminate these interventions remains uncertain [22, 54,55,56].

The limitations of this study should be noted. One was the absence of a control group. Thus, the effects of the program may be partly influenced by developmental effects, although this is unlikely since other studies have found increasing body dissatisfaction over time [57]. Furthermore, there may have been “regression to the mean” within subjects whereby those with a more severe form of an eating disorder score lower on body satisfaction or self-esteem over repeated measurements. This effect could be corrected statistically through a mixed effect model with a control group. The other limitation was the absence of measurements for eating pathology, appearance conversation, peer support, or depressive symptoms either before or after intervention, in an effort to minimize subject burden in the study.

In conclusion, we suggest that the program Me, You and Us can play a role in increasing body satisfaction and self-esteem by reducing “fat talk” in 6th grade students in Korea. This study demonstrated that the intervention is acceptable and adaptable for young Korean adolescents.

References

Currin L, Schmidt U, Treasure J, Jick H (2005) Time trends in eating disorder incidence. Br J Psychiatry 186:132–135. doi:10.1192/bjp.186.2.132

Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC (2007) The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry 61:348–358. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

Keski-Rahkonen A, Hoek HW, Susser ES, Linna MS, Sihvola E, Raevuori A, Bulik CM, Kaprio J, Rissanen A (2007) Epidemiology and course of anorexia nervosa in the community. Am J Psychiatry 164:1259–1265. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06081388

Micali N, De Stavola B, Ploubidis G, Simonoff E, Treasure J, Field AE (2015) Adolescent eating disorder behaviours and cognitions: gender-specific effects of child, maternal and family risk factors. Br J Psychiatry 207:320–327. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.114.152371

Stice E (2002) Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 128:825–848. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.128.5.825

Taylor CB, Bryson SW, Altman TM, Abascal L, Celio A, Cunning D, Killen JD, Shisslak CM, Crago M, Ranger-Moore J, Cook P, Ruble A, Olmsted ME, Kraemer HC, Smolak L, McKnight I (2003) Risk factors for the onset of eating disorders in adolescent girls: results of the McKnight longitudinal risk factor study. Am J Psychiatry 160:248–254. doi:10.1176/ajp.160.2.248

Stice E, Becker CB, Yokum S (2013) Eating disorder prevention: current evidence-base and future directions. Int J Eat Disord 46:478–485. doi:10.1002/eat.22105

Austin SB (2016) Accelerating progress in eating disorders prevention: a call for policy translation research and training. Eat Disord 24:6–19. doi:10.1080/10640266.2015.1034056

Neumark-Sztainer D, Levine M, Paxton S, Smolak L, Piran N, Wertheim E (2006) Prevention of body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: What’s next? Eat Disord 14:265–285. doi:10.1080/10640260600796184

O’Dea J, Maloney D (2000) Preventing eating and body image problems in children and adolescents using the health promoting schools framework. J Sch Health 70:18–21

Smolak L, Levine MP, Schermer F (1998) A controlled evaluation of an elementary school primary prevention program for eating problems. J Psychosom Res 44:339–353. doi:10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00259-6

Neumark-Sztainer DR, Friend SE, Flattum CF, Hannan PJ, Story MT, Bauer KW, Feldman SB, Petrich CA (2010) New moves-preventing weight-related problems in adolescent girls a group-randomized study. Am J Prev Med 39:421–432. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2010.07.017

Stice E, Rohde P, Shaw H, Gau J (2011) An effectiveness trial of a selected dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program for female high school students: long-term effects. J Consult Clin Psychol 79:500–508. doi:10.1037/a0024351

Wilksch SM, Paxton SJ, Byrne SM, Austin SB, McLean SA, Thompson KM, Dorairaj K, Wade TD (2015) Prevention across the spectrum: a randomized controlled trial of three programs to reduce risk factors for both eating disorders and obesity. Psychol Med 45:1811–1823. doi:10.1017/s003329171400289x

O’Dea JA, Abraham S (2000) Improving the body image, eating attitudes, and behaviors of young male and female adolescents: a new educational approach that focuses on self-esteem. Int J Eat Disord 28:43–57

Richardson SM, Paxton SJ (2010) An evaluation of a body image intervention based on risk factors for body dissatisfaction: a controlled study with adolescent girls. Int J Eat Disord 43:112–122. doi:10.1002/eat.20682

Richardson SM, Paxton SJ, Thomson JS (2009) Is body think an efficacious body image and self-esteem program? A controlled evaluation with adolescents. Body Image 6:75–82. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.11.001

Stanford J, McCabe MP (2005) Sociocultural influences on adolescent boys’ body image and body change strategies. Body Image 2:105–113. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.03.002

Stewart DA, Carter JC, Drinkwater J, Hainsworth J, Fairburn CG (2001) Modification of eating attitudes and behavior in adolescent girls: a controlled study. Int J Eat Disord 29:107–118

Wade TD, Davidson S, O’Dea JA (2003) A preliminary controlled evaluation of a school-based media literacy program and self-esteem program for reducing eating disorder risk factors. Int J Eat Disord 33:371–383. doi:10.1002/eat.10136

Wilksch SM, Wade TD (2009) Reduction of shape and weight concern in young adolescents: a 30-month controlled evaluation of a media literacy program. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48:652–661. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181a1f559

Yager Z, Diedrichs PC, Ricciardelli LA, Halliwell E (2013) What works in secondary schools? A systematic review of classroom-based body image programs. Body Image 10:271–281. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.04.001

Nichter M (2001) Fat talk: what girls and their parents say about dieting. Harvard University, Cambridge

Cruwys T, Leverington CT, Sheldon AM (2016) An experimental investigation of the consequences and social functions of fat talk in friendship groups. Int J Eat Disord 49:84–91. doi:10.1002/eat.22446

Stice E, Maxfield J, Wells T (2003) Adverse effects of social pressure to be thin on young women: an experimental investigation of the effects of “fat talk”. Int J Eat Disord 34:108–117. doi:10.1002/eat.10171

Sharpe H, Schober I, Treasure J, Schmidt U (2013) Feasibility, acceptability and efficacy of a school-based prevention programme for eating disorders: cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 203:428–435. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.113.128199

McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA (2004) Body image dissatisfaction among males across the lifespan—a review of past literature. J Psychosom Res 56:675–685. doi:10.1016/s0022-3999(03)00129-6

Levine MP, Smolak L (2006) The prevention of eating problems and eating disorders: theory, research, and practice. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah

Neumark-Sztainer D, Paxton SJ, Hannan PJ, Haines J, Story M (2006) Does body satisfaction matter? Five-year longitudinal associations between body satisfaction and health behaviors in adolescent females and males. J Adolesc Health 39:244–251. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.001

O’Dea JA (2004) Evidence for a self-esteem approach in the prevention of body image and eating problems among children and adolescents. Eat Disord 12:225–239. doi:10.1080/10640260490481438

Thomas JJ, Lee S, Becker AE (2016) Updates in the epidemiology of eating disorders in Asia and the Pacific. Curr Opin Psychiatry 29:354–362. doi:10.1097/yco.0000000000000288

Jung J, Forbes GB (2007) Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating among college women in China, South Korea, and the United States: contrasting predictions from sociocultural and feminist theories. Psychol Women Q 31:381–393. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00387.x

Cho JH, Han SN, Kim JH, Lee HM (2012) Body image distortion in fifth and sixth grade students may lead to stress, depression, and undesirable dieting behavior. Nutr Res Pract 6:175–181. doi:10.4162/nrp.2012.6.2.175

Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. http://www.knhanes.cdc.go.kr. Accessed May 2017

Kim KA (2003) A relationship among appearance satisfaction, body cathexis and psychological characteristics during childhood and adolescence. Thesis of Master’s Degree in Graduate School of Sungshin Women’s University, Seoul, pp 31–41

Park JH, Choi TS (2008) The effect of body image on self-esteem in adolescents. Korean J Play Ther 11:117–129

Kim YR, Heo SY, Kang H, Song KJ, Treasure J (2010) Childhood risk factors in Korean Women with anorexia nervosa: two sets of case-control studies with retrospective comparisons. Int J Eat Disord 43:589–595. doi:10.1002/eat.20752

Chisuwa N, O’Dea JA (2010) Body image and eating disorders amongst Japanese adolescents. A review of the literature. Appetite 54:5–15. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2009.11.008

Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH (1999) The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. Br Med J 319:1467–1468

Mendelson BK, White DR (1985) Development of self-body-esteem in overweight youngters. Dev Psychol 21:90–96

Harter S (1981) The perceived competence scale for children. Child Dev Psychol 53:87–97

Solmi F, Hatch SL, Hotopf M, Treasure J, Micali N (2015) Validation of the SCOFF questionnaire for eating disorders in a multiethnic general population sample. Int J Eat Disord 48:312–316. doi:10.1002/eat.22373

Luck AJ, Morgan JF, Reid F, O’Brien A, Brunton J, Price C, Perry L, Lacey JH (2002) The SCOFF questionnaire and clinical interview for eating disorders in general practice: comparative study. Br Med J 325:755–756. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7367.755

Parker SC, Lyons J, Bonner J (2005) Eating disorders in graduate students: exploring the SCOFF questionnaire as a simple screening tool. J Am Coll Health 54:103–107. doi:10.3200/jach.54.2.103-107

Lee JS (2001) Correlation among adolescents gender, obesity, others appraisal of their bodies and the adolescents body-esteem. Korea National University of Education, Cheongju

Lee HY (2004) Correlation between their body image and self-esteem dependent on the degree of obesity of obese children. Univ. of Kong Ju, Gongju

Dion J, Hains J, Vachon P, Plouffe J, Laberge L, Perron M, McDuff P, Kalinova E, Leone M (2016) Correlates of body dissatisfaction in children. J Pediatr Psychol 171:202–207. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.12.045

Nelson TD, Jensen CD, Steele RG (2011) Weight-related criticism and self-perceptions among preadolescents. J Pediatr Psychol 36:106–115. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsq047

Xanthopoulos MS, Borradaile KE, Hayes S, Sherman S, Vander Veur S, Grundy KM et al (2011) The impact of weight, sex, and race/ethnicity on body dissatisfaction among urban children. Body Image 8:385–389. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.04.011

Querol SE, Alvira JMF, Graffe MIM, Rebato EN, Sanchez AM, Aznar LAM (2016) Nutrient intake in Spanish adolescents SCOFF high-scorers: the AVENA study. Eat Weight Disord 21:589–596. doi:10.1007/s40519-016-0282-8

Holling H, Schlack R (2007) Eating disorders in children and adolescents. First results of the German health interview and examination survey for children and adolescents (KiGGS). Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 50:794–799. doi:10.1007/s00103-007-0242-6

McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA, Karantzas G (2010) Impact of a healthy body image program among adolescent boys on body image, negative affect, and body change strategies. Body Image 7:117–123. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.10.007

Weiss K, Wertheim E (2005) An evaluation of a prevention program for disordered eating in adolescent girls: examining responses of high and low risk girls. Eat Disord 13:143–156. doi:10.1080/10640260590918946

Becker CB, Bull S, Schaumberg K, Cauble A, Franco A (2008) Effectiveness of peer-led eating disorders prevention: a replication trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 76:347–354. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.76.2.347

Flay BR, Biglan A, Boruch RF, Castro FG, Gottfredson D, Kellam S, Moscicki EK, Schinke S, Valentine JC, Ji P (2005) Standards of evidence: criteria for efficacy, effectiveness and dissemination. Prev Sci 6:151–175. doi:10.1007/s11121-005-5553-y

Marchand E, Stice E, Rohde P, Becker CB (2011) Moving from efficacy to effectiveness trials in prevention research. Behav Res Ther 49:32–41. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.10.008

Ricciardelli LA, McCabe MP (2001) Children’s body image concerns and eating disturbance: a review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev 21:325–344

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Helen Sharpe for offering the materials of Me, You and Us.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding sources

Financial support for this study was provided by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) with a Grant funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (Grant #. NRF-2014S1A5B8063466). The funding sources had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical measure.

Informed consent

Informed consents were received from a parent or a guardian for each of the participants.

Additional information

Gi Young Lee and Eun Jin Park are co-first authors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, G.Y., Park, E.J., Kim, YR. et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a prevention program for eating disorders (Me, You and Us) adapted for young adolescents in Korea. Eat Weight Disord 23, 673–683 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0436-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0436-3