Abstract

Purpose

This study aims to analyze and compare the level of body dissatisfaction (BD) in different eating disorders (ED) subtypes. Also, the relationship between BD and certain aesthetic body shape model influence and psychological variables was analyzed.

Methods

The sample consisted of 204 adolescent patients, who were attending in an ED Unit in Zaragoza (Spain). The following instruments were applied: the Spanish Children’s Depression Questionnaire (CEDI-II), the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES), the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-40), the Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ-34) and the Questionnaire of Influences of Aesthetic Body shape Model (CIMEC-40).

Results

The group of Bulimia Nervosa (BN) showed the greatest BD. Those patients who showed higher levels of BD had lower self-esteem, more depressive symptoms, a greater presence of disordered eating attitudes, and more influence of the aesthetic body shape model.

Conclusions

This study contributes to highlight the idea of implementing effective prevention programs and specific interventions related to BD in the treatment of ED.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Considering body image disturbances, adolescence is the most vulnerable life stage because it is a period characterized by physiological, emotional, cognitive and, above all, social changes. As a result, there is a greater concern for physical appearance [1]. During adolescence, the body is experienced as a source of identity, self-concept and self-esteem. Some psychosocial facets of adolescence are a high tendency to introspection and self-scrutiny, social comparisons, self-awareness related to physical image and social development [2].

Several studies have shown evidence of an increasing concern about body image among adolescents, this happening progressively in earlier ages [3–6]. As a result, BD is very frequent [7], affecting their normal development and wellbeing, thus leading to self-esteem problems [8], depressive symptoms [9] and risk for ED [10].

On the one hand, adolescence is one of the most critical periods to self-esteem development. Some studies, based on samples of adolescents, have reported that self-esteem is negatively related to body dissatisfaction [11, 12]; other studies state that self-esteem is a mediator between body dissatisfaction and restrictive eating [13, 14].

On the other hand, Stice and Bearman [15] have proposed a theoretical model in which body dissatisfaction would have a role as predictor of depression in adolescents. These authors state that specific changes of puberty in adolescent girls cause a gap between their body image and the prevalent ideal of thinness in our culture. Thus, these changes trigger BD and BD increases depressive symptoms. At the same time, depression is considered as a negative factor on the weight, increasing the risk for BD and concerns related to eating [16–18].

Up to now, studies emphasize the importance of knowing and analyzing the variables involved in BD, how it is originated, what factors precipitate BD and how it is related to other variables [19]. Also, due to the relevant role of BD in the genesis, development and recovery of ED [20, 21], this variable is considered the most relevant in the current study, since it seems imperative to intervene on the acceptance of body image during the ED treatment.

It must be taken into account that sociocultural environment, as different authors have reported, influences the development of personality and self-esteem and, therefore, body satisfaction. In this field of study, authors such as Harrison [22], Sung-Yeon [23] or Rajagopalan and Shejwal [24] have noted that sociocultural pressure is a relevant factor, which exerts great influence on body perception. Also, Homan [25] postulated that the thin-ideal internalization directly promotes BD-related behaviors increasing the tendency to control diet and weight.

Otherwise, there is a shortage of research comparing the level of BD in adolescents according to different diagnostic categories of ED due to the fact that most studies have focused on adult populations [26]. Ruuska et al. [27] studied the BD differences, along with other variables, in a group of patients diagnosed with AN and BN, aged 14–21, and they concluded that the BN group showed higher levels of BD than the AN group. They highlighted that the construct “body dissatisfaction” should be taken into account in the assessment and therapeutic interventions for ED. Also, the meta-analysis conducted by Cash and Deagle [28] on 66 studies published between 1974 and 1993, revealed that the BN group had higher levels of BD compared with AN patients. Similar results appear in a meta-analytical study on the nature of the body image disturbances associated with ED, by Sepulveda et al. [29], on 83 independent primary studies published between 1970 and 1998. In this study, bulimic patients achieved higher scores on BD comparing with other ED patients.

Considering the relevance that the current literature gives to the concept of BD, and bearing in mind the few studies comparing this construct in different diagnostic categories of ED in samples of adolescents, the objectives and hypotheses of this study were: (1) to establish the relationship between BD and the following variables: self-esteem, depression, presence of abnormal eating behavior and influence of the aesthetic body shape model (the assumption being that the BD is negatively related to self-esteem, and positively with depression, presence of abnormal eating behaviors and influence of the aesthetic body shape model); and (2) to compare BD in different subgroups of ED (the hypothesis being that patients with BN have higher BD than other ED patients).

Method

Participants

In the present study, data of patients who were referred over a period of 6 consecutive years (2008–2013) to child and adolescent ED Unit (EDU) of University Hospital Lozano Blesa (Zaragoza) were collected. It must be noted that this EDU is the reference Unit in Aragon (Spain) and, therefore, where all patients belonging to this geographic area are referred to.

For methodological reasons and aiming to make the sample homogeneous, the following inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied: (1) meet DSM-5 criteria [30] for subgroups of ED: Anorexia Nervosa-restrictive type (AN-R), Anorexia Nervosa-binge/purging type (AN-P), Bulimia Nervosa (BN), Binge-Eating Disorder (BED) and Unspecified Feeding and Eating Disorder (EDNOS); and (2) age between 13 and 16 years old.

Following this procedure, a total sample of 204 patients was obtained: 72 of them diagnosed with AN-R (35.3%), 28 patients with AN-P (13.7%), 35 with BN (17.2%), 21 patients diagnosed of BED (10.3%) and 45 with EDNOS (23.5%). There were 10.3% boys (21/204) and 89.7% girls (183/204), all of them aged between 13 and 16 years old [mean age 14.91 (SD = 1.16)]. With respect to their residence, 35.8% came from rural areas and 64.2% from urban areas. Considering their education, 63.7% attended public schools and 36.3% concerted-private schools. Regarding the BMI categories, 27.5% (56/204) had severe underweight, 31.9% (65/204) underweight, 27.9% (57/204) normal weight, 8.3% (17/204) overweight and 4.4% (9/204) obesity. The mean BMI was 20.27 (SD = 5.21).

Instruments

As demographic variables, sex, age (when first consultation), residence (rural–urban) and type of school (public and concerted-private) were considered. The specific diagnostics were AN-R, AN-P, BN, BED and EDNOS. On the other hand, the body mass index (BMI) of all subjects was assessed by a nurse who weighed and measured every single patient who attended the ED Unit. BMI was calculated according to standard procedures (weight—kg/height—m2). Height was measured using a wall-mounted stadiometer (Holtain, Dyfed, UK), to the nearest 0.5 cm, with the participant’s head in the Frankfort plane. Also, the following variables were measured by means of the corresponding instruments: the influence of the aesthetic body shape model (CIMEC-40), self-esteem (Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale), depressive symptoms (CEDI-II), BD (BSQ-34) and abnormal eating behaviors (EAT-40).

Children Depression Spanish Questionnaire (CEDI-II) by Rodríguez-Sacristán et al. [31]; Spanish adaptation of the Kovacs’s Children Depression Inventory (CDI) [32]. This questionnaire rates depressive symptoms (sadness, pessimism, low self-esteem, high self-criticism, feelings of guilt, insecurity, worry, feelings of loneliness, indecision, apathy, mood, irritability, sense of failure and rebellion) in childhood and adolescence. The questionnaire has an internal consistency from 0.71 to 0.89 (total) and 0.59 to 0.68 (factors); it has good predictive validity and it is useful to detect the effectiveness of treatment.

Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) [33] adapted for Spanish population by Vázquez et al. [34]. This is one of the most used scales to measure the global self-esteem in adolescents and it includes items focusing on feelings of respect and acceptance of oneself. The Spanish adaptation for clinical populations has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = 0.87) and adequate test–retest reliability (for 2 months, r = 0.72 and for a year, r = 0.74).

Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-40) by Garner and Garfinkel [35]; Spanish version of Castro, Toro and Salamero [36]. It is an instrument designed to detect the presence of abnormal eating attitudes, especially those related to the fear of gaining weight, drive for thinness and restrictive eating patterns. It evaluates psychological and/or behavioral characteristics associated with ED, grouped into three subscales: diet, bulimia and food concerns, and oral control [37]. The reliability of this instrument is adequate with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79 in clinical samples and 0.94 in mixed samples—clinical and control participants [38].

Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ-34) by Cooper et al. [39]. The Spanish version of Raich et al. [40] was used, which has acceptable psychometric guarantees. It is a self-reported questionnaire designed to measure BD, fear of gaining weight, physical appearance-related self-devaluation, specific desires to lose weight and the avoidance of those situations where physical appearance would attract the attention of others. The BSQ-34 comprises four subscales (BD, fear of gaining weight, appearance-related low esteem and desire to lose weight) and consists of 34 items that are answered by a standard six-point Likert scale ranging from “never” to “always”. The total score ranges between 34 and 204. The cut-off point is usually established at 105; higher scores indicate higher BD. The reliability of this questionnaire has been reported with high levels of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95–0.97).

Questionnaire of Influences of the Aesthetic Body Shape Model (CIMEC-40) by Toro et al. [41]. In Spanish samples, it presents adequate psychometric properties. It is a self-reported instrument to assess the individual’s perceived pressure for weight loss related to the media and the immediate social environment. It evaluates five areas or problems: body image concerns, influence of advertising, influence of verbal messages, influence of social models and influence of social situations. In Spanish samples, it presents an adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93), the sensitivity and specificity being 81.4 and 55.9%, respectively.

Procedure

To collect the data from this study, medical records of all participants were used. Anonymity was maintained. Patients were referred to the EDU from primary care or from the specialized outpatient section of child and adolescent psychiatry at University Hospital Lozano Blesa in Zaragoza (Spain) after an initial psychiatric assessment to check the risk or the existence of specific eating psychopathology. Once in the EDU, a first diagnostic interview (psychiatry, clinical psychology and nursing) was performed. Then, a psychometric evaluation was carried out in which clinical, personality, intelligence, adaptation and food data were obtained. From this set of psychometric data, those appropriate for this research, along with the already mentioned sociodemographic variables, were collected.

Results

Data were analyzed with the SPSS statistical package for Windows (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), version 19. First of all, a descriptive and exploratory analysis of the results of the questionnaire BSQ-34, in each diagnostic group, was conducted. To carry out that descriptive analysis, the BSQ-34 scores were categorized considering the cut-off point (>105). A significant relationship was observed between the diagnosis and body dissatisfaction (\(X_{(8)}^{2}\) = 23.167; p < .005). As it is shown in Table 1, in 35 cases, there were no valid measures for all the variables included in this study; so, in this sample, 17.2% are considered as missing values. Taking into account the rest of the sample, 49% of patients were satisfied with their body image, while 33.3% showed body dissatisfaction. Among the group of patients without body dissatisfaction, the subgroup AN-R represented 23.5%, the AN-P 5.4%, the BN 3.4%, the BED 5.4% and EDNOS 11.8%. Moreover, within the group of patients with body dissatisfaction, the subgroup AN-R represented 6.9%, the AN-P 6.4%, the BN 8.3%, the BED 3.4% and EDNOS 8.3%. Therefore, considering the total sample, BN and EDNOS subgroups presented 8.3% and 8.3% of the dissatisfaction group, respectively, followed by the AN-R (6.9%), with the BED subgroup manifesting the lowest percentage of body dissatisfaction (3.4%).

Following Cooper and Taylor [42] and taking into account the total scores, four categories were established with respect to body image concerns: no concern (score <80), mild (score between 81 and 110), moderate (score between 111 and 140) and extreme concern (score >141 points). A significant relationship between the diagnostic groups and these categories of BSQ-34 was found (\(X_{(16)}^{2}\) = 44.585 p < .005). As it is shown in Table 2, 38.7% of the sample was not concerned about their body image, 14.7% had a slight concern, 24.5% moderate and 4.9% showed extreme concern. Referring to the no-concern group, the AN-R represented 19.1%, the AN-P 2%, BN 2.9%, BED 4.4% and EDNOS 10.3%. Among those patients with mild concern, the subgroup AN-R represented 5.9%, the AN-P 3.9%, the BN 1%, the BED 2% and EDNOS 2%. In the group of patients showing a moderate concern, AN-R represented 4.9%, AN-P 3.9%, BN 1%, BED 2% and EDNOS 7.8%. Finally, among patients who exhibited an extreme concern with their body image, the percentages were 0.5% (AN-R), 1.5% (AN-P), 2.5% (BN), 0.5% (BED) and 0% (EDNOS).

An analysis of the relationship between the BD (BSQ-34) and self-esteem (RSES), depressive symptoms (CEDI-II), the presence of abnormal eating behaviors (EAT-40), and the influence of the aesthetic body shape model (CIMEC-40) was performed.

Since not all variables fitted a normal distribution, the bivariate correlations by means of Spearman’s rho coefficient were explored. The results showed positive associations between BD and depressive symptoms (ρ = .633; p < .001); abnormal eating behaviors (ρ = .720; p < .001); and influence of aesthetic body shape model (ρ = .796; p < .001). The BD was negatively related to self-esteem (ρ = −.308; p < .005).

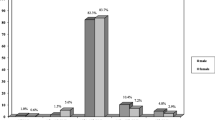

Possible BD differences (BSQ-34) in the subgroups of ED were analyzed. A one-way ANOVA was performed which showed significant differences between the diagnostic subgroups (F (4) = 7.726; p < .001). The diagnostic categories of BN (M = 111.79, SD = 31.41) and AN-P (M = 106.46, SD = 29.59) showed the highest rates in body dissatisfaction compared to the other diagnostic categories (Fig. 1).

The Levene’s test (W (4; 163) = 4.847, p < .001) indicated that the homoscedasticity criterion was not met; so, the Welch’s t test (unequal variance t test) was considered (t (4;63,29) = 10.156; p < .001), revealing the existence of significant differences among the groups. As a result, the post hoc Games–Howell test was performed to determine between which pairs of groups that the means differed (the Games–Howell test is used with unequal variances and also takes into account unequal group sizes). The AN-R group differed significantly from the groups AN-P (p < .001) and BN (p < . 001). The AN-P group had differences with AN-R (p < .001) and EDNOS (p < .05). The BN group showed differences with respect to AN-R (p < .001) and EDNOS (p < .01), and finally, the EDNOS group differed from the BN group (p < .01).

These results confirm that groups with purgative characteristics such as BN (M = 111.79, SD = 31.41) and AN-P (M = 106.46, SD = 29.59) have more BD than the other diagnostic categories: BED (M = 83.94, SD = 42.19), EDNOS (M = 74.27, SD = 49.04) and AN-R (M = 66.41, SD = 42.84), in all cases with statistically significant differences (p < .05).

Discussion

This study has as one of its main objectives to explore the relationship between BD and certain aesthetic body shape model influence and psychological variables. First of all, our results highlight the significant and positive correlation between BD and depression. Patients showing more BD have more depressive symptoms such as sadness, apathy, guilt and feelings of personal failure, among others. This result is in accordance with previous ones [18, 43].

Next, we also found a significant and negative correlation between BD and self-esteem. Apparently, physical appearance and the concept we have about this construct play an important role during adolescence [44]. The results allow us to support the initial hypothesis in the line of other previous studies [11, 45], suggesting that a poor body image is usually associated with low self-esteem. Studies confirm that at least one-third of the self-esteem is linked to positive or negative self-image. It could be said that if a person does not like his/her body, it is difficult to live in it. It is also very difficult to appreciate personal qualities as dexterity, intelligence or work regardless of his/her body appreciation, especially in women, who usually subordinate many of these qualities to the physical appeal [46].

Another finding in this study, according to the Homan’s results [23], is that BD is directly related to sociocultural influences that contribute to the internalization of the current aesthetic body shape model (extreme thinness). This fact highlights the importance of pressure to lose weight from media and the immediate social environment. In this context, media are very important factors to transmit and empower messages about the desire of thinness. These media along with the immediate social context transmit the social pressure to be thin, thus being an influential variable in the development of ED [47, 48].

Finally, there is a significant and positive relationship between BD and eating-related psychopathology. Our data show consistency with the results of other authors such as Stice and Shaw [49]. Therefore, based on these findings, patients who show higher BD usually have more abnormal eating attitudes, especially those related to the fear of gaining weight, drive for thinness and restrictive eating patterns [50]. That is why our research identifies BD as one of the most consistent risk factors for developing an ED.

Another objective of this study was to compare BD among the different diagnostic categories of ED in a sample of adolescents. In this regard, significant differences among subgroups of ED have been found, the BN group being the one with the highest values in this construct. The hypothesis gained support from these results confirming the meta-analysis conducted by Cash and Deagle [28] and Sepulveda et al. [29] as well as the study of Ruuska et al. [27] in a sample of adolescents. All of them also found a higher value in the BN group. The second group with the highest body dissatisfaction was the AN-P group. Therefore, it appears that subjects exhibiting purging behavior are the most dissatisfied with their body image. Some studies claim that patients with AN-P and BN have higher levels of psychopathology [51], and it seems that bulimic symptoms are associated with a worse course of ED [52].

Considering these results, it may be stated that the focus of primary prevention would be the acceptance of body image; specifically, it would be necessary to intervene to promote proper recognition, appreciation and acceptance of body image in children and adolescents; that would be a way to prevent behaviors such as going on unnecessary diet or, in extreme cases, the development of an ED during this developmental period. For these programs of prevention, interventions have to exceed individual consultations, due to the fact that the problem goes beyond the limits of clinical context, being a part of the field of society and culture; therefore, it would be important to involve families, schools, pediatricians and media, thus integrating the prevention of ED as a priority in the field of adolescents’ health problems [10]. Prevention programs should be focused on general population campaigns or on special risky groups (dancers, models, etc.). Traditionally, the prevention of such problems has been focused on the negative factors of behavior (traditional model of diseases), which has pointed to the prevention of risk factors [53]. Prevention programs developed under this psychological approach have aimed at different types of intervention. The best results (to improve body image and avoid eating problems) have been obtained by means of promoting a critical view of the media information [48], employing the technique of cognitive dissonance [54–57] and improving self-esteem [58]. To change this conception of disease, it is currently recommended to focus prevention programs on the perspective of “normality and health”, considering the role of protective factors in the prevention of negative body image in ED [59, 60]. The Health Psychology and the paradigm of Positive Psychology are the main sources to get a more comprehensive concept of health, and to implement more flexible and less default behaviors, thus helping the individual to develop more adaptive behavioral repertoires and, in general, a better performance [61]. Levine and Smolak [59] suggested that ED and body image specialist have turned their attention to positive body image, body acceptance, and other strengths.

In short, we believe that BD is a predisposing factor for ED that can be modified, since it is derived from a cognitive process of comparison, self-evaluation and orientation; therefore, a greater knowledge of this variable will allow us to establish preventive programs for premorbid populations.

This study has some limitations. It is a retrospective cross-sectional study; so, the results should be interpreted in this context. Despite only relations (but not causalities) have been found, we believe that body self-perception and the possible and consequent BD in adolescents constitute a key factor to develop ED.

Another aspect to be considered is that the clinical sample used belongs to a specific unit of ED, in which patients are derived solely from the community of Aragon (it has a population approximately 1.4 million). In this regards, for a generalization of the results, it would be adequate to replicate this research with clinical samples from other regions.

It must be noted that to measure BD, we have used a cognitive–affective method, the Body Shape Questionnaire—BSQ-34—[38] which reflects attitudinal and affective variables, and has a number of limitations. However, the meta-analysis by Sepulveda et al. [29] of 83 studies on the alteration of body image in ED showed that attitudinal measures of body image cause greater effect sizes than perceptual measures, and therefore, it might be thought that the attitudes and beliefs about oneself are those that show a closer association with dissatisfaction. Still, our results must be interpreted with caution until further research confirms them.

With respect to future lines of intervention in the field of BD, it would be particularly important to analyze this construct and its relationship with different variables in child population, since studies at these ages are still scarce [62]. Recent research indicates that even among young children, negative body image may be related to the use of weight-loss behaviors and with indicators of eating pathology [63]. It seems that this fact is increasing in progressively younger ages [3–6].

Another aspect to be considered is that methodological relationships between different variables and BD have been proven, but longitudinal studies are necessary to precisely establish what is the direction of these variables. Also, statistically significant BD indicators are needed.

We also consider that it is necessary to replicate this research in other cultures. Traditionally, BD has been confined exclusively to Western contexts or Westernized societies but over time and considering the phenomenon of globalization, it has been shown that these problems are a present element in almost all cultures [64].

Conclusions

-

1.

Those adolescents suffering from BN showed more severe BD than other ED patients.

-

2.

Patients with the worst body image reported lower self-esteem, more depressive symptoms and more presence of disturbed eating attitudes. Also, they were more influenced by the aesthetic body shape model.

-

3.

This study tries to propose the body image acceptance as the core of the primary prevention of ED, highlighting a specific intervention on ED, which focuses on BD.

References

Lawler M, Nixon E (2011) Body dissatisfaction among adolescents boys and girls: the effects of body mass, peer appearance culture and internalization of appearance ideals. J Youth Adolesc 40(1):59–71. doi:10.1007/s10964-009-9500-2

Helfert S, Warschburger P (2013) The face of appearance-related social pressure: gender, age and body mass variations in peer and parental pressure during adolescence. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 7:16. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-7-16

Bun CJ, Schwiebbe L, Schütz FN, Bijlsma-Schlösser JF, Hirasing RA (2012) Negative body image and weight loss behavior in Dutch school children. Eur J Public Health 22(1):130–133. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckr027

Davison TE, McCabe MP (2006) Adolescent body image and psychosocial functioning. J Soc Psychol 146(1):15–30. doi:10.3200/SOCP.146.1.15-30

Lee J, Lee Y (2016) The association of body image distortion with weight control behaviors, diet behaviors, physical activity, sadness, and suicidal ideation among Korean high school students: a cross-sectional study. BCM Public Health 16:39. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-2703-z

Rodgers RF, Paxton SJ, McLean SA (2014) A biopsychosocial model of body image concerns and disordered eating in early adolescents girls. J Youth Adolesc 43(5):814–823. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-0013-7

Espinoza P, Penelo E, Raich RM (2010) Disordered eating behaviors and body image in a longitudinal pilot study of adolescent girls: what happens 3 years later? Body Image 7:70–73. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.09.002

Jones DC, Newman JB (2009) Early adolescent adjustment and critical evaluations by self and other: the prospective impact of body image dissatisfaction and peer appearance teasing on global self-esteem. Eur J Dev Sci 3(1):17–26. doi:10.3233/DEV-2009-3104

Rosenström T, Jokela M, Hintsanen M, Josefsson K, Juonala M, Kivimäki M, Pulkki-Raback L, Viikari J, Hutri-Kähönen N, Heinonen E, Raitakari OT, Keltikangas-Järvinen L (2013) Body-image dissatisfaction is strongly associated with chronic dysphoria. J Affect Disord 150(2):253–260. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.003

Rohde P, Stice E, Marti CN (2015) Development and predictive effects of eating disorder risk factors during adolescence: implications for prevention efforts. Int J Eat Disord 48(2):187–198. doi:10.1002/eat.22270

Mäkinen M, Puuko-Viertomies LR, Lindberg N, Siimes MA, Aalberg V (2012) Body dissatisfaction and body mass in girls and boys transitioning from early to mid-adolescence: additional role of self-esteem and eating habits. BMC Psychiatry 12:1–9. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-12-35

Van den Berg PA, Mond J, Eisenberg M, Ackard D, Neumark-Sztainer D (2010) The link between body dissatisfaction and self-esteem in adolescents: similarities across gender, age, weight status, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. J Adolesc Health 47(3):290–296. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.004

Brechan I, Lundin I (2015) Relationship between body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: mediating role of self-esteem and depression. Eat Behav 17:49–58. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.12.008

Kong F, Zhang Y, You Z, Fan C, Tian Y, Zhou Z (2013) Body dissatisfaction and retrained eating: mediating effects of self-esteem. Soc Behav Personal 41(7):1165–1170. doi:10.2224/sbp.2013.41.7.1165

Stice E, Bearman SK (2001) Body image and eating disturbances prospectively predict increases in depressive symptoms in adolescent girls: a growth curve analysis. Dev Psychol 37:597–607. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.37.5.597

Ferreiro F, Seoane G, Senra C (2014) Toward understanding the role of body dissatisfaction in the gender differences in depressive symptoms and disordered eating: a longitudinal study during adolescence. J Adolesc 37(1):73–84. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.10.013

Haynos AF, Watts AW, Loth KA, Pearson CM, Neumark-Stzainer D (2016) Factors predicting an escalation of restrictive eating during adolescence. J Adolesc Health 59(4):391–396. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.011

Rodgers RF, Paxton SJ, Chabrol H (2010) Depression as a moderator of sociocultural influences on eating disorder symptoms in adolescent females and males. J Youth Adolesc 39:393–402. doi:10.1007/s10964-009-9431-y

Dakanalis A, Favagrossa L, Clerici M, Prunas A, Colmegna F, Zanetti MA, Riva G (2015) Body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptomatology: a latent structural equation modeling analysis of moderating variables in 18-to-28-year-old males. J Psychol 149(1):85–112. doi:10.1080/00223980.2013.842141

Sharpe H, Damazer K, Treasure J, Schmidt U (2013) What are adolescents’ experiences of body dissatisfaction and dieting, and what do they recommend for prevention? A qualitative study. Eat Weight Disord 18(2):133–141. doi:10.1007/s40519-013-0023-1

Jackson T, Chen H (2014) Risk factors for disordered eating during early and middle adolescence: a two year longitudinal study of mainland Chinese boys and girls. J Abnorm Child Psychol 42(5):791–802. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9823-z

Harrison K (2000) Television viewing, fat stereotyping, body shape standards and eating disorder symptomatology in Grade School children. Commun Res 27:617–640. doi:10.1177/009365000027005003

Sung-Yeon P (2005) The influence of presumed media influence on women’s desire to be thin. Commun Res 32(5):594–614. doi:10.1177/0093650205279350

Rajagopalan J, Shejwal B (2014) Influence of sociocultural pressures on body image dissatisfaction. Psychol Stud 59(4):357–364. doi:10.1007/s12646-014-0245-y

Homan K (2010) Athletic-ideal and thing-ideal internalization as prospective predictors of body dissatisfaction, dieting, and compulsive exercise. Body Image 7:240–245. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.02.004

Zanetti T, Santonastaso P, Sgaravatti E, Degortes D, Favaro A (2013) Clinical and temperamental correlates of body image disturbance in eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev 21:32–37. doi:10.1002/erv.2190

Ruuska J, Kaltiala-Heino R, Rantanen P, Koivisto AM (2005) Are there differences in the attitudinal body image between adolescent anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa? Eat Weight Disord 10:98–106. doi:10.1007/BF03327531

Cash T, Deagle E (1997) The nature and extent of body image disturbance in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord 22:107–125. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199709)22:2<107:AID-EAT1>3.0.CO;2-J

Sepulveda AR, Botella J, Leon JA (2001) La alteración de la imagen corporal en los trastornos de la alimentación: un meta-análisis. Psicothema 13:7–16

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington

Rodríguez-Sacristán J, Cadorze D, Rodríguez J, Gómez-Añón ML, Benjumea P, Pérez J (1984) Sistemas objetivos de medida: experiencia con el Inventario Español de Depresiones Infantiles (CEDI). Modificado de Kovacs y Beck. Revista de Psiquiatría Infanto-Juvenil 3:65–74

Kovacs M (1992) Children’s depression inventory, CDI. Multi-Health Systems Inc, Toronto

Rosenberg M (1965) La autoimagen del adolescente y la sociedad. Paidós, Buenos Aires

Vázquez A, Jiménez R, Vázquez R (2004) Escala de Autoestima de Rosenberg. Fiabilidad y validez en población clínica española. Apuntes de Psicología 22:247–255

Garner DM, Garfinkel PE (1979) The eating attitudes test: an index of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med 9:273–279. doi:10.1017/S0033291700030762

Castro J, Toro J, Salamero M (1991) The eating attitudes test: validation of the Spanish version. Evaluación Psicológica 7:175–190

Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE (1982) The eating attitudes test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med 12:871–878. doi:10.1017/S0033291700049163

Merino H, Pombo MG, Godás A (2001) Evaluación de las actitudes alimentarias y la satisfacción corporal en una muestra de adolescentes. Psicothema 13:539–545

Cooper PJ, Taylor MJ, Cooper Z, Fairburn CG (1987) The development and validation of the Body Shape Questionnaire. Int J Eat Disord 6:485–494. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(198707)6:4<485:AID-EAT2260060405>3.0.CO;2-O

Raich RM, Mora M, Soler A, Ávila C, Clos I, Zapater L (1996) Adaptación de un instrumento de evaluación de la insatisfacción corporal. Clínica y Salud 7:51–66

Toro J, Salamero M, Martínez E (1994) Assessment of sociocultural influences on the aesthetic body shape model in anorexia nervosa. Acta Psychiat Scand 89:147–151. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb08084.x

Cooper PJ, Taylor MJ (1988) Body image disturbance in bulimia nervosa. Br J Psychiatry 153:32–36

Rawana JS, Morgan AS, Nguyen H, Craig SG (2010) The relation between eating- and weight-related disturbances and depression in adolescence: a review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 13(3):213–230. doi:10.1007/s10567-010-0072-1

Amaya A, Álvarez GL, Mancilla JM (2010) Insatisfacción corporal en interacción con autoestima, influencia de pares y dieta restrictiva: Una revisión. Revista Mexicana de Trastornos Alimentarios 1:76–89

Smith AJ (2010) Body image, eating disorders and self-esteem problems during adolescence. In: Guindon MH (ed) Self-esteem across the lifespan: issues and interventions. Taylor & Francis Group, New York, pp 125–141

Whale K, Gillison FB, Smith PC (2014) ‘Are you still on that stupid diet?’: women’s experiences of societal pressure and support regarding weight loss, and attitudes towards health policy intervention. J Health Psychol 19(12):1536–1546. doi:10.1177/1359105313495072

Giordano S (2015) Eating disorders and the media. Curr Opin Psychiatry 28(6):478–482. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000201

Grabe S, Ward L, Hyde J (2008) The role of the media in body image concerns among women: a meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychol Bull 134:460–476. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460

Stice E, Shaw HE (2002) Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: a synthesis of research findings. J Psychosom Res 53(5):985–993. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00488-9

Skemp-Arlt KM (2006) Body image dissatisfaction and eating disturbances among children and adolescents: prevalence, risk factors and prevention strategies. J Pshys Educ Recreat Dance 75:32–39. doi:10.1080/07303084.2006.10597813

Espina A (2003) Eating disorders and MMPI profiles in a Spanish sample. Eur J Psychiatry 17(4):201–211. doi:10.1037/t06908-000

Thomas JJ, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Striegel-Moore RH, Beckler AE (2011) A latent profile analysis of the typology of bulimic symptoms in an indigenous Pacific population: evidence of cross-cultural variation in phenomenology. Psychol Med 41(1):195–206. doi:10.1017/S003329170000255

Linville D, Cobb E, Lenee-Bluhm T, López-Zerón G, Gau JM, Stice E (2015) Effectiveness of an eating disorder preventative intervention in primary care medical settings. Behav Res Ther 75:32–39. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2015.10.004

Stice E, Marti N, Spoor S, Presnell K, Shaw H (2008) Dissonance and healthy weight eating disorder prevention programs: long-term effects from a randomized efficacy trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 76:329–340. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.329

Stice E, Rohde P, Gau J, Shaw H (2012) Effect of a dissonance-based prevention program on risk for eating disorder onset in the context of eating disorder risk factors. Prev Sci 13(2):129–139. doi:10.1007/s11121-011-0251-4

Stice E, Butryn M, Rohde P, Shaw H, Marti N (2013) An effectiveness trial of a new enhanced dissonance eating disorder prevention program among female college students. Behav Res Ther 51:862–871. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2013.10

Rohde P, Auslander BA, Shaw H, Raineri KM, Gau JM, Stice E (2014) Dissonance-based prevention of eating disorder risk factors in middle school girls: results from two pilot trials. Int J Eat Disord 47(5):483–494. doi:10.1002/eat.22253

Yager Z, O’Dea JA (2008) Preventions programs for body image and eating disorders on university campus: a review of large controlled interventions. Health Promot Int 23:173–189. doi:10.1093/heapro/dan004

Levine MP, Smolak L (2016) The role of protective factors in the prevention of negative body image and disordered eating. Eat Disord 24(1):39–46. doi:10.1080/10640266.2015.1113826

Ciao AC, Loth K, Neumark-Sztainer D (2014) Preventing eating disorder pathology: common and unique features of successful eating disorders programs. Curr Psychiatry Rep 16(7):453. doi:10.1007/s11920-014-0453-0

Góngora V (2010) Hacia una integración de los paradigmas positivos y de enfermedad en la prevención de los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria en adolescentes. Psicodebate 10:279–296

Parkinson KN, Drewett RF, Le Couter AS, Adamson AJ (2012) Earlier predictors of eating disorder symptoms in 9-year-old children. A longitudinal study. Appetite 59(1):161–167. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2012.03.022

Jendrzyca A, Warschburger P (2016) Weight stigma and eating behaviours in elementary school children: a prospective population-based study. Appetite 102:51–59. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.005

Hui M, Brown J (2013) Factors that influence body dissatisfaction: comparisons across culture and gender. J Hum Behav Soc Environ 23:312–329. doi:10.1080/10911359.2013.763710

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, formal consent is not required (retrospective study).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Laporta-Herrero, I., Jáuregui-Lobera, I., Barajas-Iglesias, B. et al. Body dissatisfaction in adolescents with eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord 23, 339–347 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0353-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0353-x