Abstract

Purpose

Numerous studies have found perfectionism to show positive relations with eating disorder symptoms, but so far no study has examined whether perfectionistic self-presentation can explain these relations or whether the relations are the same for different eating disorder symptom groups.

Methods

A sample of 393 female university students completed self-report measures of perfectionism (self-oriented perfectionism, socially prescribed perfectionism), perfectionistic self-presentation (perfectionistic self-promotion, nondisplay of imperfection, nondisclosure of imperfection), and three eating disorder symptom groups (dieting, bulimia, oral control). In addition, students reported their weight and height so that their body mass index (BMI) could be computed.

Results

Results of multiple regression analyses controlling for BMI indicated that socially prescribed perfectionism positively predicted all three symptom groups, whereas self-oriented perfectionism positively predicted dieting only. Moreover, perfectionistic self-presentation explained the positive relations that perfectionism showed with dieting and oral control, but not with bulimia. Further analyses indicated that all three aspects of perfectionistic self-presentation positively predicted dieting, whereas only nondisclosure of imperfection positively predicted bulimia and oral control. Overall, perfectionistic self-presentation explained 10.4–23.5 % of variance in eating disorder symptoms, whereas perfectionism explained 7.9–12.1 %.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that perfectionistic self-presentation explains why perfectionistic women show higher levels of eating disorder symptoms, particularly dieting. Thus, perfectionistic self-presentation appears to play a central role in the relations of perfectionism and disordered eating and may warrant closer attention in theory, research, and treatment of eating and weight disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the past 30 years, research has produced converging evidence that perfectionism is positively related to eating disorder symptoms [1, 2]. Perfectionism is a personality disposition characterized by a striving for perfection that is expressed in exceedingly high standards of performance accompanied by self-criticism and concerns over negative evaluations by others [3–5]. One of the most influential and widely researched models of perfectionism is Hewitt and Flett’s model [4]. With the recognition that perfectionism has personal and social aspects, the model differentiates two main forms of perfectionism: self-oriented perfectionism and socially prescribed perfectionism.Footnote 1 Self-oriented perfectionism reflects internally motivated beliefs that striving for perfection and being perfect are important. Self-oriented perfectionists have exceedingly high personal standards, strive for perfection, expect to be perfect, and are highly self-critical if they fail to meet these expectations. In contrast, socially prescribed perfectionism reflects externally motivated beliefs that striving for perfection and being perfect are important to others. Socially prescribed perfectionists believe that others expect them to be perfect, and that others will be highly critical of them if they fail to meet their expectations [4, 6].

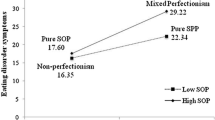

Numerous studies have investigated the relations of self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism and disordered eating (see [1, 2] for comprehensive reviews). Overall the findings suggest that both forms of perfectionism are positively related to eating disorder symptoms [1, 7–10], but may show different relations with different groups of eating disorder symptoms [11]. According to Garner and colleagues [12], it is important to differentiate three groups of eating disorder symptoms: (a) dieting reflecting behaviors such as engaging in diets, eating diet foods, and avoiding foods with sugar or high carbohydrate content, (b) bulimia and food preoccupation (consecutively referred to as bulimia) reflecting behaviors such as engaging in binge eating episodes without being able to stop or having the impulse to vomit after meals, and (c) oral control reflecting behaviors such as cutting food into small pieces or deliberately taking longer than others to eat meals. Both self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism have shown positive correlations with all three symptom groups, but socially prescribed perfectionism typically shows larger correlations than self-oriented perfectionism [10, 13] except with dieting where some studies found self-oriented perfectionism to show larger correlations than socially prescribed perfectionism [1, 9].

Furthermore, studies have started examining the relations of perfectionistic self-presentation and disordered eating. According to Hewitt and colleagues [14], perfectionistic self-presentation has two central concerns: to promote the impression that one is perfect, and to prevent the impression that one is not. To capture these concerns, Hewitt et al. developed a measure differentiating three aspects of perfectionistic self-presentation: perfectionistic self-promotion, nondisplay of imperfection, and nondisclosure of imperfection. Perfectionistic self-promotion is promotion-focused and driven by the need to appear perfect by impressing others, and to be viewed as perfect via displays of faultlessness and a flawless image. In contrast, nondisplay of imperfection and nondisclosure of imperfection are prevention-focused. Nondisplay of imperfection is driven by the need to avoid appearing as imperfect. It includes the avoidance of situations where one’s behavior is under scrutiny if this is likely to highlight a personal shortcoming, mistake, or flaw. In comparison, nondisclosure of imperfection is driven by a need to avoid verbally expressing or admitting to concerns, mistakes, and perceived imperfections for fear of being negatively evaluated [14, 15].

A number of studies have investigated whether perfectionistic self-presentation also plays a role in the relations that perfectionism shows with disordered eating, and the overall evidence suggests that it does. In a study comparing women diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, other women in psychiatric treatment (excluding eating disorders), and healthy controls, perfectionistic self-presentation was higher in the anorexia nervosa group than in the two control groups who did not differ in terms of perfectionistic self-presentation [16]. The same result was found in a study comparing female adolescents diagnosed with anorexia nervosa and a control group [17]. Furthermore, a study comparing female patients with an active eating disorder, partially recovered patients, fully recovered patients, and healthy controls found that patients with an active eating disorder and partially recovered patients showed higher levels of perfectionistic self-presentation than fully recovered patients and healthy controls [18]. Finally, two studies examining female university students found all three perfectionistic self-presentation aspects to show positive relations with eating disorder symptoms [11, 19], and the relations were particularly pronounced in women who were dissatisfied with their body and their physical appearance [19].

The studies’ findings are important because perfectionistic self-presentation is closely linked with perfectionism: people high in perfectionism also tend to be high in perfectionistic self-presentation [14]. Moreover, and more importantly perfectionistic self-presentation has been shown to explain why perfectionism is associated with psychological maladjustment: perfectionistic self-presentation shows positive relations with maladjustment, and these relations explain why perfectionism shows positive relations with maladjustment [14, 15]. Because perfectionism and perfectionistic self-presentation have both shown positive relations with disordered eating, Bardone-Cone et al. [1] proposed that perfectionistic self-presentation may also explain why perfectionism shows positive relations with disordered eating. So far, however, no study has investigated this proposition.

Against this background, the aim of our study was to provide a first investigation of whether perfectionistic self-presentation explains the relations that perfectionism shows with disordered eating by examining the relations of perfectionism (self-oriented, socially prescribed), perfectionistic self-presentation (perfectionistic self-promotion, nondisplay of imperfection, nondisclosure of imperfection), and eating disorder symptoms (dieting, bulimia, oral control) in a large sample of female university students. In line with the previous studies on perfectionism, perfectionistic self-presentation, and eating disorder symptoms in female university students [11, 19], we expected that perfectionism and perfectionistic self-presentation would show positive relations with the eating disorder symptoms. Furthermore, based on previous findings on perfectionism, perfectionistic self-presentation, and maladjustment [14, 15] and Bardone-Cone et al.’s proposition [1], we expected that perfectionistic self-presentation—when entered in multiple regression analyses together with perfectionism [20]—would explain the relations that perfectionism showed with the eating disorder symptoms.

Methods

Participants

A sample of 393 female students from the University of Kent was recruited via the School of Psychology’s Research Participation Scheme between 7 October and 12 December 2014. Mean age of students was 19.6 years (SD = 3.5). Students volunteered to participate for extra course credit or received a raffle ticket for a chance to win one Amazon® voucher of £50 (~US $73). The study was part of a larger study including additional measures (see [21], Study 2). Participants completed all measures online using the School’s Qualtrics® platform which required to respond to all items to prevent missing data. The average time participants took to complete the measures showed a median of 17.7 min.Footnote 2

Measures

To measure perfectionism, we used the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale [6] capturing self-oriented perfectionism (15 items; e.g., “I demand nothing less than perfection of myself”) and socially prescribed perfectionism (15 items; “People expect nothing less than perfection from me”). The items were presented with the scale’s standard instruction (“Listed below are a number of statements concerning personal characteristics and traits…”), and participants responded on a rating scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

To measure perfectionistic self-presentation, we used the Perfectionistic Self-Presentation Scale [14] capturing perfectionistic self-promotion (10 items; e.g., “I strive to look perfect to others”), nondisplay of imperfection (10 items; “I hate to make errors in public”), and nondisclosure of imperfection (7 items; “I should always keep my problems to myself”). Participants were asked to rate their agreement with the items on a rating scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree).

To measure Garner et al.’s eating disorder symptom groups, we used the Eating Attitudes Test-26 (EAT-26) [12] capturing dieting (13 items; e.g., “Engage in dieting behavior”), bulimia (6 items; “Have the impulse to vomit after meals”), and oral control (7 items; “Cut my food into small pieces”). Participants were asked to indicate how often they experienced the cognitions and behaviors described in the items responding on a rating scale from 0 (never) to 5 (always).

To control for individual differences in body size, participants were asked to indicate their weight and height which was then used to calculate their BMI. The BMI is the most widely used measure of body size accounting for height, and BMIs calculated from self-reported weight and height have shown high correlations (rs > 0.90) with BMIs from objective measurements [22, 23].

Data screening

Eight participants did not indicate their weight or height, so their BMI was estimated using the expectation–maximization algorithm in SPSS 21. We then computed scale scores for all measures by summing item responses. When inspecting the scores’ reliability (Cronbach’s alpha), all scores showed satisfactory alphas > 0.70. Because multivariate outliers can severely distort the results of correlation and regression analyses [24], we excluded four participants with a Mahalanobis distance larger than the critical value of χ2(9) = 27.88, p < 0.001 so the final sample comprised 389 women. Finally, we computed EAT-26 total scores following Garner et al.’s scoring procedure [12]. Results showed that 23.1 % of participants had a score of 20 or higher suggesting they were “at risk” of having or developing an eating disorder.

Results

First, we inspected the bivariate correlations between the variables (see Table 1). Both forms of perfectionism and the three perfectionistic self-presentation aspects showed positive intercorrelations. Moreover, all showed positive correlations with the eating disorder symptoms. Whereas neither perfectionism nor perfectionistic self-presentation showed significant correlations with BMI, all eating disorder symptoms did: dieting and bulimia showed positive correlations, and oral control showed a negative correlation. Women with a larger body size reported more dieting and bulimic symptoms, but less oral control than women with a smaller body size.

Next, we conducted a first series of multiple regression analyses [20] to examine whether perfectionistic self-presentation explained variance in eating disorder symptoms above perfectionism. Each analysis comprised three steps. In Step 1, we entered BMI as a control variable. In Step 2, we simultaneously entered the two forms of perfectionism as predictors. In Step 3, we simultaneously entered the three self-presentation aspects as predictors (see Table 2, Series 1). As regards dieting, self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism showed significant positive regression weights in Step 2 explaining 12.1 % of variance in dieting. Adding perfectionistic self-presentation in Step 3 explained a further 11.5 % of variance with all three self-presentation aspects showing significant positive regression weights. Moreover, with the addition of perfectionistic self-presentation, the regression weights of perfectionism became nonsignificant, suggesting that perfectionistic self-presentation explained the relations between perfectionism and dieting. As regards bulimia, only socially prescribed perfectionism was a significant positive predictor in Step 2 which explained 10.7 % of variance in bulimia. Adding perfectionistic self-presentation in Step 3 explained a further 5.1 % of variance, but individually none of the perfectionistic self-presentation aspects showed a significant regression weight. Moreover, socially prescribed perfectionism continued to be a significant positive predictor, suggesting that perfectionistic self-presentation did not explain the relations between perfectionism and bulimia. In addition, self-oriented perfectionism now showed a significant negative regression weight, suggesting that simultaneously entering perfectionism and perfectionistic self-presentation as predictors of bulimia created a suppression situation [25] in which self-oriented perfectionism predicted lower levels of bulimia symptoms. Also for oral control, socially prescribed perfectionism was the only significant positive predictor in Step 2 which explained 7.9 % of variance in oral control. Adding perfectionistic self-presentation in Step 3 explained only a further 3.2 % of variance, but—differently from bulimia—nondisclosure of imperfection emerged as a significant positive predictor of oral control. Moreover, socially prescribed perfectionism ceased to be a significant predictor, suggesting that nondisclosure of imperfection explained the relation between socially prescribed perfectionism and oral control.

To complement these analyses, we conducted a second series of multiple regression analyses (reversing the order in which perfectionism and perfectionistic self-presentation were entered) to examine whether perfectionism explained variance in eating disorder symptoms above perfectionistic self-presentation. Step 1 was the same as in the previous analyses, but the three perfectionistic self-presentation aspects were now entered as predictors in Step 2, and the two forms of perfectionism were entered in Step 3 (see Table 2, Series 2).Footnote 3 As regards dieting, all three perfectionistic self-presentation aspects showed positive regression weights in Step 2, but now explained 23.5 % of variance in dieting, whereas adding perfectionism in Step 3 did not explain any further variance (0.1 %). As regards bulimia, perfectionistic self-presentation explained 13.9 % of variance in Step 2, but individually only nondisclosure of imperfection was a significant positive predictor of bulimia in Step 2 and ceased to be significant predictor in Step 3 when perfectionism was added which explained a further 1.9 % of variance. As regards oral control, perfectionistic self-presentation explained 10.4 % of variance in Step 2, and again only nondisclosure of imperfection was a significant positive predictor individually. Differently from bulimia, however, adding perfectionism in Step 3 did not explain any further variance (0.1 %) and nondisclosure of imperfection remained a significant positive predictor after perfectionism was entered.

Discussion

The aim of our study was to provide a first investigation of whether perfectionistic self-presentation explains the relations that perfectionism shows with disordered eating. To this aim, we surveyed a large sample of female university students and employed multiple regression analyses to examine the relations that perfectionism (self-oriented, socially prescribed) and perfectionistic self-presentation (perfectionistic self-promotion, nondisplay of imperfection, nondisclosure of imperfection) showed with eating disorder symptoms (dieting, bulimia, oral control). As expected, perfectionism and perfectionistic self-presentation showed positive relations with the eating disorder symptoms. Both forms of perfectionism and all three aspects of perfectionistic self-presentation showed positive relations with dieting, whereas socially prescribed perfectionism and nondisclosure of imperfection showed positive relations with bulimia and oral control. Furthermore, the regression analyses indicated that perfectionistic self-presentation explained more variance in eating disorder symptoms than perfectionism. Moreover, perfectionistic self-presentation explained the relations that perfectionism showed with dieting and oral control.

The present findings provide support for Bardone-Cone et al.’s proposition [1] that perfectionistic self-presentation explains the relations of perfectionism and disordered eating. Moreover, the distinction between different groups of eating disorder symptoms—dieting, bulimia, and oral control according to Garner et al.’ suggestion [12]—allowed us to identify different patterns of relations with variables that are potential candidates to be risk or maintaining factors. As regards dieting, perfectionistic self-presentation explained 23.5 % of variance, and all three self-presentation aspects showed significant positive regression weights. In comparison, perfectionism explained only 12.1 % of variance, and the positive regression weights that self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism showed became nonsignificant when perfectionistic self-presentation was statistically controlled. Whereas the finding confirms previous findings that both forms of perfectionism play a role in dieting [1, 9, 10, 13], it also indicates that the relations of perfectionism and dieting are explained by perfectionistic self-presentation. The finding suggests that women high in perfectionism show more and stricter dieting than women low in perfectionism because they have a greater need to present themselves as perfect (and hide imperfections).

As regards oral control, perfectionistic self-presentation explained 10.4 % of variance, and nondisclosure of imperfection showed a significant positive regression weight. In comparison, perfectionism explained only 7.9 %, and the positive regression weight that socially prescribed perfectionism showed became nonsignificant when perfectionistic self-presentation was controlled for. The finding suggests that, for eating disorder symptoms associated with oral control, socially prescribed perfectionism plays a more important role than self-oriented perfectionism which is in line with findings that socially prescribed perfectionism has closer links with obsessive–compulsive behaviors than self-oriented perfectionism [4, 6]. Note, however, that also the relation of socially prescribed perfectionism and oral control was explained by perfectionistic self-presentation, particularly nondisclosure of imperfection. This is surprising because nondisclosure of imperfection reflects the need to avoid verbally expressing/admitting to concerns, mistakes, and perceived imperfections, whereas oral control includes behaviors that demonstrate self-control to others (e.g., “Take longer than others to eat meals,” “Display self-control around food”) [12]. Consequently, perfectionistic self-promotion or nondisplay of imperfection may have been expected to show stronger relations with oral control than nondisclosure of imperfection. Alternatively, the finding may indicate that women high in socially prescribed perfectionism use oral control to demonstrate they are in control of their eating to avoid disclosing problematic eating attitudes and behaviors. But this is speculative, and longitudinal data would be required to disentangle the temporal/causal relations between nondisclosure of imperfection and oral control (cf. “Limitations and future studies”).

As regards bulimia, perfectionistic self-presentation again explained more variance than perfectionism (13.9 vs. 10.7 %), but showed a different pattern of relations. Like with oral control, only socially prescribed perfectionism showed a significant positive regression weight. Different from oral control, perfectionistic self-presentation did not explain the positive relation between socially prescribed perfectionism and bulimia because socially prescribed perfectionism remained a significant positive predictor of bulimia when perfectionistic self-presentation was statistically controlled. In addition, self-oriented perfectionism became a negative predictor of bulimia. Because self-oriented perfectionism showed a positive correlation with bulimia when bivariate correlations were regarded, the negative effect of self-oriented perfectionism on bulimia (controlling for socially prescribed perfectionism and perfectionistic self-presentation) constitutes a suppression effect [25]. Whereas this effect has no practical relevance (e.g., no one would suggest to increase self-oriented perfectionism to decrease bulimia), it has theoretical relevance. Self-oriented perfectionism and socially prescribed perfectionism form part of two higher-order dimensions representing perfectionistic strivings and perfectionistic concerns [26, 27], and perfectionistic strivings often show negative relations with psychological maladjustment when perfectionistic concerns are statistically controlled, suggesting that perfectionistic strivings have adaptive aspects [27, 28]. In addition, self-oriented perfectionism has shown positive relations with self-control [29]. The latter would also explain why self-oriented perfectionism often shows weaker and less consistent associations with eating disorder symptoms other than dieting, when compared to socially prescribed perfectionism.

Limitations and future studies

The present study had a number of limitations. First, the study was the first to investigate whether perfectionistic self-presentation can explain the relations between perfectionism and disordered eating. Moreover, the percentages of variance in disordered eating that perfectionistic self-presentation explained beyond dispositional perfectionism were relatively small. Consequently, future studies need to replicate the findings before firm conclusions can be drawn [30]. Second, the study employed a cross-sectional design. Hence the results of the multiple regression analyses predicting eating disorder symptoms should not be interpreted in a causal or temporal fashion. Future studies may profit from employing longitudinal designs to examine whether perfectionism predicts longitudinal increases in eating disorder symptoms, and whether perfectionistic self-presentation can explain these longitudinal increases [31]. Third, the study examined female university students. Whereas this is the case with most studies investigating perfectionism and disordered eating [1], future studies would profit from reexamining the present findings in non-student samples, including clinical samples of women diagnosed with eating disorders to ensure that the findings generalize to community samples and clinical populations.

Conclusions

As the first study examining whether perfectionistic self-presentation can explain the positive relations between perfectionism and eating disorder symptoms, the present study makes an important contribution to the understanding of perfectionism and disordered eating. Our findings indicate that perfectionistic self-promotion, nondisplay of imperfection, and nondisclosure of imperfection play a central role in the relations that self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism show with dieting and oral control. Women who are driven by the need to appear perfect and to avoid the display and disclosure of imperfection show higher levels of dieting and oral control, and this need explains why women high in perfectionism show more and stricter dieting and oral control than women low in perfectionism. The present findings suggest that perfectionistic self-presentation plays a central role in the relations of perfectionism and disordered eating. Consequently, perfectionistic self-presentation deserves greater attention in theory and research on perfectionism and disordered eating as well as in the treatment of eating and weight disorders when patients show elevated levels of perfectionism.

Notes

The model differentiates a third form of perfectionism, other-oriented perfectionism, which is unrelated to eating disorder symptoms [1] and so was disregarded in the present study.

Because the platform gave participants unlimited time for completing the measures, the median is a better reflection of the average completion time than the mean.

In Step 3, the critical information is how the ΔR² values of Step 3 in Series 2 differ from those in Series 1. (The regression weights in Step 3 are the same in Series 1 and 2.)

References

Bardone-Cone AM, Wonderlich SA, Frost RO, Bulik CM, Mitchell JE, Uppala S, Simonich H (2007) Perfectionism and eating disorders: current status and future directions. Clin Psychol Rev 27:384–405. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.12

Wade TD, O’Shea A, Shafran R (2016) Perfectionism and eating disorders. In: Sirois FM, Molnar DS (eds) Perfectionism, health, and well-being. Springer, New York, pp 205–222. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-18582-8_9

Flett GL, Hewitt PL (2002) Perfectionism and maladjustment: an overview of theoretical, definitional, and treatment issues. In: Hewitt PL, Flett GL (eds) Perfectionism: theory, research, and treatment. American Psychological Association, Washington, pp 5–31. doi:10.1037/10458-001

Hewitt PL, Flett GL (1991) Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. J Pers Soc Psychol 60:456–470. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.456

Frost RO, Marten P, Lahart C, Rosenblate R (1990) The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Ther Res 14:449–468. doi:10.1007/BF01172967

Hewitt PL, Flett GL (2004) Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS): technical manual. Multi-Health Systems, Toronto

Bardone-Cone AM (2007) Self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism dimensions and their associations with disordered eating. Behav Res Ther 45:1977–1986. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2006.10.004

Chang EC, Ivezaj V, Downey CA, Kashima Y, Morady AR (2008) Complexities of measuring perfectionism: three popular perfectionism measures and their relations with eating disturbances and health behaviors in a female college student sample. Eat Behav 9:102–110. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.06.003

Lampard AM, Byrne SM, McLean N, Fursland A (2011) The Eating Disorder Inventory-2 perfectionism scale: factor structure and associations with dietary restraint and weight and shape concern in eating disorders. Eat Behav 13:49–53. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.09.007

Soares MJ, Macedo A, Bos SC, Marques M, Maia B, Pereira AT, Gomes A, Valente J, Pato M, Azevedo MH (2009) Perfectionism and eating attitudes in Portuguese students: a longitudinal study. Eur Eat Disord Rev 17:390–398. doi:10.1002/erv.926

Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Ediger E (1995) Perfectionism traits and perfectionistic self-presentation in eating disorder attitudes, characteristics, and symptoms. Int J Eat Disord 18:317–326. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199512)18:4<317:AID-EAT2260180404>3.0.CO;2-2

Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE (1982) The Eating Attitudes Test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med 12:871–878. doi:10.1017/S0033291700049163

Welch E, Miller JL, Ghaderi A, Vaillancourt T (2009) Does perfectionism mediate or moderate the relation between body dissatisfaction and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors? Eat Behav 10:168–175. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.05.002

Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Sherry SB, Habke M, Parkin M, Lam RW, McMurtry B, Ediger E, Fairlie P, Stein MB (2003) The interpersonal expression of perfection: perfectionistic self-presentation and psychological distress. J Pers Soc Psychol 84:1303–1325. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1303

Hewitt PL, Habke AM, Lee-Baggley DL, Sherry SB, Flett GL (2008) The impact of perfectionistic self-presentation on the cognitive, affective, and physiological experience of a clinical interview. Psychiatry 71:93–122. doi:10.1521/psyc.2008.71.2.93

Cockell SJ, Hewitt PL, Seal B, Sherry S, Goldner EM, Flett GL, Remick RA (2002) Trait and self-presentational dimensions of perfectionism among women with anorexia nervosa. Cognitive Ther Res 26:745–758. doi:10.1023/A:1021237416366

Castro J, Gila A, Gual P, Lahortiga F, Saura B, Toro J (2004) Perfectionism dimensions in children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Adolesc Health 35:392–398. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.11.094

Bardone-Cone AM, Sturm K, Lawson MA, Robinson DP, Smith R (2010) Perfectionism across stages of recovery from eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 43:139–148. doi:10.1002/eat.20674

McGee BJ, Hewitt PL, Sherry SB, Parkin M, Flett GL (2005) Perfectionistic self-presentation, body image, and eating disorder symptoms. Body Image 2:29–40. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.01.002

Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS (2003) Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences, 3rd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah

Stoeber J, Yang H (2015) Physical appearance perfectionism explains variance in eating disorder symptoms above general perfectionism. Pers Indiv Differ 86:303–307. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.06.032

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR (2010) Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. J Amer Med Assoc 303:235–241. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.2014

Lombardo C, Cuzzolaro M, Vetrone G, Mallia L, Violani C (2011) Concurrent validity of the Disordered Eating Questionnaire (DEQ) with the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) clinical interview in clinical and non clinical samples. Eat Weight Disord 16:188–198. doi:10.1007/BF03325131

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2007) Using multivariate statistics, 5th edn. Pearson, Boston

Tzelgov J, Henik A (1991) Suppression situations in psychological research: definitions, implications, and applications. Psychol Bull 109:524–536. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.109.3.524

Frost RO, Heimberg RG, Holt CS, Mattia JI, Neubauer AL (1993) A comparison of two measures of perfectionism. Pers Indiv Differ 14:119–126. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(93)90181-2

Stoeber J, Otto K (2006) Positive conceptions of perfectionism: approaches, evidence, challenges. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 10:295–319. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1004_2

Hill RW, Huelsman TJ, Araujo G (2010) Perfectionistic concerns suppress associations between perfectionistic strivings and positive life outcomes. Pers Indiv Differ 48:584–589. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.12.011

Trumpeter N, Watson PJ, O’Leary BJ (2006) Factors within multidimensional perfectionism scales: complexity of relationships with self-esteem, narcissism, self-control, and self-criticism. Pers Indiv Differ 41:849–860. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.03.014

Pashler H, Wagenmakers E-J (2012) Editors’ introduction to the special section on replicability in psychological science: a crisis of confidence? Perspect Psychol Sci 7:528–530. doi:10.1177/1745691612465253

Cole DA, Maxwell SE (2003) Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. J Abnorm Psychol 112:558–577. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558

British Psychological Society (2009) Code of ethics and conduct. British Psychological Society, London

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The study received no external funding. It was approved by the relevant ethics committee and followed the British Psychological Society’s code of ethics and conduct [32].

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stoeber, J., Madigan, D.J., Damian, L.E. et al. Perfectionism and eating disorder symptoms in female university students: the central role of perfectionistic self-presentation. Eat Weight Disord 22, 641–648 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0297-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0297-1