Abstract

Shame feelings often lead individuals to adopt compensatory mechanisms, such as the minimization of the public display or disclosure of mistakes and the active promotion of perfect qualities, conceptualized as perfectionistic self-presentation. Although perfectionism is considered a central characteristic of disordered eating, the investigation on the specific domain of body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation and on its relationship with psychopathology is still scarce. The main aim of the present study was exploring the moderator effect of body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation on the associations of shame with depressive symptomatology, and with eating psychopathology, in a sample of 487 women. Results revealed that body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation showed a significant moderator effect on the relationships of external shame with depressive symptomatology, and with eating psychopathology severity, exacerbating shame’s impact on these psychopathological indices. These findings appear to offer important clinical and investigational implications, highlighting the maladaptive character of such body image-focused strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In light of the biopsychosocial model, shame is a self-conscious emotion which emerges in the social context, from the experience of being perceived by others as flawed, inferior, inadequate, or powerless [e.g., 1–3]. These negative evaluations about the way others see the self are conceptualized as external shame, and involve the unsafe feeling of being ignored, criticized or rejected by others [e.g., 4, 5]. Shame may also be internalized, to the extent that individuals view and feel their own attributes or behavior as inferior and unattractive [6].

According to Gilbert [7], shame is a socially focused emotion of great evolutionary significance, which serves a defensive function to interpersonal threat. In this line, shame is elicited as a warning signal of unattractiveness, powerlessness and undesirableness [8–10], motivating defensive responses (e.g., to hide, escape, conceal or submit) in order to maintain the individual’s social rank and avoid rejection and possible damages to self-representation [e.g., 7, 9].

Notwithstanding the consideration of shame as an adaptive emotion, high levels of shame are associated with severe social difficulties, and have been consistently linked to the development and maintenance of different mental health conditions [11, 12], specifically depression [e.g., 4, 13, 14] and eating psychopathology [15–18].

Regarding eating psychopathology, shame has been regarded as a central feature [17, 20, 21]. In fact, several studies have shown that eating disorders’ patients, when compared to nonclinical groups, report higher levels of shame even after treatment [17, 20, 22, 23]. Additionally, literature suggests that pathological dieting and drive for thinness can function as a threat regulation strategy used to face shame [16, 24]. Moreover, Ferreira et al. [17] suggest that the control over weight or body shape may emerge as strategy to compete for social acceptance on women who present higher levels of external shame, and feel under pressure to attend to the social group’s demands.

Furthermore, there is consistent evidence on the role of shame on depression vulnerability [e.g., 17–25]. Actually, several studies have reported the association between depressive symptoms and both internal [e.g., 26] and external shame [e.g., 4, 13]. These data are in line with the evolutionary model, which conceives depression as a defensive response to loss events and perceptions of low rank, inferiority and powerlessness [e.g., 27, 28].

According to the evolutionary perspective, belonging to a group is essential to human survival and development [27]. Therefore, social acceptance is a primary need which implies being capable of promoting other’s interest and approval [29]. When dealing with feelings of inferiority, and to be accepted by others, individuals may adopt compensatory mechanisms to minimize or avoid the public display of mistakes and to actively promote perfect qualities. This mechanism, conceptualized as perfectionistic self-presentation [30], has been associated with various forms of psychological distress [29] and different clinical conditions, namely depression [e.g., 31, 32] and eating disorders [33–36].

Body shape has always been an important domain in self and social evaluations for women [37] and a particularly used dimension to attain acceptance and positive attention inside the social group [29]. Several studies have documented that, in the current Western cultures, the ideal standard of beauty and feminine attractiveness is based on a progressively leaner figure [e.g., 38], which appears to be associated with positive qualities of personality, power, and happiness [e.g. 39]. However, this current beauty standard is hardly attainable [38, 40], increasing body dissatisfaction in the majority of Western women [e.g., 41]. Since physical appearance constitutes a crucial evaluative dimension to women [16], this perception of discrepancy between one’s actual and the socially idealized body shape can generate considerably high levels of body dissatisfaction [e.g., 42, 43], which tends to promote feelings of inferiority and inadequacy, and subsequently increased levels of shame. Other than the psychological impact of shame, Lamont [12] highlighted that body shame predicted poor health outcomes, by promoting negative attitudes toward the body.

Physical appearance may be the women’s preferred domain to invest in when dealing with body dissatisfaction and when pursuing the purpose of being accepted and valued by others [24]. However, such investment may entail extreme control over eating habits, to reach perfection concerning body shape and weight [24; Ferreira, Duarte, Pinto-Gouveia, and Lopes, 2015]. This need to present a perfect physical appearance—body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation—seems particularly relevant due to its paradoxical effects, namely the increase of body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness [24]. Specifically, a recent study [24] revealed that the relationship between shame and weight control behaviors is mediated by increased levels of body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation. In fact, this study showed that 86 and 69 % of the effects of shame, external and internal respectively, were explained by their indirect effects on drive for thinness, through the perception of needing to present a perfect body image.

Along with clarifying the relationships between external shame, body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation, and the severity of depressive symptoms and eating psychopathology, the main purpose of this study was to test a model in which it is predicted that perfectionistic self-presentation focused on body image moderates the association of external shame, either with the severity of depressive symptomatology and with eating psychopathology. Considering theoretical and empirical knowledge on shame and its association with psychopathology, and on the pervasive role of perfectionistic self-presentation in women, it was expected that the adoption of body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation would play a moderator role, exacerbating the relationship between shame and psychopathology. However, this effect has never been empirically tested.

Methods

Participants

The present study is part of a wider research project about the eating behavior and emotion regulation processes in the Portuguese population, in which 863 individuals, comprising both college students and participants from the general population, participated. The ethical requirements were respected: the Ethic Committees and boards of the institutions involved approved the research, and all participants were fully informed about the nature and objectives of the study, the voluntary nature of their participation and the confidentiality of the data, which was exclusively used for research purposes. Individuals who agreed to participate in the research gave their written informed consent before completing the self-report questionnaires, with an approximate time duration of 15 min. The student sample was obtained in the classroom context, after authorization by the professor in charge, and in the presence of one of the researchers. Regarding the general population, a convenience sample was collected within the staff of distinct institutions (e.g., private companies, retail services), and questionnaires were completed during a break authorized by the respective institution’s boards.

In accordance with the aims of this study, data were cleaned in order to exclude (1) male participants and (2) participants who were older than 40 years, in order to comply with age and sex characteristics of the risk population’s features for body image and eating difficulties, and also (3) the cases in which more than 15 % of the responses were missing from a questionnaire. This process resulted in the final sample of 487 female participants.

Measures

Other as Shamer Scale (OAS) [5; Matos, Pinto-Gouveia, and Duarte, 2011]

This self-report measure evaluates external shame, i.e., the way how one believes others see the self. The scale consists of 18 items rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (“never”) to 4 (“almost always”), such as “Other people see me as not measuring up to them”, according to the frequency of the participant’s perceptions about the negative way others judge the self. The scale’s scores range from 0 to 72 points, with higher scores indicating greater external shame. The OAS showed excellent internal consistency, in both the original (α = .92; [5]), and the Portuguese versions (α = .91; Matos, Pinto-Gouveia, and Duarte, 2011).

Perfectionistic Self-Presentation Scale: Body Image (PSPS-BI) [Ferreira et al., 2015]

This scale evaluates the need to present a perfect body image to others, by displaying a flawless physical appearance and occulting perceived body imperfections. It consists of 19 items (such as “It is very important for me to present myself (my physical appearance) perfectly in social situations” or “I strive so that others do not become aware of certain characteristics of my body”) presented in a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“Completely disagree”) to 7 (“Completely agree”). As the scale ranges from 19 to 133, higher scores indicate a larger use of perfectionistic self-presentation attitudes in relation to the body image. The PSPS-BI showed good psychometric characteristics in the original study [Ferreira et al., 2015], with a high level of internal consistency (α = .88).

Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) [44, 45]

The EDE-Q is a self-report measure developed in the interest of overcoming the limitations of the Eating Disorder Examination interview. The EDE-Q has 36 items, comprising four subscales: restraint, eating concern, shape concern, and weight concern. The items are rated for the frequency of occurrence or for the severity of eating psychopathology, within a 28-day time frame. The scale ranges from 0 to 6 points, with higher scores indicating greater severity of eating psychopathology. In this study, we only used the global EDE-Q score, obtained by calculating the mean of the four subscale scores. EDE-Q demonstrated good psychometric properties (α = .94, for both the original [44] and the Portuguese versions [45]).

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21) [46, 47]

The DASS-21, a short version of DASS-42, is a self-report measure that accesses three negative emotional symptoms: (1) depression (DEP), (2) anxiety, and (3) stress, composed of 21 items. The items are rated on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (“Did not apply to me at all”) to 3 (“Applied to me very much, or most of the time”). The original scale [44] has shown good internal consistency (α = .94, .87, .91, for the depression, anxiety and stress subscales, respectively), as well as the Portuguese version (α = .84, .80, and .87, respectively; [47]). In this study’s analysis we only used the depression subscale, which ranges from 0 to 7 points, with higher scores indicating higher depressive symptomatology.

Cronbach’s alphas of these measures for the current study are reported in Table 1.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS (v.22; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Product-moment Pearson correlations analyses were conducted to explore associations between: external shame, body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation, depressive symptomatology, and the severity of eating psychopathology [48].

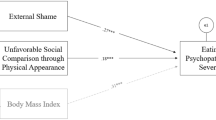

To test the moderator effect of body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation (PSPS-BI) in the relationship between external shame (OAS) and eating psychopathology’s severity (EDE-Q), and also in the relationship between OAS and depressive symptoms (DEP), a path analysis was performed to estimate the supposed relations of the suggested theoretical model (Fig. 1), using the software AMOS (Analysis of Momentary Structure, v.22, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The moderator model shows three causal paths to the dependent variables (DEP and EDE-Q): external shame; perfectionistic self-presentation focused on body image; and the interaction of these two variables. The moderation effect is corroborated if the interaction is significant. The Maximum Likelihood method was used to estimate all model path coefficients, and effects with p < .050 were considered statistically significant. To reduce the error related to multicollinearity, all continuous variables were standardized, and the values of both the predictor and the moderator (OAS and PSPS-BI) were centered, and then the interaction variable was obtained through the product of these variables [49].

The moderator role of PSPS-BI on the associations between OAS and DEP, and between OAS and EDE-Q. OAS Other as Shamer Scale, PSPS-BI Perfectionistic Self Presentation Scale – Body Image, OAS × PSPS-BI interaction between OAS and PSPS-BI, DEP Depression subscale of DASS-21, EDE-Q Eating Disorder Examination–Questionnaire (Global Score). **p < .01, ***p < .001

Lastly, two graphs were plotted to better understand the relationships between the predictor (OAS) and outcome variables (DEP and EDE-Q), with different levels—low, medium, and high—of the moderator (PSPS-BI). In these graphical representations, and since there were no theoretical cut points for PSPS-BI, the three curves were plotted taking into account the following cut-point values of the moderator variable on the x axis: one standard deviation below the mean, the mean, and one standard deviation above the mean, as recommended by Cohen and colleagues [48].

Results

Participants in this study were 487 females, 318 (65.3 %) college students and 169 (34.6 %) from the general population. The sample’s mean age was 24.38 (SD 6.14) years, with ages ranging from 18 to 40 years; and the mean of education’ years was 14.20 (SD 2.56). This sample presented a Body Mass Index (BMI) mean of 22.25 (SD 3.37), 77.41 % of the participants reported normal BMI values, 6.16 % were underweight, 13.56 % were overweight, and 2.87 % were obese [50], which reflects the BMI distribution of the female Portuguese population [51].

Descriptives

Means and standard deviations are presented in Table 1.

Correlations

Results showed that external shame (OAS) was positively and moderately correlated with body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation (PSPS-BI) and with the global score of the EDE-Q, and strongly linked to depressive symptomatology (DEP). Also, PSPS-BI was significantly and moderately correlated with DEP, and strongly associated with EDE-Q. Furthermore, significant and positive associations with moderate magnitudes were found between these two indicators of psychopathology, DEP and EDE-Q.

Partial correlation analyses of all variables in study were also conducted, controlling for age and BMI. Results showed that the direction and strength of the study variables’ correlations remained the same. For this reason, age and BMI weren’t included in the subsequent analyses.

Moderation analysis

The purpose of the path analysis was to test whether body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation (PSPS-BI) moderated the impact of external shame (OAS) on depressive symptomatology (DEP) and on eating psychopathology severity (EDE-Q). The tested theoretical model was fully saturated (with zero degrees of freedom), and consisted of 21 parameters.

All path coefficients in the model were statistically significant and explained 36 % of the depressive symptomatology’s variance and 51 % of eating psychopathology’s variance (Fig. 1).

First, the relationship between OAS, PSPS-BI and DEP was analyzed. Both OAS (b OAS = .200; SEb = .016; Z = 12.523; p < .001; β = .517) and PSPS-BI (b PSPS-BI = .019; SEb = .007; Z = 2.597; p < .010; β = .106) presented direct positive effects toward DEP. Furthermore, the interaction effect between the two variables was positive (b OASxPSPS-BI = .001; SEb = .001; Z = 2.621; p < .010; β = .097). All of the analysed effects were highly significant and results seem to indicate the presence of a moderator effect of PSPS-BI on the association between OAS and depressive symptomatology.

Concerning the association between OAS, PSPS-BI and EDE-Q, OAS presented a direct positive effect on EDE-Q (b OAS = .014; SEb = .004; Z = 3.663; p < .001; β = .132) and so did PSPS-BI (b PSPS-BI = .029; SEb = .002; Z = 16.883; p < .001; β = .600). Results showed that the interaction effect between the two variables was significant (b OASxPSPS-BI = .001; SEb = .000; Z = 5.011; p < .001; β = .163). All of the analysed effects were highly significant and suggested the existence of a moderator effect of PSPS-BI on the relationship between OAS and the severity of eating psychopathology symptomatology. Since this model was saturated, with all pathways statistically significant, the model fit indices were not examined.

Finally, to better understand the relationships between OAS and DEP, and between OAS and EDE-Q, in the presence of different levels of PSPS-BI (low, medium and high), two graphic representations were plotted (Figs. 2, 3 respectively).

Regarding depressive symptomatology (Fig. 2), the graphic representation allowed to observe that of the individuals who presented medium to high levels of OAS, those who showed higher tendency to adopt perfectionistic self-presentation strategies respecting their body image (PSPS-BI) tended to reveal higher levels of depressive symptomatology, in comparison to those with lower scores of PSPS-BI. Therefore, results seem to demonstrate that when individuals experience medium to high levels of shame, PSPS-BI exacerbates the impact of OAS on DEP. Also, this moderator effect is more evident when the experience of OAS is more intense.

With respect to eating psychopathology, the graphic representation (Fig. 3) revealed that for any level of shame, the individuals who presented higher levels of PSPS-BI tended to present higher levels of EDE-Q, comparing to those who presented lower tendency to adopt a body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation. Also, it is interesting to note that individuals who displayed higher levels of shame, but with lower tendency to endorse a body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation, revealed a tendency to present lower levels of EDE-Q, comparing to those with lower OAS scores but moderate to high levels of PSPS-BI. Thus, PSPS-BI seems to exacerbate the impact of OAS on EDE-Q, for any level of OAS experienced by the individuals.

Discussion

The present study underlines the pervasive effect of both shame and body image-related perfectionistic strategies on psychopathology, as it tested the exacerbation effect of these perfectionistic strategies on the association of shame with depressive and eating psychopathology severity.

Results were consistent with previous research, suggesting that external shame is linked to depressive symptomatology [4, 13], eating disordered psychopathology [e.g., 20], and also to perfectionistic self-presentation focused on body image [21]. Moreover, our study corroborated a positive and strong association between body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation and eating psychopathology severity [24; Ferreira et al., 2015], and extended the literature revealing a positive and moderate correlation with depressive symptomatology. This finding is in line with previous studies on the effects of perfectionistic strategies on depression [31, 32] but also provides further information on the association between the specific domain of body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation and higher levels of depressive symptomatology.

The moderator effect of perfectionistic self-presentation related to physical appearance on the relationships between external shame and depressive symptomatology, and eating psychopathology severity, was tested through a path analysis, and results confirmed the hypothesis. The tested model accounted for 36 % of the depressive symptomatology’s variance and for 51 % of disordered eating symptomatology’s variance.

Results showed that both shame and body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation presented direct and positive effects on depressive symptomatology and on overall eating psychopathology. Data also suggested a significant moderator effect of body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation on shame’s positive association with depressive symptoms severity and with eating psychopathology. These results seem to suggest that on females who strive to present their body image in a perfectionistic fashion, the negative impact of external shame on depressive and eating psychopathology is exacerbated.

The graphic representations elucidated this moderator effect. Firstly, concerning depressive symptomatology, the graphic shows that only for women who reported medium to high levels of shame, the ones with a higher tendency to engage in body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation strategies, revealed an increased level of depressive symptomatology, comparing to those in whom this strategy is less evident. Secondly, regarding disordered eating symptomatology, the graphic representation reveals an evident moderator effect at any level of external shame. To this respect, it was interesting to note that women who displayed higher levels of shame, but with a lower tendency to endorse body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation, revealed lower eating psychopathology severity, comparing to those who presented lower external shame scores and moderate to high levels of perfectionistic self-presentation focused on body image.

Altogether, these results seem to suggest that physical appearance-related perfectionistic self-presentation may consist in a paradoxical strategy to deal with negative feelings of external shame (e.g., inadequacy, inferiority). In fact, the results of this study suggest that the adoption of strategies to achieve a perfect body through the concealment of body imperfections and the display of body perfection tends to enhance the pathogenic impact of shame experiences on psychopathology indices. A possible explanation to such pathogenic effect may be the hardly attainable character of the current Western idealized body image, which turns the pursuit for a perfect body image into a task of extreme self-focus and control over one’s eating behaviors, with subsequent negative consequences on one’s mental and physical health.

Nonetheless, some methodological limitations should be considered when taking these results into account. First of all, the cross-sectional design limits the causality that could be drawn from our findings, therefore future studies should be longitudinal in order to determine the directionality of the relations and to corroborate the moderation effect of body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation. Furthermore, as shame may be conceptualized as a state, which can vary across specific contexts and situations, the interaction between shame experiences and the need to present a perfect body image should also be investigated using experimental designs manipulating shame levels. Secondly, the use of self-report measures may compromise the validity of the data. Furthermore, since our sample only consists of women from the general population, future studies should be conducted using different samples (e.g., male and clinical samples). Finally, since eating psychopathology and depression have multi-determined and complex natures, other variables (e.g., dieting, humiliation experiences, negative life events) and emotional regulation processes (e.g., submissiveness, self-criticism, rumination) may be involved. Nevertheless, the model’s design was purposely limited in order to explore the specific role of body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation.

This is the first investigation examining the moderator effect of perfectionistic self-presentation focused on body image in the association between shame and psychopathological symptomatology. In fact, this study underlines the pervasive effects of striving for a perfect body look, highlighting how body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation feeds the pathogenic impact of shame. Our findings appear to offer important investigational implications, but also seem to be new avenue to the development of intervention programs of mental health promotion among community women.

References

Lewis HB (1971) Shame and guilt in neurosis. International Universities Press, New York

Tangney JP, Dearing RL (2002) Shame and Guilt. Guilford Press, New York

Tracy JL, Robins RW (2004) Putting the self into self-conscious emotions: a theoretical model. Psychol Inq 15:103–125. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli1502_02

Allan S, Gilbert P, Goss K (1994) An exploration of shame measures-II: psychopathology. Personal Individ Differ 17:719–722. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(94)90150-3

Goss K, Gilbert P, Allan S (1994) An exploration of shame measures-I: the other as shamer scale. Personal Individ Differ 17(5):713–717. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(94)90149-X

Cook DR (1996) Empirical studies of shame and guilt: the internalized shame scale. In: Nathanson DL (ed) Knowing feeling: affect, script and psychotherapy. Norton, New York, pp 132–165

Gilbert P (2002) Body shame: a biopsychosocial conceptualisation and overview, with treatment implications. In: Gilbert P, Miles J (eds) Body shame: conceptualisation, research and treatment. Routledge, London, pp 3–54

Gilbert P (2003) Evolution, social roles and the differences in Shame and Guilt. Soc Res 70(4):1205–1230

Lewis M (1992) Shame: the exposed self. The Free Press, New York

Tangney J, Wagner P, Gramzow R (1992) Proneness to shame, proneness to guilt and psychopathology. J Abnorm Psychol 101:469–478. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.101.3.469

Hennig-Fast K, Michl P, Müller J, Niedermeier N, Coates U, Müller N, Engel RR, Möller HJ, Reiser M, Meindl T (2015) Obsessive-compulsive disorder : a question of conscience? An fMRI study of behavioural and neurofunctional correlates of shame and guilt. J Psychiatr Res 68:354–362. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.05.001

Lamont JM (2015) Trait body shame predicts health outcomes in college women: a longitudinal investigation. J Behav Med. doi:10.1007/s10865-015-9659-9

Gilbert P, Allan S, Goss K (1996) Parental representations, shame, interpersonal problems, and vulnerability to psychopathology. Clin Psychol Psychother 3:23–34. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0879(199603)3:1<23:AID-CPP66>3.0.CO;2-O

Pinto-Gouveia J, Matos M (2011) Can shame memories become a key to identity? The centrality of shame memories predicts psychopathology. Appl Cogn Psychol 25:281–290. doi:10.1002/acp.1689

Burney J, Irwin HJ (2000) Shame and guilt in women with eating disorder symptomatology. J Clin Psychol 56:51–61. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(200001)56:1<51:AID-JCLP5>3.0.CO;2-W

Goss K, Gilbert P (2002) Eating disorders, shame and pride: a cognitive-behavioural functional analysis. In: Gilbert P, Miles J (eds) Body shame: conceptualisation, research and treatment. Brunner-Routledge, New York, pp 219–255

Mustapic J, Marcinko D, Vargek P (2015) Eating behaviours in adolescent girls: the role of body shame and body dissatisfaction. Eat Weight Disord 20(3):329–335. doi:10.1007/s4051901501832

Pinto-Gouveia J, Ferreira C, Duarte C (2014) Thinness in the pursuit of social safeness: an integrative model of social rank mentality to explain eating psychopathology. Clin Psychol Psychother 21:154–165. doi:10.1002/cpp.1820

Troop NA, Redshaw C (2012) General shame and Bodily Shame in eating disorders: a 2.5-year longitudinal study. Eur Eat Disord Rev 20:373–378. doi:10.1002/erv.2160

Gee A, Troop NA (2003) Shame, depressive symptoms and eating, weight and shape concerns in a non-clinical sample. Eat Weight Disord 8(1):72–75. doi:10.1007/BF03324992

Murray C, Waller G, Legg C (2000) Family dysfunction and bulimic psychopathology: the mediating role of shame. Int J Eat Disord 1:84–89

Cooper MJ, Todd G, Wells A (1998) Content, origins and consequences of dysfunctional beliefs in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. J Cogn Psychother 12:213–230

Grabhorn R, Stenner H, Stangier U, Kaufhold J (2006) Social anxiety in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: the mediating role of shame. Clin Psychol Psychother 13:12–19. doi:10.1002/cpp.463

Ferreira C, Trindade IA, Ornelas L (2015) Exploring drive for thinness as a perfectionistic strategy to escape from shame experiences. Span J Psychol 18:E29. doi:10.1017/sjp.2015.27

Cheung MSP, Gilbert P, Irons C (2004) An exploration of shame, social rank and rumination in relation to depression. Personal Individ Differ 36:1143–1153. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00206-X

Tangney JP, Burggraf SA, Wagner PE (1995) Shame-proneness, guilt-proneness, and psychological symptoms. In Self-Conscious Emotions. In: Tangney JP, Fischer KW (eds) The Psychology of Shame, Guilt, embarrassment and pride. NewYork, Guilford, pp 343–367

Gilbert P (2000) The relationship of shame, social anxiety and depression: the role of the evaluation of social rank. Clin Psychol Psychother 7(3):174–189. doi:10.1002/1099-0879(200007)7:3<174:AID-CPP236>3.0.CO;2-U

Allan S, Gilbert P (1995) A Social Comparison Scale: psychometric properties and relationship to psychopathology. Personal Individ Differ 19:293–299. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(95)00086-L

Gilbert P, Price J, Allan S (1995) Social comparison, social attractiveness and evolution: how might they be related? N Ideas Psychol 13:149–165. doi:10.1016/0732-118X(95)00002-X

Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Sherry SB, Habke M, Parkin M, Lam RW, McMurtry B, Ediger E, Fairlie P, Stein MB (2003) The interpersonal expression of perfection: perfectionistic self-presentation and psychological distress. J Pers Soc Psychol 84(6):1303–1325. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1303

Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Ediger E (1996) Perfectionism and depression: longitudinal assessment of a specific vulnerability hypothesis. J Abnorm Psychol 105(2):276–280. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.105.2.276

Mackinnon SP, Sherry SB (2012) Perfectionistic self-presentation mediates the relationship between perfectionistic concerns and subjective well-being: a three-wave longitudinal study. Personal Individ Differ 53:22–28. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.02.010

Cockell SJ, Hewitt PL, Seal B, Sherry S, Goldner EM, Flett GL, Remick RA (2002) Trait and self-presentational dimensions of perfectionism among women with anorexia nervosa. Cogn Ther Res 26(6):745–758. doi:10.1023/A:102123741636

Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Ediger E (1995) Perfectionism traits and perfectionistic self-presentation in eating disorder attitudes, characteristics, and symptoms. Int J Eat Disord 18(4):317–326. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199512)18:4<317:AID-EAT2260180404>3.0.CO;2-2

McGee B, Hewitt P, Sherry S, Parkin M, Flett G (2005) Perfectionistic self-presentation, body image, and eating disorder symptoms. Body Image 2:29–40. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.01.002

Steele AL, O’Shea A, Murdock A, Wade TD (2011) Perfectionism and its relation to overevaluation of weight and shape and depression in an eating disorder sample. Int J Eat Disord 44:459–464. doi:10.1002/eat.20817

Gatward N (2007) Anorexia nervosa: an evolutionary puzzle. Eur Eat Disord Rev 1:1–12. doi:10.1002/erv.718

Sypeck MF, Gray JJ, Etu SF, Ahrens AH, Mosimann JE, Wiseman CV (2006) Cultural representations of thinness in women, redux: playboy magazine´s depictions of beauty from 1979 to 1999. Body Image 3(3):229–235. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.07.001

Strahan EJ, Wilson AE, Cressman KE, Buote VM (2006) Comparing to perfection: how cultural norms for appearance affect social comparisons and self-image. Body Image 3:211–227. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.07.004

Tiggemann M, Lynch JE (2001) Body image across the life span in adult women: the role of self-objectification. Dev Psychol 37(2):243–253. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.37.2.243

Spettigue W, Henderson KA (2004) Eating disorders and the role of the media. Can Child Adolesc Psychiatr Rev 1:16–19

Anton SD, Perri MG, Riley JR (2000) Discrepancy between actual and ideal body images: impact on eating and exercise behaviors. Eat Behav 1(2):153–160. doi:10.1016/S1471-0153(00)00015-5

Stice E, Shaw HE (1994) Adverse effects of the media portrayed thin-ideal on women and linkages to bulimic symptomatology. J Soc Clin Psychol 13(3):288–308. doi:10.1521/jscp.1994.13.3.288

Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ (1994) Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord 4:363–370. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199412)16:4%3c363:AID-EAT2260160405%3e3.0.CO;2-#

Machado PP, Martins C, Vaz AR, Conceição E, Bastos AP, Gonçalves S (2014) Eating disorder examination questionnaire: psychometric properties and norms for the Portuguese population. Eur Eat Disor Rev 22(6):448–453. doi:10.1002/erv.2318

Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH (1995) The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther 3:335–343

Pais-Ribeiro JL, Honrado A, Leal I (2004) Contribuição para o estudo da adaptação Portuguesa das Escalas de Ansiedade, Depressão e Stress (EADS-21). Psychologica 36:235–246

Cohen J, Cohen P, West S, Aiken L (2003) Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioural sciences, 3rd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New Jersey

Aiken LS, West SG (1991) Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, London, Sage

WHO (1995) Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Reports of a WHO Expert Commitee. WHO Technical Report series 854. Geneva, World Health Organization

Poínhos R, Franchini B, Afonso C, Correia F, Teixeira VH, Moreira P, Durão C, Pinho O, Silva D, Lima Reis JP, Veríssimo T, de Almeida MDV (2009) Alimentação e estilos de vida da população portuguesa: metodologia e resultados preliminares. Alimentação Humana 15(3):43–61

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marta-Simões, J., Ferreira, C. Seeking a perfect body look: feeding the pathogenic impact of shame?. Eat Weight Disord 21, 477–485 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0240-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0240-x