Abstract

Purpose of Review

The goals of this study were to identify smartphone apps targeting youth tobacco use prevention and/or cessation discussed in the academic literature and/or available in the Apple App Store and to review and rate the credibility of the apps. We took a multiphase approach in a non-systematic review that involved conducting parallel literature and App Store searches, screening the returned literature and apps for inclusion, characterizing the studies and apps, and evaluating app quality using a standardized rating scale.

Recent Findings

The negative consequences of youth tobacco use initiation are profound and far-reaching. Half of the youth who use nicotine want to quit, but quit rates are low. The integration of smartphone apps shows promise in complementing and enhancing evidence-based youth tobacco prevention and treatment methods.

Summary

Consistent with prior reviews, we identified a disconnect between apps that are readily accessible and those that have an evidence base, and many popular apps received low quality scores. Findings suggest a need for better integration between evidence-based and popular, available apps targeting youth tobacco use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nicotine is particularly addictive to youth, as is evidenced by the 38 million youth aged 13 to 15 years globally who currently use tobacco products [1]. Nicotine addiction is considered a pediatric disorder as more than 80% of adults who smoke initiated use before age 18, and 99% initiated use before age 26 [2]. Those who do not use tobacco as adolescents are unlikely ever to use [3]; therefore, tobacco use prevention during adolescence is key. Youth tobacco use is associated with increased risk for tobacco dependence and tobacco-related health problems later in life [4], further emphasizing the importance of preventing and reducing youth tobacco use.

Tobacco use prevention and cessation efforts have successfully reduced the initiation and intensity of cigarette smoking among young people over the past few decades [5•]. Policies that have proven effective include mass media and other informational campaigns (e.g., delivered in schools, in the community), raising taxes on tobacco products, banning advertising that targets the youth, restricting youth access to tobacco products, and establishing smoke-free environments [2]. However, with the emergence of new and higher-content nicotine products, increased variety of marketed tobacco products and youth-focused marketing, youth initiation, and consumption of other tobacco products has increased in recent years [6].

E-cigarettes (“cig-a-likes”), vapes (a term that applies to both nicotine and cannabis [THC, CBD] delivery), pods (e.g., JUUL), and other electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) pose a risk to the decades of progress made in reducing and preventing youth tobacco/nicotine use. These products boast a variety of appealing flavors and innovative designs (e.g., new or novel products, positive sensory experiences) and are targeted in youth-focused marketing [7]. Recent data suggest that e-cigarettes are contributing to a youth nicotine addiction epidemic [8•]. In 2022, 16.5% of high school students and 4.5% of middle school students in the USA, or approximately 3 million total youth, reported past 30-day use of any tobacco product [8•]. E-cigarettes were the most used type of devices (9.4%), with cigarettes used by fewer youth (1.6%; [8•]). High prevalence rates of youth e-cigarette use have generated renewed emphasis on tobacco use prevention and cessation efforts.

Approximately half of youth who use tobacco have made a past-year quit attempt [9]. Given the lasting negative health effects and low rates of cessation, it is necessary to better reach and engage youth in tobacco-related prevention and cessation efforts. To this end, there is a need for innovative and appealing methods to deliver evidence-based prevention and cessation interventions early to young people, yet there are limited effective interventions and delivery strategies for use with youth, particularly for the treatment of tobacco use and dependence [10]. One way to improve reach and engagement in tobacco use prevention and intervention among youth is through digital health technology such as smartphone apps. This approach shows promise in complementing and enhancing evidence-based methods (e.g., counseling, pharmacotherapy) in several ways. First, evidence-based methods are typically delivered in person, whereas smartphone apps allow remote access to prevention information and treatment, facilitating scalability, equity, and reach [11, 12], although continued efforts to bridge the “digital divide” to ensure equity are needed [13]. Nevertheless, the delivery of remote tobacco use content via apps overcomes notable barriers to treatment access, such as cost, transportation, and time, which are especially prominent for youth [14]. Second, smartphones are readily available to youth, and 95% of US teens have smartphone access at home [15]. Accessing tobacco use content in youth’s own environment and in real time may boost efficacy [16]. Third, tobacco use content can be delivered with high fidelity (i.e., fidelity of treatment delivery can be standardized; [17]). Fourth, the relative anonymity of smartphone apps reduces the potential stigma that can be associated with disclosing the need for tobacco use–related support to parents and other family members, teachers, and friends. Finally, apps have multiple features such as treatment components, connection to peer support, and gamification, all of which may appeal to youth and have the potential to improve engagement.

To this end, there has been a proliferation of smartphone apps targeting tobacco use generally, yet several reviews of the availability, content, and quality of these apps indicate that most lack an adequate scientific evidence base. For example, among the top 50 smoking cessation apps available in app stores targeted to a general audience or adults, only two had any scientific support [18], and apps with low quality scores were among the most popular in the app store [19]. App content rarely adheres to the US Clinical Practice Guidelines for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence, and very few apps have been tested for effectiveness [19, 20]. The content available in tobacco apps targeted to youth shows more promise. A content analysis of youth-focused smoking cessation apps found that youth apps are more likely to incorporate clinical practice guidelines than general audience apps; however, effectiveness testing is still limited [21•]. Content was largely deemed developmentally appropriate, indicating that youth apps have the potential to deliver tobacco use information to youth more effectively than apps geared to general audiences.

This study aimed to identify and evaluate the evidence base for youth-focused tobacco apps. We updated the search by Robinson and colleagues (2018) and widened it in several ways. First, we reviewed both tobacco use prevention and cessation apps, as previous work largely focused on smoking cessation apps. Second, we included apps identified from the scientific literature in addition to those identified in the Apple App Store (hereafter App Store) based on select criteria. We took this approach to increase the likelihood of identifying relevant apps, as many evidence-based apps are in the early-phase research and may not yet be available in app stores, and apps in the App Store may not be identifiable in the literature if they have not been empirically evaluated. Third, we included apps that targeted any tobacco product (i.e., not just combustible cigarettes), including apps that targeted vaping specifically and apps that targeted substance use generally if tobacco use was included. Finally, we evaluated the quality of the identified apps using a common app rating scale to understand their evidence base.

Methods

Procedures

In Phase 1, we conducted a literature search on PubMed for peer-reviewed articles reporting on the development, refinement, or testing of youth tobacco use prevention and/or cessation apps. In Phase 2, we identified youth tobacco use prevention and/or cessation apps available in the App Store. Phases 1 and 2 took place in November 2022. In Phase 3, we cross-referenced apps identified in the literature (Phase 1) and in the App Store (Phase 2) to identify overlap. We subsequently searched the App Store for apps identified from the literature and searched PubMed for literature associated with apps identified from the App Store. In Phase 4, apps were characterized and scored for quality of evidence base.

Phase 1: PubMed Search

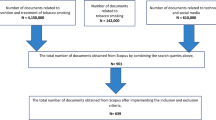

Articles were identified using the following search terms (Fig. 1), limiting the search to title and/or abstract: (adolescent OR youth) AND (tobacco OR vape OR vaping OR drug OR substance use) AND (prevention OR cessation OR quit) AND (smartphone OR mobile). Search terms were selected based on prior studies [21•] and broadened to address the study aims (e.g., to include prevention, vaping). Articles were deemed eligible for inclusion if they reported an empirical effort to develop, refine, or test a tobacco use prevention and/or cessation app, consistent with Vilardaga et al. (2019). All abstracts (N = 73) were reviewed by two authors; three abstracts required adjudication from a third author; n = 13 eligible articles were identified.

Phase 2: Apple App Store Search

Apps were identified through a multi-stage process (Fig. 1). First, the App Store was searched using 12 terms adapted from those used in the Phase 1 literature search, focused on teens; smoking, vaping, or other drugs; and quitting. Two authors independently searched the App Store. We report the total number of apps returned for each search term. We then selected the top 20 apps returned per search term, in line with earlier studies [21•]. We eliminated overlap in apps between search terms (n = 51). Finally, apps were determined to be eligible for inclusion and further review if relevant to youth tobacco use prevention and/or cessation based on the app name, age, and description at the level of the App Store (n = 10). We opted to search the App Store over Google Play because recent data indicated that youth overwhelmingly prefer iPhones to Androids (87% of youth surveyed currently own an iPhone [22]) and because smoking cessation apps for Android and iOS have been found to be largely similar [19, 23].

Phase 3: Overlap Between PubMed and App Store Search Results

Apps identified in the literature and App Store searches were cross-referenced to identify overlap. Apps identified in the literature search in Phase 1 that were unique from apps identified in the App Store in Phase 2 were searched by name in the App Store (identifying n = 2 additional apps). One of these apps was deemed ineligible (not geared toward youth) and was removed, resulting in 11 apps available for review in Phase 4. Likewise, apps identified in the App Store search in Phase 2 that were unique from those identified in the literature search in Phase 1 were searched in PubMed (identifying n = 1 additional paper).

Phase 4: Literature and App Review

Eligible articles (N = 14) identified through Phase 3 were reviewed, and the following information was extracted: citation, app name, location, type of substance/tobacco product targeted, prevention and/or cessation focus, stage according to the NIH Stage Model of Behavioral Intervention Development (i.e., Stage 0: basic science; Stage 1: creation of a new intervention, modification of an existing intervention, and/or feasibility/pilot testing; Stage 2: behavioral interventions in research settings; Stage 3: testing in a community context(s); Stage 4: effectiveness research; [17]), a brief description of the study design, targeted population, age range, and sample size.

All apps retained in Phase 3 (n = 11) were downloaded and reviewed independently by two authors, who agreed to a reasonable review period (10–15 minutes for each app) to obtain the information outlined below, as an individual user might do when evaluating whether or not to engage with an app. Reviewers completed the Mobile Apps Rating Scale (MARS [24]) App Classification and App Information (Section D) sections, which are described below. These sections were considered the most relevant to scientific review, with other MARS sections (engagement, functionality, aesthetics, and app subjective quality) being more related to usability and therefore considered more appropriate for a user to evaluate.

MARS App Classification

The App Classification section of the MARS is used to collect descriptive and technical information about the app with information obtained by reviewing the app description in the App Store. This classification included app name, version, date of last update, developer/affiliations (commercial, government, NGO, university), rating of the current version, rating of all versions, N ratings of the current version, N ratings of all versions, cost of the basic version, cost of an upgrade version, and download platform (iPhone and/or iPad). The authors also coded the apps as prevention and/or cessation-focused and the target substance(s). Targeted age group (children under 12, adolescents 13–17, young adults 18–25, adults, general) was noted. The App Classification section also includes select-all-that-apply for app focus (i.e., what the app targets), including increase happiness/well-being, mindfulness/meditation/ relaxation, reduce negative emotions, depression, anxiety/stress, anger, behavior change, alcohol/substance use, goal setting, entertainment, relationships, physical health, and others, and for app theoretical background/strategies, including assessment, feedback, information/education, monitoring/tracking, goal setting, advice/tips/strategies/skills training, CBT-behavioral (positive events), CBT-cognitive (thought challenging), ACT (acceptance commitment therapy), mindfulness/meditation, relaxation, gratitude, strengths-based, and others. Coding also took place for technical aspects of the app, including allows sharing (Facebook, Twitter, etc.), has an app community, allows password protection, requires login, sends reminders, and needs web access to function.

MARS App Information (Section D)

MARS App Information (Section D) captures the degree to which the app contains high-quality information (e.g., text, feedback, measures, references) from a credible source. This MARS section includes seven items, each rated on a Likert scale from 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest) (with an option for N/A on items 2–5 and 7), including (1) accuracy of app description (in app store): Does app contain what is described?; (2) goals: Does app have specific, measurable, and achievable goals (specified in app store description or within the app itself)?; (3) quality of information: Is app content correct, well written, and relevant to the goal/topic of the app?; (4) quantity of information: Is the extent of coverage within the scope of the app? and comprehensive but concise?; (5) visual information: Is visual explanation of concepts – through charts/graphs/images/videos, etc. – clear, logical, correct?; (6) credibility: Does the app come from a legitimate source? (specified in the app store description or within the app itself, i.e., a commercial business with a vested interest is scored 1, while an app developed using nationally competitive government or research funding is scored 5); and (7) evidence base: Has the app been trialed/tested; must be verified by evidence (in published scientific literature)? A mean score (from 1 to 7) was calculated, with higher scores indicating higher-quality information.

Results

Phase 1: PubMed Search

Of 73 papers returned to the search terms, the literature search yielded 13 manuscripts that met the screening criteria (Fig. 1; Table 1).

Phase 2: App Store Search

The App Store search resulted in the identification of 51 unique apps within the top 20 results after eliminating the overlap between 12 search terms. Of those, 10 apps were determined relevant to youth tobacco use prevention and/or cessation based on app names and descriptions at the level of the App Store and were therefore deemed eligible for inclusion and downloaded for further review (Table 2). One app, smokeSCREEN, required approval from the developers to download. The authors were not granted access at the time of submission of this manuscript, and therefore, this app was not reviewed. This process resulted in a total of nine apps identified from the App Store search. We note that, according to their App Store descriptions, all apps were available in English, DynamiCare Health was also available in Spanish and Portuguese, and Smokerface was available in 13 languages. English language apps were evaluated for this study.

Phase 3 Results: Overlap Between PubMed and App Store Searches

There was no overlap between apps identified in the literature and App Store searches; thus, apps identified in the literature (n = 13) were searched by name in the App Store, and apps identified in the App Store were searched by name in PubMed. Of 13 papers, four apps were found in the App Store: DynamiCare Health, Mind Your Mate, Smokerface, and ready4life. Mind Your Mate was only available to participants registered in the Mind Your Mate study, and therefore, this app was not included to be reviewed. Ready4life was determined to not be geared toward the youth based on the app description in the App Store and was not included to be reviewed. DynamiCare Health and Smokerface were included to be reviewed, in addition to the 9 apps identified in the App Store (Phase 1 [literature search] n = 2; Phase 2 [App Store] n = 9). Additionally, one app identified in the App Store, smokeSCREEN [25], had supporting literature available in PubMed (Table 1).

Phase 4 Results: Literature and App Review

Literature Review (Table 1)

Studies spanned all stages of the NIH Stage Model for Behavioral Intervention Development, including seven manuscripts reporting Stage I studies involving intervention generation, refinement, modification, adaptation, and pilot testing [26,27,28,29,30,31,32] and one Stage II study involving traditional efficacy testing [33]. The remaining five manuscripts were protocol papers for planned or ongoing trials including one Stage I [34], two Stage II trials [35, 36], one Stage III trial for efficacy testing with real-world providers [37], and one Stage IV trial for effectiveness research [38]. Regarding substances, four interventions targeted cigarette smoking [26, 27, 32, 34], one targeted nicotine vaping [30], and the remaining interventions targeted tobacco use within substance use generally [29, 33, 37, 38] or within substance use in HIV prevention [28, 31, 35, 36]. Within this, three interventions explicitly reported targeting cannabis use [29, 33, 37]. Six papers were related to substance use prevention [26, 29, 32, 33, 37, 38], two were related to cessation [30, 34], one was related to both prevention and cessation [27], and four were related to substance use within HIV prevention [28, 31, 35, 36]. Six studies were reported in the USA [28, 30, 31, 33, 35, 36], and the remaining seven studies were reported in Australia [38], Canada [27], Europe [26, 29, 37], and Mexico [32]. Although the language of the intervention was not well-reported across studies, it appeared that interventions were delivered in English [19, 20, 22, 23, 25,26,27,28, 30, 31] or another language [18, 21•, 24, 29]. Five interventions specifically targeted adolescents [26, 29, 32, 33, 38], two targeted young adults [31, 34], and six targeted both adolescents and young adults [27, 28, 30, 35,36,37]. Five interventions were school-based [26, 29, 32, 37, 38], two were targeted to the youth generally [28, 30], and the remaining six were targeted to specific populations such as the youth experiencing homelessness, LGBTQ youth and young adults, young men who have sex with men, and other groups [27, 31, 33,34,35,36].

App Classification

App information is described in Table 2. MD Anderson developed three of the ten apps (Tobacco Free Teens, Tobacco Free Family, Vaper Chase). The remaining apps were developed by a small NGO/institution (Caron’s Connect 5, BeatNic Boulevard), by the government, university, or a larger scale institution (DynamiCare Health), through nationally competitive government or research funding (Smokerface), by seemingly legitimate but unverifiable sources (Teen Hotlines, Pulmonary Scan) or by identifiable but questionably legitimate sources (Fuul, Escape the Vape). Of 11 apps reviewed, utilization of coded technical aspects was variable, including sharing (n = 4), app community (n = 2), password protection (n = 5), required login (n = 6), reminders (n = 4), and web access to function (n = 5). Focus (what the app targets) was “alcohol/substance use” for all apps (all apps addressed tobacco use, as per our inclusion criteria). Behavior change (n = 7), physical health (n = 5), entertainment (n = 5), goal setting (n = 4), and relationships (n = 4) were each targeted in approximately half of the apps reviewed. Happiness/well-being (n = 2), mindfulness/meditation/relaxation (n = 2), depression (n = 1), anxiety/stress (n = 2), and others (n = 1) were less frequently targeted, while reduction of negative emotions and anger were not focal to any app reviewed.

Five of the 11 apps were prevention-focused, three were cessation-focused, and three emphasized both prevention and cessation. Regarding targeted tobacco products, cigarette smoking was the exclusive focus of two apps (Tobacco Free Teens, Smokerface), vaping was targeted in three apps (Vaper Chase, Escape the Vape, Fuul), multiple tobacco products were targeted in five apps (Tobacco Free Family, Caron’s Connect 5, Pulmonary Scan, BeatNic Boulevard, DynamiCare Health), and the targeted substance was not identifiable in one app (Teen Hotlines).

MARS App Information Scores

Average MARS App Information (Section D) quality scores are reported in Table 2 and ranged from 2.8 (Fuul) to 5 (Tobacco Free Family).

Discussion

The goals of this study were to identify smartphone apps targeting youth tobacco use prevention and/or cessation in the scientific literature and App Store and to characterize and score the quality of the apps from a scientific credibility perspective. We took a multiphase approach that involved conducting parallel literature and App Store searches, screening the returned literature and apps for inclusion, characterizing the studies and apps, and evaluating app quality using a standardized rating scale.

We identified 14 manuscripts reporting the development and testing of youth tobacco apps. As described in Tables 1 and 2, most studies were geared toward tobacco use prevention/cessation among subgroups of the youth who have higher rates of tobacco use relative to the general population [39,40,41]. Regarding the stage of research of the studies identified, approximately two-thirds of the studies reviewed were in Stage I (i.e., creation of a new intervention, modification of an existing intervention, and/or feasibility/pilot testing), indicating that much of this work remains in early stages, as reported previously [20]. This may explain why only three apps identified in the literature search (DynamiCare Health, Smokerface, ready4life) were accessible.

Eleven apps met the criteria for review. Very few apps for smoking prevention and/or cessation were returned when search terms included the word “teen” relative to search terms that did not specify “teen.” For example, “teen quit smoking” yielded far fewer results (n = 5) than “quit smoking” (n > 100). However, the youth are not likely to search for apps that are specifically designed for them and are more likely to access general audience apps [18]. There is a need to deliver high-quality tobacco use prevention/cessation content to the youth. Addressing this need requires thoughtful consideration of search terms and how to connect youth to these apps, as well as efforts aimed to tailor these apps to contain content appealing to youth. Although youth may access apps directly, parents, schools, healthcare providers, and others may serve as intermediaries to connect the youth with apps best suited to them and may use the term “teen” in searches. Additional efforts to promote apps to these groups are needed. For example, one tobacco app identified in the App Store search, BeatNic Boulevard, was developed by a local school district in collaboration with the Stanford Tobacco Prevention Toolkit. Another app, Storytelling 4 Empowerment, targeted youth-centered community health clinics to engage youth in prevention services related to sexual risk behaviors and testing and substance use, including tobacco. Likewise, several apps tested and discussed in the literature were school-based.

Literature and App Store searches contained no overlap in apps, indicating a disconnect between apps that are readily accessible and those that have an evidence base. Although the literature review identified 13 studies of apps (one paper was later identified by searching for the apps in PubMed), only four were found upon searching by name in the App Store (DynamiCare Health, Mind Your Mate, Smokerface, ready4life). Likewise, only one app identified from the App Store search has been empirically tested (Smokerface). A main challenge is identifying App Store search terms that return evidence-based apps, which are more likely to be returned when search terms use more formal language, such as “smoking cessation” vs. “quit smoking,” whereas the youth who use tobacco products are more likely to use plain language. Even using the search term “stop” instead of “quit” might have returned different results and might be more in line with search terms used by the youth. Although we were able to find a few apps from the literature by searching by name in the App Store, this is not likely to be a typical real-world approach to finding apps. One solution suggested by others [18], and in line with our findings, is to connect researchers with app developers and App Store indexers to collaborate toward (a) a plain language approach, (b) categorization and organization of apps by scientific merit/underlying medical theory, and (c) providing users with tools that refine search results and sort order to highlight evidence-based apps.

Regarding the MARS App Classification, targeting multiple determinants of tobacco use can enhance the effectiveness of tobacco use youth prevention and cessation efforts [42]. Consistent with this, all apps reviewed included multiple intervention targets. Caron’s Connect 5 focused on 7 intervention targets, the most of all apps reviewed. Smokerface had the fewest intervention targets (two). Behavior change, physical health, entertainment, goal setting, and relationships were each targeted in approximately half of the apps reviewed. None of the apps reviewed targeted reductions in negative emotions, only two targeted anxiety/stress, and only one targeted depression, which is surprising given that the modulation of negative affect can motivate cigarette smoking [43]. Regarding intervention content, it is notable that none of the apps reviewed and only 4 of the papers included cannabis content. Dual use of nicotine and cannabis vaping is common among the youth; in fact, researchers have called for interventions targeting youth e-cigarette use to consider the dual use of these products [44]. Our findings align with this call; none of the apps mention cannabis use at the level of the app store description, and only four papers (three identified in Phase 1 and one identified in Phase 3) target cannabis.

MARS quality scores ranged from 2.4 for Fuul to 5 for Tobacco Free Family. Tobacco Free Family was developed by MD Anderson Cancer Center to target cigarette and e-cigarette use prevention in the general population (i.e., not specific to the youth), and in addition to substance use, the app focuses on entertainment and relationships. Technical aspects include that the app allows sharing and requires web access to function. The theoretical background relies on information and education. However, as noted above, Tobacco Free Family included a low number of intervention targets. Thus, although this app received the highest MARS quality score, the MARS does not reflect considerations such as including multiple intervention targets, which are meaningful to youth-specific tobacco prevention/cessation. Although these apps received high MARS quality scores, they were not identified as having an evidence base in the literature. Additionally, these apps had the lowest number of user reviews in the App Store (Tobacco Free Teens, N = 5; Tobacco Free Family, N = 1). Likewise, and in line with prior reviews [19], several apps that were rated highly in the App Store received low MARS quality scores. For example, Escape the Vape had a high user rating (4.8) and the highest number of user ratings (N = 315) of apps reviewed in the App Store, yet received a low MARS quality score (2.8), suggesting that this lower quality app may be more popular than higher-quality apps.

In line with previous reviews of tobacco use smartphone apps, we found that app developer was related to app credibility. For example, Robinson et al. (2018) found four smoking cessation apps by a university or government agency and speculated that the quality of app content may be variable based on the developer (e.g., public health organization, private company, individual, other entity). Another recent review of smoking cessation apps suggested that app developer type (i.e., affiliation with a healthcare professional) influences app quality [45]. In our study, we found that apps developed by credible sources (e.g., small NGO/institution) and/or supported by government funding received higher MARS quality scores, keeping in mind that “credibility” is calculated into the MARS quality score. In addition to the MD Anderson Cancer Center apps (Tobacco Free Family, Tobacco Free Teen), another app that scored highly was DynamiCare Health (also the developer’s name). DynamiCare Health focuses on behavior change, alcohol/substance use, goal setting, and relationships, among adults, using several theoretical approaches, including assessment, feedback, information/education, monitoring/tracking, goal setting, advice/tips/strategies/skills training, CBT, and strengths-based. Some features were not included in the MARS but were found in the app description at the level of the App Store, including that the app uses contingency management and pairs users with a personal health coach for video chat–based support. Interestingly, DynamiCare Health has two prescription-only digital therapeutics [46, 47] that have been granted Breakthrough Device Designation from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). No apps reviewed here, and very few mental health apps more broadly, have been granted FDA approval, because most do not meet the criteria for “software as a medical device” regulated by the FDA. This highlights the need for a regulatory framework for digital mental healthcare including addiction treatment [48].

Our findings build on a prior content analysis of smartphone apps for adolescent smoking cessation by Robinson et al. (2018). That review reported eight adolescent apps identified in Google Play and the App Store (searched in 2016), with only two in the App Store. Of those, Tobacco Free Teens was also identified in our App Store search and included for review. Tobacco Free Teens rated highly on the MARS quality score in our study (4.16 of 5), in line with Robinson et al.’s finding that this app rated highly on adherence to the US Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence (8 of 11; [3]) and whether the app had adolescent-specific content (scoring 4 of 4). The other adolescent app identified by Robinson et al. in their App Store search was quitSTART, which was returned in our App Store search, but was excluded because the app did not mention youth or teens in the description. quitSTART is an app originally developed by smokefree.gov that was found by Robinson et al. to rate highly on adherence to clinical practice guidelines (8 of 11) and adolescent-specific content (4 of 4), further emphasizing the need for improvements in App Store indexing to help users identify quality, evidence-based tobacco content for the youth. Finally, the Robinson et al. review also reported on a general audience app, Smokerstop, identified from their Google Play search, which overlaps with Smokerface, identified in our literature search, an app available from the same developer but targeted to the youth.

These study findings should be interpreted in light of the following limitations. First, as with any review, we are limited by the parameters of our searches of the literature and App Store. Regarding search dates, interesting new studies testing tobacco-related digital technology for the youth are more recently available, such as a feasibility clinical trial of smokeSCREEN, a tablet-based videogame targeting tobacco product use among the youth [49]. Our search terms may have missed additional relevant work; for example, a feasibility study of an adolescent version of the app Craving to Quit, which uses mindfulness training for smoking cessation [50], was not returned in our PubMed search. Our search terms also did not specify tobacco products nor did we include other synonyms for quit (e.g., “stop” or “cessation”) that the youth may be more likely to use. Additionally, we capped the App Store search at 20 apps per search term. Although there is precedent for this approach [21•], apps lower down in search results were not evaluated. The App Store indicates that search results are ranked based on several factors including text relevance or matches for the app’s name, keywords, and primary category and user behavior, such as downloads as well as quality and quantity of ratings and reviews. While our search terms were based on previous literature and expanded to address the study aims, additional search terms, such as those generated by youth, parents, educators, or healthcare providers seeking tobacco prevention and cessation apps, should be considered. We also note that we did not code or evaluate app features beyond those classified by the MARS. Other reviews have used other useful systematic frameworks for app evaluation [51] or assessed apps for adherence to clinical practice guidelines for tobacco and adolescent-specific content [11].

One important area for future research is the use of text messages for tobacco use prevention and intervention among the youth, including the potential for text messaging to augment tobacco apps. In general, many smartphone apps are only used once after installation, if at all [52]. There is a strong evidence base for text messaging as a behavior change modality broadly, and for quitting tobacco specifically [53], especially among the youth [54]. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that texting may move adults who smoke to quit quicker than smartphone apps [55]. Thus, integration of the two modalities may be most impactful. Moreover, youth smoking cessation apps (and smoking cessation interventions more generally) are likely to be most effective if they are tailored to the unique needs of their intended audience. For example, Native American and Alaska Native youth have the highest prevalence and lowest quit rates of cigarette smoking of all US ethnic groups [56], largely due to the lack of culturally appropriate smoking cessation programs that acknowledge the distinction between ceremonial/sacred and commercial tobacco use [57]. There is a pressing need for future research on youth-focused tobacco prevention and cessation efforts to consider the diversity in tobacco use motives to most effectively target harmful tobacco use and reduce health disparities in tobacco-related health outcomes.

Conclusion

This study aimed to identify and review apps delivering tobacco content directed at the youth, from both the scientific literature and App Store. Consistent with prior reviews, we identified a disconnect between apps that are readily accessible and those that have an evidence base. Similarly, several apps that were highly rated in the App Store received low quality scores, and apps that received high quality scores had a low number of user reviews in the App Store. Findings highlight the need for a better integration of evidence-based and readily available apps directed at youth tobacco use.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco use 2000-2025, fourth edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

USDHHS. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: a report of the surgeon general - PubMed [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2023 Feb 7]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22876391/. Accessed 17 Sep 2023

Mayhew KP, Flay BR, Mott JA. Stages in the development of adolescent smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;1(59 Suppl 1):S61-81.

Reitsma MB, Flor LS, Mullany EC, Gupta V, Hay SI, Gakidou E. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and initiation among young people in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(7):e472–81.

• Office of the Surgeon General. HHS.gov. Preventing tobacco use among youths, surgeon general fact sheet. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/reports-and-publications/tobacco/preventing-youth-tobacco-use-factsheet/index.html. 2017 [cited 2023 Apr 16]. Accessed 17 Sep 2023. This report presents strategies for tobacco prevention and cessation among young people.

CDC. Surgeon general’s advisory on e-cigarette use among youth [Internet]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/surgeon-general-advisory/index.html. 2018 [cited 2023 Mar 20]. Accessed 17 Sep 2023

Struik LL, Dow-Fleisner S, Belliveau M, Thompson D, Janke R. Tactics for drawing youth to vaping: content analysis of electronic cigarette advertisements. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e18943.

• FDA. Results from the Annual National Youth Tobacco Survey. FDA [Internet]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/youth-and-tobacco/results-annual-national-youth-tobacco-survey. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 21]. Accessed 17 Sep 2023. The above paper reports on recent trends in adolescent tobacco use.

Kasza KA, Tang Z, Xiao H, Marshall D, Stanton C, Gross A, et al. National longitudinal tobacco product discontinuation rates among US youth from the PATH Study: 2013–2019 (waves 1–5). Tob Control [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 22]. Available from: https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2023/04/11/tc-2022-057729. Accessed 17 Sep 2023

USDHHS. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 Update [Internet]. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008 [cited 2023 Apr 11]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63952. Accessed 17 Sep 2023

Frey RM, Xu R, Ilic A. Mobile app adoption in different life stages: an empirical analysis. Pervasive Mob Comput. 2017;1(40):512–27.

Stanton A, Grimshaw G. Tobacco cessation interventions for young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 8:CD003289.

Honeyman M, Maguire D, Evans H, Davies A. Digital technology and health inequalities: a scoping review. Cadiff Public Health Wales NHS Trust [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2023 Aug 21]. Available from: https://health-inequalities.eu/jwddb/digital-technology-and-health-inequalities-a-scoping-review-wales/. Accessed 17 Sep 2023

Milton MH, Maule CO, Yee SL, Backinger C, Malarcher AM, Husten CG. Youth tobacco cessation; a guide for making informed decisions.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (U.S.). Office on Smoking and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.), Youth Tobacco Cessation Collaborative, American Legacy Foundation, Canadian Tobacco Control Research Initiative (CTCRI), editors. 2004. Available from: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/11319. Accessed 17 Sep 2023

Statista. Statista. Percentage of teenagers in the United States who have access to a smartphone at home as of April 2018, by household income of parents. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/256544/teen-cell-phone-and-smartphone-ownership-in-the-us-by-household-income/. 2018 [cited 2023 Feb 7]. Accessed 17 Sep 2023

Russell MA, Gajos JM. Annual research review: ecological momentary assessment studies in child psychology and psychiatry. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020;61(3):376–94.

Onken LS, Carroll KM, Shoham V, Cuthbert BN, Riddle M. Reenvisioning clinical science: unifying the discipline to improve the public health. Clin Psychol Sci J Assoc Psychol Sci. 2014;2(1):22–34.

Haskins BL, Lesperance D, Gibbons P, Boudreaux ED. A systematic review of smartphone applications for smoking cessation. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(2):292–9.

Abroms LC, Lee Westmaas J, Bontemps-Jones J, Ramani R, Mellerson J. A content analysis of popular smartphone apps for smoking cessation. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(6):732–6.

Vilardaga R, Casellas-Pujol E, McClernon JF, Garrison KA. Mobile applications for the treatment of tobacco use and dependence. Curr Addict Rep. 2019;6(2):86–97.

• Robinson CD, Seaman EL, Grenen E, Montgomery L, Yockey RA, Coa K, et al. A content analysis of smartphone apps for adolescent smoking cessation. Transl Behav Med. 2018;10(1):302–9. The current manuscript updates and expands on the study cited above.

Milano M. Android Authority. US teens still overwhelmingly love Apple and Google needs to stop ignoring that. Available from: https://www.androidauthority.com/teens-prefer-apple-3149997/. 2022 [cited 2023 Mar 20]. Accessed 17 Sep 2023

Hoeppner BB, Hoeppner SS, Seaboyer L, Schick MR, Wu GWY, Bergman BG, et al. How smart are smartphone apps for smoking cessation? A content analysis. Nicotine Tob Res Off J Soc Res Nicotine Tob. 2016;18(5):1025–31.

Terhorst Y, Philippi P, Sander LB, Schultchen D, Paganini S, Bardus M, et al. Validation of the mobile application rating scale (MARS). PLoS ONE. 2020;15(11):e0241480.

Duncan LR, Hieftje KD, Pendergrass TM, Sawyer BG, Fiellin LE. Preliminary investigation of a videogame prototype for cigarette and marijuana prevention in adolescents. Subst Abuse. 2018;39(3):275–9.

Brinker TJ, Seeger W, Buslaff F. Photoaging mobile apps in school-based tobacco prevention: the mirroring approach. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(6):e183.

Bruce Baskerville N, Wong K, Shuh A, Abramowicz A, Dash D, Esmail A, et al. A qualitative study of tobacco interventions for LGBTQ+ youth and young adults: overarching themes and key learnings. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):155.

Cordova D, Munoz-Velazquez J, Mendoza Lua F, Fessler K, Warner S, Delva J, et al. Pilot study of a multilevel mobile health app for substance use, sexual risk behaviors, and testing for sexually transmitted infections and HIV among youth: randomized controlled trial. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 2020;8(3):e16251.

Kapitány-Fövény M, Vagdalt E, Ruttkay Z, Urbán R, Richman MJ, Demetrovics Z. Potential of an interactive drug prevention mobile phone app (once upon a high): questionnaire study among students. JMIR Serious Games. 2018;6(4):e19.

Palmer AM, Tomko RL, Squeglia LM, Gray KM, Carpenter MJ, Smith TT, et al. A pilot feasibility study of a behavioral intervention for nicotine vaping cessation among young adults delivered via telehealth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;1(232):109311.

Santa Maria D, Padhye N, Businelle M, Yang Y, Jones J, Sims A, et al. Efficacy of a just-in-time adaptive intervention to promote HIV risk reduction behaviors among young adults experiencing homelessness: pilot randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(7):e26704.

Uribe-Madrigal RD, Gogeascoechea-Trejo MDC, de Mota-Morales ML, Ortiz-Chacha CS, Salas-García B, Romero-Pedraza E, et al. Secondary school students’ perceptions of a mobile application design for smoking prevention. Tob Prev Cessat. 2021;7:24.

Schwinn TM, Fang L, Hopkins J, Pacheco AR. Longitudinal outcomes of a smartphone application to prevent drug use among hispanic youth. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2021;82(5):668–77.

Lawn S, Van Agteren J, Zabeen S, Bertossa S, Barton C, Stewart J. Adapting, pilot testing and evaluating the Kick.it app to support smoking cessation for smokers with severe mental illness: a study protocol. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(2):254.

Arrington-Sanders R, Hailey-Fair K, Wirtz A, Cos T, Galai N, Brooks D, et al. Providing unique support for health study among young Black and Latinx men who have sex with men and young Black and Latinx transgender women living in 3 urban cities in the United States: protocol for a coach-based mobile-enhanced randomized control trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9(9):e17269.

Bauermeister JA, Golinkoff JM, Horvath KJ, Hightow-Weidman LB, Sullivan PS, Stephenson R. A multilevel tailored web app-based intervention for linking young men who have sex with men to quality care (get connected): protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2018;7(8):e10444.

Haug S, Castro RP, Wenger A, Schaub MP. Efficacy of a smartphone-based coaching program for addiction prevention among apprentices: study protocol of a cluster-randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1910.

Birrell L, Furneaux-Bate A, Chapman C, Newton NC. A mobile peer intervention for preventing mental health and substance use problems in adolescents: protocol for a randomized controlled trial (the Mind Your Mate study). JMIR Res Protoc. 2021;10(7):e26796.

Garcia LC, Vogel EA, Prochaska JJ. Tobacco product use and susceptibility to use among sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. Prev Med. 2021;145:106384.

Glasser AM, Hinton A, Wermert A, Macisco J, Nemeth JM. Characterizing tobacco and marijuana use among youth combustible tobacco users experiencing homelessness – considering product type, brand, flavor, frequency, and higher-risk use patterns and predictors. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):820.

Prochaska JJ, Fromont SC, Wa C, Matlow R, Ramo DE, Hall SM. Tobacco use and its treatment among young people in mental health settings: a qualitative analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(8):1427–35.

Backinger CL, Fagan P, Matthews E, Grana R. Adolescent and young adult tobacco prevention and cessation: current status and future directions. Tob Control. 2003;12(suppl 4):iv46-53.

Farris SG, Zvolensky MJ, Beckham JC, Vujanovic AA, Schmidt NB. Trauma exposure and cigarette smoking: the impact of negative affect and affect-regulatory smoking motives. J Addict Dis. 2014;33(4):354–65.

Davis DR, Bold KW, Kong G, Cavallo DA, Jackson A, Krishnan-Sarin S. Cannabis use among youth who vape nicotine e-cigarettes: a qualitative analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;234:109413.

Seo S, Cho SI, Yoon W, Lee CM. Classification of smoking cessation apps: quality review and content analysis. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 2022;10(2):e17268.

Dynamicare Health Inc. DynamiCare Health. DynamiCare Health digital therapeutic receives FDA breakthrough device designation for treatment of smoking during pregnancy. Available from: https://www.dynamicarehealth.com/news/2022/3/4/dynamicare-health-digital-therapeutic-receives-fda-breakthrough-device-designation-for-treatment-of-smoking-during-pregnancy. 2022 [cited 2023 Apr 5]. Accessed 17 Sep 2023

Dynamicare Health Inc. DynamiCare Health. DynamiCare Health digital therapeutic receives FDA breakthrough device designation for treatment of alcohol use disorder. Available from: https://www.dynamicarehealth.com/news/2023/3/28/dynamicare-health-digital-therapeutic-receives-fda-breakthrough-device-designation-for-treatment-of-alcohol-use-disorder. 2023 [cited 2023 Apr 5]. Accessed 17 Sep 2023

Insel T. Digital mental health care: five lessons from Act 1 and a preview of Acts 2–5. Npj Digit Med. 2023;6(1):1–3.

Bteddini DS, LeLaurin JH, Chi X, Hall JM, Theis RP, Gurka MJ, et al. Mixed methods evaluation of vaping and tobacco product use prevention interventions among youth in the Florida 4-H program. Addict Behav. 2023;141:107637.

Pbert L, Druker S, Crawford S, Frisard C, Trivedi M, Osganian SK, et al. Feasibility of a smartphone app with mindfulness training for adolescent smoking cessation: craving to quit (C2Q)-teen. Mindfulness. 2020;11(3):720–33.

Bold KW, Garrison KA, DeLucia A, Horvath M, Nguyen M, Camacho E, et al. Smartphone apps for smoking cessation: systematic framework for app review and analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25(1):e45183.

Ceci L. Statista. Mobile apps that have been used only once from 2010 to 2019. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/271628/percentage-of-apps-used-once-in-the-us/. 2021 [cited 2023 Apr 5]. Accessed 17 Sep 2023

Whittaker R, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Rodgers A, Gu Y, Dobson R. Mobile phone text messaging and app-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10(10):CD006611.

Villanti AC, West JC, Klemperer EM, Graham AL, Mays D, Mermelstein RJ, et al. Smoking-cessation interventions for U.S. young adults: updated systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(1):123–36.

Buller DB, Borland R, Bettinghaus EP, Shane JH, Zimmerman DE. Randomized trial of a smartphone mobile application compared to text messaging to support smoking cessation. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(3):206–14.

Park-Lee E. Tobacco product use among middle and high school students — United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Sep 7];71. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/mm7145a1.htm. Accessed 17 Sep 2023

Daley CM, Greiner KA, Nazir N, Daley SM, Solomon CL, Braiuca SL, et al. All nations breath of life: using community-based participatory research to address health disparities in cigarette smoking among American Indians. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(4):334–8.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by grants K01DA048135 (LM), U54HL120163 (JLH), 20YVNR35500014 (JLH), K01CA253235 (JKJ), R01ES030743 (EMMG), R01ES027815 (EMMG), and R34AT010365 (KAG). The funding sponsors had no role in study design; data collection, analyses, or interpretation; manuscript preparation; or the decision to publish the results. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding sponsors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. All authors were involved in the literature and App Store searches and app review. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Drs. LM and KG. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Micalizzi, L., Mattingly, D.T., Hart, J.L. et al. Smartphone Apps Targeting Youth Tobacco Use Prevention and Cessation: An Assessment of Credibility and Quality. Curr Addict Rep 10, 649–663 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-023-00524-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-023-00524-0