Abstract

Purpose of Review

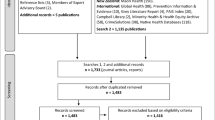

This paper reviews recent research (2013 to 2016) about addictions among Indigenous people. The review concentrates on Indigenous people living within Canada while drawing on literature from countries with similar settler-colonial histories (namely: USA, Australia, and New Zealand).

Recent Findings

Research indicates that Indigenous people, particularly youth, carry a disproportionate burden of harms from problematic substance use in relation to the general population in Canada. While much research continues to focus on the relationship between individualized risk factors (i.e., behaviors) and problematic substance use, increasingly researchers are engaging a social determinants of health framework, including Indigenous-specific determinants. This includes strength-based approaches focusing on protective factors, including the role of traditional culture in Indigenous peoples’ wellness.

Summary

Since focusing on individualized risk factors and deficit-based frames are inadequate for addressing Indigenous peoples’ health, recent research engaging a social determinants of health framework and strength-based approaches is promising.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Writing and researching about addictions among Indigenous peopleFootnote 1 [1, 2] remains a difficult task. Stereotypes casting Indigenous people as inherently prone to addictions, due to genetic vulnerability or cultural norms, are widespread despite research evidence to the contrary [3–7]. For example, in Canada during the 1980s and 1990s, dominant discourses constructed Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) as an “Aboriginal problem” even though “early Canadian studies were limited in scope and methodology” (p. 209) [3]. In response, Indigenous communities and particularly Indigenous women have been subjected to stigma, stereotyping, and surveillance [3, 8–10]. Today, research evidence remains underdeveloped. However, according to the research available, overall, there is not a substantial difference in the prevalence of FASD among Indigenous and non-Indigenous people [11]. At the same time, many Indigenous communities identify substance use as an issue. As such, it is necessary to undertake research about Indigenous peoples’ problematic substance use [12]. How this research should be conducted has become the critical question. Within this paper, we review recent literature (January 2013–January 2016) about problematic substance use among Indigenous people. We focus our review on Canada while drawing on literature from countries with similar settler-colonial histories (namely: USA, Australia, and New Zealand). We first summarize literature on the prevalence of problematic substance use and then focus on addictions through a social determinants of health approach, including Indigenous-specific determinants. Finally, we discuss the recent shift towards strength-based approaches in research with Indigenous people, including the focus on the role of traditional culture in Indigenous peoples’ wellness.

Prevalence and “Risk Factors”

Data specific to addictions and problematic substance use among Indigenous people continues to have significant gaps. Indigenous people are often underrepresented, non-identified in, or excluded from population-based surveys [13•] even though in 2011, 4.3 % of people living in Canada identified as Indigenous [14]. In response to these exclusions and other problematic research practices, First Nations developed the First Nations Regional Health Survey (FNRHS). The second phase of the FNRHS was completed in 2010 [12]. However, culturally-relevant health data for Indigenous people living off-First Nations remains limited [15].

Although directly comparing health indicators among Indigenous and non-Indigenous people can be a barrier to understanding etiologies and impacts, Firestone and Tyndall [13•] recently published a comprehensive review indicating that Indigenous people, and particularly youth, carry a disproportionate burden of harms from problematic substance use. In particular, heavy drinking (5 + drinks in a sitting) was higher and the rate of mortality associated with alcohol use was nearly twice as high among Indigenous people as among the general Canadian population. The use of illicit drugs was also higher as were the associated harms, particularly, Indigenous people were more likely to develop acute hepatitis C and contract HIV. Similarly, Fortin and Bélanger [16] analyzed data gathered through the Santé Québec Health Survey (1992) and the Nunavik Inuit Health Survey Qanuippitaa (2004) and identified that in 2004, a higher proportion of Inuit people living in northern Quebec reported drinking alcohol in the past year (76.9 %) than in 1992 (60.3 %). In comparison to the general population in southern Quebec, a higher proportion of Inuit people living in northern Quebec who reported drinking in the past year also reported at least one episode of heavy drinking. Illicit drug use also increased between 1992 (36.5 %) and 2004 (60.3 %) and is higher among Inuit people living in northern Quebec than among the general Canadian population (14.5 %) according to the 2004 Canadian Addiction Survey findings.

What is often left out of these discussions is that Indigenous peoples’ rates of abstinence from alcohol are higher than non-Indigenous Canadians. For instance, according to the 2007 to 2010 Canadian Community Health Surveys, 34 % of Inuit and 29 % of First Nations people did not drink alcohol in the past year in comparison to 24 % of non-Indigenous people [17]. Similarly, Fortin et al. [16] analysis revealed that a significantly lower proportion of Inuit people living in northern Quebec reported drinking alcohol in the past year (76.9 %) in comparison to the general population in Canada (80.5 %) and Quebec (84.9 %). Further, recent research from the USA, comparing alcohol use among Native American people and White American people indicated that Native Americans abstained more than White Americans and participated in heavy drinking at a similar rate to White Americans [5].Footnote 2

We bring our focus next to Indigenous people affected by HIV to highlight the limitations of approaching problematic substance use and the harms of substance use through individualized “risk factors.” The growing number of Indigenous people who have contracted HIV through intravenous drug use is of increasing concern among researchers and policy-makers. As noted earlier, approximately 4.3 % of people living in Canada identify as Indigenous [14] and according to the Public Health Agency of Canada [18], in 2013, Indigenous people comprised 15.9 % of newly reported cases of HIV. Further, among women who were recently diagnosed with HIV, 32.0 % identified as Indigenous. While across Canada, the proportion of newly diagnosed HIV cases due to intravenous drug use has been decreasing [19],Footnote 3 significant regional and racializedFootnote 4 differences remain [20]. Approximately half of the newly diagnosed HIV cases among Indigenous people were attributed to intravenous drug use. Further, 55 % of the newly diagnosed cases in Saskatchewan were attributed to intravenous drug use and Indigenous people comprised 68 % of the newly diagnosed cases of HIV in the province [18, 21]. While much research literature focuses the conversation around HIV risk behaviors, Negin and Aspin’s [22•] review of research literature draws out the relationship between risk behaviors (such as involvement in sex work, inconsistent condom use or not using condoms, and sharing intravenous drug equipment) and substance use, childhood abuse, domestic violence, social relationships, mistrust of health services, and colonization.

More broadly, until recently, research about problematic substance use and associated harms among Indigenous people has been dominated by epidemiological studies analyzing the relationship between individualized “risk factors,” such as personality traits, behaviors, and substance use and addictions [13•, 22•, 23]. These types of studies continue [13•, 18, 21, 23]. However, wider calls for researchers to address the social determinants of health (SDoH), conduct research from strength-based approaches grounded in Indigenous frameworks, and to work collaboratively with Indigenous communities have shifted the research landscape [24–29, 30•]. Next, this paper reviews literature exploring the relationship between SDoH and addictions among Indigenous people.

Moving Beyond Individualized “Risk Factors”: Social Determinants of Health

Addressing the SDoH for Indigenous people in Canada requires an acknowledgement of the conditions and broader social structures that impact health dynamics [30•]. SDoH recognize the context of particular health disparities, rather than categorizing differences in lived experience through individualized “risk factors”. SDoH specific to Indigenous peoples are identified by Greenwood and de Leeuw [30•] to include geographic, economic, historical, narrative and genealogical, and structural determinants that “are unique because they interface with and are impacted by colonialism” (p. xiii). To illustrate, Indigenous writer Max Fineday explored in a public series what the social determinants of health mean through an Indigenous lens. He wrote: “When hundreds of people gather in spaces across Canada to tell the story of young First Nations people walking to Ottawa to demand that a school be built in their community, when people come together with a single voice to insist that children born on reserve should not have to wait in hospital while the provincial and federal governments bicker about who should pay for their home care, they are speaking the language of the social determinants of health” (para 12) [31].

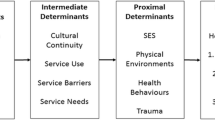

The work of Reading [32] identifies three levels of determinants of health referred to in other SDoH literature [33–35]. Reading uses a tree as a descriptor to highlight proximal, intermediate, and distal determinants as well as their relationships. Shaping health in “the most obvious and direct ways” are proximal determinants (p. 4), which include early child development, income and social status, education and literacy, social support, employment, working conditions, the physical environment, culture, and gender. Intermediate determinants shape health in relation with proximal and distal determinants of health. Intermediate determinants include health care and health promotion, education and justice, government and private enterprise. Some intermediate determinants specific to Indigenous frameworks include the following: relationships with land, language, and ceremony and kinship networks. Distal determinants include the historical, political, ideological, economical, and social structures that shape the intermediate and proximal determinants. Reading illustrates how the rooted system of colonialism in Canada presents many social barriers for achieving health equity, stating “inequities in human health frequently result from corruption or deficiencies in the unseen but critical root system” (p. 5) [32]. As Nathoo and Poole [36] argue these barriers can prevent responsive uptake of public health awareness messaging (i.e., changing health practices).

The interaction between proximal, intermediate, and distal determinants of health (including Indigenous-specific SDoH) and how these interactions contribute to Indigenous peoples’ rates and experiences of substance use and addictions requires further exploration. Shahram’s [35] systematic review on literature about social determinants of Indigenous women’s substance use illustrates this gap. The limited research available focused on Indigenous women’s substance use during pregnancy has a narrow view of determinants of health and is dominated by studies using quantitative methods, which critically limits the scholarship. The research reviewed by Shahram identified that SDoH “are important factors in understanding substance use among Aboriginal women,” and that socio-demographics, trauma, gender, social environments, colonialism, culture, and employment conditions shape Indigenous women’s substance use (p. 15). Similarly, there is a problematic gap in the research about gender- and sexually diverse Indigenous people with gendered analyses most often assuming and perpetuating the gender binary of male/female [37, 38]. A recent study suggests addiction-service needs of Indigenous people who identify beyond the gender binary of male/female remain largely unmet and further research is required to understand barriers specific to this population [39].

Some researchers have examined how certain intermediate determinants of health (child welfare system, justice system, and drug policy) are influenced by distal determinants of health, and shape Indigenous peoples’ substance use and the health of Indigenous people who use substances [10, 40–43]. Tracking the history, present policies and practices of this system (and its relation to social, political, and economic systems or distal determinants) over time can foster further understanding of addictions among Indigenous people. For instance, Marshall [41] analyzed the Canadian 2012 National Anti-Drug Strategy pillars (enforcement, prevention, and treatment) and associated action plans. This analysis connects Indigenous peoples’ over-representation in the criminal justice system, higher rates of blood-born infection related to injection drug use, and higher rates of reported illicit substance use among youth to the drug-related harms and structural violence that are the result of Canadian government policies regarding illicit substances (p.1).

Indigenous-specific intermediate determinants of health are receiving more attention with increasing calls from Indigenous communities, organizations, and scholars to account for the relationship among traditional cultural practices, problematic substance use, addictions, and addictions treatment and healing. Some researchers are exploring the complex relationship between Indigenous culture and substance use and addiction. For instance, Twyman and Bonevski [44] suggest that due to the ceremonial and cultural significance of tobacco for many Indigenous nations, smoking cessation initiatives may pose unique barriers for individuals by challenging family and community relationships or, as was perceived in some cases, “exclud[ing] an individual from fully participating in their culture” (p. 7) [44]. However, traditional cultural practices can also offer protection and resilience for Indigenous people against problematic illicit and prescription drug use [45], for Indigenous youth who are using illicit drugs [46], and in other circumstances. For instance, Rowan et al.’s [47•] scoping study found that “the culture-based interventions used in addictions treatment for Indigenous people are beneficial to help improve client functioning in all areas of wellness” (p.1).

Efforts by epidemiologists to consider Indigenous-specific SDoH when working with Indigenous people around addictions holds promise if there is a community contextualization of epidemiological data analyzing the relationship between SDoH and substance use and addictions (particularly Indigenous-specific SDoH). This is necessary to avoid misrepresentation and also fosters relationships between Indigenous people and addiction researchers [24, 48, 49]. For instance, in Ryan and Cooke’s [50] statistical analysis of the Aboriginal Peoples Survey and Métis supplement data, the authors identified that Métis people who spoke an Indigenous language or lived in a house where an Indigenous language was spoken were more likely to currently smoke. While the authors acknowledged that this relationship “might be explained by social factors not captured in the models” (p. e275), as King [24] suggests, epidemiological studies such as this one should engage experts “with the requisite contextual knowledge—Métis community knowledge holders in this case—to guide the data interpretation” (p. 457).

Above, we have focused on research exploring the intermediate and distal determinants of health and their interrelationship; however as Reading [32] points out, research that analyzes SDoH most often focuses on the proximal determinants. Analyzing substance use and addictions in relation to the constellation of proximal, intermediate, and distal determinants shaping Indigenous peoples’ health will prompt more necessarily complex understandings and responsive policy and programming. Research focusing on proximal determinants of Indigenous peoples’ health often illustrate patterns among a group of people or a population, but not the larger social, economic and ideological conditions that shape these patterns. As a result, focus on the proximal determinants of health contributes to the pathologization of Indigenous people. For instance, much research demonstrates that overall, Indigenous people have lower incomes than non-Indigenous people living in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand [51]. Further, research suggests this pattern contributes to the health disparities Indigenous people face [22•, 35, 50]. The political, social, economical, and ideological systems, including colonial policies that contribute to these inequalities make it difficult for people living on lower incomes to access what they need to be healthy. In Canada, the USA, Australia, and New Zealand, poverty and addictions are largely viewed as a personal failing of character; therefore, lower incomes and higher rates of substance use among Indigenous people are largely interpreted as the fault and responsibility of Indigenous people rather than the ideological, social, and economic systems [41, 52–54]. Examining how these shifting political and economic conditions interact with current and historical colonial policies to place Indigenous people “at risk” of problematic substance use and related harms is necessary.

As we have demonstrated above, the dominant focus on proximal determinants of health still frames Indigenous people through a deficit-based, Western lens that pathologizes Indigenous people dealing with addictions. This is highly problematic due to the stigma surrounding people dealing with addictions, particularly Indigenous people dealing with addictions. In addition to analyzing the complex relationships between proximal, intermediate, and distal determinants of Indigenous peoples’ health, increasingly, researchers working with Indigenous communities to understand and address addictions are resisting stigma by refocusing on strength-based and Indigenous approaches to wellness and healing.

Indigenous Traditional Culture: Resistance, Resiliency, and Healing

Indigenous focused research over the past decade in Canada has increasingly concentrated on the protective and healing role of cultural practices and beliefs. This has been evident in formal research funding calls from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Canada’s major health research funding body, through to work by Indigenous-led non-governmental organizations. Most notable to the addictions field, in 2011, the Thunderbird Partnership Foundation (TPF) (formerly the National Native Addictions Partnership Foundation) released Honouring Our Strengths: A Renewed Framework to Address Substance Use Issues among First Nations in Canada. This community developed report recommends the establishment of a culturally competent evidence base to document and demonstrate the effectiveness of cultural interventions offered by the National Native Alcohol and Drug Abuse Program (NNADAP) and the Youth Solvent Addiction Program (YSAP) [55]. NNADAP and YSAP are the primary modes of addictions treatment for First Nations and Inuit people in Canada; funded by Health Canada and controlled by First Nations and Inuit communities and organizations, there are 52 residential NNADAP treatment centers offering over 550 prevention programs across the country and 10 YSAP residential centers.

Cultures and cultural identity is understood by Indigenous peoples, and particularly Elders and traditional knowledge keepers in Canada and elsewhere, as fundamental to individual and communal health and wellness and is one of the Indigenous-specific SDoH identified by Reading [32, 47•, 56–59]. Emphasizing the strengths of Indigenous cultures resists colonial processes, which have dismissed, demonized, and even criminalized (from 1879 to 1951) Indigenous cultural practices in Canada [2]. Indeed, research and practice have largely prioritized attention to Indigenous health “deficits” in relation to non-Indigenous people; framing Indigenous people in terms of “lack” and “deficits” is congruent with colonial discourses. It is only recently that Indigenous cultures’ inherent strengths have become a focus within social science and health research, a shift that Indigenous academics and community members have long been advocating for.

Part of the shift towards strength-based approaches was the earlier work of academics such as Kirmayer and Valaskakis [29] and colleagues about the Western-derived concept of resiliency, and the need to reconceptualize it from an Indigenous perspective [60]. Kirmayer relates:

“Aboriginal Peoples in Canada have diverse notions of resilience grounded in culturally distinctive concepts of the person that connect people to community and the environment, the importance of collective history, the richness of Aboriginal languages and traditions, as well as individual and collective agency and activism” (p. 84).

Chandler’s work over time has likewise identified the relationship between culture and identity, understood at both the individual and communal level, as a protective factor for suicide within First Nations [59]. The work of Wilkes and Gray [61] in Australia similarly makes clear this linkage, as well as the relationship between suicide and substance misuse. Further, at a recent meeting of the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention’s American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) Task Force, two of the future directions identified include the following: (a) the need to emphasize protective factors, resilience and well-being and (b) committing to Indigenous approaches to inquiry [62].

Current community-led work in Canada focuses on individual and communal strengths grounded in cultural practices and connection. The First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework, for example, is an initiative led by the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch/Health Canada, the Assembly of First Nations and Indigenous Mental Health leaders from various non-government organizations. It proposes a strength-based model for mental wellness, including addictions; “Culture is the heart of the framework, emphasizing First Nations strengths and capacities. It identifies a continuum of services needed to promote mental wellness and provides advice on policy and program changes that will enhance First Nations mental wellness outcomes” [63]. Such work is grounded in past research addressing the health disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people as well as the relevance and importance of cultural knowledge [28, 29, 47•, 59]. The role of cultural practices and teachings in addictions treatment for Indigenous peoples has been documented in Canada and elsewhere [47•, 64–67]. In Owen’s [66] review of Native American recovery programs in the USA, she states, “Rather than focusing on each client as a disconnected individual, Native-led treatment centres also make an effort to focus on the ‘self in community’, with its history, culture and social relations.” (p. 1047). An example is the Wellbriety program based on the traditional Medicine Wheel and integrated with the 12-step program framed as an interconnected circle of teachings [68].

Strength-based efforts highlighting the importance of culture, and led by Indigenous community organizations and cultural knowledge keepers, are also present within academic research. There has been growing attention towards Indigenous and decolonizing methodologies over the past two decades [25, 27, 69–71]. Drawing on this understanding, some describe the research process as ceremony [72] and emphasize its potential for cultural renewal [48]. To illustrate, in response to the Honouring Our Strengths renewed framework and a funding call from CIHR, the Thunderbird Partnership Foundation initiated a project with the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), and the University of Saskatchewan (U of S), titled Honouring Our Strengths: Indigenous Culture as Intervention in Addictions Treatment. The aim of the study was to develop a measure that would demonstrate the efficacy of cultural interventions in NNADAP and YSAP treatment programs. As shared by the team on the tool’s development, “In plain language, our project team wanted to develop an assessment that centered and reflected the culturally-based programming offered to clients at NNADAP and YSAP treatment centers. Evaluating outcomes with deficit-based assessments did not demonstrate the efficacy of these programs or meet the needs of clients” [73] The outcome was the Native Wellness Assessment™, which is designed to be used with Indigenous people to explore from an Indigenous cultural perspective the client’s state of wellness at a specific point in time. A workbook and facilitator’s manual was also developed, based on this culturally-based understanding of wellness, and offers individual and/or group exercises for engaging with culturally-based supports for wellness. This project reflects the focus of other emerging community-based academic research foregrounding Indigenous knowledge and decolonizing methodologies [74–78].

Calls from Indigenous communities and scholars to recognize the role of Indigenous cultural knowledge and practices in Indigenous health and well-being, along with movements to decolonize research and the academy have disrupted traditional academic dynamics. Indigenous academics and community members have an increasing presence on health and social science research teams, including Indigenous knowledge keepers who guide research processes, including whether and how cultural knowledge will be shared. For instance, the Honouring our Strengths project included an Indigenous knowledge group of elders and knowledge keepers “dedicated to ensuring that the information gathered remained rooted in Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing” [48]. When working to foreground Indigenous cultural knowledge, it is necessary to center the voices of Indigenous people. Research practices are changing and we await forthcoming publications to fully understand the impact of this methodological shift.

Crucial to the addictions and other health-related work shared above is the lead role of Indigenous-based organizations in the development of both guiding frameworks and research processes that foreground culture and are strength-based. In some ways, institutions, such as research funding bodies, are transitioning to support this approach in Canada. For example, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Institute of Aboriginal Peoples’ Health, has adopted the concept of “two-eyed seeing” [79]. Two-eyed seeing is expressed as “To see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous ways of knowing, and to see from the other eye with the strengths of Western ways of knowing, and to use both of these eyes together” (p. 335) [80]. As a guiding concept, two-eyed seeing originated in the work of Mi’kmaq Elders Murdena and Albert Marshall from Eskasoni First Nation, along with Dr. Cheryl Bartlett [81]. However, the Canadian government who was in power from 2006 until 2015 undermined Indigenous peoples’ health and wellness in numerous other ways while they were in power, introducing moralistic, enforcement-focused drug policy [41], cutting the social safety net [82], and undermining treaty rights [83]. With the recent change of federal leadership and commitments to address longstanding disparities in funding and services in the country, many of which are related to addictions, supportive and respectful policy changes seem more possible. Key commitments include initiating an inquiry on missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in Canada and implementing all 94 calls to action in Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission report [84],Footnote 5 which according to the Chair, Justice Murray Sinclair, marks the start of the new era and reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada [85]. In the USA, Australia, and New Zealand, there are also examples of profound disregard (as well as respect and support) for Indigenous people and the role of Indigenous cultures in healing.

Conclusion

This review summarizes literature published between 2013 and 2016 about problematic substance use among Indigenous populations in Canada. Research literature has largely ignored Indigenous health or viewed it through a Western, deficit-based frame. Promising is researchers increasing engagement with a social determinants of health framework, including Indigenous-specific determinants, and shifts towards strength-based approaches to understand problematic substance use among Indigenous people, particularly researchers’ focus on protective factors rooted in Indigenous cultural practices and beliefs. Healthcare practitioners can engage social determinants of health framework to more effectively support individual clients’ health, particularly clients who are problematically using substances, and to advocate for supportive policy changes. As a community, we need to continue to push for research and practice that (1) engages Indigenous-specific determinants and (2) addresses the relationship between proximal, intermediate and distal determinants, as well as (3) centers community-based Indigenous knowledge and Indigenous approaches to wellness. It will be important to track shifts over time and continue to follow the lead of Indigenous organizations and leadership.

Notes

In this paper, Indigenous people refers to those who are the original inhabitants of the land we are discussing. Within Canada, Indigenous people include First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people.

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System uses “White” as a racial/cultural group and a racial/ethnic group.

According to the 2012 Canadian Alcohol and Drug Use Monitoring Survey, this is not due to substantial decreases in illicit drug use.

As Browne, Smye explain, “Racialization is a process of attributing social, economic, and cultural differences to race. Racialization may be conscious and deliberate (an act of racism that discriminates openly) or unconscious and unintended. It takes its power from everyday actions and attitudes and from institutionalized policies and practices that marginalize individuals and collectivities on the basis of presumed biological, physical or genetic differences.” [18] As such, health disparities that are often labeled “racial” are produced through processes of racialization.

“To the Commission, reconciliation is about establishing and maintaining a mutually respectful relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples in this country. In order for that to happen, there has to be an awareness of the past, acknowledgement of the harm that has been inflicted, atonement for the causes, and action to change the behavior” (pp. 6 and 7)

References

Papers of Particular Interest, Published recently, Have Been Highlighted as: • Of importance

United Nations. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. United Nations, 2008 March 2008. Report No.: Contract No.: 07–58681.

Canada. Report of the Royal Commission on aboriginal peoples. Ottawa: ONT: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada; 1996.

Tait C. Disruptions in nature, disruptions in society: Aboriginal peoples of Canada and the ‘making’ of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. In: Kirmayer LJ, Valaskakis GG, editors. Healing Traditions: The mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada Vancouver: . Vancouver: UBC Press; 2009. p. 196–218.

Tait C. Simmering outrage during an “epidemic” of fetal alcohol syndrome. Canadian Woman Studies/les Cahiers de la Femme’s. 2008;26(3/4):69–76.

Cunningham JK, Solomon TA, Muramoto ML. Alcohol use among Native Americans compared to whites: examining the veracity of the ‘Native American elevated alcohol consumption’ belief. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;160:65–75.

Dell C, Gardipy J, Kirlin N, Naytowhow V, Nicol JJ. Enhancing the well-being of criminalized indigenous women: a contemporary take on traditional and cultural knowledge. In: Balfour G, Comach E, editors. Criminalizing women: gender and (in)justice in neo-liberal times. Blackpoint, NS: Fernwood Publishing; 2014. p. 314–29.

Hunting G, Browne AJ. Decolonizing policy discourse: reframing the ‘problem’ of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Women’s Health and Urban Life. 2012;11(1):35–53.

Rutman D, Callahan M, Jackson S, Field B. Substance Use and Pregnancy: Conceiving Women in the Policy-Making Process. Ottawa, ON: Status of Women Canada, 2000 Catalogue No.: SW21-47/2000E.

Salmon A. “It takes a community”: constructing aboriginal mothers and children with FAS/FAE as objects of moral panic in/through a FAS/FAE prevention policy. Journal of the association for research on mothering. 2004;6(1):112–23.

Baskin C, Strike C, McPherson B. Long time overdue: an examination of the destructive impacts of policy and legislation on pregnant and parenting aboriginal women and their children. The International Indigenous Policy Journal [Internet]. 2015; 6(1). Available from: http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/iipj/vol6/iss1/5.

Ospina M, Dennet L. Systematic review on the prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Institute of Health Economics: Edmonton, AB; 2013.

First Nations Information Governance Centre. First Nations Regional Health Survey (RHS) 2008/10: national report on adults, youth and children living in first nations communities. Ottawa: FNIGC; 2012.

Firestone M, Tyndall M, Fischer B. Substance use and related harms among aboriginal people in Canada: a comprehensive review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(4):1110–31 .This article is a comprehensive review of public data, journal articles, and grey literature from 2000 to 2014 about substance use and harms among Indigenous people in Canada. The literature reviewed indicates Indigenous people are carrying a disproportiate burden of substance use-related harms

Statistics Canada. Aboriginal peoples in Canada: First Nations People, Métis and Inuit. Ottawa, Ontario 2013. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/access_acces/alternative_alternatif.action?t=99-011-XWE2011001&l=eng&loc=http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-011-x/99-011-x2011001-eng.pdf.

Firestone M, Smylie J, Maracle S, McKnight C, Spiller M, O’Campo P. Mental health and substance use in an urban First Nations population in Hamilton, Ontario. Canadian journal of public health—Revue canadienne de sante publique. 2015;106(6):e375–e81.

Fortin M, Bélanger RE, Boucher O, Muckle G. Temporal trends of alcohol and drug use among Inuit of northern Quebec, Canada. International journal of circumpolar health. 2015;74.

Gionet L, Roshanafshar S. Select health indicators of First Nations people living off reserve, Métis and Inuit. Ottawa, ONT: Statistics Canada, 2013 Catalogue No.: 82–624-X.

Public Health Agency of Canada. HIV and AIDS in Canada: Surveillance report to December 31, 2013. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada, 2014.

Health Canada. Canadian alcohol and drug use monitoring survey: summary of results for 2012. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2014.

Browne AJ, Smye VL, Varcoe C. The relevance of postcolonial theoretical perspectives to research in aboriginal health. The Canadian journal of nursing research =. Revue canadienne de recherche en sciences infirmieres. 2005;37(4):16–37.

Saskatchewan Ministry of Health. HIV and AIDS in Saskatchewan 2013. Regina, SK: Saskatchewan Ministry of Health; 2014.

Negin J, Aspin C, Gadsden T, Reading C. HIV among indigenous people: a review of the literature on HIV-related behavior since the beginning of the epidemic. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(9):1720–34 .This article is a comprehensive review of research about HIV-related behaviours and social determinants of health among Indigenous people in Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand. The authors illustrate the relationship between ‘risk behaviours’ and determinants of health, including colonization

Mushquash CJ, Stewart SH, Mushquash AR, Comeau MN, McGrath PJ. Personality traits and drinking motives predict alcohol misuse among Canadian aboriginal youth. Int J Ment Health Addiction. 2014;12(3):270–82.

King M. Contextualization of socio-culturally meaningful data. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2015;106(6):e457.

Smith LT. Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples. 2nd Ed. Ed. London, UK: Zed Books; 2012.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research, National Sciences and Engineering Research Council, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Chapter 9: Research involving the First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada. In: Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans 2010. 2nd Edition. Available from: http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/pdf/eng/tcps2/TCPS_2_FINAL_Web.pdf.

Walters KL, Antony S, Evans-Campbell T, Simoni JM, Duran B, Schultz K, et al. “Indigenist” collaborative research efforts in native American communities. In: Stiffman AR, editor. The field research survival guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 146–73.

Adelson N. The embodiment of inequity: health disparities in aboriginal Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2005;96(2):S45–61.

Kirmayer LJ, Valaskakis GG. Healing traditions: The mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. Vancouver. 2009

Greenwood M, de Leeuw S, Lindsay NM, Reading C. Determinants of indigenous peoples’ health in Canada: beyond the social. Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars Press; 2015 .This book is the first comprehensive text examining Indigenous people’s determinants of health from Indigenous perspectives

Fineday M. Dreaming healthy Nations: Indigenous stories & the social determinants of health. Upstream [Internet]. 2015 August 3, 2016. Available from: http://www.thinkupstream.net/dreaming_healthy_nations.

Reading C. Structural determinants of aboriginal peoples’ health. In: Greenwood M, de Leeuw S, Lindsay NM, Reading C, editors. Determinants of indigenous peoples’ health in Canada: beyond the social. Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars Press; 2015. p. 3–15.

Walters KL, Spencer MS, Smukler M, Allen HL, Andrews C, Browne T, et al. Health equity: Eradicating health inequalities for future generations. Baltimore, MD: American Academy of Social Work & Social Welfare, 2016 Contract No.: 19.

Smye SL. Reducing racial and social-class inequalities in health: the need for a new approach. Health Aff. 2008;27(2):456–9.

Shahram S. The social determinants of substance use for aboriginal women: A systematic review. Women & health. 2015.

Nathoo T, Poole N, Bryans M, Dechief L, Hardeman S, Marcellus L, et al. Voices from the community: developing effective community programs to support pregnant and early parenting women who use alcohol and other substances. First peoples child & family review. 2013;8(1):93–106.

Hunt S. Embodying self-determination: beyond the gender binary. In: Greenwood M, de Leeuw S, Lindsay NM, Reading C, editors. Determinants of indigenous peoples’ health in Canada: beyond the social. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2015. p. 104–19.

Hall L. Two-eyed seeing in indigenous addiction research and treatment. In: Boyle E, Greaves L, Poole N, editors. Transforming addiction: gender, trauma, transdisciplinarity. New York: Routledge; 2015. p. 69–75.

Scheim AI, Jackson R, James L, Dopler TS, Pyne J, Bauer GR. Barriers to well-being for aboriginal gender-diverse people: results from the trans PULSE project in Ontario, Canada. Ethnicity and Inequalities in Health and Social Care. 2013;6(4):108–20.

Tait C, Henry R, Walker RL. Child welfare: a social determinant of health for Canadian First Nations and Métis children. Pimatisiwin. 2013;11(1):39–53.

Marshall SG. Canadian Drug Policy and the reproduction of Indigenous inequities. The International Indigenous Policy Journal. 2015;6(1).

Baldry E, Cuneen C. Imprisoned indigenous women and the shadow of colonial patriarchy. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology. 2014;47(2):276–98.

Ware S, Ruzna J, Dias G. It can’t be fixed because it’s not broken: racism and disability in the prison industrial complex. In: Ben-Mosche L, Chapman C, Carey AC, editors. Disability incarcerated. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US; 2014. p. 163–84.

Twyman L, Bonevski B, Paul C. Perceived barriers to smoking cessation in selected vulnerable groups: a systematic review of the qualitative and quantitative literature. BMJ Open. 2014;4(e006414):1–15.

Currie CL, Wild TC, Schopflocher DP, Laing L, Veugelers P. Illicit and prescription drug problems among urban aboriginal adults in Canada: The role of traditional culture in protection and resilience. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;88(July 2013).

Pearce M, Jongbloed KA, Richardson CG, Henderson EW, Pooyak SD, Oviedo-Joekes E, et al. The cedar project: resilience in the face of HIV vulnerability within a cohort study involving young indigenous people who use drugs in three Canadian cities. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1095–106.

Rowan M, Poole N, Shea B, Gone JP, Mykota D, Farag M, et al. Cultural interventions to treat addictions in indigenous populations: Finding from a scoping study. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention and Policy. 2014;9(34). This scoping study highlights the important role that culture plays in many Indigenous people’s treatment and recovery from addictions

Hall L, Dell CA, Fornssler B, Hopkins C, Mushquash C. Research as cultural renewal: applying two-eyed seeing in a research project about cultural interventions in First Nations Addictions Treatment. International Indigenous Policy Journal. 2015;6(2).

Dell C, Fillmore C, Kilty JM. Ensuring Aboriginal women's voices are heard: Toward a balanced approach in community-based research. In: Kilty JM, Felices-Luna M, editors. Demarginalizing voices: Commitment, emotional, and action in qualitative research. Vancouver, UBC: UBC Press; 2014. p. 38–61.

Ryan CJ, Cooke MJ, Leatherdale ST, Kirkpatrick SI, Wilk P. The correlates of current smoking among adult Métis: evidence from the aboriginal peoples survey and Métis supplement. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2015;106(5):e271.

Mitrou F, Cooke M, Lawrence D, Povah D, Mobilia E, Guimond E, et al. Gaps in indigenous disadvanage are not closing: a census cohort study of social determinants of health in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand from 1981 to 2006. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:201–10.

Sered SS, Norton-Hawk M, editors. Can’t catch a break: gender, jail, drugs and the limits of personal responsibility. Oakland, CA: University of California Press; 2014.

Moore D, Fraser S, Törrönenb J, Tinghög ME. Sameness and difference: metaphor and politics in the constitution of addiction, social exclusion and gender in Australian and Swedish drug policy. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2015;26(4):420–8.

Beddoe L. Feral families, troubled families: the spectre of the underclass in New Zealand. N Z Sociol. 2014;29(3):51–68.

National Native Addictions Partnership Foundation, Assembly of First Nations, Health Canada. Honouring Our strengths: a renewed framework to address substance use issues among First Nations in Canada. Ottawa, ON: National Native Addictions Partnership Foundation, 2011.

National Native Addictions Partnership Foundation. Indigenous Wellness Framework ©. Honouring our strengths: indigenous culture as intervention in addictions treatment. Bothwell, ON: National Native Addictions Partnership Foundation; 2014.

Mushquash C, Comeaau MN, McLeod B, Stewart S. A four-stage method for developing early interventions for alcohol among aboriginal adolescents. International Journal of Mental Health and Addictions. 2010;8(2):296–309.

Papequash C. The yearning journey: escape from alcoholism. Canada: Seven Generation Helpers Publishing; 2011.

Chandler MJ, Dunlop WL. Cultural wounds demand cultural medicines. In: Greenwood M, de Leeuw S, Lindsay NM, Reading C, editors. Determinants of indigenous peoples’ health in Canada: beyond the social. Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press; 2015. p. 78–89.

Kirmayer LJ, Dandeneau S, Marshall E, Phillips MK, Williamson KJ. Rethinking resiliance from indigenous perspectives. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(2):84–91.

Wilkes E, Gray D, Saggers S, Casey W, Stearne A. Substance misuse and mental health among Aboriginal Australians. In: Purdle N, P. D, Walker P, editors. Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. Barton: Australian Council for Educational research, Kulunga Research Network, Telethon Institute for Child Health Research; 2010. p. 117–33.

Wexler L, Chandler M, Gone JP, Cwik M, Kirmayer LJ, LaFromboise T, et al. Advancing suicide prevention research with rural American Indian and Alaska Native populations. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):891–9.

Assembly of First Nations. First Nations mental wellness continuum framework launched 2015, January 28 [Available from: http://www.afn.ca/en/news-media/latest-news/first-nations-mental-wellness-continuum-framework-launched.

Davey CJ, McShane KE, Pulver A, McPherson C, Firestone M. Ontario Federation of Indian Friendship Centres. A realist evaluation of a community-based addiction program for urban aboriginal people. Alcohol Treatment Quarterly. 2014;32(1):33–57.

Hansen JG, Callihoo N. How the urban aboriginal community members and clients of the friendship centre in Saskatoon understand addictions recovery. Aboriginal Policy Studies. 2014;3(1):88–111.

Owen S. Walking in balance: Native American recovery programs. Religions. 2014;5:1037–49.

Adams C, Arratoon C, Boucher J, Cartier G, Chalmers D, Dell CA, et al. The helping horse: how equine assisted learning contributes to the wellbeing of First Nations youth in treatment for volatile substance misuse. Human-Animal Interaction Bulletin. 2015;1(1):52–75.

White Bison I. The red road to wellbriety in the Native American way. Colorado Springs, CO: Coyhis Publishing; 2002.

Kovach M. Indigenous methodologies: characteristics, conversations, and contexts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2009.

Baydala A, Placsko C, Hampton M, Bourassa C, McKay-McNabb K. A narrative of research with, by, and for aboriginal peoples. Pimatisiwin. 2006;4(1):47–65.

Smith LT. Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples. London: Zed Books; 1999.

Wilson S. Research is ceremony: indigenous research methods. Halifax: Fernwood Pub.; 2008. 144 p. p.

Fornssler B, Hopkins C, Dell C. Sharing culture, promoting strength: The Native Wellness Assessment. Assembly of First Nations Mental Wellness Bulletin [Internet]. Fall 2015: [13-5 pp.]. Available from: http://health.afn.ca/en/highlights/general/afn-mental-wellness-bulletin-fall-2015.

Zavala M. What do we mean by decolonizing research strategies? Lessons from decolonizing, indigenous research projects in New Zealand and Latin America. Decolonization: Indigeneity, education & society. 2013;2(1):55–71.

Flicker S, Danforth JY, Wilson C, Oliver V, Larkin J, Restoule J-P, et al. “Because we have really unique art”: decolonizing research with indigenous youth using the arts. International Journal of Indigenous Health. 2014;10(1):16–34.

Sasakamoose J, Scerbe A, Wenaus I, Scandrett A. First Nation and Métis youth perspectives of health: an indigenous qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry. 2016.

Stevenson SA. Toward a narrative ethics: indigenous community-based research, the ethics of the narrative, and the limits of conventional bioethics. Qualitative Inquiry. 2016.

Flicker S, O'Campo P, Monchalin R, Thistle J, Worthington C, Masching R, et al. Research done in “a good way”: the importance of indigenous elder involvement in HIV community-based research. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(6):1149–54.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Institute of Aboriginal Peoples’ Health. Aboriginal peoples’ wellness in Canada: Scaling up the knowledge. Cultural context and community aspirations 2011. Available from: http://www.integrativescience.ca/uploads/files/2011_Aboriginal_Peoples_Wellness_in_Canada_scaling_up_the_knowledge.pdf.

Bartlett C, Marshall M, Marshall A. Two-eyed seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. Journal of Environmental Studies. 2012;2:331–40.

Iwama M, Marshall M, Marshall A, Bartlett C. Two-eyed seeing and the language of healing in community-based research. Can J Nativ Educ. 2009;32(2):2–23.

Rice JJ, Prince MJ, editors. Changing politics of Canadian social policy. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press; 2013.

Kino-nda-niimi Collective. The winter we danced : voices from the past, the future, and the Idle No More movement 2014. 439 pages p.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada; 2015. Available from: http://www.trc.ca/.

Mas S. Truth and Reconciliation chair says final report marks start of ‘new era’. CBC News [Internet]. 2015, Dec. 15 August 3, 2016. Available from: http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/truth-and-reconciliation-final-report-ottawa-event-1.3365921

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to Indigenous community-based researchers who reviewed and provided expert comments on an earlier draft of this paper: Sharon Acoose, Laura Hall, and Erin Settee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

In the above article, the authors refer to a research project led by the second author. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the Canadian Interagency Advisory Panel on Research Ethics’ standards according to the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (2nd Edition) (TCPS 2), particularly, Chapter 9: Research involving the First Nations, Métis and Inuit Peoples of Canada and with the Indigenous principles of Ownership, Control, Access and Possession (OCAP).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Health Disparities in Addiction

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McKenzie, H.A., Dell, C.A. & Fornssler, B. Understanding Addictions among Indigenous People through Social Determinants of Health Frameworks and Strength-Based Approaches: a Review of the Research Literature from 2013 to 2016. Curr Addict Rep 3, 378–386 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-016-0116-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-016-0116-9