Abstract

This study aimed to examine Chinese college students' engagement and satisfaction with their university learning experience. In particular, the study focused on emotional engagement and how it was associated with student satisfaction. Nationally representative data from the 2012 China College Student Survey (CCSS) which drew from 55 higher education institutions (N = 67,182; 45.6% female) indicated that Chinese students had high levels of emotional engagement. Emotional engagement positively predicted student satisfaction and also moderated the effect of cognitive engagement on satisfaction. Educational implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Chinese hold a firm belief that learning is a process full of pain and suffering. Almost every Chinese child has been told the story of a famous scholar and statesman named Su Qin (380–284 BC), who tied his hair to a house beam and jabbed his side with an awl to stay awake while studying past midnight. Pain and suffering are recognized as necessary to attain success, and there is little regard for positive emotions or enjoyment that might accompany the learning journey. After all, institutions of education are not there to satisfy students, but to educate them.

In recent years, reformers of Chinese education have advocated enjoyment of the learning process as an important aspect of good learning. This reform is rooted in scientific research highlighting the importance of affective factors in cognition and learning (Ashby et al. 1999; Dai and Sternberg 2004; Damasio 2003; Meyer and Turner 2002; Panksepp 2003). Despite the strength of the scientific evidence, many Chinese educators and the general public still harbor some doubt about the need for reforms that emphasize the positive emotional aspects of learning. The contrast of two conceptions, ‘bitter learning’ (苦学) and ‘enjoyable learning’ (乐学), somehow reflects the cultural conflict between the more traditional Chinese culture and modern Western influences.

Given the conflicting views on the role of positive emotions in the learning process, this study aims to empirically examine enjoyment of the learning process or what education researchers termed as emotional engagement in the Chinese university context. We explore the state of Chinese college students’ emotional engagement and investigate how it is associated with key learning outcomes, specifically to student satisfaction. Moreover, we examine the role of emotional engagement in potentially amplifying the relationship between other forms of engagement and student satisfaction.

This study moves the literature forward in several important ways. Research on emotions is rather limited in educational research in China. This study explores the emotional engagement of Chinese college students which has been largely neglected in the Chinese context. It sheds light on the interplay of students’ emotional engagement and satisfaction, and enriches the understanding of the role of emotions on the learning process and outcomes of Chinese college students. This study is also methodologically rigorous. We used nationally representative data from Chinese college students to examine how emotional engagement, in particular, is related to student satisfaction.

Student Engagement

Student engagement has occupied an important place in the higher education lexicon in recent decades (Carini et al. 2006; Kotze and Plessis 2003; Kuh 2006). In the literature, there are two approaches to defining the concept (Coates 2006). One approach is based on Astin’s theory of student involvement, depicting the amount of physical and psychological energy that students devote to educational experiences (Astin 1984, 1985, 1991). Following this approach, student engagement is depicted as a ‘meta’ construct, consisting of three dimensions: behavioral (students’ on-task time, effort, attention, and persistence), cognitive (students’ use of sophisticated strategies of learning, and active self-regulation), and emotional engagement (students’ affective reactions in school, including interest, enjoyment, boredom, sadness, and anxiety) (Fredricks et al. 2004; Jimerson et al. 2003). The other approach is based on Kuh’s (2001) theory, which emphasizes the resources and efforts an institution puts into creating and maintaining a nurturing environment to promote student involvement. Through combining these two approaches, research in student engagement looks into psychological properties of college students, quality and effectiveness of institutions, and the interplay between students and their institutions to explain the learning process of college students and foster their academic learning and success (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2001).

Previous research has presented substantial evidence that student engagement is positively associated with student satisfaction with their learning experience (Abrahamowicz 1988). Astin (1999) argued that students who are intensely focused on their studies tend to isolate themselves due to the time and effort that they are putting into studies but at the same time academic performance counteracts this isolation and these students enjoy considerable satisfaction. This has been identified by studies that strong linkages exist between students’ time, effort, and interest in academic activities and improved performance and satisfaction (Ertl and Wright 2008). In addition, it is reported that students in institutions encouraging active involvement in learning and teaching as well as campus life tend to be more satisfied with their experience (Kuh et al. 1991). Student engagement promotes a sense of identity and belonging and loyalty to the institution (Berger and Milem 1999) which in turn provides a vibrant learning environment and impact on student learning and thus satisfaction with the overall experience.

The effects of student engagement on student satisfaction are complex (Astin 1999). The aforementioned studies have demonstrated that student engagement relates to student satisfaction in a variety of ways. However, student engagement is a multidimensional construct (Zhoc et al. 2018) and previous research has not differentiated the correlations between the different aspects of student engagement with student satisfaction. Besides, the bulk of the research has mostly looked at cognitive and behavioral engagement along with institutional traits. Research on the impact of emotions or emotional engagement on student satisfaction is rather limited, as scholars argued that ‘we lack studies on positive emotions in education, and in learning and achievement generally’ (Pekrun et al. 2002a, p. 150). It is only much more recently that emotions and emotional engagement are becoming more prominent in educational research.

Emotions impact students’ learning process and outcomes by changing cognitive recourses and strategies, and behaviors (Pekrun et al. 2002b). Ashby et al. (1999) reported that emotions influence the dopamine level and memory of students. Meinhardt and Pekrun (2003) stated that the use of different cognitive recourses is directed by students’ emotions. Goetz et al. (2006) showed the connections between positive emotions and students’ behaviors such as problem-solving and self-regulated learning. Liljander and Bergenwall (2002) argued that emotions rather than cognitive attributes better predict individual’s behavior and behavioral intention. In addition, emotions direct the overall level of student engagement, with positive emotions triggering engagement while buffering against disengagement (King et al. 2015). Given the growing attention to emotions in the learning process, whether emotional engagement influences student satisfaction and how it influences student satisfaction become important questions to be answered.

The interest in student engagement appeared in China at the turn of 21th century when Chinese higher education embraced a developing stage of massification. In China, cognitive engagement (e.g., effortful processing of information) and behavioral engagement (e.g., working hard) are more aligned with the classic notions of learning among Chinese, and have attracted research attention (Guo et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2015). Emotional engagement has usually been under-appreciated in Chinese culture. There is a lack of research on the emotions of Chinese college students. Moreover, research on the impact of emotions or emotional engagement on student satisfaction is rather limited.

Student Satisfaction

Student satisfaction has become an important theme in the sector of higher education over the past two decades given massification and neo-liberal trends towards marketization (García-Aracil 2009; Navarro et al. 2005). Living in a mass higher education system where supply is sufficient or even exceeds demand, institutions can no longer establish education standards just by reference to internal or professionally determined norms. Instead, students’ perception of education quality and experience, conceptualized as student satisfaction, has emerged as a crucial outcome in the higher education field (Giroux 2002; Navarro et al. 2005). In China, student satisfaction has been selected by Ministry of Education (MoE) as one of the five major benchmarks to evaluate the quality and development of Chinese college education since 2016.Footnote 1

In the literature, student satisfaction is a short-term attitude resulting from students’ evaluation of their perceived learning experience at university and it is an important type of college students’ perceived learning outcomes (Elliot and Healy 2001). Previous studies have focused on institutional factors to examine the impact that university and college exert on student satisfaction. Institutional factors that facilitate student satisfaction include (but are not limited to) teachers’ capability to transmit innovative information, communicate with students, deliver teaching content, and provide useful study materials (Ledden et al. 2011; Pedro et al. 2018; Petruzzellis et al. 2006); and the image and prestige of the university (Bennett and Ali-Choudhry 2009; Helgesen and Nesset 2007; Weerasinghe and Dedunu 2017).

Aside from the aforementioned institutional factors, Aldemir and Gülcan (2004) stated that students’ intrapersonal factors also play an important role on their satisfaction. Gender, discipline, and academic achievement are the factors reported to influence student satisfaction (Umbach and Porter 2002; Appleton-Knapp and Krentler 2006; Radloff and Coates 2010; Parahoo et al. 2013), with female students, students registered in faculties that emphasize research, and students with higher levels of academic achievement tending to report higher levels of satisfaction. However, student satisfaction has been mostly studied in relation to institutional factors but not student intrapersonal factors. Besides, the interactive relations between institutional and individual traits along with their impact on student satisfaction have not been explained.

This study aims to examine the impact of emotions on student satisfaction and test whether emotional engagement can amplify the effects of cognitive and behavioral engagement on student satisfaction. This study is methodologically rigorous. It is based on data from the 2012 China College Student Survey (CCSS) which generates a random sample of Chinese college students and by far this is the only dataset with nationwide representativeness.

To be specific, this study has the following key objectives:

-

(1)

Describe the engagement of Chinese college students.

-

(2)

Examine how behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement predicts student satisfaction of Chinese college students.

-

(3)

Examine the moderating effect of emotional engagement between cognitive engagement and student satisfaction, and between behavioral engagement and student satisfaction.

Two hypotheses are proposed in accordance:

H1

Emotional engagement will positively predict student satisfaction.

H2

Cognitive and behavioral engagement will positively predict student satisfaction.

Methods

Participants

The sample was obtained from CCSS 2012, a survey adapted from the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) developed in the United States for the context of Chinese higher education (Luo et al. 2009). CCSS 2012 consists of Chinese college students from 55 sample higher education institutions (N = 67,182; 45.6% female, 54.4% male).

A two-stage stratified sampling strategy was used to guarantee that the samples were representative of the national populations of college students in China. First, sample institutions were selected randomly in proportion by type and geographic area of China. Second, given numbers of samples (400–800) of individual students were randomly selected from each grade in each sample institution. In the end, the survey generated 55 sample institutions, including two C9 universities, eight ‘985 Project but not C9’ universities, fifteen ‘211 Project but not ‘985 Project’ universities,Footnote 2 and thirty local higher education institutions, with an average response rate of 79.7%. We use sampling weights to adjust the oversampling of elite universities.

Variables

Dependent Variable

This study takes student satisfaction as the dependent variable, measured using a 7-point Likert scale (from 1=very bad to 7=very good), asking students to report how they felt about their learning experience as a whole at the universities they attended.

Independent Variables

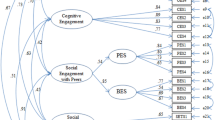

This study adopted the three-dimensional construct of student engagement suggested by Fredricks et al. (2004).

Behavioral Engagement

Behavioral engagement was measured using a 4-point Likert scale (a = 0.73) ranging from 1=totally disagree to 4 = totally agree. Its seven items asked students to report on the frequencies of their behaviors related to course learning at university, including concentrating on listening to lecturers in class, taking notes with emphasis in class, thinking about and answering the questions raised by lecturers, doing presentations in class, working collaboratively with peer students on tasks given by lecturers, going to the library or studying outside of class, and discussing assignments or laboratory work with peer students outside of class.

Cognitive Engagement

Cognitive engagement was measured using a 4-point Likert scale (a = 0.71). Four items were used to ask students to report on the frequencies of using reflective and integrative learning strategies: reflecting and evaluating on your own learning process, challenging your own viewpoints, integrating the perspectives of courses with your own experiences and knowledge, and integrating different sources of information or viewpoints while writing essays or doing projects.

Emotional Engagement

This study measured emotional engagement using a 4-point Likert scale (a = 0.64). Two items were used to ask students to report on whether they liked to study and whether they felt enjoyment while studying.

Covariates

We accounted for potential third variables by including seven control measures in our models. At the student level, we controlled for variables related to the individual’s background, such as gender (male or female), household (urban or rural), and only child status (yes or no). At the institutional level, we controlled for the institutional status variable (‘985 Project’, ‘211 Project but not 985 Project’, and local universities) to determine the prestige and resources of the university. We also controlled for interactive variables in terms of both individual and institutional traits, such as the quality of social relationships (SR) at the university, measured using a four-item scale (a = 0.801) asking students to report on how well they dealt with their peer students, faculty members, staff in charge of student affairs, and administrators of the university based on a 7-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = not good and not helpful at all to 7 = very good and very helpful); students’ interest in their majors, measured using a 4-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = not interested at all to 4 = very interested) with students asked to report on whether they felt interested in their majors; and students’ motivation, measured using a 7-point Likert scale (from 1 = very weak to 7 = very strong) with students asked to report on how well they were motivated to study during the semester.

Statistical Analysis

To examine how behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement predicts Chinese college students’ satisfaction, we conduct multivariate regression analysis. The multivariate regression equations take the form of

To test the moderating effect of emotional engagement on the relationship between students’ cognitive engagement and satisfaction and between behavioral engagement and student satisfaction, we adopt moderated multiple regression technique recommended by Villa et al. (2003).

To test whether a variable Z moderates the relationship between a predictor X and a criterion variable Y, we add an interaction term, which is the product of the predictor X and the moderator Z, into the main effects model. The moderated multiple regression equation takes the form of

If the interaction term (\(\beta _{3}\)) is significant, the moderating effects of Z are indicated.

Results

Student Satisfaction of Chinese College Students

Data from 2012 CCSS indicated that 56.67% of Chinese college students felt satisfied with their total learning experience at university, with students of prestigious universities (‘985 Project’) reporting slightly higher satisfaction (66.39%) and those at ‘211 Project’ and local universities reporting lower-than-average satisfaction levels (56.64% and 53.61%, respectively). Female college students (59.87%) were more satisfied with their learning experience at university than male college students (53.98%). College students who came from rural areas (55.1%) were not as satisfied as their peer groups who came from urban areas (58.04%) (Fig. 1).

Student Engagement of Chinese College Students

69.49% of Chinese college students reported they felt emotionally engaged while they studied. Female college students (73.99%) and students from rural areas (72.24%) reported higher levels of emotional engagement during studying than male students (65.73%) and urban students (66.95%), and students from prestigious universities (‘985 Project’) reported higher levels of emotional engagement during studying (71.35%) than students from ‘211 Project’ universities (69.69%) and local universities (68.79%) (Fig. 2).

By comparison, Chinese college students reported lower levels of behavioral and cognitive engagement, with an average score around 12 points lower. It seems Chinese college students have higher levels of emotional rather than cognitive and behavioral engagement (Fig. 3).

Behavioral, Cognitive, and Emotional Engagement Predict Student Satisfaction of Chinese College Students

The unstandardized means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations of the main variables are reported in Table 1. The correlations are in the expected direction. As Table 1 shows, there is a statistically significant positive relationship between students’ satisfaction with their total experience at university based on their behavioral engagement (r = 0.29), cognitive engagement (r = 0.22), emotional engagement (r = 0.23), social relationship (r = 0.48), students’ interests in their majors (r = 0.32), learning motivation (r = 0.36), and overall engagement (r = 0.32). This shows that students who are more motivated, are more interested in their majors, have higher levels of behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement, and have better social relationships at university tend to be more satisfied with their overall experience at university, with social relationships being the most influential factor.

To examine whether behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement predict Chinese college students’ satisfaction, we constructed a regression model with student satisfaction as the outcome variable and with gender, household, only child status, type of institution, social relationships, interest in major, motivation, behavioral engagement, cognitive engagement, and emotional engagement as predictors. As Table 2 shows, all of the variables effectively predict the level of student satisfaction, except for only child status. Specifically, students who are female (b = 0.03, t = 3.73, p < 0.001); are from urban households (b = 0.02, t = 3.16, p < 0.01); attend higher-status institutions (b = 0.12, t = 28.66, p < 0.001); have better social relationships at university (b = 0.04, t = 9.61, p < 0.001); are more motivated to learn (b = 0.04, t = 9.74, p < 0.001); are more interested in their majors (b = 0.01, t = 3.24, p < 0.001); and have higher levels of behavioral engagement (b = 0.36, t = 101.25, p < 0.001), cognitive engagement (b = 0.17, t = 48.96, p < 0.001), and emotional engagement (b = 0.15, t = 38.79, p < 0.001) in learning tend to be more satisfied with their overall experience at university.

The Moderating Effect of Emotional Engagement

We test the moderating effect of emotional engagement between behavioral and cognitive engagement with student satisfaction. We constructed a regression model with emotional engagement interacting with behavioral engagement and cognitive engagement after centering the variables. As Table 3 shows, all of the variables effectively predict the level of student satisfaction, and emotional engagement moderates the association between cognitive engagement and student satisfaction (b = ‒ 0.01, t = ‒ 3.60, p < 0.001), while such a moderating effect does not exist between behavioral engagement and student satisfaction.

As indicated in Fig. 4, for students with low cognitive engagement, positive emotional engagement amplified their satisfaction with the overall experience at university; for students with high cognitive engagement, negative emotional engagement weakened their school satisfaction; and when students’ level of cognitive engagement increases to a certain degree, the influence of emotional engagement on their satisfaction tends to disappear. Emotional engagement plays a moderating role in the relationship between cognitive engagement and student satisfaction.

Conclusion, Educational Implications, and Limitations

Based on data from a cross-national survey following the strategy of stratified sampling, we consider Chinese college students’ emotional engagement in this study. In contrast with the stereotypical impression that Chinese students are passive learners, our study finds that Chinese college students are a group of positive learners who enjoy studying; on average, 69.49% of the students reported feeling emotionally engaged while studying. Nevertheless, only slightly over half of the students (56.67%) felt satisfied with their overall learning experience at university, with 31.30% feeling rather satisfied, 18.14% feeling satisfied, and 7.23% feeling very satisfied.

China has one of the highest urban–rural income ratios in the world, and the learning process and outcomes of college students are influenced by various socioeconomic factors that are embedded in their own backgrounds (Sicular et al. 2007). Interestingly, students from disadvantaged social groups (female, rural background) reported higher levels of emotional engagement. Simultaneously, students from prestigious universities reported higher levels of emotional engagement. A similar trend existed for student satisfaction, except that rural students felt less satisfied with their overall learning experience at university than their urban parallels. This could be partially attributed to the cultural alienation that rural college students experience when they migrate to the universities that are rooted in an urban culture, sometimes even a cosmopolitan one, although such migration is desirable. (Huang and Zhang 2008).

We also examine how behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement predict student satisfaction of Chinese college students. All three aspects of student engagement predict the level of student satisfaction at a level of statistical significance. Furthermore, this study empirically tests the moderator effect of emotional engagement on the relationship between behavioral and cognitive engagement and student satisfaction. We find that the moderating effect of emotional engagement on the relationship between cognitive engagement and student satisfaction exists, while our hypothesis on the moderating effect on the relationship between behavioral engagement and student satisfaction is rejected. That is to say, for students with low cognitive engagement, positive emotional engagement can improve their satisfaction with their overall experience at university; for students with high cognitive engagement, low emotional engagement can reduce their school satisfaction. This finding has important implications for the management and policies of higher education in China.

This study helps to establish legitimacy for adopting the conception of ‘enjoyable learning’ in Chinese higher education. It shows that when students emotionally engage in more study behavior at university, they tend to be more satisfied with their learning experiences, which may indicate a turn in educational value and culture in China. Cortazzi (1990) stated that there were basically two conceptions of teaching and learning. One is hierarchical, positioning the teacher as all-knowing and his or her knowledge as something that is transmitted directly to learners. The other is more egalitarian, considering learners as individuals who creatively build up knowledge through activity, participation, and independent thinking. The first conception has often been associated with the stress Chinese or Asian culture places on ‘continuity, stability, and group identity’ (Cortazzi 1990, p. 58), while the second is linked to Western cultures that emphasize individual development, innovation, and an egalitarian ambiance. As the Chinese education system becomes more democratic, the educators and administrators at higher education institutions begin demanding more positive engagement for students. As reformers have subjected Chinese higher education to marketization and massification, student power has risen in the form of customer power. The empowerment of Chinese college students helps to free them from authoritarian relationships with faculty members and universities per se. How to promote students’ positive emotions during their studies at university has become an important issue on the agenda of reformers.

A key implication that can be drawn from this study is that if we take student satisfaction as one form of educational success for both institutions and individual students, promoting students’ emotional engagement is a way to achieve that success. This again reminds educators of the critical role of learners’ emotions in promoting instruction.

The present study has certain limitations. First, self-reports are the sole source of data and information. Although self-reports provide important insights into how students perceive and interpret situations (Op’t Eynde and Turner 2006), they present two main risks: (a) socially desirable responses and (b) lack of insight into their own thoughts, emotions, behaviors, and other psychological states (Else-Quest et al. 2008). Second, student satisfaction is the only indicator related to college students’ perceived learning outcome in this study. We plan to further explore the role of emotional engagement on other crucial indicators of learning outcomes such as academic achievement.

Notes

The other four benchmarks are social demand adaptation, college-running conditions, fulfillment of education goals, and effectiveness of quality assurance (MoE 2016).

The Chinese central government inaugurated ‘211 Project’ in 1995 which ascribed 116 universities to first tier of the national higher education system. These universities are provincial flagship universities that promote both national and regional economic development. ‘985 Project’ was implemented in 1998 and 39 universities were selected from the list of ‘211 Project’ as national flagship universities to pursue world-class status. In 2009, the C9 League was established by 9 elite universities of ‘985 Project’ following the pattern of Ivy League in the United States and the Russell Group in the UK. These universities are committed to serving the national goal to compete in global knowledge society.

References

Abrahamowicz, D. (1988). College involvement, perceptions, and satisfaction: A study of membership in student organizations. Journal of College Student Development, 29(3), 233–238.

Aldemir, C., & Gülcan, Y. (2004). Student satisfaction in higher education: A Turkish case. Higher Education Management and Policy, 16(2), 109–122.

Appleton-Knapp, S., & Krentler, K. (2006). Measuring student expectations and their effects on satisfaction: The importance of managing student expectations. Journal of Marketing Education, 28(3), 254–264.

Ashby, F., Isen, A., Turken, U., & Bjork, R. A. (1999). A neuropsychological theory of positive affect and its influence on cognition. Psychological Review, 106(3), 529–550.

Astin, A. W. (1984). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of College Student Personnel, 25, 297–308.

Astin, A. W. (1985). Achieving educational excellence: A critical assessment of priorities and practices in higher education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Astin, A. W. (1991). Assessment for excellence: The philosophy and practice of assessment and evaluation in higher education. New York: American Council on Education.

Astin, A. W. (1999). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of College Student Development, 40(5), 518–529.

Bennett, R., & Ali-Choudhury, R. (2009). Prospective students’ perceptions of university brands: An empirical study. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 19(1), 85–107.

Berger, J. B., & Milem, J. F. (1999). The role of student involvement and perceptions of integration in a causal model of student persistence. Research in Higher Education, 40(6), 641–664.

Carini, R. M., Kuh, G. D., & Klein, S. P. (2006). Student engagement and student learning: Testing the linkages. Research in Higher Education, 47(1), 1–32.

Coates, H. (2006). Student engagement: The specification and measurement of student engagement. A Symposium on Student engagement measuring and enhancing engagement with learning Frederic Wallis House Conference Centre, Lower Hutt, New Zealand, New Zealand Universities Academic Audit Unit.

Cortazzi, M. (1990). Cultural and educational expectation in the language classroom. In B. Harrison (Ed.), Cultural and language classroom (pp. 54–65). Hong Kong: Modern English Publications and the British Council.

Dai, Y., & Sternberg, R. J. (2004). Motivation, emotion, and cognition: Integrative perspectives on intellectual functioning and development. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Damasio, A. (2003). Feelings of emotion and the self. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1001, 253–261.

Elliott, K. M., & Healy, M. A. (2001). Key factors influencing student satisfaction related to recruitment and retention. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 10(4), 1–11.

Else-Quest, N. M., Hyde, J. S., & Hejmadi, A. (2008). Mother and child emotions during mathematics homework. Mathematical Thinking and Learning, 10, 5–35.

Ertl, H., & Wright, S. (2008). Reviewing the literature on the student learning experience in higher education. London Review of Education, 6(3), 195–210.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74, 59–109.

García-Aracil, A. (2009). European graduates’ level of satisfaction with higher education. Higher Education, 57(1), 1–21.

Giroux, H. A. (2002). Neoliberalism, corporate culture, and the promise of higher education: The university as a democratic public sphere. Harvard Educational Review, 72(4), 425–463.

Goetz, T., Hall, N. C., Frenzel, A. C., & Pekrun, R. (2006). A hierarchical conceptualization of enjoyment in students. Learning and Instruction, 16(4), 323–338.

Guo, F., Yao, M., Zong, X., & Yan, W. (2016). The developmental characteristics of engagement in service-learning for Chinese college students. Journal of College Student Development, 57(4), 447–459.

Helgesen, O., & Nesset, E. (2007). Images, satisfaction and antecedents: Drivers of student loyalty? A case study of a Norwegian university college. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(1), 38–59.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Langer, M. F., & Hansen, U. (2001). Modeling and managing student loyalty. Journal of Service Research, 3(4), 331–344.

Huang, H., & Zhang, D. (2008). Nongcunji daxuesheng de chengshi shiying yanjiu: Yixiang laizi jiangsu beibu nongcunji daxuesheng de diaocha [A study on the adaptation of rural student to urban life: based on the survey of the rural college students who come from the northern part of Jiangsu province]. Fujian Tribune, 4, 103–106.

Jimerson, S. J., Campos, E., & Grief, J. L. (2003). Toward an understanding of definitions and measures of school engagement and related terms. The California School Psychologist, 8, 7–27.

King, R. B., Mcinerney, D. M., Ganotice, F. A., & Villarosa, J. B. (2015). Positive affect catalyzes academic engagement: Cross-sectional, longitudinal, and experimental evidence. Learning and Individual Differences, 39, 64–72.

Kotze, T. G., & du Plessis, P. J. (2003). Students as ‘co-producers’ of education: A proposed model of student socialisation and participation at tertiary institutions. Quality Assurance in Education, 11(4), 186–201.

Kuh, G. D., Schuh, J. H., Andreas, R. E., Lyons, J. W., & Strange, C. C. (1991). Involving colleges. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kuh, G. D. (2001). Assessing what really matters to student learning: Inside the National Survey of student engagement. Change, 33, 10–17.

Kuh, G. D. (2006). Making students matter. In J. C. Burke (Ed.), Fixing the fragmented university: Decentralization with discretion (pp. 235–264). Boston: Jossey-Bass.

Ledden, L., Kalafatis, S. P., & Mathioudakis, A. (2011). The idiosyncratic behaviour of service quality, value, satisfaction, and intention to recommend in higher education: An empirical examination. Journal of Marketing Management, 27(11–12), 1232–1260.

Liljander, V., & Bergenwall, M. (2002). Consumption-based emotional responses related to satisfaction. Occasional Paper, Swedish School of Economics and Business Administration, Department of Marketing.

Luo, Y., Ross, H., & Cen, Y. (2009). Higher education measurement in the context of globalization: The cultural adaptation, reliability and validity of NSSE-China. Fudan Education Forum, 7(5), 12–18.

Meinhardt, J., & Pekrun, R. (2003). Attentional resource allocation to emotional events: An ERP study. Cognition and Emotion, 17(3), 477–500.

Meyer, D. K., & Turner, J. C. (2002). Discovering emotion in classroom motivation research. Eucational Psychologist, 37(2), 107–114.

MoE. (2016). A series of quality reports on Chinese higher education. Retrieved from https://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/xw_fbh/moe_2069/xwfbh_2016n/xwfb_160407/160407_sfcl/201604/t20160406_236891.html.

Navarro, M. M., Iglesias, M. P., & Torres, P. R. (2005). A new management element for universities: Satisfaction with the offered courses. International Journal of Educational Management, 19(6), 505–526.

Opteynde, P., & Turner, J. (2006). Focusing on the complexity of emotion issues in academic learning: A dynamical component systems approach. Educational Psychology Review, 18, 361–376.

Panksepp, J. (2003). At the interface of the affective, behavioral, and cognitive neurosciences: Decoding the emotional feelings of the brain. Brain and Cognition, 52(1), 4–14.

Parahoo, S. K., Harvey, H. L., & Tamim, R. M. (2013). Factors influencing student satisfaction in universities in the Gulf region: Does gender of students matter? Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 23(2), 135–154.

Pedro, E., Mendes, L., & Lourenço, L. (2018). Perceived service quality and students satisfaction in higher education. International Journal for Quality Research, 12(1), 165–192.

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. (2002). Positive emotions in education. In E. Frydenberg (Ed.), Beyond coping: Meeting goals, visions, and challenges (pp. 149–173). Oxford: Oxford Universtiy Press.

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. (2002b). Academic emotions in students' self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 91–105.

Petruzzellis, L., D’Uggento, A. M., & Romanazzi, S. (2006). Student satisfaction and quality of service in Italian universities. Managing Service Quality, 16, 349–364.

Radloff, A., & Coates, H. (2010). Doing more for learning: Enhancing engagement and outcomes. Australasian Survey of Student Engagement: Australasian Student Engagement Report. Camberwell: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Sicular, T., Yue, X., Björn, G., & Li, S. (2007). The urban-rural income gap and inequality in China. Review of Income and Wealth, 53(1), 93–126.

Umbach, P. D., & Porter, S. R. (2004). How do academic departments impact student satisfaction? Understanding the contextual effects of departments. Research in Higher Education, 43(2), 209–234.

Villa, J. R., Howell, J. P., Dorfman, P. W., & Daniel, D. L. (2003). Problems with detecting moderators inleadership research using moderated multiple regression. Leadership Quarterly, 14(1), 3–23.

Weerasinghe, I., & Dedunu, H. (2017). University staff, image and students’ satisfaction in selected state universities. Journal of Business and Management, 19(5), 34–37.

Zhang, Z. H., Wen, H., & McNamara, O. (2015). Undergraduate student engagement at a Chinese university: A case study. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 27(2), 105–127.

Zhoc, K. C., King, R. B., Webster, B. J., Li, J. S., & Chung, T. (2018). Higher education student engagement scale: Development and psychometric evidence. Research in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9510-6.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, Y., Xie, M. & Lian, Z. Emotional Engagement and Student Satisfaction: A Study of Chinese College Students Based on a Nationally Representative Sample. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 28, 283–292 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-019-00437-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-019-00437-5