Abstract

Previous literature emphasized the role of psychological capital (PsyCap) in fostering positive organizational and work outcomes. However, there were very scarce investigations on the benefits of PsyCap especially in non-Western academic settings. The current research addresses this gap through assessing the extent to which PsyCap can be associated with optimal academic and well-being outcomes. There were 606 Filipino high school students who were recruited in the study. The results of structural equation modeling revealed that PsyCap positively predicted academic engagement, flourishing, interdependent happiness, and positive affect. Implications of the findings are elaborated in terms of how PsyCap can potentially assist in facilitating positive student outcomes in a non-Western context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With the complex array of academic demands in various educational institutions, optimizing academic success in students remains to be a challenging task for principals, teachers, counselors, and school psychologists. Consequently, some research programs focused on assessing the role of positive psychological constructs in facilitating relevant student outcomes such as academic engagement and happiness. Drawing from the positive organizational behavior paradigm (Luthans 2002a, b) which delves with “the study and application of positively oriented human resource strengths and psychological capacities that can be measured, developed, and effectively managed for performance improvement” (Luthans 2002b, p. 59), recent studies explored the beneficial impact of psychological capital (PsyCap) in facilitating positive student outcomes (i.e., Li et al. 2014; Siu et al. 2014).

PsyCap is a state-like positive motivational condition that arises from one’s endorsement of hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy (Luthans and Youssef 2004). Luthans et al. (2007a, b) defined PsyCap as “positive appraisal of circumstances and probability for success based on motivated effort and perseverance” (p. 550). Previous studies have shown that PsyCap positively predicted employee outcomes including work engagement (Avey et al. 2008; Simons and Buitendach 2013), work performance (Luthans et al. 2008), job satisfaction (Luthans et al. 2007a, b, 2008), and organizational citizenship behavior (Beal et al. 2013).

As noted earlier, there are four positive psychological traits that constitute PsyCap. Hope pertains to a thinking orientation which involves eagerness to accomplish desired goals (agency) and availability of strategies to fulfill specific aspirations (Snyder et al. 1991). Optimism, on the other hand, refers to expectations that good and positive things will take place in the future (Scheier and Carver 1985). Scheier et al. (2001) asserted that optimists are likely to use more adaptive forms of coping (approach coping) than maladaptive ones (avoidant coping). Resilience refers to individual’s capability to effectively adapt when facing notable adversity and negative circumstances (Masten and Reed 2002). One more important dimension of PsyCap is self-efficacy. Bandura (1997) contended that self-efficacy pertains to an individual’s perceived capacity to accomplish specific behaviors. Given that PsyCap’s dimensions seemed to be adaptive in nature, previous investigations looked at the relative influence of PsyCap on wide range of positive outcomes.

Past literature showed that PsyCap was associated with desirable psychological outcomes in various organizations. PsyCap was positively correlated with job satisfaction (Luthans et al. 2007a, b, 2008), organizational citizenship behavior (Beal et al. 2013), organizational commitment (Luthans et al. 2007a, b, 2008), positive affect (Murray et al. 2010), well-being (Avey et al. 2011, 2010; Culbertson et al. 2010), and work engagement (Avey et al. 2008; Simons and Buitendach 2013).

Despite the potential benefits of PsyCap in the organizational setting, little is known about the valuable effects of PsyCap on positive educational outcomes especially in non-Western academic contexts. Among the exceptions were the studies of Siu et al. (2014) and Li et al. (2014) which assessed the psychological benefits of PsyCap in Hong Kong and Chinese student populations. Given that the Philippines is considered a collectivist society (Ching et al. 2014; Datu 2014), the results of this study could provide some evidence on the adaptive role of PsyCap even in collectivist academic contexts. Findings of the present research can also offer notable insights regarding the applicability of Western-derived positive psychological constructs like PsyCap in non-Western sociocultural societies.

Investigating the potential value of PsyCap in optimizing positive psychological outcomes in the Philippines would contribute to the extant literature on the desirable consequences of PsyCap especially in the academic context. While PsyCap was originally intended for employees in the workplace (i.e., Luthans 2002a, b), there are sensible reasons to argue that PsyCap may also be relevant for students. First, like the employees’ workplace, school can be considered as an essential organization that can shape students’ work or occupational-related behaviors. Second, the nature and quality of tasks that a student typically accomplishes (e.g., completing homework, attending class lectures, and reading assigned references) may be regarded as work (Salanova et al. 2010; Siu et al. 2014). Clearly, exploring the relations of PsyCap with optimal outcomes in students could potentially expand the literature on positive education (Seligman et al. 2009) which emphasized the significance of positive psychological states and traits (i.e., PsyCap) to facilitate adaptive learning outcomes (e.g., academic engagement).

Therefore, the central aim of the present research was to assess the beneficial role of PsyCap among Filipino high school students. Specifically, we investigated the relations of PsyCap with relevant student outcomes such as academic engagement, flourishing, interdependent happiness, and positive affect through structural equation modelling.

Psychological Capital and Academic Outcomes

Few investigations highlighted the psychological benefits of PsyCap in the academic context. For instance, Siu et al. (2014) found that PsyCap positively predicted study engagement (which refers to student’s sense of absorption, vigor, and dedication in the class) among Hong Kong Chinese undergraduate students. Further, intrinsic motivation partially mediated the relations between PsyCap and study engagement. PsyCap was also positively linked to academic performance in American undergraduate business students (Luthans et al. 2012).

Psychological Capital and Well-Being

Past literature revealed that PsyCap may be linked to well-being outcomes. Supporting this contention, PsyCap was positively predicted positive affect (Murray et al. 2010), well-being (Avey et al. 2011, 2010; Culbertson et al. 2010). However, these findings were largely based on studies that involved non-student samples in Western settings. To the best of our knowledge, only two studies (Li et al. 2014; Riolli et al. 2012) examined the role of PsyCap on well-being. Li et al. (2014) found that PsyCap mediated the relations between social support and subjective well-being in Chinese undergraduate students. Moreover, Riolli et al. (2012) found that PsyCap was positively correlated with life satisfaction among undergraduate students in an American university.

The Present Study

The chief objective of the present study was to examine the extent to which PsyCap predicts academic and well-being outcomes in the Philippine setting. This hopes to address dearth of empirical investigations on the role of PsyCap especially in non-Western academic contexts. Particularly, we assessed the association of PsyCap with academic engagement, flourishing, interdependent happiness, and positive affect in Filipino high school students through structural equation modelling approach. We examined the potential relationship of PsyCap with academic engagement since Siu et al. (2014) found that PsyCap positively predicted study engagement. Yet, our study was not identical in that we operationalized academic engagement as the extent to which students actively participate on and feel good about classroom activities (Skinner et al. 2009). Unlike the model of Siu et al.’s (2014) which conceptualized engagement as the students’ feeling of absorption, dedication, and enthusiasm towards the class, the present study looked at academic engagement as the degree to which students embody energetic participation in various academic tasks (behavioral engagement) and the intensity of students’ positive feelings when performing classroom activities (emotional engagement).

We also investigated the link of PsyCap to well-being outcomes among high school students because past literature revealed that PsyCap was positively associated with well-being indices in non-student populations (e.g., Avey et al. 2011, 2010; Culbertson et al. 2010). However, our research was unique in that we examined the relationship of PsyCap with wider range of well-being outcomes (i.e., flourishing, interdependent happiness, and positive affect) in a collectivist context. Flourishing pertains to “social-psychological prosperity” which is characterized by purpose in life, satisfying interpersonal relationships, optimism, and engagement (Diener et al. 2010). Interdependent happiness refers to the extent to which individuals experience happiness due to meaningful social interactions (relationship harmony), meeting expected norms in a sociocultural setting (quiescence), and having relatively similar level of achievement with others (ordinariness). Positive affect refers to the extent to which individuals experience positive emotions (MacKinnon et al. 1999).

Hypotheses

H1

PsyCap will positively predict academic engagement.

H2

PsyCap will positively predict flourishing, interdependent happiness, and positive affect.

Methods

Participants

There were six hundred and six Filipino high school students (n = 606) in a private school in Metro Manila who participated in the present empirical investigation. The mean age of the sample is 13.87 with a standard deviation of 1.26. There were 305 female and 300 male participants while 1 failed to report gender. The participants were consented prior to the actual survey administration.

Instruments

Academic Engagement

The Academic Engagement Scale (Skinner et al. 2009) is a 20-item questionnaire that measures the extent to which students are motivated to participate and feel good about their classroom activities. In the present research, only the 10 items that are subsumed in the academic engagement dimension (behavioral engagement and emotional engagement) were used. All items were marked on a 4-point likert scale (1 = not at all true; 4 = very true). Sample items in the said scale involved; “I try to do well in school” (behavioral engagement); “When I’m in class, I feel good” (emotional engagement). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of the academic engagement scale was .80.

Flourishing

The Flourishing Scale (Diener et al. 2010) is an 8-item questionnaire that gauged holistic well-being which involved satisfying interpersonal relationship (My social relationships are supportive and rewarding), purpose in life (I lead a purposeful and meaningful life), optimism (I am optimistic about my future). All items were rated on a 7-point likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of the scale in the present study was .84.

Interdependent Happiness

The Interdependent Happiness Scale (Hitokoto and Uchida 2015) is a 9-item questionnaire that measured the relationally oriented happiness that is quite prominent in collectivist settings. Sample item in the scale includes the following; “I make significant others happy”. All items were marked on 5-point likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of the scale in the current study was .90.

Positive Affect

The 10-item version of the Positive and Negative Affect Scale was used in the current study. Only the items referring to positive emotions (e.g., inspired and excited) were utilized. These items were rated on a 7-point likert scale (1 = very slightly or not at all; 7 = extremely). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of the said scale in the present research was .72.

Psychological Capital

The 16-item modified version of the Psychological Capital Scale (Luthans et al. 2007a, b) was used in the current research to measure the extent to which students’ sense of motivational orientation that is characterized by greater hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy. These were the sample items in modified PsyCap scale; “I am optimistic about my future in school” (optimism); “I feel confident that I can learn what is taught in school” (self-efficacy); “At this time, I am meeting the goals that I have set for myself in school” (hope); and I don’t let stress affect me too much (resilience). The dimensions of the PsyCap scale had the following Cronbach’s alpha coefficients; hope (α = .70); optimism (α = .60); resilience (α = .70); and self-efficacy (α = .60). The overall Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of the PsyCap scale in the present research was .83.

The English versions of the said questionnaires were used in the present study because previous literature revealed that the English forms of psychological scales were also applicable for Filipino students (e.g., Ganotice et al. 2012; King and Watkins 2012).

Data Analysis

Measures of descriptive statistics like mean, standard deviation, and critical ratio of skewness were computed. Note that there were no missing responses in the current research. Then, we followed the two-step approach of Anderson and Gerbing (1988) to test our hypothesized structural equation model (SEM). Jöreskog and Sörbom (2003) asserted that this approach is necessary in that meaningful inferences about the hypothesized SEM can only be achieved when measurement model is considered valid (the indicators significantly load on the latent constructs). The first step involved assessing a measurement model wherein all variables served as latent constructs with its parcels as indicators through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Testing a measurement model that involved all the variables in the current study (i.e., PsyCap, academic engagement, flourishing, interdependent happiness, and positive affect) ensured that such variables are well represented by their respective indicators. It also aimed to assess whether or not each construct was distinct from each other. Prior to carrying out CFA among all the variables in AMOS 18.0 software, we created 4 item parcels for PsyCap, 2 item parcels for academic engagement, 3 parcels for flourishing, 3 parcels for interdependent happiness, and 3 parcels for positive affect to prevent the possibility of inflated measurement errors that may be caused by multiple items in such latent constructs (Little et al. 2002). The second step involved testing the proposed SEM through maximum likelihood estimation where PsyCap served as the antecedent variable of academic engagement, flourishing, interdependent happiness, and positive affect. Several fit indices were reviewed to check the validity of the said measurement model in the present sample. The recommendations of Hu and Bentler (1999) were followed in examining the validity of path model namely; (a) non-significant Chi square test statistic; (b) goodness of fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and Normed Fit Index (NFI) values should be greater than .90; and (c) Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value should be less than .08.

Results

Measurement Model

The hypothesized measurement model involved five latent variables (i.e., PsyCap, academic engagement, flourishing, interdependent happiness, and positive affect) and 15 manifest variables. The results of CFA revealed a good-fitting model: χ 2 = 203.97; df = 80; p = .000, χ 2 /df = 2.55; CFI = .96; GFI = .96; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .05. All the observed variables subsumed in each latent construct had significant factor loadings (p < .001) which suggests that all the latent variables were best characterized by the aforementioned indicators. Table 1 showed the descriptive statistics and correlational coefficients among the variables. As expected, PsyCap was positively correlated with academic engagement, flourishing, interdependent happiness, and positive affect.

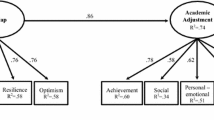

Structural Model

As we found that the proposed measurement model significantly fits the present sample, we tested a structural equation model with PsyCap as the antecedent variable and academic engagement, flourishing, interdependent happiness, and positive affect as outcome variables. The model had very good fit indices: χ 2 = 293.14; df = 86; p = .000, χ 2 /df = 3.41; CFI = .94; GFI = .94; TLI = .93; RMSEA = .06 (See Fig. 1). Consistent with our hypotheses, the path from PsyCap to academic engagement was significant (β = 80, p < .001). PsyCap also positively predicted flourishing (β = 76, p < .001), interdependent happiness (β = 54, p < .001), and positive affect (β = 73, p < .001). These results suggest that PsyCap may be positively associated with academic and well-being outcomes.

Discussion

The main objective of the current study was to examine the relationship of PsyCap with academic and well-being outcomes in Filipino high school students. The findings were generally consistent with the extant literature on the beneficial role of PsyCap on engagement and well-being indices even in non-Western academic settings.

The results showed full support on the first hypothesis (H1) as the path from PsyCap to academic engagement was significant. This suggests that students who espouse combination of hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy may actively partake in various classroom tasks (behavioral engagement) and feel good in doing academic activities (emotional engagement). This was consistent with previous studies regarding the adaptive role of PsyCap on academic engagement (Siu et al. 2014) and work engagement (Avey et al. 2008; Simons and Buitendach 2013). However, one notable difference of our present research from past literature is that we concentrated on assessing the role of PsyCap in optimizing positive outcomes in the educational context among high school students while previous studies examined the role of PsyCap in undergraduate students. Our research was also distinct from that of Siu et al.’s (2014) because we utilized the student engagement model of Skinner et al. (2009) which posits that academic engagement involved the degree to which students energetically work on academic tasks and feel good about accomplishing such tasks unlike Siu’s investigation which operationalized study engagement as the extent to which students endorse absorption, dedication, and vigor when participating in academic activities.

The results were also consistent with H2 on the positive association between PsyCap and well-being outcomes since PsyCap was positively associated with flourishing, interdependent happiness, and positive affect. These results imply that endorsement of multiple psychological resources in the form of hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy may be linked to greater cognitive, affective, psychological, and social well-being. These findings corroborated with the extant literature on the beneficial role of PsyCap on well-being indices (Avey et al. 2011, 2010; Culbertson et al. 2010; Li et al. 2014; Riolli et al. 2012). However, our research addressed important gaps on the relations of PsyCap with wide range of well-being outcomes in student populations.

There are theoretically sensible reasons as to why it is possible that PsyCap may be related to optimal student outcomes (e.g., academic engagement, flourishing, and positive affect). First, Luthans et al. (2007a, b) proposed that positive organizational behavior constructs like psychological capital functions as a positive motivational orientation that would enable individuals to achieve a successful and satisfying life. This is because individuals who have durable psychological resources like PsyCap are likely to experience greater positive emotions (Murray et al. 2010), life satisfaction (Riolli et al. 2012), work engagement (i.e., Avey et al. 2008; Simons and Buitendach 2013), academic achievement (Luthans et al. 2012), and academic engagement (Siu et al. 2014). Second, the conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll 2002) postulates that possessing multiple psychological resources (as in the case of PsyCap) would empower individuals to vigorously work on specific occupational goals and to achieve well-being despite the ever-present challenges and demands in life. Given these theoretical assumptions, it appears that students would reap the psychological benefits of espousing PsyCap on relevant school outcomes because it could potentially enhance their ability to express positive reactions and dynamically take part in classroom or learning activities.

Taken together, the findings of the current empirical investigation revealed interesting insights on the adaptive role of PsyCap in the academic setting. Before elucidating the contributions of the study to existing psychological theory and practices, some limitations should be considered. First, the present research utilized a cross-sectional design which may raise potential issues regarding the validity of the results. It is recommended for future studies to employ longitudinal designs to strengthen the claim regarding the association between PsyCap and optimal educational outcomes. Second, the present study only selected Filipino samples. Hence, future researches are encouraged to examine the beneficial impact of psychological capital among secondary students in other potentially collectivist settings. Third, since the present research relied on self-report data to examine the psychological benefits of PsyCap, future empirical investigations are recommended to use other data collection strategies such as peer-report and teacher-report ratings.

Even with certain limitations, the current study had important theoretical contributions. Consistent with the psychological capital theory, the results offered evidence on the positive role of PsyCap in the academic context given that past literature concentrated on the extent to which PsyCap leads to desirable psychological outcomes among undergraduate student samples in Western contexts (i.e., Luthans et al. 2012; Riolli et al. 2012) and non-Western settings like Hong Kong (Siu et al. 2014) and China (Li et al. 2014). Furthermore, while previous studies have consistently shown that PsyCap leads to positive well-being and work-related outcomes (e.g., Culbertson et al. 2010; Li et al. 2014; Riolli et al. 2012), the present research expanded this line of research area through assessing the relations of PsyCap with various subjective measures of success in Filipino high school students. Also, through examining the association of PsyCap with flourishing, interdependent happiness, and positive affect, the current study extended the nomological network of PsyCap in a collectivist context.

The results of the study had some practical contributions. For instance, school administrators, teachers, school psychologists, and counselors in non-Western contextual settings are encouraged to collaboratively work on conceptualizing, planning, and carrying out educational and counseling psychological programs that aim nurture students’ durable psychological resources like psychological capital to facilitate positive psychological functioning in academic contexts. An essential component of the program should involve longitudinal assessment on the positive impact of PsyCap on student success. Implementation of PsyCap-oriented programs could not only optimize greater academic engagement and well-being but would also prevent occurrence of maladaptive outcomes (e.g., dropout, absenteeism, and depression). In general, our empirical investigation expanded the literature on the positive education paradigm (Seligman et al. 2009) through showing that positive psychological constructs like PsyCap may be linked to optimal learning (e.g., academic engagement) and well-being outcomes in a non-Western academic context.

References

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423.

Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., Smith, R. M., & Palmer, N. (2010). Impact of positive psychological capital on employee well-being over time. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(1), 17–28.

Avey, J. B., Reichard, R., Luthans, F., & Mhatre, K. H. (2011). Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 22, 127–151.

Avey, J., Wernsing, T., & Luthans, F. (2008). Can positive employees help positive organizational change? Impact of psychological capital and emotions on relevant attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 44, 48–70.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Beal III, L., Stavros, J.M., & Cole, M.L. (2013). Effect of psychological capital and resistance to change on organisational citizenship behaviour. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology/SA Tydskrif vir Bedryfsielkunde, 39(2), 1–11.

Ching, C. M., Church, A. T., Katigbak, M. S., Reyes, J. A. S., Tanaka-Matsumi, J., Takaoka, S., et al. (2014). The manifestation of traits in everyday behavior and affect: A five-culture study. Journal of Research in Personality, 48, 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2013.10.002.

Culbertson, S. S., Fullagar, C. J., & Mills, M. J. (2010). Feeling good and doing great: The relationship between psychological capital and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15, 421–433.

Datu, J. A. D. (2014). Validating the revised self-construal scale in the Philippines. Current Psychology,. doi:10.1007/s12144-014-9275-9.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D. W., Oishi, S., et al. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97, 143–156. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y.

Ganotice, F. A., Bernardo, A. B. I., & King, R. B. (2012). Testing the factorial invariance of the English and Filipino versions of the Inventory of School Motivation with bilingual students in the Philippines. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 30(3), 298–303.

Hitokoto, H., & Uchida, Y. (2015). Interdependent happiness: Theoretical importance and measurement validity. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16, 211–239.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6, 307–324.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

King, R. B., & Watkins, D. A. (2012). Cross-cultural validation of the five-factor structure of social goals. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 30(2), 181–193.

Li, B., Ma, H., Guo, Y., Xu, F., Yu, F., & Zhou, Z. (2014). Positive psychological capital: A new approach to social support and subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality, 42(1), 135–144.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 151–173.

Luthans, F. (2002a). The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 695–706.

Luthans, F. (2002b). Positive organizational behavior: Developing and managing psychological strengths. Academy of Management Executive, 16, 57–72.

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007a). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60, 541–572.

Luthans, B. C., Luthans, K. W., & Jensen, S. M. (2012). The impact of business school students’ psychological capital on academic performance. Journal of Education for Business, 87(5), 253–259.

Luthans, F., Norman, S., Avolio, B., & Avey, J. (2008). The mediating role of psychological capital in the supportive organizational climate-employee performance relationship. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29, 219–238.

Luthans, F., & Youssef, C. M. (2004). Human, social, and now positive psychological capital management. Organizational Dynamics, 33, 143–160.

Luthans, F., Youssef, C. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2007b). Psychological capital: Developing the human competitive edge. New York: Oxford University Press.

MacKinnon, A., Jorm, A. F., Christensen, H., Korten, A. E., Jacomb, P. A., & Rodgers, B. (1999). A short form of the Positive and Negative Affect schedule: Evaluation of factorial validity and invariance across demographic variables in a community sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 27, 405–416.

Masten, A. S., & Reed, M. G. J. (2002). Resilience in development. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 74–88). New York: Oxford University Press.

Murray, A. J., Pirola-Merlo, A., Sarros, J. C., & Islam, M. M. (2010). Leadership, climate, psychological capital, commitment, and wellbeing in a non-profit organization. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 31(5), 436–457. doi:10.1108/01437731011056452.

Riolli, L., Savicki, V., & Richards, J. (2012). Psychological capital as a buffer to student stress. Psychology, 3(12A), 1202–1207.

Salanova, M., Schaufeli, W. B., Martinez, I. M., & Breso, E. (2010). How obstacles and facilitators predict academic performance: The mediating role of study burnout and engagement. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 23, 53–70.

Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4, 219–247.

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (2001). Optimism, pessimism, and psychological well-being. In E. C. Chang (Ed.), Optimism and pessimism: Implications for theory, research, and practice (pp. 189–216). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., & Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Review of Education, 35(3), 293–311.

Simons, J. C., & Buitendach, J. H. (2013). Psychological capital, work engagement and organisational commitment amongst call centre employees in South Africa. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology/SA Tydskrif vir Bedryfsielkunde, 39(2), 1–12.

Siu, O. L., Bakker, A. B., & Jiang, X. (2014). Psychological capital among university students: Relationships with study engagement and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 979–994. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9459-2.

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., & Furrer, C. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: Conceptualization and assessment of children’s behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69, 493–525. doi:10.1177/0013164408323233.

Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., et al. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measures of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 570–585.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Datu, J.A.D., Valdez, J.P.M. Psychological Capital Predicts Academic Engagement and Well-Being in Filipino High School Students. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 25, 399–405 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-015-0254-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-015-0254-1