Abstract

This study examines how pre-service ICT teachers who are equipped with technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge, meet challenges in their teaching practices. This study aims to portray Turkish elementary ICT teachers’ characteristics regarding their perceptions about teaching and their competencies. The data were collected by administering questionnaires to a total of 1,568 pre-service teachers. Moreover, 33 pre-service ICT teachers were interviewed, and 8 pre-service classroom observations were conducted to gain an in-depth understanding of the participants. Lesson plans were also analyzed during the data collection process. The results showed that the perceptions of the pre-service ICT teachers were generally positive about teaching. However, some negative points were also identified in their perceptions and competencies. The results of this study might shed light on who chooses ICT teaching as a profession, how ICT teachers are educated, and what career paths they follow.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The integration of technology into today’s classrooms is indispensible. When teachers choose to use technology in the classroom, a marked change may occur in student learning (Chai 2010). Morrison and Lowther (2004) illustrate this by stating that computers make a difference in student learning provided that teachers are mindful of the way they make their students use computer technology in the classroom. Similarly, Ertmer (2005) reports that although more teachers integrate technology into their educational activities, the way they implement this still remains a question. For instance, several studies found that even though teachers used technology in their basic level tasks, they failed to integrate it into more complex activities (Barron et al. 2003; Ertmer 2005). Turkey is not an exception in this situation. While almost all elementary schools provide computer-assisted education (OECD report 2005), it is questionable whether computers are being used effectively in Turkish classrooms (Yildirim 2007). In a study conducted in Turkey, Yildirim (2007) concluded that teachers’ views and capabilities, their computer literacy levels and attitudes toward technology affected the integration of technology into their classes. Since 1997, great efforts have been made in Turkey to inform teachers about Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) via pre-service and in-service training programs to make curricula more ICT-based, and to spread guidance and consultation services throughout the Country (OECD report 2005). ICT teachers are expected to perform a key role in the integration of technology in schools across Turkey. Discovering the characteristics of pre-service ICT teachers is a worthwhile effort as it will not only shed light on their education, but also help ensure effective integration of technology in teaching and learning environments.

ICT Teacher Training

As a result of the recent developments in technology, the focal point of technology integration has shifted from learning about ICT to learning through ICT. This has also focused the interest of teachers on how to teach both inside and outside the school using the Internet or educational software incorporated into students’ assignments (EURYDICE 2001; Law and Plomp 2003). Because of this shift, the role of ICT teachers has also changed. According to Law and Plomp (2003), the roles and practices of teachers who are responsible for integrating technology into education differ from Country to Country. As mentioned in Law and Plomp (2003), schools in the developed world employ a computer-related person to provide technical or instructional support to their users. In the USA, for example, many schools have a computer or technological supervisor. These members of staff also play an active role in integrating technology into education (Anderson and Dexter 2003). Similarly, the French government has decided that all schools will have computer coordinators to help teachers integrate technology into their teaching practices (Reigner 2003). These teachers also teach ICT as a separate subject at the secondary level, and they are educated about technology at large during their university training (EURYDICE 2001). Although elementary pre-service teachers in Europe take ICT-related courses during their training (EURYDICE 2001), a full-time coordinator is still deemed necessary at schools to integrate technology successfully into the curriculum (Lai and Pratt 2004).

Moreover, as there is a need for ICT teachers in many Countries (Davis et al. 2009; Hinostroza 2008), in Turkey there is also a huge demand for ICT teacher training with the common use of ICT in schools. Currently, the provision of education in Turkey continues to undergo significant changes in response to the changing technological environment. The Higher Education Council redesigned the curricula of the Faculties of Education in 1998. At that time, Computer Education and Instructional Technology (CEIT) departments opened within the Faculties of Education of various universities to pave the way for implementing rapidly developing technologies in schools (Orhan and Akkoyunlu 2003).

Teacher training in ICT education programs involves the acquisition of knowledge and skills in three domains: special subject matter domain, pedagogical domain, and cultural domain. The special subject teaching domain consists of 109 credit hours including such courses as computer-based education, web design, instructional technology, and material development. The pedagogical domain, on the other hand, consists of 30 credit hours including courses like classroom management, principles, and methods of instruction and teaching methods in computer education. The cultural domain, which consists of 13 credit hours, involves subjects such as history, literacy, and calculus. Teaching practicum and experiences are undertaken in the fourth year of the teacher training program in both fall and spring semesters. Students who graduate from CEIT departments after 4 years of education serve as ICT teachers in both state and private elementary schools. These teachers are mainly responsible for integrating technology into educational processes in schools.

The present study aims to portray elementary ICT teachers’ characteristics regarding their perceptions about teaching and their self-competencies about pedagogical and content knowledge. It is thought that the realization of efficient teaching practices depends directly on teachers’ perceptions and competencies since they are the practitioners of the curricula (Taylor 2006). This study examines how pre-service ICT teachers, who are equipped with technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge, meet challenges in their teaching practices. Hammond (2004) stresses that although there are various studies about the ICT use in teaching and learning processes, there is insufficient research about teaching ICT. Therefore, the results of this study might shed light on who actually chooses ICT teaching as a profession, how ICT teachers are educated, and what career paths they follow in Turkey.

Purpose of the Study

Teachers’ strengths, weaknesses, biases, personalities, and similar characteristics make them individuals (Kelly and Kelly 1985). As in other professions, teachers’ individual attributes are reflected in their work. In the field of education, this is particularly important as teacher perspectives may have an impact on student gains in the classroom. The literature about teachers’ characteristics claims a strong connection between teacher perceptions and practices (Labrana 2007; Macnab and Payne 2003). However, there aren’t many studies (Deryakulu and Olkun 2007; Hammond 2004) on computer or technology teachers’ characteristics as a pedagogical and subject matter knowledge and how these are manifested in their teaching practices.

In their framework of Technological, Pedagogical, Content Knowledge (TPACK), Mishra and Koehler (2006) define TPACK as connections and interactions of content knowledge, technological knowledge, pedagogical knowledge, and the transformation during the combination of those three domains. According to them, good teaching occurs when the introduction of technology into the existing pedagogy, and the content gives rise to new concepts and leads to the development of dynamic and transactional relationships between the domains as suggested by TPACK. In addition, according to (Voogt et al. 2013), teachers need to be competent in three areas, which are technology, content, and pedagogy, in order for them to integrate technology into their teaching activities. They state that teachers’ TPACK is also influenced by their perceptions. Therefore, teachers are required to take the interaction of technology, content, and pedagogy into consideration while integrating technology into their teaching practices (Angeli and Valanides 2009).

Similarly, Beijaard et al. (2000) state that teacher’s efficiency, motivation, and progress are influenced by their perception of teaching as a profession. Since the fulfillment of a school’s mission and vision, and students’ achievements and attitudes toward school depend on teachers’ beliefs about teaching and their practices, respectively, their beliefs about teaching are also significant factors in schools. Thus, teachers’ beliefs and perceptions of teaching should become an important focus of educational environment. Zehir-Topkaya and Uztosun (2012) also support the idea that self-perception is an important factor for career choice. In conclusion, teaching performance and learning outcomes expected from students are substantially affected by teachers’ perceptions of teaching and learning in their subject field (Koca and Sen 2006; Pajares 1992; Stipek et al. 2001).

Additionally, educators agree that integrating technology into the curriculum plays a major role in creating a rich instructional environment (Kulik 2002; Mishra and Koehler 2006; Teo et al. 2012; Webb and Cox 2004; Yildirim 2007). However, the availability of technology in classrooms is only one part of a bigger task (Hew and Brush 2007); the ultimate goal of integrating technology is to allow students to use it as a prominent facet of their classroom context. In Turkey, it is ICT teachers who are primarily responsible for integrating technology into classrooms besides informally mentoring other teachers in the use of technology. At the same time, the effective use of Information Technology (IT) in schools also depends on ICT teachers. Factors that are critical to the effective use of ICT in schools include ICT teachers’ competencies, their beliefs about teaching, their interaction with students and other teachers, and their problems regarding technology integration. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the characteristics of pre-service ICT teachers in terms of their perceptions and competencies in their teaching practices.

Method

In order to pursue the broader goal of this study, qualitative and quantitative methods were combined in a mixed method sequential explanatory design (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie 2004). The rationale behind using the mixed research method in this study was as follows:

-

(a)

It provides stronger data for conclusion through convergence and justification of the results

-

(b)

It adds understanding that might not otherwise be achieved with the use of a single method

-

(c)

It is used for the generalization of the results

-

(d)

It provides data triangulation to overcome the weaknesses or intrinsic biases and other problems caused by the use of a single method (Creswell 2003)

This study investigated the following main research questions:

-

(1)

What are the characteristics of elementary pre-service ICT teachers regarding their perceptions of teaching and their competencies (pedagogical and content knowledge)?

-

(2)

To what extent does ICT teaching occur in the classroom and what are the factors of an effective teaching and learning environment?

The quantitative part of the research focuses on pre-service ICT teachers’ perceptions about teaching and their self-perceived pedagogical and subject matter competencies. In order to obtain answers to the quantitative research questions, the researchers developed questionnaires and adapted the already existing instruments found in the literature review. The second part of this study, the qualitative phase, provides an in-depth understanding of ICT teachers’ perceptions toward teaching and their competencies. Interview and observation schedules were prepared by the researchers by way of taking expert opinions which were based on the related literature.

Instruments

Three instruments were used to collect data about participants’ perceptions of teaching, pedagogical competencies, and subject matter knowledge.

For the first instrument, previously developed instruments about teaching perceptions were examined by the researchers in order to measure perceptions about ICT teaching as a profession. As an appropriate instrument was not found for ICT teachers’ perceptions toward teaching, the researchers developed the Teacher Perception of Teaching (TPoT) as a new instrument based on the literature. This questionnaire comprised 2 sub-dimensions and 16 items. The first dimension was about general self-perceptions about the roles of ICT teachers (e.g., I believe that ICT teachers broaden the minds of their students) and included 9 items. The second dimension was about personal satisfaction with ICT teaching as a profession (e.g., ICT teaching is an exciting job for me) and included 7 items. The TPoT was a five-point Likert type questionnaire, on which 1 indicates “Strongly Disagree” and 5 indicates “Strongly Agree.” Pre-service teachers were asked to mark the best choice for them ranging from 1 to 5 for each item on the scale.

For the second instrument regarding self-perceived competencies, the pedagogical competency instrument including 22 items was used by employing the previous studies of the MoNE about pedagogical competencies. The instrument has three sub-sections:

-

(1)

“Recognition of students” section with 8 items (e.g., taking into consideration students’ learning styles and their individual differences in the lesson plan)

-

(2)

“The teaching process” section with 9 items (e.g., using alternative strategies for technologically supported environments)

-

(3)

“Measurement and evaluation” section with 5 items (e.g., using technology in the assessment of students)

For the third instrument with regard to measuring self-perceived subject matter knowledge, the researchers adapted the subject matter competency indicators prepared by the MoNE. From these indicators, a subject matter competency questionnaire was formed by the researchers by taking expert opinions. What was expected of the teachers with these competencies was: following innovations, developing themselves, and using their knowledge in the instructional environment (MoNE 2005). Subject matter competencies were also categorized into three levels with 23 items:

-

(1)

Basic level with 10 items, (e.g., installing and updating necessary software programs)

-

(2)

Middle level with 7 items, (e.g., selecting, evaluating, and using software related to learning development and teaching activities)

-

(3)

Mastery level with 6 items, (e.g., installing an appropriate network system and using this system to get connected to the other computers in the school)

For pedagogical competency and subject matter knowledge instruments, pre-service teachers responded to each statement on the 5-point Likert type scale on which 1 indicates “Not Competent,” 2 indicates “Somewhat Competent,” 3 indicates “Uncertain,” 4 indicates “Competent,” and 5 indicates “Highly Competent.” Pre-service teachers marked the best choice ranging from 1 to 5 for each item on the scale depending on their belief about their self-competencies.

The researchers conducted a pilot study to determine the reliability and validity of the questionnaires. The pilot study indicated that the Cronbach-alpha reliability was 0.90 for the perception, 0.96 for the pedagogical competency, and 0.94 for the subject matter. The overall Cronbach-alpha reliability of the questionnaire was 0.94.

Qualitative Procedure

In the qualitative procedure, data were gathered through interviews, observations, and document analysis after the completion of the quantitative data collection. Interviews and observations were conducted by the researchers during the teaching practice of the pre-service teachers in schools. Finally, the lesson plans prepared by the pre-service teachers during the teaching practice were evaluated by the researchers.

Interview schedules were prepared by the researchers. Structured interview questions focusing on pre-service ICT teachers’ views and thoughts about teaching as a profession while undertaking teaching practice in schools were used in the schedule. Before the final interview, the schedule was checked by the experts on the reliability and validity of the questions. Interviews were started with initial questions to obtain information about the interviewees and their general attitude toward technology integration. They also contained 12 main interview questions concerning ICT teaching perceptions, views about technology integration and pedagogical and subject matter knowledge (e.g., “What do you think about ICT teaching as a profession?,” “How do you design your lesson involving appropriate technological tools?,” and “How do you evaluate your students at the end of the lesson?”). The interview durations varied from 30 to 45 min depending on the participants’ responses. Interviews were recorded with the permission of the participants.

Regarding the observations, the researchers prepared the observation procedure and schedule by taking expert opinions to explore how pre-service ICT teachers integrate and transfer their pedagogical and technological knowledge into their teaching practice. Researchers conducted the observations by taking notes during the pre-service teachers’ teaching practice in the classroom environment. The following aspects were considered during the observations: (a) the context of the IT classroom, (b) pre-instructional process, (c) instructional process, (d) classroom management, and (e) post-instructional process. These are also related to the teacher competencies in the questionnaire administered in the quantitative phase of the study.

In addition to the interviews and observations, the lesson plans developed by pre-service teachers were analyzed and evaluated by the researchers in order to determine the type of technology used and the way teachers applied it in their teaching practice. The pre-service teachers developed instructional activities by utilizing technology and implemented them in their classes throughout the study. The lesson plans in which the pre-service teachers reported their teaching activities were analyzed by the researcher in terms of the following criteria:

-

(1)

Planning motivational activities for students in order to accomplish the goals and objectives of the lesson

-

(2)

Taking individual differences and learning styles of students into consideration during the planning process

-

(3)

Using methods and techniques appropriate for students’ ages, previous learning experience, and abilities

-

(4)

Creating opportunities for students to make connections between what they have learned and their lives

-

(5)

Planning activities for students’ participation (individual or group work, demonstrations, observations, experiments, panels, etc.)

Participants

The population of the current study was pre-service ICT teachers studying at CEIT departments in Turkey. The sample of the study was 1,695 CEIT students from 15 different universities in Turkey. Questionnaires designed to measure TPoT, self-perceived pedagogical, and subject matter competencies were sent by the researchers to all CEIT departments in Turkey. Although some departments were not willing to participate in the study, data were collected from 15 CEIT departments in different universities throughout Turkey along with the permission from their university administrative board. A total of 1,695 out of 2,110 questionnaires were completed. Of these 1,695 questionnaires, 97 were eliminated due to the missing data. Finally, 1,568 pre-service ICT teachers were participants of this study, 930 (59 %) of whom were male and 638 (41 %) of whom were female. Qualitative data were collected through interviews, observations, and the lesson plans of participants. For this purpose, the participants were selected as follows:

-

(1)

Fourth grade pre-service teachers were chosen as they had completed their teaching practice in schools

-

(2)

Among the quantitative results, participants’ demographics such as gender and perceptions of teaching were taken into account, that is, the equality of the number of the male and female students was provided, and the students who had high perceptions and low perceptions were both included in the qualitative phase

A total of 33 pre-service ICT teachers (18 males and 15 females) were interviewed voluntarily, and their lesson plans were analyzed. In addition to these, 8 pre-service classroom observations were conducted throughout the data collection

Demographics of the Participants

As can be seen in the Table 1, most pre-service teachers were aged between 20–21 (41 %) and 22–23 (42 %). The order of preferences shows the list of departments that pre-service teachers chose when they took the university entrance exam. The university admission system in Turkey involves a highly competitive university entrance exam. Each year, approximately 1.5 million high school graduates take this multiple-choice test, after which only 10 % of them enter university departments according to their results. Each high school graduate is then given a chance to choose departments, and these choices reflect candidates’ personal goals as well as their performance on the test. Students express their preferences in numerical order based on the points they receive from the university entrance exam. The results of the current study indicate that the institutions pre-service ICT teachers were attending were mainly within their first five choices (55.16 %).

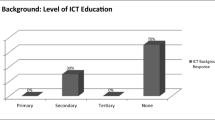

As for participants’ high school backgrounds, the secondary school experiences of the participants varied from general high school to science high school. Table 1 shows that 36.22 % of the participants graduated from Anatolian high schools and 32.51 % from vocational technical high schools. Regarding their parents’ educational background, 60.1 % of the mothers had achieved only a primary school degree and only 7.3 % held a university degree. As for the occupations of these pre-service teachers’ parents, the data illustrated that most mothers (74.7 %) were housewives, 7.7 % were retired, and 5.2 % were teachers. On the other hand, their fathers’ occupations were various: 32.1 % were retired, 17.6 % were self-employed, and 12.6 % were state employees.

Results

Quantitative Findings

Based on the pre-service teachers’ responses to the TPoT, the item which is “I think that ICT teachers contribute to the development of technological knowledge in the society” had the highest mean score (M = 3.97, SD = 0.95). The lowest mean score of the pre-service teachers was for the item, which is “In my opinion, other teachers (e.g., math, science, etc.) view ICT teachers as their role-models while incorporating technology into their classrooms” (M = 2.85, SD = 1.04) (Table 2).

For pedagogical competencies, according to the information obtained from the participants, the mean scores for the pre-service teachers varied from 2. 98 (e.g., checking the reliability and validity of the instruments) to 3.64 (e.g., listening to students and answering their questions sincerely) (Table 3).

Regarding the self-perceived subject matter competencies, based on the participants’ answers, the mean scores ranged from 2.82 (e.g., searching and using professional systems and databases to access and share information) to 4.12 (e.g., installing and updating necessary software programs and maintaining the system regularly) (Table 4).

The results showed that pre-service teachers’ perceptions of teaching, subject matter competencies, and pedagogical competencies are quite high and positive. However, pre-service teachers’ perceptions of teaching changed year by year during their undergraduate education. The finding is interesting in that their perceptions of teaching decrease in the third year and increase again in the fourth year (Table 5).

Regarding the gender differences in the related variables, the results of the study indicated that there were no statistically significant differences between male and female pre-service teachers’ perceptions of teaching besides their pedagogical competencies. However, there were statistical differences between male and female pre-service teachers’ subject matter competencies in favor of males, (Mean difference = 0.37 and p < 0.01).

Qualitative Findings

In order to analyze the notes from the interview and observation, Strauss and Corbin’s (1998) strategies, open coding, axial coding, and selective coding were used. After using these strategies, the themes and codes were extracted from the participants’ responses by taking the qualitative research questions into account. The resulting coding system and codes were reviewed by experts and peers. Reliability and validity were taken into consideration in all the phases of the research.

There are four professors in the validity committee. One is a specialist in qualitative research and one of them is also a specialist in educational administration. One of the other two is currently working as the chair of a CEIT department and the other is an instructor in a CEIT department, know the development process of the field and have mastered its theoretical framework. Each committee member reviewed codes by himself and then reviewed the codes together as a committee in order to provide the validity of the results.

In fact, the qualitative results provided more detailed and in-depth information about the characteristics of the pre-service teachers in terms of their perception and self-competencies than the quantitative results. The qualitative findings gathered from the participants about IT classes are summed up in the following table:

As seen in Table 6, the qualitative findings of the study generally supported the quantitative findings. On the other hand, some differences between the quantitative and the qualitative results were also identified.

Different from the quantitative results, the qualitative results showed that students’ concerns and motivation increased their perception of teaching; however, according to pre-service teachers’ thoughts, they were expected to act as if they were technical members of staff at schools. ICT teachers are considered to be an expert who knows everything about technology and technical service staff. Indeed, the anxiety of being a teacher and having to catch up with cutting-edge technology are the two factors that decrease their initial excitement toward teaching.

During the interviews, some pre-service teachers complained that the ICT teachers were regarded as technical service engineers, and worried about not being able to manage this job. For example one of them stated;

…It seems that working as an ICT teacher at schools is more difficult than their specified responsibilities. To me, it is not our job to mend the computers at schools or to sort out the problems of the computers of the school headmasters or the other teachers. At schools, we are considered to be technical staff and this actually makes me feel frightened…

According to the qualitative results, the pre-service ICT teachers were aware of the importance of informing people about technological advances and thus of being useful to society. They thought that they should act and develop themselves accordingly.

For instance, a male pre-service teacher expressed his opinion:

…I think the more we adopt technology and the more we pursue every technological nuance, the more useful we will become to society. We should be self-sacrificed and distinct from the other people…

Discussion

Background of the ICT Teachers

An analysis of the background characteristics gave insights into those participants currently entering the field of ICT teacher education in Turkey. The results of the study showed that the majority of the pre-service ICT teachers who participated in this study were male although it has been reported in some studies (Coultas and Lewin 2002; Richardson and Watt 2006; Saban 2003) that female participants prefer teaching more than male participants do. Since ICT teaching generally has regarded as a technical department, male students might have preferred the ICT teaching department more than female students. Another reason may have been the fact that the majority of the students in the department come from vocational high schools whose student population is more predominantly male.

The results illustrate that the majority of the participants came from a relatively moderate socio-economical background. For example, the mothers of the participants were generally housewives and primary school graduates while the majority of the fathers were either retired or civil servants, and almost half were primary school graduates. The percentage of the fathers holding a higher education degree was higher when compared to that of the mothers. In parallel to this, Coultas and Lewin (2002) studied the background characteristics of student teachers in four developing Countries and found that the majority of their mothers were housewives with limited education. Similar studies conducted previously also indicate that the socio-economic status of the pre-service teachers in Turkey is mostly at the lower-middle level (Saban 2003; Seferoğlu 2004).

Perceptions of ICT Teaching

Based on the results of the study, the pre-service teachers have both positive and negative views about the profession. For example, they perceived ICT teachers as people who persuade students to research and contribute to the development of the technological knowledge of the society since they are aware of the importance of technology. Additionally, the results of this study show that most pre-service teachers placed the CEIT department among their first five choices in the university exam. This is an indication that pre-service teachers chose this department consciously and willingly. Therefore, it can be concluded that the pre-service teachers had a high perception of their profession during the early years of their education. On the other hand, according to the results of this study, although the pre-service teachers’ opinion of the profession was generally positive, there occurred a change in these perceptions over the years. Stress about finding a job upon graduation could be a contributing factor to this decrease in interest. Thus, the knowledge and perception of pre-service teachers before starting to teach is an indicator of their professional career (Kagan 1992; Taylor 2006).

When the perceptions of the teachers are positive, their performance in teaching is elevated accordingly. Other studies (Fajet et al. 2005; Minor et al. 2002) have also emphasized that positive thinking about the profession is a shared characteristic of qualified teachers. For example, in a study with 120 pre-service teachers, Fajet et al. (2005) concluded that qualified teachers displayed eagerness for the profession.

The present study found that although the pre-service teachers believed that ICT teaching was an enjoyable and easy profession, they considered the conditions of ICT teaching not to be very appealing, and it needed improvement. They felt that other teachers in schools perceived them as technical staff. In Turkey, the actual responsibilities of ICT teachers are to serve as ICT teachers and to integrate technology into education in schools. Besides their teaching role in schools, they act as a mentor for other teachers to use the current and developing technology in their subject field and train them for the innovations in the instructional technology. In other words, their responsibilities include only educational purposes, and this is what they are specifically trained for. But, in practice, ICT teachers in schools take on additional responsibilities such as solving technical problems, assisting school administrators and teachers as if they were technical staff in schools as well as their actual responsibilities. ICT teachers should be seen as technological consultants or advisors instead of acting solely as ICT teachers or technical staff. For example, the teachers from other fields mostly consider ICT teachers as people who are responsible for “assisting teachers in the e-school environment” as an extracurricular role. (Göktaş and Topu 2012) concluded that all staff in schools commonly expect ICT teachers to provide assistance to them to deal with hardware and software problems. The basic reasons behind those expectations might be lack of the qualified staff responsible for hardware and software, inadequate ICT literate staff in schools such as administrators and teachers, and ambiguity in ICT teachers’ job descriptions.

Regarding gender differences in perceptions of teaching, it was observed that although the perceptions of male pre-service teachers were more positive than those of female teachers, a significant difference did not exist between the two groups. However, some previous studies (Ghaith and Shaaban 1999; Minor et al. 2002; Saban 2003) reported that female teachers had higher teaching concerns than male teachers. The ICT classes’ atmosphere has a negative effect on the perceptions of female teachers as it is a challenging environment for them. This could be because of distinct personality traits that the women ICT teachers possess. Pre-service ICT teachers affirmed these in the interviews stating that female teachers, especially those who are not vocational high school graduates, can have difficulty adapting to the atmosphere very easily.

Pedagogical Competencies

The results of this study illustrated that pre-service ICT teachers’ pedagogical competencies increase throughout their education. Similarly, Nettle (1998) highlights that the courses given in universities contribute to student teachers’ progress in the profession. On the other hand, the qualitative results showed that pre-service teachers feel inadequate in terms of competence in some cases. One example of this is the difficulty they face when assessing students during their classroom practice. The reason for this might be that the measurement and evaluation of students in the ICT classes requires more time for practice since computer classes are practice-based. Moreover, pre-service teachers do not have enough time for assessment. They don’t have the opportunity to use suitable measurement tools for student assessment, either.

The results of the study conducted by Chong et al. (2010) showed that as pre-service teachers completed the teacher training program, their perceptions about their knowledge and skills of facilitating teaching and learning, classroom management, and lesson planning significantly increased. However, some knowledge and skills as perceived by them such as their skill levels of pedagogical care and concern for their students remained the same by the end of the program. In the interviews and during the observations, it was noted that pre-service ICT teachers faced disciplinary difficulties in the ICT classes, and the design of the ICT classes made communication with students more complicated. Offering pre-service teachers some extra pedagogy and subject matter courses (e.g., child psychology, educational psychology, and educational philosophy) as well as training on measurement and evaluation during their university years might help them sort out this problem. In the same way, Darling-Hammond (2000) concluded that a variety of courses offered at university, such as theoretical foundations of education, learning theory, instructional methods, and classroom management, have positive effects on the performance of pre-service teachers as well as on their students’ achievement. Moreover, it is true that pre-service teachers are expected to behave like experienced teachers and to adapt to the school culture immediately, which is not at all realistic. Researchers claim that pre-service teachers know the rules that they need to follow when teaching, but they have difficulties in practice (Mishra and Koehler 2006). As classroom experience is essential for successful teaching, additional teaching practice could be undertaken before pre-service teachers start teaching at schools. This experience might be gained during university years and through in-service training.

Another result indicated that pre-service ICT teachers experience some difficulties in integration process of technology into educational environments. ICT teachers for example, should take into consideration the diverse features of students such as handicapped or gifted students in the planning and development processes of instructional materials. Those are the significant skills that pre-service ICT teachers should gain before graduation. The integration of ICT into schools also depends on teachers’ thoughts about pedagogy and use of technology in the classroom environment since their thoughts and knowledge have an influence on the integration of ICT into schools (Gurcay et al. 2013).

Regarding gender, although female pre-service teachers saw themselves to be pedagogically more competent than male teachers, no statistical difference was found between the two sexes. In the literature, it is stated that female teachers willingly choose and enjoy the teaching profession and are especially good at the field of pedagogy (Minor et al. 2002; Peretz et al. 2003).

Subject Matter Competencies

Our findings show that pre-service ICT teachers’ subject matter knowledge increase during the years in teacher education programs. Moreover, the results showed that pre-service ICT teachers felt quite competent in certain issues, such as setting up computer software, updating or deleting it from the computer, and system settings. However, they did not seem to update themselves with regard to technology. Meanwhile, the pre-service ICT teachers feel incompetent in ICT teaching as the students need special education (physically and mentally handicapped or gifted students). Seferoğlu (2004) attributed this to the fact that university curricula include no courses on special education, and stated that the MoNE needs to continuously overview teacher competencies, and set special concerns and competencies.

Based on the views of pre-service ICT teachers, computers should be used in other classes such as math and science as well. This might encourage other teachers to cooperate with ICT teachers to find a way to adapt computers and technology to their lessons. In addition, ICT classes in schools should be open outside the school hours to enable both students and teachers to use technology as in developed Countries (Becta 1998; Law and Plomp 2003).

Our study found that as pre-service ICT teachers progress through their university education, they become competent both in subject matter and in pedagogic domains. This finding confirms that there is a significant relationship between pre-service ICT teachers’ competencies and their pedagogical belief and their embraced use of ICT (Cahill and Skamp 2003; Chai 2010). Arends (2001) states that teachers are expected to have advanced preparations and demonstrate their knowledge of both subject matter and pedagogy. This result also coincides with Mishra and Koehler’s (2006) model TPCK that the transfer of content knowledge with appropriate technology is important, and it will be much more meaningful if it is compatible with pedagogical knowledge. Since they will 1 day be ICT teachers in schools and one of their most important roles will be to integrate technology, particularly computer technology, into educational settings, pre-service ICT teachers should be competent both in subject matter and in pedagogic domains before graduating. Without competent teachers in the subjects and the process of education, no educational or industrial education program can be fully successful (Fajet et al. 2005).

Conclusions and Implications

It is remarkable to integrate technology into curriculum in order to create rich learning environments in schools (Mishra and Koehler 2006; Teo et al. 2012; Yildirim 2007). The successful integration of technology into curriculum highly depends on ICT teachers, who are trained for this purpose, as well as technological capabilities of schools in Turkey. Therefore, this study investigated pre-service ICT teachers’ characteristics regarding their perceptions about teaching and their pedagogical and subject matter knowledge. According to Mahijos and Maxson (1995) pre-service teachers are influenced by their own experience as students (e.g., their relations with their teachers), as well as family history (e.g., the socio-economic status of the family), the social environment they live in, the values they hold, their attitudes to the profession of teaching, and their ideas about education in general.

The results revealed that pre-service ICT teachers can use technology effectively in their instructional activities. They can use technology in student learning of subject matter using a variety of techniques. Besides, they can utilize technological resources to improve instructional practices and maximize student learning in multimedia environments. The use of instructional techniques enhanced with audio visual materials, and the new technology in projects allows the individual features of students to be taken into consideration by the teachers and provides the creation of a rich learning environments, that is, affecting instructional processes positively (Lowther et al. 2008). In addition, (Webb and Cox 2004) emphasized that ICT-based learning environments require teachers to have more pedagogical responsibilities. In addition, their research results showed that the views of the teachers about ICT significantly affect their pedagogical responsibilities. According to a recent study (Chai et al. 2013) there is a strong relationship between teachers’ TPACK and their belief about pedagogy.

The results of this study are also in parallel to the ISTE standards for teachers (ISTE 2009a) to integrate technology into education. According to the ISTE (2009a) standards, teachers should be models facilitating students’ learning and encouraging their creativity in the information age. Besides, teachers should encourage students to have responsibilities in studying and learning as digital citizens. Therefore, teachers need to have required competencies for a successful integration of technology and lead to the use of the technology by students for a qualified education. A successful integration of technology into educational settings also depends on the pedagogical knowledge of teachers.

In their study regarding pre-service teachers’ technological pedagogical knowledge (TPK) and transformation of this knowledge into their teaching practices, Gao et al. (2011) found that as pre-service teachers’ knowledge about student learning and use of technology in classroom increases, they use technology more effectively in their teaching practices. Researchers underlined that the relationships between the appropriate usage of technology, content and pedagogy are indicators of qualified teaching (Mishra and Koehler 2009; Angeli and Valanides 2009). According to Mishra and Koehler (2006), TPACK is the basis of effective teaching using technology. Therefore, it is required for teachers to know how to use technology in teaching concepts, how technology helps to solve some problems encountered by students, and how technology can be used to support or construct new knowledge based on existing knowledge. Thus, Archambault (2011) suggests that there is a need to add new modules into the already existing courses or create new courses and teaching experiences in teacher training programs in order for pre-service teachers to have required knowledge and skills for the successful integration of technology into their future courses. In this context, Graham et al. (2012) highlighted that the TPACK provides a vision for the use of technology in supporting both general pedagogical practices and content-specific pedagogical practices as appropriate with the goals of teacher training programs aiming to train teachers for the next generation.

The previous studies conducted indicate that teachers’ pedagogical reasoning significantly depends on their views about the importance of ICT for learning and the characteristics of successful learning environments (Leng 2011; Webb and Cox 2004). Loveless (2011), concluded that the interest of teachers in developing technology and their use of the technology for teaching in alignment with the pedagogy is one of the success factors in educational environments. Thus, teachers of other subjects are needed to be encouraged by ICT teachers to use developing technology for educational purposes. Instead of viewing technology just as computers and their parts, there are better ways of integrating technology into all courses and using it better. The efficient and effective use of technology cannot, apparently, be guaranteed just by providing technological tools for schools. Schools should conduct needs assessments in order to determine their requirements regarding the use of technology (Yildirim 2007) and ensure constant cooperation between ICT teachers and other teachers in the school. The ICT teachers, who are well-equipped for this matter, can help other teachers directly because the teachers of other subjects may not have enough knowledge about existing technological tools.

According to the ISTE (2009b) standards, ICT teachers, as technology leaders in schools, help other teachers in facilitating learning for all students in school, enriching instruction, providing learning experience related to the subject, and using technology efficiently in assessment processes. In addition, ICT teachers are needed to encourage other teachers to follow the developments in ICT. To meet these standards, ICT teachers should serve as ICT coordinator teachers in schools as is the case in many other Countries (Law and Plomp 2003), and these coordinators should be employed by every school. Hammond (2004) highlights that the lack of ICT teachers in schools continues, and there is a need to improve ICT teachers’ career opportunities.

Furthermore, this study has elicited important information about the elementary ICT teacher training programs undertaken for technology integrators in schools in Turkey. Researchers claimed that the use of information and communication technology is central to teachers’ preparation in planning for education and educational reforms (Ertmer 2005; ISTE 2009a; Mishra and Koehler 2006). With this in mind, the studies (Davis 2008; Zhao and Frank 2003) showed that ICT enabled teachers to easily change their teaching and learning activities with the organizational support and change. For this reason, Davis et al (2009) report teacher development programs such as classroom-based programs including with ICT coordinators to promote organizational support and leadership in schools.

The findings of this study also have implications for future research. Similar studies about technology teacher education programs may be conducted in different countries for comparative purposes. Also, in-service ICT teachers’ experience should be examined in order to understand their needs and challenges in technology education as they gain more experience and skills.

References

Anderson, R. E., & Dexter, S. (2003). National policies and practices on ICT in education: United States. In T. Plomp, R. Anderson, N. Law, & A. Quale (Eds.), Cross-national information and communication technology policies and practices in education (pp. 569–580). Greenwich: Connecticut: IAP.

Angeli, C., & Valanides, N. (2009). Epistemological and methodological issues for the conceptualization, development, and assessment of ICT-TPCK: Advances in technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK). Computers & Education, 52, 154–168.

Archambault, L. (2011). The practitioner’s perspective on teacher education: Preparing for the K-12 online classroom. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 9(1), 73–91.

Arends, R. I. (2001). Learning to teach (5th ed.). NewYork: McGraw-Hill Companies.

Barron, A. E., Kemker, K., Harmes, C., & Kalaydjian, K. (2003). Large-scale research study on technology in K–12 schools: Technology integration as it relates to the National Technology Standards. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 35, 489–507.

Becta. (1998). How learning is changing: information and communications technology across Europe. Coventry: British Educational Communications and Technology Agency.

Beijaard, D., Verloop, N., & Vermunt, J. D. (2000). Teachers’ perceptions of professional identity: An exploratory study from a personal knowledge perspective. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16, 749–764.

Cahill, M., & Skamp, K. (2003). Completed first year: Novice’s perceptions of what would improve their science teaching. Australian Science Teachers Journal, 49(1), 6–17.

Chai, S. C. (2010). The relationships among Singaporean pre-service teachers’ ICT competencies, pedagogical beliefs and their beliefs on the espoused use of ICT. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 19(3), 387–400.

Chai, C. S., Chin, C. K., Koh, J. H. L. & Tan C. L. (2013). Exploring Singaporean Chinese language teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge and its relationship to the teachers’ pedagogical beliefs. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 1-10, Retrieved May 19, 2013, from http://springerlink.bibliotecabuap.elogim.com/article/10.1007/s40299-013-0071-3.

Chong, S., Wong, A. F. L., Choy, D., Wong, I. Y.-F., & Goh, K. C. (2010). Perception changes in knowledge and skills of graduating student teachers: A Singapore study. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 19(2), 333–345.

Coultas, J. C., & Lewin, K. M. (2002). Who becomes a teacher? The characteristics of student teachers in four countries. International Journal of Educational Development, 22, 243–260.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Teacher quality and student achievement: A review of state policy evidence. Educational Policy Analysis Archives, 8. Retrieved July 22, 2012, from http://epaa.asu.edu/epaa/v8n1.

Davis, N. E. (2008). How may teacher learning be promoted for educational renewal with IT? In J. Voogt & G. Knezek (Eds.), International handbook of information technology in education. Amsterdam: Kluwer Press.

Davis, N., Preston, C., & Sahin, İ. (2009). ICT teacher training: Evidence for multilevel evaluation from a national initiative. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40(1), 135–148.

Deryakulu, D., & Olkun, S. (2007). Analysis of computer teachers’ online discussion forum messages about their occupational problems. Educational Technology & Society, 10(4), 131–142.

Ertmer, P. A. (2005). Teacher pedagogical beliefs: The final frontier in our quest for technology integration? Educational Technology Research and Development, 53(4), 25–39.

EURYDICE. (2001). Basic indicators on the Incorporating of ICT into European Education Systems- facts and figures. Brussels: European Commission.

Fajet, W., Bello, M., Leftwich, S. A., Mesler, J. L., & Shaver, A. N. (2005). Pre-service teachers’ perceptions in beginning education classes. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21, 717–727.

Gao, P., Tan, S. C., Wang, L., Wong, A., & Choy, D. (2011). Self- reflection and pre-service teachers’ technological pedagogical knowledge: Promoting earlier adoption of student-centred pedagogies. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27(6), 997–1013.

Ghaith, G., & Shaaban, K. (1999). The relationship between perceptions of teaching concerns, teacher efficacy, and selected teacher characteristics. Teaching and Teacher Education, 15, 487–496.

Göktaş, Y., & Topu, F. B. (2012). ICT teachers’ assigned roles and expectations from them. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 12(1), 473–478.

Graham, C. R., Borup, J., & Smith, N. B. (2012). Using TPACK as a framework to understand teacher candidates’ technology integration decisions. Journal of Computer Assisted learning, 28(6), 530–546.

Gurcay, D., Wong, B., & Chai, C. S. (2013). Turkish and Singaporean pre-service physics teachers’ beliefs about teaching and use of technology. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 22(2), 155–162.

Hammond, M. (2004). The peculiarities of teaching information and communication technology as a subject: a study of trainee and new ICT teachers in secondary schools. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 13(1), 29–42.

Hew, K. F., & Brush, T. (2007). Integrating technology into K-12 teaching and learning: Current knowledge gaps and recommendations for future research. Education Technology Research & Develeopment, 55, 223–252.

Hinostroza, H. (2008). Technology and learning-teacher learning-service teacher training. In E. Baker & B. Mcgraw (Eds.), International encyclopaedia of education (3rd ed.). New York: Springer.

ISTE. (2009a). National educational technology standards (NETS) for teachers. Retrieved June 14, 2012, from http://www.iste.org/standards/nets-for-teachers.aspx.

ISTE. (2009b). NETS for coaches. Retrieved June 14, 2012, from http://www.iste.org/standards/nets-for-coaches.aspx.

Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Journal Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14–26.

Kagan, D. M. (1992). Professional growth among pre-service and beginning teachers. Review of Educational Research, 62(2), 129–169.

Kelly, J., & Kelly, M. (1985). The successful elementary teacher. Baltimore: University Press of America Inc.

Koca, S. A., & Sen, A. I. (2006). The beliefs and perceptions of pre-service teachers enrolled in a subject-area dominant teacher education program about effective Education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22, 946–960.

Kulik, J. (2002). School mathematics and science programs benefit from instructional technology. Washington, DC: National Science Foundation. Retrieved April 10, 2012, from http://www.nsf.gov/sbe/srs/infbrief/nsf03301/start.htm.

Labrana, C. M. (2007). History and social science teachers’ perceptions of their profession: A phenomenological study. The Social Studies, 98(1), 20–24.

Lai, K. W., & Pratt, K. (2004). Information and communication technology (ICT) in secondary schools: The role of the computer coordinator. British Journal of Educational Technology, 35(4), 461–475.

Law, N., & Plomp, T. (2003). Curriculum and staff development for ICT in Education. In T. Plomp, R. Anderson, N. Law, & A. Quale (Eds.), Cross-national information and communication technology policies and practices in education (pp. 15–31). Greenwich: Connecticut: IAP.

Leng, N. W. (2011). Reliability and validity of an information and communications technology attitude scale for teachers. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 20(1), 162–170.

Loveless, A. (2011). Technology, pedagogy and education: Reflections on the accomplishment of what teachers know, do and believe in a digital age. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 20(3), 327–342.

Lowther, D., Strahl, J. D., Inan, F. A., & Ross, S. M. (2008). Does technology integration “work” when key barriers are removed? Educational Media International, 45, 195–213.

Macnab, D. S., & Payne, F. (2003). Beliefs, attitudes and practices in mathematics teaching: Perceptions of Scottish primary school student teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching, 29(1), 55–68.

Mahijos, M., & Maxson, M. (1995). Capturing pre-service teachers’ beliefs about schooling, life and childhood. Journal of Teacher Education, 46(3), 192–199.

Minor, L. C., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Witcher, A. E., & James, T. I. (2002). Pre-service teachers’ educational beliefs and their perceptions of characteristics of effective teachers. The Journal of Educational Research, 96(2), 116–127.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2009). Teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge and learning activity types: Curriculum-based technology integration reframed. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 41(4), 393–416.

MoNE. (2005). Information technology teachers’ subject matter competencies. MoNE, Ankara. February 15, 2012, from http://otmg.meb.gov.tr/alanbt.html.

Morrison, G. R., & Lowther, D. L. (2004). Integrating computer technology into the classroom (3rd ed.). Columbus: Pearson Merrill Prentice Hall.

Nettle, E. B. (1998). Stability and change in the beliefs of student teachers during practice teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 14(2), 193–204.

OECD report. (2005). National education policy review background report. Ankara. Retrieved August 10, 2012, from http://digm.meb.gov.tr/uaorgutler/OECD/OECD_onrapor_ingMart06.pdf.

Orhan, F., & Akkoyunlu, B. (2003). Profiles and opinions of the computer formative teachers’ on the difficulties they have faced during the applications. Hacettepe Journal of Education, 24, 90–100.

Pajares, F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62, 307–332.

Peretz, B. M., Mendelson, N., & Kron, F. W. (2003). How teachers in different educational contexts view their roles. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19, 277–290.

Reigner, C. (2003). National policies and practices on ICT in education: France. In T. Plomp, N. Law, & A. Quale (Eds.), Cross-national information and communication technology policies and practices in education (pp. 233–247). Greenwich: Connecticut: IAP.

Richardson, P. W., & Watt, H. M. (2006). Who chooses teaching and why? Profiling characteristics and motivations across three Australian Universities. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 34(1), 27–56.

Saban, A. (2003). A Turkish profile of prospective elementary school teachers and their views of teaching. Teacher and Teacher Education, 19, 829–846.

Seferoğlu, S. S. (2004). Teacher candidates’ evaluation of their teaching competencies. Hacettepe University Journal of Education, 26, 131–140.

Stipek, D. J., Givvin, K. B., Salmon, J. M., & MacGyvers, V. L. (2001). Teachers’ beliefs and practices related to mathematics instruction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 213–226.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Taylor, A. (2006). Perceptions of prospective entrants to teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(4), 451–464.

Teo, T., Ursavaş, F. Ö., & Bahçekapili, E. (2012). An assessment of pre-service teachers’ technology acceptance in Turkey: A structural equation modeling approach. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 21(1), 191–202.

Voogt, J., Fisser, P., Pareja, N., Tondeur, J., & van Braak, J. (2013). Technological pedagogical content knowledge. A review of the literature. Journal of Computer Assisted learning, 29(2), 109–121.

Webb, M., & Cox, M. (2004). A review of pedagogy related to information and communications Technology. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 13(3), 235–286.

Yildirim, S. (2007). Current utilization of ICT in Turkish basic education schools: A review of Teacher’s ICT use and barriers to integration. International Journal of Instructional Media, 34(2), 171–186.

Zehir-Topkaya, E., & Uztosun, M. S. (2012). Choosing teaching as a career: Motivations of pre-service English teachers in Turkey. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 3(1), 126–134.

Zhao, Y., & Frank, K. A. (2003). Factors affecting technology uses in schools: an ecological perspective. American Educational Research Journal, 40(4), 807–940.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cakir, R., Yildirim, S. Who are They Really? A Review of the Characteristics of Pre-service ICT Teachers in Turkey. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 24, 67–80 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0159-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0159-9