Abstract

This study endeavors to reveal senior high school students’ motivational orientations in attending cram schools, how they approach English learning there, and to what extent they find cram schooling facilitates their English learning. Questionnaires were distributed to 365 respondents, followed by four focus group interviews. Results show that instrumental and integrative motivation play crucial roles in students’ motivation for learning English at a cram school. Cram school learners mostly adopted passive role and rote learning, which was associated with surface learning approach. A large percent of participants believed attending cram schools was beneficial in helping them achieve higher grades in English exams and gain admission to a university. On the other hand, they did not find cram schooling to be as helpful in the enhancement of their competence or confidence in using English. In view of this, suggestions are highlighted as to how CEE should work out a more holistic evaluation to reflect English learners’ needs in communicating in English more competently and confidently.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cram schools are commonly found in many Asian countries, where academic competition is keen from the elementary to high school level. Cram schooling is particularly prevalent in certain countries like Japan, China, Korea, and Taiwan. Deeply influenced by Confucianism, nowadays, a majority of Taiwanese still show respect to people known for their academic achievement. Parents generally set high expectations and are highly involved with their children’s learning (Li 2003). Parents try their best to provide children with “good education” in the hope that their children can “win from the starting point.” Many choose to send children to cram schools with the belief that cram schooling can successfully boost academic achievements.

Cram schools (buxiban) in Taiwan are specialized fee-paying private schools that provide intensive courses of specific subjects to train tutees to enhance their academic ability or professional competence. Throughout Taiwan, there are different types of cram schools with various teaching objectives set for tutees’ diverse needs. For example, some cram schools are established to meet the need of general public who want to enhance their competition in the job market or continue lifelong learning.

For years, cram schooling has been viewed by educators and reformers as a major source of pressure for students preparing for CEE. According to Lin and Chen (2006), more than 80 % of senior high school students in Taiwan had the experience of attending cram schools. In view of this, one of the themes of educational reform by the Taiwan Ministry of Education (MOE) has been to reduce students’ need for “cram schooling” (MOE 2002). Despite MOE’s efforts, still many students attend cram schools, and the number of cram schools has increased considerably in the past decade.

As Fig. 1 shows, the number of cram schools in Taiwan has increased from 6,806 to 18,828 from 2002 to 2011 (MOE 2011). It is thus worth investigating why students choose to spend extra tuition and sacrifice their own time at cram school.

This study will focus only on cram schools aiming to prepare senior high school students for College Entrance Examination (CEE). Being academically oriented, these cram schools are set up to enhance students’ academic performance in “major subjects,” such as English, science, and mathematics. Their eventual goal is to help students successfully get admission to an ideal university. Although these cram schools provide courses for most exam subjects included in CCE, the present study will examine only how students approach English learning there.

Literature Review

Motivational Orientations

Over the past few decades, motivational orientations have been the focus of discussions and research in the language learning literature. Motivation mainly concerns the direction and magnitude of behavior, which, accordingly to Dörnyei (2001), is “responsible for why people decide to do something, how long they are willing to sustain the activity, and how hard they are going to pursue it” (p. 8). Motivation in second language acquisition is defined by Gardner (1985) as “the combination of effort plus desire to achieve the goal of learning the language plus favourable attitudes toward learning the language” (p. 10). These arguments indicate the complexity of motivation as well as its role in language learning. A substantial literature has seen the motivational orientations as determinants that affect the quality or achievements of student learning. For example, Linnenbrink and Pintrich (2002, p. 313) asserted that student motivation, which can be conceived of as a multifaceted construct with different components, is a decisive enabler for academic success. Saville-Troike (2006) pointed out that students who are more motivated are able to learn a new language better.

Numerous perspectives and issues have been developed to differentiate various types of motivation in the area of language learning. Gardner and Lambert (1972), who identified and proposed integrative and instrumental motivation as two major kinds of motivation related to second language learning, have laid the foundation stone for a large body of research on motivation. Integrative motivation reflects the learners’ desire or willingness to master the target language for knowing more about the target culture. Integrative-oriented learners make efforts to integrate themselves within the target language community and to communicate with members of that community (Gardner and Gilksman 1982).

Instrumental orientations, on the other hand, place emphasis on “the practical value and advantages of learning a new language” (Lambert 1974, p. 98). Instrumental motivation is characterized by a desire to gain social recognition or economic advantages through learning or knowing the target language. Language learners with instrumental motivation tend to learn the target language for utilitarian benefits, such as better academic achievements or career development. Gardner and MacIntyre (1991, p. 57) investigated the effects of integrative motivation and instrumental motivation on the learning of French and English vocabulary. The results demonstrated that both integrative and instrumental motivation have an energizing effect on students and could facilitate language learning.

Approaches to Learning

The approach to learning of students has been another topic of growing interest among educational researchers. Biggs (1993) proposed the 3P model to elaborate the relations between what teachers and students do as well as the nature of student learning outcomes. He concluded that there were three different types of learning approaches: deep approach, surface approach, and strategic or achieving approach.

A deep approach to learning is characterized by an intention to seek meaning of the material being studied by elaborating and transforming it. It is associated with a student’s active engagement with the subject matter (Spencer 2003). Deep approach to learning is seen to be related to constructivist teaching, which enables learners to construct knowledge for themselves actively (Biggs and Moore 1993; Dart et al. 2000). Surface approach is characterized by memorization of information and procedures. It is associated with the traditional transmission model of teaching, in which information is transferred from teachers to learners. Surface learners tend toward accurate reproduction of facts and the material being studied through routine procedures. This type of approach is believed to produce lower quality outcomes, such as “fragmented learning” and “missing the point” of the materials (Biggs and Moore 1993; Prosser and Trigwell 1999).

Biggs (1987, p. 24) asserted that students who adopt a deep approach have an interest in the academic task and enjoy carrying out the task. They seek for the meaning from the task, personalize it and make it meaningful to not only their own experience but also the real world. In addition, they also relate the present task to their previous knowledge, trying to theorize about the task. On the other hand, it is generally agreed that students who adopt a surface approach view the task as a necessary imposition and a demand to be met to reach some other goal. Seeing parts of the task as discrete and irrelevant to each other, students using a surface approach reproduce the surface aspects of the task through the method of memorization. They adopt passive role in learning, often lack interest in the subject, and are probably motivated by fear of failure.

It is worth noticing that there has been a debate within the literature as to whether the simple dichotomy between deep and surface learning may seem over-simplified and implausible. Despite the criticism, the model remains to have strong influence on research into promoting student learning (Gibbs 1992). Some researchers asserted that outside factors, known as situational factors, such as an inherent student characteristic, might vary the approach that learners adopt. For instance, Beattie et al. (1997) claimed that factors such as the learners’ attitudes of the lecturer, perception of the relevance of the learning task, and the expected forms of assessment, might all lead to specific learning situations, which could modify their approach to learning.

Entwistle (1987) and Biggs (1987) extended the definitions of deep and surface categories to suggest a third approach, strategic or achieving approach. This approach is related to the students’ intentions of learning for ego-enhancement or for excelling through organized activities, such as appropriate use of study skills and cue-seeking behavior. Unlike the surface and deep approach learners, strategic learners focus more on effective organization, time management, and self-regulation in study (Spencer 2003).

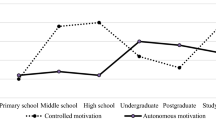

Marton (1983) and Biggs (1987) elaborated the relationships between motivational orientations and learning approaches by claiming that in essence, the deep approaches are based on intrinsic motivation and interest in the content of the task. Learners adopting the deep approach tend to focus on understanding the meaning of the learning material and attempt to relate new ideas to previous knowledge or concepts to everyday experiences. On the other hand, the surface approaches are seen as congruent with being extrinsic or instrumentally motivated. Biggs (1987, p. 21) concluded by claiming that students would “adopt the strategy most appropriate to their own complex of motives.”

Since cram schools are different from formal school learning context, students who learn English there may have any or all of the above-mentioned motives to any extent. The complex of motives may lead to their adoption of various learning approaches. Through investigating the motivational orientations, learning approaches, and the relationships between these, our understanding of English learners in the specific learning context, cram schools, would be advanced considerably.

Examination-Driven English Learning Environment

Attending cram schools has been a trend in East Asia, including Taiwan, and the number of students who attend cram schools has grown larger (Kwok 2004). This is mainly because apart from the integrity of teaching contents, teachers in cram schools would teach students a variety of questions and problem-solving strategies. It is generally believed that the teaching method in cram schools helps to considerably shorten the time of solving exam questions. This belief fosters the popularity of cram schools among Taiwanese senior high school students whose urgent need is to obtain satisfactory results at CEE.

Traditionally, English teaching at a senior high school consists of lecturing by teachers and note taking by students. Since repetition is believed by many to be the best way to accomplish learning tasks, learning by rote, drills, and constant tests are the most common methods used for teaching English in Taiwan. The instruction and learning in senior high schools are both exam-oriented with passing CEE as the ultimate goal (Chung and Huang 2009).

The context of learning is an important determinant of motivation and learning approach. There has been a large body of research relating to students’ motivational orientations and learning approaches in the school setting, yet few attempts have been made to penetrate cram school students’ motivational orientations and English learning approaches in the particular context of educational institution in Taiwan.

In view of this, the study sought to answer the following questions:

-

1.

What are cram school students’ motivational orientations in attending cram schools?

-

2.

What learning approaches do cram school students adopt in learning English?

-

3.

To what extent do cram schools facilitate students’ English learning?

Research Method

Instruments

The research study employed a combination of quantitative and qualitative data aggregation procedure. In the first phase of the study, data were collected through questionnaire survey conducted at 6 different cram schools located in the northern, central, and southern parts of Taiwan.

Based on the data and findings gathered from the questionnaires, interview questions were formulated for the second phase of the study. After the completion of the questionnaire survey, 24 respondents were invited from 4 of these cram schools to join the followup focus group interviews. These four focus group interviews provide useful individual opinions, and the in-depth data help clarify and further understanding of students’ motivation for attending a cram school and the approach they adopt to learn English in that specific context.

Participants

Cluster sampling was used in this study, in which the sample members were recruited from different cram schools and classes. Cluster sampling enabled the researcher to obtain a list of clusters more easily and to gather results within less time. A total of 365 participants were selected randomly from 6 different cram schools in the northern, central, and southern parts of Taiwan to respond to the questionnaire. The sample consisted of 172 (47.12 %) male students and 193 (52.88 %) female students. Only students in their final year of senior high school were selected because they were expected to provide more comments on their experiences at cram school. Being in the final year of senior high school, they share the same goal of obtaining satisfactory academic results in the upcoming CEE in order to get admission to an ideal university.

From a cram school in northern Taiwan, 6 students were selected to join the focus group interview conducted there. Another focus group interview took place in central Taiwan after a successful recruitment of 6 interviewees from a cram school located there. Finally two other interviews were conducted in southern Taiwan, each interview with 6 interviewees from two different cram schools in the south. All the interviewees were selected through the recommendation of their tutor, who helped to insure the focus group members were as heterogeneous as possible.

Data Analysis

Microsoft word and Excel software were used to compute the questionnaire data, and the frequency and percentage of students’ responses were displayed. All the focus group interviews were tape recorded so the process of data analysis was mainly tape based. Relying on listening to the tape recording, an abridged transcript of the relevant and useful part of the discussion was developed. The researcher focused mainly on the key ideas and main themes arising through the discussions. Simple analytic induction was then adopted to generate descriptive and qualitative data. Each subsequent group was analyzed and compared to earlier groups (Krueger and Casey 2000).

Results

Motivational Orientations in Attending Cram Schools

Table 1 summarizes some of the key findings of students’ motivational orientations in learning English at cram school.

As the table revealed, 84.11 % (307) of the respondents agreed that attending cram schools was of their own will. Some interviewees claimed that they chose to attend a cram school because they worried that they would fall behind others if they did not do so. As one interviewee maintained, “I believe cram schools can help to promote my English exam results. I feel anxious if I am unable to catch up with others who attend cram schools.”

Responses from 342 (93.70 %) of these respondents showed that “getting admission to an ideal university” was a key factor that prompted them to go to cram schools. Similar results were obtained from the focus group interviews, in which a majority of interviewees expressed that they hoped learning English in cram school helped them perform well in exams and gain admission to university. As one interviewee reflected, “My elder sister went to a cram school before being admitted to a good national university. I was very much inspired by her, so I set the goal for myself to attend a good university. I just don’t want to let my parents down.” Most were convinced that a university diploma was essential for them to find a decent job in the future. Some also pointed out that learning English might enhance their job opportunities. As can be seen, instrumental motivation seems to play a key role in students’ current learning context of cram schools.

Integrative motivation was the second major motivation revealed from the research data. A fairly high percentage, 87.12 % (318), of respondents indicated that they attended cram schools in the hope that their English proficiency could be enhanced, particularly the ability of oral communication. When asked about their motivation in learning English, a high percentage, 81.37 % (297), of respondents showed desire to learn English in order to know more about the “western culture” and to communicate with “foreigners.” As an interviewee expressed, “English is not merely a required subject for passing CEE. I want to enhance my English ability and broaden my vision.” However, only 63 (17.26 %) of the questionnaire respondents felt that the cram schools they attended placed emphasis on promoting their English communicative ability or on advancing their knowledge of the “western culture.”

Learning Approaches at Cram Schools and Learning Results

Table 2 reports on the key questionnaire findings of students’ English learning approaches at cram school.

The data gathered from both the questionnaires and focus group interviews indicated that English teaching at cram schools was mostly teacher centered with little interaction between students and tutors. The analysis of grammar, practice on sentence patterns, and sharpening exam-taking skills were reported to be the main focus in an English class. A high percentage 80 % (292) of the questionnaire respondents and many interviewees did not think this type of instruction motivated them to learn English. One of the interviewees claimed, “Most of the time, the tutors teach to the test or repetitively review past lessons, which was really exhausting.”

Other findings also reflect characteristics of the surface approach. For example, data reveal that cram school teachers’ major task was to follow routine procedures and transmit knowledge of the academic subject to learners. 342 (93.69 %) of the questionnaire respondents pointed out that they were expected to memorize and reproduce the contents they learned through repeated drills. As one interviewee maintained, “To be honest, I have adapted my English learning approach to suit the assessment structure of CEE. I hope this temporary suffering will at least help me get through the exam.” Among the respondents, 308 (84.38 %) revealed that they did not like to learn English in this way. Another interviewee added, “I like English, but I am not happy with the way we are taught to learn English here. I hope I won’t have to learn English this way after attending university.”

Participants’ accounts showed that cram school teachers played a dominant role while students adopted a passive role in an English class. Cram school students’ learning approaches were chiefly guided by teachers’ ways of teaching. However they disliked it, a majority of focus group interviewees agreed that rote learning, which relied heavily on memorization, was a fairly useful and efficient way to obtain high sores within a limited period of time. Nevertheless, this finding is not so much consistent with the literature suggestion that “a surface approach is associated with less examination success while a deep approach is associated with more successful academic performance (Spencer 2003).” This finding may be attributed to other influential factors such as learners’ strong instrumental motivation and the strategic approach they adopted.

In addition to the surface approach, data revealed that strategic approach was also crucial among cram school students in learning English. As high as 89.32 % (326) of the questionnaire respondents indicated that cram school English teachers were good at teaching them the problem-solving skills. Many interviewees claimed that they were often instructed to find clues to answer exam questions for various subjects, including English. Moreover, they were reminded of the importance of time management and self-regulation in study from time to time at cram school. This may account for the reason why a majority of participants (80 %) thought since attending a cram school, they have learned to focus more on managing study time, regulate themselves, and be more effective in learning. A number of interviewees admitted that both peer pressure and their own will to pursue breakthrough motivated them to excel themselves and others. One interviewee expressed, “From my cram school, I learn to be more disciplined and organized in studying English. Keen competition there also makes me want to improve and even surpass myself.” Obviously, attending cram schools had helped many participants transform and become more strategic learners of English.

An important aspect of evaluating the effects of English learning concerns learners’ competence in using English. Among the questionnaire respondents, 72.60 % (265) found attending cram school to be beneficial in terms of getting better grades in English tests and exams at school. Only 18.63 % (68) did not think cram schools helped enhance their tests or exam results. Nevertheless, a high percentage (76.99 %) of the respondents indicated that they still did not have much confidence in using English after learning it at cram school. Only 20.27 % (74) of the participants agreed that their competence in using English had improved since they attended cram school.

It is noteworthy that 82.74 % of the questionnaire respondents did not think high scores in English means “high level of English proficiency.” Similarly, a large number of focus group interviewees did not equate high scores with high English proficiency. They generally believed that people who were proficient in English were able to communicate in English competently and confidently. As one interviewees confessed, “I feel my exam-taking techniques are enhanced after attending a cram school, where we learn skills or techniques on answering exam questions most of the time. However, I still don’t have much confidence in my English proficiency, particularly in the aspects of listening and speaking.” Another interviewee added, “My exam scores are improving, but I’m not sure if this means my English has really become better. I would say my English is good only when I become competent in using English, such as being able to talk to foreigners in English fluently.”

Discussion and Implications

Although the sample in the study may not represent the large number of students in the cram schools throughout Taiwan, the research study provides a range of understandings of English learning in the special educational context, cram schools in Taiwan. The findings also offer a number of implications for English teachers and education reformers.

One finding emerged from this study is that instrumental motivation played a dominant role in why students chose to attend cram school. Achieving good exam results to gain admission to an ideal university motivated students to attend a cram school. Cram schooling was seen as helpful in achieving their short-term goal of getting admitted to an ideal university. Students learned English at cram schools for utilitarian benefits since many associated a university diploma with promising career development.

The participants’ motivation for learning English as a long-term aim, nevertheless, was quite different from that for learning English in cram school. Data gathered from both questionnaires and interviews demonstrated that integrative motivation were important in encouraging cram school students to learn English. Participants expressed their desire to master English to communicate with people from English-speaking countries or to know more about them. Interestingly, most equated “good English” with being able to communicate in English competently and confidently.

More complex of motives may exist in learning English among cram school students. Based on their strongest motive at the current learning stage, students adopted the most appropriate and effective learning approach to suit the perceived context of a subject area. Their English learning approach reflects many characteristics of the surface approach. Since achieving good exam results in English was a task they had to complete in order to gain admission to university under the current assessment policy of CEE, learning English was viewed mostly as a means to an end. This may explain why even learners who liked learning English did not enjoy their current task or learning approach. Non-reflective teaching practices, excessive loads, and one right answer scenarios on CEE may all reinforce surface learning among cram school students. This finding supports the contention that the surface approaches are congruent with being extrinsic or instrumentally motivated (Marton 1983; Biggs 1987).

From the results, it is noticeable that despite the positive association demonstrated in literature between a surface approach and lower academic performance (Biggs 1987; Byrne et al. 2002; Davidson 2002), participants who were found to adopt mainly the surface approach believed this approach was beneficial in helping them achieve good exam results. A reason for explanation is probably because strategic approach, which was claimed to be positively associated with high academic performance (Byrne et al. 2002), was also found crucial in how cram school students approach English learning. Without doubt, learners’ motivation in attending a cram school would also be an effective factor in influencing their academic performance.

This finding further implies the complexity of the learning context of cram schools, where achieving good exam results outweighs other learning tasks. Biggs (1987, p. 21) claimed that learners’ motivational mix might change not only from subject area to subject area and from time to time. It is evident from the finding that learners’ motivation orientation in learning English varied from time to time, which, accordingly, led to the adoption of different learning approaches. Their perception of assessment and expected form of assessment (CEE) further modified the way they approached English learning. The finding that students adapted their learning approach to suit the assessment structure echoes the argument by Entwistle and Ramsden (1982) that assessment is probably the most important contextual variable that affects learning approach.

The participants were aware that cram schooling could not successfully boost their English proficiency or confidence in using English. Realizing the fact that good exam results were not equal to competence in using English in the authentic context, they showed strong intentions of developing English communicative ability in the long run. Unfortunately, cram schooling was unable to provide sufficient skills or strategies to help learners meet their long-term needs. Neither could CEE reflect the other facet of students’ motivational orientation. Just like in senior high schools, English instruction and learning in cram schools are very exam-oriented. Before CEE can successfully evaluate what students believe to be “good English ability,” the stakeholders should reconsider and reexamine the way that CEE evaluates our English learners.

Svensson’s (1977) study revealed that the process of learning affects learning outcomes and that the method learners use to acquire knowledge is critical to their ability to “use” that knowledge. He argued that learners who adopt surface approach to acquire knowledge tend to memorize facts that are contained in structures, which cannot be easily applied to other contexts. Svensson’s contention can be supported by the present study, in which a majority of participants found themselves failed to successfully transfer the knowledge they gained in an English class to the actual “use” in the real communication context. To be able to apply their knowledge of English in memory to contexts other than CEE, learners should be encouraged to adopt not only the surface but also the deep approach.

In order to better reflect learners’ needs, a more multiple evaluation method should be introduced to evaluate students’ basic communication ability in English. Assessment which would require or encourage a deep approach in learning English can be designed. This change would be mirrored in alterations to English instruction and learning in not only cram schools but also the context of general high schools. In this way, CEE can not only function in selecting students but also better meet students’ long-term need in promoting English proficiency.

English learners’ low confidence in English communicative ability may be attributed to lack of authentic environment. English teachers in various teaching contexts are suggested to help by creating a near-authentic environment to enhance students’ opportunities as well as proficiency in English communication. When learners who are aware of their own deficiency in the ability to communicate in English perceive the relevance of the learning task, their intrinsic interest and enthusiasm in learning English might be promoted considerably.

Conclusions

The existence of cram schools has been regarded as a barrier and challenge in the recent governmental education reform in Taiwan. The steep growth and sustained popularity of cram schools that follow the reform, however, indicate the failure of government’s attempt to reduce senior high school students’ academic pressure or dependence on cram schools. Nowadays senior high school students are still overloaded with heavy demands of various school subjects.

The intent of this study is not to make judgment of whether CEE or cram schools should continue to exist. From studying students’ motivational orientations of attending cram schools and their approach in learning English, the researcher revealed the complexity of the multi-faceted relationships between students’ motivation and English learning approach. In spite of the widespread criticism of the teacher-led or teacher-centered instruction of cram schools, the deep-rooted cram schooling culture is not going to end soon as long as the examination-oriented learning culture continues to exist.

Findings of this study advance our recognition of cram school students’ motivation for learning English. Attending university seems to be an urgent and the uppermost learning aim in their current stage of English learning. It is inspiring, however, to find that a considerably large number of students were also interested in promoting their confidence in using English, particularly the ability to communicate in English fluently, as well as in knowing more about the culture or people of the English-speaking countries.

While educational reformers endeavor to make or implement a new policy, they should take into consideration students’ needs and motivation. After all, students should be the main subjects in the process of policy making. Although the sample in the present study may not be representative of the large number of English learners at cram schools in Taiwan, the results may provide a useful indicator for the government, educators and related stakeholders in considering how to promote students’ English learning motivation and effectiveness.

Students need a more holistic learning environment so they can be fully developed to cope with the fast changing society. Since high school education is chiefly directed by CEE, change could involve designing assessment items that encourage deep learning. Besides, it is worth considering what we can offer to help meet English learners’ long-term needs, rather than just to achieve their short-term goal of passing exams. Most importantly, this study is an attempt to inspire reconsideration among English teachers, educational reformers, or even parents of how we can better assist our new generation in learning English and prepare them for the increasingly challenging world.

References

Beattie, V., Collins, B., & McInnes, B. (1997). Deep and surface learning: A simple or simplistic dichotomy? Accounting Education, 6(1), 1–12.

Biggs, J. B. (1987). Student approaches to learning and studying. Hawthorn: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Biggs, J. B. (1993). What do inventories of students’ learning processes really measure? A theoretical review and clarification. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 63, 3–19.

Biggs, J. B., & Moore, P. (1993). The process of learning (3rd ed.). New York: Prentice Hall.

Byrne, M., Flood, B., & Willis, P. (2002). The relationship between learning approaches and learning outcomes: A study of Irish accounting students. Accounting Education, 11(1), 27–42.

Chung, I. F., & Huang, Y. C. (2009). The implementation of communicative language teaching: An investigation of students’ viewpoints. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 18(1), 67–78.

Dart, B., Pillay, H., & Burnett, P. C. (2000). Australian and Filipino students’ approaches to learning, conceptions of learning, and learner self-concepts: A cross cultural comparison. Educational Research Journal, 15, 143–166.

Davidson, R. A. (2002). Relationship of study approach and exam performance. Journal of Accounting Education, 20, 29–44.

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Teaching and researching motivation. Essex: Longman.

Entwistle, N. J. (1987). A model of the teaching-learning process. In J. T. E. Richardson, M. W. Eyesenck, & D. W. Piper (Eds.), Student learning: research in education and cognitive psychology (pp. 13–28). London: S.R.H.E./Open University Press.

Entwistle, N. J., & Ramsden, P. (1982). Understanding student learning. New York: Croom Helm.

Gardner, R. C., & Gilksman, L. (1982). On “Gardner on affect”: A discussion of validity as it relates to the attitude/motivation test battery: A response from Gardner. Language Learning, 32(1), 191–200.

Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second language learning. Rowley: Newbury House.

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation. London: Edward Arnold.

Gardner, R. C., & MacIntyre, P. D. (1991). An instrumental motivation in language study. Who says it isn’t effective? Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 13(1), 57–72.

Gibbs, G. (1992). Improving the quality of student learning. Bristol: Technical and Educational Services Ltd.

Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2000). Focus Groups: A practical guide for applied research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Kwok, P. (2004). Examination-oriented knowledge and value transformation in East Asian cram schools. Asia Pacific Education Review, 5(1), 64–75.

Lambert, W. E. (1974). Culture and language as factors in learning and education. In F. E. Aboud & R. D. Meade (Eds.), Cultural factors in learning and education (pp. 91–122). Proceedings of the Fifth Western Washington Symposium on Learning. Bellingham: Western Washington State College.

Li, J. (2003). U.S. and Chinese cultural beliefs about learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(2), 258–267.

Lin, D. S., & Chen, Y. F. (2006). Cram school attendance and College Entrance Exam scores of senior high school students in Taiwan [in Chinese]. Bulletin of Educational Research, 52(4), 35–70.

Linnenbrink, E. A., & Pintrich, P. R. (2002). Motivation as an enabler for academic success. School Psychology Review, 31(3), 313–327.

Marton, F. (1983). Beyond individual differences. Educational Psychology, 3, 289–303.

Ministry of Education, Taiwan. (2002). Survey on learning and life of elementary and high school students in Taiwan [in Chinese]. http://www.edu.tw/statistics/content.aspx?site_content_sn=7867. Retrieved Aug 22, 2011.

Ministry of Education, Taiwan. (2011). Cram school information system [in Chinese]. http://bsb.edu.tw. Retrieved Jan 12, 2012.

Prosser, M., & Trigwell, K. (1999). Understanding teaching and learning: The experience in higher education. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Saville-Troike, M. (2006). Introducing second language acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Spencer, K. (2003). Approaches to learning and contemporary accounting education. Education in a changing environment 17th–18th conference proceedings. Salford: University of Salford.

Svensson, L. (1977). Symposium: Learning processes and strategies–III on qualitative differences in learning: III–study skill and learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 47(3), 233–243.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chung, IF. Crammed to Learn English: What are Learners’ Motivation and Approach?. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 22, 585–592 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0061-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0061-5