Abstract

This study aimed to determine what types of ethical climates are perceived by 256 faculty members who worked in Hashemite University-Jordan, using the Ethical Climate Questionnaire. The results revealed that perceived organizational ethical climate in order were egoistic (M = 4.29, SD = .48), utilitarian (M = 3.45, SD = .51), and deontological (M = 3.04, SD = .53). There were no significant differences among faculty members regarding their gender and academic rank. The researcher recommended that future research should be conducted on the types of ethical climates in different universities and different variables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Throughout the past decade, the increasing lack of ethical behavior in the workplace has manifested itself as creation of challenging ethical climates, stimulating the research on ethics in organizations. The literature addressing ethical behavior in organizations has varied in approaches ranging from the establishment of ethical codes (Marnburg 2000; Moore 2006; Trevino and Weaver 2003) to creating teachable lessons on workplace ethics (Falkenberg and Woiceshyn 2008; Jurkiewicz et al. 2004; Shaw 2008; Trevino and Nelson 2007).

Ethical climates are best understood as a group of prescriptive climates reflecting the organizational procedures, policies, and practices which lead to moral consequences (Victor and Cullen 1988). Universities are not exempt from ethical dilemmas, either. According to Kelley and Chang (2007), universities that have not experienced major ethical scandals tend to neglect the need for an established ethical culture and the need for promoting ethical initiatives. The ethical climates of non-profit organizations including colleges and universities are being scrutinized for how they are addressing ethical dilemmas, such as questionable accounting practices with public resources (Campbell 1995), as well as selection and retention of university presidents (Grunewald 2008).

Felicio and Pieniadz (1999) found that there is a lack of systematic forums and frameworks for attempting to resolve ethical dilemmas in higher education. One of the few approaches to addressing ethical dilemmas in organizations is the use of codes of ethics. Despite established codes of ethics, the need for enforcing policies on ethical decision making is often overlooked until something undesirable happens. Marnburg (2000) tested the differences in ethical attitudes among employees in companies with and without a code of ethics. The study found that there is no significant difference, exhibiting that members of many organizations that have ethical codes still exhibit unethical behaviors.

In terms of the higher education institution, Moore (2006) proposed that an institution-wide ethical policy framework beyond the traditional focus on an ethical code and policy is required to embrace all of the institution’s activities. In Schein’s (2004) work on organizational culture, he found that institutional factors such as the environment, organizational culture, and leadership have the potential to be as important, if not more important, in determining the ethical climate. A positive relationship between the organization and its environment is established when organizations systematically align their major organizational components (such as structure, technology, systems, people, and culture), with the external environment (Fiol and Lyles 1985).

Ethical Climate Theory

Ethical climate theory (ECT) developed by Victor and Cullen (1988) is being used to support this study for its ability to effectively capture the complex relationships that exist between levels of analysis (individual perceptions, organizational structures, and external societal factors) and provides an efficient theoretical frame from which to measure ethical climate perceptions. ECT represents a descriptive map of the ethical decisions and actions that shape the ethical climate within an organization (Martin and Cullen 2006).

The philosophical approaches used within ECT are the guidelines by which ethical decisions are framed (Martin and Cullen 2006). Each construct is based in philosophical underpinnings of ethics; Egoism, benevolence (utilitarianism), and principle (deontology) dimensions. The first construct, egoism, applies to behaviors that are concerned first and foremost with self-interest and self-interest maximizing behavior. The two other constructs are not as focused on the individual and are instead concerned with the well-being of others. Utilitarianism applies to the basis of decisions and actions that arrive at the greatest good outcome for the greatest number of people. The third construct, deontology, classifies the behaviors that are guided by principle, rules, law, codes, and procedures, which specify decisions and actions for the good of others.

Egoism

Ethical egoism posits that it is an individual’s moral obligation to do what promotes his own good or welfare (Kagan 1998). Egoism is primarily based upon “the maximization of self-interest” (Martin and Cullen, 2006; Cullen et al. 2003). The initiative to make the decision comes directly from the individual, ignoring the needs or the interests of others. Within the egoistic climate the prevailing interests of the individual has the capacity to dictate the course of action the organization may take. The egoistic ethical climate implies that employees perceive that the organization generally promotes self-interested decisions at the expense of other stakeholders.

In a 2003 study, Cullen et al. found that egoistical ethical climates are negatively related to organizational commitment. “If individuals perceive an egoistic or self-interested climate, they believe they are encouraged by the organization to promote their own self-interest and probably also view other employees as self-interested (p.12).” Employees may feel that it is “in their best interest” to reward themselves for their hard work by taking an extra hour at lunch time, or skimming a few dollars off the top of a budget line item for their compensation. Egoistic climates are less likely to form cohesive groups, another antecedent Cullen et al. found to organizational commitment.

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism focuses on bringing the greatest amount of good to the greatest number of individuals (Donaldson and Dunfee 1994). The decision-maker seeks the alternative that maximizes all of the interests involved, even if it means a lesser satisfaction for a particular individual’s needs (Cullen et al. 2003). Those organizational members of the utilitarian ethical perspective see their organization as having a vested interest in the well-being of others.

The Utilitarian climate, carries the expectation that each organizational member is concerned with the well-being of each other internal and external to the organization (Victor and Cullen 1988). Common characteristics of professionals within the utilitarian climate are cooperation, mutual respect, and positive feelings about tasks. As the communitarian aspects of utilitarianism are instilled in the organizational climate, so is the support for group cohesiveness among organizational members. In their 2003 study, Cullen et al. found that organizational commitment is positively related to utilitarian ethical climates.

Deontology

Within the deontological ethical climate perspective, there are set principles by which policy, procedures, and behaviors are managed. A common approach to deontological ethics in business is the development of a code of ethics (Weber 1993). Historically, ethical codes: (1) were originally referred to as creeds or credos, more recently referred to as written documents which attempt to state major philosophical principles and articulate values embraced by the organization. (2) Articulate ethical parameters of organizations. (3) Policy documents defining responsibilities of the organization to stakeholders and articulate conduct expectation of employees. (4) Instruments to enhance social responsibility, and clarify norms and values organizations seeks to uphold. (Stevens 2008).

In examining previous research, the researcher found no study related to Jordanian faculty members, specifically among faculty’s at the Hashemite University investigating organizational ethical climate. For example, one of the studies done by Al-Omari et al. (2009) investigated evaluating the faculty members’ satisfaction’s (270 faculty members) on the campus climate at academic and applied universities in Jordan as perceived by faculty members. The study concludes that evaluation of campus climate at academic and applied universities as perceived by faculty members is, in general, medium with (Mean = 2.47 of 5.00). Therefore, there is a need for additional research on the organization’s ethical climate in the Hashemite University.

Statement of the Problem

Universities are not immune to the issues of organizational ethical distress and failure. With increasingly tight economic times and the regulation of new governmental policies, educational institutions and other governmental agencies are under intense scrutiny by citizenry (Grunewald 2008; Campbell 1995). The ethics of organizations is often held accountable to the public to the degree that they paternalistically change skills, attitudes, and behaviors of individuals for the predetermined individual’s good or the public’s good or both.

The greater diversity in audience served is likely to result in a wider range, and possibly conflicting sets of values and ethical assumptions regarding the utility of public institutions (Iverson 2008). Although despite those highlighted in the literature there are limited studies on ethical climates in Jordanian universities. Due to the lack of empirical support for the overarching context of this study, the present study is an exploratory examination of how ethical climates are perceived by faculty members in Jordanian universities.

Purpose and Questions of Study

A survey of the related literature in Jordan indicated paucity of research that addressed the organization’s ethical climate in Jordanian universities. Therefore, the purposes of the study are to determine specific elements of the organization’s ethical climate and analyze the significant differences in universities faculty members based in their gender and academic rank.

This study addressed the following specific questions:

- Question 1::

-

How do faculty members perceive organizational ethical climate in Jordanian universities?

- Question 2::

-

Do organizational ethical climate as perceived by faculty members differ based on their gender and academic rank?

Significance of the Study

The results of this exploratory study have multiple implications for Higher Education Institutions. The results of this study will provide empirical data examining the perceived ethical climates and potentially use results to support the development of training programs, professional development opportunities, and effective assessments of ethical climates within the university. To help shape the university’s climate through understanding and appreciating the growing emphasis on ethics in professional organizations, higher education, and by shaping ethical corporations through training and development. More importantly, can help ethics education become an essential element of organizational learning.

Research Methodology

Research Design

This study was a quantitative study conducted through utilizing the Ethical Climate Survey research instrument to assess faculty members’ perception of the organization’s ethical climate among universities in Jordan.

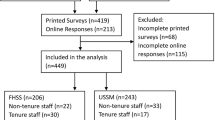

Population and Sample of Study

The population involved with this study consists of the faculty members who worked in the Hashemite University in Jordan. This university utilizes 586 faculty members. In gathering data from a random sample of these faculty members, various faculties were selected in a random manner and the leader of each faculty was contacted to coordinate administering the instrument. Data collection continued from randomly selected faculties until data had been obtained from at least the minimum number of respondents from the faculty members. In conducting the study, the actual response rate for faculty members collected was only 256 valid responses.

Instrumentation and Measurement

Ethical Climate Questionnaire

A 24 items from Victor and Cullen’s (1988) Ethical climate questionnaire (ECQ) were used; the ECQ emphasizes the description of, rather than feelings about, the work setting. The instrument places emphasis on the observers reporting of the perceived ethical climate rather that an evaluation of the climate.

The ECQ is a series of twenty-four items, with items assigned for each ethical climate; egoistic, utilitarian, and deontological. Within each of the climates, the ECQ measures perceptions from the individual, local (organizational), and cosmopolitan (societal) level. Through the use of a Likert-scale format, the instrument is designed to elicit the perceived ethical climate within the subject’s organization. Participants rate how valid a statement is regarding their organization, using the ratings: “Strongly Disagree” = 1, “Disagree” = 2, “Neutral” = 3, “Agree” = 4, “Strongly Agree” = 5.

The use of Victor and Cullen’s ECQ has been wide spread over the past two decades. Studies have examined variables such as elements of organizational design (Weber 1993), employees’ attitudes and behaviors (Trevino et al. 1998), organizational commitment and innovation (Cullen et al. 2003; Ruppel and Harrington 2000), and ethical leadership (Forte 2004).

For the purpose of examining the validity of the instrument (face validity evidence) it was presented to post-secondary education experts. They were asked to check whether the statements in the instrument are clear and linked appropriately with the dimensions that were classified to them in advance.

Regarding the reliability of the instrument test–retest procedure was used; a pilot study had been conducted. 30 faculty members participated in the pilot study, those faculty members did not participate in the final study. Stability coefficients for the instrument in each case were 0.87, 0.89, and 0.81 for the first, second, and third dimensions, respectively. These values can be considered reasonably satisfactory to support the objectives of the current study. For Victor and Cullen’s Ethical Climate Questionnaire, Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.72 to 0.91 (Cullen et al. 2003; Trevino et al. 1998; Cullen et al. 1993; Victor and Cullen 1988; Weber 1993).

Data Collection and Analysis

Faculty members were visited at their offices to complete the ECQ research instrument. The average time to complete the ECQ was 15 min. The quantitative data was then entered into the SPSS computer program to assist in the analysis of the data.

Using SPSS version 17 for Windows, several steps were involved in analyzing the data provided by the participants. The first step involved the scoring of the ECQ to attain sub-scores for Ethical climate. Sub-scores were derived by summing the items for each scale and dividing by the number of items that make up each scale. Each of the questions is based on a five-point Likert-scale, with a response of strongly disagree being given one point and a response of strongly agree given a point of five points.

Results

Question 1: How do Faculty Members Perceive Organizational Ethical Climate in Jordanian Universities?

The perceived organizational ethical climate in Jordanian universities by faculty members in order were egoistic (M = 4.29, SD = .48), utilitarian (M = 3.45, SD = .51), and deontological (M = 3.04, SD = .53) as presented in Table 1.

Question 2: Do Organizational Ethical Climate as Perceived by Faculty Members Differ Based on Their Gender and Academic Rank?

t test were used to examine the difference in means between male and female faculty member’s ethical climate perceived. Related to gender; Table 2 shows that there were no significant differences between male and female faculty members in the perceived ethical climate.

Related to faculty members academic rank; utilizing three-way analysis of variance, Table 3 shows that there were no significant differences among the three groups of academic rank (professor, associate, and assistant) in faculty members in organizational ethical climate.

Discussion

With current societal trends such as economic distress and continual ethical dilemmas, examining potential strategies for supporting positive ethical climates is more essential than ever. In organizations such universities, there is greater potential for ethical dilemmas (Blewett et al. 2008; Holland 2001; Iverson 2008).

The ECQ measured three individual ethical climates; the egoistic, the deontological, and the utilitarian. Of the three ethical climates, participants identified the Egoistic climate with mean score (M = 4.29) as the most prevalent climate than others—utilitarian (M = 3.45) and deontological (M = 3.04). Within the framework of egoistic ethical climates, ethical decisions comes directly from the individual, ignoring the needs or the interests of others (Victor and Cullen 1988). Egoism is primarily based upon “the maximization of self-interest” (Martin and Cullen 2006; Cullen et al. 2003). The egoistic ethical climate implies that employees perceive that the organization generally promotes self-interested decisions at the expense of other stakeholders.

Faculty members’ perceptions have the potential to be influenced by their self-interest; Cullen et al. (2003) revealed in their study that egoistical ethical climates are negatively related to organizational commitment. Anegoistic or self-interested climate perceived by employees will encourage them to promote their own self-interest and probably also view other employees as self-interested. Egoistic climates are less likely to form cohesive groups, another antecedent Cullen et al. found to organizational commitment.

Studies have shown that variables such as gender, age, and education level have both a significant (Parboteeah et al. 2008) and insignificant (Van Sandt 2001) effect on perceived types of ethical climates. Research results from this study showed that there are no significant relationships between the personal characteristics of gender and academic rank with perceived ethical climates.

Implications

Future research should be conducted on the types of ethical climates perceived in various universities, for public and private. Additional studies should include multiple levels of personnel from within university. The framework of this study should be replicated with universities staff perceptions. Further research should be conducted in an effort to better understand the benefits and challenges associated with a strong egoistic ethical climate. Further research is needed to examine what types of quality indicators are associated with egoistic ethical climates in universities. Future research involving ethical climate and personal characteristics of university employees should be done. Future research should consider other possible variables that may also affect individual’s perceived organizational ethical climate. For example, background of the study, expertise, years in the field, etc. Furthermore, future research can consider conducting qualitative data to add value to quantitative data.

References

Al-Omari, A., Khasawneh, S., & Abu Tineh, A. (2009). Academic and applied campus climate as perceived by faculty members at Jordanian universities: Comparative study. Damascus University Journal, 25(3+4), 495–530.

Blewett, T. J., Keim, A., Leser, J., & Jones, L. (2008). Defining a transformation education model for the engaged university. Journal of Extension, 46(3), 1–4.

Campbell, J. R. (1995). Reclaiming a lost heritage: Land-grant and other higher education initiatives for the twenty-first century. Michigan State: Lansing.

Cullen, J. B., Parboteeah, K. P., & Victor, B. (2003). The effects of ethical climates on organizational commitment: A two-study analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 00, 1–15.

Cullen, J. B., Victor, B., & Bronson, J. W. (1993). The ethical climate questionnaire: An assessment of its development and validity. Psychological Reports, 73, 667–674.

Donaldson, T., & Dunfee, T. W. (1994). Toward a unified conception of business ethics: Integrative social contracts theory. Academy of Management Review, 19(2), 252–284.

Falkenberg, L., & Woiceshyn, J. (2008). Enhancing business ethics: Using cases to teach moral reasoning. Journal of Business Ethics, 79, 213–217.

Felicio, D. M., & Pieniadz, J. (1999). Ethics in higher education: Red flags and grey areas. Feminism and Psychology, 9(1), 53–73.

Fiol, C. M., & Lyles, M. A. (1985). Organizational Learning. Academy of Management Review, 10(4), 803–813.

Forte, A. (2004). Business Ethics: A study of the moral reasoning of selected business managers and the influence of organizational ethical climate. Journal of Business Ethics, 51, 167–173.

Grunewald, D. (2008). The Sarbanes-Oxley Act will change the governance of non-profit organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 80, 399–401.

Holland, B. (2001, March). Exploring the challenge of documenting and measuring civic engagement endeavors of colleges and universities. Paper presented at the Campus Compact Advanced Institute on Classifications for Civic Engagement. http://www.compact.org/advacedtoolkit/measuring.html. Accessed 15 Sep 2010.

Iverson, S. V. (2008). Now is the time for change: Reframing diversity planning at Land- Grant Universities. Journal of Extension, 46(1), 1–11.

Jurkiewicz, C. L., Giacalone, R. A., & Knouse, S. B. (2004). Transforming personal experience into a pedagogical tool: Ethical complaints. Journal of Business Ethics, 53, 283–295.

Kagan, S. (1998). Normative ethics. Boulder: Westview.

Kelley, P. C., & Chang, P. L. (2007). A typology of university ethical lapses: Types, levels of seriousness, and originating location. The Journal of Higher Education, 79(4), 402–429.

Marnburg, E. (2000). The behavioral effects of corporate ethical codes: Empirical findings and discussion. Business Ethics: A European Review, 9(3), 200–210.

Martin, K. D., & Cullen, J. B. (2006). Continuities and extensions of ethical climate theory: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Business Ethics, 69, 175–194.

Moore, G. (2006). Managing ethics in higher education: Implementing a code or embedding virtue? Business Ethics: A European Review, 15(4), 407–418.

Parboteeah, K. P., Hoegl, M., & Cullen, J. B. (2008). Ethics and religion: An empirical test of a multidimensional model. Journal of Business Ethics, 80, 38–398.

Ruppel, C. P., & Harrington, S. J. (2000). The relationship of communication, ethical work climate, and trust to commitment and innovation. Journal of Business Ethics, 25, 313–328.

Schein, E. (2004). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Shaw, W. H. (2008). Marxism, business ethics, and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 84, 565–576.

Stevens, B. (2008). Corporate ethical codes: Effective instruments for affecting behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 78, 601–609.

Trevino, L. K., Butterfield, K. D., & McCabe, D. L. (1998). The ethical context in organizations: Influences on employee attitudes and behaviors. Business Ethics Quarterly, 8(3), 447–476.

Trevino, L. K., & Nelson, K. A. (2007). Managing business ethics: Straight talk about how to do it right (4th ed.). Hoboken: Wiley.

Trevino, L. K., & Weaver, G. R. (2003). Managing ethics in business organizations. Stanford: Stanford.

Van Sandt, C. (2001). An examination of the relationship between ethical work climate and moral awareness. Blacksburg: Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1988). The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33, 101–125.

Weber, J. (1993). Institutionalizing ethics into business organizations: A model and research agenda. Business Ethics Quarterly, 3(4), 419–436.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethical Climate Questionnaire

Ethical Climate Questionnaire

The following questions will ask you about the general climate of your university. Please indicate the extent to which you feel the following statements are true about your university

Items | Strongly agree 5 | Agree 4 | Neutral 3 | Disagree 2 | Strongly disagree 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

I-Egoistic | ||||||

1 | In this university, people are out for themselves | |||||

2 | People are expected to further the university’s interest | |||||

3 | There is no room for one’s own personal morals or ethics in this university | |||||

4 | Work is considered sub-standard only when it hurts the university’s interests | |||||

5 | In this university, people protect their own interest above other considerations | |||||

6 | People are concerned with the university’s interest | |||||

7 | Decisions are primarily viewed in terms of contribution to profit | |||||

8 | People in this university are very concerned about what is best for themselves | |||||

II- Deontological | ||||||

9 | It is very important to follow strictly the university’s rules and procedures here | |||||

10 | The first consideration is whether a decision violates any law | |||||

11 | People are expected to comply with the law and professional standards over and above other considerations | |||||

12 | Everyone is expected to stick by university rules and procedures | |||||

13 | Successful people in this university go by the book | |||||

14 | In this university, people are expected to strictly follow legal or professional standards | |||||

15 | Successful people in this university strictly obey the university policies | |||||

16 | In this university, the law or ethical code of theft profession is the major consideration | |||||

III- Utilitarian | ||||||

17 | In this university, people look out for each other’s good | |||||

18 | The most important concern in this university is each person’s sense of right and wrong | |||||

19 | In this university, our major concern is always what is best for the other person | |||||

20 | Our major consideration is what is best for everyone in this university | |||||

21 | It is expected that you will always do what is right for the students and public | |||||

22 | People are very concerned about what is generally best for employees in the university | |||||

23 | What is best for each individual is a primary concern for this university | |||||

24 | The effect of decisions on the students and the public are a primary concern in this university |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

AL-Omari, A.A. The Perceived Organizational Ethical Climate in Hashemite University. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 22, 273–279 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-012-0033-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-012-0033-1