Abstract

This study used a lesson unit of an academic subject to understand the quantity and quality of college students’ in-class and after-class lecture notes, and to explore the effects of note quantity and quality on academic performance. Thirty-eight freshmen students of a general psychology class in a university in southern Taiwan were recruited as participants. Their lecture notes and test scores on the lesson “Memory” were collected. The findings indicated that the quality of students’ lecture notes was poor. The quality level of in-class plus after-class notes was less than half the desired overall quality. In addition, both the in-class predictive model and in-class plus after-class predictive model could explain the variances of academic performance. In both models, the quality of in-class notes was the only significant predictor of academic performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Lectures continue to serve as the primary method for communicating course content to college students despite a host of innovations in instructional technology (Dyson 2008; Raver and Maydosz 2010; Titsworth and Kiewra 2004). For college students, note-taking is a pervasive strategy to aid in learning from lectures (Bonner and Holliday 2006; Van Meter et al. 1994). Although new technologies for note-taking have been developed (Kam et al. 2005; Morales 2004; Plaue et al. 2012), note-taking with paper and pen remains very popular in college classrooms. It has been argued that traditional note-taking will not be completely replaced by electronic learning technologies in the near future. An examination of college students’ lecture note-taking with paper and pen is indispensable for understanding and improving their school learning (Kobayashi 2006).

In academic settings, lectures are often planned for lesson units. Whether college students’ lecture note-taking for a lesson will enhance their learning performance concerning the lesson is an interesting question. Past studies discussing the effects of college students’ lecture note-taking on learning performance focused mainly on in-class note-taking in a single class session. It is noteworthy that a college lesson unit often takes a number of weeks or sessions to complete. In view of this, lecture note-taking for a lesson involves not only in-class but after-class note-taking as well (Kiewra 1997; Van Meter et al. 1994). There is little evidence attesting to the effects of after-class lecture note-taking on learning performance. This current study attempts to fill in the research gap by investigating both in-class and after-class lecture note-taking of college students, as well as exploring their effects on academic performance.

College Students’ Lecture Note-Taking and Academic Performance

A majority of college students said that they took notes in class and agreed that taking lecture notes is an effective way to improve academic performance (Castello and Monereo 2005; Palmatier and Bennett 1974). The benefits of note-taking are valued by teachers as well as students. A survey indicated that eighty-six percent of college teachers would like students to take notes in class as a means to assist their academic learning (Isaacs 1994). Recognized by teachers and students as an effective learning strategy, the relation between lecture note-taking and learning performance has also attracted the attention of researchers.

In the twentieth century behaviorism period, empirical studies began to discuss the question: Do note-taking students perform better than those who merely concentrated on listening in class? There was no consistent answer to the question until the 1970s when Di Vesta and Gray explored deeper into the functions of note-taking (Bonner and Holliday 2006). Di Vesta and Gray (1972, 1973) considered the actual role played by the note-taking strategy, specifically whether notes are more valuable as a method by which students can translate information into their understanding or as a source of information for later reference. In their studies, they found that taking lecture notes could help students encode the presented information and also that the notes taken in lectures would serve as an external storage for review. Hence, two functions of note taking, namely encoding and reviewing, were identified. Since then, a host of experimental studies have been conducted to test the functions of note-taking.

In studies discussing the encoding function, after-lecture test results of note-takers and non-note-takers were compared to see whether note-taking could help college students understand and memorize lecture content (e.g., Einstein et al. 1985; Peper and Mayer 1986; Weiland and Kingsbury 2001). In studies discussing the reviewing function, after-lecture test results of note-takers who reviewed the notes before the test and those who did not, were compared to determine whether reviewing could help college students recall lecture content (e.g., Carter and Van Matre 1975; Fisher and Harris 1973; Risch and Kiewra 1990). These studies basically agree that note-taking can help college students understand and memorize lecture content. Even if students do not review after lecture, taking notes alone can help to enhance their learning. Studies also agree that the notes, if saved in an exterior form, are helpful for future use. Reviewing notes helps college students to brush up on lecture content (Isaacs 1994; Van Meter et al. 1994).

Although experimental studies have recognized the effectiveness of taking and reviewing lecture notes, it does not mean that college students can improve academic performance simply by taking notes in class. In academic settings, it is found that many college students are not competent note-takers and often produce poor lecture notes. McDonald and Taylor (1980) studied the lecture notes of students studying veterinary medicine and found that the students did not draw diagrams and often missed important points of the lectures. Baker and Lombardi (1985) reviewed the lecture notes of students in a psychology class and found that a majority of students wrote down less than half of the important information needed for exams. As a matter of fact, a number of college students have weak note-taking skills (Cukras 2006; Raver and Maydosz 2010). These ineffective note-takers’ spontaneous note-taking procedures are defective in processing lecture information. Taking notes in class will not help them to encode the presented information, so they could not benefit much from the taking and reviewing of notes (Kiewra 1989; Kobayashi 2005).

For this reason, discussions on the effects of lecture note-taking on academic performance should not only focus on the difference between taking and not taking notes, or between reviewing and not reviewing; rather, the focus should be on the effects of note quantity and quality on academic performance. In a college class, Peverly et al. (2007) presented a videotaped lecture and told the students in advance that there would be a quiz afterward. Paper was distributed to the students for them to take notes. It was found that the regression model, which consisted of spelling, letter fluency, quality of notes, composition fluency, and verbal working memory, could explain the variances of test performance. In the model, quality of notes was the only significant predictor of test performance.

Previous studies concerning the effects of lecture note-taking on learning performance, experimental or correlational, primarily focused on short lectures in a single class session. In realistic academic settings, classes and exams are often planned for lesson units. A lesson unit might take several weeks or sessions to finish. It would be interesting to determine whether the quantity and quality of notes for a unit could help to predict unit test performance. In addition, in this situation, lecture note-taking includes not only “in-class” note-taking but “after-class” note-taking as well. As a matter of fact, quite a few researchers argued that lecture notes are usually completed after class, not in class. Students who want to make effective notes should record the points of lectures in class, and refine them by reading textbooks, searching relevant materials, and consulting teachers or classmates after class (Kiewra 1997; Pauk 1974; Van Meter et al. 1994). Nevertheless, little evidence is provided for evaluating after-class lecture note-taking. What lecture note-taking activities do college students participate in after class? What are the quantity and quality of after-class notes? Can after-class note quantity and quality help to predict academic performance as in-class ones do? All of these questions need to be explored further.

It is also noteworthy that there is little evidence on the lecture note-taking of Taiwanese college students. In Taiwan, despite innovative formats of teaching and learning (Shieh et al. 2010), lectures remain dominant in university timetables. Kuo (2011) examined the relationship between learning motivation and lecture note-taking among Taiwanese college students and found that learning motivation could positively predict the quantity and quality of lectures notes. Nevertheless, there is no evidence provided for the effects of Taiwanese college students’ lecture note-taking on academic performance. Investigating the issue has practical value for improving the academic learning of Taiwanese college students.

Purpose and Research Questions

In view of the aforesaid points, this study used a lesson unit of an academic subject to examine the quantity and quality of Taiwanese college students’ in-class and after-class lecture notes, and to explore the effects of note quantity and quality on academic performance. In order to realize how students took their lecture notes after class, students’ after-class lecture note-taking activities were also investigated. Specifically, the following questions were addressed:

-

1.

What are the quantity and quality of college students’ in-class and after-class lecture notes?

-

2.

Do the quantity and quality of in-class and after-class lecture notes predict academic performance?

-

3.

What lecture note-taking activities do college students partake in after class?

Method

Participants

The researcher recruited thirty-eight freshmen students (seven males and thirty-one females) taking a general psychology course in a Department of Educational Psychology and Counseling in a university in southern Taiwan.

Lecture and Notes

General Psychology is a required course in the freshmen year of the department. It is taught for one hundred minutes a week over two semesters, and is mainly lecture-based, with some class discussion. The course consisted of ten lesson units. Lectures and exams were planned for lesson units. The study targeted the sixth lesson unit, the 4 week lesson: “Memory”. The content of the lesson lecture was adapted from the eighth chapter of “Atkinson’s and Hilgards’ Introduction to Psychology” by Smith et al. (2009).

Before the lesson lecture, the teacher prepared twenty-seven slides for the lesson unit and gave the class printed handouts with three slide pages on the left and a column for taking notes on the right. The contents of the slides are shown in the “Appendix”; they were in skeleton form, with only simplified topics and subtopics. During the lesson lecture, the teacher presented slides in sequence via PowerPoint and lecture to the class on the main idea and supporting details for each topic or subtopic. The classroom for lecturing was not equipped with any computer for student use, nor did the students bring any Tablet PC to the class; this ensured that students would take notes with paper and pen without any technological aid.

This study collected two kinds of notes. The first kind was in-class notes that were taken during the 4 weeks of class. These were collected after each class and compiled after the unit was completed. The second kind was unit notes that were a combination of in-class notes and after-class notes. The unit notes were collected one time on the day of the unit test. Since the handouts had space for notes, most students took advantage of the handouts. The two kinds of notes collected were mainly on the handouts as well as notes written on other paper, including notebooks, loose leaf paper, or in textbooks.

Instruments

The achievement test for the “Memory” lesson unit was used to evaluate students’ academic performance. The test was a summative evaluation for the unit. It consisted of sixteen multiple-choice items and six essay items with standard answers. The items were designed by the researcher based on a two-way specification table (i.e., content × cognitive objectives). Afterward, two general psychology professors helped to evaluate and refine the items. In addition to content validity, the test score was positively correlated with the mean score of the following three unit tests in the course (r = .54, p < .01).

In addition to the achievement test, an after-class note-taking questionnaire was developed to survey the details of taking notes after class, including the note-taking activities, note-taking timing, reference information, and any help that was sought. The questions were drafted by the researcher and revised with input from twelve sophomore students who had taken the course previously.

Procedure

One week before the memory lesson started, the class was invited to take part in the study and was also informed about how the data would be collected: in the following 4 weeks, participants’ in-class notes would be collected at the end of each class, copied, and returned. As study strategies vary from one person to another, participants would not be required to take notes or use a particular note-taking method. Participants were required to maintain their usual note-taking habits. They were also assured that the data would be used solely for research purposes and would have no impact on their final marks. The entire class agreed to participate in the study.

Over the following 4 weeks, in-class notes were collected at the end of each class, copied, and returned to students. At the end of the lesson unit, notes collected over the 4 weeks were compiled as in-class notes. The achievement test was given 1 week later. For the sake of preventing students from taking after-class notes beyond their usual habits of note-taking, the class was not informed about the collection of unit notes until the day of the test. After the test was over, the class was invited to participate in the following data collection: lecture notes on the whole lesson unit, which consisted of in-class notes and after-class notes, would be collected. The entire class received the invitation and handed in their lesson unit notes. Meanwhile, they filled in the after-class note-taking questionnaire.

Data Analysis

Note quantity analysis refers to the word count. The amount of Chinese characters recorded in the notes was counted. The scoring method of note quality was taken from Peverly et al. (2007). The researcher identified the content areas in the lecture and examined what content areas were included in students’ notes. The quality of the corresponding content area was rated on a 0–3 scale. A rating of 0 was given for incorrect or missing information, a rating of 1 if a topic was mentioned but not elaborated, a rating of 2 for an incomplete explanation, and a rating of 3 for a complete explanation. The sum of the scores from different content areas was the total score for note quality. In the study, there were a total of fifty-nine content areas corresponding with most of the lecture topics and subtopics; these are shown in the “Appendix” marked with a star. Quality scores could range from 0 to 177. Inter-rater agreement for the randomly chosen protocols was .92 (p < .01).

Students’ scores for note quantity, note quality, academic performance, and survey responses were filed and statistically analyzed with 18.0 SPSS for Windows.

Results

Quantity and Quality of the Notes

The study collected and examined two kinds of student’s lecture notes, in-class notes and unit notes, to determine the quantity and quality of in-class and after-class notes on the lesson lecture. In-class notes were a compilation of the lecture notes that were taken in class, while unit notes were a combination of the lecture notes that were taken in and after class during the 4 weeks of lesson lecture.

In terms of in-class notes, it was found that the mean score of in-class notes’ quantity was 1,291.08. The class averagely wrote 1,291.08 Chinese characters for the lesson lecture in class. After rating the quality of notes, it was found that the mean score of in-class notes’ quality was 76.32, or 43 % of the highest possible quality score (177). The result showed that students’ average quality of in-class notes for the lesson lecture was below half the overall desired quality.

In terms of unit notes, it was found that the mean score of unit notes’ quantity was 1,927.24. The class averagely wrote 1,927.24 Chinese characters for the lesson lecture in and after class. In addition, the mean score of unit notes’ quality was 84.03, or 47 % of the total possible score. It meant that students’ average quality of in-class and after-class notes for the lesson lecture was below half the overall desired quality.

After deducting in-class notes’ quantity from unit notes’ quantity, it was found that the mean score of after-class notes’ quantity was 636.16. During the 4 weeks of lesson lecture, the class on average added 636.16 Chinese characters to their lecture notes after class. Moreover, after deducting in-class notes’ quality from unit notes’ quality, it was found that the mean score of after-class notes’ quality was 7.71, or 4 % of the total possible score. This result indicated that students’ average quality of after-class notes for the lesson lecture only slightly increased the overall quality.

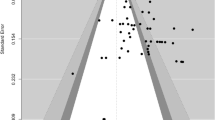

Predictive Analyses of Note Quantity and Quality to Academic Performance

In order to understand the predictive effects of note quantity and quality on academic performance, hierarchical regression analysis was used. First, the quantity and quality of in-class notes were used as predictive variables, with academic performance (test scores) used as the criterion variable for multiple regression analysis. As shown in Table 1, the regression model of the quantity and quality of in-class notes could predict academic performance (F(2, 35) = 7.32, p < .01) and account for 26 % of observed variances (Adj. R 2 = .26). In this model, only the quality of in-class notes significantly predicted academic performance, with positive predictive power (β = .60, p < .01).

Moreover, the quantity and quality of in-class and after-class notes were used as predictive variables, with academic performance (test scores) as the criterion variable for multiple regression analysis. As shown in Table 1, the regression model of the quantity and quality of in-class notes plus after-class notes could predict academic performance (F(4, 35) = 3.54, p < .05) and explain 22 % of the observed variances (Adj. R 2 = .22). In the model, the quality of in-class notes was the only significant predictor of academic performance, with positive predictive power (β = .60, p < .01). The numbers show that the addition of the quantity and quality of after-class notes to the model only weakened the level of explanation for academic performance.

After-Class Lecture Note-Taking Activities

As shown above, students took lectures notes not only in class but also after class. A survey was conducted to further understand how students took lecture notes after class. It found that the most frequent note-taking activities students participated in after class were making additions to in-class notes (71.1 %) and making corrections to in-class notes (63.2 %); fewer were reorganizing in-class notes (31.2 %) or rewriting notes (28.9 %). In terms of note-taking activity timing, only a small portion of students took notes after class each week (13.2 %); 39.5 % of the students took notes after a period of time after class; 47.4 % of the students did not take notes until days before the test. In terms of references, 63.6 % of the students accessed books and online information. The course textbook was most commonly used (39.5 %), followed by other textbooks (23.7 %) and the Internet (15.8 %). Few students accessed books other than textbooks (5.3 %). In terms of the help that was sought, up to about 89.5 % of the students sought help from others. Most students sought help from classmates (86.8 %), while fewer sought help from teachers (18.4 %) and senior classmates (13.2 %).

Discussion

The study found that the in-class notes were not of high quality and only half way to reaching the desired standards of the teacher’s lecture key points. This discovery was consistent with previous studies (Baker and Lombardi 1985; McDonald and Taylor 1980). In addition, the study found that even additions, adjustments, and reorganizations made to the notes after class did not lead to any noticeable improvement to the quality of the notes. The finalized lecture notes only half covered all of the key lecture points. Possible explanations are: first, as unit notes covered 2.63 more content areas than in-class notes (in-class notes 41.71; unit notes 44.34), it showed that students only made supplements or adjustments to in-class notes and did not make up for missed content areas after class, so the improvement of the quality of their notes was limited. Second, although some students responded in the questionnaire that they rewrote notes after class, a comparison between in-class and unit notes indicated that they only copied their original notes elsewhere, which did not help to improve the quality of the notes. Moreover, the questionnaire survey found that only a small proportion of students spent time taking notes after class each week and that most students postponed note-taking till later or days before the test. The prolonged time between encoding and reviewing made it difficult for students to brush up on what was said in the lecture and resulted in little improvement in note quality.

Both the in-class predictive model and in-class plus after-class predictive model provided certain levels of explanations for academic performance and reflected the encoding and reviewing functions of notes. As the quantity (word count) of the notes did not help to predict academic performance as the quality of the notes did, it is better to take good notes than to take more notes during class. A surprising discovery in the study was that the in-class predictive model provided better explanatory power for academic performance than the in-class plus after-class predictive model did. Moreover, the quality of after-class notes could not serve as a predictor of academic performance. By comparing students’ notes with each other, it was found that some students’ after-class notes were the same as others’ in-class notes, which suggests the likelihood that students would copy each other’s notes after class. One possible reason is that the process of transcribing verbatim cannot stimulate semantic analysis (Bretzing and Kulhavy 1979). The improvement in the quality of notes after class was only superficial and students could not benefit from it so their academic performance did not improve.

Implications and Limitations

Targeting a lesson unit, the present study advances the understanding of college students’ in-class and after-class lecture note-taking, as well as their effects on academic performance. Based on the results, the results of this study have implications for educational practice as well as for future research. For educational practice, the findings of the study show that the quality of in-class notes is an important factor in predicting academic performance and that the quality of Taiwanese students’ in-class notes is unsatisfactory. It is suggested that Taiwanese college teachers should pay more attention to their students’ in-class note contents and provide appropriate intervention to help enhancing the quality of their notes.

The study investigates college students’ lecture note-taking after class and reveals expected and unexpected findings. As expected, college students are not active, effective note-takers. They often postpone note-taking after class and the quality of after-class notes is poor. Surprisingly, the quality of after-class notes cannot effectively predict academic performance. Prior research has not dealt with the relation between after-class lecture note-taking and academic performance; the findings can serve as a temporary conclusion to provide reference for future researchers. Future research might discover the factors that moderate the effects of after-class notes’ quality on academic performance. It is suggested that students’ after-class note-taking procedures and theories about after-class note-taking should be explored in greater depth.

Some limitations might moderate the implications derived from the study. First, the study examines students’ lecture note-taking in a specific subject of social sciences. The findings of the study cannot be generalized to subjects other than social sciences unless they are validated further in those subjects. Second, past studies have found that the provision of instructor’s notes, types of instructor-provided notes, and the timing of when instructor’s notes are provided affect students’ note-taking and academic performance (Austin et al. 2004; Gee 2011; Katayama and Crooks 2003; Kiewra 1985; Raver and Maydosz 2010). In the study, the instructor provided skeleton notes to the students before the lecture started. The study findings can only be generalized to the situation where instructor provided partial or skeleton notes in advance. Finally, the findings of the study are mainly drawn from Taiwanese college students. Student’s cultural differences should also be considered in the generalization of the results.

References

Austin, J. L., Lee, M., & Carr, J. P. (2004). The effects of guided notes on undergraduate students’ recording of lecture content. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 31(4), 314–320.

Baker, L., & Lombardi, B. R. (1985). Students’ lecture notes and their relation to test performance. Teaching of Psychology, 12, 28–32.

Bonner, J. M., & Holliday, W. G. (2006). How college science students engage in note-taking strategies. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 43(8), 786–818.

Bretzing, B. H., & Kulhavy, R. W. (1979). Notetaking and depth of processing. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 4, 145–153.

Carter, J. F., & Van Matre, N. H. (1975). Note taking versus note having. Journal of Educational Psychology, 67(6), 900–904.

Castello, M., & Monereo, C. (2005). Students’ note-taking as a knowledge-construction tool. Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 5, 265–285.

Cukras, G. G. (2006). The investigation of study strategies that maximize learning for underprepared students. College Teaching, 54(1), 194–197.

Di Vesta, F. J., & Gray, G. S. (1972). Listening and note-taking. Journal of Educational Psychology, 63, 8–14.

Di Vesta, F. J., & Gray, G. S. (1973). Listening and note taking II: Immediate and delayed recall as functions of variations in thematic continuity, note taking, and length of listening-review intervals. Journal of Educational Psychology, 64, 278–287.

Dyson, B. J. (2008). Assessing small-scale interventions in large-scale teaching. Active Learning in Higher Education, 9(3), 265–282.

Einstein, G. O., Morris, J., & Smith, S. (1985). Note-taking, individual differences and memory for lecture information. Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 522–532.

Fisher, J. L., & Harris, M. B. (1973). Effect of note taking and review on recall. Journal of Educational Psychology, 65(3), 321–325.

Gee, K. L. (2011). The impact of instructor-provided lecture notes and learning interventions on student note-taking and generative processing. Thesis of San Jose State University, California, USA.

Isaacs, G. (1994). Lecturing practices and note-taking purposes. Studies in Higher Education, 19(2), 203–216.

Kam, M., Wang, J., Iles, A., Tse, E., Chiu, J., Glaser, D., Tarshish, O., & Canny, J. (2005). Livenotes: A system for cooperative and augmented note-taking in lectures. In Proceedings of conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 531–540). New York: ACM.

Katayama, A. D., & Crooks, S. M. (2003). Online notes: Differential effects of studying complete or partial graphically organized notes. Journal of Experimental Education, 71(4), 293–312.

Kiewra, K. A. (1985). Providing instructor’s notes: An effective addition to student note-taking. Educational Psychologist, 20(1), 33–39.

Kiewra, K. A. (1989). A review of note-taking: The encoding-storage paradigm and beyond. Educational Psychology Review, 1, 147–172.

Kiewra, K. A. (1997). Learning to learn: Making the transition form student to life-long learner. London: Allyn and Bacon.

Kobayashi, K. (2005). What limits the encoding effect of note-taking? A meta-analytic examination. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 30, 242–262.

Kobayashi, K. (2006). Combined effects of note-taking/reviewing on learning and the enhancement through interventions: A meta-analytic review. Educational Psychology, 26(3), 459–477.

Kuo, C. L. (2011). The relationship between learning motivation and lecture note-taking among college students. Thesis of the Department of Educational Psychology and Counseling. National Pingtung University of Education, Taiwan.

McDonald, R. J., & Taylor, E. G. (1980). Student note-taking and lecture handouts in veterinary medical education. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 7, 157–161.

Morales, J. D. (2004). An improved tool for taking class notes in the classroom. Thesis of University of Texas at El Paso, Texas, USA.

Palmatier, R. A., & Bennett, J. M. (1974). Notetaking habits of college students. Journal of Reading, 18, 215–218.

Pauk, W. (1974). How to study in college. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Peper, R. J., & Mayer, R. E. (1986). Generative effects of note-taking during science lectures. Journal of Educational Psychology, 78, 34–38.

Peverly, S. T., Ramaswamy, V., Brown, C., Sumowski, J., Alidoost, M., & Garner, J. (2007). What predicts skill in lecture note taking? Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(1), 167–180.

Plaue, C., LaMarca, S., & Funk, S. H. (2012). Group note-taking in a large lecture class. In Proceedings of the 43rd ACM technical symposium on computer science education (pp. 227–232). New York: ACM.

Raver, S. A., & Maydosz, A. S. (2010). Impact of the provision and timing of instructor-provided notes on university students’ learning. Active Learning in Higher Education, 11(3), 189–200.

Risch, N. L., & Kiewra, K. A. (1990). Content and form variations in note taking. Journal of Educational Research, 83(6), 355–357.

Shieh, R. S., Chang, W., & Tang, J. (2010). The impact of implementing technology-enabled active learning (TEAL) in university physics. The Asia-Pacific Educational Researcher, 19(3), 401–415.

Smith, E. E., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Fredrickson, B. L., & Loftus, G. R. (2009). Atkinson’s and Hilgards’ introduction to psychology (15th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Learning.

Titsworth, B. S., & Kiewra, K. A. (2004). Spoken organizational lecture cues and student notetaking as facilitators of student learning. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 29, 447–461.

Van Meter, P., Yokoi, L., & Pressley, M. (1994). College students’ theory of note-taking derived from their perceptions of note-taking. Journal of Educational Psychology, 86(3), 323–338.

Weiland, A., & Kingsbury, S. J. (2001). Immediate and delayed recall of lecture material as a function of note taking. Journal of Educational Research, 72, 228–230.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Science Council, Taiwan, under the grant number NSC 97-2410-H-153-001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Content of Lecture Slides

Appendix: Content of Lecture Slides

Note the following star marks (*) are to indicate the content areas in the study. They did not appear in actual slides.

Slide #1 |

Unit Six: Memory |

Slide #2 |

Introduction: An Example of Memory Error * |

Slide #3 |

Three Important Distinctions about Memory |

1. Three stages of memory |

(1) Encoding—Storage—Retrieval * |

(2) Biological evidence * |

Slide #4 |

Three Important Distinctions about Memory (continued) |

2. Three memory stores (The Akinson-Shiffrin theory) * |

(1) Sensory store * |

(2) Short-term store * |

(3) Long-term store * |

Slide #5 |

Three Important Distinctions about Memory (continued) |

3. Different memories for different kinds of information |

(1) Explicit memory * |

(2) Implicit memory * |

Slide #6 |

Sensory Memory |

1. Different kinds of sensory memories * |

Slide #7 |

Sensory Memory (continued) |

2. Iconic memory |

(1) Sperling’s experiments * |

(2) Di Lollo’s experiments * |

(3) A theory that integrates them * |

Slide #8 |

Working Memory |

1. Short-term memory → Working memory * |

Slide #9 |

Working Memory (continued) |

2. Encoding |

(1) Phonological encoding * |

(2) Visual encoding * |

(3) Two working memory systems * |

Slide #10 |

Working Memory (continued) |

3. Storage |

(1) Capacity * |

(2) Chunking * |

(3) Forgetting * |

Slide #11 |

Working Memory (continued) |

4. Retrieval |

(1) Sternberg memory-scanning task * |

(2) Two interpretations * |

Slide #12 |

Working Memory (continued) |

5. Working memory and thought |

(1) Problem-solving processes * |

(2) Language processes * |

Slide #13 |

Working Memory (continued) |

6. Transfer from working memory to long-term memory |

(1) Maintenance rehearsal versus Elaborative rehearsal * |

(2) Primacy effect versus Recency effect * |

(3) Division of brain labor between working memory and long-term memory * |

Slide #14 |

Long-term Memory |

1. Duration * |

Slide #15 |

Long-term Memory (continued) |

2. Encoding * |

Slide #16 |

Long-term Memory (continued) |

3. Retrieval |

(1) Retrieval failures * |

(2) Evidences |

A. Recall afterwards * |

B. Tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon * |

C. Repressed memories * |

D. Retrieval cues * |

Slide #17 |

Long-term Memory (continued) |

(3) Interference |

A. Proactive interference versus Retroactive interference * |

B. Ebbinghaus’s forgetting curve * |

Slide #18 |

Long-term Memory (continued) |

(4) Models of retrieval * |

Slide #19 |

Long-term Memory (continued) |

4. Storage: Loss of information from storage * |

Slide #20 |

Long-term Memory (continued) |

5. Interactions between encoding and retrieval |

(1) Organization * |

(2) Context * |

Slide #21 |

Long-term Memory (continued) |

6. Emotional factors in forgetting |

(1) Rehearsal * |

(2) Flashbulb memories * |

(3) Retrieval interference via anxiety * |

(4) Context effects * |

(5) Repression * |

Slide #22 |

Implicit Memory |

1. Definition * |

2. Amnesia |

(1) Anterograde amnesia versus Retrograde amnesia * |

(2) Skills and priming * |

Slide #23 |

Implicit Memory (continued) |

3. Childhood amnesia |

(1) Recall of an early memory * |

(2) Reasons for memory loss * |

Slide #24 |

Implicit Memory (continued) |

4. A variety of memory systems |

(1) Two kinds of explicit memory * |

(2) Implicit memory in normal individuals * |

Slide #25 |

Improving Memory |

1. Chunking and memory scan * |

2. Imagery and encoding |

(1) Method of loci * |

(2) Key-word method * |

Slide #26 |

Improving Memory (continued) |

3. Elaboration and encoding * |

4. Context and retrieval * |

Slide #27 |

Improving Memory (continued) |

5. Organization * |

6. Practicing retrieval * |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, PH. The Effects of College Students’ In-Class and After-Class Lecture Note-Taking on Academic Performance. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 22, 173–180 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-012-0010-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-012-0010-8