Abstract

Over the past several decades, periodization has been widely accepted as the gold standard of training theory. Within the literature, there are numerous definitions for periodization, which makes it difficult to study. When examining the proposed definitions and related studies on periodization, problems arise in the following domains: (1) periodization has been proposed to serve as the macro-management of the training process concerning the annual plan, yet research on long-term effects is scarce; (2) periodization and programming are being used interchangeably in research; and (3) training is not periodized alongside other stressors such as sport (i.e., only resistance training is being performed without the inclusion of sport). Overall, the state of the literature suggests that the inability to define periodization makes the statement of its superiority difficult to experimentally test. This paper discusses the proposed definitions of periodization and the study designs which have been employed to examine the concept.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Periodization has been proposed to serve as the macro-management of the training process concerning the annual plan, yet research on long-term effects is scarce. |

The terms ‘periodization’ and ‘programming’ are being used interchangeably in research leading to confusion over a proper definition. |

Training is not periodized alongside other stressors such as sport (i.e., only resistance training is being performed without the inclusion of sport), which may limit the ability to demonstrate the importance of periodization. |

1 Introduction

The theory of training has historically been discussed as a quest for improved physical performance. Particularly, periodization has attracted widespread interest in the exercise and sports science literature. The theory of periodization was published in the Russian monograph by Leonid Matveyev (1964), which summarized information on periodization of training and proposed a general approach to planned training [1]. Since then, this theoretical training concept has spread around the world and later appeared in work by Stone et al. in the United States [2]. Research has been conducted utilizing various periodized models such as reverse linear [3], block [4], and undulating approaches [5]. Although these models differ in structure and supporting rationale, they share a foundation in that they are based on the stress response as outlined by Hans Selye in the general adaptation syndrome (GAS) [6]. According to Selye, if not managed properly, stress will result in a general adaptation syndrome which is typically denoted by tissue degeneration and death. Although there is debate as to whether a general adaptation syndrome can occur following resistance exercise in humans [7,8,9,10], sports science developed modern periodization as a means to better manage the stress of exercise and prevent the consequences as noted by Selye (the GAS). Within the sports science literature, the “syndrome” denoted by Selye ended with exhaustion (noted by death of the organism). This final phase (exhaustion) has been replaced with “overtraining [11]”. Thus, periodization attempts to manage the stress of exercise to avoid the consequences associated with overtraining to achieve “peak” performance at a specific time.

Buckner et al. [7, 12] have recently questioned the efficacy of this theoretical framework underlying periodization, and whether periodization is superior to non-periodized resistance training for increasing muscle size and strength. Although this is a debated topic [13], the ability to interpret periodization literature may be hindered by the absence of a universally accepted definition of what periodization actually is. The current works of literature often describe any form of planned training indiscriminately as periodization regardless of the structure [14], making an appropriate definition of periodization difficult to decipher. For example, some definitions of periodization describe the long-term training management of stress [15,16,17], while other definitions focus more on short-term variations in training variables [18,19,20]. Furthermore, the scientific strategies employed to examine periodization may not support all definitions proposed in the literature. The purpose of this paper is to review the various definitions of periodization throughout the literature. Furthermore, we will examine the scientific procedures that have been employed to provide evidence for the theory or strategy of periodization.

2 The State of the Definition

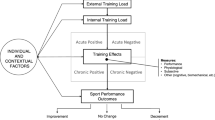

There is little agreement on a universally accepted definition of periodization, which may lead to disagreement about what specific components should make up a periodized program or plan. Without reaching an agreement on definition, scientific strategies employed to examine periodization may not be able to appropriately test its efficacy. In other words, do studies measure what they are supposed to measure to examine periodization? To advance the discussion, we created a list of previously used (peer-reviewed articles, textbooks, and expert’s opinions) definitions for periodization (Table 1). This examination of the literature is by no means exhaustive. The terms “periodized” and “periodization” were searched on PubMed and Google Scholar. The most cited papers were identified for further examination. In addition, textbooks available to authors were examined for definitions of periodization. From here, references of key papers and textbooks were examined for additional definitions. Due to the extensiveness of this body of literature, it was decided that the search would stop once 80 definitions were acquired. An additional seven definitions were added during the review process. In addition, many papers did not include a general definition of periodization, but provided a definition of a specific model of periodization. Thus, additional 41 definitions are provided in Table 2 which identify a specific periodized model. A similar strategy was used in constructing Fig. 1. 100 periodization interventions were identified to understand the experimental approach employed to examine periodization. When examining the proposed definitions and related studies on periodization, problems arise in the following domains:

-

Periodization has been proposed to serve as the macro-management of the training process concerning the annual plan [8, 17, 21], yet research on long-term effects is scarce.

-

The terms ‘periodization’ and ‘programming’ are being used interchangeably in research leading to confusion over a proper definition.

-

Training is not periodized alongside other stressors such as sport (i.e., only resistance training is being performed without the inclusion of sport), which may limit the ability to demonstrate the importance of periodization.

Numbers of periodized training studies for a given duration. Of 100 periodized training studies reviewed, 88 were examined within a 4–18 week time period. The authors of this review believe that the duration of these studies is too short to support the efficacy of periodization when the core concepts are centered around the yearlong plan and phasic adaptations. The details of each study (author, year, subject, design, and duration) are listed in Table 3

Overall, the state of the literature suggests that the inability to define periodization makes the statement of its superiority difficult to experimentally test. In addition, study designs may align with certain definitions of periodization while failing to address others. The subsequent sections will discuss the proposed definitions of periodization and the scientific strategies which have been employed to examine the concept.

3 Components of Periodization

3.1 Annual Plan

There is a wide array of definitions used to describe the concepts of periodization (Table 1). For example, multiple works of literature have proposed periodization to serve as the macro-management of the training process concerning the annual plan [18, 21,22,23,24,25]. Indeed, it is recommended that coaches begin the planning process by creating a sound annual plan (or larger time-period relevant to the sport of competition) to serve as a road map for the overall training process [17, 21, 25, 26]. The annual plan includes all training, competition, and associated endeavors to project the entire training year, while periodization is used to organize the annual plan into fitness phases and timelines [21,22,23,24]. Generally, periodized training can be divided into three stages: the macrocycle (long-length cycle, several months to a year or more), the mesocycle (middle-length cycle, 2–6 weeks), and the microcycle (short-length cycle, several days to 2 weeks) [25]. The structures of the meso- and microcycles are constructed based on the periods included in the macrocycle or annual plan. Thus, periodization divides the training plan into discrete cycles, phases, or blocks that focus on developing specific physiological adaptations (i.e., muscle hypertrophy, strength, power, speed, aerobic endurance, and others). Over time, the training program will typically progress from general to specific adaptations with the intention of bringing peak performance at competition time [8, 15, 25, 27].

3.2 Phase Potentiation

Another important facet of periodization is the strategic sequencing of physiological adaptations within the annual plan for the possibility of potentiation in subsequent training phases. Cunanan et al. [8] emphasize the efficacy of phase potentiation for long-term programming and the potential adverse effects of improper sequencing. Phase potentiation is the enhancement of subsequent training phases by the delayed (or residual) training effects produced from a previous training phase [21]. For example, prior exposure to strength training that focuses on maximal strength has been claimed to potentiate the gains in the rate of force development during a subsequent training phase that emphasizes power training [28]. Indeed, multiple works of literature and textbooks include phasic or sequential aspects in the definition of periodization [13, 17, 22, 25, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. For instance, the National Strength and Conditioning Association defines periodization as a: “theoretical and practical construct that allows for the systematic, sequential, and integrative programming of training interventions into mutually dependent periods of time to induce specific physiological adaptations that underpin performance outcomes [25]”. Thus, according to many sources, one might define periodization as an organizational approach to training that considers the competing stressors within an athlete’s life and creates “periods” of time dedicated to specific outcomes (i.e., strength, hypertrophy, or power). These designated periods are intended to manage the stress associated with exercise, while also creating potentiation in the subsequent training phases.

4 Scarcity of Research on Long-Term Effects

Although many definitions of periodization appear to stress organization of the annual plan and the influence of phase potentiation, experimental studies employed to study the concept of periodization do not seem to match this definition. Of the 100 periodized training studies that examined adaptations to various periodized training programs (i.e., linear periodization, undulating periodization, etc.), 88 followed participants for a 4–18 week time frame (Fig. 1, Table 3). We believe that the duration of these studies is too short to support the efficacy of periodization when the core concepts are modeled around the yearlong plan and phasic adaptations. Although there are some yearlong studies, they have been completed in untrained individuals [36] or published as a case report [31]. This may be problematic as the self-proclaimed goal of periodization is to structure the training process to stimulate specific physiological and performance outcomes at a specific timing (i.e., competition day) for athletes [15, 21, 22, 25, 29, 37, 38]. Therefore, the current works of literature fail to address the long-term effects of phasic structures of macro- and mesocycles, and it is still uncertain whether the effects of periodized training increase, maintain, or diminish over the long-term period of time. This discrepancy may be caused by the presence of varying definitions of what periodization actually is.

5 Periodization or Programming?

It has been discussed within the literature that “periodization” and “programming” are separate entities [8, 21, 26, 39]. In short, periodization is a global process that manages the training with respect to time, whereas programming involves the micromanagement of different phases of training by modifying the number of sets, repetitions, exercise selections, volume, load, frequency of training, and rest periods, amongst others [8, 21, 26]. Interestingly, the inconsistency of definitions used in the periodization literature (Table 1), as well as the scientific strategies that have been employed to examine periodization (Fig. 1, Table 3), make it challenging to distinguish between periodization and programming. Many definitions of periodization focus more on short-term variations in training variables [5, 18,19,20, 38, 40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59]. For example, Fleck and Kraemer (2004) define periodization as the following: “Periodization of training refers to planned changes in the acute training program variables of exercise order, exercise choice, number of sets, number of repetitions per set, rest periods between sets and exercise, exercise intensity, and number of training sessions per day in an attempt to bring about continued and optimal fitness gains [18]”. Here, the definition focuses on the acute changes in training variables rather than a global process within the long-term timeframe. This inconsistency is not limited to a few instances in the literature. Table 1 contains 87 general definitions of periodization. Of these 87 definitions of periodization, 25 represent programming [5, 18,19,20, 38, 40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59], whereas 62 represent a long-term approach. Some common themes in short-term definitions include the manipulation of training variables (i.e., load, volume, frequency, and exercise selections) throughout the training cycle. Such definitions stray away from what many may consider to be the core components of periodization [8, 26], which include the organization of the training plan into different phases and timelines and the management of stress to avoid overtraining. It is unclear which definition(s) of periodization is/are most appropriate; however, it seems that short-term studies have been accepted as the evidence for periodization. Overwhelmingly, the scientific approach to examine the efficacy of periodization [35, 60,61,62,63,64,65] can only be used as evidence for short term or “programming” definitions of periodization.

The confusion regarding the definition of periodization is further increased by the scientific strategies employed to study the concept. The majority of studies cited as evidence that a periodized resistance training program is superior to a non-periodized resistance training program have utilized study designs that align only with the definition of programming [34, 35, 60, 66]. This is evident in Fig. 1 and Table 3, which illustrate that periodization is being studied using mostly 8–12 week long studies. Many of these interventions focused on the manipulation of resistance training variables to maximize adaptations of muscle size and strength, failing to examine phase potentiation or the long-term projection of performance outcomes. Similarly, modern studies focus more on which model of periodization is superior to others over a relatively short time period [3,4,5, 20, 43, 48, 49, 56, 57, 63, 64, 67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78]. Table 3 demonstrates that 73 out of 100 periodized training studies utilize the intervention design that compares one periodization model versus different periodized model(s). For example, Rhea et al. (2002) compared the strength gains between daily undulating periodization and a linear periodization program over 12 weeks, and reported that a daily undulating periodized program elicited a greater percentage increase in strength compared to a linear periodized program [64]. Such studies may give some short-term insight, but ultimately they compare different programming strategies against one another and are inconsistent with longer term definitions of periodization.

6 Periodization Without Competing Stressors

One of the core concepts included in the definition of periodization is the stress/fatigue management to minimize the risk of overtraining [13, 15,16,17, 20, 40, 47, 51, 53, 77,78,79,80,81]. Overtraining has been defined as the accumulation of training stress resulting in long-term decrements in performance with or without associated physiological and psychological signs and symptoms of maladaptation [25, 82]. Indeed, some of the symptoms associated with overtraining (i.e., frequent injuries, sleep issues, and burnout) have been reported among various types of sports [83, 84]. In the context of periodization, overtraining occurs when there is an imbalance between the recovery and the summation of all stress related to training and sports events (i.e., sport-specific practices and competitions). Considering that the periodization of training was established to manage stress in conjunction with the sport [85], the management of overall stress plays a role to maximize performance outcomes.

To elicit desired training adaptations while managing fatigue and optimizing performance in line with the seasonal demand of sport, it is recommended to have an annual schedule that includes a preparatory, competitive, and transition phase [25, 29, 38]. Within this structure, the preparatory phase begins with higher volume/lower load training with an emphasis on developing a general physical base (i.e., muscle hypertrophy, strength endurance, and basic strength) to increase an athlete’s ability to tolerate more intense training [25]. A competitive phase is used to prepare an athlete for the competitive season by increasing strength and power via increasing training load while decreasing volume [29]. In addition, more emphasis is placed on sport-specific skills and tactics during this phase. The transition phase, often termed active rest, provides lower workloads to recuperate before preparation for the next competitive cycle [38]. Over the course of the year, the manipulation of training volume and load occurs with the intention of peaking performance at competition time. Thus, the concept of periodization would exist when the alteration of those training variables (i.e., load, volume, and frequency) is based around the competition demand in sport.

When coaches prescribe the resistance training program alongside sports practice, the level of the complexity to manage stress is greater compared to performing resistance training alone [39]. Numerous sports require an athlete to improve various types of physiological characteristics (i.e., anaerobic and aerobic capacity). As such, periodized training attempts to manage the total physical demand of an athlete’s time spent in sport with that spent on strength and conditioning. Indeed, other stressors should also be considered. For example, Stults-Kolehmainen et al. [86] demonstrated the capacity for psychological factors to influence recovery following strenuous resistance exercise. However, it may be assumed the sport and strength and conditioning provide the two primary physical stressors. Kraemer et al. (2003) investigated whether a nonlinear periodized resistance training program would result in superior training adaptations compared to a non-periodized program in competitive female tennis players [53]. Over the 9 months, the periodized training group rotated the loading schemes; 4–6 RM, 8–10 RM, and 12–15 RM over workouts on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, respectively. The non-periodized group performed a traditional moderate loading scheme (8–10 RM) in which the relative intensity of load remained constant throughout the intervention. The volume was equated between the groups. Although the authors concluded that periodization of resistance training produced a greater magnitude of improvement in strength and sport-specific skill (the percent increases in the ball velocities for serve, forehand stroke, and backhand stroke) compared to the non-periodized training program, the majority of the strength gains in 1RM bench press were observed during the first 4 months only in the periodized training group. Similarly, the gain in 1RM shoulder press plateaued after 6 months only in the periodized training group. On the other hand, the non-periodized group continued to experience improvements in 1RM of both bench press and shoulder press. By the end of 9 months, 1RM of bench press performance increased by 23% and 17% in the periodized and non-periodized training groups, respectively. In terms of the gains in shoulder press 1RM strength, the periodized and non-periodized groups increased by 24% and 23% after the 9 months of training, respectively. The authors attributed the inability to continually improve over the entire periodized training program to the potential upper limits of physiological adaptation, as the last 3.5 months of training were performed in conjunction with the competitive season [53]. Indeed, the goal of periodization is to balance the stress of lifting weights with the stress of sport and other life stressors. However, the results of Kraemer et al. [53] might suggest that periodization failed to result in continued gains throughout the competitive season. Furthermore, Kraemer et al. [53] did not vary the volume between the periodized and non-periodized groups (athletes performed the same routine the entire study). Thus, any differences between groups would be a result of one condition’s habitual programming versus the other group’s habitual programming. It seems reasonable to suggest that this study does not study periodization defined by a long-term training plan, but instead studies a version of periodization that is defined as programming. One group had one program strategy for 9 months and the other group had a different programming strategy for 9 months. The only aspect that may suggest components of longer term definitions of periodization is the mention that the number of resistance training sessions would decrease from three sessions per week to two sessions per week if there was an increase in the number of tennis matches (consideration of competing stressors). However, the change in number of sessions to account for the stress of tennis was the same between periodized and non-periodized groups.

Since periodization attempts to manage the overall stress to avoid the consequences associated with overtraining while increasing performance [8], studies examining periodization would better test the theory when training is periodized against the sport. However, the scientific discussion of periodization seems to occur (often times) without considering the competition demand of sport (i.e., in-season stress), with some exceptions [53, 87]. Procedures employed to examine periodization are rarely conducted with competitive athletes in the yearlong season, and the majority of studies only include the stress of lifting weights (i.e., resistance training program) without adding the stress from sport. Admittedly, this is a difficult concept to study considering coaches and athletes would be reluctant to surrender their strength and conditioning practices for the advancement of scientific knowledge. As a result, there are large gaps between the theoretical concepts of periodization and empirical evidence to support the usefulness of periodization in the context of the sport.

7 Suggestions for Future Research

An examination of the scientific literature studying periodization will quickly lead to the conclusion that periodization has been studied primarily in using short-term study designs (what most would consider the duration of a single or possibly two mesocycles). Within a period of 8–12 weeks, it is unlikely that an individual is at risk of overtraining and would require manipulations in training volume or intensity of load. Using Stone et al. [2] as an example:

Stone et al. compared a periodized program to a non-periodized program in a group of college aged males enrolled in a weight training class. Both groups trained three times per week. However, the non-periodized group performed 3 sets of a 6 repetition maximum (RM) on all exercises for the entire 6-weeks; whereas, the periodized group performed 5 sets of a 10RM for the first three weeks, followed by 5 sets of a 5RM for week 4, 3 sets of a 3RM for week 5 and 3 sets of a 2RM for week 6. According to the present literature review, the purpose of periodization is to avoid overtraining and potentially peak performance at a specific time. The first part of this definition is not addressed by this study design. There is little to no risk of overtraining from performing 3 sets of a 6RM for 6 weeks. Thus, the purpose of changing volume in this study was not to avoid overtraining. If there is no risk of overtraining, then programming can simply be designed with the intention of maximizing the strength or performance variables that are of interest (1RM squat and vertical jump in the case of Stone et al.).

Although studies like Stone et al. [2] are often accepted as evidence for (or against) periodization, the concept would be better studied in a sport context where there are competing stressors and an opportunity to employ strategic techniques aimed at managing recovery. Painter et al. conducted two studies [28, 88] comparing different periodized programming models in track and field athletes; however, their studies were limited to 10 weeks. Thus, we would suggest study designs like that employed by Kraemer et al. who examined whether a nonlinear periodized resistance training program would result in superior training adaptations compared to a non-periodized program in competitive female tennis players on a 9-month time period [53]. The authors conducted a study where one group performed a different repetition scheme throughout each week (4–6 RM, 8–10 RM, and 12–15 RM on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, respectively), and the non-periodized group performed a moderate loading scheme (8–10 RM) which remained constant throughout the intervention. This study is set up nicely to compare a periodized program versus a non-periodized program. However, volume was equated between the groups. This is problematic as a periodized program would decrease volume during the sport season to account for sport. Thus, we would suggest that both of these programs actually employed periodization (they both reduced the number of resistance training sessions during the season). Future studies might use a similar study design as Kraemer et al. However, the periodized group should employ specific periods of time dedicated to different attributes believed important for the sport (i.e., hypertrophy, strength, speed/power, and others). At the same time, periodization should consider the total stress of the strength and conditioning program and decreasing training volume when sport demand increases. This can be compared to a group that does a similar rep scheme indefinitely (while still employing progressive overload). The non-periodized group might also continue their normal training throughout the sports season. This study design would reflect the majority of definitions of periodization provided in the literature. Such study designs are undoubtedly difficult, and might be best examined in recreational sport or amateur sport looking to incorporate resistance exercise.

8 Conclusion

Over the past several decades, periodization has been accepted as the gold standard of training theory, yet there is a wide variety of definitions used to describe the concepts of periodization, making an appropriate definition of periodization difficult to decipher. Among others, periodization has been proposed to serve as the macro-management of the training process within the annual plan. However, long-term studies with competitive athletes are scarce. If periodization serves as the macro-management of the training within the annual timeline, any claims made regarding the benefits of periodization should be based on the studies that have a similar timeframe. Nevertheless, the evidence used to support the efficacy of periodization is centered around short-term studies that do not capture the overall picture of the annual process and performance outcomes. Hence, the scientific procedures employed to examine periodization do not seem to line up with the proposed definitions. As such, it is still uncertain whether the effects of periodized training increase, maintain, or diminish over the long-term period of time. Instead, current works of literature focus more on the comparison between different models of periodization over a relatively short time-period. To bridge the gap between the theory and practice of periodization, future research could conduct experiments with competitive and recreational athletes in the context of the yearlong season to advance further discussion. This will include the examination of the effects of each phasic structure associated with macro- and mesocycles, and the long-term projection of performance outcomes. Finally, a universal definition of periodization should be established. Based on a review of the literature, we would suggest the following definition:

Periodization is an organizational approach to training that considers the competing stressors within an athlete’s life and creates “periods” of time dedicated to specific outcomes (i.e., strength, hypertrophy or power). These designated periods are intended to manage the stress associated with exercise, while also creating potentiation in the subsequent training phases. Through proper stress management and program design this approach may also attempt to peak various performance measures at a specific time relevant to competition.

References

Matveyev LP. Problem of periodization the sport training. Moscow: FiS Publisher; 1964.

Stone MH, O’Bryant H, Garhammer J. A hypothetical model for strength training. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1981;21(4):342–51.

Prestes J, De Lima C, Frollini AB, Donatto FF, Conte M. Comparison of linear and reverse linear periodization effects on maximal strength and body composition. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(1):266–74.

Bartolomei S, Hoffman JR, Merni F, Stout JR. A comparison of traditional and block periodized strength training programs in trained athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(4):990–7.

Apel JM, Lacey RM, Kell RT. A comparison of traditional and weekly undulating periodized strength training programs with total volume and intensity equated. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(3):694–703.

Selye H. Experimental evidence supporting the conception of “adaptation energy.” Am J Physiol. 1938;123(3):758–65.

Buckner SL, Mouser JG, Dankel SJ, Jessee MB, Mattocks KT, Loenneke JP. The general adaptation syndrome: potential misapplications to resistance exercise. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20(11):1015–7.

Cunanan AJ, DeWeese BH, Wagle JP, Hornsby WG III, Carroll KM, Sausaman R, et al. The general adaptation syndrome: a foundation for the concept of periodization. Sports Med. 2018;4:787.

Buckner SL, Jessee MB, Dankel SJ, Mouser JG, Mattocks KT, Loenneke JP. Comment on: “the general adaptation syndrome: a foundation for the concept of periodization.” Sports Med. 2018;48(7):1751–3.

Cunanan AJ, DeWeese BH, Wagle JP, Carroll KM, Sausaman R, Hornsby WG, et al. Authors’ reply to Buckner et al.: ‘comment on: “the general adaptation syndrome: a foundation for the concept of periodization.” Sports Med. 2018;48(7):1755–7.

Stone MH, O’Bryant H, Garhammer J, McMillan J, Rozenek R. A theoretical model of strength training. Strength Cond J. 1982;4(4):36–9.

Buckner SL, Jessee MB, Mouser JG, Dankel SJ, Mattocks KT, Bell ZW, et al. The basics of training for muscle size and strength: a brief review on the theory. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020;52(3):645–53.

Williams TD, Tolusso DV, Fedewa MV, Esco MR. Comparison of periodized and non-periodized resistance training on maximal strength: a meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2017;47(10):2083–100.

Kiely J. Periodization paradigms in the 21st century: evidence-led or tradition-driven? Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2012;7(3):242–50.

Plisk SS, Stone MH. Periodization strategies. Strength Cond J. 2003;25(6):19–37.

Harries SK, Lubans DR, Callister R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of linear and undulating periodized resistance training programs on muscular strength. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(4):1113–25.

DeWeese BH, Hornsby GW, Stone MH, Stone MH. The training process: planning for strength—power training in track and field. part 1: theoretical aspects. J Sport Health Sci. 2015;4:308–17.

Fleck SJ, Kraemer WJ, Kraemer PHDW. Designing resistance training programs. 3rd ed. Human Kinetics; 2004.

Brown LE, Bradley-Popovich G, Haff G. Nonlinear versus linear periodization models. Strength Cond J. 2001;23(1):42–4.

Buford TW, Rossi SJ, Smith DB, Warren AJ. A comparison of periodization models during nine weeks with equated volume and intensity for strength. J Strength Cond Res. 2007;21(4):1245–50.

Suchomel TJ, Nimphius S, Bellon CR, Stone MH. The importance of muscular strength: training considerations. Sports Med. 2018;48(4):765–85.

Hoffman JR, National S, Conditioning A. NSCA’s guide to program design. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 2012.

Bompa T. Primer on periodization. Olympic Coach. 2004;16(2):4–7.

Zatsiorsky V, Kraemer W. Science and practice of strength training. 2nd Ed. Human Kinetics; 2006.

Haff G, Triplett NT, National Strength & Conditioning Association. Essentials of strength training and conditioning. 4th Ed. Human Kinetics; 2016.

DeWeese BH, Hornsby GW, Stone MH, Stone MH. The training process: planning for strength–power training in track and field. Part 2: practical and applied aspects. J Sport Health Sci. 2015;4:318–24.

Zaryski C, Smith DJ. Training principles and issues for ultra-endurance athletes. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2005;4(3):165–70.

Painter KB, Haff GG, Ramsey MW, McBride J, Triplett T, Sands WA, et al. Strength gains: block versus daily undulating periodization weight training among track and field athletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2012;7(2):161–9.

Chandler TJ, Brown LE. Conditioning for strength and human performance. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

Issurin VB. New horizons for the methodology and physiology of training periodization. Sports Med. 2010;40(3):189–206.

Tonnessen E, Svendsen IS, Ronnestad BR, Hisdal J, Haugen TA, Seiler S. The annual training periodization of 8 world champions in orienteering. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2015;10(1):29–38.

Kiely J. Periodization theory: confronting an inconvenient truth. Sports Med. 2017;48(4):753–64.

Grgic J, Mikulic P, Podnar H, Pedisic Z. Effects of linear and daily undulating periodized resistance training programs on measures of muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3695.

Willoughby DS. The Effects of mesocycle-length weight training programs involving periodization and partially equated volumes on upper and lower body strength. J Strength Cond Res. 1993;7(1):2–8.

Stone MH, Potteiger JA, Pierce KC, Proulx CM, O’Bryant HS, Johnson RL, et al. Comparison of the effects of three different weight-training programs on the one repetition maximum squat. J Strength Cond Res. 2000;14(3):332–7.

Pinto R, Angarten V, Santos V, Melo X, Santa-Clara H. The effect of an expanded long-term periodization exercise training on physical fitness in patients with coronary artery disease: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20(1):208.

Kibler WB, Chandler TJ. Sport-specific conditioning. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(3):424–32.

Haff GG. Roundtable discussion: periodization of training—part 1. Strength Cond J. 2004;26(1):50–69.

Fisher PJ, Steele J, Smith D, Gentil P. Periodization for optimizing strength and hypertrophy; the forgotten variables. J Trainol. 2018;7(1):10–5.

Marx JO, Ratamess NA, Nindl BC, Gotshalk LA, Volek JS, Dohi K, et al. Low-volume circuit versus high-volume periodized resistance training in women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(4):635–43.

Herrick AB, Stone WJ. The effects of periodization versus progressive resistance exercise on upper and lower body strength in women. J Strength Cond Res. 1996;10(2):72–6.

DeBeliso M, Harris C, Spitzer-Gibson T, Adams KJ. A comparison of periodised and fixed repetition training protocol on strength in older adults. J Sci Med Sport. 2005;8(2):190–9.

Prestes J, Frollini AB, de Lima C, Donatto FF, Foschini D, de Cassia MR, et al. Comparison between linear and daily undulating periodized resistance training to increase strength. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(9):2437–42.

Foschini D, Araujo RC, Bacurau RF, De Piano A, De Almeida SS, Carnier J, et al. Treatment of obese adolescents: the influence of periodization models and ACE genotype. Obesity. 2010;18(4):766–72.

Mann JB, Thyfault JP, Ivey PA, Sayers SP. The effect of autoregulatory progressive resistance exercise vs. linear periodization on strength improvement in college athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(7):1718–23.

Fleck SJ. Non-linear periodization for general fitness & athletes. J Hum Kinet. 2011;29a:41–5.

Lorenz D, Morrison S. Current concepts in periodization of strength and conditioning for the sports physical therapist. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10(6):734–47.

Ullrich B, Holzinger S, Soleimani M, Pelzer T, Stening J, Pfeiffer M. Neuromuscular responses to 14 weeks of traditional and daily undulating resistance training. Int J Sports Med. 2015;36(7):554–62.

Bradbury DG, Landers GJ, Benjanuvatra N, Goods PSR. Comparison of linear and reverse linear periodized programs with equated volume and intensity for endurance running performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;34(5):1345–53.

Fleck SJ, Kraemer WJ. Periodization breakthrough!: the ultimate training system. 1st Ed. Advanced Research Press; 1996.

Schiotz MK, Potteiger JA, Huntsinger PG, Donald C, Denmark LC. The short-term effects of periodized and constant-intensity training on body composition, strength, and performance. J Strength Cond Res. 1998;12(3):173–8.

Graham J. Periodization research and an example application. Strength Cond J. 2002;24:62–70.

Kraemer WJ, Hakkinen K, Triplett-Mcbride NT, Fry AC, Koziris LP, Ratamess NA, et al. Physiological changes with periodized resistance training in women tennis players. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(1):157–68.

Plisk S. Periodization: fancy name for a basic concept. Olympic Coach. 2004;16(2):14–7.

Jiménez A. Undulating periodization models for strength training & conditioning. Motricidade. 2009;5:1–5.

Tammam A, Hashem E. Comparison between daily and weekly undulating periodized resistance training to increase muscular strength for volleyball players. J Appl Sports Sci. 2015;5(3):27–36.

Klemp A, Dolan C, Quiles JM, Blanco R, Zoeller RF, Graves BS, et al. Volume-equated high- and low-repetition daily undulating programming strategies produce similar hypertrophy and strength adaptations. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41(7):699–705.

Housh TJ, Housh DJ, deVries HA. Applied exercise and sport physiology, with labs. 3rd Ed. Taylor & Francis; 2011.

Vargas A. Tiered vs. traditional daily undulating periodization for improving powerlifting performance in trained males. Graduate Theses and Dissertations, University of South Florida; 2017. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6770.

Stowers T, McMillan J, Scala D, Davis V, Wilson D, Stone M. The short-term effects of three different strength-power training methods. Strength Cond J. 1983;5(3):24–7.

Harries SK, Lubans DR, Callister R. Comparison of resistance training progression models on maximal strength in sub-elite adolescent rugby union players. J Sci Med Sport. 2016;19(2):163–9.

Hoffman JR, Wendell M, Cooper J, Kang J. Comparison between linear and nonlinear in-season training programs in freshman football players. J Strength Cond Res. 2003;17(3):561–5.

Kok LY, Hamer PW, Bishop DJ. Enhancing muscular qualities in untrained women: linear versus undulating periodization. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(9):1797–807.

Rhea MR, Ball SD, Phillips WT, Burkett LN. A comparison of linear and daily undulating periodized programs with equated volume and intensity for strength. J Strength Cond Res. 2002;16(2):250–5.

Bartolomei S, Stout JR, Fukuda DH, Hoffman JR, Merni F. Block vs. weekly undulating periodized resistance training programs in women. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(10):2679–87.

O’Bryant HS, Byrd R, Stone MH. Cycle ergometer performance and maximum leg and hip strength adaptations to two different methods of weight-training. J Strength Cond Res. 1988;2(2):27–30.

Monteiro AG, Aoki MS, Evangelista AL, Alveno DA, Monteiro GA, Picarro Ida C, et al. Nonlinear periodization maximizes strength gains in split resistance training routines. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(4):1321–6.

McNamara JM, Stearne DJ. Flexible nonlinear periodization in a beginner college weight training class. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(1):17–22.

Miranda F, Simao R, Rhea M, Bunker D, Prestes J, Leite RD, et al. Effects of linear vs. daily undulatory periodized resistance training on maximal and submaximal strength gains. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(7):1824–30.

Simao R, Spineti J, de Salles BF, Matta T, Fernandes L, Fleck SJ, et al. Comparison between nonlinear and linear periodized resistance training: hypertrophic and strength effects. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(5):1389–95.

de Lima C, Boullosa DA, Frollini AB, Donatto FF, Leite RD, Gonelli PR, et al. Linear and daily undulating resistance training periodizations have differential beneficial effects in young sedentary women. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33(9):723–7.

Bakken TA. Effects of block periodization training versus traditional periodization training in trained cross country skiers. Student thesis, Swedish School of Sport and Health Sciences; 2013.

Ahmadizad S, Ghorbani S, Ghasemikaram M, Bahmanzadeh M. Effects of short-term nonperiodized, linear periodized and daily undulating periodized resistance training on plasma adiponectin, leptin and insulin resistance. Clin Biochem. 2014;47(6):417–22.

Zourdos MC, Jo E, Khamoui AV, Lee SR, Park BS, Ormsbee MJ, et al. Modified daily undulating periodization model produces greater performance than a traditional configuration in powerlifters. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(3):784–91.

Colquhoun RJ, Gai CM, Walters J, Brannon AR, Kilpatrick MW, D’Agostino DP, et al. Comparison of powerlifting performance in trained men using traditional and flexible daily undulating periodization. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31(2):283–91.

Pelzer T, Ullrich B, Pfeiffer M. Periodization effects during short-term resistance training with equated exercise variables in females. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2017;117(3):441–54.

Bartolomei S, Hoffman J, Stout J, Zini M, Stefanelli C, Merni F. Comparison of block versus weekly undulating periodization models on endocrine and strength changes in male athletes. Kinesiology. 2016;48:71–8.

Spineti J, Figueiredo T, de Salles B, Barbosa M, Oliveira L, Novaes J, et al. Comparison between different periodization models on muscular strength and thickness in a muscle group increasing sequence. Rev Bras Med Esporte. 2013;19:280–6.

Kenney WL, Wilmore JH, Costill DL. Physiology of sport and exercise. 7th Ed. Human kinetics, Incorporated; 2019.

Hartmann H, Wirth K, Keiner M, Mickel C, Sander A, Szilvas E. Short-term periodization models: effects on strength and speed-strength performance. Sports Med. 2015;45(10):1373–86.

Conlon JA, Newton RU, Tufano JJ, Banyard HG, Hopper AJ, Ridge AJ, et al. Periodization strategies in older adults: impact on physical function and health. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(12):2426–36.

Meeusen R, Duclos M, Foster C, Fry A, Gleeson M, Nieman D, et al. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science and the American College of Sports Medicine. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(1):186–205.

Kentta G, Hassmen P, Raglin JS. Training practices and overtraining syndrome in Swedish age-group athletes. Int J Sports Med. 2001;22(6):460–5.

Matos NF, Winsley RJ, Williams CA. Prevalence of nonfunctional overreaching/overtraining in young English athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(7):1287–94.

Matveev LP. Fundamentals of sports training. Moscow: Progress Publishers; 1981.

Stults-Kolehmainen MA, Bartholomew JB, Sinha R. Chronic psychological stress impairs recovery of muscular function and somatic sensations over a 96-hour period. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(7):2007–17.

Kraemer WJ, Ratamess N, Fry AC, Triplett-McBride T, Koziris LP, Bauer JA, et al. Influence of resistance training volume and periodization on physiological and performance adaptations in collegiate women tennis players. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(5):626–33.

Painter KB, Haff GG, Triplett NT, Stuart C, Hornsby G, Ramsey MW, et al. Resting hormone alterations and injuries: block vs. DUP weight-training among D-1 track and field athletes. Sports. 2018;6(1):3.

Pedemonte J. Updated acquisitions about training periodization: part one. Strength Cond J. 1982;4(5):56–60.

Freeman WH. Peak when it counts: periodization for American track and field. 4th Ed. Tafnews Press; 2001.

Smith DJ. A framework for understanding the training process leading to elite performance. Sports Med. 2003;33(15):1103–26.

Gambetta V. Periodization and the systematic sport development process. Olympic Coach. 2004;16(2):8–13.

Cissik J, Hedrick A, Barnes M. Challenges applying the research on periodization. Strength Cond J. 2008;30(1):45–51.

Issurin V. Block periodization versus traditional training theory: a review. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2008;48(1):65–75.

Peterson MD, Dodd DJ, Alvar BA, Rhea MR, Favre M. Undulation training for development of hierarchical fitness and improved firefighter job performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2008;22(5):1683–95.

Ratamess N, Alvar B, Evetoch TK, Housh TJ, Kibler WB, Kraemer W. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults [ACSM position stand]. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:687–708.

Kell RT. The influence of periodized resistance training on strength changes in men and women. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(3):735–44.

Turner A. The science and practice of periodization: a brief review. Strength Cond J. 2011;33(1):34–46.

Naclerio F, Moody J, Chapman M. Applied periodization: a methodological approach. J Hum Sport Exerc. 2013;8(2):S350–66.

DeWeese BH, Gray H, Sams M, Scruggs S, Serrano AJ. Revising the definition of periodization: merging historical principles with modern concern. Olympic Coach. 2013;24:5–18.

Horschig AD, Neff TE, Serrano AJ. Utilization of autoregulatory progressive resistance exercise in transitional rehabilitation periodization of a high school football-player following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a case report. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9(5):691–8.

Carter J, Potter A, Brooks K. Overtraining syndrome: causes, consequences, and methods for prevention. J Sport Human Perf. 2014;2:1–4.

Hoover DL, VanWye WR, Judge LW. Periodization and physical therapy: bridging the gap between training and rehabilitation. Phys Ther Sport. 2016;18:1–20.

Eifler C. Short-term effects of different loading schemes in fitness-related resistance training. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(7):1880–9.

Loturco I, Nakamura F. Training periodisation: an obsolete methodology? Aspetar Sports Med J. 2016.

Fairman CM, Zourdos MC, Helms ER, Focht BC. A scientific rationale to improve resistance training prescription in exercise oncology. Sports Med. 2017;47(8):1457–65.

Conlon JA, Newton RU, Tufano JJ, Penailillo LE, Banyard HG, Hopper AJ, et al. The efficacy of periodised resistance training on neuromuscular adaptation in older adults. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2017;117(6):1181–94.

Mujika I, Halson S, Burke LM, Balague G, Farrow D. An integrated, multifactorial approach to periodization for optimal performance in individual and team sports. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2018;13(5):538–61.

Boggenpoel BY, Nel S, Hanekom S. The use of periodized exercise prescription in rehabilitation: a systematic scoping review of literature. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32(9):1235–48.

Afonso J, Rocha T, Nikolaidis PT, Clemente FM, Rosemann T, Knechtle B. A systematic review of meta-analyses comparing periodized and non-periodized exercise programs: why we should go back to original research. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1023.

Evans JW. Periodized resistance training for enhancing skeletal muscle hypertrophy and strength: a mini-review. Front Physiol. 2019;10:13.

Hellard P, Avalos-Fernandes M, Lefort G, Pla R, Mujika I, Toussaint J-F, et al. Elite swimmers’ training patterns in the 25 weeks prior to their season’s best performances: insights into periodization from a 20-years cohort. Front Physiol. 2019;10:363.

Myakinchenko EB, Kriuchkov AS, Adodin NV, Feofilaktov V. The annual periodization of training volumes of international-level cross-country skiers and biathletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2020;1:1–8.

Baker D, Wilson G, Carlyon R. Periodization: the effect on strength of manipulating volume and intensity. J Strength Cond Res. 1994;8(4):235–42.

Hoffman JR, Ratamess NA, Klatt M, Faigenbaum AD, Ross RE, Tranchina NM, et al. Comparison between different off-season resistance training programs in Division III American college football players. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(1):11–9.

Reiman MP, Lorenz DS. Integration of strength and conditioning principles into a rehabilitation program. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2011;6(3):241–53.

Moraes E, Fleck SJ, Ricardo Dias M, Simao R. Effects on strength, power, and flexibility in adolescents of nonperiodized vs. daily nonlinear periodized weight training. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27(12):3310–21.

Souza EO, Ugrinowitsch C, Tricoli V, Roschel H, Lowery RP, Aihara AY, et al. Early adaptations to six weeks of non-periodized and periodized strength training regimens in recreational males. J Sports Sci Med. 2014;13(3):604–9.

Smith RA, Martin GJ, Szivak TK, Comstock BA, Dunn-Lewis C, Hooper DR, et al. The effects of resistance training prioritization in NCAA Division I Football summer training. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(1):14–22.

Inoue DS, De Mello MT, Foschini D, Lira FS, De Piano GA, Da Silveira Campos RM, et al. Linear and undulating periodized strength plus aerobic training promote similar benefits and lead to improvement of insulin resistance on obese adolescents. J Diabetes Complicat. 2015;29(2):258–64.

Androulakis-Korakakis P, Fisher JP, Kolokotronis P, Gentil P, Steele J. Reduced volume ‘daily max’’ training compared to higher volume periodized training in powerlifters preparing for competition-a pilot study.’ Sports (Basel). 2018;6(3):86.

Issurin VB. Biological background of block periodized endurance training: a review. Sports Med. 2019;49(1):31–9.

Ronnestad BR, Hansen J, Ellefsen S. Block periodization of high-intensity aerobic intervals provides superior training effects in trained cyclists. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(1):34–42.

Ronnestad BR, Hansen J, Thyli V, Bakken TA, Sandbakk O. 5-week block periodization increases aerobic power in elite cross-country skiers. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016;26(2):140–6.

Caldwell AM. A comparison of linear and daily undulating periodizied strength training programs [Student thesis]; 2004.

Loturco I, Nakamura FY, Kobal R, Gil S, Pivetti B, Pereira LA, et al. Traditional periodization versus optimum training load applied to soccer players: effects on neuromuscular abilities. Int J Sports Med. 2016;37(13):1051–9.

Ronnestad BR, Ofsteng SJ, Ellefsen S. Block periodization of strength and endurance training is superior to traditional periodization in ice hockey players. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2019;29(2):180–8.

Ullrich B, Pelzer T, Pfeiffer M. Neuromuscular effects to 6 weeks of loaded countermovement jumping with traditional and daily undulating periodization. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(3):660–74.

Gonelli P, Braz T, Verlengia R, Pellegrinotti Í, Cesar M, Sindorf M, et al. Effect of linear and undulating training periodization models on the repeated sprint ability and strength of soccer players. Motriz Revista de Educação Física. 2018;24:1–7.

McGee D, Jessee TC, Stone MH, Blessing D. Leg and hip endurance adaptations to three weight-training programs. J Strength Cond Res. 1992;6(2):92–5.

Sabido R, Hernández-Davó J, Botella Ruiz J, Jiménez-Leiva A, Fernandez-Fernandez J. Effects of block and daily undulating periodization on neuromuscular performance in young male handball players. Kinesiology. 2018;50:97–103.

Fink J, Kikuchi N, Yoshida S, Terada K, Nakazato K. Impact of high versus low fixed loads and non-linear training loads on muscle hypertrophy, strength and force development. Springerplus. 2016;5(1):698.

Franchini E, Branco BM, Agostinho MF, Calmet M, Candau R. Influence of linear and undulating strength periodization on physical fitness, physiological, and performance responses to simulated judo matches. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(2):358–67.

Marques M, Casimiro F, Marinho D, Costa A. Training and detraining effects on strength parameters in young volleyball players: volume distribution implications. Motriz. 2011;17:235–43.

Schoenfeld BJ, Contreras B, Ogborn D, Galpin A, Krieger J, Sonmez GT. Effects of varied versus constant loading zones on muscular adaptations in trained men. Int J Sports Med. 2016;37(6):442–7.

Pliauga V, Lukonaitiene I, Kamandulis S, Skurvydas A, Sakalauskas R, Scanlan AT, et al. The effect of block and traditional periodization training models on jump and sprint performance in collegiate basketball players. Biol Sport. 2018;35(4):373–82.

Javaloyes A, Sarabia JM, Lamberts RP, Plews D, Moya-Ramon M. Training prescription guided by heart rate variability vs. block periodization in well-trained cyclists. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;34(6):1511–8.

Harris GR, Stone MH, O’bryant HS, Proulx CM, Johnson RL. Short-term performance effects of high power, high force, or combined weight-training methods. J Strength Cond Res. 2000;14(1):14–20.

Clemente-Suarez VJ, Ramos-Campo DJ. Effectiveness of reverse vs. traditional linear training periodization in triathlon. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(15):2807.

Medeiros LHL, Sandbakk SB, Bertazone TMA, Bueno Junior CR. Comparison of periodization models of concurrent training in recreationally active postmenopausal women. J Strength Cond Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003559 (Epub ahead of print).

Pacobahyba N, Vale R, Legey S, Simão R, Santos E, Dantas E. Muscle strength, serum basal levels of testosterone and urea in soccer athletes submitted to non-linear periodization program. Rev Bras Med Esporte. 2012;18:130–3.

Storer TW, Dolezal BA, Berenc MN, Timmins JE, Cooper CB. Effect of supervised, periodized exercise training vs self-Directed training on lean body mass and other fitness variables in health club members. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(7):1995–2006.

Garcia-Pallares J, Sanchez-Medina L, Carrasco L, Diaz A, Izquierdo M. Endurance and neuromuscular changes in world-class level kayakers during a periodized training cycle. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;106(4):629–38.

Ronnestad BR, Ellefsen S, Nygaard H, Zacharoff EE, Vikmoen O, Hansen J, et al. Effects of 12 weeks of block periodization on performance and performance indices in well-trained cyclists. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(2):327–35.

Sylta Ø, Tønnessen E, Hammarström D, Danielsen J, Skovereng K, Ravn T, et al. The effect of different high-intensity periodization models on endurance adaptations. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(11):2165–74.

De Souza EO, Tricoli V, Rauch J, Alvarez MR, Laurentino G, Aihara AY, et al. Different patterns in muscular strength and hypertrophy adaptations in untrained individuals undergoing nonperiodized and periodized strength regimens. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(5):1238–44.

Gavanda S, Geisler S, Quittmann OJ, Schiffer T. The effect of block versus daily undulating periodization on strength and performance in adolescent football players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2019;14(6):814–21.

Harries SK, Lubans DR, Buxton A, MacDougall THJ, Callister R. Effects of 12-week resistance training on sprint and jump performances in mompetitive adolescent rugby union players. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(10):2762–9.

Rodrigues JAL, Santos BC, Medeiros LH, Goncalves TCP, Junior CRB. Effects of different periodization strategies of combined aerobic and strength training on heart rate variability in older women. J Strength Cond Res. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003013 (Epub ahead of print).

Boidin M, Trachsel LD, Nigam A, Juneau M, Tremblay J, Gayda M. Non-linear is not superior to linear aerobic training periodization in coronary heart disease patients. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319891778.

Tjønna AE, Sandbakk Ø, Skovereng K. The effects of systematic block versus traditional periodization on physiological and performance indicators of well-trained cyclists [Master Thesis]: NTNU; 2019.

Buskard A, Zalma B, Cherup N, Armitage C, Dent C, Signorile JF. Effects of linear periodization versus daily undulating periodization on neuromuscular performance and activities of daily living in an elderly population. Exp Gerontol. 2018;113:199–208.

Barjaste A, Mirzaei B. The periodization of resistance training in soccer players: changes in maximal strength, lower extremity power, body composition and muscle volume. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2018;58(9):1218–25.

Bessa A, Sposito-Araujo C, Senna G, Lopes T, Godoy E, Scudese E, et al. Comparison of the Matveev periodization model and the Verkhoshansky periodization model. J Exerc Physiol Online. 2018;21:60–7.

Hartmann H, Bob A, Wirth K, Schmidtbleicher D. Effects of different periodization models on rate of force development and power ability of the upper extremity. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(7):1921–32.

Kramer JB, Stone MH, O’Bryant HS, Conley MS, Johnson RL, Nieman DC, et al. Effects of single vs. multiple sets of weight training: impact of volume, intensity, and variation. J Strength Cond Res. 1997;11(3):143–7.

Rhea MR, Phillips WT, Burkett LN, Stone WJ, Ball SD, Alvar BA, et al. A comparison of linear and daily undulating periodized programs with equated volume and intensity for local muscular endurance. J Strength Cond Res. 2003;17(1):82–7.

Bezerra ES, Orssatto LBR, de Moura BM, Willardson JM, Simão R, Moro ARP. Mixed session periodization as a new approach for strength, power, functional performance, and body composition enhancement in aging adults. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(10):2795–806.

de Freitas MC, de Souza Pereira CG, Batista VC, Rossi FE, Ribeiro AS, Cyrino ES, et al. Effects of linear versus nonperiodized resistance training on isometric force and skeletal muscle mass adaptations in sarcopenic older adults. J Exerc Rehabil. 2019;15(1):148–54.

Jaimes DAR, Contreras D, Jimenez AMF, Orcioli-Silva D, Barbieri FA, Gobbi LTB. Effects of linear and undulating periodization of strength training in the acceleration of skater children. Motriz Revista de Educação Física. 2019;25(1):e101955.

de Assis LA, Werneck FZ, Junior DBR, Vianna JM. Effect of periodization on the physical capacities of basketball players of a military school. Rev Bras Cineantropom Desempenho Hum. 2019;21:59818.

Ullrich B, Pelzer T, Oliveira S, Pfeiffer M. Neuromuscular responses to short-term resistance training with traditional and daily undulating periodization in adolescent elite judoka. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(8):2083–99.

Manchado C, Cortell-Tormo JM, Tortosa-Martinez J. Effects of two different training periodization models on physical and physiological aspects of elite female team handball players. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(1):280–7.

Kraemer WJ, Nindl BC, Ratamess NA, Gotshalk LA, Volek JS, Fleck SJ, et al. Changes in muscle hypertrophy in women with periodized resistance training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(4):697–708.

Hunter GR, Wetzstein CJ, McLafferty CL Jr, Zuckerman PA, Landers KA, Bamman MM. High-resistance versus variable-resistance training in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(10):1759–64.

Vanni AC, Meyer F, da Veiga AD, Zanardo VP. Comparison of the effects of two resistance training regimens on muscular and bone responses in premenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(9):1537–44.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No external sources of funding were used in the preparation of this article.

Conflict of Interest

Ryo Kataoka, Ecaterina Vasenina, Jeremy Loenneke, and Samuel Buckner declare that they have no conflicts of interest that are relevant to the content of this article.

Authorship Contributions

RK, EV, SLB, and JPL wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kataoka, R., Vasenina, E., Loenneke, J. et al. Periodization: Variation in the Definition and Discrepancies in Study Design. Sports Med 51, 625–651 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01414-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01414-5