Abstract

Background

Expertise has been extensively studied in several sports over recent years. The specificities of how excellence is achieved in Association Football, a sport practiced worldwide, are being repeatedly investigated by many researchers through a variety of approaches and scientific disciplines.

Objective

The aim of this review was to identify and synthesise the most significant literature addressing talent identification and development in football. We identified the most frequently researched topics and characterised their methodologies.

Methods

A systematic review of Web of Science™ Core Collection and Scopus databases was performed according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) guidelines. The following keywords were used: “football” and “soccer”. Each word was associated with the terms “talent”, “expert*”, “elite”, “elite athlete”, “identification”, “career transition” or “career progression”. The selection was for the original articles in English containing relevant data about talent development/identification on male footballers.

Results

The search returned 2944 records. After screening against set criteria, a total of 70 manuscripts were fully reviewed. The quality of the evidence reviewed was generally excellent. The most common topics of analysis were (1) task constraints: (a) specificity and volume of practice; (2) performers’ constraints: (a) psychological factors; (b) technical and tactical skills; (c) anthropometric and physiological factors; (3) environmental constraints: (a) relative age effect; (b) socio-cultural influences; and (4) multidimensional analysis. Results indicate that the most successful players present technical, tactical, anthropometric, physiological and psychological advantages that change non-linearly with age, maturational status and playing positions. These findings should be carefully considered by those involved in the identification and development of football players.

Conclusion

This review highlights the need for coaches and scouts to consider the players’ technical and tactical skills combined with their anthropometric and physiological characteristics scaled to age. Moreover, research addressing the psychological and environmental aspects that influence talent identification and development in football is currently lacking. The limitations detected in the reviewed studies suggest that future research should include the best performers and adopt a longitudinal and multidimensional perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Research addressing the acquisition and development of football expertise has focused on specific key performance characteristics related to practice and training, the performer and the environment. |

This critical review brings to light research evidence uncovering the aspects that are particularly relevant for talent identification and development in football, such as the players’ technical and tactical skills, combined with their anthropometric and physiological characteristics scaled to age. |

We suggest that future research should focus on the technical and physical development of the most talented players worldwide across their entire sport careers. |

1 Introduction

According to official data from the Fédération Internationale de Football (FIFA), 265 million players and 5 million referees and officials are actively involved in the game of football, representing an 4% of the world population [1]. Modern football is characterised by increased movement of players between different countries, and by inflation of wages and transfer fees. In these circumstances, the ability to identify and nurture talented players at an early age may ensure sporting and financial success and/or survival. Accordingly, many football clubs and national federations invest substantial resources into the detection, identification and development of young talented footballers, to ensure that the most promising players receive high-quality coaching and training conditions [2].

Defining the concept of talent is not an easy task and currently there is no consensual definition [3]. Talent is traditionally associated with the notion of an athlete’s precondition for success (e.g. innate potential) and with the outcome of the developmental process (e.g. athletic excellence during youth) [2, 4]. However, across different sports athletes are considered as talented if they perform better than most of their peers or if they are perceived as having the potential to reach the elite level [5]. Based on an ecological dynamics theoretical approach, we argue that talent should be considered as a dynamically varying relationship moulded by the constraints imposed by the physical and social environments, the tasks experienced and the personal resources of a player [6]. The context of modern football is characterised by repeated evaluation of footballers’ potential to succeed at the elite, adult level. Traditionally, there are key stages in the talent identification and development process: (1) talent identification, or the process of recognising and/or selecting current participants with the perceived potential to become elite players; and (2) talent development, whereby players are provided with a suitable learning environment (e.g. amount of practice and specific coach support required at different levels of development) to realise their potential [2, 5, 7]. As stated by Williams and Reilly [2], a crucial question is whether the individual has the potential to benefit from a systematic programme of support and training. In this sense, talent identification should be viewed as a part of the dynamics of the talent development pathway in which identification may occur at various stages within the process. Nevertheless, some authors suggested that reliable early a priori talent identification seems to be impossible [8]. For example, Baker et al. [9] suggested that practitioners “…should not focus so intently on identifying and selecting talent. Scientific evidence suggests that if it does exist, we do not know what it looks like, and are poor predictors of athlete potential” (p. 12).

Over recent years, a growing number of research articles [10–12] have been published about this topic, adding to the various academic books [13, 14], research literature reviews [15–18], specific models of talent development [19–23] and popular books [24]. Also, there has been an increasing emphasis on the use of science-based support systems offering a more holistic approach to talent identification in soccer [25]. Nevertheless, football players were traditionally selected by coaches based on a subjective analysis that recognised the potential of young players to complement the style of play of their club. Depending on the different club philosophies, specific parameters were valued in that selection, such as speed, strength, size and creativity. This was the case despite the scientific evidence showing that unidimensional approaches exclusively favouring biological determinants were ineffective and incapable of predicting adult sport performance [25].

Predicting performance potential at an early age is a difficult and complex process, particularly since the determinants and requirements for success in top-level football are non-linear and multifactorial [12]. The process of talent identification should reflect the long-term development of the player, as short-term success may have associated limitations. Importantly, the specificities of each sport play a critical role in talent identification and development [8]. As argued by Baker et al. [9], effective talent selection requires accurate prediction of the evolutionary tendencies of the specific sport to anticipate how the skills and capabilities underpinning successful performance will evolve between selection and demonstration of elite skill. Indeed, football has changed considerably over the last few decades (see Sarmento et al. [26] for a review) with increased demands on players, a factor that coaches and scouts may wish to consider when selecting talented performers.

Despite the significant expansion in sports talent identification and development research, specific sports have not been addressed individually, including widely practiced sports such as football. Given the specific constraints of each sport, there is a need to consider a sport-specific examination of the factors that could lead to expert performance, rather than search for a generalisable model of athlete development [18]. Thus, systematically reviewing research on football talent identification and development can provide a useful resource for coaches, scouts and scientists. Besides the specificities arising from the evolutionary tendencies of the game, football players’ performance emerges from the interaction of many physical (e.g. strength, power, speed, endurance), technical, tactical and psychological capacities, which in turn are influenced by the specific but dynamic contexts of player cooperation/opposition (11 vs. 11 players) occurring during a 90-min match. Moreover, the varied playing positions in the field (e.g. goalkeeper, defender, midfielder, forward) require the development of specific abilities. Finally, talent identification in football is a dynamic process that is interconnected with the players’ developmental phases [27]. Thus, the process of talent identification and development in football may be influenced by a set of determinants specific to this sport, thereby justifying the search for a contextualised knowledge, rather than relying on general aspects common to several sports [15, 18]. Furthermore, some prudence is required when analysing data from male and female football players due to their maturational, anthropometric, physiological and psychological differences. The dynamics of talent identification and development, the structure of the competitions, the laws of the game [e.g. in some countries before under (U-) age 19 (U-19) level, females can only play formal games of 9 vs. 9], the quality of the coaches and the level of professionalisation are dissimilar across different countries, for males and females.

Nevertheless, the scientific evidence on talent identification and development is not currently advanced enough to truly impact and inform sport practices. Most research has only evaluated single sports in isolation, and findings are extrapolated to other sports, despite the diverse characteristics of different sports. However, developing a systematic review of a single sport [namely in one of the most researched sports (football)] and thus synthesising knowledge about the specificity of talent identification and development in this sport, allows the identification and comparison of similarities as well as key differences between different sports [3].

Thus, to identify and develop the talented football players reliably, it is crucial to determine the skills that better match the specific demands of the game. However, despite the increasing research interest in this topic, the best scientific approaches to successfully identify and develop football players remain unclear. The aim of this article was to systematically review and organise the literature on male football talent identification and development, in order to ascertain the most frequently researched topics, characterise the methodologies and systematise the evolution of the related research trends.

2 Methods

2.1 Search Strategy: Databases and Inclusion Criteria

A systematic review of the available literature was conducted according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) guidelines [28].

To ensure article quality, the electronic databases Web of Science™ Core Collection and Scopus were searched for relevant publications prior to 17 December 2016 by using the keywords “football” and “soccer”. Each of these words was associated with the terms “talent*”, “expert*”, “elite”, “elite athlete”, “identification”, “career transition” or “career progression”. Only empirical articles were included in the search.

The publications included in the first search round met the following criteria: (1) contained relevant data concerning talent identification and/or development; (2) were performed on male footballers; and (3) were written in the English language. Studies were excluded if they (1) included practitioners of other sports; (2) included females; and (3) did not contain any relevant data on talent development.

Two reviewers (HS, AP) independently screened citations and abstracts to identify articles potentially meeting the inclusion criteria. For those articles, full-text versions were retrieved and independently screened by those reviewers to determine whether they met inclusion criteria. Any disagreement regarding study eligibility was resolved in discussions including a third reviewer (MTA). When the decision to include or exclude a given article was not unanimous, the author with greater experience on systematic reviews (MTA) made the final decision.

2.2 Quality of the Studies and Extraction of Data

As recommended in Faber et al. [17], the overall methodological quality of the studies was assessed using the Critical Review Forms in Letts et al. [29] for qualitative studies (counting 21 items) and Law et al. [30] for quantitative studies (counting 16 items).

Each qualitative article was subjected to an objective assessment to determine whether it contained the following 21 critical components: objective (item 1), literature reviewed (item 2), study design (items 3, 4 and 5), sampling (items 6, 7, 8 and 9), data collection (descriptive clarity: items 10, 11 and 12; procedural rigor: item 13), data analyses (analytical rigor: items 14 and 15; auditability: items 16 and 17; theoretical connections: item 18) and overall rigor (item 19) and conclusion/implications (items 20 and 21). Quantitative studies were assessed to determine whether they included the following 16 items: objective (item 1), relevance of background literature (item 2), appropriateness of the study design (item 3), sample included (items 4 and 5), informed consent procedure (item 6), outcome measures (item 7), validity of measures (item 8), significance of results (item 10), analysis (item 11), clinical importance (item 12), description of drop-outs (item 13), conclusion (item 14), practical implications (item 15) and limitations (item 16). Item 9 (details of the intervention procedure) was not applicable because none of the studies included interventions.

The outcomes per item were 1 (meets criteria), 0 (does not meet the criteria fully), or NA (not applicable). The versions of the Critical Review Forms used in this study are shown in Electronic Supplementary Material Tables S1 and S2. A final score expressed as a percentage was calculated for each study by following the scoring guidelines of Faber et al. [17]. This final score corresponded to the sum of every score in a given article divided by the total number of scored items for that specific research design (i.e. 16 or 21 items). We adopted the classifications of Faber et al. [17] and Wierike et al. [31] and classified the articles as (1) low methodological quality—with a score ≤ 50%; (2) good methodological quality—score between 51 and 75%; and (3) excellent methodological quality—with a score > 75%.

A data extraction sheet (from Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group’s data extraction template [32]) was adapted to this review’s study inclusion requirements and then tested on ten randomly selected studies (pilot test). One author extracted the data and another verified it. Disagreements were resolved in discussions between these two authors (HS, AP).

To organise the results, the studies were classified into categories established according to the major research topics that emerged from the content analysis.

3 Results

3.1 Search, Selection and Inclusion of Publications

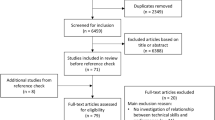

The initial search identified 2944 titles in the aforementioned databases. These data were then exported to reference manager software (EndNote™ X8, Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA). Any duplicates (2325 references) were eliminated either automatically or manually. The remaining 619 articles were then screened for relevance based on their title and abstract, resulting in 479 studies being eliminated from the database. The full text of the remaining 140 articles was examined in more detail; 70 were rejected because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. At the end of the screening procedure, 70 articles were selected for indepth reading and analysis (Fig. 1).

The main factor for study exclusion (n = 36) was their lack of relevance to the research topic of this review. Other studies were excluded because they contained data from female participants (n = 8) or from other sports (n = 26).

The chronological analysis of the articles considered in this review, published no later than the year 2016, evidenced the recent developments in this area of research, highlighting that more than half (55.7%) of the studies were published in the last 5 years (i.e. from years 2012 to 2016).

3.2 Quality of the Studies

Concerning the quality of studies, the most noteworthy results were that (1) the mean score for the 63 selected quantitative studies was 88.5%; (2) the mean score for the seven selected qualitative studies was 86.4%; (3) seven publications achieved the maximum score of 100%; (4) no publication scored below 50%; (5) only three studies scored between 51 and 75%; and (6) 67 publications achieved an overall rating of > 75%.

3.3 General Description of the Studies

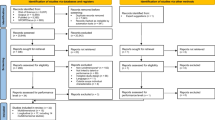

The ecological dynamics theoretical framework argues that the relevant scale for understanding behaviour is the performer–environment dynamic relationship [33], in which the broad range of personal, task and environmental constraints impacts on athletes’ development according to different, related, timescales [6]. As proposed by Davids and colleagues [6], skill acquisition, expert performance and talent development in sport should consider both the macro- and the micro-structure of contextualised histories and practices. Based on this theoretical rationale, after careful analysis, it was decided that the most appropriate way to present the results would be to categorise them according to the major research topics that emerged from the analysis. Although a few studies were markedly multidimensional [34–36], the generality were focused on a single topic as follows: (1) task constraints: (a) specificity and volume of practice; (2) performers’ constraints: (a) psychological factors; (b) technical and tactical skills; (c) anthropometric and physiological factors (compared according to competitive level, playing positions and birth month); (3) environmental constraints: (a) relative age effect; (b) socio-cultural influences; and (4) multidimensional analysis (Fig. 2).

3.3.1 Task Constraints

3.3.1.1 Specificity and Amount of Football-Specific Practice

The relationship between the amount of time spent in activities specifically designed to improve performance (deliberate practice) and a player’s level of achievement is well-documented [21, 37, 38]. Recent research indicates that early engagement (6–12 years) in football (i.e. play and practice) may be associated with higher levels of expertise (Table 1).

3.3.2 Performers’ Constraints

3.3.2.1 Psychological Factors

Sports research has developed heuristic models that provide valuable information about the pathways and profiles associated with success [20, 21, 39–42]. Nevertheless, only a relatively small number of papers have addressed these topics exclusively in the context of football, the most popular sport in the world (see Table 2) [43–48]. These investigations have focused mainly on the study of motivation [44, 48], stress and coping [45, 47], discipline [43], resilience [43], commitment [43], social support [43, 45, 47] and concentration [44], providing some information about the psychological factors that are associated with career success [44, 47]. The most successful players seem to express higher levels of resilience, confidence, concentration, commitment, discipline, motivation, mental rehearsal and coping with adversity [43–48].

3.3.2.2 Technical and Tactical Skills

Although the process of selection of talents in football is influenced by a wide range of factors, the most prominent aspect evaluated by coaches and scouts is technical ability, as this is believed to be a strong predictor of performance. This is shown in several studies (Table 3) demonstrating that superior technical skills, such as dribbling [49, 50], short/long passing and kicking at the goal [50], provide relevant information for talent identification systems. Additionally, evaluation of basic sprinting and dribbling activities [51] in youth soccer can assist practitioners developing training programmes. With respect to tactical skills, positional skills and decision-making are the best predictors of the performance level in adult elite performers [52]. Also, the more skilled players (i.e. from the Dutch national youth soccer team) seem to outperform the less skilled players (i.e. from the Indonesian national youth soccer team) based on their declarative (knowing what to do) and procedural (doing it) knowledge [87].

3.3.2.3 Anthropometric and Physiological Factors

Anthropometric and physiological factors have been extensively studied in the context of talent identification and development in football. The reviewed research has sought to establish ‘profiles’ that characterise the most talented players in different phases of their development according to their competitive level, playing positions and birth month. Most studies investigated the influence of anthropometric and physiological factors on football talent in relation to the competitive level achieved by the players; however, because different research strategies were adopted to classify those competitive levels, it becomes difficult to find clear associations (Table 4). Nevertheless, the reviewed studies showed that key morphological and functional capabilities (muscular power, agility, coordination, speed and endurance) seem to discriminate players already selected and exposed to systematic training and may provide a basis for employing more clear criteria in respect to player identification and development [53]. However, for this information to be reliable, the athlete’s biological age or biological maturity should be considered [54]. This body of research offers some suggestions for developing training programmes such as match-running performance [11] and explosive power [55].

3.3.3 Environmental Constraints

3.3.3.1 Relative Age Effect

Over the last three decades, it has been demonstrated in a number of sports that a player’s relative age is associated with talent selection, as individuals born in the first months of a year are generally more widely represented. Indeed, individuals born early in the year may be almost a year older than those born later in the same year, even though they will be competing in the same sport task, and they are therefore more likely to be selected. This advantage of being born early within a cohort has been named the ‘relative age effect’ (RAE) or ‘birth date effect’. This review highlighted a consensus in the literature as to the over-representation of football players born in the first months of the year (Table 5) in several European countries (e.g. Belgium, England, Spain, Germany, Portugal, Italy) [4, 12, 56–68] and FIFA designated zones [69]. Studies analysing a potential link between playing positions and RAE produced conflicting results. It was first shown that European professional players in all playing positions (goalkeeper, defender, midfielder and forward) were equally affected by RAE [69]. In agreement with this study, no relationship was found between RAE and playing position in youth teams playing in the Spanish Professional League [61]. However, another study showed that RAE may be a predictor of playing positions in Swiss national teams [65]. These studies show that talent identification in football can be significantly affected by RAE.

3.3.3.2 Socio-Cultural Influences

Despite the significant influence of the social environment on the development of young athletes, few studies have addressed this issue exclusively in the context of football. Furthermore, it is important to note that nearly all of these studies were qualitative (Table 6). Supportive environments for soccer development seem to have different priorities: (1) social influences and organisational culture during the games and training sessions; and (2) compatibility of the sports practice with familiar, social and school contexts. Furthermore, coaches and players disagreed on the importance of different factors [70] and clubs do not use the existing literature to improve their practices [71].

3.3.4 Multidimensional Analysis

While most studies in this research area focused mainly on a single topic, a group of multidimensional studies (Table 7) investigated the impact of a variety of factors on talent identification and development, including technical, tactical, physiological, anthropometric and psychological factors (see Fig. 2). Given the specific nature and scarcity of these studies, these are discussed in the relevant subsections of Sect. 4.

4 Discussion

The aim of this article was to review the available literature on talent identification and development of male footballers. The results showed an incremental interest in this research topic over the years (see Sect. 3.1). In the following sections we discuss some of the most interesting results emerging from the analyses performed in this review, based on an ecological dynamics theoretical framework.

4.1 Task Constraints

4.1.1 Specificity and Amount of Football-Specific Practice

Understanding what facilitates engagement and effectiveness in sports practice may contribute to the development and implementation of effective programmes [18]. A widely held view is that 10,000 h of deliberate practice (highly structured activity with the specific goal of improving performance, which requires effort and is not inherently enjoyable [21]) are necessary and sufficient to reach expert level, as initially suggested by Chase and Simon [72]. However, there is considerable variation in these figures within and across sports, with some data suggesting that there are significant differences among sports in the average amount of practice time required to progress from novice to senior national representation [15]. Due to the inherent non-linearities in human development, the amount of time needed to achieve an expert level cannot be precisely specified [6]. Nevertheless, recent research indicates that the number of accumulated hours spent in football-specific team practice at early ages (6–12 years) is associated with higher levels of expertise in English [73–76], Swiss [77], German [78] and Norwegian [79] football players. The overall conclusion is that specific practice is relevant, but the quantity that is needed cannot be predicted in advance due its interaction with other constraints.

The potential benefits of being involved in enjoyable activities related to a specific sport during childhood have been extensively discussed by the scientific community [18]. The studies reviewed here support the idea that involvement in deliberate football-specific play activities per se is not an important correlate of expertise; however, at early ages (6–15 years), an optimal balance between deliberate practice and deliberate play (early developmental activities, specifically designed to maximise enjoyment, and which are intrinsically motivating and provide immediate gratification [80]) appears to be related to higher levels of expertise [37, 38, 73, 74]. Indeed, a greater number of hours accumulated per year in practice or football-specific play activity during childhood [76, 81], or between 14 and 18 years old [75], was a strong predictor of perceptual–cognitive expertise in football-related tasks. Additionally, evidence from different sports demonstrated that early specialisation is not the only pathway to reaching high levels of expertise. It seems that early diversification can also lead to elite performance (see Coutinho et al. [18] for a review), especially in sports where the peak performance is achieved after biological maturity [15]. However, playing other sports in addition to football at a young age does not have a significant influence on the level of expertise achieved in football [73–75, 82]. These two contrasting development pathway patterns (early specialisation and early diversification) have been discussed extensively in the literature [6]. Nonetheless, the characterisation of past sport experiences based on footballers’ perceptions is somewhat restricted, thus highlighting the need for longitudinal studies integrating macro-structural approaches (e.g. deliberate practice) with theoretical ideas concerning the micro-structure of different learning activities [6, 18]. For this, future research on footballers’ retrospective reports should be complemented with real-time systematic observation of players’ practice and play activities [18].

Future investigation about task constraints in football may also consider, for instance, the impact of rule manipulation, boundary locations and equipment (scaled to the players’ morphology).

4.2 Performers’ Constraints

4.2.1 Psychological Factors

The influence of psychological factors on sports performance is well-established; however, research on the role they may play on football talent identification and development is scarce. Moreover, studies addressing the psychological characteristics of talented football players vary widely in research design (interviews vs. questionnaires), player performance level (elite, sub-elite and regional players), sample size and analysed psychological skills. Thus, the interpretation of those data remains challenging. Nevertheless, investigation of psychological factors related to high performance tends to address two main questions: (1) which psychological skills are needed to reach top performance?; and (2) how can these skills be developed in young talents? [83]. The reviewed studies suggest that the most successful athletes express high levels of goal commitment, engagement in problem-focused coping behaviours [47], discipline, resilience [43], mental rehearsal, concentration, peaking under pressure, achievement motivation [44], effort [45, 46] and self-regulation [46]. These findings are useful for monitoring improvements in training and game performance and for identifying the necessary changes in practice regimens [46]. Additionally, accurate diagnosis of the role of psychological factors in athletes who are not making the expected career progress can be useful in the design of specific development programmes [43]. Nevertheless, little is known about training of motivational and self-regulatory skills as well as how these skills change across different phases of player development. From an ecological perspective [84, 85], it makes no sense to perceive psychological skills as inner, independent and stable features of the individual. In contrast, practitioners and sport scientists may perceive these competencies as socially supported and dependent on the specific environmental circumstances. Thus, further research is needed to better understand this complex relationship across different organisational cultures. Additionally, greater knowledge of the psychological skills specific to different playing positions may contribute to a better understanding of their importance on talent identification and development.

4.2.2 Technical and Tactical Skills

Although few studies have addressed the importance of technical and tactical skills for talent identification and development in football, there is a clear association between high achievement and superior technical skills, including dribbling, short/long pass, ball retention and shooting [34–36, 49, 50, 86]. For instance, research suggests that players with superior dribbling skills in their teens become high performers as adults [51]. The complex relationship between the factors (advanced age, lean body mass, hours of practice, playing position) that predict dribble performance deserves more research to improve trainers’ and coaches’ understanding of performance development [50].

Tactical skills refer to the quality of an individual player to perform a timely action [52] that is effective for achieving a task goal. A study of German young players highlights the relevance of tactical skills for a successful high-profile career in football [52, 87]. Thus, development of tactical skills seems crucial for achieving top-level performance in football. However, how to implement effective strategies that develop technical and tactical skills in footballers is not clear. For this, the ecological dynamics approach can offer theoretical guidance for coaches, sport scientists and practitioners to carefully design the micro-structure of practice environments through manipulations of task constraints [6]. The precise micro-structure of practice needs to simulate relevant and effective solutions demanded in dynamic competitive environments. Nevertheless, the constant evolution of football (playing systems, laws of the game, etc.) requires continuous adaptations to changing task and environmental constraints, shaping skill performance and enhancing the non-linearity of the relationship between the game and players as complex adaptive systems [6]. An interesting example emerges from most recent rule changes (back pass and 6 s release rules) that have imposed new requirements for goalkeepers during match play, namely taking active part in attacking play, assuming the role of a ‘libero’ in the defensive phase, and developing goalkeepers’ skills of controlling and passing the ball with their feet. Despite this significant change, football goalkeepers were often ignored in the reviewed studies.

4.2.3 Anthropometric and Physiological Factors and Multidimensional Analysis

There are some differences in anthropometric and physiological traits between successful and less successful youth football players; however, variations in biological maturation may affect player identification based on those factors. Thus, longitudinal studies with multidimensional evaluations are necessary to reveal pathways to high levels of expertise [55, 88, 89].

Overall, studies analysing the influence of anthropometric and physiological factors on talent identification reveal that elite players score better in tests measuring strength [90, 91], flexibility [90], coordination [92], agility [92, 93], speed [55, 90, 91, 93–95], football-specific speed [91], aerobic endurance [90, 93, 95], anaerobic capacity [90] and several technical skills [90]. The most successful players are often also taller [94] and leaner [36, 94]. Moreover, speed is associated with player selection at the ages of 10–14 [94, 96] and 16 years old [95], while agility and coordination are associated with future success in 11-year-old players [92]. Successful U-15 and U-16 players have greater aerobic endurance [90, 96].

Similar anthropometric and physiological analyses, but which also considered the players’ field positions, showed that goalkeepers, defenders [88, 97, 98] and central strikers [97] were taller, heavier and older than players based in central and wider positions [88, 97]. Moreover, midfielders and players in wider positions had a lower body mass index and reciprocal ponderal index than central players [97], and goalkeepers had more body fat and performed worse in physical tests than outfield players [99]. Whilst the physical advantages of goalkeepers and central defenders might be envisaged in competitive match-play scenarios, they were not evident in the physical fitness tests (agility, sprinting and endurance). Lateral midfielders seem to be faster sprinters than central midfielders at U-15/U-16 (small effect), and this difference is greater at U-17/U-18 [97]. Towlson et al. [98] suggested that such variation, observed before the peak height velocity, may reflect the development of position-specific physical attributes, and not necessarily an identification phenomenon. In turn, Coelho e Silva et al. [100] showed that variations in several anthropometric and physiological traits according to field position were negligible in Portuguese footballers, except for the ‘ego orientation’ psychological variable. Indeed, midfielders had higher ego orientation than defenders and forward players. In addition, in every field position, the most successful players (selected as regional players) were heavier, taller and showed more advanced skeletal maturation. Nevertheless, the inter-individual paths of biological maturation are more flexible than what is demanded for playing position allocation [98]. Coaches and scouts may need to include an estimation of years to peak height velocity for an individualised training prescription [55].

Analysis of secular changes in body size, shape and age characteristics in the top English League (from 1973/1974 to 2003/2004) showed that professional players were taller (by a mean 1.2 cm) and heavier (by a mean 1.29 kg) each decade. When compared with less successful teams, players from successful teams (top six) were found to be taller, leaner (as identified by a greater reciprocal ponderal index and ectomorphy score) and younger, a characteristic that was most marked for forwards [101]. Despite these findings Carling et al. [101] demonstrated that size, maturity and functional characteristics remained unchanged over 15 years (from 1992/1993 to 2002/2003) in young players who were selected for elite sport academies and reached professional level. These authors suggested that there may have been a lack of change in selection philosophies in the identification practices of coaches and scouts across the studied period.

Recent research has addressed the relationships between birth month and anthropometry, biological maturity and physical fitness in younger footballers [54, 102–104]. As mentioned in Sect. 4.1, overall there are more players born in the first quarter (Q1) than in the last (Q4), suggesting that the former have a selection advantage because, in general, they reach biological maturity earlier [54, 102–104]. Consistent with this assumption, players born in Q4 were significantly smaller than those born in Q1 (U-11, U-13 and U-14 categories) when maturation differences were controlled for statistically [103]. Moreover, Fragoso et al. [54] showed in a study of 133 Portuguese elite football players (U-15) that players born in Q1 had a fitness advantage (sprint time and squat jump). However, Deprez et al. [102] found no differences in height, weight (except for U-15) or any anaerobic parameter between players born in different birth quarters (374 Belgian players, U-13 to U-17). In addition, a study of 332 Japanese players (U-10 to U-15) revealed no significant maturation disparities between players born in different birth quarters for any age category [103]. Nevertheless, studies of Belgian [102] and English [104] youth football players concluded that the relatively older footballers had an increased likelihood of being selected [102, 104] with a particular strong RAE bias observed in the U-9 and U-13/U-16 squads [104]. This was independent of their maturity status, whereas relatively younger footballers had a chance of selection only if they were early maturing [102, 104]. A longitudinal study by Ostojic and colleagues [89] showed that significantly more late-maturing players reached elite level in adult football than early-maturing players, suggesting that player selection favours late-maturing footballers as level of performance increases. The reduced percentage of later-maturing players selected for academies highlights a need for players’ evaluation beyond immediate performance. Late-maturing youth may need to be nurtured until maturity is attained [105] and this presents a challenge for those involved in making early selection decisions [101]. Nonetheless, the reviewed research demonstrates some disadvantages when identifying the ways by which footballers in different quartiles are similar in respect to relevant football-specific constraints. For this, a person-oriented analysis could be a useful direction for future research instead of a variable-oriented analysis (see Wattie et al. [106] for a review).

The empirical and theoretical literature shows that identification of specific performance characteristics for a development programme, supported by appropriate procedures to follow and recapture late maturers, offers sports clubs a clearer picture of the type of characteristics (technical, tactical, anthropometrical, physiological) they can identify and develop in the young players [35].

4.2.4 Genetic Factors

The reviewed scientific evidence concerning performers’ constraints (Sects. 4.2.1, 4.2.2 and 4.2.3) demonstrated that one of the most debated topics in this area of research, namely the genetic influence, has not been studied in football players.

4.3 Environmental Constraints

4.3.1 Relative Age Effect

From an ecological dynamics approach [106, 107], different categories of constraints (individual, environmental, task) can be considered in a development systems model for RAEs. The influence of a player’s RAE on talent identification has been extensively studied in football; however, as identified by Wattie and colleagues [106] for the generality of sports, the main body of the reviewed research has been de-contextualised with respect to the broader characteristics of footballers’ developmental ecology. Several studies have reported this effect in players from Belgium [4, 56, 58, 63], England [4, 57, 63], Spain [4, 59–61], Germany [4, 12, 62–64, 66], Switzerland [65], and Portugal, Netherlands, France, Italy, Denmark and Sweden [4, 63]. These studies show that talent identification in football can be significantly affected by RAE, because coaches and scouts select those players who are the best performers at the time of selection, rather than the most promising players in the long-term. The pressure on some clubs and coaches to obtain immediate results, even with young players, favours the selection of footballers who are more likely to succeed in the short-term due to their age (months) advantage, thus compromising the selection of players with greater potential in the long-term. Almost 20 years ago, Helsen et al. [56] showed that players born in the early months of the selection year (6–8 years age group) were more likely to be exposed to more (and better) coaching, while players born later in that year had higher probability of dropping out, at as early as 12 years of age. More recently, Skorski and colleagues [12] demonstrated that players born in the last birth quarter of the selection year were more likely to become professional players than those born in the first birth quarter. Moreover, this study also showed that RAE cannot be explained by anthropometric or performance-related parameters. Interestingly, this early-birth selection bias was perpetuated over the years in a ‘cascade effect’, as being selected at an early age increased the players’ chances of being selected in subsequent years in youth football in England [60, 65], and this effect remained even when body mass was normalised [57]. However, Gonzalez-Villora et al. [67] showed that RAE is less significant at the professional level than in youth elite levels, in particular U-17.

The RAE has been explained based on cognitive and physical maturation. Athletes who were born earlier (relatively older athletes) in the selection year had significant advantages when compared with those who were chronologically younger (relatively younger athletes) [102], which could be explained by explanation the maturational differences between them. Nevertheless, the reviewed studies [12, 102, 103] suggest that players born later in the selection year but with advanced biological maturity, resulting in better performance, tend to be selected for elite teams (see Sect. 4.2.3 for more details). Studies analysing the link between playing positions and RAE present conflicting results and fail to clarify whether RAE influences the playing position when at the adult level. According to Wattie et al. [106], the reviewed literature has focused on some individual (birth date, physical maturation and size), task (participation level, playing position) and environmental (age grouping policies) constraints, revealing the need to investigate other types of constraints, such as the popularity of sport, family and coach influences, training time and laterality advantage. This micro-level approach could also be used to test the efficacy of the specific policies which have been proposed to limit the negative effect of relative age on talent identification: (1) design calendars with alternative age limits of selection [4]; (2) create more age categories with smaller bandwidth [4]; (3) divide players into categories according to skill level; and (4) allow players born later in the year to temporarily change to a younger age category [67].

In addition, studying the simultaneous influence of multiple constraints, possibly from multiple sources and from multiple research methods (qualitative and quantitative) [106], for the understanding of the RAE in football is warranted.

4.3.2 Socio-Cultural Influences

While it is well-accepted that several environmental factors influence the development of young athletes [39, 108], few studies have addressed this topic exclusively in the context of football. Moreover, these studies were performed mainly in English [10, 70, 71, 109–111] and Swedish [112] clubs. Horrocks et al. [10] reported that consistent high-level performers in an English club developed intensive individualistic developmental behaviours and routines that were encouraged by the club. However, Morley et al. [70] found that players and coaches may have diverging priorities concerning the key aspects of player development. For instance, game and training were considered essential for player development by both players and coaches, but no consensus could be obtained on the relative importance of aspects concerning personal and social life, school and lifestyle. ‘Discipline’ emerged as a prominent feature of player development.

Mills et al. [109, 110] highlighted the importance of establishing well-integrated youth and senior teams, positive working relationships with parents, and strong and dynamic organisational cultures at elite youth football academies. Although academies seemed helpful in specific areas related to coaching, organisation and sport-related support, areas related to athlete understanding and links to senior progression were perceived less favourably. The authors therefore suggested that academies should pay close attention to the psychosocial environments they create for developing players. Morley et al. [70] analysed two operational youth-to-senior transition programmes in professional football and the factors that may influence transition outcomes. The data suggested that a proactive intervention programme targeting demands, barriers and resources associated with transition may be beneficial for the development of youth athletes and club success, both in terms of reputation and finance.

Interestingly, Ivarsson et al. [112] found that Swedish players (13–16 years old) who perceived the environment for their talent development as supporting and focused on long-term development were less stressed and experienced greater well-being than other players. A study by Pazo et al. [113] performed with talented Spanish players proposed that sport context is among the most influential dimensions in the training process of a football player. Moreover, training in an elite academy is key for achieving success in football. Finally, the coordination between all staff members in a football academy, such as psychologists, doctors, fitness coaches and directors, also seemed relevant for the players’ personal development.

Deep understanding of the broader development context, through an ecological dynamics approach [114], can be fruitful for identifying (and promoting) optimal environments for talent development. According to an ecological dynamics approach, footballers and their contexts of practice are adaptive systems that need to be understood at an irreducible level of analysis: that of the performer–environmental relationship. In this view, talent has been conceptualised as an enhanced and functional relationship developed between a performer and a specific performance environment [6]. The studies reviewed in the present work reveal a lack of investigation into the design of the practice micro-structure over time in youth football practice (see Sect. 4.2.2). Additionally, greater understanding of the influence of the family (parents, siblings) in talent development, namely what support parents can offer to their children as footballers and how parents can support football players as they move across key transition points in their sport career, is required [115]. At the macro-structure level, more attention may be given to the management of school activities and those of the football club. Football federations may potentially want to consider which everyday school activities are conducive to the talent development process.

4.3.3 Other Factors

In addition to the reviewed topics (RAE and socio-cultural influences), studies of environmental constraints need to address many other constraints such as physical environments (e.g. playing in the sand, dirt-field, grass [8]), climatic conditions (e.g. temperature, humidity) and geographic constraints (e.g. altitude).

4.4 Limitations

A possible limitation of this systematic review is that it only includes studies in English from the Web of Science™ Core Collection and Scopus databases, thereby potentially overlooking other relevant publications. Additionally, the inclusion of a panel of experts after electronic database searching who suggest more articles that align with the inclusion criteria may be a useful future step.

5 Conclusion

Over recent years, there has been growing research interest in youth player talent development and identification in football. The considerable number of studies reviewed here allowed the identification of the most frequently addressed topics in this research area: (1) task constraints: (a) specificity and volume of practice; (2) performers’ constraints: (a) psychological factors; (b) technical and tactical skills; (c) anthropometric and physiological factors; (3) environmental constraints: (a) RAE; (b) socio-cultural influences; and (4) multidimensional analysis (Fig. 2).

The definition of talent is not consensual across different sports and scientific disciplines (see Sect. 1). Some authors [3] raise the difficulty of an operational definition of talent, given the continuous evolution of performances, scientific procedures and sport rules. One of the possible ways that could be used to explore a domain-specific operational definition of talent would be through the publication of systematic reviews [3]. Indeed, the reviewed evidence indicated that the most talented players tend to be heavier, taller, showed more advanced skeletal maturation and scored better in tests measuring strength, flexibility, coordination, agility, speed, aerobic and anaerobic capacity, technical (e.g. dribbling, short/long passing, maintaining ball possession, shooting) and tactical skills. In regards to the psychological competencies, talented players seem to express higher levels of motivation, confidence, concentration, commitment, discipline, mental rehearsal, resilience and coping with adversity. It seems that coaches and scouts could avoid the negative influence of the RAE on talent selection by being aware of the impact of physical and biological maturation on immediate performance and not discriminating against younger or late-maturing players.

The reviewed literature highlighted that there is a complex relationship between the tactical, technical, anthropometric, maturational, physiological and psychological factors according to each age, maturational status and specific playing positions. This complex interaction should be carefully considered by those involved in the process of identification and development of talented football players. Moreover, an optimal balance between specialisation (e.g. deliberate practice) and diversification (e.g. deliberate play) appears to be related to higher levels of performance at both early ages and adulthood. Finally, close attention should be paid to the supportive psychosocial environments created in the sport academies for developing players. Overall, talent identification and development programmes in football must be dynamic, providing opportunities for changing evaluation parameters in the long-term.

We found several limitations in the available literature. First, there is currently a need for more longitudinal studies following the entire career path of the most successful players. Second, research addressing the influence of genetic factors in elite athletic status is lacking. Third, goalkeepers are excluded from many studies and few studies included the most talented footballers. Another research gap identified in this review was a multidimensional analysis of how different elements interact to influence talent identification and development in football. Moreover, reviews offering an overview of the literature are also lacking. Finally, there is a need for more research on the psychological and environmental aspects impacting talent development in football.

References

FIFA. 265 million playing football. FIFA Magazine 2006. https://www.fifa.com/mm/document/fifafacts/bcoffsurv/emaga_9384_10704.pdf.

Williams AM, Reilly T. Talent identification and development in soccer. J Sports Sci. 2000;18(9):657–67.

Schorer J, Wattie N, Cobley S, et al. Concluding, but definitely not conclusive, remarks on talent identification and development. In: Baker J, Cobley S, Schorer J, Wattie N, editors. Routledge handbook of talent identification and development in sport. London: Routledge; 2017. p. 466–76.

Helsen W, Van Winckel J, Williams A. The relative age effect in youth soccer across Europe. J Sports Sci. 2005;23(6):629–36.

Schorer J, Elferink-Gemser M. How good are we at predicting athletes futures? In: Farrow D, Baker J, MacMahon C, editors. Developing sport expertise: researchers and coaches put theory into pratice. Oxon: Routledge; 2013.

Davids K, Gullich A, Shuttleworth R, et al. Understanding environmental and task constraints on talent development. In: Baker J, Cobley S, Schorer J, Wattie N, editors. Routledge handbook of talent identification and development in sport. London: Routledge; 2017. p. 192–206.

Baker J, Cobley S, Schorer J, et al. Talent identification and development in sport. In: Baker J, Cobley S, Schorer J, Wattie N, editors. Routledge handbook of talent identification and development in sport. London: Routledge; 2017. p. 1–8.

Araújo D, Fonseca C, Davids K, et al. The role of ecological constraints on expertise development. Talent Dev Excell. 2010;2(2):165–79.

Baker J, Schorer J, Wattie N. Compromising talent: issues in identifying and selecting talent in sport. Quest. 2017;1–16.

Horrocks DE, McKenna J, Whitehead A, et al. Qualitative perspectives on how Manchester United Football Club developed and sustained serial winning. Int J Sports Sci Coach. 2016;11(4):467–77.

Saward C, Morris JG, Nevill ME, et al. Longitudinal development of match-running performance in elite male youth soccer players. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016;26(8):933–42.

Skorski S, Skorski S, Faude O, et al. The relative age effect in elite German youth soccer: implications for a successful career. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2016;11(3):370–6.

Farrow D, Baker J, MacMahon C. Developing sport expertise: researchers and coaches put theory into pratice. 2nd ed. Oxon: Routledge; 2013.

Baker J, Cobley S, Schorer J, et al. Routledge handbook of talent identification and development in sport. London: Routledge; 2017.

Rees T, Hardy L, Güllich A, et al. The Great British medalists project: a review of current knowledge on the development of the world’s best sporting talent. Sports Med. 2016;46(8):1041–58.

Cobley S, Baker J, Wattie N, et al. Annual age-grouping and athlete development: a meta-analytical review of relative age effects in sport. Sports Med. 2009;39(3):235–56.

Faber IR, Bustin PM, Oosterveld FG, et al. Assessing personal talent determinants in young racquet sport players: a systematic review. J Sports Sci. 2016;34(5):395–410.

Coutinho P, Mesquita I, Fonseca AM. Talent development in sport: a critical review of pathways to expert performance. Int J Sports Sci Coach. 2016;11(2):279–93.

Cote J, Fraser-Thomas J, Jones E. Play, practice and athlete development. In: Farrow D, editor. Developing sport expertise: researchers and coaches put theory into practice. London: Routledge; 2008. p. 17–28.

Gagné F. Transforming gifts into talents: the DMGT as a development theory. High Abil Stud. 2004;15:119–47.

Erickson A, Krampe R, Tesch-Römer C. The role of deliberate pratice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol Rev. 1993;100:273–305.

Stambulova N. Development sports career investigations in Russia: a post-perestroika analysis. Sport Psychol. 1994;8:221–37.

Wylleman P, Lavalee D, Alferman D. Career transitions in competitive sport. Biel: Fédération Européene de psychologie du sport et des activités corporelles; 1999.

Epstein D. The sports gene - inside the science of extraordinary athletic performance. New York: Penguin Group; 2013.

Unnithan V, White J, Georgiou A, et al. Talent identification in youth soccer. J Sports Sci. 2012;30(15):1719–26.

Sarmento H, Marcelino R, Anguera M, et al. Match analysis in football: a systematic review. J Sports Sci. 2014;32:1831–43.

Vaeyens R, Lenoir M, Williams AM, et al. Talent identification and development programmes in sport : current models and future directions. Sports Med. 2008;38(9):703–14.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Letts L, Wilkins S, Stewart D, et al. Critical review form: qualitative studies (version 2.0). Hamilton: MacMaster University; 2007.

Law M, Stewart D, Pollock N, et al. Critical review form: quantitative studies. Hamilton: MacMaster University; 1998.

Wierike S, Van der Sluis A, Van den Akker-Scheek I, et al. Psychosocial factors influencing the recovery of athletes with anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2013;23(5):527–40.

Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group. Data extraction template for included studies. 2016. http://cccrg.cochrane.org/author-resources. Accessed 10 Jan 2017.

Davids K, Araújo D, Vilar L, et al. An ecological dynamics approach to skill acquisition: implications for development of talent in sport. Talent Dev Excell. 2013;5(1):21–34.

Forsman H, Blomqvist M, Davids K, et al. Identifying technical, physiological, tactical and psychological characteristics that contribute to career progression in soccer. Int J Sports Sci Coach. 2016;11(4):505–13.

Huijgen BC, Elferink-Gemser MT, Lemmink KA, et al. Multidimensional performance characteristics in selected and deselected talented soccer players. Eur J Sport Sci. 2014;14(1):2–10.

Reilly T, Williams AM, Nevill A, et al. A multidisciplinary approach to talent identification in soccer. J Sports Sci. 2000;18(9):695–702.

Côté J, Hay J. involvement in sport: a developmental perspective. In: Silva J, Stevens D, editors. Psychological foundations of sport. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2002. p. 484–502.

Baker J, Horton S, Robertson-Wilson J, et al. Nurturing sport expertise: factors influencing the development of elite athlete. J Sports Sci Med. 2003;2:1–9.

Côté J. The influence of the family in the development of talent in sport. Sport Psychol. 1999;13(4):395–417.

Côté J. Opportunities and pathways for beginners to elite to ensure optimum and lifelong involvement in sport. In: Hooper S, Macdonald D, Phillips M, editors. Junior sport matters: briefing papers for Australian junior sport. Belconnen: Australian Sports Commission; 2007. p. 20–8.

Côté J. Pathways to expertise in team sport. In: Nascimento J, Ramos V, Tavares F, editors. Jogos desportivos: formação e investigação. Florianópolis: Universidade do estado de Santa Catarina; 2013. p. 59–78.

Erickson K. The road to excellence: the acquisition of expert performance in the arts and sciences, sports, and games. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996.

Holt N, Dunn J. Toward a grounded theory of the psychosocial competencies and environmental conditions associated with soccer success. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2004;16(3):199–219.

Coetzee B, Grobbelaar H, Gird C. Sport psychological skills that distinguish successful from less successful soccer teams. J Hum Mov Stud. 2006;51(6):383–401.

Holt N, Mitchell T. Talent development in English professional soccer. Int J Sport Psychol. 2006;37(2–3):77–98.

Toering T, Elferink-Gemser M, Jordet G, et al. Self-regulation and performance level of elite and non-elite youth soccer players. J Sports Sci. 2009;27(14):1509–17.

Van Yperen N. Why some make it and others do not: identifying psychological factors that predict career success in professional adult soccer. Sport Psychol. 2009;23(3):317–29.

Zuber C, Zibung M, Conzelmann A. Motivational patterns as an instrument for predicting success in promising young football players. J Sports Sci. 2015;33(2):160–8.

Huijgen B, Elferink-Gemser M, Post W, et al. Soccer skill development in professionals. Int J Sports Med. 2009;30(8):585–91.

Waldron M, Worsfold P. Differences in the game specific skills of elite and sub-elite youth football players: implications for talent identification. Int J Perform Anal Sport. 2010;10(1):9–24.

Huijgen B, Elferink-Gemser M, Post W, et al. Development of dribbling in talented youth soccer players aged 12–19 years: a longitudinal study. J Sports Sci. 2010;28(7):689–98.

Kannekens R, Elferink-Gemser M, Visscher C. Positioning and deciding: key factors for talent development in soccer. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21(6):846–52.

Le Gall F, Carling C, Williams M, et al. Anthropometric and fitness characteristics of international, professional and amateur male graduate soccer players from an elite youth academy. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13(1):90–5.

Fragoso I, Massuca LM, Ferreira J. Effect of birth month on physical fitness of soccer players (under-15) according to biological maturity. Int J Sports Med. 2015;36(1):16–21.

Deprez D, Fransen J, Lenoir M, et al. A retrospective study on anthropometrical, physical fitness, and motor coordination characteristics that influence dropout, contract status, and first-team playing time in high-level soccer players aged eight to eighteen years. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(6):1692–704.

Helsen W, Starkes J, Van Winckel J. The influence of relative age on success and dropout in male soccer players. Am J Hum Biol. 1998;10(6):791–8.

Simmons C, Paull GC. Season-of-birth bias in association football. J Sports Sci. 2001;19(9):677–86.

Vaeyens R, Philippaerts RM, Malina RM. The relative age effect in soccer: a match-related perspective. J Sports Sci. 2005;23(7):747–56.

Jimenez IP, Pain MTG. Relative age effect in Spanish association football: its extent and implications for wasted potential. J Sports Sci. 2008;26(10):995–1003.

Mujika I, Vaeyens R, Matthys SPJ, et al. The relative age effect in a professional football club setting. J Sports Sci. 2009;27(11):1153–8.

Gutierrez D, Pastor J, Gonzalez S, et al. The relative age effect in youth soccer players from Spain. J Sports Sci Med. 2010;9(2):190–8.

Augste C, Lames M. The relative age effect and success in German elite U-17 soccer teams. J Sports Sci. 2011;29(9):983–7.

Helsen W, Baker J, Michiels S, et al. The relative age effect in European professional soccer: did ten years of research make any difference? J Sports Sci. 2012;30(15):1665–71.

Toering T, Elferink-Gemser MT, Jordet G, et al. Self-regulation of learning and performance level of elite youth soccer players. Int J Sport Psychol. 2012;43(4):312–25.

Romann M, Fuchslocher J. Relative age effects in Swiss junior soccer and their relationship with playing position. Eur J Sport Sci. 2013;13(4):356–63.

Votteler A, Höner O. The relative age effect in the German football TID programme: biases in motor performance diagnostics and effects on single motor abilities and skills in groups of selected players. Eur J Sport Sci. 2014;14(5):433–42.

Gonzalez-Villora S, Pastor-Vicedo JC, Cordente D. Relative age effect in UEFA championship soccer players. J Hum Kinet. 2015;47(1):237–48.

Sæther SA. Selecting players for youth national teams-a question of birth month and reselection? Sci Sports. 2015;30(6):314–20.

Padron-Cabo A, Rey E, Garcia-Soidan JL, et al. Large scale analysis of relative age effect on professional soccer players in FIFA designated zones. Int J Perform Anal Sport. 2016;16(1):332–46.

Morley D, Morgan G, McKenna J, et al. Developmental contexts and features of elite academy football players: coach and player perspectives. Int J Sports Sci Coach. 2014;9(1):217–32.

Morris R, Tod D, Oliver E. An analysis of organizational structure and transition outcomes in the youth-to-senior professional soccer transition. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2015;27(2):216–34.

Chase W, Simon H. The mind’s eye in chess. In: Chase W, editor. Visual information processing. New York: Academic Press; 1973.

Ford P, Ward P, Hodges N, et al. The role of deliberate practice and play in career progression in sport: the early engagement hypothesis. High Abil Stud. 2009;20(1):65–75.

Ford PR, Williams AM. The developmental activities engaged in by elite youth soccer players who progressed to professional status compared to those who did not. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2012;13(3):349–52.

Ward P, Hodges NJ, Starkes JL, et al. The road to excellence: deliberate practice and the development of expertise. High Abil Stud. 2007;18(2):119–53.

Roca A, Williams AM, Ford PR. Developmental activities and the acquisition of superior anticipation and decision making in soccer players. J Sports Sci. 2012;30(15):1643–52.

Zibung M, Conzelmann A. The role of specialisation in the promotion of young football talents: a person-oriented study. Eur J Sport Sci. 2013;13(5):452–60.

Hornig M, Aust F, Gullich A. Practice and play in the development of German top-level professional football players. Eur J Sport Sci. 2016;16(1):96–105.

Haugaasen M, Toering T, Jordet G. From childhood to senior professional football: a multi-level approach to elite youth football players’ engagement in football-specific activities. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2014;15(4):336–44.

Côté J, Baker J, Abernethy B. Practice and play in the development of sport expertise. In: Eklund R, Tenenbaum G, editors. Handbook of sport psychology. Hoboken: Wiley; 2007. p. 184–202.

Williams AM, Ward P, Bell-Walker J, et al. Perceptual-cognitive expertise, practice history profiles and recall performance in soccer. Br J Psychol. 2012;103:393–411.

Ford P, Carling C, Garces M, et al. The developmental activities of elite soccer players aged under-16 years from Brazil, England, France, Ghana, Mexico, Portugal and Sweden. J Sports Sci. 2012;30(15):1653–63.

Elbe A, Wikman J. Psychological factors in developing high performance athletes. In: Baker J, Cobley S, Schorer J, Wattie N, editors. Routledge handbook of talent identification and development in sport. London: Routledge; 2017. p. 169–80.

Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1979.

Bronfenbrenner U. Environments in developmental perspective: theoretical and operational models. In: Friedmann L, Wachs T, editors. Measuring environments across life span: emerging methods and concepts. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press; 1999. p. 3–28.

Waldron M, Murphy A. A comparison of physical abilities and match performance characteristics among elite and subelite under-14 soccer players. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2013;25(3):423–34.

Kannekens R, Elferink-Gemser M, Visscher C. Tactical skills of world-class youth soccer teams. J Sports Sci. 2009;27(8):807–12.

Deprez D, Fransen J, Boone J, et al. Characteristics of high-level youth soccer players: variation by playing position. J Sports Sci. 2015;33(3):243–54.

Ostojic SM, Castagna C, Calleja-González J, et al. The biological age of 14-year-old boys and success in adult soccer: do early maturers predominate in the top-level game? Res Sports Med. 2014;22(4):398–407.

Vaeyens R, Malina RM, Janssens M, et al. A multidisciplinary selection model for youth soccer: the Ghent youth soccer project. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(11):928–34.

Gonaus C, Müller E. Using physiological data to predict future career progression in 14- to 17-year-old Austrian soccer academy players. J Sports Sci. 2012;30(15):1673–82.

Mirkov DM, Kukolj M, Ugarkovic D, et al. Development of anthropometric and physical performance profiles of young elite male soccer players: a longitudinal study. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(10):2677–82.

Gil S, Ruiz F, Irazusta A, et al. Selection of young soccer players in terms of anthropometric and physiological factors. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 2007;47(1):25–32.

Gravina L, Gil SM, Ruiz F, et al. Anthropometric and physiological differences between first team and reserve soccer players aged 10–14 years at the beginning and end of the season. J Strength Cond Res. 2008;22(4):1308–14.

Emmonds S, Till K, Jones B, et al. Anthropometric, speed and endurance characteristics of English academy soccer players: do they influence obtaining a professional contract at 18 years of age? Int J Sports Sci Coach. 2016;11(2):212–8.

Malina RM, Ribeiro B, Aroso J, et al. Characteristics of youth soccer players aged 13–15 years classified by skill level. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(5):290–5.

Nevill A, Holder R, Watts A. The changing shape of successful professional footballers. J Sports Sci. 2009;27(5):419–26.

Towlson C, Cobley S, Midgley AW, et al. Relative age, maturation and physical biases on position allocation in elite-youth soccer. Int J Sports Med. 2017;38(3):201–9.

Maria Gil S, Zabala-Lili J, Bidaurrazaga-Letona I, et al. Talent identification and selection process of outfield players and goalkeepers in a professional soccer club. J Sports Sci. 2014;32(20):1931–9.

Coelho e Silva M, Figueiredo A, Simões F, et al. Discrimination of U-14 soccer players by level and position. Int J Sports Med. 2010;31(11):790–6.

Carling C, Le Gall F, Malina R. Body size, skeletal maturity, and functional characteristics of elite academy soccer players on entry between 1992 and 2003. J Sports Sci. 2012;30(15):1683–93.

Deprez D, Coutts AJ, Fransen J, et al. Relative age, biological maturation and anaerobic characteristics in elite youth soccer players. Int J Sports Med. 2013;34(10):897–903.

Hirose N. Relationships among birth-month distribution, skeletal age and anthropometric characteristics in adolescent elite soccer players. J Sports Sci. 2009;27(11):1159–66.

Lovell R, Towlson C, Parkin G, et al. Soccer player characteristics in English lower-league development programmes: the relationships between relative age, maturation, anthropometry and physical fitness. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):1–14.

Meylan C, Cronin J, Oliver J, et al. Talent identification in soccer: the role of maturity status on physical, physiological and technical characteristics. Int J Sports Sci Coach. 2010;5(4):571–92.

Wattie N, Schorer J, Baker J. The relative age effect in sport: a developmental systems model. Sports Med. 2015;45(1):83–94.

Davids K, Button C, Bennet S. Dynamics of skill acquisition: a constraints-led approach. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 2008.

Henriksen K, Stambulova N, Roessler K. Holistic approach to athletic development environments: a successful sailing milieu. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2010;11:212–22.

Mills A, Butt J, Maynard I, et al. Toward an understanding of optimal development environments within elite English soccer academies. Sport Psychol. 2014;28(2):137–50.

Mills A, Butt J, Maynard I, et al. Examining the development environments of elite English football academies: the players’ perspective. Int J Sports Sci Coach. 2014;9(6):1457–72.

Miller PK, Cronin C, Baker G. Nurture, nature and some very dubious social skills: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of talent identification practices in elite English youth soccer. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2015;7(5):642–62.

Ivarsson A, Stenling A, Fallby J, et al. The predictive ability of the talent development environment on youth elite football players’ well-being: a person-centered approach. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2015;16:15–23.

Pazo C, Buñuel P, Fradua L. Influencia del contexto deportivo en la formación de los futbolistas de la selección española de fútbol. Revista de Psicologia del Deporte. 2012;21(2):291–9.

Henriksen K, Stambulova N. Creating optimal environments for talent development. In: Baker J, Cobley S, Schorer J, Wattie N, editors. Routledge handbook of talent identification and development in sport. London: Routledge; 2017. p. 269–84.

Knight C. Family influences on talent development in sport. In: Baker J, Cobley S, Schorer J, Wattie N, editors. Routledge handbook of talent identification and development in sport. London: Routledge; 2017. p. 181–91.

Harter S. The perceived competence scale for children. Child Dev. 1982;53:87–97.

Harter S. The development of competence motivation in the mastery of cognitive and physical skills: a place of joy. In: Roberts G, Landers D, editors. Psychology of motor behavior and sport. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 1981. p. 3–29.

Scanlan TK, Carpenter PJ, Simons JP, et al. An introduction to the sport commitment model. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1993;15(1):1–15.

Ford PR, Low J, McRobert AP, et al. Developmental activities that contribute to high or low performance by elite cricket batters when recognizing type of delivery from bowlers’ advanced postural cues. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2010;32(5):638–54.

Martens R, Vealey R, Burton D. Competitive anxiety in sports. Champaign: Human Kinetics Publishers; 1990.

Rushall BS, Fox RG. An approach-avoidance motivations scale for sports. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1980;5(1):39–43.

Smith RE, Schutz RW, Smoll FL, et al. Development and validation of a multidimensional measure of sport-specific psychological skills: the Athletic Coping Skills Inventory-28. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1995;17(4):379–98.

Wheaton K. A psychological skills inventory for sport. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University; 1998.

Hong E, O’Neil HF. Construct validation of a trait self-regulation model. Int J Psychol. 2001;36(3):186–94.

Howard B, McGee S, Shia R, et al. Metacognitive self-regulation and problem-solving: expanding the theory base through factor analysis. In: Annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association; 24–28 Apr 2000; New Orleans.

Peltier JW, Hay A, Drago W. Reflecting on reflection: scale extension and a comparison of undergraduate business students in the United States and the United Kingdom. J Market Educ. 2006;28(1):5–16.

Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. Generalized self-efficacy scale. In: Weinman S, Johnston M, editors. Measures in health psychology: a user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs. Windsor: NFER-NELSON; 1995. p. 35–7.

VanYperen NW. Interpersonal stress, performance level, and parental support: a longitudinal study among highly skilled young soccer players. Sport Psychol. 1995;9(2):225–41.

Hollenbeck JR, Oleary AM, Klein HJ, et al. Investigation of the construct-validity of a self-report measure of goal commitment. J Appl Psychol. 1989;74(6):951–6.

Folkman S, Lazarus RS. If it changes it must be a process: study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985;48(1):150–70.

Wenhold F, Elbe A-M, Beckmann J. Achievement motives scale–sport (AMS-sport). Fragebogen zum Leistungsmotiv im Sport: Manual [Achievement motives scale–Sport (AMS–Sport). Questionnaire on the achievement motive in sports: manual]. Bonn: Bundesinstitut für Sportwissenschaft; 2009.

Elbe A, Beckmann J. Motivational and selfregulatory factors and sport performance in young elite athletes. In: Hackfort D, Tenenbaum G, editors. Essential processes for attaining peak performance. Aachen: Meyer & Meyer Sport; 2006. p. 137–57.

Demetriou Y. Health promotion in physical education: development and evaluation of the eight week PE programme “HealthyPEP” for sixth grade students in Germany. Hamburg: Forum sportwissenschaft; 2012.

Zago M, Piovan A, Annoni I, et al. Dribbling determinants in sub-elite youth soccer players. J Sports Sci. 2016;34(5):411–9.

Elferink-Gemser MT, Huijgen BC, Coelho-E-Silva M, et al. The changing characteristics of talented soccer players—a decade of work in Groningen. J Sports Sci. 2012;30(15):1581–91.

Hirose N, Seki T. Two-year changes in anthropometric and motor ability values as talent identification indexes in youth soccer players. J Sci Med Sport. 2016;19(2):158–62.

Goto H, Morris JG, Nevill ME. Match analysis of U9 and U10 English premier league academy soccer players using a global positioning system: relevance for talent identification and development. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(4):954–63.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding