Abstract

Objectives

The International Continence Society defines nocturia as the need to void one or more times during the night, with each of the voids preceded and followed by sleep. The chronic sleep disturbance and sleep deprivation experienced by patients with nocturia affects quality of life, compromising both mental and physical well-being. This paper aims to characterise the burden of nocturia by comparing published data from patients with nocturia with data from patients with any of 12 other common chronic conditions, specifically focusing on its impact on work productivity and activity impairment, as measured by the instrument of the same name (WPAI).

Methods

A systematic literature review of multiple data sources identified evaluable studies for inclusion in the analysis. Study eligibility criteria included use of the WPAI instrument in patients with one of a predefined list of chronic conditions. We assessed the quality of each included study using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale and extracted basic study information, work and activity impairment data. To assess how work and activity impairment from nocturia compares with impairment from other common chronic diseases, we conducted two data syntheses (pooled and unpooled).

Results

The number of evaluable studies and the range of overall work productivity impairment reported, respectively, were as follows: nocturia (3; 14–39 %), overactive bladder (5; 11–41 %), irritable bowel syndrome/constipation (14; 21–51 %), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (13; 6–42 %), asthma/allergies (11; 6–40 %), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (7; 19–42 %), sleep problems (3; 12–37 %), arthritis (13; 21–69 %), pain (9; 29–64 %), depression (4; 15–43 %) and gout (2; 20–37 %).

Conclusions

The overall work productivity impairment as a result of nocturia is substantial and was found to be similar to impairment observed as a result of several other more frequently researched common chronic diseases. Greater awareness of the burden of nocturia, a highly bothersome and prevalent condition, will help policy makers and healthcare decision makers provide appropriate management of nocturia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This paper characterises the available evidence on the burden of nocturia and provides context by comparing data from patients with nocturia with data from patients with any of 12 other common chronic conditions, specifically focusing on the effects of nocturia on work productivity and activity impairment. |

Overall work productivity impairment as a result of nocturia is substantial and similar to impairment observed as a result of several other more frequently researched common chronic diseases that physicians may more actively manage. |

Greater awareness of the burden of nocturia, a highly bothersome and prevalent condition, will help policy makers and healthcare decision makers provide appropriate management of nocturia. |

1 Introduction

The International Continence Society defines nocturia as the need to routinely void one or more times during the night, with each of the voids preceded and followed by sleep [1], with two or more voids per night established as an average threshold of bothersomeness [2]. The chronic sleep disturbance and sleep deprivation experienced by patients with nocturia affects their entire health-related quality of life (HRQoL), compromising both mental and physical well-being. While it is well established that the prevalence of nocturia increases with age [3], prevalence among those aged 40–65 years is reported to be as high as 50 % [4]. The burden of many chronic diseases on HRQoL is well documented, including—often where multiple age groups are affected—the impact on work productivity and activity impairment. This impact of nocturia and, indeed, how it may compare with the impact of other chronic diseases is less well documented.

1.1 Description of the Condition

Lower urinary tract symptoms are often taboo, and patients are therefore hesitant to seek help [5]. Nocturia was not defined as a standalone symptom before 1999 [6], but it is still often only understood as a symptom of overactive bladder (OAB) and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Discussion is ongoing as to whether a diagnosis of BPH and especially OAB is too broad and symptom based and leads to misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment [7].

The medical definition of nocturia is abnormally excessive urination during the night. Nocturia may be a symptom of systemic disease. Nocturia without polyuria (the passage of large volumes of urine with an increase in urinary frequency) can be a consequence of (1) loss of normal diurnal variation in solute excretion because of oedema-forming states: congestive heart failure, cirrhosis and nephrotic syndrome; chronic renal disease; advanced age and side effects from drugs (β-adrenergic blockage, diuretics); and (2) loss of renal-concentrating ability because of chronic renal disease or malnutrition. Nocturia with polyuria (about 75 % of the nocturia cases [8]) can be a consequence of (1) water diuresis associated with pituitary or nephrogenic diabetes insipidus or psychogenic water drinking, (2) solute diuresis because of endogenous or exogenous factors and (3) combined water and solute diuresis. Pathophysiologically, nocturia is largely attributed to nocturnal polyuria (nocturnal urine overproduction generally defined as >33 % or 24-h urine volume), which is often due to an altered endogenous production of arginine vasopressor hormone.

This paper highlights what is known about the burden that nocturia places on patients in terms of its impact on work productivity and activity impairment relative to other generally more well-researched common chronic diseases. This greater awareness of the burden of nocturia, a highly bothersome and prevalent condition, will help policy makers and healthcare decision makers to provide appropriate management of nocturia.

1.2 Objectives

Our objective was to characterise the burden of nocturia by comparing data from patients with nocturia with data from patients with any of 12 other common chronic conditions, specifically focusing on the effect on work productivity and activity impairment, as measured by the instrument of the same name (WPAI) [9].

2 Methods

2.1 Types of Studies

In the literature searches, we placed no restriction on study design, including both observational and interventional studies and recording study design. For interventional studies, we used only baseline WPAI data in this review. Extracted data from studies with concurrent control groups, matched case–control studies, are presented by study arm. We also included data from cohort studies in the review.

We conducted systematic electronic searches of MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase, EconLit, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (DSR), the American College of Physicians (ACP) Journal Club, and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), with no restrictions on publication date or language. We used a pragmatic selection of a wide range of chronic diseases affecting physical and mental health as well as multiple aspects of HRQoL, did not apply any filters to restrict searches to specific study designs and used the following specific search terms: WPAI nocturia, WPAI OAB, WPAI IBS, WPAI constipation, WPAI GERD, WPAI asthma, WPAI rhinitis/allergy, WPAI COPD, WPAI sleep, WPAI arthritis, WPAI pain, WPAI depression and WPAI gout. We also conducted a systematic search of the WPAI registry of studies [15], a voluntary registry to which authors can submit publications of studies involving the WPAI instrument.

2.2 Types of Outcome Measures

Work productivity is increasingly recognised as a valuable way to capture the multifaceted impact of chronic health issues on patients’ lives. The frequently used validated measures include the WPAI [9], the Health and Labour Questionnaire (HLQ) [10], the Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ) [11], the Work Ability Index (WAI) [12] and the Health and Work Productivity Questionnaire (HPQ) [13]. To date, the impact and burden of nocturia has been under researched; the modified WLQ [11] has been used in studies of OAB with nocturia [14], but only the WPAI [9] instrument has been used in studies specific to patients with nocturia. The WPAI measure has been extensively used to study many other health issues. Since comparison across different measures is problematic, we selected work productivity and activity impairment specifically measured by the WPAI [9] instrument as the primary outcome measure for this study.

The WPAI instrument produces four outcome measures: (1) the percentage work time missed due to the specific health problem; (2) the percentage impairment while working due to the specific health problem; (3) the percentage overall work impairment (1 + 2) due to the specific health problem; and (4) the percentage activity impairmentFootnote 1 due to the specific health problem. Studies reporting at least one of these outcome measures were eligible for inclusion in this review.

The WPAI instrument is free to use and not licensed. The authors’ instructions for use state that the questionnaire cannot be called the WPAI if questions or responses are changed or questions are added or deleted. Three primary versions of the WPAI instrument exist, with only slight variations in the wording used. In the general health version (WPAI: GH), respondents are asked questions about work and activity impairment due to health problems. In the specific health problem version (WPAI: SHP), respondents are asked questions concerning impairment due to the target health problem (e.g. arthritis). In the combination version, WPAI: GH/SHP respondents are asked about impairment due to a specified health problem and impairment due to other health reasons. The WPAI can be adapted to a specific disease or health problem; if no other changes are made, the resulting instrument can be referred to as the WPAI. Users are cautioned that although the discriminative validity and reproducibility of the SHP version has been established, evidence for evaluative validity and responsiveness to clinically meaningful change has only been established for some diseases [15]. For peer-reviewed studies included in this review, we assumed the WPAI instrument was used in accordance with its authors’ instructions.

2.3 Types of Participants

For this study, we were primarily interested in participants with nocturia. Once we had selected the WPAI instrument as the primary outcome measure, we reviewed the full WPAI database of studies [15]Footnote 2 and made a pragmatic selection of a list of chronic diseases for which multiple WPAI studies had been completed, applying no other criteria to the selection of comparison studies. Of course, further comparison with other WPAI studies is feasible.

Patients with any of the following 12 common chronic conditionsFootnote 3 were included in the review: OAB, COPD, IBS, constipation, sleep problems (with multiple factors), asthma, arthritis, depression, pain (from multiple causes), rhinitis/allergies, GERD or gout.

Participants in studies reporting work productivity and activity impairment are predominantly but not exclusively in paid employment. We placed no restriction on the nature of a participant’s employment for this review. The WPAI instrument instructions for use require that only data on activity impairment are collected for participants who are not employed.

2.4 Data Collection and Analysis

2.4.1 Selection of Studies

Two researchers (PM, HH) independently applied the inclusion/exclusion criteria to the selection of studies and, after reconciliation, reached agreement. Figure 1 is a preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram [16] showing the study selection process. After we removed duplicate publications, we screened records and excluded any that were found to be multiple publications of the same WPAI study data, contained insufficient WPAI data for the objective of this review, or studied disease areas outside the scope of this review (acute or less common conditions).

2.4.2 Data Extraction and Management

The researchers completed a data abstraction form summarising the study design, study population, method of exposure assessment, and analysis methods for each included study. This form was informed by the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) statement [17]. Data on participants’ primary health condition, subgroup (if any), age, sex and country of residence were extracted for tabulation. For case–control studies, all data were also extracted and presented for control groups as well as statistical analyses comparing groups.

We assessed the quality of all included studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale [18], which is included in the Cochrane handbook [19] of methods for reviewing non-randomised studies. The Newcastle–Ottawa scale assesses a study on three broad perspectives: selection of study groups, comparability of study groups, and ascertainment of either the exposure or the outcome of interest for case–control or cohort studies, respectively. A study can be awarded a maximum of one star for each of four numbered items within the selection category and three numbered items in the exposure/outcome categories. A study can obtain a maximum of two stars for the comparability category.

2.4.3 Data Synthesis

It was difficult to conduct a meta-analysis of WPAI data from these studies because data at the study level was insufficient for us to make any informed judgements to control for relevant patient-, disease- or job-related covariates; patient-level data were unavailable. We conducted two data syntheses to assess how work and activity impairment as a result of nocturia compares with impairment as a result of other common chronic diseases. First, we collated (but did not pool) all evaluable WPAI data by disease area to show the range of estimated work and activity impairment within and across disease areas. Second, we pooled and weighted all evaluable work and activity impairment data by study size to provide a central estimate for each disease area. We plotted disease area work and activity impairment estimates within the observed range for each disease area to show how they compared within and across disease areas.

In addition, to highlight how the different nocturia subgroups compared with other disease areas, we organised the full dataset of all evaluable work and activity impairment data, including all reported subgroups, in descending order of impairment. Comparative rank order for nocturia studies is reported for both overall work impairment and overall activity impairment.

3 Results

3.1 Included Studies

We included 84 studies in the review: three nocturia studies [20–22], five OAB studies [23–27], 14 IBS/constipation studies [28–41], 13 GERD studies [42–54], 11 asthma/allergies studies [55–65], seven COPD studies [66–72], three sleep studies [73–75], 13 arthritis studies [76–88], nine pain studies [89–97], four depression studies [98–101] and two gout studies [102, 103].

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of studies collated by disease area. As expected, the number of studies and evaluable patients was lower for nocturia than for other disease areas. The overall evaluable sample for nocturia was very similar in age to the sample for OAB, COPD and gout, whereas studies of other disease areas involved younger patients. Studies of nocturia, COPD and gout predominantly involved male patients, whereas others involved predominantly females. The evaluable samples for nocturia and OAB included international studies, whereas other disease areas were more likely to be from single countries.

The included studies are presented in Table 2 (cohort studies) and Table 3 (case–control studies). The total evaluable dataset for this review, including all subgroups and controls reporting at least one WPAI outcome measure, consisted of 113 groups (all rows of Tables 2 and 3). Although most studies used the WPAI: SHP version of the instrument, 16 used WPAI: GHFootnote 4 (essentially those that assessed multiple diseases within the same study).

Tables 2 and 3 show the quality assessment of each included study according to the three Newcastle–Ottawa scale categories [18]. Overall, cohort studies scored relatively poorly, scoring either one or two stars (out of a possible four) on the selection criteria due to representativeness of the exposed cohort or ascertainment of the exposure; few studies scored stars on the comparability criteria, where study design or analysis must show how confounding factors are controlled; and no studies scored stars on the outcome criteria—essentially because WPAI is a self-report measure, data were cross-sectional and studies did not report the handling of non-response/missing data in sufficient detail. As expected, case–control studies generally scored more highly on the quality-assessment scale, included studies scored well on the selection criteria (three or four stars out of four); all studies scored a maximum of two stars on the comparability criteria; most studies scored one star (out of three) on the exposure criteria.

3.2 Excluded Studies

We excluded 427 of the publications that were initially identified during the searches: 295 did not present WPAI data; 59 had insufficient WPAI data—most of these were validation studies testing psychometric properties of the instruments in various diseases; 68 were identified as multiple publications of another WPAI dataset; 25 presented data on diseases outside the scope of this review (e.g. breast cancer); ten were published in languages other than English.

3.3 Effects on Work Productivity and Activity Impairment

The 645 patients with nocturia who were recruited to two clinical trials (N4) [21] had a mean baseline overall work impairment of 24 %, and greater disease severity was associated with greater work impairment: the subgroup with four night-time voids (N4c) [21] had mean work impairment of 30 %, the subgroup with five or more voids (N4d) [21] had mean work impairment of 39 %. For 2244 patients with nocturia recruited via their physician to an international cross-sectional real-world survey (N5) [22], mean overall work impairment was reported as 29 %, and greater disease severity was associated with greater work impairment: the subgroup of females with both nocturia and OAB (N5c) [22] had a mean work impairment of 32.5 %, and the subgroup with four or more night-time voids had a mean work impairment of 35 %. In addition to effects on work productivity impairment, this observational study also reported that a deterioration in a range of outcome measures (utility, HRQoL, disease impact diary) was associated with an increasing number of night-time voids (p < 0.0001). For 203 respondents self-reporting less severe nocturia symptoms (mean of 1.8 voids in the previous night) in a Swedish population-based study (N1) [20], mean overall work impairment was reported as 14 % and significantly higher than for a matched control group. A regression analysis estimated an average of an additional 2 % work impairment for each additional night-time void.

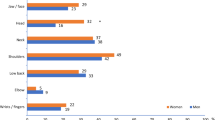

Figure 2a shows the ranges of percentage overall work productivity impairment due to each health problem identified in this review, as follows: nocturia (14–39 %), OAB (11–41 %), IBS/constipation (21–51 %), GERD (6–42 %), asthma/allergies (6–40 %), COPD (19–42 %), sleep problems (12–37 %), arthritis (21–69 %), pain (29–64 %), depression (15–43 %) and gout (20–37 %). Work productivity impairment reported by patients with nocturia is broadly in line with that in many other chronic diseases such as GERD, asthma/allergies, sleep problems, OAB and gout, whereas WPAI data for arthritis and pain show higher levels of impairment. Similar results were found for the other three outcome measures included in the WPAI instrument.

Range of percentage overall work impairment due to health problem found in multiple studies for chronic disease conditions using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment instrument. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, GERD gastroesophageal reflux disease, IBS irritable bowel syndrome OAB overactive bladder

The ranges of percentage overall work time missed due to each health problem were as follows: nocturia (2–9 %), OAB (1–6 %), IBS/constipation (2–13 %), GERD (1–9 %), asthma/allergies (2–10 %), COPD (5–7 %), sleep problems (3–12 %), arthritis (5–14 %), pain (5–40 %), depression (5–8 %) and gout (7–23 %).

The ranges of percentage impairment while working due to each health problem were as follows: nocturia (12–32 %), OAB (9–44 %), IBS/constipation (20–40 %), GERD (6–40 %), asthma/allergies (10–35 %), COPD (10–31 %), sleep problems (11–43 %), arthritis (18–49 %), pain (25–87 %), depression (19–35 %) and gout (14–33 %).

The ranges of percentage activity impairment due to each health problem were as follows: nocturia (18–40 %), OAB (29–47 %), IBS/constipation (32–57 %), GERD (8–45 %), asthma/allergies (6–50 %), COPD (13–65 %), sleep problems (18–62 %), arthritis (23–59 %), pain (38–71 %), depression (27 %) and gout (29–54 %).

Figure 2b shows disease area WPAI estimates, where study level mean WPAI data are pooled and weighted by study size only, plotted within the observed range for each disease area to show how these compare within and across disease areas. This analysis shows that work impairment among patients with nocturia is estimated to be somewhat central within the range of disease areas included in this review: higher than five disease areas (GERD, asthma/allergies, sleep problems, OAB and gout) and lower than five disease areas (depression, IBS/constipation, COPD, arthritis and pain conditions).

When organising WPAI results for all 113 groups included in this review by descending rank order of mean percentage overall work and activity impairment, nocturia studies (all severities) rank around the middle of this full dataset (Figs. 3, 4). The most severe subgroups (highest number of voids per night) from nocturia studies N4d [21] and N5c [22] rank 15th and 35th, respectively, of 113.

4 Discussion

4.1 Summary of Main Results

Work and activity impairment has been studied for longer, in more studies and among more patients within the 12 common chronic conditions used as comparators than in studies on nocturia. Analysis of the ranges of reported impairment due to these conditions, pooled estimates for each disease area, and ranking analyses all find that patients with nocturia report neither the highest nor the lowest work and activity impairment within this dataset. Overall work impairment for nocturia identified in this review ranges from 14 to 39 %. The pooled estimate for the three nocturia studies included is 27 % work impairment. Nocturia studies rank very centrally within this dataset: nocturia study N5 [22] ranks 43rd of 113 studies ordered by work impairment, and nocturia study N4 [21] ranks 60th of 113.

Comparing the ranges of overall work impairment results across chronic diseases shows that the upper estimates of the range identified for each study in this review is very similar for a number of disease conditions. The results of studies in patients with seven of the disease conditions included in this review (OAB, GERD, asthma/allergies, COPD, sleep problems, depression, gout) are very similar to those in patients with nocturia, with all reporting an upper estimate of mean percentage overall work impairment around 40 %. Lower estimates of the range of overall work impairment reported for these diseases are also very similar, except for asthma/allergies (6–40 %), which includes patients with much lower impairment, and IBS/constipation (21–51 %) and gout (20–37 %), which have higher lower ranges. Studies of patients with arthritis and pain conditions report higher ranges of overall work impairment than those with other chronic disease conditions in this review: 21–69 % and 29–64 %, respectively.

The WPAI measure of overall work impairment is an aggregation of work time missed (absenteeism) and impairment while working (presenteeism), hence similar patterns of impairment across the diseases included in this review are also found for the WPAI metrics of absenteeism and presenteeism.

All three nocturia studies identified in this review measured activity impairment, which can also be reported among non-working participants. Three nocturia studies found a range of mean percentage activity impairment: 33–40 % [21], 37–40 % [22] and 18 % [20]. The ranges identified for mean percentage activity impairment for each health problem are considerably wider than for other WPAI outcome measures. For example, activity impairment among studies of asthma/allergies ranged from 6 to 50 %. This increased variability may be due to the inclusion in some studies of retired (non-working) participants who may be older and have more severe disease and co-morbidities.

4.2 Overall Completeness and Applicability of Evidence

This review aimed to characterise the burden of nocturia by considering published data from studies of patients with nocturia and patients with any of 12 other common chronic conditions. The consolidated descriptive presentation of the available evidence in this area provides context for this comparison. We identified 84 studies, with an aggregate of more than 128,000 patients with the target disease areas having completed the WPAI instrument and 113 patient groups containing at least one of the WPAI outcome measures. This constitutes a reasonable body of evidence with which to meet the research objectives.

Meta-analyses of WPAI data from these studies were problematic, since study-level data from the publications were insufficient to enable informed judgements to control for relevant patient-, disease- and job-related covariates; no patient-level data were available. Pooled estimates of mean work impairment were estimated for each disease area, adjusting only for the size of studies contributing to each pool. Comparison of baseline characteristics at the study level was restricted to age, percentage male/female and study setting (single country vs. international study); meta-analyses adjusting for these and other potentially relevant parameters would require more information than could be obtained from the review of published literature.

We based our selection of chronic disease conditions to compare with nocturia and include in the review on clinical judgement of appropriateness and data manageability; clearly, other diseases could be added to the review where suitable. It may be appropriate to consider comparing the extent of impairment in other areas in which WPAI studies have been conducted, including hypertension, women’s health, dermatology, diabetes, eye diseases and mental health disorders.

This review of work productivity and activity impairment was restricted to studies focused on one instrument: the WPAI. We selected this based on the authors’ experience that the WPAI is the most widely used across a large range of disease areas and has been subject to rigorous validation in many contexts in many countries. The review could, of course, be extended to include other measures of work productivity and activity impairment, but it may not be possible to combine the results of different measures and they may need to be presented independently. A wider review of other measures of the burden of chronic diseases, such as disease-specific and generic HRQoL measures could also be conducted. This review did extract HRQoL data from the identified studies to facilitate further analyses in this area.

The use of work productivity instruments, such as the WPAI, within both intervention and observational studies appears to be increasing, perhaps as healthcare decision makers and policy makers are attaching more weight to these types of measures of disease burden. Generally, productivity measures remain as supportive evidence in most health technology assessments of new medicines and technologies, although a few systems now formally incorporate them.

Further productivity data among a wider range of patients with nocturia will further characterise the burden of this condition and increase comparability with other diseases. Further burden-of-illness type studies are needed to contribute to this evidence base, but studies should consider the quality assessment of studies included in this review and which study design aspects may be enhanced to deliver better quality scores on the Newcastle–Ottawa scale [18] or similar. Well-conducted case–control studies that better document non-responder characteristics and the handling of missing data would be valuable.

4.3 Potential Biases in the Review Process

Two main potential biases might affect the findings of this review. First, confounding factors, such as age, disease severity and co-morbidities, may be unevenly distributed across studies, countries and disease groupings. Second, participants in WPAI studies may be systematically different to non-participants with the chronic health problems, leaving the review at risk of selection bias. Studies collecting WPAI data as part of a randomised controlled trial tended to report greater work and activity impairment, although differences were not formally tested.

5 Conclusion

Although the data published for nocturia are still limited and meta-analyses are somewhat constrained by the study-level information available from published sources, the overall work productivity impairment as a result of nocturia would appear to be substantial and similar to that of several other more frequently researched common chronic diseases. Greater awareness of the burden of nocturia, a highly bothersome and prevalent condition, will help policy makers and healthcare decision makers provide appropriate management of nocturia.

Notes

WPAI instructions for activity impairment: “By regular activities, we mean the usual activities you do, such as work around the house, shopping, childcare, exercising, studying, etc. Think about times you were limited in the amount or kind of activities you could do and times you accomplished less than you would like. If health problems affected your activities only a little, choose a low number. Choose a high number if health problems affected your activities a great deal.”

The WPAI database of studies (http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_References.html) includes the following health issues: anemia, angioedema, ankylosing spondylitis, arthritis, asthma/allergies, cancer, caregivers, Crohn's disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), dermatology, diabetes, dyspepsia, erectile dysfunction, eye disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), general health, gout, headache, hepatitis, HIV/AIDS, hypertension, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)/chronic constipation, lupus, mental health, multiple sclerosis, neurology, nocturia, obesity/nutrition, OAB, pain, peripheral artery disease (PAD), respiratory, restless legs syndrome, rhinosinusitis, sleep, spondyloarthritis, substance abuse, ulcerative colitis, urinary incontinence, voice disorders, women's health.

For analysis, constipation is combined with IBS, and asthma is combined with rhinitis/allergies, hence 12 common chronic conditions are organised into ten categories to compare with nocturia.

References

van Kerrebroeck P, Abrams P, Chaikin D, Donovan J, Fonda D, Jackson S, Jennum P, Johnson T, Lose G, Mattiasson A, Robertson G, Weiss J. Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. The standardisation of terminology in nocturia: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:179–83.

Tikkinen KA, Johnson TM 2nd, Tammela TL, Sintonen H, Haukka J, Huhtala H, Auvinen A. Nocturia frequency, bother, and quality of life: how often is too often? A population-based study in Finland. Eur Urol. 2010;57:488–96.

Bosch JL, Weiss JP. The prevalence and causes of nocturia. J Urol. 2010;184:440–6.

Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S, Reilly K, Kopp Z, Herschorn S, Coyne K, Kelleher C, Hampel C, Artibani W, Abrams P. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol. 2006;50:1306–14.

Strickland R. Reasons for not seeking care for urinary incontinence in older community-dwelling women: a contemporary review. Urol Nurs. 2014;34(2):63–8, 94.

Van Kerrebroeck P, Weiss J. Standardization and terminology of nocturia. BJU Int. 1999;84(Suppl 1):1–4.

Drake MJ. Do we need a new definition of the overactive bladder syndrome? ICI-RS 2013. Neurourol Urodyn. 2014;33(5):622–4.

Van Kerrebroeck P, Hashim H, Holm-Larsen T, Robinson D, Stanley N. Thinking beyond the bladder: antidiuretic treatment of nocturia. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(6):807–16.

Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–65.

Van Roijen L, Essink-Bot ML, Koopmanschap MA, et al. Labour and health status in economic evaluations of health care. Int J Tech Assess Health Care. 1996;12:405–15.

Lerner D, Amick BC III, Rogers WH, et al. The work limitations questionnaire. Med Care. 2001;39:72–85.

Tuomi K, Ilmarinen J, Jahkola A, Katajarinne L, Tulkki A. Work Ability Index. 2nd revised edition. Helsinki: Finnish Institute of Occupational Health; 1998.

Kessler R, Barber C, Beck A. The World Health Organization health and work performance questionnaire (HPQ). J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45:156–74.

Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Kopp ZS, Ebel-Bitoun C, Milsom I, Chapple C. The impact of overactive bladder on mental health, work productivity and health-related quality of life in the UK and Sweden: results from EpiLUTS. BJU Int. 2011;108(9):1459–71.

Reilly Associates. Health outcomes research. http://www.reillyassociates.net/Index.html. Accessed Jun 2016.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–41.

Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, Poole C, Schlesselman JJ, Egger M; STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1500–24.

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute 2011. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed June 2016.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

Kobelt G, Borgstrom F, Mattiasson A. Productivity, vitality and utility in a group of healthy professionally active individuals with nocturia. Br J Urol Int. 2003;9(3):190–5.

Andersson F, Blemings A, Holm Larsen T, Nørgaard JP. Waking at night to void can have a profound impact on productivity. Value Health. 2013;16(3):A184.

Biliotti B, Andersson F, Anderson P, Piercy J. Nocturia results in work productivity and activity losses comparable with other chronic diseases. Neurourol Urodyn. 2014;33:779.

Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Irwin DE, Kopp ZS, Kelleher CJ, Milsom I. The impact of overactive bladder, incontinence and other lower urinary tract symptoms on quality of life, work productivity, sexuality and emotional well-being in men and women: results from the EPIC study. BJU Int. 2008;101(11):1388–95.

Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Thompson CL, Clemens JQ, Chen CI, Bavendam T, Dmochowski R. Impact of overactive bladder on work productivity. Urology. 2012;80(1):97–103.

Lee HE, Cho SY, Lee S, Kim M, Oh SJ. Short-term effects of a systematized bladder training program for idiopathic overactive bladder: a prospective study. Int Neurourol J. 2013;17(1):11–7.

Péntek M, Gulácsi L, Majoros A, Piróth C, Rubliczky L, Böszörményi Nagy G, Törzsök F, Timár P, Baji P, Brodszky V. Health related quality of life and productivity of women with overactive bladder. Orv Hetil. 2012;153(27):1068–76.

Tang DH, Colayco DC, Khalaf KM, Piercy J, Patel V, Globe D, Ginsberg D. Impact of urinary incontinence on healthcare resource utilization, health-related quality of life and productivity in patients with overactive bladder. BJU Int. 2014;113(3):484–91.

Bracco A, Reilly MC, McBurney C, Ambegaonkar B. Burden of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation on health care resource utilization, work productivity and activity impairment and quality of life. 13th World Congress of Gastroenterology; Montreal; September 10–14, 2005. Available from (http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_References.html).

Bracco A, Reilly MC, McBurney C, Ambegaonkar B. Burden of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation on health care resource utilisation, work productivity and activity impairment and quality of life in France, Germany and United Kingdom. United European Gastroenterology Week; Copenhagen; Oct 15–19, 2005. Available from: http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_References.html.

Buono JL, Tourkodimitris S, Sarocco P, Johnston JM, Carson RT. Impact of linaclotide treatment on work productivity and activity impairment in adults with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: results from 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2014;7(5):289–97.

Dean BB, Aguilar D, Barghout V, Kahler KH, Frech F, Groves D, Ofman JJ. Impairment in work productivity and health-related quality of life in patients with IBS. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:S17–26.

Dibonaventura MD, Prior M, Prieto P, Fortea J. Burden of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C) in France, Italy, and the United Kingdom. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2012;5:203–12.

Dibonaventura M, Sun SX, Bolge SC, Wagner JS, Mody R. Health-related quality of life, work productivity and health care resource use associated with constipation predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(11):2213–22.

Neri L, Basilisco G, Corazziari E, Stanghellini V, Bassotti G, Bellini M, Perelli I, Cuomo R, LIRS Study Group. Constipation severity is associated with productivity losses and healthcare utilization in patients with chronic constipation. United European. Gastroenterol J. 2014;2(2):138–47.

Pare P, Lam S, Balshaw R, et al. Patient characteristics (irritable bowel syndrome with constipation [IBS-C]): baseline results from LOGIC (Longitudinal Outcomes study of GI symptoms in Canada). Presented American College of Gastroenterology October 30, 2005, Honolulu, Hawaii. Available from: http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_References.html.

Reilly MC, Barghout V, McBurney CR, Niecko TE. Effect of tegaserod on work and daily activity in IBS with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:373–80.

Reilly MC, Bracco A, Geissler K, Johanson J, Kahler KH. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) on work productivity and daily activities. 69th Annual Meeting American College of Gastroenterology; Orlando FL; 3 Nov 2004. Available from: http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_References.html.

Sun SX, Dibonaventura M, Purayidathil FW, Wagner JS, Dabbous O, Mody R. Impact of chronic constipation on health-related quality of life, work productivity, and healthcare resource use: an analysis of the National Health and Wellness Survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(9):2688–95.

Engsbro AL, Begtrup LM, Kjeldsen J, Larsen PV, de Muckadell OS, Jarbøl DE, Bytzer P. Patients suspected of irritable bowel syndrome: cross-sectional study exploring the sensitivity of Rome III Criteria in primary care. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(6):972–80.

Stanghellini V, Lecchi A, Mackinnon J, Bertsch J, Fortea J, Tack J. 2015 Economic and quality-of-life burden of moderate-to-severe irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) in Italy: The IBIS-C study. Digestive and Liver Disease Conference 21st National Congress of Digestive Diseases, Italian Federation of Societies of Digestive Diseases, FISMAD 2015; Bologna, Italy; 25–28 March 2015: e129.

Yiannakou Y, Eugenicos M, Sanders DS, Emmanuel A, Whorwell P, Butt F, Bridger S, Arebi N, Millar A, Kaushik V, Rance M, Mackinnon J, Bertsch J, Fortea J, Tack J. 2015 Economic and quality-of-life burden of moderate-to-severe irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) in the UK: The IBIS-C study. Gut Conference 2nd Digestive Disorders Federation Conference, DDF; July 22–25, 2015; London, p. A33–4.

Bixquert M, Calleja J, Maldonado J, Ballesteros E, Vara S, Rico-Villademoros F. Impact of nocturnal heartburn on quality of life, sleep and productivity: the Sinerge Study. Gut 2004; 53(Suppl V1):A99.

Bruley des Varannes S, Ducrotté P, Vallot T, Garofano A, Bardoulat I, Carrois F, Ricci L. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: Impact on work productivity and daily-life activities of daytime workers. A French cross-sectional study. Dig Liver Dis. 2013; 45(3):200–6.

Dean BB, Crawley JA, Schmitt CM., Ofman JJ. The Impact of GERD Symptoms on Worker Productivity and Absenteeism. ACG Meeting 2001. Available from: http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_References.html.

El-Dika S, Guyatt GH, Armstrong D, Degl’innocenti A, Wiklund I, et al. The impact of illness in patients with moderate to severe gastro-esophageal reflux disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2005;5:23.

Gisbert JP, Cooper A, Karagiannis D, Hatlebakk J, Agréus L, Jablonowski H, Nuevo J. Impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on work absenteeism, presenteeism and productivity in daily life: a European observational study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:90.

Gross M, Beckenbauer U, Burkowitz J, Walther H, Brueggenjuergen B. Impact of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease on work productivity despite therapy with proton pump inhibitors in Germany. Eur J Med Res. 2010;15(3):124–30.

Mody R, Bolge SC, Kannan H, Fass R. Effects of gastro-esophageal reflux disease on sleep and outcomes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(9):953–9.

Nordyke RJ, Aguilar D, Lee A, Singh A, Tedeschi MR, Dubois RW. Linking symptoms diurnality to productivity loss- a new conceptual approach. Presented ISPOR Tenth Annual International Meeting, May 17, 2005, Washington, DC. Available from http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_References.html.

Shin WG, Kim HU, Kim SG, Kim GH, Shim KN, Kim JW, Kim JI, Kim JG, Kim JJ, Yim DH, Park SK, Park SH. The Korean College of Helicobacter and Upper Gastrointestinal Research. Work productivity and activity impairment in gastroesophageal reflux disease in Korean full-time employees: a multicentre study. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(4):286–91.

Wahlqvist P, Bergenheim K, Långström G, Næsdal J. Impact on work productivity of upper gastrointestinal symptoms associated with chronic NSAID therapy in a Swedish study population. Value Health. 2003;6(6):A688.

Wahlqvist P, Carlsson J, Stalhammar NO, Wiklund I. Validity of a work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire for patients with symptoms of gastro-esophageal reflux disease (WPAI-GERD) results from a cross-sectional study. Value Health. 2002;5:106–13.

Wahlqvist P, Reilly M, Barkun A. Systematic review: the impact of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease on work productivity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24(2):259–72.

Rokkas T, Panitti E, Nikas N. Prevalence and impact in work productivity of gastroesofageal reflux disease (GERD) in primary care patients with upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. The Greek GERDQ study. ISPOR 13th Annual European Congress Prague Czech Republic. Conference Publication: 2010;13(7):A373.

Andréasson E, Svensson K, Berggren F. The validity of the work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire for patients with asthma (WPAI-asthma): Results from a web-based study. ISPOR 6th Annual European Congress; 9–11 November 2003; Barcelona, Spain. Available from: http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_References.html.

Bousquet J, Neukirch F, Bousquet PJ, Gehano P, Klossek JM, Le Gal M, Allaf B. Severity and impairment of allergic rhinitis in patients consulting in primary care. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(1):158–62.

Calhoun WJ, Haselkorn T, Mink DR, Miller DP, Dorenbaum A, Zeiger RS. Clinical burden and predictors of asthma exacerbations in patients on guideline-based steps 4–6 asthma therapy in the TENOR cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(2):193–200.

Chen H, Blanc PD, Chawla A, Hayden M, Bleeker ER, Lee JH. Assessing productivity impairment in patients with severe or difficult to treat asthma: validation of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment- Asthma questionnaire. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2):S181.

de la Hoz Caballer B, Rodríguez M, Fraj J, Cerecedo I, Antolín-Amérigo D, Colás C. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on work productivity in primary care practice and a comparison with other common diseases: The cross-sectional study to evaluate work productivity in allergic rhinitis compared with other common diseases (CAPRI) study. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26(5):390–4.

Dean BB, Calimlim BC, Sacco P, Aguilar D, Maykut R, Tinkelman D. Uncontrolled asthma: assessing quality of life and productivity of children and their caregivers using a cross-sectional Internet-based survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8(8):96.

Demoly P, Annunziata K, Gubba E, Adamek L. Repeated cross-sectional survey of patient-reported asthma control in Europe in the past 5 years. Eur Respir Rev. 2012;21(123):66–74.

Eisner MD, Yegin A, Trzaskoma B. Severity of asthma score predicts clinical outcomes in patients with moderate to severe persistent asthma. Chest. 2012;141(1):58–65.

Reilly MC, Tanner A, Meltzer EO. Allergy impairment questionnaires: validation studies. J Allergy Clin Immunology 1996; 97:1:3:430.

Stankiewicz J, Tami T, Truitt T, Atkins J, Winegar B, Cink P, Schaeffer BT, Raviv J, Henderson D, Duncavage J, Hagaman D. Impact of chronic rhinosinusitis on work productivity through one-year follow-up after balloon dilation of the ethmoid infundibulum. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011;1(1):38–45.

Tan H, Sarawate C, Singer J, Elward K, Cohen RI, Smart BA, Busk MF, Lustig J, O’Brien JD, Schatz M. Impact of asthma controller medications on clinical, economic, and patient-reported outcomes. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(8):675–84.

Allen-Ramey FC, Gupta S, Dibonaventura MD. Patient characteristics, treatment patterns, and health outcomes among COPD phenotypes. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:779–87.

Dacosta Dibonaventura M, Paulose-Ram R, Su J, McDonald M, Zou KH, Wagner JS, Shah H. The impact of COPD on quality of life, productivity loss, and resource use among the elderly United States workforce. COPD. 2012;9(1):46–57.

Dibonaventura MD, Paulose-Ram R, Su J, McDonald M, Zou KH, Wagner JS, Shah H. The burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among employed adults. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:211–9.

Fletcher MJ, Upton J, Taylor-Fishwick J, Buist SA, Jenkins C, Hutton J, Barnes N, Van Der Molen T, Walsh JW, Jones P, Walker S. COPD Uncovered: an International survey on the impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) on a working age population. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):612.

Galaznik A, Chapnick J, Vietri J, Tripathi S, Zou KH, Makinson G. Burden of smoking on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;13(6):853–60.

Solem CT, Sun SX, Sudharshan L, Macahilig C, Katyal M, Gao X. Exacerbation-related impairment of quality of life and work productivity in severe and very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:641–52.

Troosters T, Sciurba FC, Decramer M, Siafakas NM, Klioze SS, Sutradhar SC, Weisman IM, Yunis C. Tiotropium in patients with moderate COPD naive to maintenance therapy: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;20(24):14003.

Bolge SC, Joish VN, Balkrishnan R, Kannan H, Drake CL. Burden of Chronic sleep maintenance insomnia characterized by nighttime awakenings among anxiety and depression sufferers: results of a national survey. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(2):PCC.09m00824. doi:10.4088/PCC.09m00824gry.

Moline M, DiBonaventura MD, Shah D, Ben-Joseph R. Impact of middle-of-the-night awakenings on health status, activity impairment, and costs. Nat Sci Sleep. 2014;23(6):101–11.

Bolge SC, Doan JF, Kannan H, Baran RW. Association of insomnia with quality of life, work productivity, and activity impairment. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(4):415–22.

Bae SC, Gun SC, Mok CC, Khandker R, Nab HW, Koenig AS, Vlahos B, Pedersen R, Singh A. Improved health outcomes with Etanercept versus usual DMARD therapy in an Asian population with established rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14(1):13.

Bansback N, Zhang W, Walsh D, Kiely P, Williams R, Guh D, Anis A, Young A. Factors associated with absenteeism, presenteeism and activity impairment in patients in the first years of RA. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(2):375–84.

Braakman-Jansen LM, Taal E, Kuper IH, van de Laar MA. Productivity loss due to absenteeism and presenteeism by different instruments in patients with RA and subjects without RA. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(2):354–61.

Bushmakin AG, Cappelleri JC, Taylor-Stokes G, Sayers J, Sadosky A, Carroll D, Gosden T, Emery P. Relationship between patient-reported disease severity and other clinical outcomes in osteoarthritis: a European perspective. J Med Econ. 2011;14(4):381–9.

Chaparro Del Moral R, Rillo OL, Casalla L, Morón CB, Citera G, Cocco JA, Correa Mde L, Buschiazzo E, Tamborenea N, Mysler E, Tate G, Baños A, Herscovich N. Work productivity in rheumatoid arthritis: relationship with clinical and radiological features. Arthritis. 2012; 2012: 137635.

Di Bonaventura MD, Gupta S, McDonald MM, Sadosky A. Evaluating the health and economic impact of osteoarthritis pain in the workforce: results from the National Health and Wellness Survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12(1):83.

Dibonaventura MD, Gupta S, McDonald M, Sadosky A, Pettitt D, Silverman S. Impact of self-rated osteoarthritis severity in an employed population: cross-sectional analysis of data from the national health and wellness survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;15(10):30.

Hone D, Cheng A, Watson C, Huang B, Bitman B, Huang XY, Gandra SR. Impact of etanercept on work and activity impairment in employed moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis patients in the United States. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(10):1564–72.

Radner H, Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Remission in rheumatoid arthritis: benefit over low disease activity in patient reported outcomes and costs. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(1):R56.

Reilly MC, Gooch KL, Wong RL, Kupper H, van der Heijde D. Validity, reliability and responsiveness of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(4):812–9.

Tillett W, Shaddick G, Askari A, Cooper A, Creamer P, Clunie G, Helliwell PS, Kay L, Korendowych E, Lane S, Packham J, Shaban R, Williamson L, McHugh N. Factors influencing work disability in psoriatic arthritis: first results from a large UK multicentre study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(1):157–62.

Zhang W, Gignac MA, Beaton D, Tang K. Anis AH; Canadian Arthritis Network Work Productivity Group. Productivity loss due to presenteeism among patients with arthritis: estimates from 4 instruments. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(9):1805–14.

Pavelka K, Szekanecz Z, Damjanov N, Majdan M, Nasonov E, Mazurov V, Fabo T, Bananis E, Jones H, Szumski A, Tang B, Kotak S, Koenig AS, Vasilescu R. Induction of response with etanercept-methotrexate therapy in patients with moderately active rheumatoid arthritis in Central and Eastern Europe in the PRESERVE study. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1275–81.

Coyne KS, LoCasale RJ, Datto CJ, Sexton CC, Yeomans K, Tack J. Opioid-induced constipation in patients with chronic noncancer pain in the USA, Canada, Germany, and the UK: descriptive analysis of baseline patient-reported outcomes and retrospective chart review. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;23(6):269–81.

Fourquet J, Báez L, Figueroa M, Iriarte RI, Flores I. Quantification of the impact of endometriosis symptoms on health-related quality of life and work productivity. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(1):107–12.

Haglund E, Petersson IF, Bremander A, Bergman S. Predictors of presenteeism and activity impairment outside work in patients with spondyloarthritis. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25(2):288–95.

Kronborg C, Handberg G, Axelsen F. Health care costs, work productivity and activity impairment in non-malignant chronic pain patients. Eur J Health Econ. 2009;10(1):5–13.

Langley PC, Ruiz-Iban MA, Molina JT, De Andres J, Castellón JR. The prevalence, correlates and treatment of pain in Spain. J Med Econ. 2011;14(3):367–80.

Langley PC, Van Litsenburg C, Cappelleri JC, Carroll D. The burden associated with neuropathic pain in Western Europe. J Med Econ. 2013;16(1):85–95.

Takura T, Ushida T, Kanchiku T, Ebata N, Fujii K, DiBonaventura MD, Taguchi T. The societal burden of chronic pain in Japan: an internet survey. J Orthop Sci. 2015;20(4):750–60.

Vietri J, Otsubo T, Montgomery W, Tsuji T, Harada E. The incremental burden of pain in patients with depression: results of a Japanese survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;7(15):104.

Mann R, Bergstrom F, Schaefer C, et al. Characteristics of subjects with human immunodeficiency virus-related neuropathic pain in the United States: beat neuropathic pain observational study. Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 11th Annual ASRA Pain Medicine Meeting; Miami; 2013;38(1).

Asami Y, Goren A, Okumura Y. Work productivity loss with depression, diagnosed and undiagnosed, among workers in an Internet-based survey conducted in Japan. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57(1):105–10.

Beck A, Crain LA, Solberg LI, Unützer J, Maciosek MV, Whitebird RR, Rossom RC. The effect of depression treatment on work productivity. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(8):e294–301.

Giovannetti ER, Wolff JL, Frick KD, Boult C. Construct validity of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire across informal caregivers of chronically ill older patients. Value Health. 2009;12(6):1011–7.

Trivedi MH, Morris DW, Wisniewski SR, Lesser I, Nierenberg AA, Daly E, Kurian BT, Gaynes BN, Balasubramani GK, Rush AJ. Increase in work productivity of depressed individuals with improvement in depressive symptom severity. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(6):633–41.

Dibonaventura MD, Andrews LM, Yadao AM, Kahler KH. The effect of gout on health-related quality of life, work productivity, resource use and clinical outcomes among patients with hypertension. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12(6):821–9.

Khanna P, Nuki G, Bardin T, Tausche AK, Forsythe A, Goren A, Vietri JT, Khanna D. Tophi and frequent gout flares are associated with impairments to quality of life, productivity, and increased healthcare resource use: results from a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10(1):117.

Acknowledgments

Paul Miller and Harry Hill conducted the searches, data extraction and data syntheses and contributed to drafting the manuscript. Fredrik Andersson designed the project and contributed to drafting the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Paul Miller and Harry Hill received funding from Ferring Pharmaceuticals to undertake this work.

Conflict of interest

Paul Miller has received funding from Ferring Pharmaceuticals for conference travel. Fredrik Andersson is an employee of Ferring Pharmaceuticals, which markets treatments for nocturia.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miller, P.S.J., Hill, H. & Andersson, F.L. Nocturia Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Compared with Other Common Chronic Diseases. PharmacoEconomics 34, 1277–1297 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-016-0441-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-016-0441-9